#will you push back against the idea that union actors having required break times is entitled?

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The lack of regard for actors in general when it comes to labor rights within the arts is galling, actually.

#like I'll see ppl (rightly) arguing that illustrators and artists deserve fair compensation for labor#and then make fun of actors for honing their craft bc they do it weird and sometimes Shitty People are actors#and there's always this conflation of actors as a whole with a relative handful of big screen actors#which means no one is bringing up the open exploitation and sabotage of actors on broadway rn by producers#and the flagrant complicity of AEA in this mistreatment#like 'ooo somethings wring with ur industry u coukdnt even sell a kpop show'#ok so will u support actors trying to get financial transparency?#will you fight to ensure that if a show closes within 2 months of opening actors still get paid enough to fucking survive?#will you fight to hold AEA accountable#and/or will you support actors shoukd they form a new union#will you push back against the idea that union actors having required break times is entitled?#like yeah theres an industry problem but youre only bringing it up to point out haha kpop musical failed#this has been ongoing for years at this point#this burying of shows#ppl live in nyc and dont know whats on bway#a 4 month run is one of the longest slated currentlu#do u have any idea what this means for actors#like#just#ugh

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It's Friday night.

You've locked yourself out.

The streets are empty.

> RETRACE STEPS

(I finished an MS Paint fan adventure.)

Creator’s Commentary

Normally, when I post stories on this blog, I throw the whole thing beneath the spoiler break - but that’s not really possible this time around. Click the link above if you haven’t read it yet - it only takes about ten minutes - then come back here if you want.

All done? Still with me? Okay, cool, because we’re going to be heading into spoiler territory here pretty quickly.

“RETRACE STEPS”

OPEN ON BLACK:

INT. – LATE AFTERNOON

A door opens on the right, spilling light into the threshold. The ceiling light automatically flickers on. Alice enters frame and heads to her door.

She tries the handle, but the door doesn’t budge. As her hand depresses the handle, the title briefly becomes visible.

We return to the original angle. Alice reaches into her left pocket, and finds nothing. She turns to lean against the door, facing the camera, and checks her right pocket, then the pockets of her hoodie. She tries the handle again, but the door is definitely locked. She leans, for a second, motionless.

ALICE Fuck.

She stalks out of the threshold, and the door closes behind her.

I. Making friends is harder than I thought.

When you’re a kid, people sorta make friends for you. Maybe your parents’ friends have kids, so suddenly those kids are your friends. Maybe you go to nursery or school, and then your classmates are kinda your friends too. At least some of those people will probably never stop being your friends. As you move through the education system, that cohort diffuses through the local schools - but chances are a few of your friends will stick with you all the way.

When you arrive at university, chances are you’re completely alone.

You’re thrown through the gauntlet of fresher’s week, forced to put yourself out there as you identify new friends and foes. One of the main attractions of university-managed accommodation - particularly catered accommodation - is that it places you with a huge amount of new people. Heck, part of the idea behind having a roommate is that they’re your “designated friend”.

(I didn’t have a roommate, and ended up going to university with two of my school friends, so these are less experiences and more observations - but that’s not to say I didn’t go out of my way to make new friends in those first weeks.)

After a month or so of the dreaded “three questions” (”What’s your name? Where are you from? What are you studying?”), the cliques have mostly solidified. The college relationships have crumbled, after one or both parties realised they were mostly in it for the sex. The cool people have long since stopped showing up to lectures. You haven’t gone back to any of the sports clubs and societies you signed up for. Maybe, just maybe, you’re occasionally glancing at your phone and wondering if you should finally give your parents a call to let them know you haven’t died.

If you’re lucky, you’ve met your new best friends. If you’re unlucky, then you’re very, very alone.

But of course, it’s not all down to luck.

She stalks out of the threshold, and the door closes behind her. Outside the threshold, there is a shot from the banister above of Alice walking down the stairs, facing away from the camera and typing on her phone.

Outside, Alice sits on the wall and stares at her phone. There is a brief montage of her slowly pacing up and down the path, leaning out into the road to check if anyone’s coming, checking her phone, peering into the downstairs window, kicking loose stones back into the gravel, and back to her sitting on the wall. After a few seconds, she puts her phone away and trudges out of frame across the stones.

II. Coming up with stories is harder than I thought.

I can’t exactly remember what I put my name down for during freshers’ week, but one way or another I ended up dragging a new friend to a writing workshop for my university’s filmmaking society. A bunch of strangers from all years were crammed around some tables that had been pushed together in our Student Union’s bar.

This guy, the head of the- president of the society? Sure, the President, let’s go with that. The President stands up and sorta fumbles his way through an introduction, before telling us to turn to the person next to us. I turn to my friend, because I don’t like talking to strangers. Then the President tells us (I might be misremembering here) that we’ve got one minute to come up with a story.

There’s a moment of awkward silence, because nobody wants to be the first person to start talking about the first dumb idea that’s popped into their head at those words.

Then the conversations start.

I went into that first minute expecting to come up with absolutely nothing. To be honest, I’m pretty sure we came up with nothing. I think there might’ve been some implication that they’d go around the table once time was up asking for quick summaries - this terrified me not just at the prospect of having to bluff my way through a pitch, but at the prospect of having to listen to everyone else do the same. Honestly, the moment that’s stuck in my mind most since was when I talked to the guy sitting on the other side of me, and he started trying to tell me about Lord of the Rings, which... okay, I don’t like Lord of the Rings, sue me, whatever. Someone else talked about the Batman movies at one point, and - actually, that might’ve been the same guy. Y’know what, I’ve gotten off track.

The point is that at some point during that meeting, Retrace Steps was born. I don’t remember when exactly, or how I came up with it - I suspect I’d locked myself out of accommodation at some point, or knew a friend who had, and thought it’d be funny to do a story where someone does that and can’t for the life of them get back in. In order to add complications, I decided that their roommate wouldn’t answer their texts, and that the residence office would be out of hours - and that was when the idea that everyone had disappeared came into my head.

INT. MAIN BUILDING – LATE AFTERNOON

Over-the-shoulder shot of Alice entering a corridor in the main building. The camera focuses on the sign saying ‘ON DUTY’, then pans across to the door to the general office. It focuses on another sign saying ‘The office is now closed...’, then across to another sign by the door with a phone number on it.

Foreground with Alice comes back into focus. She takes out her phone and dials.

ALICE Hello? I’ve locked myself out, do you have a spare...

She trails off, and puts the phone away. Clearly, someone’s answered but has hung up. Cut across for a close-up of her face, trying to figure out her next move.

SERIES OF BRIEF SHOTS:

Alice looks for her keys in:

A) a computer lab B) a library C) a laundry room D) a games room E) a bathroom

There are no keys, and no people. Alice goes to the kitchen and gets a mini-doughnut out from a box in a cupboard. She eats it thoughtfully. Once she’s finished, she reaches out to grab another, hesitates, and decides against it.

III. Making movies is harder than I thought.

A lot of the ideas being thrown around the table were for some pretty high-concept stuff, and I remember thinking - hang on, aren’t you supposed to actually be filming that? I’d approached the challenge from the angle of “what do I have, and what can I make with it”, not “what do I want to make, and how can I make it”. In an unfortunate twist of fate, my film - of all those that were conceived that day - would end up being far and away the worst. But I’ll get to that.

For a student film, the "everybody disappears and you’re locked out” concept made perfect sense - you could film it at your accommodation, you’d only need a single actor, and it’s a story that your audience will probably (if not immediately, then at least after another month or two) be able to relate to.

(Side note: I obviously hadn’t come up with this concept whole-cloth. Michael Grant’s Gone series of YA novels - which I’d finished reading midway through secondary school - is a superhero story about a bunch of kids on an island where all the adults have suddenly disappeared. More pertinently, Starscribe’s The Last Pony on Earth is the diary of someone who wakes up completely alone in their city, only in the body of a cartoon horse. Yes, Retrace Steps has its roots in My Little Pony fanfiction, and I’m very sorry about that.)

