#would you believe that i literally have a class discussing the labor movement and rise of communism in early 20th century america that ive

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

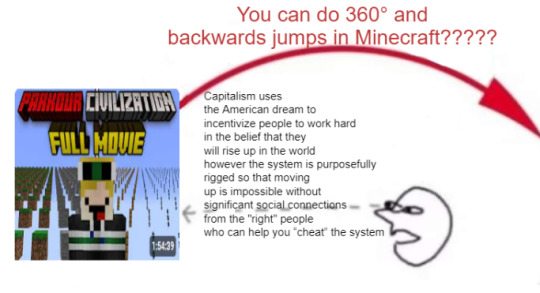

Do you think Evbo learned how to do those jumps and thought "oh this is so sick what's the best way I can show off my parkour skills"

#mcyt#maige's posts#maige's memes#parkour civilization#parkciv#evbo#this is my contribution to the fandom. god i love blond green boys who become burdened with the fate of the world when all they want to do#is be free and have fun#would you believe that i literally have a class discussing the labor movement and rise of communism in early 20th century america that ive#been ignoring bc i was too busy watching this#i have a 350 word essay due actually. oh shit

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

“In part girls’ extensive reading reflected new possibilities brought about by developments in the American reading public, the publishing industry, and the distribution of reading matter. Printing was one of those industries in nineteenth-century America—like the ginning and the weaving of cotton— that was transformed by technological advances. The result was a substantial increase in the production of books and a much wider distribution of those books, helped along also by the free library movement. High rates of literacy both encouraged and resulted from this increase in the availability of printed materials.

The American Revolution itself, many historians have argued, was galvanized by a public literate enough to read and debate the pamphlets issued by politicized journeymen printers. Women were not well represented among those numbers, though probably many women who could not write could read. In the decades immediately following the Revolution, the literacy rate among women rose dramatically. A study of rural Vermont in 1800 concludes that even away from urban areas ‘‘the proportion of women engaged in lifelong reading and writing had risen to about eighty percent.’’

With the opening of common schools in the nineteenth century, girls were educated the same ways that boys were—unevenly, sometimes at home, sometimes at school, but effectively. By 1880 reading literacy was claimed by 90 percent of the native-born American public and 80 percent of their foreign-born compatriots. The explosion of print in the nineteenth century was enabled by a variety of developments in both technology and distribution. Technological innovations in printing nourished the growth of the antebellum reading public.

The innovations of stereotyping and electrotyping preserved an ‘‘impressment’’ of the type once it had been set so that future editions would not require expensive resetting. The result was that before the Civil War the cost of books dropped to roughly half of their cost in the late eighteenth century. Although at seventy-five cents or more such a price was still too costly for skilled male laborers who earned only a dollar a day, and although inadequacy of lighting in many working-class homes helped to limit the Victorian reading public, a substantial proportion of Americans—those who were coming to constitute the aspiring middle class—were able to gain access to books.

Access to books did not define an American public, but increasingly it defined a class of those who hoped to rise in station. Improvements in printing technology fostered the growth of another literary genre, the periodical, which launched many novels in serialized form in both Britain and the United States. Periodicals in the United States and Britain budded in the early nineteenth century, and a number flowered at midcentury, feeding and fed by the literacy and leisure of Victorian readers. Included among these were a growing selection of magazines targeting special audiences, especially youth.

Youth’s Companion, founded in 1827, mustered the greatest longevity and the highest circulation, and it was joined by the influential St. Nicholas (1873), which amassed a distinguished group of writers. The preeminent magazine for women, Godey’s Ladies Book, achieved a circulation of 150,000 at its prime just before the Civil War. Girls and women provided much of the readership for the general family magazine as well, including Scribner’s, Harper’s Weekly, North American Review, and Century. Periodicals had the advantage of providing regular access to print for a reading-hungry populace and were especially cherished by those far away from lending libraries and those whose economic circumstances forced them to ration their reading.

…The public library movement expanded access to reading material beyond the ranks of the wealthy. Along with the growth of common-school education, libraries provided the institutional underpinning of the reading revolution. As early as the eighteenth century, groups of ambitious private citizens had united to share access to precious books. Later in the century clerks, merchants, and mechanics, too, gathered to form so-called ‘‘social libraries’’ which could be joined by payment of a fee.

It was to one of these libraries which Lois Wells, a resident of Quincy, Illinois, received a three-month subscription for her seventeenth birthday in 1886, probably because there was no public library in her town. The importance of an educated citizenry to a republic encouraged the founding of more free facilities, however. Beginning in Boston, and then expanding outward to New England and on to the Midwest, free libraries aimed to offer to all citizens the opportunity for uplift and self-culture which was previously available only to an elite.

The Boston Public Library opened its doors in 1854, and other cities followed suit in increasing numbers after the Civil War. States supported local efforts by passing legislation which would allow townships to divert public funds to the support of free libraries. A massive government report in 1876 listed 3,682 public libraries, a number which would rise to at least 8,000 by 1900. Access to public libraries was uneven, however, thinning out as one moved west and especially south from New England and the mid-Atlantic.

Taking up the slack between the vogue for reading and its limited supply, Sunday schools enhanced their appeal and ensured the quality of children’s reading matter by acquiring book collections and issuing weekly books to deserving students. When the American Sunday School Union and other religious publishers began issuing prepackaged ‘‘libraries’’ of their own publications in the midcentury (one hundred books for $10), the custom became even more prevalent—until eclipsed by the public-library movement itself.

