#you can even argue it's in line with authorial intention to a certain extent

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I'm probably one of the few who finds the bits we got from Aegon as a character—while "inconsistent", disorganized and tonally a whirlwind—compelling, fascinating and worth inspecting and exploring (and maybe romanticizing and sexualizing :P). And this includes the textual sexual violence, and the heavily implied child sexual assault (whether pedophilic in nature or not aside for now). And though I understand people creating a fanon version expunging these sociopsychologically horrific, and fictionally hard to stomach aspects of his character, I can't say I even want to! I find him compelling because of these aspects, wanting the presentation of it may be for now.

His narrative, arc, symbolism and themes, and not to mention TGC's performance so far, are all just too compelling for me to pass on! Obviously biased, but frankly it's difficult to believe someone would read f&b and not realize the potential of his character and the entailing entertainment... On this note, I do have to say I find the complaints of certain fandom parts (they happen to be Aegon stans, and both team green and team black) about the choice to centre Alicent (both in the narrative and in Aegon's life) pretty disagreeable. It's wack, trite, and bitter. There are clear timeline oopsies and confusions due to the changes, and behind the complaints are genuine arguments to be made for an Update House of The Dragon that could have been, but the game ain't always fair... Just accept you are stanning a minor character, cast villain, stuffed like a pigeon with turkey filling, and eat your 10 minutes of beady eyed screentime. And just make everything about him? When someone takes a sip of wine, it's secretly about Aegon btw. All windows are about Aegon, when they are not about Alicent. Every dragonbond is secretly about Aegon/Sunfyre if you squint hard enough, George told me himself.

I think the major reasons why he comes off as deeply unlikable to the casual viewers (not even addressing the green/black tribalism for now) are due to unflattering framing and POVs that position him as either a gross nuisance, obstacle or clear antagonizing force. Some of this is due to needing certain characters covering certain aspects of a certain themes. How do the royals treat their servants? Good—bad is a big spectrum. Sexual violence is on it, and it happens to fall into Aegon's realm. And while considering the many other unflattering characteristics, u could argue this is overkill or unfair to Aegon, I gotta counter that's a deficient way of looking at fictional narratives. This character-lasered reading misses the forest for the trees. Not every character has to be likeable, relatable, or sympathetic from the get-go. And honestly, I think the many atrocities Aegon is collecting like Pokemon balls to be amusing and kinda compelling.

In another narrative, a character like Aegon's would b a byronic obsession in someone's romantic/gothic story, or a horror villain, or a god harassing poor mortal souls. There are very fun bits and pieces stuck in this guy and even in this age of many studios bucketing under fanbacklash, a guy can just hope the writers find him worthwhile enough a character. And rant into ur lovely inbox ofc.

And at the end of the day, people are just not gonna like a guy LOL. No amount of screentime or birthing scenes or dragonriding can make me find Rhaenyra compelling, and no lack thereof can make me find Alicent, Helaena, or Baela less compelling, speaking of female hotd characters only.

Okay almost.

Being they plan to introduce golden boy turned war criminal Daeron, I believe a both fun and horrific decision would be to make him compassionate towards Aegon's plights and woes and thus give the audience an entry into sympathizing with Aegon, which the writers clearly want us to do, all interviews and panels considered, cope and seethe as I have!

Are we even going to get a Daeron/Greenfam interaction? LOL What a deeply unserious show.

I would like to start off by thanking you for leaving such an interesting ask in my inbox! I think this conversation is a little overdue, since there’s been perhaps an emergence of the school of thought (lol) that suggests that greens upset or critiquing Aegon’s extra dark portrayal in the show are somehow whitewashing him or woobifying him. IMO that fundamentally showcases a divergence in people’s priorities in storytelling and how they interact with this fictional universe. I, myself, am very intrigued by dark!Aegon in fics and most of the works I enjoy tend to deal with taboo topics, so it’s a little unfair to paint everyone with the same dismissive brush.

However, I’m not just a HotD show watcher, I have been engaging with ASOIAF one way or another for over a decade now and I think I can mount a workable interpretation of how this series operates. One of the reasons I actually love it so much is because it has internal thematic logic and because, generally speaking, the characters that inhabit it are appropriately rewarded or sanctioned by the narrative (or at least it seems to be heading in this direction re: its endgame). Believe it or not, I was thinking of answering this ask by ranting about Ned Stark, but I decided not to, because we’d be here all day. 😅

Anyway, point is that I’m not very willing to sacrifice that aspect for the sake of character exploration that contradicts with the main themes and messages of the story. People are certainly free to disagree with me on this, of course.

I imagine it is a tricky business for authors, trying to decide exactly which and how much of a flavour of awful to assign to a character without ruining the rest of the story. Some might start with an outline or a feel for where they want the story to go, but, if you happen to create a character that veers off your intended path or seems to write itself in a direction you never planned for, it would be honest for you as a writer to acknowledge that and accommodate that accordingly in your story. Which isn’t truly a possibility here, as we need the characters to hit certain beats in the narrative and, ideally, they should do it in a believable way. This is often a problem I have found with Fire and Blood and lord knows I’ve already dissected it enough times here, if anyone cares to take a gander - the fact that characters are sometimes prevented to grow organically, because George needs them to perform certain actions in order to move the plot along. So, ideally, a good story would find a balance between these two scenarios.

So to me my main anti-argument is that the Dance was never a story just about Aegon, this is not the exploration of a fucked-up psycho rapist and why he does the things he does and how he thinks the things he thinks. While that certainly might be an interesting avenue, I am not super convinced the Dance of the Dragons could offer the appropriate space in which that kind of exploration could be pursued in a satisfying manner. This is an ensemble piece, and while Aegon is an important part of it, he also exists in relation to other characters. This exaggerated degradation of his would inevitably bring down his entire “side” with him and that, in turn, ultimately throws off the balance of the entire story.

Let’s stop for a minute and take a look at what they decided to go with in the show. Rhaenyra has consistently received the framing that her “mistakes” amount to (at most) victimless crimes (she is absolved from murdering Vaemond and the show makes no effort to explain the havoc caused by screwing up inheritance laws). Whereas what do we have for Aegon? 1. raping and terrorizing servants to the point of panic attacks; 2. enjoyer of the child-fighting sport; 3. implied sexual assault of children. This is beyond caricature. The addition that he enjoys watching his own children fight and that they file down their teeth to make them more formidable, stuff that wasn’t even in the books, is just downright infuriating.

