#with everyone’s trauma it makes their less than stellar actions make sense

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Can we just accept that every fucking character in ACOTAR has their faults?? Everyone is morally grey 😭

I recently joined the fandom and I am terrified to post a single thing. I feel like I’m gonna get hate over how I feel over anybody in that stupid book.

IM SO FR, THERES SO MANY CONFLICTING POSTS OF EVERY FUCKING CHARACTER

JUST ACCEPT THAT THEY ALL HAVE TRAUMA AND ISSUES THAT MAKE THEM REACT HARSHLY

#acotar#acomaf#acosf#acowar#acofas#sarah j maas#all the characters suck but don’t#ITS JUST THE PERSPECTIVE#i feel like i’m going insane#SEND HELP#except Rhysand#he’s just tryna be with his mate#����♀️#with everyone’s trauma it makes their less than stellar actions make sense#idk man#i suck at writing#I also suck at communicating#😭

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

What help do you think Shigure needs? Compared to everyone else his only trauma was getting cheated on.

(Note, I’m trying not to spoil too much here with my responses, so, for now, Akito’s going to be named in the third person, and I’m gonna try to answer without giving away too much.)

Mostly for his manipulative behavior and the way he tends to use others. He’s not exactly the best person when it comes to caring about others’ needs unless they are for his own wants and desires. Typically I think that he tends to see the world in an “All for me” sort of mentality. See the latest episode for examples of his less than stellar behavior. While yes, one can say that he’s worried about Tohru since he does have empathy in that black heart of his, the major reason for his actions with the boys wasn’t simply to get them to go back for her own good. No, he wanted them gone to make Akito feel like crap. He enjoys it when Akito’s in pain because he wants Akito all to himself.

One thing about the dog as a zodiac sign is that they are the Libra, this means that on the one hand they are loyal and probably one of the few that will seek compromise when it comes to decisions, and in some cases can’t make up their minds. They are also really cunning, and on the bad side, they get jealous. Thing is that that jealousy comes out as passive aggressive, as we see with Shigure when he basically blames Akito for the fact that Yuki and Kyo didn’t come. Had Akito been kinder, nicer, etc, or more willing to see him as he wants Akito to see him, in his mind the other two would be there and Akito could be happy. But he doesn’t want that totally either because he wants the curse gone so he doesn’t have to share Akito.

It’s a really really twisted love that he feels, and it’s part of the problem with the curse itself. There’s a really great Tumblr out there that covers the curse in more detail and the cannon. I’ll try to edit this once I find the link to it,( Edit: Found it! Fruuba Cannon) but suffice it to say that this curse is part of the reason Shigure probably has as rotten a personality as he does.

Yeah, his only trauma was being cheated on, true enough, but that’s not exactly a weak sort of trauma. Sure compared to say Kyo or Yuki, it may seem like a very limited thing, but if you look at what his life was like then that cheating was a huge thing for him emotionally. Think about it, Shigure is one of only 4 members of the Zodiac that are the same age roughly and is one of the few that knows the truth about who Akito really is. He was cheated on by the one that is the “god” who the curse is making him love in a way that he can’t refuse the feelings. (Hatori is an example here because even though Akito hurt him, he couldn’t hate Akito for what they did due to the fact that as the god the spirit in Hatori is compelled to love the god, so even though Hatori probably felt loathing for Akito in some way, he couldn’t fully because of the curse so let them get away with their actions because of his love for Akito as the god.)

The same thing compelled Shigure and his actions. Akito knew how to hurt him and went for the gut by cheating on him with the one member of the Zodiac that they knew would cause the most pain for him, the one that previously had been following and looking up to Shigure as a big brother. If it had been either of the other two I think he could have taken it because of his relationship with them. He would have seen it as Akito throwing a temper tantrum and waved it off in some way. But because it wasn’t one of the other two of the trio, that hit him worse. Cheating may normally not be insanely traumatic (though in some cases I’m sure it is, a spouse cheating with a best friend or sibling, or parent for example,etc), but it can be in certain cases, and with Shigure I have the feeling it was just as bad, if not worse to him emotionally, than Hatori having to remove Kana’s memories.