…The project of self-culture did not regard all reading as equal, of course. The removal of girls from their mothers’ elbows as informal apprentices in housewifery meant a partial surrender of daughters to a national or trans-Atlantic culture. Advice givers subjected it to scrutiny, often discussing the appropriate fare for Victorian girls. In the United States, those standards became the defining standards for genteel culture as a whole.

Richard Gilder, the eminent publisher of Century, outlined the rules for his writers. ‘‘No vulgar slang; no explicit references to sex, or, in more genteel phraseology, to the generative processes; no disrespectful treatment of Christianity; no unhappy endings for any work of fiction.’’ Designed for reading aloud within the family circle, genteel fiction as a whole, but periodical literature in particular, had to pass what was named by poet Edmund Stedman the ‘‘virginibus’’ standard—whether it would be appropriate even for the unmarried daughters of a respectable bourgeois family to listen to or to read.

This reading program had some general precepts. Of course, religious literature of all kinds was favored for study and improvement. The old was better than the new, a rule that encouraged history, and for younger children, myths and legends. Seventy-three years old in 1880, the writer and woman’s rights advocate Elizabeth Oakes Smith suggested a conservative regimen for girls which included history, biography, constitutional and moral philosophy, geography, travel literature, science, and ‘‘the several branches of natural history which open up to the mind the wonders and mysteries of this beautiful world in which we live.’’

An advice giver twenty-five years later explained why myths were appropriate for children’s reading: they were ‘‘interpretive of the beautiful and useful in nature, of the high and noble impulses of the heart, and of the right in human intercourse.’’ The counsel to admire the beautiful and to seek the pure and the true left advice writers conflicted about the most popular genre on the reading lists of girls: the novel. The right novels had power to do much good. The British advice writer Henrietta Keddie recommended ‘‘without fail [Elizabeth Gaskell’s] Cranford, and Miss Austen’s books, to make you a reasonable, kindly woman.’’

The goal of such works was to discipline aspiration, however, for the exemplary woman would be ‘‘satisfied with a very limited amount of canvas on which to figure in the world’s great living tapestry.’’ Elizabeth Oakes Smith implored young girls to avoid the low road and ‘‘most of the fictions of the day,’’ admitting only ‘‘those based on the eras of history, such as the inimitable works of Walter Scott,’’ and the works of Dickens, which ‘‘may deepen our sympathy for the miserable and erring.’’

Another later counselor to young girls, Harriet Paine, in Chats with Girls on Self-Culture (1900) also challenged the appropriateness of realism: ‘‘Girlhood is not the time for any novelist who does not believe that something besides the actual is possible and necessary.’’ She too applauded Sir Walter Scott, who was always ‘‘to be trusted to present a natural world which is nevertheless rosy with the light of romance,’’ and Dickens: ‘‘I never knew a girl who loved Dickens who was not large-hearted.’’

Paine was more inclusive, though: ‘‘There are half a dozen fresh, sweet story-writers girls are always the better for reading,’’ and then she enumerated Louisa May Alcott and a number of British writers, including Dinah Mulock-Craik, Anne Thackeray, and Charlotte Yonge. Much fiction, however, did not grow ‘‘where the rose-tree blooms’’ but instead led young readers ‘‘through mire and dirt,’’ advisers cautioned. Genteel periodicals for youth contained some of the most pointed warnings to youths of both sexes about the dangers of inappropriate reading.

An outburst from St. Nicholas in 1880 warned that a craving for sensational fiction is more insidious, but ‘‘I am not sure that it is not quite as fatal to character as the habitual use of strong drink.’’ The reading of illicit fiction ‘‘weakens the mental grasp, destroys the love of good reading, and the power of sober and rational thinking, takes away all relish from the realities of life, breeds discontent and indolence and selfishness, and makes the one who is addicted to it a weak, frivolous, petulant, miserable being.’’

The power attributed to the vicarious excitement of the emotions remained something of a constant through the nineteenth century. Given such acknowledged dangers, how did girls get access to such books? The question of access played out in a debate over the holdings of public libraries. Librarians made up a new group of elite reformers who aimed to elevate the public intellect through their professional organization, the American Library Association.

In 1881, the ALA attempted to impose uniform censorship on the collections formed for the public good, and got as far as surveying major public libraries and compiling a list of sixteen authors ‘‘whose works are sometimes excluded from public libraries by reason of sensational or immoral qualities.’’ The list included twelve female domestic novelists—such popular writers as E. D. E. N. Southworth and Mary Jane Holmes. It did not go farther. The library ultimately compromised its genteel ambitions with the tastes of the public, and by the turn of the century reliably stocked what its readers wanted to read.”

- Jane H. Hunter, “Reading and the Development of Taste.” in How Young Ladies Became Girls: The Victorian Origins of American Girlhood

#victorian#education#american#censorship#libraries#jane h. hunter#how young ladies became girls#history

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

notes on graeber’s bullshit jobs

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the value of work and about the work I’m going to (have to) be doing — what makes it useful, how can i make it useful, and what does it mean to do valuable work? How can I know if the work I do creates negative social value? I’ve been afraid of coming back, not because I’m afraid of starting work, but because of what that is suppoed to signify. And about all the shit I’m going to have to swallow on account of “this is just how things are.” Graeber talks about:

The dummy jobs that pass for real work – he lists five categories whose common denominator is that, basically, nothing would happen if the worker (within a company) decides one day not to show up to work anymore or if all the workers (at the level of industry — this is levied against the FIRE industry), life won’t grind to a halt. He talks about “managerial feudalism” and the rise of the manager roles and people who are literally paid to “look busy.”