My friend wasn’t interested in sticking with the society - he mostly did it to back me up - but I guess I was. Knowing that most people would be angling for directorial roles, I signed up as a writer and threw together a script. An email came back the following day; apparently from el Presidente himself:

Thank you for sending the script Retrace Steps. As you have said in your original email, the script is quite short. But I do think it is a very intriguing concept nonetheless, one that is probably helped more so than hampered by its brevity. After all, the nature of your script would to a degree require an empty street, as well as a quiet hall, both of which are rare commodities indeed, especially during the weekends.

Anyways, since the script is well formatted, I will just offer a suggestion, one which I hope may help your final edit before the deadline, should you wish to do so.

Your script portrays excellently Sam's anxiety over the course of the narrative, from his inability to find his keys, then his inability to find anyone at all. I do however believe that you could make the final scene perhaps have more impact. How this is done depends on the overarching theme of the story you are telling, as what you would emphasize at the films' conclusion would depend on it.

Is it an allegory to the anxieties of the average student (Sam), who finds himself socially isolated by a sense of exile or ignorance of the larger community? Or is it perhaps more of an absurdist comedy, or even horror? Though I could wrong, I was under the impression that it was more likely to be the former than the latter. If so, could the story end with it emphasizing Sam's exclusion from society, such as a close up shot to the door and keyhole?

As with all feedback, you are under no obligation to take them to heart, and the things I pointed out are but small things to consider on an otherwise great piece of work. Thank you for making this piece available to the rest of the society.

It seemed that I’d successfully communicated the theme of isolation - less so the theme of entitlement. Bringing that theme to the fore would be my biggest challenge throughout subsequent drafts of the script (where I failed miserably) and the development of the fanventure (on which the jury’s still out).

(Those subsequent drafts would also see the characters “Sam” and “Chris” - those being the names of two friends I’d pegged as backup actors for the roles - get renamed as a more generic “Alice” and “Bob”.)

The Retrace Steps team consisted of a director, a producer, a cameraman/editor, and me. I met with the director only a couple of times - she seemed pretty competent, but decided that she couldn’t commit the time to the project and stepped down. Our producer was all too happy to take over the role.

Auditions started shortly after the teams were assigned - although I’d used male pronouns in the script, I’d anticipated that there’d be a greater demand for male actors (because most of the writers/directors would be male and most of the actors would be female) and planned to go into the auditions with no preference one way or another.

In truth, however, I think the gender of the story’s lead does have a noticeable impact on how it comes across - at least in film, where there’s no good means of narration. Speaking very broadly, when dealing with themes of isolation, I think the key question that comes to an audience’s mind is “why is this person isolated?” - and if the character is male, I feel like they’re more likely to assume the answer is a personal failure of some sort; there must surely be something wrong with him. If you’re reading this, chances are you’re in pretty deep on the internet, where I think these issues of perception are less pronounced - so if your instinct is to buck against those assumptions, well, I’m glad.

(The fanventure would end up using second-person narration, they/them pronouns and androgynous character designs to sidestep these issues entirely, while drawing the reader directly into the conflict.)

Our producer/director wasn’t able to make the callbacks (which felt like another red flag), so it was down to me to relay back to her what I thought of everyone. It was kind of a challenging process, because - as I’ve said - I don’t like talking to strangers and I certainly don’t like telling them what to do. Still, I was able to more-or-less settle into it, and eventually the director and I settled on a girl who seemed to know what she was doing. I feel a little bad for effectively putting her through the project, but the joke’s on us: within a year she’d been elected el Presidente of the entire students’ association. I can only assume that none of her opponents knew about the movie; it might’ve made for a pretty good smear campaign. Or not, nobody really cares about student politics anyway.

(The director couldn’t make it to the meeting where the society allocated the actors either. Basically, the President went through the actors one by one, and the teams would negotiate for each of them in turn. I’m fairly sure only one or two of the other teams were after the same actress as we were - I basically just said “we only need one cast member and we thought she’d do best,” and that was all it took; once that was settled I simply left and pretty much didn’t interact with any other members of the society in person until the screening. The other roles she could’ve got were minor anyway - although, in retrospect, she might’ve been better off.)

I think I’m not going to bother explaining exactly why the Retrace Steps short film turned out to be such a disaster. I’m pretty willing to pin the blame at the director’s feet - she’d arrange shoots at strange times with little notice, only to show up half an hour late herself. When she and I disagreed on part of the story, our cinematographer generally sided with her; she had the strongest personality of any of us, while I didn’t want to cause trouble. Our other team members - the actress and a lights guy who the society’d lumped with us (the lights ended up being a collaborative effort) - stayed out of it.

As the end of the semester approached, we were missing crucial swathes of footage. Our director pulled an ending out of her ass - a brief confrontation between myself-as-Bob and the actress, that... somehow involved custard creams? The script called for doughnuts, but we weren’t organised enough to have bought those in advance, and the biscuits were all we had at hand. I can’t actually remember exactly how it went, because it didn’t make any sense, but I remember enough to know that it actually ended up indirectly inspiring the execution of the revised ending present in the fanventure.

The end of the semester arrived. The society had hired out the small hall in the students’ union to screen all the movies. The screening started, and there was no sign of our director or cinematographer - they’d apparently been editing all afternoon. Eventually they arrived and sat down near myself and our actress.

I’m not gonna lie. What followed wasn’t the most embarrassing experience of my life. It probably wasn’t even in the top ten. But it was pretty embarrassing. All the movies were pretty awful in their own ways, but ours was uniquely terrible. To our director’s credit, she’d managed to cut the footage together into something we could maybe pass off as an absurdist comedy (which, to my own credit, had been kinda what I’d pictured in the first place - I’d just pictured something with a little more in the way of actual narrative). Even so, despite the awkward laughs - or perhaps because of them - it was atrocious.

I’ve only seen the movie once, at that screening, and I cringed the whole way through. Some time later, the director messaged me asking if I had a copy - apparently it hadn’t occurred to her to save one for herself, and our ex-cinematographer had gone AWOL - but I didn’t. Stupidly, I’d decided not to chase after one either, because in the moment I couldn’t imagine wanting to put myself through the experience of seeing it again. Almost half a year later, when I was almost done with the fanventure, I got back in touch with both the director and the society: I wanted to have the movie on hand so I could write about it in this commentary, but I didn’t say that, because I didn’t want to let on that I’d remade it as a frikkin’ webcomic. The person from the society said she knew someone who had a copy, and that she’d ask, but she never got back to me and by the time I remembered to chase her up it felt like it was too late to actually do so. It’s likely that the movie will never resurface - which I guess is good in a way, in that there’s no way in hell I’m gonna show it to any of you.

I was bitter. I wanted nothing to do with student societies. I wanted nothing to do with filmmaking, and haven’t made a film since - not unless you count Are You Happy, which I pretty much only made because I could do so entirely on my own. I’m much more leery about the prospect of collaborating with strangers, although I suspect that if an opportunity came my way I’d probably take it.

(Side note: last October, in an interaction which wound up being pretty excruciating in its own right, I contributed a satirical listicle to another society. This was a nightmare for a variety of reasons, but - suffice to say - it’s not particularly pleasant to discover that somebody’s made a bunch of edits to your work without telling you, especially if the changes are for the worse. I wish I had more positive things to say about collaboration, really, I do. Actually, I will say that my experiences working with others in the Transformers fandom have been pretty darn good - you can find details of that stuff over on the list of things I made.)

For a good while, I suspected that Retrace Steps would never see the light of day. I entertained the idea of rounding up a few of my friends and bashing the thing out myself over the course of a few weekends, but I ended up being pretty busy with other stuff. Besides, the society had the nice lights and cameras, and I didn’t want to go through the hassle of borrowing from them. Most of all, there was the tiny voice telling me that my script probably hadn’t ever been much good in the first place, and that I should switch back to pure prose - a medium with a much faster turnaround.

(That voice was right, as I’m sure you’re seeing for yourself. Look, it was a student film, there’s probably no such thing as a good student film - I’m just banking on fanventure-adaptation-of-a-bad-student-film still being fair game.)