Here’s the thing, the zodiac can’t go against the god. They can’t say “Well Screw you we’re through! I don’t want you in my life anymore,” because of the curse. This means that even if Shigure wanted to hurt Akito by screaming and telling them off for their actions, he can’t. His desire to be loved by the god and love the god trumps every other emotion. This was why Yuki couldn’t run away, this was why Hatori can’t blame Akito for his eye issue. That feeling of love makes it impossible for him to just break it off and walk away. And, again, he’s the dog, so that feeling of betrayal runs so much deeper than say what it would with the snake or the boar.

So what does he do? Hurt the god the only way he knows how; not with words because words won’t hurt the god since Akito has suffered way a lot with words and has grown used to being called all sorts of nasty things, but with actions. And those actions also hurt him as well because while yes they totally cause Akito pain and suffering, and Akito turns around and uses it as a reason to banish him from the compound, it also backfires on him due to the fact that the person he used to hurt Akito can now use what happened as Blackmail on him, and hurt him with what she knows. Because that wretched witch of a woman is a monster, full stop. So yeah, while Shigure doesn’t have the level of Trauma that for example, Yuki has, he still deals with his own trauma that he instilled on himself and also has to deal with the fall out from that. His actions are all for selfish reasons, but selfish reasons to be with the god for his own personal gain and desires. There’s a lot wrong with Shigure, and even his son later says that his dad is a Manipulator in Fruits Basket Another, so he hasn’t changed very much since then. That’s why I think he needs help.

As for what he needs to do, I think getting away fully from Akito and his family would help. He’s a writer so, go do a convention/Book signing circuit. Meet new people, see a therapist to get him out of that damn complex he has. The man may be better off than certain other members of the group, but he’s not the nicest or healthiest one of the bunch. He needs to be around people that can call out his BS more and can’t be played with.

Hope this makes sense.

#fruits basket#fruits basket reboot#fruba#fruba 2019#fruits basket spoilers#fruba spoilers#shigure sohma#akito sohma

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a special guest post by Scott Holleran:

◊

My first experience of this movie was probably on television, probably in fragments. It made an impression but the movie ranged into my memory as a series of scenes disembodied from the whole work. For example, I remember watching the burning of Atlanta and certain, distinctive scenes and not much else. So, my first impressions were perfect for today’s conceptual-deprivation culture. That’s the poverty of being among the TV generation.

It took a long time to appreciate this film as a work of art, which now I know it is. At some point, as I began to take a serious interest in movies, I rediscovered it on home video. Then, again, on disc and possibly again in a revival house on one of those scratchy prints with popping sounds. That a civilization could be gone with the wind came through and I was an admirer. Later, I read about the novel upon which the movie’s based, which, with a romance novel-type jacket design for the mass market paperback edition, was off-putting.

At some point, it dawned on me that Gone With the Wind is an important epic motion picture so I sought its source and read the novel. I was astonished at the brilliant writing. I instantly observed a similarity to my favorite novel, also an epic of American literature and also written by an author who happens to be a woman. Gone With the Wind (1936) by Margaret Mitchell conveys the romanticism, scope and grandeur of Atlas Shrugged (1957) by Ayn Rand and it’s worth noting that Rand’s first novel, too, involved a love triangle woven into the end of an era in her own 1936 novel, We the Living.

After reading Mitchell’s novel, I saw the movie again — and again. Each time, I was more impressed. And, each time, I was more impressed that I was able to be additionally impressed. This is because, as you probably know, the more you know and study a motion picture, the more easily the film can lose its newness, its ability to hold and sustain interest or focus, suspense, tension or sense of plot progression and, as a result, the less likely it can be to stir one’s original passion.

Then, a few weeks ago, I saw Gone With the Wind, which, this year, marks its 80th anniversary in a culture in which it is extremely likely to be impugned or maligned. I saw it for the first time at one of the grandest movie theaters on earth: Sid Grauman’s Chinese theater on Hollywood Boulevard.