The myth of being “on somebody else’s time” which says that since you’re being paid for your time, you shouldn’t be doing anything else, even if you have nothing to do. And the absence of real work as quite literally de-humanizing and contravenes/contradicts the human need for purpose.

The myth of needing to seem busy and value as appearing productive: “My mind keeps going back to the pressure to value ourselves and others on the basis of how hard we work at something we’d rather not being doing. I believe this attitude exists in the air around us. We sniff it into our noses and exhale it as a social reflex in small-talk; it is one of the guiding principles of social relations here: if you’re not destroying your mind and body via paid work, you’re not living right.” (198)

The difficulty that people in such jobs have of even expressing their displeasure without being told to fuck off and be grateful they even have a job. [Very familiar]

How we got here and the history of production, e.g. puritan work ethic, hard work = character formation and the theological (judeo-christian – i mean just look at genesis lmao) roots of work, how this continued into the industiral revo – e.g. carlyle’s gospel of work. Specifically, work/labour as self-abnegation, something that is deliberately supposed to be punishing and not pleasurable – i.e. very Carlyle – “Workers, in other words, gain feelings of dignity and self-worth because they hate their jobs.” (221) And how “life” [think about the whole bs about work-life balance] as something that has to be “eked out” in the temporal spaces between periods of work.

And also how seeing labor as The Male Factory Worker – “both the words “production” and “reproduction” are based on the same core metaphor: in the one case, objects seem to jump, fully formed, out of factories; in the other, babies seem to jump, fully formed, out of women’s bodies.” (203) He sees the original labor theory of value as gendered bc it focused on production and so erased women’s work.

Or more specifically, work that women are expected/typically thought to do, e.g. “looking after people, seeing to their wants and needs, explaining, reassuring, anticipating what the boss wants or is thinking, not to mention caring for, monitoring, and maintaining plants, animals, machines, and other objects, than it involves hammering, carving, hoisting or harvesting things.” (215)

The gap between work that creates social value and how they are valued ($$), resulting in “carping labor” or “interpretive labor” being un/undervalued and which markets don’t pick up on because markets are always looking for things being produced, being made and being put out into the world. i.e. “caring labor” has been not just undervalued but completely overlooked because “values […] are valuable [exactly] because can’t be reduced to numbers.” (241)

The difficulty of organizing movements around “bullshit jobs” and also the contradiction between care and stability: even if, logically, we can wake up one day and decided to change things, to stop “producing capitalism,” which is not something abstract and impersonal but something we create everyday, “love for others — people, animals, landscapes — regularly requires the maintenance of institutional structures one might otherwise despite.” (219)

And what can be done about it: He points to a “crisscrossing of resentment” that proliferates within the world of work, and also acknowledges an inertia for change and also to barrier to actually admitting your job is bullshit, that it’d be better if robots just took over etc.

He makes an interesting point on the division between the workplace as the “domain of production” and the home as the “domain of consumption” and “the domain of values (which means that what work people do engage in, in this domain, they largely do for free)”, and which obviously has a gendered dimension too! Graeber published in 2018 but it’ll be interesting to relook this idea within the context of the pandemic, in which work and home are so thoroughly meshed.

#5 was particularly painful for me to read because it put in another way what I’d already known ��� or rather what took me all these years away from singapore recovering from how much i’d let the education system fuck me up to realise. There was a time when I glorified hard work and self-punishment and I was so fixated on the idea of academic rigour and challenge that I went all out and lost any idea of what actually made / could make me happy. Somehow convinced myself that enjoyment = slaving over something and overcoming that challenge, i.e. econ. Something had to be difficult to be worth it — to be real work — because if i didn’t have to slave over it, if i didn’t have to work myself to death for it, AND if i had fun doing it (i.e. literature), then it wasn’t real work. There was a belief that value could only come by sacrificing a part of myself — in high school, it was a real, visceral happiness. I believed that i could postpone being happy to after those final exams. And the hard work had to be painful and self-effacing, and which in turn ought to be worn as some sort of a badge of honor on my identity and sense of self-worth (Graeber: “sadomasochistic dialectic”).

#11: I wonder if the way things are panning out in this pandemic is (the beginning of? the conditions for?) the “revolt of the caring classes” (242) that Graeber wonders about towards the end of the chapter? We see nurses asking for more pay and I’m reminded of this article in The Atlantic. The pandemic has shifted the nature of work by opening up options for remote work and more improtantly drawing into sharp relief the work that cannot be done from home — the work that requires care and contact — and which has so conveniently been overlooked. People whose workplaces were never closed.