These are not traits you endow a character with because you’re interested in exploring the deep dark depths of human depravity. That task was always impossible in the first place with a character who has so little screen time anyway and I would argue it was never really a priority anyway. The intention was always to make Rhaenyra look good by comparison and that’s not something I can respect from a storytelling perspective.

Note that this is the starting point for Aegon and Rhaenyra. This is supposed to show how they behave before the war, in a relatively stress-free situation, when they’re unburdened by war trauma and their family dying - explanations that could be given as reasons for their later ruthlessness. But nothing show!Rhaenyra (or even book!Rhaenyra) has ever done could ever hope to amount to the trifecta of awfulness that they assigned to show!Aegon.

So, what exactly are we doing here? The point of Aegon and Rhaenyra as direct adversaries was always that they inhabit a similar plane. It’s not even about Aegon being likable or sympathetic, it’s about the fact that it separates him too much from Rhaenyra and it positively sanctifies Rhaenyra by comparison. You could certainly prefer one over the other, but their differences are meant to inspire conversation; they cannot be so completely removed from one another as to operate in different leagues of morality. If we monsterize Aegon too much, we don’t even have the space to properly explore that in the story and it would mess too much with the way his character needs to evolve in order to hit the particular narrative beats that George decided are set in stone. So giving him these massive transgressions as a starting point and turning him basically into the Antichrist throws the rest of his arc off balance for me and the thematic parallels become too off-kilter for me to be able to enjoy it.

To me Rhaenyra’s story is very reminiscent of (white) feminism, very “rights for me but not for thee”: a rich, white, privileged woman fighting for her own advancement and not caring about the plight of anyone else. The Dance of the Dragons is meant to inspire conversation and debate, both on the legal front and on the political utilitarian front. Is male primogeniture fair, even if it maintains stability in the realm? Can we change that? How? Does shifting to simple primogeniture when it comes to royal succession engender progress in some way? Should royal succession reflect inheritance laws for the rest of the population? How are laws changed in a medieval common law system? Is it fair for the King to change laws however he wants, at the drop of the hat, or should the lords have some say? What can/should the King do if his vassals refuse to abide by his choices? When it comes to waging a destructive war to replace one “unworthy” candidate for the throne with another “unworthy” candidate, where do we place that on the moral spectrum? Is the population thriving/not dying in war more or less important than maintaining male primogeniture? Is it really worth it just to have a nominal female successor that won’t really bring about systemic change? These questions are really worth exploring and there are no straightforward answers to them, but if Aegon is Satan on Earth, none of these questions matter anymore, because Rhaenyra automatically becomes the better option and no price is steep enough to pay to get rid of Aegon. And the point never was that Rhaenyra would make a better ruler than Aegon or is even a better person than Aegon; trying to shoehorn her into that narrative only hurts the story overall.

There’s something to be said for the fact that in the last stages of the war, Aegon’s and Rhaenyra’s journeys inversely parallel each other: while Rhaenyra is rejected by the population and kicked out of King’s Landing while she’s occupying the Iron Throne, Aegon manages to convince people on Dragonstone to fight for him and he takes the castle with little resistance. There is something to be said for the fact that it’s Aegon who gets to kill Rhaenyra, not the other way around. That he’s the one who gets to live that little while longer. The author could have simply chosen for them to have one last battle and end up killing each other, but he doesn’t. And IMO we would not be able to get to that point in the story in a way that feels true and organic to the internal logic of this fictional universe if we corrupt Aegon’s development and make him so reprehensible to begin with.

TLDR: I take issue with HotD’s portrayal of Aegon in direct comparison with the text of Fire and Blood, but I am open to dark!Aegon explorations in fic. However, I do not feel like this is appropriate in canon, as it messes too much with the balance of the story and corrupts the wider themes and messages, both of the Dance of the Dragons and of the ASOIAF series in general.

#i also like the fact that they centered the story on rhaenyra and alicent#you can even argue it's in line with authorial intention to a certain extent#the princess AND the queen#however aegon and rhaenyra are also the leaders of their respective factions#and whatever they do/are reflects on their entire camp#as figureheads of the civil war they should not be operating on differing planes of morality#ask#anon#aegon ii targaryen#hotd critical [aegon]#hotd critical [rhaenyra]#hotd critical [storytelling]

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hymnstoke Intermission

Andrew Hussie had the courtesy to drop some thoughts on the Epilogues, the full text of which can be found here. As you can probably tell, it’s dense, so I’ll summarize what I consider the key points.

1. Hussie intended the Epilogues to be “conceptually distinct” from the main narrative of Homestuck (i.e., Acts 1 through 7).

2. Hussie intended the Epilogues to set new narrative stakes and establish a way for the narrative to continue (as opposed to the traditional idea of an “Epilogue” as something that resolves what came before).

3. By labeling the Epilogues as “Epilogues” while not adhering to traditional expectations of what an epilogue entails, Hussie intended to prompt readers to question storytelling concepts and the agenda of the storyteller.

4. Hussie intended to cede his authorial control over the Homestuck story and “pass the torch” to the fandom.

5. Hussie intended to prompt the fandom to develop skills like “critical discussion, dealing constructively with negative feelings resulting from the media they consume, interacting with each other in more meaningful ways, and trying to understand different points of view outside of the factions within fandom that can become very hardened over time.”

I actually disagree with several of Hussie’s conclusions, which probably sounds hilariously presumptuous. But if Hussie truly wants the fandom to develop skills in critical discussion, and to foster and understand different viewpoints, while also ceding his authorial control over the work, then his word being “Word of God” has to be called into question. Act 6 of Homestuck already does this; Hussie’s author avatar is literally killed followed by a flash titled DOTA. DOTA, of course, being short for “Death of the Author,” a frequently-cited essay by Roland Barthes that argues that author's intentions can neither be wholly known nor taken as the sole interpretation of a work.