And, this time, for the first time, I was moved … to tears.

The nearly four-hour motion picture begins with three characters in Georgia talking about war. This is an essential starting point. The novel more or less begins with this starting point, too. Gone With the Wind frames its story within an argument over the fact of an oncoming war. It’s not that they’re debating the merits of war. They’re discussing the prospect of war as such; they’re considering the impact of war on their lives. So, this, the fundamental choice to face the facts of reality, is the starting point. Not the war itself. Not slavery, the issue in dispute.

Gone With the Wind is not a war movie. Gone With the Wind is not a slavery movie. Any discourse of it as either entirely misses the movie. It is also, strictly speaking, not a romance, though war, slavery and romance factor into its drama to various degrees. Gone With the Wind dramatizes an entire civilization through the life of a single individual.

Her name is Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh at her best).

Shallow, scheming and self-centered, she’s enraged when she learns during this discussion, in which she’s attempting to ignore the reality of impending civil war, that the object of her desire, Ashley Wilkes (Leslie Howard), plans to marry his cousin, Melanie Hamilton (Olivia de Havilland). In subsequent scenes, the men who will become pivotal to the young, impetuous Scarlett’s life, including her father, Gerald O’Hara, but also Frank Kennedy, Ashley Wilkes, Charles Hamilton and a cad named Rhett Butler, argue war on the merits, whistle “Dixie” and, with the recklessness which exemplifies the pre-Civil War American South, crow about going to war.

In this sense, there is real substance to this movie in terms of its grasp of facts and history. Every Southern deficiency is depicted here. The staggeringly affected manners, the pompous preposterousness, the asinine traditions but also the proportionately and wildly irrational inflation of people’s sense of themselves with regard to their actual merit and worth, let alone the source of their wealth, not the main focus and therefore largely unseen. The fact of slave labor is, however, shown, even if it’s not dramatized, though it is more explicit than most films of the era. House, field and overseer are each crucial elements of Twelve Oaks and Tara, the plantations where Gone With the Wind takes place.

What’s good in the South, too, is depicted. The stunning visuals, the land, manners, socializing and courtship and the gentle way of life. Pretty and feisty Scarlett, who’s earned a reputation for being bolder than her peers, holds court and gets talked about by other females and looked upon by men. The outbreak of civil war occurs within her context.

The plot revolves around Scarlett O’Hara; there is a sense in which her pettiness will be tested by war — and what’s impure about Scarlett is fundamentally what will be Gone With the Wind.

The early evidence is Scarlett standing at the window, looking down upon newlyweds Melanie and Ashley. Here’s the heroine on the inside looking out. Yet think about the meaning of her dilemma; she’s really trapped within the Old South, as the opening titles refer to this archaic slave society. In this sense, Scarlett dramatizes how the South’s ways impair the powerful, too. Her only real saviors, friends and comrades, as far as Scarlett knows, are slaves and an angry Irishman. Everyone else is happily, some even stupidly, off to war. In a flash, again like the title, they are gone. Scarlett is left behind — abandoned, lonely and alone.

What comes next builds character, with an outbreak of measles, a move to Atlanta and the entre of the ridiculous Aunt Pittypat, as cartoonish a figure as in the novel. Scarlett’s Mammy (Hattie McDaniel in one of the screen’s greatest performances), knowing all along what exploits the ambitious young missy has in mind, represents the best of Scarlett’s youthful vigor; Mammy fosters, shapes and marks her charge’s growth. Amid a dance, a bid and donation of a ring, Scarlett learns from her new companion, Melanie, wife of the man she thinks she loves.

Here are women in service at war. This, too, is to the film’s credit. Gone With the Wind remains one of the most intelligent, insightful portrayals of women at war ever made, better and more knowing than the hordes of depictions of today’s mindless women on screen who rarely if ever think about anything having to do with serious issues, let alone war or the men sent to fight them.