This includes those done by foreign workers in singapore. There’s one strand of rhetoric about the foreign worker situation in Singapore that goes something like, their working and living conditions are far worse at home, so they already have it good. Some activists have discussed the false premises of this argument, e.g. the assumption that workers “know” what they are getting into. Implicit in that logic is the assumption that giving them less than ideal work/living/wage conditions (read: exploitation) is normal — in Graeber’s words, “such is the nature of the sacrifice” they are making by coming here to eke out a better living for their families back home. One group that I’m also thinking about is foreign domestic workers, for whom the boundary between workplace and home was always absent. Foreign domestic workers take over the “caring labor” that usually done for free by those in the home, but they are severely unpaid for the work that they do. There are all these stories about how they can’t even rest and relax because of the logic that they’re on the employer’s time and occupying the employer’s space. Is it about paying them more? Maybe, but it’s also a question of why aren’t we already paying them more? This is caught up again with exploitation and class, and within Singapore with our reliance on low-wage workers to fill labor-intensive jobs so the rest of us can go on with the sort of bullshit ones that Graeber talks about. And becuase they are not paid highly, the work they do is not valued ($$).

Anyway in may 2020, I’m less interested in how the pandemic lets me work from home in my pjs as how it challenges the inertia for redressing power imbalances.

0 notes

Text

America Must Prepare for the Coming Chinese Empire

The last thing American policymakers or strategists should assume is that somehow Americans are superior to the Chinese.

by

Robert D. Kaplan

BEFORE ONE can outline a grand strategy for the United States, one has to be able to understand the world in which America operates. That may sound simple, but a bane of Washington is the assumption of knowledge where little actually exists. Big ideas and schemes are worthless unless one is aware of the ground-level reality of several continents, and is able to fit them into a pattern, based not on America’s own historical experience, but also on the historical experience of others. Therefore, I seek to approach grand strategy not from the viewpoint of Washington, but of the world; and not as a political scientist or academic, but as a journalist with more than three decades of experience as a reporter around the globe.

After covering the Third World during the Cold War and its aftershocks which continue to the present, I have concluded that, despite the claims of post-colonial studies courses prevalent on university campuses, we still inhabit (in functional terms, that is) an imperial world. Empire in some form or another is eternal, even if European colonies of the early-modern and modern eras are gone. Thus, the issue becomes: what are the contours of the current imperial age that affect grand strategy for the United States? And once those contours are delineated, what should be America’s grand strategy in response? I will endeavor to answer both questions.

Empire, or its great power equivalent, requires the impression of permanence: the idea, embedded in the minds of local inhabitants, that the imperial authorities will always be there, compelling acquiescence to their rule and influence. Wherever I traveled in Africa, the Middle East and Asia during the Cold War, American and Soviet influence was seen as permanent; unquestioned for all time, however arrogant and overbearing it might have been. Whatever the facts, that was the perception. And after the Soviet Union collapsed, American influence continued to be seen for a time as equally permanent. Make no mistake: America, since the end of World War II, and continuing into the second decade of the twenty-first century, was an empire in all but name.

That is no longer the case. European and Asian allies are now, with good reason, questioning America’s constancy. New generations of American leaders, to judge from university liberal arts curriculums, are no longer being educated to take pride in their country’s past and traditions. Free trade or some equivalent, upon which liberal maritime empires have often rested, is being abandoned. The decline of the State Department, ongoing since the end of the Cold War, is hollowing out a primary tool of American power. Power is not only economic and military: it is moral. And I don’t mean humanitarian, as necessary as humanitarianism is for the American brand. But in this case, I mean something harder: the fidelity of our word in the minds of allies. And that predictability is gone.

Meanwhile, as one imperium-of-sorts declines, another takes its place.

China is not the challenge we face: rather, the challenge is the new Chinese empire. It is an empire that stretches from the arable cradle of the ethnic Han core westward across Muslim China and Central Asia to Iran; and from the South China Sea, across the Indian Ocean, up the Suez Canal, to the eastern Mediterranean and the Adriatic Sea. It is an empire based on roads, railways, energy pipelines and container ports whose pathways by land echo those of the Tang and Yuan dynasties of the Middle Ages, and by sea echo the Ming dynasty of the late Middle Ages and early-modern period. Because China is in the process of building the greatest land-based navy in history, the heart of this new empire will be the Indian Ocean, which is the global energy interstate, connecting the hydrocarbon fields of the Middle East with the middle-class conurbations of East Asia.

This new Indian Ocean empire has to be seen to be believed. A decade ago, I spent several years visiting these Chinese ports in the making, at a time when few in the West were paying attention. I traveled to Gwadar in the bleak desert of Baluchistan, technically part of Pakistan but close to the Persian Gulf. There, I saw a state-of-the-art port complex rising sheer above a traditional village. (The Chinese are now contemplating a naval base in nearby Jawani, which would allow them to overwatch the Strait of Hormuz.) In Hambantota, in Sri Lanka, I witnessed hundreds of Chinese laborers literally moving the coast itself further inland, as armies of dump trucks carried soil away. While America’s bridges and railways languish, it is a great moment in history to be a Chinese civil engineer. China has gone from building these ports, to having others manage them, and then finally to managing them themselves. It has all been part of a process that recalls the early days of the British and Dutch East India companies in the same waters.

Newspaper reports talk of some of these projects being stalled or mired in debt. That is a traditionally capitalist way to look at it. From a mercantile and imperialist point of view, these projects make perfect sense. In a way, the money never really leaves China: a Chinese state bank lends the money for a port project in a foreign country, which then employs Chinese state workers, which utilize a Chinese logistics company, and so on.

Geography is still paramount. And because the Indian Ocean is connected to the South China Sea through the Malacca, Sunda and Lombok straits, Chinese domination of the South China Sea is crucial to Beijing. China is not a rogue state, and China’s naval activities in the South China Sea make perfect sense given its geopolitical and, yes, its imperial imperatives. The South China Sea not only further unlocks the Indian Ocean for China, but it further softens up Taiwan and grants the Chinese navy greater access to the wider Pacific.