It’s arguable whether Hussie’s shout out to this essay is meant to be an endorsement of its thesis, and I think a claim could be made that the DOTA in Homestuck is inherently parodic; Hussie’s author avatar continues to exist and influence the story even after his “death,” and at times (such as the Meenah walkarounds) the author avatar appears to give direct statements of the author’s intentions behind certain creative decisions. In fact, the DOTA flash itself marks one of the Hussie avatar’s most direct interactions with the story, as it is during this flash that he gives Vriska the Ring of Life.

Even now, Hussie’s actions contradict his claims, at least to some extent; he cedes narrative control and promotes differing critical interpretations at the same time he dumps a tremendous block of text explaining the intentions and goals of his work. An author’s statement on “what the story means” usually affirms his or her control and quashes differing viewpoints, after all. But it’s not something new. Homestuck has always blurred the line behind author and fan. Some of Hussie’s statements I don’t take as major revelations but rather reiterations of themes that have been clear since Act 1.

If you have read my more recent Hymnstoke posts, you can probably guess which of Hussie’s points I disagree with. In particular, I think the Epilogues are too thematically important to Homestuck to be treated with the kind of “take it or leave it”/“canon or non-canon” ambivalence Hussie claims in his post. Or maybe it’s more that I wish it didn’t have that kind of ambivalence? Because his logic is sound; the Epilogues are presented in a way that sets them apart from “Homestuck Proper.” The AO3 fan fiction cover page, the prose, the way they’re organized as a distinct entity on the website, all of these elements contribute to and support Hussie’s claim of separation. Perhaps, then, my counterargument is that the Epilogues shouldn’t have been displayed this way; that they should have been a fundamental part of the story, one that is unquestionably considered “canon.”

Without the Epilogues, the ending of Homestuck is bad. Really bad. Game of Thrones bad. The original ending of Homestuck fails Homestuck on every conceivable level. It’s a poor resolution of the plot, as it relies on a deus ex machina (Alt!Calliope) while leaving tons of smaller narrative elements completely unresolved. It’s a poor resolution of the characters, as most of them wind up being irrelevant (even those given absurd amounts of screen time, like Jake) and their personal issues are resolved off-screen during a timeskip. It’s a poor resolution of the themes, as despite constant statements that one can’t cheat their way to “development,” that is exactly what happens when Vriska is revived and fixes everyone’s problems instantly. It’s a poor resolution of the structure or form, as what was a tightly-wound machine narrative that relied on innumerable tiny parts sliding into perfect order ended with a big dumb fight scene where people just whap each other over and over until the good guys whap hard enough to win. Beyond the fact that the ending is “happy,” I still can’t find much good to say about it even after years of turning it over in my head.

And during the hiatus-strewn period that marked Homestuck’s end, Hussie was noticeably scant on dropping essays about his intentions.

The Epilogues redeem so much of what went wrong with the ending of Homestuck. I won’t delve into the specifics in this post, as I should probably save it for a more comprehensive series of posts about the Epilogues. But from that perspective, it feels to me as though the Epilogues should not be divorced from Homestuck so thoroughly.

But see, my disagreement with Hussie on this point is a bit disingenuous for another reason. Because, like his claims of ceding authorial control, he’s contradictory here too. Consider these points:

1. Hussie intended the Epilogues to be the launching point of future story developments.

2. Hussie, ceding his own control, intended these future developments to be created by the fans.

3. Hussie designed the Epilogues so that the fans could accept or deny them outright, consider them “canon” or “non-canon.”

If the Epilogues are the breeding ground for Homestuck’s future, then that part of the fandom that denies them renders themselves inert. Without the Epilogues, Homestuck is over. It’s done. The window of our Pynchonian party is closed. All life has petered out; no energy enters to sustain it. The Epilogues open the window. Denying the Epilogues kills the story, and thus the fandom; accepting them leaves room open for the future. And if the part of the fandom that rejects the Epilogues withers and dies, that means only the fandom that accepts them will remain. Ultimately, the Epilogues will be considered canon by the Homestuck fandom, because those who disagree will no longer be part of the fandom, at least the active one.

That probably sounds imperious. But it’s not something I want; the people who deny the Epilogues ought to have a voice as well, and nobody is stopping them from providing their opinions. But I have a hard time imagining that people who deny the Epilogues will stick around in a fandom for a work now defined by the Epilogues. As such, many of Hussie’s conciliatory claims fall flat or seem overly idealistic. Can the fandom continue as a divided house on such a fundamental line when future developments to the Homestuck story will be based on the Epilogues? The canonical arguments for which books belonged in the Bible did not end in blithe harmony; one viewpoint prevailed and all schismatics extinguished. Obviously there will be no burnings at the stake over Homestuck canon, but in a world where there are so many options for entertainment, those who do not accept Homestuck’s active element will probably leave of their own volition.

There's also a third option, expressed by one of the commentators on the Reddit thread I link at the beginning of this post.

Here's my suggestion for you, Hussman. Big subversion, you'll like it: Make "Homestuck 2" and then not have anything form [sic] Homestuck in it at all and just make the story you actually want to make.

The Homestuck fandom might die, but the “Hussie” fandom will survive, as long as Hussie himself continues to create art. Before the Epilogues, I often expressed a similar sentiment. I wanted Hussie to get away from Homestuck, make something new, even if it was just something short and far less ambitious than Homestuck. I think Hussie is a strong storyteller and writer in his own right, and he did not merely “get lucky” with Homestuck the way a hack gets lucky when their trashily-written novel strikes a perfect chord with the culture and sells millions. If Hussie does actually intend to cede authorial control and leave Homestuck to the fandom, then what is his next move? Retirement at 40? I hope not.

Those were my hastily-written thoughts on Hussie’s commentary. While at times contradictory, I consider Hussie’s claims and actions in line with themes established throughout Homestuck. But I also question whether his storytelling decisions will be able to achieve the result he desires for the fandom.

Whether he or we can achieve it, I do agree with Hussie’s hope to create a fandom that is smarter, more willing to view the work with a critical lens, to discuss with one another, to understand each other’s viewpoints, to deal with difficult subject matter. I think a lot of people can be scared to delve deeply into a work, either because they only want their entertainment to be light escapism or because they feel gatekept by not knowing a lot about literary criticism as a field of study. Maybe escapism is fine, but it’s not the only use of art. Treat the stories you like as art and really ask yourself what you like about them, what makes them good, and especially what it means that those things make it good. Those questions will serve a fitting substitute for an understanding of postmodern literary trends of the 20th century.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

magpiescholar replied to your post: just got into a conversation that reminded me how...