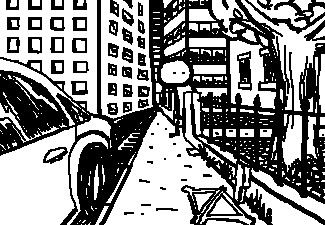

EXT. STREET

Wide shot of Alice walking through the street, shouting. It is raining.

ALICE Hello? Is anybody there?

Overhead shot as she looks up and squints at the sky, then reaches back and lifts her hood.

Everything slows down. Cut to a side-on shot of Alice lifting her hood. A muted sound slowly turns into the jangle of keys as things speed up again. Cut across to medium shot face-on, as Alice looks confused. She reaches up with her other hand into her raised hood, and pulls out the keys. She holds them between two fingers, and the camera focuses on them.

ALICE Oh, for fuck’s sake.

IV. Talking about Retrace Steps without talking a little bit about Homestuck is harder than I thought.

Homestuck was this big multimedia webcomic that ran from 2009 to 2016. Homestuck was very good, and its unique “MS Paint Adventures” format inspired thousands of “MS Paint Fan Adventures” - some of which take Homestuck’s premise, but many of which are otherwise entirely original stories.

The oldest writing on this blog, in fact - presuming I haven’t hidden it out of mortification - is a rudimentary (and really god-awful) fanventure called You’ve Just Been FiRED. Don’t read it, it’s very, very bad, and I abandoned it after about thirty pages - some of which remain unpublished as of writing.

My second attempt at a fanventure, which - no joke - I wrote in the pages of my school planner during one exam season, is called SP00KY M4N0R; unlike traditional fanventures, which use the aesthetic of interactive fiction but none of the non-linear storytelling, this one was a fully-fledged choose-your-own-adventure story. In the following year’s planner, I started writing a spiritual successor called W1LT1NG (the setting of this one is slightly less self-evident: it took place inside an Egyptian pyramid). Neither of these stories have seen the light of day outside of a couple of my friends (and teachers) - but they might, so I’ll discuss them no further.

At some point in high school, I tried adapting SP00KY M4N0R for the web - first in MS Paint, then later in Photoshop CS2 - but put the project on the back burner and never really picked it back up again.

It wasn’t until after I joined the Homestuck Discord server that my interest in fanventures was rekindled. I became its 9615th member on the 6th of January, 2018 - in other words, a good while after we’d wrapped on Retrace Steps - but very quickly realised that its rate of activity was far to high for me to keep up with anything, duly muted it, and pretty much just forgot about it entirely.

Months later, something - presumably in either the Worth the Candle server or the Worm server - drew me back, and I found myself lurking there infrequently. On the 2nd of November, I briefly waded in - to ask some questions about Cordyceps - and after that, I think I lurked on-and-off for pretty much a whole month while I finished the remaining works on Makin’s List of Shills (if you’re wondering what all of these names in italics are, you might want to click that link). After that, I was pretty much there to stay.

A small but notable number of the server’s regulars ran fanventures of their own, and so I found myself becoming much more aware of the format than I ever had been while working on SP00KY M4N0R. Eventually, I decided I wanted to make something of my own - this was shortly after I’d finished working on Another Son, which had ended up being something of a mixed bag in a lot of ways - and hit upon the idea of adapting Retrace Steps as a fanventure.

You see, the thing about fanventures is that many of them begin with the same premise - “you are mysteriously alone”, and then things escalate as you learn more about the world the second-person protagonist has found themselves in. Retrace Steps has that same premise, with a very simple twist - the reason you are mysteriously alone is simply that nobody likes you.

SERIES OF SHOTS:

A) Alice re-enters the building B) She heads up the stairs, C) reaches the door to the threshold D) (a brief return to the original angle from the very beginning of the film) and enters the threshold. E) Extreme close-up of the key entering the lock. F) Over-the-shoulder shot as the door is unlocked and starts to open. G) (180-degree cut) She stares, dumbfounded at what she finds within. F) (Her POV) Her room is full of people, all holding red plastic cups and staring at her.

V. Drawing is harder than I thought.

Before I get into the meat of the work, I should probably give a broad overview of the process I used for creating the images - which, for the most part, was identical to the process I’d used for SP00KY M4N0R. The panels in Homestuck are 650px by 450px; in order to create a rougher (read: more forgiving) look, I halved these dimensions to 325px by 225px. I’d originally planned to scale the images back up to full size during publication, but ended up deciding that the negative space around the smaller frames helped create an atmosphere of isolation. Besides, I wasn’t sure if it’d be possible to scale the images back up without any anti-aliasing.

If you don’t know what anti-aliasing is, I’ll briefly explain - it’s when pixels at the edge of shapes in digital images get changed to a slightly different colour, to create smoother outlines. This works well at high resolutions, but at lower resolutions muddies detail and makes the image appear somewhat blurred - the effect is particularly pronounced if the images are entirely black and white. Homestuck avoids anti-aliasing pretty consistently, and doing so is a hallmark of the MSPA style.

Thankfully, Photoshop CS2 allows you to turn off antialiasing on pretty much every individual tool. I drew all the graphics using a 4px brush, but thanks to a beat-up old variable-pressure graphics tablet I could reduce this to 2px as needed. The 2px brush size was employed pretty heavily for detail in some of the busier environments, and at times I found myself using the selection tool to nudge stuff around at a pixel-by-pixel level.

Although Retrace Steps is adapted from a script, I’m pretty sure none of the dialogue from that script ended up making the jump into the second-person narration of the story. In fact, very few of the script’s locations remain either. The words and the artwork developed in tandem - I was rarely more than a few panels ahead in the script, and would generally let the physical on-panel action inform what was being written.

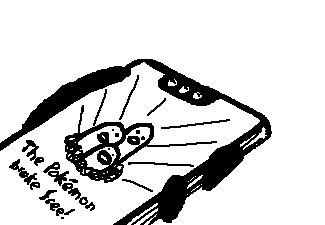

I occasionally looked up bits of reference - most notably to get some architectural details for the Tesco store - but otherwise winged it. Occasionally, in the more complicated images, I’d start out by drawing some perspective lines. For a couple of the images in the credits (specifically the cup and the Poké Ball) I went so far as to use autoshapes as guides, because I was struggling to draw passable circles freehand.

(No, those shapes on the right aren’t my attempts at circles, they’re the guide I used while drawing the doughnut.)

I’ll give more specific thoughts later, but broadly speaking I think my drawings suited the story I was trying to tell about as well as they could. I’m not an artist, and in the future I’m going to stray away from visual projects like this; the part I value most is the writing process, and I’d say that only a tiny fraction of the time I devoted to this project was actually spent writing. The flip side of that, of course, is that people generally much prefer stories with a visual aspect - it’s hard to convince them to read a webcomic, much less a prose story.

ALICE What the actual fuck are you all doing in my room? BOB (somewhat passively) Uhhh… didn’t you get my email? ALICE What email? Everyone in the room stares at her. Then, as one, they move to push her out of the room and shut the door. She protests, until-

ALICE This is my room!

BOB (poking his head back into shot with mucho sass) Yeah, but it’s not though, is it? He slams the door the rest of the way shut, and the lock clicks back into place.

Back to very first angle.

ALICE (quietly, to herself) What the actual fuck.

She knocks on the door loudly.

ALICE (shouting, her face inches from the door) This is my room!

Silence. She tilts her head forward, hitting the door with a sad thud. Then she turns and sits down, back to the door, and the camera cuts to join her at this new level.

She sits for a few seconds, thinking, then gets up again and leaves frame.

VI. Writing this commentary is harder than I thought.

Anyway, I figure the best way to get down into the details is to just start at the beginning and work my way through.

The first twenty panels take place in something of a liminal space - the corridor on which the reader’s room lies. I made sure never to show any of the other doors in the corridor; so far as the reader is concerned, they may as well not exist. The door is numbered “41″ - this being a truncation of “413″, the most ubiquitous of Homestuck’s so-called “meme numbers”. I kinda envisioned the room as being the first on the fourth floor of the building.