With intermittent titles, David O. Selznick’s Gone With the Wind, famously directed by Victor Fleming (The Wizard of Oz), with others also filling in, shifts from breeze to gust with news from Gettysburg. Then, come the war-torn faces of those in Atlanta cast down in bonnets amid news of mass death. Fleming lingers on a list of those killed in action. It is words, not pictures that tell the horrid tale. The camera scrolls down, down, down and down on the same three words.

Cue the theme song “Dixie” as a reprise to the earlier tune’s sense of false jubilation and enter a man of reason, Doctor Meade (Harry Davenport), whose role in the picture is a crucial representation of what will become Scarlett’s education. In a shift to black-and-white color schemes from the rest of the film’s vibrant colors, Gone With the Wind goes from sad and mournful “Dixie” to a musically infused projection of a funeral procession in which Johnny comes marching home.

As Pittypat, Meade, Mammy, Melanie and a young slave named Prissy (Butterfly McQueen) besides Scarlett get dragged, plunged and thrust into the South’s mass death and destruction, in comes Rhett Butler (Clark Gable, brilliantly cast and stellar in the role) with vitality, passion and rage — at the Old South for being the Old South. Butler represents the New South, post-slavery, post-Civil War, though it’s never fashioned or made explicit. What a waste of human life — this is the meaning of his every form of his disgust and he makes no attempt to conceal his emotions or suppress himself in expressing what he feels. Like Scarlett, he is a liberated soul stifled and trapped by the way things are.

There’s music, humor and, during a dance which captures and underscores the surrealism of life during wartime, a total breach from traditionalism. Life remains drab as Scarlett and Atlanta face severe deprivation. Butler has a prostitute, Belle Watling (Ona Munson), to help him ease the chronic anxiety, guilt and agony of war and she’s more than a cliché. The pictures show rain, shadows and the hotly feared Union General William Sherman’s shelling of Atlanta, with churches coming on like a holy calling from God to cease and desist with the Old South rebellion. Pictures of Jesus Christ accompany the sound of moans, the sights of a church and, in one of the movies’ most iconic scenes, the camera pulls back for a scene of mass death and dying.

“Peace be within thy walls“ incongruously graces the screen after Scarlett O’Hara encounters a patient with gangrene. Perhaps you don’t know or remember the grit of Gone With the Wind but it’s there. Between marriages, the making of Scarlett from romantic Southern belle to seasoned war bride happens during Atlanta’s silence and siege. And it isn’t even Intermission.

Before that comes, as Rhett Butler finally kisses Scarlett and enlists in the war for a kind of misintegrated sense of honor, slave Prissy hinges the plot. Prissy’s trauma triggers a key reaction that results in the story’s classic and quite penetrating tale within a tale of three women and a baby. Though this famous scene is generally regarded as humorous, I think after seeing Gone With the Wind in the Chinese theater that simple-minded Prissy’s meltdown underscores the folly of slavery even as it echoes as a call and response to Scarlett’s own earlier cluelessness.

A foreshadowing scene on a bridge marks the end of slavery preceding a scene in which women take refuge in reading (in the novel, it’s a story by Victor Hugo; here, it’s fiction by Charles Dickens). The self-made theme continues with a rainbow followed by blackness, fog and a strange yet familiar place.

The shock and violence of post-war Tara soon becomes clear. Scarlett strikes her sister, Prissy and pretty much everyone else except her mother figure, Mammy, and she forges a secret bond with Melanie over the death of a soldier. By the time war widow Scarlett, who’s remade herself as a businesswoman in post-war Southern society, meets again with her true love Ashley Wilkes, who tells her that he admires her for “facing reality“, the heroine grips the earth and grasps her property rights, legacy and life lessons and vows … to herself and her own ego.

Gone With the Wind essentially carries Scarlett in conversation with herself throughout the epic movie. From that first conversation at Tara with her suitors, the Tarleton twins, to becoming a Confederate captain’s wife in New Orleans and hiring as her subordinate the man to whom she’d once pledged to worship and motherhood, Scarlett O’Hara is both intransigent and indomitable. She will not be struck down.