I missed this and I would love to read a rant from you about it!

oh boy oh BOY YOU WANT A RANT YOU GOT A RANT

okay so like. I get why 2012-ish Salmon Rioters were very easily sucked in to the whole “only HoME is canon, the published Silmarillion can get rekt/only MY SPECIFIC INTERPRETATION of HoME is canon everybody who doesn’t agree with me can go sit on a tack” thing? There was a lot of eloquent, compelling, well-researched meta that waxed poetic on why (for example) the Valar were actually malevolent rather than merely completely out of touch with the needs of the elves in their care, and it did a good job of sounding authoritative and it inspired a lot of fans. And I think it caused a lot of people to fall in love with versions of specific characters that arose as a result of what can honestly in some cases be called revisionist meta, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing?

but the thing that bothered me then and bothers me now is 1. the insistence that only some types of choose-your-own-adventure canon based on loose or highly specific interpretations of certain lines from fan-preferred texts were Okay or Right or deserving of fan interest 2. the exclusion of other texts from HoME as authoritative 3. the complete ignoring of the published Silmarillion as a valid interpretation of the source material SO let’s tackle these in order

point 1 mostly came up with the discussion of the Shibboleth of Fëanor iirc, which I recall was cited as the Most Accurate Version Of Events due to a lot of factors but its status as a later writing and addition to the Middle-Earth sandbox world seemed to lend it legitimacy. I remember getting into arguments with a couple of people because I found the presentation of Fingolfin’s actions to be wildly out of character when compared to everything else he ever did in the collected HoME, and therefore I came up with a few “choose your own adventure” style loose interpretations of the Shibboleth to justify why this particular record made him look bad; the general response was eloquent enough but came down to the fact that a lot of the people I was talking to preferred this Fingolfin because it made Fëanor (who was even more of a fan favorite back then) look better - of course, when I read the Shibboleth for the first time Fëanor reminded me of one of those “goes to city council meeting with giant folder about UFO attacks, rants for ten minutes” people, because while I completely understood feeling hurt about a dialectical shift changing the pronunciation of a name I couldn’t grasp why a dedicated linguist/language nerd was so insistent that this was a continent-wide conspiracy? bro. languages change. it’s necessary for survival of your tongue.

point 2 was mostly a corollary to point 1, because if only the fan-preferred HoME essay/narrative/whatever was Good, anything that contradicted it was Bad. And there were a lot of reasons for this, but it annoyed me because if you went against the Tumblr consensus you got yelled at, no matter how thoughtful or detailed or well-researched your academic work was - it didn’t matter even if you were able to make definitive statements about authorial intent based on a knowledge of Tolkien’s personal life/theology/etc, because it didn’t match up with the Approved Version Of History, which was generally “the Fëanorians did nothing wrong” (and like. I love the Fëanorians? But keep in mind that I also love Anakin Skywalker. I feel like that era of fandom had a hard time remembering that characters can be terrible people but awesome storytelling devices, but that’s just my opinion.) to the extent of arguing with people who had real-life trauma in their past similar to things suffered by Kinslaying survivors (I’m not naming names but I remember that series of posts and it was cringeworthy) that their opinions weren’t okay because My Precious Babies Did Nothing Wrong

and maybe I’m generalizing? I know that I love the Fëanorians and I think they’re all delightful murderous unstable elves and great characters - hell, my phone case is the Star of their House and ‘Tenn’ ambar-metta!’ in Quenyan Tengwar - but I also know that I saw a lot of opposition to the idea that they’d made mistakes. (And I get that? Part of why I made that “Fëanorians are millennials!” post from ages ago was an effort to explain why I thought our generation of fans were so quick to defend them and why opinions had shifted so drastically)

anyway on to Point 3, which is that I saw an attitude of “if you’ve only read the Silmarillion you can’t call yourself a real fan” paired with “the Silmarillion isn’t an authoritative or truly canonical text”. And again, there are legitimate arguments to be made about that? because yeah, I don’t like Chris’s editing either, I think sometimes it sucks. But I don’t think that we can discount the fact that this is the version that the guy charged with preserving the creator’s legacy declared the closest to the intended product, and I don’t think it was fair to expect all fans to slog through twelve volumes of history lectures/linguistic essays/sociological studies/poetry/Chris’s commentary about everything just so they could engage in discussion of meta. It felt very insular and in-crowd, and while I will admit I liked that at the time now I kind of feel it was... harsh, and intimidating.

anyway. that’s my rant.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Thoughts Jean’s Character Development (Prompted by the HS AU).

CW: Bullying and the molestation scene.

So, in keeping with the rhetorical principle of kairos (timeliness of an argument), I think the time is ripe for a (re?)consideration of Jean Kirstein’s presentation in the Attack on Titan manga. I noticed that a bit of a discussion about Jean’s character popped up in the wake of the High School AU fake preview for volume 22 (one which I’ve already participated in a few times) and since we’ve just had a massive time-skip in the series to kick off the final arc, I feel like we can examine the development of the characters from the fall of Wall Maria to their journey to the ocean as discreet units. In fact, it may be useful to look at where some of them have ended up and how they got there before launching off into the new arc, so if you like what I have to say about Jean please send me suggestions for more character analysis like this!

The reasons I want to talk about Jean are twofold. The first is obviously personal interest. I’m discussing Jean regardless of whether or not anyone else really wants to read it because I find his portrayal and development intriguing xD. But my jumping off point is a little bit more specific, to come back to the question of kairos. The High School AU, however silly or tongue-in-cheek, has raised questions in fandom about whether or not Jean is a bully in canon or would be one in an AU that I would like to address.