The South China Sea represents one geographical frontier of the Greater Indian Ocean world; the Middle East and the Horn of Africa represent the other. The late Zbigniew Brzezinski once wisely said in conversation that hundreds of millions of Muslims do not yearn for democracy as much as they yearn for dignity and justice, things which are not necessarily synonymous with elections. The Arab Spring was not about democracy: rather, it was simply a crisis in central authority. The fact that sterile and corrupt authoritarian systems were being rejected did not at all mean these societies were institutionally ready for parliamentary systems: witness Libya, Yemen and Syria. As for Iraq, it proved that beneath the carapace of tyranny lay not the capacity for democracy but an anarchic void. The regimes of Morocco, Jordan and Oman provide stability, legitimacy, and a measure of the justice and dignity that Brzezinski spoke of, precisely because they are traditional monarchies, with only the threadbare trappings of democracy. Tunisia’s democracy is still fragile, and the further one travels away from the capital into the western and southern reaches of the country, close to the Libyan and Algerian borders, the more fragile it becomes.

This is a world tailor-made for the Chinese, who do not deliver moral lectures about the type of government a state should have but do provide an engine for economic development. To wit, globalization is much about container shipping: an economic activity that the Chinese have mastered. The Chinese military base in Djibouti is the security hub in a wheel of ports extending eastward to Gwadar in Pakistan, southward to Bagamoyo in Tanzania, and northwestward to Piraeus in Greece, all of which, in turn, help anchor Chinese trade and investments throughout the Middle East, East Africa and the eastern Mediterranean. Djibouti is a virtual dictatorship, Pakistan is in reality an army-run state, Tanzania is increasingly authoritarian and Greece is a badly institutionalized democracy that is increasingly opening up to China. In significant measure, between Europe and the Far East, this is the world as it really exists in Afro-Eurasia. The Chinese empire, unburdened by the missionary impulse long prevalent in American foreign policy, is well suited for it.

MORE TO the point, when it comes to China, we are dealing with a unique and very formidable cultural organism. The American foreign policy elite does not like to talk about culture since culture cannot be quantified, and in this age of extreme personal sensitivity, what cannot be quantified or substantiated by a footnote is potentially radioactive. But without a discussion of culture and geography, there is simply no hope of understanding foreign affairs. Indeed, culture is nothing less than the sum total of a large group of people’s experience inhabiting the same geographical landscape for hundreds or thousands of years.

Anyone who travels in China, or even observes it closely, realizes something that the business community intuitively grasps better than the policy community: the reason there is little or no separation between the public and private domains in China is not only because the country is a dictatorship, but because there is a greater cohesion of values and goals among Chinese compared to those among Americans. In China, you are inside a traditional mental value system. In that system, all areas of national activity—commercial, cyber, military, political, technological, educational—work fluently toward the same ends, so that computer hacking, espionage, port building and expansion, the movement of navy and fishing fleets, and so on all appear coordinated. And within that system, Confucianism still lends a respect for hierarchy and authority among individual Chinese, whereas American culture is increasingly about the dismantling of authority in favor of devotion to the individual. Confucian societies worship old people; Western societies worship young people. One should never forget these lines from Solzhenitsyn: “Idolized children despise their parents, and when they get a bit older they bully their countrymen. Tribes with an ancestor cult have endured for centuries. No tribe would survive long with a youth cult.”

Chinese are educated in national pride; increasingly the opposite of what goes on in our own schools and universities. And Chinese are extraordinarily efficient, with a manic attention to detail. Individuals are certainly more concrete than the mass. But that does not mean national traits simply do not exist. I have flown around China on domestic airlines with greater ease and comfort than I could ever imagine flying around America at its airports. And that is to say nothing about China’s bullet trains.

Of course, there are all sorts of political and social tensions inside China. And the unrest among the middle classes we see today in Brazil and the rest of Latin America could well be a forerunner to what we will see in China in the 2020s, undermining Belt and Road and the whole Chinese imperial system altogether. China’s over-leveraged economy may well be headed for a hard, rather than a soft, landing, with all the attendant domestic upheaval which that entails. I have real doubts about the sustainability of the Chinese political and economic model. But the last thing American policymakers or strategists should assume is that somehow we are superior to the Chinese, or worse: that somehow we have a destiny that they do not.

WE HAVE entered a protracted struggle with China, which hopefully will not be violent at certain junctures. And it may become more dangerous precisely because China could weaken internally due to economic upheavals, causing its leaders to dial up nationalism as a default option. It will be a struggle (or war) of integration rather than of separation. Throughout the human past, wars have seen an army from one place and an army from another place meet somewhere in the middle to give battle. However, in the cyber age, we are all operating inside the same operating environment, so that computer networks can attack each other without armies ever meeting or even blood being shed. The Russian attempt to influence our politics is an example of war by integration, which could not have existed even two decades ago. The information age has added to the possibilities for warfare rather than subtracted from it. The enemy is only a click away, rather than hundreds of miles away. And because weapons systems require guidance from satellites, outer space is now a domain for warfare, just as the seas became once the Portuguese and Spanish had begun the Age of Exploration. Every age of warfare has its own characteristics. Increasingly, warfare has become less physical and more mental: the more obsessively driven the culture, the better suited it will be for mid-twenty-first-century cyber warfare. If that seems offensive to the reader, remember that the future lies inside the silences—inside the things we are most uncomfortable talking about.