Like Mammy, the former slave woman whose respect everyone respectable seeks to earn and keep, Scarlett keeps company with herself as a worldly woman alone. She makes mistakes — she makes a terrible parent — and she makes money and love. Scarlett liberates herself from tradition for capitalism, egoism and her own way of life. Gone With the Wind traces her journey in this sense from selflessness to selfishness, in time for the man whose love she finally earns to come full circle with his own mistakes, i.e., drinking alone and taking pity on himself, to reject her with the movie’s most famous line.

“Frankly, my dear…” and the precision with which Mr. Gable delivers the line redeems the film’s previous strife and tension into a single moment. It is tempting to root for what at first might seem like his own redemption. But Gone With the Wind is not the leading man’s story and, on the movie’s terns, it’s a mistake to jeer or cheer the line.

‘Frankly’ spends itself on a serious dramatic moment; it signifies Rhett Butler’s ultimate betrayal of himself — in particular, his idealism — and everything he loves. And it signals one of the screen’s greatest victories.

While the ‘Frankly’ line endures in audience memories, it is tellingly uttered only after man and woman stand as equals on the landing of the staircase from which Scarlett has literally taken a tumble in a penultimate descent — only to rise again — and, also tellingly, it comes before the movie’s last and final line.

“I’ll figure out a way to get him back … tomorrow is another day.”

This is the triumph, the meaning and the glory of Gone With the Wind. It is not a film about the slavery. It is not a movie about civil war. It is not a picture of what war does to a slave, a woman and a man — or a family, a home and way of life, though it rarely gets credit for its insights into each of those dramatizations. There is depth to this movie about Prissy, the overseer, Pittypat, India, Charles, Sue Ellen and more, not just Ashley, Melanie, Mammy, Dr. Meade or Scarlett and Rhett Butler.

Like We the Living, Atlas Shrugged and other epic novels by Hugo, Rand and other great works of literature and movies, it is an expression of the ability of the individual to resist the times, the trials and ruins of the day, rise and never let one’s ego be destroyed. It is the story of a man, or, in this case, a woman — or, in any case, a girl who becomes one — and it is certainly not a romance for romance’s sake. Gone With the Wind depicts the promise not to yield, suffer and be beaten down. It is in this sense, to paraphrase one its admirers, Ayn Rand, a paean to forging the “I” one must learn how to say before one can learn to say “I love you”.

This is why it ends where it vows to once again begin.

—

Gone With the Wind screened during the 10th anniversary Turner Classic Movies festival on April 14, 2019 for its historic 80th anniversary at the Chinese movie theater designed and built by Sid Grauman. This was the 25th anniversary date of the film’s initial airing — the first motion picture showcased without interruption or editing — on Ted Turner’s Turner Classic Movies (TCM) cable channel’s first day of launch. The movie was introduced by TCM’s festival director, Genevieve McGuillicuddy, before the original Robert Osborne introduction from April 14, 1994 was shown before the movie.

◊

Scott Holleran began his professional writing career as a newspaper correspondent in 1991. He’s worked in a variety of media, including magazines, broadcasting and Internet ventures. His news, cultural commentary, sports and other topical articles has been published in the Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal and Philadelphia Inquirer. You can find Scott on Facebook, Twitter or on his website. I’m thrilled Scott reached out to feature this entry on Once Upon a Screen. I hope there will be others.

Analysis: GONE WITH THE WIND (1939) This is a special guest post by Scott Holleran: ◊ My first experience of this movie was probably on television, probably in fragments.