(If I’m feeling cheeky, I’ll say that the other doors are the ones up in the site’s navigation bar - they literally exist outside the scope of the panels.)

I probably didn’t spend as much time as I should’ve perfecting this environment - the door’s very wobbly. My first attempt placed it at the end of the corridor, but I didn’t like the way that looked at all.

Just in terms of the site itself, there’s a couple of things to take note of. The first is the solo cup sitting at the top of page, next to the advertisement, which is also the story’s icon on the site - and its only splash of colour (well, except in the ads, which I don’t have any control over). The second is that the link to the next panel is “->” - a slight variation on the command used by Homestuck, which was “==>”. The significance of this should be obvious to Homestuck readers, but I’ll comment no further on either of these details until later.

(Fun fact: I didn’t find out that those big red American plastic party cups had an actual proper name, and that that name was frikkin’ solo cup, until well into the fanventure’s development, if not after I’d finished it entirely. One of my friends used the term in passing conversation - I can’t remember what about, because I was too busy freaking out internally. It’s like pottery; it rhymes.)

On panel 3 - once they’ve walked into the corridor - the lights have turned on, and the entire colour scheme for the comic flips. The idea of having automatic lights was present in the original script, but it wasn’t until pretty late in the fanventure’s development that I decided to make them plot-relevant!

Out of all the images, it’s the close-up of the door on panels 5-7 that comes closest to matching a shot description in the script. The original idea was that the door being locked was the inciting incident that would lead the protagonist to go look for their keys - so the title/command “RETRACE STEPS” would literally appear as they pressed the handle. In the first draft of that panel, this was in fact the case - but my prereaders didn’t think it looked that great, and I was inclined to agree; besides, the title also appeared prominently on the title page and during the credits.

It’s not until panel 7 that we get any words at all - a simple “huh”. In the original script, I made relatively heavy use of profanity in Alice’s dialogue - this was supposed to signify hostility. I wasn’t happy with how this came across, and completely backpedalled in the fanventure - the second-person narration is entirely devoid of swears. I wanted to portray your inability to curse to as a deficiency: you’re unable to fully express yourself. Like most aspects of your character, this isn’t something you’re supposed to consciously notice or understand until after the story’s twist is revealed.

Panel 8 includes a command: “Try door again.” Generally speaking, the commands used in Retrace Steps are much more perfunctory than those in Homestuck - they’re almost entirely devoid of snark, with many being only a single word.

This entire sequence has a lot of legwork to do in terms of laying out the situation in a believable manner without giving too much away. On panel 14, the narration lists your inventory: a phone, a packet of tissues, and a wallet. The phone and the wallet both play direct roles in the narrative, but I consciously chose to include the tissues because I think the word itself has connotations with illness, sadness, and loneliness.

It’s worth noting that these items are those that I personally carry about in real life. Other than the abstract geography of the corridor, this is perhaps the clearest example of me drawing directly from my own day-to-day experiences. The word “self-insert” is kind of a dirty word in a lot of ways, but the truth is that I wanted the protagonist of Retrace Steps to serve as both a self-insert and an audience surrogate. This is why I felt like the MSPA format would serve the story well.

(None of that is to say that you should draw conclusions about me as a person based on the behaviour of the character in the story. Superficially, they share a lot of my tics, but their actual thought processes and motivations are different in many ways.)

Panels 17-19 are just repeated images of the empty corridor; the lights turn off on panel 20, and the site’s colours briefly flip again. Heading into this project, I had the rough idea that I wanted to tell the story in a “nice” number of pages - maybe a hundred, maybe less, maybe more. I decided that, if I repeated the door image, I’d have a buffer to use to shorten or lengthen the final page count as needed - but that turned out not to be necessary. This little span establishes that the lights in the corridor are on a timer, a fact which turns out to be relevant down the line.

The first scene change occurs on panel 21, which shows a stairwell. My original version of this sequence confused basically everyone who saw it - I’d envisioned the camera as being at the bottom, looking up, but everyone presumed I’d done it from the top down. The current approach makes much more sense, as all of the lines of action in the image point towards its centre.

As you descend the stairs and thinks about your roommate, the narration rambles much more. In this story, I decided that use of the internet would be a signifier for loneliness in some way - the roommate has an old-fashioned phone and communicates only by text. I wanted to give the impression that they’re bad at checking their messages; preferring instead just to talk to people face-to-face. That’s not the whole story, though - to a certain extent, they actively ghost you.

Once more, I’m drawing pretty heavily from my own life experiences for this sequence. For a long time in high school, I used to have a terrible flip phone - my parents didn’t want me to have anything better. I eventually upgraded to a terrible smartphone, which I mostly used to play Hill Climb Racing and Glow Hockey. Late in high school, I wound up using a bulky Kindle Fire as a portable computer, with my brother’s old terrible smartphone in case I needed to call anyone; the phone was pretty much always out of battery. It was only within the last six months - halfway through my second year of university - that I got an actual honest-to-god good smartphone. This stuff becomes relevant again later, during the Pokémon GO sequences.

(As I said earlier, I didn’t have a roommate, but my neighbour did - his roommate kept strange hours, and I’m pretty sure most nights he didn’t come back to accommodation to sleep. They got along, but there was an arrangement in place there.)

The image of seeing someone at meals but never speaking to them struck me as a fairly strong one - in student accommodation, you’re forced to interact with people because you use the same amenities, but the extent to which you actually communicate with those people is a matter of personal choice. The narration uses the word “sit”, which I think implies a lack of understanding of that element of choice - you don’t sit together, therefore you cannot speak. The idea that you totally could sit together just doesn’t occur to you.

Anyway, panels 25-33 take place immediately outside the building. With public buildings like this, people who smoke are unlikely to stray far from the door - and the smell lingers for a while after they’re finished. Public smoking has always been one of my pet hates - I’m asthmatic - but I consider the extent to which it bothers me to be something of a character flaw. The protagonist of Retrace Steps is kinda built of flaws like this: things which sound reasonable but are rooted in their lack of empathy.

The narration uses the word “ramble” to describe the text sent to your roommate - later on, we learn that the word “rant” might’ve been more accurate.

This is the point where the story itself notes that it’s a Friday night - a fact which was previously stated in the very first line of its description. The idea of not doing anything on a Friday night is a pretty common symbol for loneliness; it’s the night when most people go out with friends, at the conclusion of the workweek. Tropes are tools - if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

The other symbol for loneliness in this sequence is slightly less obvious, I think - it’s when the reader kicks a single stone out onto the path. The narration notes that they “don’t know” why they did that; this was intended to mirror the story’s central mystery. In the original version, they kicked the stone from the path back in amongst the rest - the idea being that they’d kinda fallen by the wayside, and wanted not to be alone. I kinda go back and forth on which version I prefer, but they get the same thing across.

Panels 34-35 are each “unique” images, in that they only recur in the credits. It felt like a waste to spend a long time drawing complicated images like this without reusing them in any capacity, but I’m glad I did.

The first of these unique images was supposed to convey the city’s emptiness in a clear way. It’s probably one of my favourites, even if it’s pretty rough in places. The forced perspective is more strongly felt in this image than in any other in the fanventure, and it led me to mess up the scale of the protagonist - this was something that I only fixed after the comic was otherwise pretty much done.

I was on the fence as to whether or not to include the billboard. A lot of the imagery in the fanventure is very on-the-nose, but the billboard is easily the most blatant in this respect - the protagonist completely ignores the concept of self-improvement so they can play Pokémon GO. I ended up showing the panel to an uncredited friend, and they convinced me it was a good idea to keep it in.

The Pokémon GO stuff is pretty much when the fanventure jumps the shark, to be honest. You can tell, because the command - “Pokemon GO on your phone” - is a reference to a dumb thing Hillary Clinton said during the 2016 American presidential election.