Although I’m taking an AU’s depiction of Jean as the starting point of my inquiry, this post is pretty much only concerned with the canon material of the manga (not the anime: I have already discussed discrepancies between the manga and the anime’s portrayals of Jean here). Even though Isayama drew the High School AU and therefore it probably has value as meta, I feel strongly that the Jean depicted therein has little in common with Jean in the manga. I’ve been attempting to follow up on an interview which was mentioned to me, where Isayama supposedly said that in any other universe Jean would be one of Armin’s bullies (I’d appreciate any help in locating it! So far I’ve only been able to find other people mentioning it in their posts but no source). I find this kind of blanket statement on Isayama’s part a little bit more troubling—how did he come to understand his character this way? I guess it doesn’t matter to a certain extent, because authorial intent or understanding is by no means the end-all be-all of interpretation—and therefore I would like to further explore the question of Jean’s canonical presentation to attempt to answer the question: is Jean Kirstein ever, at any point, a bully?

My answer, as you may be able to guess from the fact that my blog is Jean themed, is a pretty hard no. In fact, within canon I would argue that Jean is one of the more empathetic and morally astute characters, and that the development he undergoes is less of a complete ethical realignment and more of an adjustment of his goals and strategies. He doesn’t begin cruel and transform into a kinder person; he starts off as astute but self-centered and his development revolves around using his skills to protect and champion others rather than just himself.

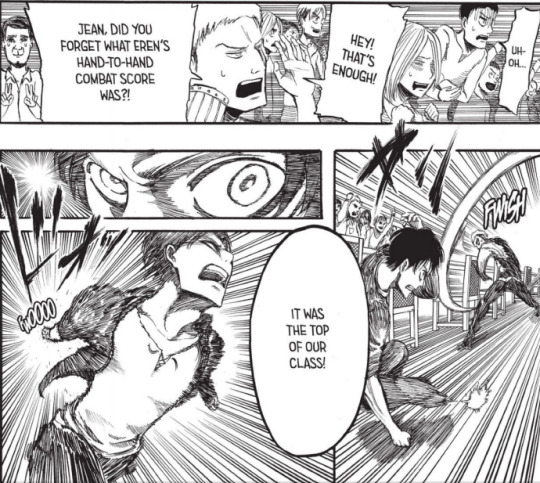

I would say Jean actually starts off as a bit of an outsider among the 104th (a facet of his personality that the original draft of the HS AU actually preserves) and that Eren generally has more clout than him; in fact, trainee Eren would probably not be a compelling target for a bully, all things considered. Jean’s fights with him don’t seem to come from a place of maintaining dominance over someone weaker and instead take the form of pretty mutual brawling. Indeed, he may be at a bit of a disadvantage when fighting against Eren physically, as demonstrated in this scene.

Chapter 3. Jean is “punching up” here, as it were. After a battle of words, Eren and Jean hit each other simultaneously and initiate a fight in which, according to Reiner, the odds may be slightly against Jean. Mikasa also implies Eren picked this fight after she intervenes. Also I just noticed that dude giving peace signs in the far left corner lol.

All in all, Jean is never depicted as picking on someone weaker than himself to establish dominance at pretty much any point in the series, as far as I can remember (in fact, he’s the only one to stand up to bullying in some situations, as will be discussed below). Isayama shows Jean hassling Marco, teasing Sasha, and picking fights with Eren (the first of whom has some pretty naive worldviews and the latter of whom give as good as they get and even start said fights). Jean’s so irritating to Eren--at least in the manga, I know they nerf him considerably in the anime--because he’s astute and quite often actually has a point. He’s not, unlike Armin’s bullies in the series, calling Eren a heretic for even thinking of going outside; rather, he seems concerned that Eren is going to drag other people outside to killed along with him (particularly Mikasa, initially). He can be rude and he has a short fuse but he’s not seeking people out to hurt them and enjoying it. He has a sore spot about Eren, but that’s really more of a fight between equals--they make each other mutually uncomfortable because Jean reminds Eren of the stakes involved in achieveing his goals and Eren provokes action from Jean.

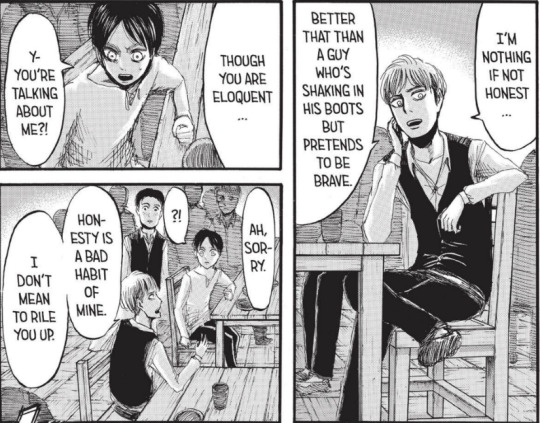

In fact, I’d say Jean’s commitment to the truth aligns him a lot more with Armin than his bullies or even with the other members of the 104th. For instance, as this post points out, they both get themselves into trouble by speaking their minds as kids.

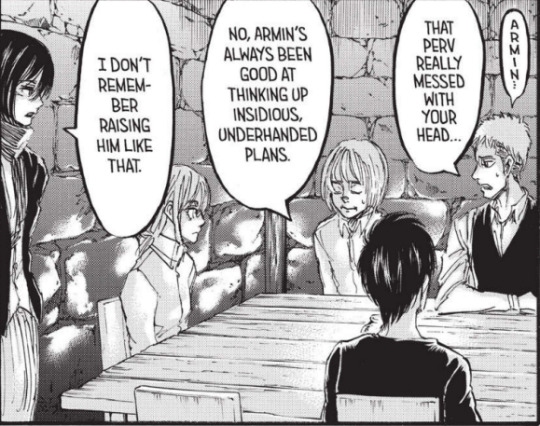

Armin in chapter 1 and Jean in chapter 16. I still can’t get over Jean calling Eren “eloquent”; regardless of Eren’s good intentions, I think Jean is very right in pointing out how Eren’s rhetoric doesn’t sound all that different from the story the higher ups told about the cull. But I also find it super interesting that there is no bad intent in Jean’s speech here; given the “truce” they call afterwards, I think he’s serious that he doesn’t mean to attack Eren. In the anime Jean doesn’t get this line about eloquence in and the scene is much more hostile.

Which brings me to my point about his development. The way I read it in the manga, Jean’s journey is not about transforming from a cruel person into a kinder one (since he is never depicted as cruel in the first place), but from a self-centered individual into a responsible one: specifically, a person tasked with championing the weak. Jean has always seen the problems with the government--he talks about the cull of twenty-percent of the population as a suicide mission, he pokes fun at the rhetoric of calling the people who are forced to settled in outskirt towns “heroes”--but instead of attempting to do anything about it his initial impulse is to play the system so that he survives as long as possible.