#Butterfly McQueen#Clark Gable#David O. Selznick#Gone with the Wind#Harry Davenport#Hattie McDaniel#Leslie Howard#Margaret Mitchell#Olivia de Havilland#Ona Munson#TCM#Victor Fleming#Vivien Leigh

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi...hi! I hope i'm not bothering you, but can i ask your opinion about oboro? I love him so much and i don't get it why some of fans doesn't like him. thank you so much ^^

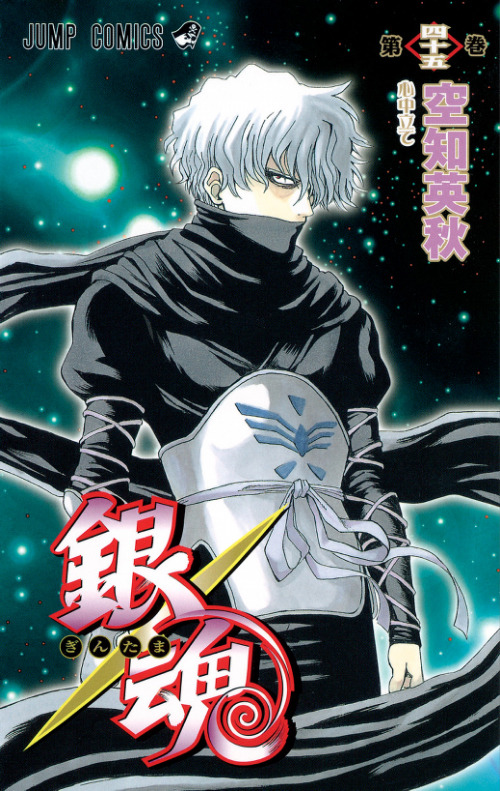

Hi! Don’t worry, you’re not bothering me at all. :) I’m always happy to talk about Gintama in any way. That’s why I made this blog.

Sometimes people don’t like certain characters because they just don’t and we don’t have to like every single character. To me, though, that’s different from those who seem to have a personal vendetta against characters and spend their time hating them and talking about how much they hate them, which makes no sense to me. Why waste time on characters you hate when you can invest that time in the characters you love? There’s a difference between critiquing a character and outright hating on them just to be petty and cause drama.

Anyway, on to Oboro, who I like and don’t hate in the slightest – and this doesn’t mean I seek to justify his actions. People get confused on this to the point where they take start judging people’s moral character just from the characters they like, especially if they are villains. This kind of logic comes from the desire to put everyone on a pedestal, even fictional characters, without realizing that it’s possible to like a character without needing to somehow justify what they’ve done so that you can appear morally superior to others. There are some anime and book villains I like, but it doesn’t mean I’m a terrible person who’d do the same bad deeds. It simply means I like the way they were designed and the role they play in the story. Writing a good villain can be as challenging as writing a good hero or character in general.

Okay, now back to Oboro for real:

(Putting the rest of my answer under a cut for spoilers, so heads up, Anon, if you haven’t read the Rakuyou arc.

Also, to the other Anon before, I will reply to your second message with additional thoughts of mine in several hours’ time. My brain needs rest first. Thank you for your patience.)

Some people don’t like Oboro because he’s done some less than heroic things. There’s no going around this and we don’t need to make excuses for what he’s done. Oboro is the leader of the Naraku, who have been in league with the Tendoshuu, who are not exactly nice people. Focusing on Oboro only, he’s fought and injured Gintoki and put the people he cares about in danger. He played a role in Shouyou’s execution, damaged Takasugi’s eye and more, and has just generally shown up to throw a wrench in the plans of the people we usually root for. Plus, being involved with Shouyou in that way caused a lot of physical pain and psychological trauma for Gintoki, Takasugi, and Katsura…that doesn’t exactly make some fans wave their pom-poms for him.

Oboro seemingly died in the Courtesan of a Nation arc and people thought that was the last we’d see of him. Then, he reappeared in the Shogun Assassination arc, where he also seemingly died and they thought that was it. And then he appeared again in the Farewell Shinsengumi arc and sustained major injuries. And then so on to the Rakuyou arc. This man just wouldn’t stay dead or immobilized, and that probably annoyed people, especially when he kept trying to kill Gintoki and others.

As for myself, I liked Oboro before I knew of his back story. I think he’s an interesting antagonist and one of my favourites in the series. One reason is because he’s voiced by Inoue Kazuhiko, who is one of my favourite voice actors. I think Oboro has a cool character design and stellar combat skills. I like that he’s rather stoic and isn’t figuratively twirling his moustache with evil glee like others. He stays calm and composed for the most part, except for when he becomes enraged.