In functional and historical terms, this will be an imperial struggle, though our elites both inside and outside government will forbid use of the term. The Chinese will have an advantage in this type of competition as they have a greater tradition in empire building than we do, and they are not ashamed of it as we have become. They openly hark back to their former dynasties and empires to justify what they are doing; whereas our elites can hark back less and less to our own past. Westward expansion, rather than the heroic saga portrayed by mid-twentieth-century American historians, is now often taught as a tale of genocide against the indigenous population and nothing more—even though without conquering the West, we never would have had the geopolitical and economic capacity to win World War I, World War II and the Cold War.

Moreover, the Chinese have demonstrated an ability to quickly adapt, which is the key to Darwinian evolution: the continual changes that they are making to their Belt and Road model are an example of this.

The Chinese also have more capable leadership than we do.

Undeniably, our post-Cold War presidents have been dramatically inferior to our Cold War presidents in terms of thinking strategically about foreign affairs. Bill Clinton was not altogether serious about foreign policy, especially at the beginning of his presidency; George W. Bush was in significant measure a failure at it; Barack Obama too often seemed to apologize for American power; and Donald Trump is frankly unsuited for high office in the first place. Compare them to Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Nixon, Reagan and the elder Bush. Compare, too, our post-Cold War presidents to Chinese leader Xi Jinping. Xi is disciplined, strategically minded, unashamed of projecting power, an engineer by training, with living experience in the provinces, and perhaps, most importantly, someone with a deep sense of the tragic, as his family was a victim of Mao Zedong’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. This is a man of virtu, in the classical Machiavellian sense. One could go further and say that there is not only a crisis in American leadership but in Western leadership in general. The truly formidable, dynamic leaders, whatever their moral values, are more likely to be found outside the United States and Europe. Witness, in addition to Xi, Japan’s Shinzo Abe, India’s Narendra Modi, Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu. They have all grasped the art of power; they are constantly willing to take risks, and they are in office not only out of personal ambition but because they actually want to get certain things done.

Thus, the competition between the United States and China will coincide with a political-cultural crisis of the West against a resurgent East.

We have truly entered an American-Chinese bipolar struggle. But it is a bipolar struggle with an asterisk: the asterisk being Russia, which can always inflict consequential damage on the United States. Yet, whereas the Russians appear to our media as classic bad guys, the Chinese are more opaque and business-like, so the gravity of our competition with Beijing is still insufficiently appreciated by our media.

TRULY, THE sense of invulnerability the United States felt at the end of the Cold War and the onset of globalization is gone. Initially, post-Cold War globalization meant a Westernization of the world to go along with the adoption of Western-style management practices and America’s so-called unipolar moment. Now that this moment has passed, and with middle classes enlarging throughout the developing world—while different shades of authoritarianism compete with democracy—globalization is becoming more multicultural, with the East assuming an equal position, helped also by demographic trends. In this competition, the United States is wrong to promote democracy per se. Instead, it should promote civil society whether democratic or of the enlightened authoritarian mode. (Witness the liberalizing yet authoritarian monarchies of Morocco, Jordan and Oman. And I could give examples beyond the Middle East.) Hybrid regimes of an enlightened authoritarian mode have been more of a norm throughout history than democracy has been. Moreover, it has been my clear experience that people in Africa and the Middle East care first about basic order and physical and economic protection before they care about political freedoms. As the late liberal philosopher Isaiah Berlin writes: “Men who live in conditions where there is not sufficient food, warmth, shelter, and the minimum degree of security can scarcely be expected to concern themselves with freedom of contract or of the press.”

Obviously there exists a hierarchy of needs, and meaningful improvement in people’s lives as a first priority should demand flexibility on our part—or else it will be harder to compete with the Chinese. The expansion of middle classes worldwide will by itself lead to greater calls for democracy: for as people’s material lives improve they will increasingly demand more political freedoms anyway. We do not need to force the process. If we do, it will be we who are the ones being ideological; not the Chinese, who have the civilizational confidence and serenity to accept political systems as they already are.

Yet, even at our worst, our political system is open and capable of change in the way that China, and that other great autocratic power, Russia, are not. A world in which the United States is the dominant power will be a more humane world of more personal freedoms than a world led by China.

I concentrate on China in this essay because China constitutes a much stronger economy, a much more institutionalized political system, and a more formidable twenty-first-century cultural genius than Russia. Therefore, China should be the yardstick or pacing power by which our diplomatic, security and defense establishments measures themselves: merely by competing with China we will make our own institutions stronger. Such competition is all that might be left to jolt our bureaucracies out of their ongoing decrepitude and decline. Indeed, the profusion of travel orders, security clearance paperwork, unnecessary receipts, and so forth, even as the hacking of our systems continues, are all ways in which we deliberately deceive and defeat ourselves. Paperwork arises out of the lack of trust. The more paperwork, the less trust that exists within a bureaucracy. The Pentagon is a prime example of this. We should always remember that there is no regulation or procedure to instill basic common sense.