See, the thing is, the vast majority of the game’s mechanics are designed to encourage going outside and interacting with others - you can ignore or circumvent this, but it’ll cost you one way or another. Which is fascinating to me! The game is easiest if you go out of your way to make friends with other people who play the game. This is a common theme throughout much of Nintendo’s output - and it somehow usually feels less cynical than the kinds of forced interaction you find in many other mobile games.

The bit that’s really fascinating, however, is the lengths people go to avoid these inconveniences. They’ll buy both versions of each new Pokémon game, rather than trading with someone who has the version they didn’t buy! They’ll buy a second Nintendo DS, just so they can get the Pokémon from one game to another! I can’t begrudge them, because I’ve certainly done similar things myself in the past, but I think you can certainly frame it in a way where it looks like all these gamers treat social interaction as an obstacle to overcome. Who’d’ve thought?

The narration on panel 37 ended up going through several revisions, thanks to feedback from Gitaxian. Back when I was new to the Homestuck Discord, Gitaxian was one of the people who made me feel welcome - we both really like this one obscure essay about the live-action Transformers movies (and totally recommend that you should read it). He responded pretty positively to Everything Is Red Now, a Spider-Man comic I made over a year ago, and was my first choice for a prereader on Retrace Steps.

Gitaxian found the sequence in its original form to be a little over-detailed, and suggested that I change its tone from “explaining the game” to “complaining about the game”. He also noted that making it “rantier” would be a way of concretely validating the roommate’s perspective. I followed his advice, and I’m much happier with where the story ended up as a result.

Knowing I’d be revisiting these panels later in the story, I ended up taking the time to polish them up a little: I added details of a fence and path in the background, and tweaked the hand in the foreground. By this point, I was starting to get pretty tired of drawing; of the project in general. I’d put aside other things I was working on, and had academic assignments to deal with as well.

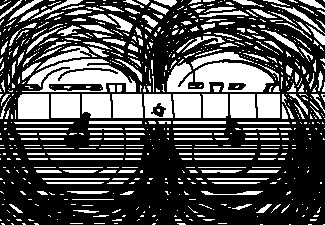

Panel 40 is one of a couple of panels that I feel would benefit from similar polishing. The idea was that it’d be a top-down view of the street, with two streetlamps providing light. The round shadows would give the impression of a pair of eyes or binoculars, with the lampposts themselves being pupils - tying into the paranoia described in the narration.

I thought that, by zooming out and letting the darkness creep into frame, I’d be able to force something of a tonal shift - and I think I was reasonably successful in this regard, particularly as the colours of the site itself flip once more. The prose also shifts slightly in tone, as the tail-end of the rant leads into the realisation that something’s wrong.

In its original form, people were confused by the image - the shading wasn’t nearly heavy enough, and the composition was unusual. This is where the art style works against me; I only have two colours to work with, and it can be hard to distinguish between detail and shadow at such a low resolution.

(There’s an animated music video for SIAMÉS’ “The Wolf” which uses a similar monochrome-plus-red palette to Retrace Steps - I saw it long before development on the story started and forgot about it until just now, so I don’t think it was an influence on the fanventure, but it’s definitely worth a watch!)

In the very first draft of the script, the protagonist found the key to their room in their hood. Seriously. Like, it’d start raining, they’d put their hood up and there’d be the key. I couldn’t think of a good ending, so I just came up with something daft and called it a day. The “doughnut offering” aspect of the story didn’t appear until I redrafted the script, a little ways into the film’s development (probably before we shot anything), but I can’t remember exactly how it came about. Originally, the script simply ended with the door getting slammed shut - the last line being a “what the actual fuck” from Sam/Alice.

(At the time when I was writing the story, I didn’t make a habit of buying mini doughnuts. I still don’t, except for on some occasions when I’m eating at a friend’s house and want to bring something low-commitment - even then, it’s usually cookies or muffins or full-sized doughnuts. Presumably, it was Retrace Steps which influenced that particular habit.)

On at least a literal level, the story’s message is “buy people doughnuts if you want them to be friends with you”. But naturally the actual message - and, I think, the reality - is that it’s not so transactional; really it’s just about assuming the best of people and being nice to them. Of course, there’s plenty of pitfalls in that approach - I’d be tempted to write a whole ‘nother story about them, if I didn’t think it’d end up being a little too dark and deconstructive. Be nice! That’s all I’m saying.

At least when I was writing the script, I’d actually planned for the protagonist to buy doughnuts from the local Sainsbury’s store. We have a Tesco store as well, plus a bunch of bigger supermarkets, but the Sainsbury’s is usually the quietest - it’s expensive and poorly-stocked. Plus, I just felt like it’d look better on-camera.

(If you’re not from the UK, all you need to know is that Tesco and Sainsbury’s are the two biggest supermarket chains. Well, apparently Asda overtook Sainsbury’s last month, but we’ll see how long that lasts. I’d say they’re generally pretty-much-indistinguishable, but at least in my mind I associate Sainsbury’s more closely with the middle classes - Tesco, meanwhile, is ubiquitous.)

When it came to adapting the script, I realised I could use any supermarket I wanted, and I picked Tesco. Specifically an “Express” store, which is a smaller shop found in town centres and the like. It fitted the story better - and besides, I’ve always liked the colloquialism “Tescos”. As in “aight mum I’m poppin off Tescos, our Jack says they’ve got a bogof on Lucozade, works out a quid for two litres so I’m buzzin, you after anythin or nah”.

(As part of let’s-call-it-research for the story, I found an eight-page thread on Mumsnet where a mum asks “am I being unreasonable to get really annoyed with people who call Tesco ‘Tescos’?” - this was immensely funny to me, and pretty much cemented my decision to use a real supermarket in the story as opposed to a made-up one.)

So yeah, panels 41-44 take place outside this Tescos. It was my brother - credited as “patipon” - who noted that I needed to use more solid black in the image. Most of what we discussed about the story took place in voice calls, which is a shame; historically, it’s been uncommon for me to solicit him for feedback on projects like this one. I consulted him on several of this story’s panels - he devotes much more time to graphics and artwork than I do - and his suggestions were always useful.

The prose on panel 43 is probably one of the bits I’m most proud of. It’s an awkward mix of metaphors coming from a character who isn’t used to being able to think when they’re at this particular place. I like the phrase “fumbled passes in the aisles” a lot.

(Gospar, one of my IRL friends and another prereader on Retrace Steps, occasionally graces us with the saying “ah, another day, another butchered social interaction”. Meanwhile, I went through a short-but-embarassing phase of butchering the trivial social interaction of “how are you?” by replying “I’m here” - something which I can’t excuse, but which I sure can immortalise in a webcomic.)

(All of this talk of Tescos reminds me of a draft I’ve had sitting around on my hard drive forever - the beginning of a first chapter which I wrote early in secondary school. It’s set in a post-apocalyptic snow-covered Britain where people travel around in sailboats on skis, and opens with some guy going into a buried Tescos for supplies. There, he runs into some orphan, who persuades the guy to let him hitch a ride on the snow-boat - snoat? Sure, whatever, snoat. The twist was going to be that the guy was planning to nuke some settlement, for reasons which I never wrote down and have since forgotten, and the kid would work this out and have to kill the guy to stop him. I note this simply to say that, while my stories may have gotten slightly less dumb and bad since I started writing, it seems that Tescos will be an enduring feature.)

(Wintry post-apocalyptic settings will also be an enduring feature, come to think of it: around the time I was writing Retrace Steps, I was also running a Dungeons & Dragons campaign for some friends which was basically standard fantasy - only it was set on an infinite-in-every-direction ski slope. I’m not a very good Dungeon Master, so I let the campaign die after a handful of sessions over the course of the year - which is a shame, because I’d planned a KILLER TWIST for that story too. Anyway, enough nonsense - back to Pokémon GO.)

I suppose at this point I should note that the two Pokémon you run into are Dugtrio and Magneton. These two are the evolved forms of Diglett and Magnemite, and are kinda-unique in that they’re literally just three of their previous stage grouped together. Hopefully, the symbolism of someone trying to obtain these Pokémon - and only succeeding after offering them a berry - should be clear enough.