(Doesn’t he look so cool? I had to include this pic.)

I also like that he’s one of the people who can give Gintoki a hard time in battle. Now, that doesn’t mean I like when people harm Gintoki, but if he were all-powerful and constantly defeating people without any challenge at all, it would be boring and predictable. The Gintoki vs. Oboro fight is memorable for the fact that Oboro was a tough opponent who brought back unwanted war memories.

Oboro shares many parallels with Gintoki. Besides physical appearance, they owe their lives to the same man: Yoshida Shouyou. Very much like Gintoki, Oboro tagged along with Shouyou, unwilling to leave him, feeling indebted to him for saving his life. Oboro has a rather low opinion of himself, as shown in the flashbacks of the Rakuyou arc: he didn’t believe himself to be anyone special or of importance to others. An orphan bought and sold by bandits, Oboro didn’t expect anything more and knew nothing more than pain, fear, and emptiness with no purpose in life except to serve others as an object, not a human being. And that makes my heart ache.

He’s not on a quest for ultimate power or to destroy the world for the heck of it. All of that is the result of his loyalty to Shouyou/Utsuro; he’ll do whatever it takes to “remove obstacles in that man’s way,” and if it means the downfall of a nation or killing Shouyou’s other students, so be it. Even years later, he only sees himself as a vessel to be used, a servant to Utsuro, forevermore.

Oboro was willing to do anything for Shouyou, prepared to become even an assassin. He was ready to become the first disciple of Shouyou’s and start a new life with him. And when the Naraku assassins came looking for them, Oboro sacrificed himself just so that Shouyou could escape and make his dream of opening up Shouka Sonjuku a reality. Oboro knew Shouyou no longer wanted to kill, and wanted his teacher and saviour to achieve all that because Oboro loved Shouyou more than his own life. Shouyou made Oboro feel human.

That kind of dedication speaks volumes of Oboro’s character. But, of course, Oboro survived, the Naraku made him one of their own, and he decided to rise up in the ranks – all to protect Utsuro, even if he could no longer be with him. Everything was and is for Utsuro/Shouyou. Everything.

Then, Oboro saw Shouyou with Gintoki, Katsura, and Takasugi. He must’ve been relieved and glad that Shouyou was able to accomplish his dream and give new life to other children…but I can only imagine the deep sorrow Oboro must’ve felt, because he could not be with them, that he was apparently forgotten by the man he was so devoted to. Hearing him express his wish, that he “would have liked to become one of them,” as his dying words…it really breaks my heart because I bet he would have been such a good older brother figure to Gintoki, Takasugi, and Katsura in another world and time.

That deep sorrow turned into something else, and Oboro pulled strings to have Utsuro arrested and then executed. “To get my master, I killed my master” – twisted, to say the least, and yet fascinating. Shouyou returned, but not as the man Oboro once knew: Utsuro. But that didn’t matter – it’s something Oboro points out to Takasugi, the key difference between them. Shouyou, Utsuro, the name doesn’t matter, because he is one and the same to Oboro.

But after his “blood vow” was fulfilled and he was about to die, Oboro told Takasugi and all of Shouyou’s disciples, consequently, the truth about Shouyou/Utsuro. Even at the end, Oboro wanted Shouyou to be free again, free from his immortality that causes him so much suffering. He knows Shouyou’s other students – most especially Gintoki – will be the ones to bring an end to that. He was probably envious of their closeness with Shouyou, that they got to spend more time with Shouyou than he did, but still, he shared vital information to help them, even after he had tried to kill them. Then, as I stated here, I believe Oboro dying at Takasugi’s hands for good was a fitting end for him.

And that’s why I love Oboro. He’s a complicated man and a memorable antagonist. His devotion to Shouyou led him down a twisted and tragic path, but I’m sure he would have preferred it to a life of nothingness without Shouyou.

I can understand why people might dislike him, but I will always be fond of him.

21 notes

·

View notes