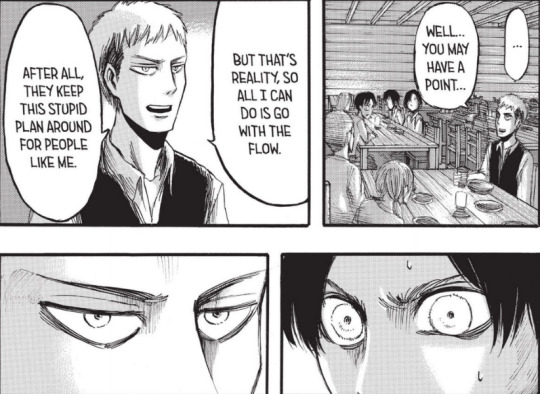

Chapter 17. They stand up to start fighting simultaneously immediately after this. Eren is sweating here, implying nervousness, and his eye is twitching; Jean’s pretty calm now, but in just a few panels his jealousy over Eren’s friends will get him into trouble.

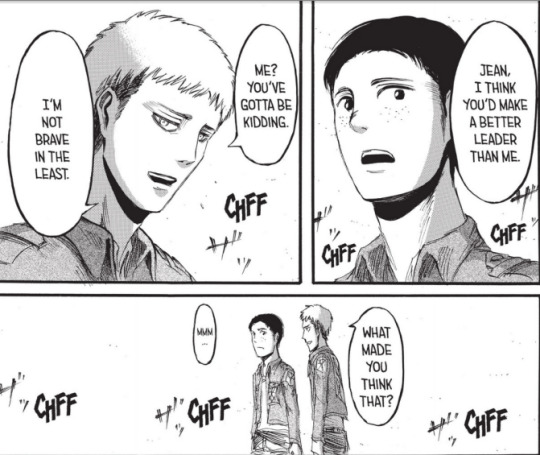

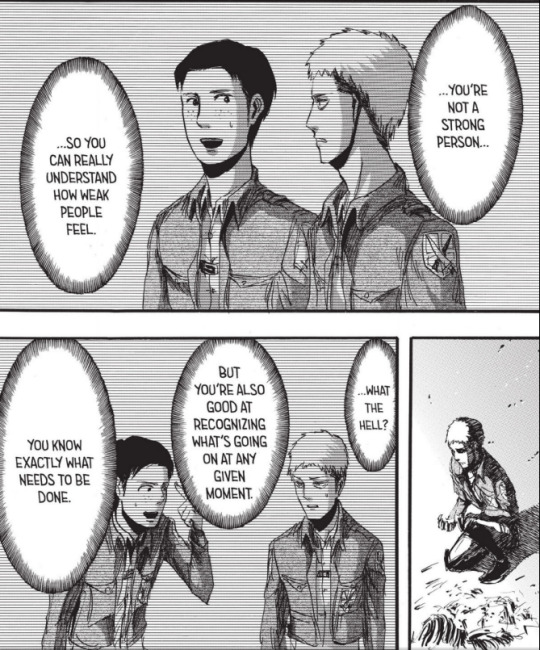

In fact, Marco thinks Jean’s pragmatism and desire of self-preservation put him in a unique position to stand up for the weak--the opposite of picking on them.

Chapter 18. This memory comes to Jean when he’s trying to decide how best to protect his comrades from further death and devastation.

Marco’s point is that Jean has a unique combination of skills and personality traits which he can utilize to protect the weak, both from the titans and (eventually) other humans who are seeking to oppress them. Jean’s “weakness” leads him to value life, so he’s not going to take certain risks unless he has to--and he’ll be honest it about it with his soldiers, so they’ll know he has their interests at heart. He only makes sacrifices reluctantly, when he must in order to preserve a larger number of people (as seen in Trost). He’s also astute: he’s suspicious of empty rhetoric (like the government deals in--it’s so weird that Marco is the one implying some of this, given his fondness for the king; perhaps it’s just that the society views these attributes as weak, given how messed up it is) and he can take in any situation pretty quickly. He’s aware of the systems of oppression that govern the Walled World (culls and bait towns), and his development seems to center on widening the scope of how he resists those systems rather than his awakening to their existence: he needs to look out not just for himself, but others or else he is complicit in their suffering. So he joins the Survey Corps, not because he sees Eren’s vision of “freedom, no matter how high the costs” but because he wants to protect his friends.

Chapter 18. I don’t think bullies worry so much about others. There’s a sense of camaraderie that seems to include Jean expressed at other points in the manga--like, yeah he’s a bit rude sometimes, but he’s our rude guy and we like him that way. No one seems to have a serious problem with him.

This seems to be how others understand Jean’s change of heart as well. Everyone is weirded out by how “responsible” he is now, rather than how much kinder--implying they didn’t really see him as cruel in the first place. No one comments, for instance, on Jean personally supporting Connie or Armin after some of their difficulties, but they do notice when he speaks up for helping others more generally, particularly at great risk to himself.

Reiner in volume 6, when Jean suggests buying time for the platoon to retreat after the Female Titan devastated their forces.

Connie, Eren, and Armin commenting on how Jean’s changed in volume 13. I’m not quite sure about Armin’s comment here; was Jean ever really a “bad guy” or just a bit of an asshole sometimes in the course of disagreeing with Eren?