(Note that the narration on panel 46 says you’re “not sure why this thing wants the berry” - at this point in the story, the protagonist doesn’t understand the significance of gestures like this.)

(I’ve yet to obtain either of these Pokémon in-game myself; Diglett and Magnemite are surprisingly hard to come by.)

The second half of the fanventure - from panel 51 all the way to panel 100 - takes place back inside the corridor. There’s a lot in the way of repeated panels with very little narration here - I was going for a more introspective tone, and this seemed like a good way to achieve that.

On panel 52, the narration notes that you plan to message your internet friends, then call your parents. It’s a little beat, but I felt like there was something kinda sad about the idea of having a closer connection with people you’ve never met than with your own parents. This is a pretty irrational way of looking at it - in my experience, most people on the internet who talk about their parents have pretty frayed relationships with them. Besides, there are plenty of cases where random peers will be better-equipped to help with specific problems - it’s just a case of balancing that against the fact that your own parents will probably care about you far more than any of those people.

I wanted to convey the image of someone who has the vast majority of their social interactions online. This theme is crucial to Homestuck itself, but while Homestuck demonstrates it by communicating its story pretty much entirely in chatlogs, in Retrace Steps I try to communicate it by showing everything except the chatlogs. Homestuck kills off everyone except a bunch of internet friends and their guardians; Retrace Steps just quietly omits everyone except a bunch of strangers standing in a room ha ha ha whoops spoilers.

Anyway, on panel 53, we start to see an environmental change caused by these strangers. For the first time, it seems like you’re not completely alone in this world.

The light's motion-activated - it turns on when you open the door, and then turns off again after around ten minutes. You've been gone much longer than that... meaning somebody else must have triggered it since then.

While working on this commentary, I decided that the original text of panel 55 - present in the story since its original release on 04/04/2019 and preserved in the above quote - was kinda overwrought and clumsy. Usually I’m pretty loathe to make edits to a story after it’s out on the internet, but this one felt acceptable - “Why was the light on when you arrived?” is much more succinct way of communicating what’s going on.

This panel’s artwork is also pretty clumsy - in case you’re having trouble parsing it, that’s supposed to be your head at the bottom. I tried to put a bit of light shading on it, but I’m not really happy with the result. Like I say, at this point I was getting pretty tired of drawing. Nah, I’m not changing it.

On panel 58, there’s a rare bit of onomatopoeia as you finally think to knock on the door. The negative space encroaches in from the right... but what does it hide?

Oh hey, it’s your roommate!

I think to a certain extent, this is another confusing image - Gitaxian observed that it didn’t really make much sense spatially. It’s kinda supposed to be a side-on cutaway, but that doesn’t really come across - I briefly tried adding a wood grain, to communicate that it’s the open door, but that didn’t make much sense at this scale and only confused matters further. In the end, I tweaked the boundary between the door and the corridor to give the impression of a couple of hinges and called it a day.

Panel 61 is, I guess, the big twist. You wanted to know where everyone is? Surprise! They’re in your room! Having a party! And you weren’t invited!

I wanted the reader to have a second to contemplate this, so the next couple of panels swap back-and-forth between you and the doorway. To underscore the silliness of the twist, one of the people in the back takes a big long sluuuurp from their solo cup - this breaks the spell, and you point for them all to leave.

It’s panel 67 that breaks the narration for the first time in the story. I wanted to present the roommate’s dialogue as a sharp contrast to the inner voice of the protagonist - it’s full of abbreviations, completely devoid of punctuation, and written entirely in solo-cup-red. The roommate simply sighs that you “never change”, and slams the door on you (with yet another cheeky bit of onomatopoeia appearing on-panel).

The idea that being around other people somehow supplants your inner thoughts is a very deliberate one - the commands cease entirely, the narration goes away. In these moments, we see you how everyone else sees you - as someone who’s pretty much entirely silent. On panels 69-70 there’s simply some ellipses, which kinda lengthen into a brief return of narration as you’re left on your own once more.

The reason this party’s taking place in “YOUR room” - as noted in the narration on panel 71 - is simply to show a feeling of entitlement. On the surface, you’re mad that you can’t get into your room - but you're also just feeling like people should invite you to parties.

Hopefully, the questions on panel 72 and panel 74 should be answering themselves by this point. You don’t know it at the time, but these will prove to be the last pieces of narration in the story.

After you’ve had some time to sit in the corridor and feel sorry for yourself, your roommate starts feeling bad and comes out to offer a sincere-but-backhanded apology. We’re into the last quarter of the comic now - starting with panel 76, there’s no text outside of what is spoken by your roommate.

The command used to advance to the next page has changed from “->” to “-->”. The story isn’t about just one person any more.

(This device is lifted directly from Homestuck, which switched from the command “==>” - used when the comic had four main characters - to “======>” when it swapped to a cast of twelve. Many fanventures - such as Oceanfalls - riff on this concept further, and mine is no exception.)

Out of all the text in the story, I’m probably happiest with the monologue on panel 79 and panel 80. I think it speaks for itself.

(As I always find myself saying, these commentaries kinda show that I don’t trust my stories to speak for themselves. I did hold off on writing this one for a couple of months, but there was lots of behind-the-scenes stuff I wanted to get on the record and I ultimately couldn’t help myself. The truth is that pretty much nobody reads these things - the commentaries, or the stories they’re for - and so the whole thing’s pretty much for my own benefit. I get to declare what I was going for, you get to decide whether or not I got it.)

Panels 81-95 are pretty much a frame-by-frame animation of you offering your roommate the doughnuts, and them leading you into the party. It’s basically two actions, but I try my best to draw them out as long as possible - by this point, the story’s said pretty much everything it needs to, and now it’s all just... emotional payoff? I feel like I’ve never been much good with character arcs, but I’m proud of how this turned out.

As promised, panels 96-99 are a straight repeat of panels 17-19 - the automatic lights turn off and the site’s colours flip for the last time, neatly mirroring the story’s first two panels in its last two.

Back in the kitchen, she opens the cupboard again and grabs the box of mini doughnuts.

She returns to her door and knocks again.

ALICE I bought doughnuts?

There is a long pause. The door suddenly opens and Bob pokes his head around, reaches out to grab like three doughnuts from the box, and then darts back inside. The door slams shut again.

ALICE Hey!

VII. Animation is harder than I thought.

This story is titled Retrace Steps because, in its original script form, it mostly focused on somebody retracing their steps in the hopes that they’d find their keys. The fanventure, however, drops this aspect of the plot entirely - leaving it with something of an artifact title. Maybe I should’ve come up with an alternate title, but I didn’t. On some level, it now simply refers to the trip to Tescos - on another, I think it implies that something’s been lost. I think it was the nagging feeling that the title no longer held enough significance that led me to create the story’s final flash.

If you haven’t read Homestuck, all you need to know is that pages with commands that are prefixed with an “[S]” are usually longer animations set to music, used for particularly important moments in the plot (or, just as often, for random chicanery). Having a flash of this sort is a point of prestige for fanventures - especially if it approaches any real length of complexity. I’d vaguely liked the idea of letting music play a fairly prominent role in the short film, and it felt right to return to those roots.

There wasn’t really any question as to which song I’d pick, either. See, back in college, I ran this terrible meme page called Summer Meme Sundae. It was absolute garbage. Please don’t click that link. Basically, its deal was that - for the latter half of its run - I tried to introduce something of a plot across the “memes”, wherein the page’s mascot got castaway and wound up in Australia. It was very silly and absolutely incomprehensible. Like I say, don’t look at it. This isn’t reverse psychology, it’s legitimately unfunny and bad. Anyway, the last post I made was something of a rudimentary flash in its own right - set to “Pizza for Breakfast” from The Meme Friends’ Last Week’s Pizza EP. I know basically nothing about The Meme Friends, but I thiiink they were some randos on 4chan’s /mu/ board.