One priority should be to effectively get out of the Middle East. Every extra day that the United States is diverted and bogged down in the Middle East with significant numbers of ground troops helps China in the Indo-Pacific and Europe even, where China is working to establish powerful commercial shipping footholds in places like Trieste on Italy’s Adriatic shore and Duisburg in riverine Germany; to say nothing about promoting its 5G digital network. I don’t mean to say that we should pull all our forces out of the Middle East tomorrow. I mean that our goal should be to reduce our military footprint as quickly as practically possible, whenever and wherever possible.

For example, the United States has had combat troops in Afghanistan for almost two decades with no demonstrable result. The future of Afghanistan will be decided by competing ethnic alliances within that country, and Indians and Iranians squaring off against Chinese and Pakistanis. The Indians and Iranians will build an energy and transport corridor from Chah Bahar in southeastern Iran north through western Afghanistan into former Soviet Central Asia. The Chinese and Pakistanis will try to build another such corridor from Gwadar in southwestern Pakistan north, parallel with the Afghan border, to Kashgar in western China. In particular, Pakistan, which will always require Afghanistan as a rear base against India, must, therefore, struggle against India in Afghanistan. India, whose own imperial past encompasses the eastern half of Afghanistan, will do everything possible to thwart Pakistan there. Russia, which lies just to the north of Afghanistan, will also play a role because of its interest in smothering radical Islam. A great game is about to ensue in Afghanistan in which the United States will play absolutely no part, regardless of how much blood it has shed there, because it lacks a geographical basis for it, and therefore has little or no national interest at stake.

All we can do is help stabilize Afghanistan so that the Chinese and others can more safely continue to establish mining and other operations in the country. In any case, building a strong central government in Afghanistan may prove chimerical since none has ever existed in Kabul. The city has traditionally functioned as a central point of arbitration for the various warlords and tribal leaders that have exercised effective control in southern Central Asia. Covering the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s, I saw vividly how the Soviets lost because the mujahidin enemy, a diverse collection of tribal-based groups which viciously distrusted each other, provided the Soviets with no useful point of attack. Afghanistan’s very disorganization defeated the Soviets, just as it has been defeating us.

Iran, of course, so populous and well-educated, and fronting not one but two hydrocarbon-rich zones (the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea), is the demographic, economic and cultural organizing principle of both the Middle East and Central Asia. But what happens inside Iran will be internally driven. Iranians have a civilizational sense of themselves equal to that of the Indians, Chinese and Japanese. Even dramatic American diplomatic actions, like signing a nuclear deal with it, and later abrogating that same deal, can have only a marginal effect on Iran’s confoundedly-complex domestic politics in a country of over eighty million people. Despite periodic street demonstrations which will continue, the very institutionalized strength of the Revolutionary Guard Corps and other regime organizations make Iran perhaps the most stable big state in the Muslim Middle East.

As for Iraq, the inching forward of political stability there, however messy and fragile, has had relatively little to do with what the United States has done; or has not done. In fact, improvement in the Iraqi political situation has, for the most part, occurred despite American actions; not because of them. One American president destabilized Iraq by toppling its totalitarian ruler. The next American president further destabilized it by suddenly withdrawing American troops. Thus, from the anarchy of Iraq after Saddam Hussein came for a time the tyranny of the Islamic State. It was the experience of living under the Islamic State that convinced many Sunnis that they were better off allying with Shiites than with radicals of their own sect. It is this fact that has given Iraq some measure of hope and stability. True, American special operations forces helped a moderate Shiite leader defeat the Islamic State. But this moderate Shiite leader was subsequently defeated at the polls. In short, Iraq will determine its own destiny, influenced by Iran, the great power next door. American influence will remain marginal, whether or not we have any troops there. I say this as someone who initially supported the invasion of Iraq, which I have come to bitterly regret.

As for Syria, Bashar al-Assad has reconsolidated power in the only part of Syria that ultimately counts: its main population centers. Israel, buttressed by massive American military and economic aid, will be able to deal with the Iranian presence in Syria on its own. If the Russians want to get bogged down in Syria for the sake of their decadeslong investment in the Assad family regime, good luck to them. And by the way, Israel, unlike the United States, has a workmanlike, albeit problematic, relationship with Russia which it can employ as a go-between with Iran. The United States benefits very little by diverting time and resources to Syria.

The United States needs to end its adventures in the Middle East begun immediately after 9/11. Of course, the Chinese hope we never leave the Middle East. For if we deliberately defeat ourselves by remaining militarily engaged in the Middle East, it will only ease China’s path to global supremacy. Indeed, China would like nothing better than a war between the United States and Iran. China is already Iran’s largest trading partner and is pouring tens of billions of dollars into port, canal, and other development projects in Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula, proving how America’s military involvements in the region have gotten it virtually nowhere.

NO PLACE in the Muslim Middle East can serve as a litmus test of how we are doing vis-à-vis China the way that India and Taiwan can. They are the pivots that will go a long way to determining the strength of the American position in the Indo-Pacific: the first-among-equals when it comes to global strategic geography.

India is not a formal American ally and should not become one. India is too proud and too geographically close to China for that to be in its interest. But India, merely on account of its growing demographic, economic and military heft, along with its location dominating the Indian Ocean, acts as a natural balancer to China. Therefore, we should do everything we can to enable the growth of Indian power, without ever even mentioning a formal alliance with it. An increasingly strong India that gets along with China while never moving into China’s orbit—and is informally aligned with the United States—will be a sign that China is contained.

