#xenacanthida

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A group of tiny fossilized chondrichthyan teeth of Barbclabornia luedersensis from the Wellington Formation in Waurika, Jefferson County, Oklahoma, United States. The lack of a central cusp distinguishes this species from the contemporary xenacanthid, Orthacanthus. While its teeth are tiny compared to contemporaries like Orthacanthus, Barbclarbornia is believed to be the largest member of this clade, potentially growing up to 5 meters long. Despite shark-like appearances, xenacanths like Barbclabornia are not true sharks.

#fish#shark#chondrichthyan#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#barbclabornia#xenacanthida#permian#paleozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#バーブラボルニア#ゼナカントゥス目#サメ#化石#古生物学

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xenacanthus

By @stolpergeist

Etymology: Weird spine

First Described By: Beyrich, 1848

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota, Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii, Euselachii, Selachimorpha, Xenacanthida, Xenacanthidae

Referred Species: X. atriossis, X. comrpessus, X. decheni, X. denticulatus, X. erectus, X. gibbosus, X. gracilis, X. howsei, X. indicus, X. laevissimus, X. latus, X. ludernensis, X. moorei, X. ossiani, X. ovalis, X. parallelus, X. parvidens, X. ragonhai, X. robustus, X. serratus, X. slaughteri, X. taylori

Status: Extinct

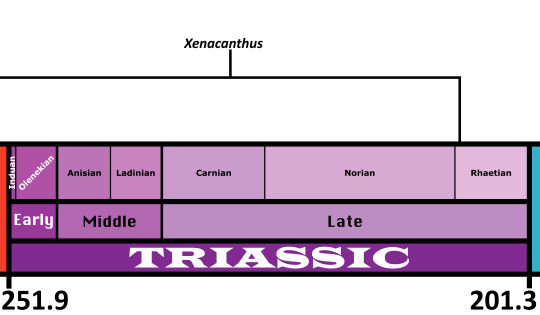

Time and Place: 295 to 208 million years ago, from the Sakmarian of the Early Permian to the Rhaetian of the Late Triassic.

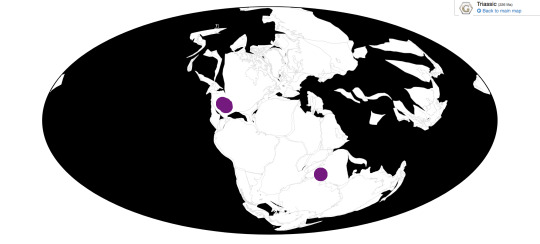

In the Triassic, Xenacanthus is known from New Mexico, Texas, and India.

Physical Description: Xenacanthus gets its name from the very large and narrow spike protruding out of the back of its head. Seriously, what’s up with that. Nobody really knows. Besidse that, the thing most people talk about are its teeth. Xenacanthid teeth are distinctively-shaped: they had a large oval base with two prongs shooting out, making the tooth look V-shaped. But beyond this, Xenacanthus is still interesting. The body is long and shallow, with ribbonlike dorsal and caudal fins that form an almost continuous fin going down the back and back up the bottom of the animal. The pectoral and pelvic fins are short and very broad.

Diet: Xenacanthus’s bizarre teeth may hint at a diet of crunchier foods. It likely ate fish and small invertebrates in the waters it lived, as well as potentially the carcasses of anything that drowned.

Behavior: Xenacanthus’s body is not well-equipped for fast swimming. Its pectoral and pelvic fins almost look limblike, and may have potentially been used to help maneuver (or “walk”) around river bottoms like modern epaulette sharks. Xenacanthus likely sat in the muddy bottoms of the rivers it lived in, waiting for prey to swim on by. Although it lived in rivers, Xenacanthus may have migrated to the sea to spawn like its relative Orthacanthus (and some living eels). The purpose of the spike on the back of the head is completely unknown, but it may have been used for display, defense, or stabilizing swimming.

Ecosystem: Xenacanthus lived in shallow freshwater environment such as seasonal rivers. It’s known from two areas in the Triassic: the southwestern United States, and India. In the southwestern US, it lived alongside the lungfish Ceratodus, various ray-finned fish, temnospondyls such as Metoposaurus and Koskinonodon, early dinosaurs like Coelophysis, dinosauromorphs such as Dromomeron, pseudosuchians such as Typothorax, Shuvosaurus, Postosuchus and Poposaurus, phytosaurs such as Rutiodon and Smilosuchus, and various other bizarre archosauromorphs like Vancleavea, Trilophosaurus, and Tanytrachelos. If this sounds familiar, this is because we’ve already featured lots of critters from Late Triassic North America. Lots of familiar faces.

Meanwhile in India, Xenacanthus lived alongside the hybodontid shark Polyacrodus, Ceratodus again, and the temnospondyl Buettneria. These rivers would have been frequented by thirsty amniotes such as the rhynchosaur Hyperodapedon, the protorosaur Malerisaurus, aetosaurs, the early dinosaur Alwalkeria, dicynodonts, the cynodont Exaeretodon, and that weirdo, you know it, you love it, Shringasaurus.

Other: Xenacanthus evolved in the Permian, and amazingly made it through the Great Dying! Sure, they were a lot more common in the Permian, but xenacanthids made it through to the end of the Triassic (when they were apparently done in by the end-Triassic extinction).

~ By Henry Thomas

Sources under the cut

Beck, K.G., Soler-Gijon, R., Carlucci, J.R., Willis, R.E. 2014. Morphology and Histology of Dorsal Spines of the Xenacanthid Shark Orthacanthus platypternus from the Lower Permian of Texas, USA: Palaeobiological and Palaeoenvironmental Implications. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61(1): 97-117.

Bhat, M.S. 2015. A new and diverse Late Triassic fish assemblage from India. International Conference on Current Perspectives and Emerging Issues in Gondwana Evolution, Lucknow.

Lucas, S.G., Heckert, A.B., Hotton, N. 2002. The rhynchosaur Hyperodapedon from the Upper Triassic of Wyoming and its global biochronological significance. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 21: 149-156.

Palmer, D. 1999. The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. Marshall Publishing, London.

Pauliv, V.E., Dias, E.V., Sedor, F.A., Ribeiro, A.M. 2014. A new Xenacanthiformes shark (Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii) from the Late Paleozoic Rio do Rasto Formation (Parana Basin), Southern Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias 86(1).

#xenacanthus#xenacanthid#shark#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#prehistoric life#paleontology

160 notes

·

View notes

Note

thank you :]]] !!!!

here's another shark fact

most sharks fossils from 300 to 150 million years ago were separated into two groups the xenacanthida which were exclusively saltwater sharks and who became extinct around 220 million years ago and the hybodonts which lived in both salt and freshwater

Sharks are cool!! :D do you have a shark fact you could share? :)

sharks r very cool !!!

i do have a shark fact, sharks were known as 'sea dogs' in the sixteenth century and the word 'shark' is deprived from the dutch schurk meaning 'villain' or 'scoundrel'

22 notes

·

View notes