It’s fair to say that the aesthetic of Last Week’s Pizza, which includes such tracks as “Cold Pizza”, “Everyone I Ever Loved is Now Dead”, and “Executive Pizza Party (Business)”, kinda appeals to me. If you’re reading Retrace Steps, the chances that you’ve heard the track before are next to nil - it comes with zero baggage. Moreover, it’s from a freely-distributed independent project created by a collective that hasn’t put out anything in years - it’s extremely unlikely that anybody’s going to come and tell me off for using it.

I specifically picked “No Forks, No Knives, It’s Pizza Time” because I felt like its tone was closest to that of the story, and because it has a relatively short runtime of just over two minutes - which still ended up being a little too long, but I don’t think it turned out too bad.

The flash opens on the image of the door in the corridor from the previous panel, which is gradually cut into smaller and smaller pieces by black lines until it disappears altogether. Cue title. One of the reasons I like the flash format - aside from the lack of antialiasing - is that you really have no way of telling how long the video’s going to be or what happens except by watching it. There’s none of YouTube’s functionality for skipping around - you’re forced to sit and watch the entire thing start-to-finish without stopping.

(I think Retrace Steps is definitely best read in a single sitting, and the final flash is a big part of that. My fourth prereader, Multivac of the Homestuck Discord server, was unable to watch the flash at first - I forget why - and found the story unclear. After watching the flash, he seemed to backpedal on this sentiment. Time will tell whether his initial assessment was correct; I picked Multivac because he’d previously responded positively to Everything Is Red Now, and because I’d usually consider his reaction to something to be a pretty decent rough baseline for the general reaction of the Homestuck Discord server.)

When stuff starts happening, it starts happening fast - you see the protagonist’s descent down the stairs again, but this time you see all three panels at once, as if there’s more than one person on the stairs. The minute you get outside, you start seeing entirely new people - many with red accents of some kind. Someone smoking, someone who’s been shopping, someone with a rucksack...

The people outside Tescos had a little more in the way of thought put into them. On the left, there’s a homeless person, and someone walking by with headphones on. Over on the far right, there’s someone holding their phone out in front of them - they’re wearing a hat famously worn by Ash Ketchum in the Pokémon anime, just in case there’s any doubt as to what game they’re playing. Someone sorta tired-looking crosses away from the rest. Everyone in the frame’s kinda collectively ignoring the two people holding hands.

(Textually, Retrace Steps is a story about... platonic fulfillment? If that’s a phrase that makes sense? My personal take is that the protagonist of this story struggles to create and maintain friendships. However, I tried to leave room for interpretation - particularly in terms of this section of the flash - and I think a reading definitely exists that brings in more romantic subtext.)

(Actually, I already kinda explored this last year - much less effectively - in Another Son. Like in that story, I wanted the audience to understand why the characters are lonely - but I used a much more sympathetic approach this time around, which crucially makes you actually want the story’s protagonist to stop being lonely. Something which bothers me about certain stories - and this is a really common failing of music videos, which lack the introspection of prose - is when the narrative takes its protagonist and frames things in a way which says “you should feel sorry for this person” while they proceed to do really unsympathetic things. If you’re going to give them a victory, the audience should feel like they actually deserve it!)

After a brief segment where you finally catch that Dugtrio, the flash cycles back through the various locations until we arrive back in the corridor. This sequence was added mostly to pad for time, but also serves to bring things full circle for the flash’s final shots. On the final beats of each bar - which fall on a higher note - the colours flip; this was purely an aesthetic choice.

The next section of the flash is just credits, which I kinda wanted to use to lull the audience into a false sense of security. See, the original plan was for the final image of the comic to just be you, standing completely alone, holding a solo cup - an ending which I think is much more ambiguous.

I still think this original ending provokes a much stronger emotional reaction - and indeed, it did at the time. As Gospar said, “also you sure you wanna keep the sad end / I think the fade out on others and the static / sort of implied they hadn’t changed?” Gitaxian agreed - “I think having the crowd fade to just the two of them, and then ending there, would be the best ending”. I’d already considered doing that, but had decided against it for reasons I’ve forgotten.

See, by this point in the story, you’ve made this connection with your roommate - but everyone else remains a stranger. I like this ending for its optimism: instead of saying “you're still alone”, it says “this is a good start”.

Oh, and remember the solo cup that’s been sitting up next to the ad? Yeah, that’s gone now.

She protests and knocks on the door again. Just before she kicks it, it suddenly opens again. Bob has like three doughnuts in his mouth.

BOB These are pretty good actually.

He grabs the whole box and opens the door fully, lightly beckoning for Alice to enter. She does so. The door closes.

We cut to inside the room. Everyone is standing in cramped, uncomfortable silence. Somebody hands Alice a red plastic cup.

CUT TO BLACK.

THE END

VIII. Knowing when to shut up is harder than I thought.

I just went to Tescos and bought a box of mini doughnuts.

(I didn’t set out to do that, but they were selling a single box for next to nothing and I felt like it was too serendipitous to ignore.)

It’s the end of the year. Classes finished over a month ago. I always end up staying for a good while after, because doing so gives me more time to work on projects like this, but most of my friends end up leaving before me - in other words, I don’t have anyone to share the doughnuts with.

(They have strawberry-flavoured icing and multicoloured sprinkles, and they taste frikkin’ great, so I can’t say I’m too beat up about that.)

I’ve played very little Pokémon GO since I started working on this fanventure. I... think I kinda ruined it for myself?

When I finished Retrace Steps, I was pretty sure I wasn’t going to do the fanventure format for a while. That lasted all of about four days, after which I started Huskyquest. It seems silly to give away this new fanventure’s plot here, so all I’ll say is this: it’s got dogs in it, it’s got more than three colours, and you should definitely drop it a like because I’ll hopefully be picking it back up again pretty soon.

In the meantime, feel free to peruse all the other things I made on this blog! There should be another project coming out here very soon, so if you wanna be informed when that happens, drop me a follow either here or on twitter. And of course, if you have any questions, my ask box is always open. Thanks for reading!

...You’re still here?

It’s over.

Pokémon GO home.

> Go.

#MSPA#MS Paint Adventures#MSPFA#MS Paint Fan Adventures#Homestuck#fanventure#Retrace Steps#The Wadapan#04/04/2019#31/05/2019

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

What It Takes To Be A Voice Actor REDUX

In 2015 I wrote a blog about what it takes to be a successful voice actor. I have since come to feel that I was perhaps a little too discouraging in tone. There are plenty of voices in the world to say “no” to your dreams. I don’t wish to be one of them. So here is my previous article on the matter, re-released and annotated to reflect my current thinking.

Old essay in plain text or bold. New thoughts struck throughstruck through and replaced with italics.

I’m going to offer two kinds of advice. First I will touch on passion, work ethic and other similarly rarefied intangibles—the habits and the mentality required to succeed. Only then will I move on to some nuts-and-bolts advice—the stuff you can take to the bank… or the booth, as the case may be.

A few caveats:

I am not a voice actor.

I have directed many wonderful voice actors. I know a lot about what “the biz” is looking for, and I know what I myself am looking for in a good voice actor. But I have done very little professional acting.

This is art, not science.

This is an art form, and like any art form it is squishy. There are no hard-and-fast rules, just guidelines, and the guidelines are riddled with exceptions. Like…keeping your eyes open is a basic rule of effective stand-up comedy, right? Well, tell that to Gilbert Gottfried or Mitch Hedburg. The same goes for VO—a certain amount of wiggle room is inherent.

Some people might disagree with me.

That’s okay! My opinion is subjective, and the industry is always in flux. There are lots of different opinions out there, and if you are a professional and you have one, please send it to me so I can make it available here, and incorporate it into my own understanding.

There is no magic bullet.

It is not a 1+1=you’rethenextNolanNorth scenario. You can follow all these guidelines and still find yourself working at The Cheesecake Factory for years. There is no shame in that. A big ingredient to success is luck. The other major ingredient is persistence and that brings me to…

Part 1: This Is A Very Hard Job To Get

Before you decide to become a voice actor it is essential that you have an understanding of what it will take to break in.