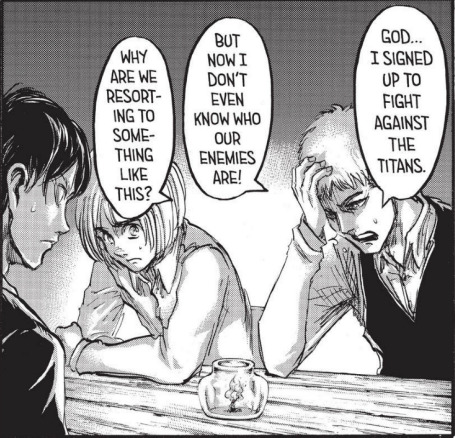

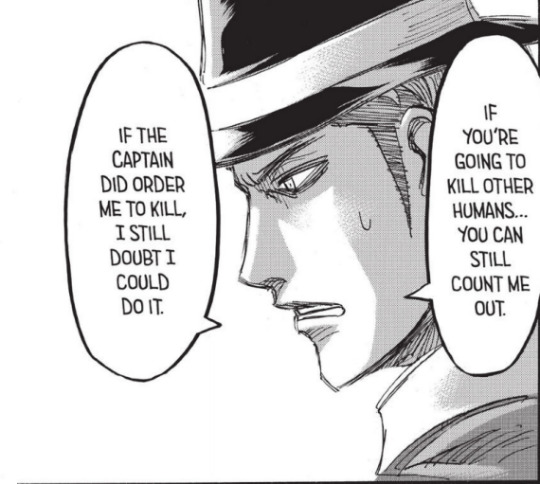

And I think Jean takes his newfound commitment to others seriously, which leads to some of his struggles during the Uprising arc as he tries to distinguish the most ethical course of action when the metric of “human versus titan” fails. He always attempts to voice his objections within the parameters allowed to him by the military, although not always in the most productive ways (think about that joke about stabbing incompetent commanders in the back . . .). In fact, he’s even willing to challenge the SC when he thinks they’re going too far in the name of the coup: part way through my initial read through of the series, I started looking to Jean for commentary on the morals of a coup that stems from within the military rather than from the will of populace.

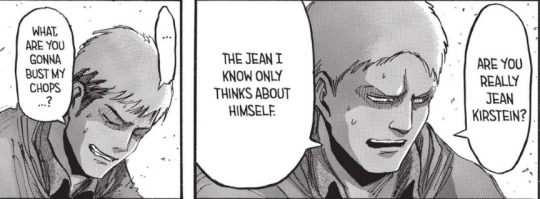

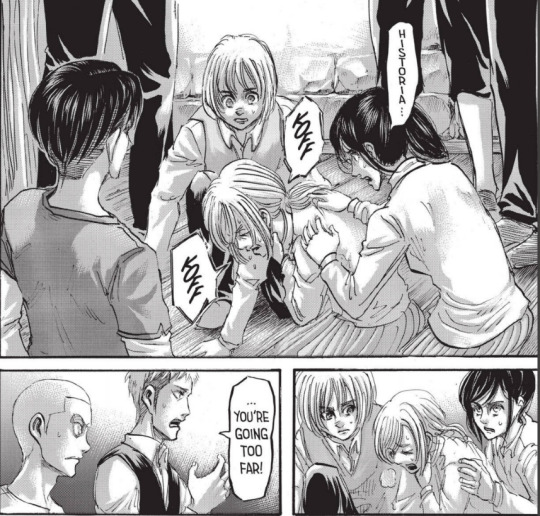

Jean voices his objections to torture, volume 14. Surely someone with a cruel streak or the impulse to bully would be able to think of some justification for torture.

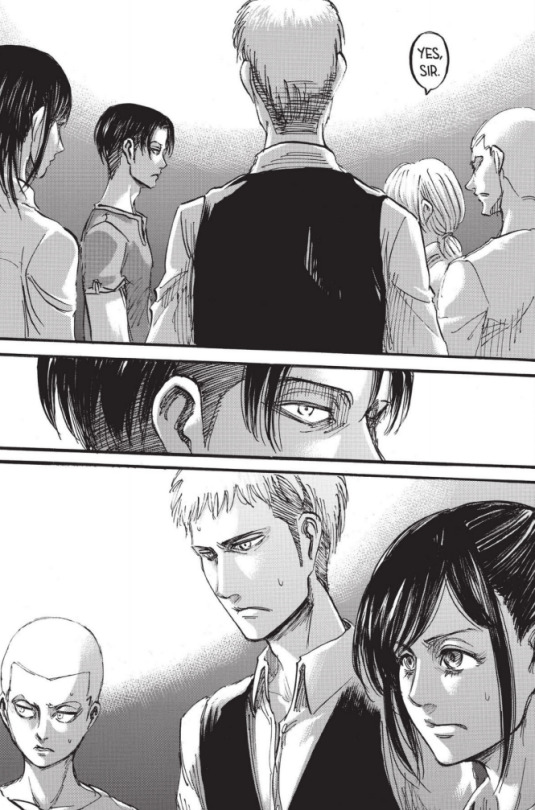

Everyone is upset over Levi’s treatment of Historia, but Jean’s the only person who actually says anything, volume 14.

Jean is the first and last person to raise objections about the coup’s methods in this scene, volume 14. He feels so strongly about it he considers defying orders.

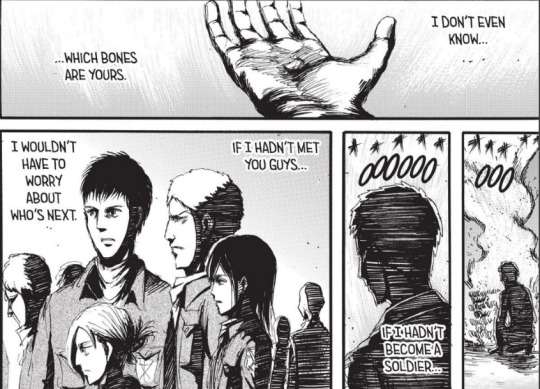

And I don’t necessarily want to get too much into the molestation scene from chapters 52 and 53, but Jean seems to object to being asked to participate in the “bait” scheme, because it makes him somewhat complicit in what happens to Armin. While presumably other members of the 104th comforted Armin after his trauma, we only see Jean doing it. In fact, he’s the only one who speaks about it apart from Mikasa, who alludes to the molestation once on the rooftop while she and Levi are setting up the trap.

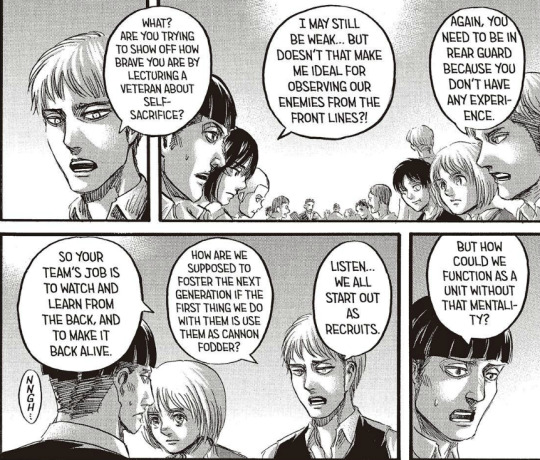

Jean struggles with the tenants of the mission, which is to act as bait until they can spring a trap for the big boss of the Reeves’ company, volume 13. The implication seems to be if he were not compelled to be “Eren” at this point he could do something about what is happening to Armin.