Taiwan has been a model ally, a stable and vibrant democracy, and one of the world’s most prosperous, efficient economies. It is a successful poster child for the liberal world order that the United States has built and guaranteed in Asia and Europe since World War II. Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger opened relations with China, but did so without endangering Taiwan. Therefore, if it ever became clear that the United States was both unable and unwilling to defend Taiwan in the event of a Chinese military attack on the island—or that an authoritarian China had consolidated its grip on Taiwan without the need of such an attack—then it would signal the end of American strategic dominance in East Asia. Countries from Japan in the north to Australia in the south would have no choice but to seek compromising security assurances from China in the event of such an eclipse of American power. This would be an insidious process often outside the strictures of the news headlines, but one day we would all wake up and realize that Asia has been partly Finlandized and the world had changed. Chinese domination of Taiwan would also, by the way, virtually confirm China’s effective domination of the South China Sea, which, together, with its port building activities to the east and west of India, would help give the Chinese navy unimpeded access to two oceans.

Grand strategy is about recognizing what is important and what is not important. I am arguing that, given our goals, India and Taiwan are ultimately more significant than places like Syria and Afghanistan. (Regarding Russia, because it is not almost at war with China as it was when the Nixon administration played the two communist regimes off against each other, moving closer to Russia now achieves little, though stabilizing our bilateral relationship is in our interest.)

WHEREAS INDIA and Taiwan are greatly affected by American sea power, the desert immensities of the Middle East are much less so. This is not an accident, but indicates something crucial. In a century when we will try to stay out of debilitating land conflicts that require large armies, we are better off relying on our navy which can project power without dragging us into bloody wars nearly as much. It is the U.S. Navy that will counter Chinese power along the semi-circle of the navigable Eurasian rimland, from the eastern Mediterranean to the Sea of Japan. And with less of a chance of drifting into costly military conflicts, we will have a better possibility of healing and invigorating our democracy at home. This is what grand strategy is fundamentally about.

Grand strategy is not about what we should do abroad. It is about what we should do abroad consistent with our economic and social condition at home.

Now, keep in mind my own, three-year rule. No matter how necessary and inspiring a military conflict, the American public will only give policymakers three years to settle it. America’s involvement in World War I lasted little more than eighteen months. In World War II, United States troops did not arrive in the Eastern Hemisphere until 1942, and by the Battle of Okinawa in 1945 there was public clamoring to end the Pacific war (as the war in Europe had already ended). The Korean War began in 1950 and by 1952 was unpopular, with Eisenhower forced to end it in 1953. American troops landed in large numbers in Vietnam in 1965 and the public turned against that war in 1968. The Iraq War was launched in 2003 and the public turned against it in 2006. We should aim never to test this three-year rule again. (In Afghanistan, we were able to break the rule only because we brought casualties down dramatically.) That means keeping a prolonged rivalry with China nonviolent in terms of blood-cost. We should engage on a number of fronts: cyber, economic, naval, diplomatic and so on, without open warfare. This can be achieved by not making a fetish out of the South China Sea. The U.S.-China relationship is too wide-ranging and organic to be reduced to a military dispute about one region. Military, trade and other areas of contention should not be kept in silos, since they can indeed interact.

To repeat, grand strategy for the United States in the twenty-first century is, in the end, about restraining from violence in order to concentrate on the home front, and yet compete with China at the same time: which, in turn, means recognizing certain geographical imperatives. (Of course, there is also the realm of ideas: so that it is tragic that President Trump abrogated the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which as a free-trading alliance would have given us a big idea to compete with Belt and Road.)

For some states and empires, which are victims of geography rather than blessed by it—Byzantium, Habsburg Austria—grand strategy is a necessity for survival. Contrarily, America’s geographical blessings have meant it can incur one disaster after another without paying a commensurate price. But as technology shrinks distance, enmeshing our continental half-island deeper into an unstable world, the United States finally becomes truly vulnerable: meaning it can no longer afford heroic delusions.

Consider: during the Cold War we didn’t need to worry about grand strategy because we already had one. It was called containment. George Kennan eschewed the hot-headed approach of those in the late-1940s and early-1950s who believed that it was possible to defeat the Soviet Union by subversion, special operations forces and other such desperate measures. Kennan understood that since Soviet Communism was fundamentally flawed as a system of governance, it would eventually falter and all we had to do was outlast it (just as we are likely to outlast Communist China if only we are patient). Thus, blessed by geography for so long, and blessed by a wise and temperate grand strategy for over four decades, we lost the art of thinking critically about ourselves, which, once again, is also what grand strategy is ultimately about.

Unable to look ourselves in the mirror and see our flaws and limitations, we concentrated too much on our military, and invaded or intervened in one Muslim country after another in the 2000s and achieved nothing as a result. Intervening in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s was successful in stopping a war, but the creation of ethnic cantons that followed did not lay a groundwork for the future, and even if it had done so, that would not have risen to the level of grand strategy given Yugoslavia’s secondary importance. So we are starting from scratch.

Starting from scratch means realizing that however inspiring the dreams of our elite are, those dreams will be stillborn if not grounded in both granular, local realities around the world and widespread public support at home that spans party lines—and that must be sustained over the long-term. We must be respectful of local realities, whether in Wyoming or Afghanistan.

Robert D. Kaplan is a managing director for global macro at Eurasia Group. His most recent book is The Return of Marco Polo’s World: War, Strategy, and American Interests in the Twenty-first Century.

0 notes