You must love it enough to spend as many as five years breaking in, working other jobs, spending money on classes and demos, and being relentlessly hardworking and self-improving, without landing a single gig. Some people waltz right in. Others have to batter down brick walls. You must be prepared to do the latter. If you are not, do yourself a favor and pick a different career.

Kal 2017: Actually, try this career. ALWAYS try to follow your dreams. You and you alone will know if you’ve had enough and want to do something else. Might take a month, might take five years, might be never. Pick the career you love, don’t let anyone tell you not to.

Let’s revisit those words “relentlessly hardworking and self-improving.”

Throughout your career, but particularly when you are breaking in, you will be competing against the very best actors in the world. You might be talented to begin with, but that is not enough. You MUST MUST MUST push yourself to be better, ALWAYS. I guarantee that your competition will.

Kal 2017: This remains true, but I temper it by saying do not worry if you are not the best to start with. Skills can be built over time. The most important thing is that you have a fun and happy life doing something you enjoy. You can actually hear the sound of stress in a performance, and it’s not a good sound. Try to relax and have fun!

This means acknowledging early-on that you always have something to learn, and then being proactive about learning it. Read books, and take classes.

TAKE CLASSES!

Take voice acting classes, take stage acting classes, take directing classes, take breath work, take improv, take puppetry, take singing lessons. If you can, take an animation class or two. Since you’re going into audio, you might try to learn a bit about audio engineering/editing.

Kal 2017: Side note on this last idea. It is a great idea, if you are moving to Hollywood to do something fun and crazy, to pick up a production/postproduction skill like film/video editing, audio engineering/mixing/mastering, AfterEffects/graphics etc. These disciplines are a great and generally flexibly scheduled way to make a good living while you try to break into the job you’re passionate about.

Why? Because people love to shoot and record, but hate to edit/do post. Post work is an art, but it is also a trade, like plumbing—labor that HAS to get done before anything can be released. If you can get good and fast at this, and you don’t mind spending hours working on reality TV, web content, and infomercials, you can make some sweet bank. You’ll often be your own boss, and even when you’re not, postproduction people tend to be the most chill. Plus you’ll likely make some great contacts within your chosen field as well.

For instance, you can work at a recording studio, and meet voice actors, directors, and producers who have already broken in. If you do an awesome job with a good attitude, and help them be successful in their endeavors, they will be predisposed to say “yes” down the road when you ask for that audition, that recommendation to an agent, that free coaching session.

Believe me, anything and everything related to performance or art will be valuable, even if it is not VO-based.

I want to give a particular shout out to Shakespearean acting techniques, particularly those pioneered by Kristen Linklater. Almost all the best actors I have known have a serious grounding in that material.

Kal 2017: This is a great time to recommend some LA coaches who are awesome. I really like:

Bill Holmes @vodoctor

Andrea Romano

Kalmenson & Kalmenson @kalmenson

The Voice Actor’s Network with Hope Levy @hopelevysings

JB Blanc @thejbblanc — Side note about this one. In addition to being a fantabulous actor, director, and coach, JB is also one of the leading experts on dialects. If you are international and looking to lose your accent, JB is the guy. If you are looking to acquire an accent for a role, JB is the guy.

And of course, me @kalelbogdanove

I’ll try to update with some reliable classes/coaches in other cities.

Also, remember to take movement classes like dance or martial arts. I know it sounds odd, since you will not be physically seen by anyone, but having an understanding of your body’s kinesthetics will improve your work.

Brian T. Delaney (Male Soul Survivor in Fallout 4) isn’t just one of the most physical voice actors I know, he is one of the most physical actors I know, full-stop. This does two things for him. First, it gives him technical control in the booth—he almost never goes off-mic, or hits the stand, or rustles his clothing (which is astonishing, given how much he moves around). Second, it invests all his game work with a sense of space and a sense of place—a layer and texture of reality that could not sound less like a guy reading a line—and his combat work in particular with a breathtaking degree of authenticity.

In short… learn how to move.

“BUT I’M ALREADY AWESOME,” you say.

Or, “I’ve already done a little voice work,” or some other excuse. Doesn’t matter. All the best working voice actors take classes constantly. They do not rest on their laurels. The best directors take classes too, including me. (He said with pompous implications.)

If you can’t afford classes, form a group of like-minded actors and practice together regularly. Watch videos on YouTube. Make your continuing education a priority.

The great thing is, these classes are FUN! You’ll meet like-minded artists! You’ll make great projects! You’ll feel impressive and confident as your abilities grow and grow! Hell, you might get laid.

The point is that while the waiting and the day jobs are can be grueling, the work itself is fun. And if you don’t find it fun… do yourself a favor and pick a different career.

Kal 2017: Again, you’ll know. It’s okay to have a bad class/day/week/month. Stick to it! You can do it! Remain open and willing to grow, and you will likely succeed.

Part 2: This Is A Very Hard Job To Do

Voice over looks easy but it is VERY DIFFICULT—particularly in games. Take a moment and go on a journey of imagination with me:

Imagine four hours at a time in a booth that is as silent as The Surface of The Moon, unless the director has the talk-back open.

Imagine making seventy major emotional adjustments an hour. (By contrast, on-camera actors make between 2 and 10 per DAY.)

Imagine formulating a performance, delivering it, absorbing a note, reformulating, and redelivering in as little as 30 seconds.

Now imagine doing that 300-600 times in four hours.

This can be extremely tough. You must be able to clear as many as 150 lines an hour, with an average of 70. (Animation is closer to 20-30.) You must be a MUTHAFUCKIN’ BAWSE at cold-reading. (Better always to give a strong-but-wrong take right off the bat, than fiddle-fart around with broken half-takes.)

And line 600 has to be as strong and fresh as line 001.

Do not confuse fun and easy. This is a very fun job when it’s done right. It is ALWAYS very hard work. And if you’re not ready for hard work… do I have to say it again? You’re smart. I don’t. You get the idea.

Kal 2017: I really don’t. Even at its most difficult this is a pretty great job, one of the few remaining that is protected by a strong union. It is hard, but it is also a blast.

Part 3: A Great Voice Actor

I’ll keep this straightforward. A great voice actor is…

Punctual. Be on time. On time means 5-10 minutes early.

Friendly, but not unctuous. Don��t be a sourpuss, don’t climb in anyone’s lap.

Patient. Sometimes (rarely) writers and clients and producers will test your patience, or act outright rude. Try to be Zen. A good director will shield you from as much of this as possible.

CONFIDENT. I’m gonna repeat this—

CONFIDENT! Always give me a strong-but-wrong choice instead of a hesitant garble. I cannot stress this enough. If you are second-guessing yourself, you are wasting everyone’s time undercutting your talent and hard work. Be kind to yourself by standing by your ability, and let the director tell you if we need to adjust the performance.

A great listener. Redirect is gonna come at you thick and fast and you will have to pay close attention!

Dedicated. You may work on some dumb projects in your life. Doesn’t matter. You give every single stupid burger commercial your all. It is your job. Do not phone it in. Do not EVER EVER EVER show up drunk, high, or bored.

A strong reader. No two ways around this one. You have to pick stuff up off the page very rapidly. Kal 2017: Yes, okay, but also don’t be afraid to ask for the script in advance. Some won’t be willing to share it, but many simply assume you do not want it ahead of time. (Many voice actors don’t.) In that case they will be overjoyed to share it so you can rehearse. It never hurts to ask.

Not afraid to ask questions. If you don’t understand a line, or a piece of direction, just ASK ME ABOUT IT. Kal 2017: Please do this. Don’t be shy. We’re here to help YOU, so you can please THE CLIENT, which in turn makes US look good.

Excited to collaborate. You should bring ideas to the material. You should also be willing to totally chuck them and try something new in the spirit of exploration, even if you think it’s gonna be garbage.

Resilient. If you fuck up, just do another one. :) Kal 2017: This is related to confident. It’s okay to mess up. All the pros do. Don’t be embarrassed. Try not to get in your head. Just climb back on that horse.

Part 4: Upsides