From volume 13. Unfortunately, it also seems like Connie and Sasha are laughing here. :(

Of course, even at this stage of his maturation there’s still room for Jean to grow. For example, Jean’s response to Armin’s second “gesumin” moment, wherein he suggests fooling the masses in order to get them on the survey corps side, is to blame Armin’s unethical proposal on his recent trauma.

Volume 14.

This is not Jean’s finest moment, but I read it as him (however problematically) trying to make sense of Armin’s suggestion; a suggestion which involves manipulation and lying, two things antithetical to Jean’s own values. This ableism doesn’t belong just to Jean, but is pervasive throughout the world of Attack on Titan (many people toss around insults related to intelligence and mental health), so I read this also as a bit of a knock to their society; they could all do better. This is not to excuse Jean here, but to just acknowledge the systematic nature of the problem.

Overall, however, Jean’s the only person who’s attempting to help Armin (that we see, obviously) and I think these scenes are where we get a fuller sense of his empathy; an empathy that also leads him to try to help Eren (again, in his own blunt and awkward way) after the events of the Reiss chapel. It’s the same empathy, I think, that Marco alludes to when he says Jean understands the weak and should endeavor to help them. We can read that empathy back into his concern for his fellow soldiers, who are constantly asked to risk their lives for causes that may not even have their best interests at heart. Whereas Armin’s analytic nature leads him to discover people’s secrets and predict their movements, Jean’s empathy grants him perspective on their feelings--he can see the human in pretty much anybody, which I view as his main strength.

Over the course of the coup, Jean becomes the main voice of dissent. Although Sasha and Connie often nod along with him, he’s usually the one who either speaks first or speaks at all, and Levi realizes that he’s going to have to convince Jean eventually if he’s going to maintain order in his ranks.

From volume 14. I think it’s so interesting that we’re looking first at Jean from behind and then at him through Levi’s eyes. It’s almost like we’re meant to be identifying primarily with Jean and Levi’s looking at us--Levi has to convince us he’s right, in addition to convincing Jean. He’s also centered here, suggesting his leader status among the other recruits.

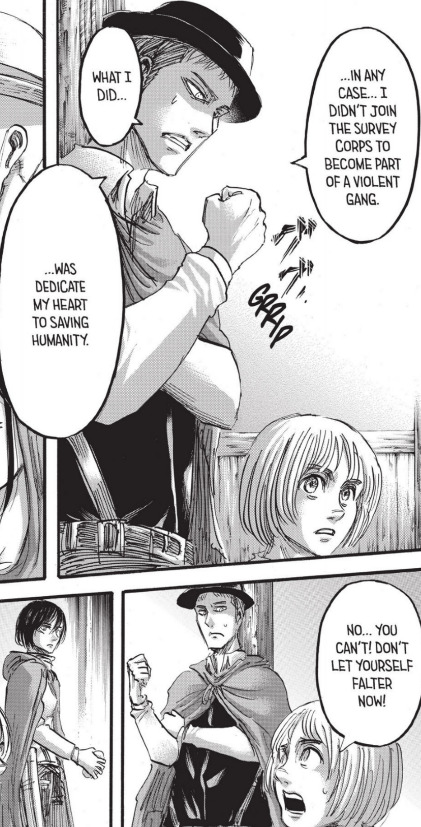

Jean’s biggest development during the coup stems from struggling with the idea that there’s no way to be ethically pure. He joined the Survey Corps in order to help others after Trost made him fully aware of the stakes but sometimes that’s a murkier process than it initially seems. Jean decides after Armin kills someone for him (sacrificing his own innocence for Jean’s life), that the best he can do in his current situation is to protect his comrades. And he takes that mentality with him after the coup, as demonstrated in this scene where he lectures Marlowe.

Chapter 72. Jean’s trying to tell Marlowe not to get swept up in the rhetoric of self-sacrifice.

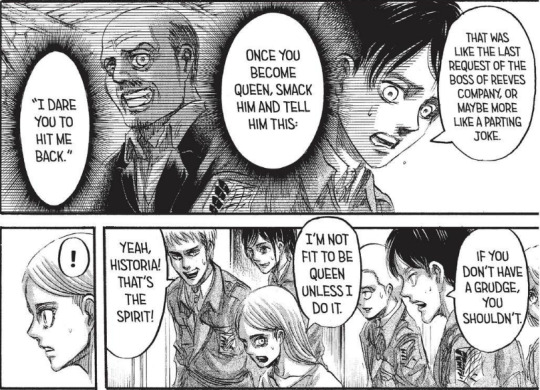

Yet I like that Jean doesn’t come out his experience completely cowed by Levi (who, admittedly, does not want Jean to be cowed or even want Jean to think he’s always right, based on their discussions), as we can see in this scene where he encourages Historia to keep her promise to Boss Reeves and punch Levi in revenge for his violence towards her.

Chapter 70. Eren thinks she should let it go but Jean cheers her on.

So, in summation, Isayama can reinterpret Jean as a bully if he wants to in his AUs for comedy, but I think that’s an oversimplified and even quite inaccurate reading if we want to take it seriously, even of pre-development Jean xD. Jean starts off as an observant but self-centered person who doesn’t intimidate the weak but doesn’t champion them either; he just wants to survive. But Marco’s death makes him realize the full extent of the care he feels for his comrades and he sets out to protect them and support them, even in defiance of his commanders. He questions the rhetorical maneuvering of the powerful and seeks to live honestly. None of that sounds like a bully and certainly none of that sounds like it would develop into a bully in a different world where there were no titans or no totalitarian government. And those are my two cents xD

#jean kirstein#snk meta#snk analysis#snk character analysis#hs au#maybe I overthink things sometimes but I just have to say them xD

97 notes

·

View notes