#wilhelm liebknecht

Link

Wilhelm Martin Philipp Christian Ludwig Liebknecht was a German socialist and one of the principal founders of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). His...

Link: Wilhelm Liebknecht

0 notes

Video

Bronzener Bärenkopf by Pascal Volk

Via Flickr:

Vier von ihnen sind an der Liebknechtbrücke angebracht. Diese wurden bereits an der damaligen Kaiser-Wilhelm-Brücke angebracht. Während des 2. Weltkriegs wurden sie abgenommen und sollten eingeschmolzen werden. Das geschah aber nicht. 1945 wurden die Bären in die USA verkauft. Nach der Wende kamen die Bären zurück nach Berlin und wurden an der Liebknechtbrücke angebracht.

#Berlin#Berlin Mitte#Europe#Germany#Liebknechtbrücke#Mitte#28mm#68895#Kavalierbrücke#Kaiser-Wilhelm-Brücke#Liebknecht Bridge#Sommer#Summer#Verano#Skulptur#sculpture#escultura#Canon EOS R7#Canon RF 28-70mm F2L USM#DxO PhotoLab#flickr

0 notes

Text

Bei Karovier gefunden

Das revolutionäre Erbe Rosa Luxemburgs und die deutsche Arbeiterbewegung

Wilhelm Pieck:

„… ein Adler kann wohl manchmal auch tiefer hinabsteigen als ein Huhn, aber nie kann ein Huhn in solche Höhen steigen wie ein Adler. Rosa Luxemburg irrte in der Frage der Unabhängigkeit Polens; sie irrte 1903 in der Beurteilung des Menschewismus; sie irrte, als sie im Juli 1904 neben Plechanow, Vandervelde,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

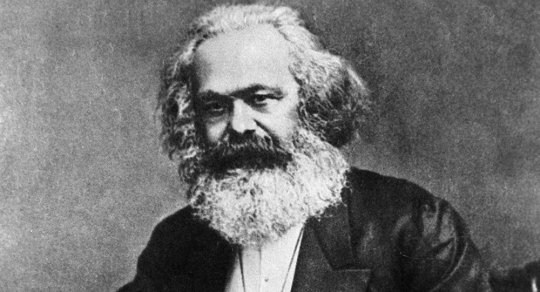

On this day, 5 May 1818, Karl Marx was born in Trier, Germany. Living until the age of 64, Marx was a journalist, revolutionary socialist, philosopher and economist, and one of the most influential figures in world history. Like all of us, he had his flaws, but he dedicated his life to the the cause of the working class, and inspired hundreds of millions with his works, including Capital. Over a century later, Capital remains the most incisive critique of the capitalist system. While his ideas have been used by some to justify politicians and parties acting on behalf of the working class, Marx was clear that ultimately "The emancipation of the working class must be the work of the working class itself." Though his wife was from a wealthy background, Marx and his family often lived in abject poverty, and four of their children died in infancy. His children who survived to adulthood all became socialist activists in their own right, including his eldest daughter Jenny who also died before him. Despite his often difficult circumstances and the tragedy in his personal life, Marx was also well up for a laugh. For example his friend and biographer Wilhelm Liebknecht recounted an evening pub crawl in west London where, forced into a tactical retreat after drunkenly slagging off a bunch of English people, Marx and his friends began smashing street lamps by throwing stones at them, until being spotted by a policeman, whereupon they had to flee down back streets and alleyways. In the Communist Manifesto he co-wrote with Friedrich Engels, Marx noted that "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles." This is something we hope to illustrate at Working Class History. You can get works by and about Marx here in our online store: https://shop.workingclasshistory.com/collections/all/karl-marx https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=620813370091882&set=a.602588028581083&type=3

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy birthday, Wilhelm Pieck! (January 3, 1876)

President of the German Democratic Republic from 1949 to 1960, Wilhelm Pieck was born into a Catholic family in what is now Poland. A carpenter by trade, Pieck's involvement with the carpenters' union led him to join the Social Democratic Party of Germany at age 19. Pieck was a leading voice in the party's left wing, and he was jailed for opposing German involvement in World War I, joining the new Communist Party of Germany after he was released. He narrowly escaped being murdered alongside Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht and later fled Germany as the Nazis took power, settling for a time in Moscow. After World War II, Pieck returned to Germany and assumed leadership of the new socialist government of eastern Germany. He died in 1960.

96 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Revolutionary Leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, Murdered on This Date in 1919.

The murders were of Luxemburg and Liebknecht were committed by the Freikorps, mostly demobilized, footlose and unemployed former soldiers many of whom would soon become nazis, under the orders of the Social Democrat Minister of Defense of the new Weimar Republic, Gustav Noske.

--

“...Lay down your weapons, you soldiers at the front. Lay down your tools, you workers at home. Do not let yourselves be deceived any longer by your rulers, the lip patriots, and the munitions profiteers. Rise with power and seize the reins of government. Yours is the force. To you belongs the right to rule. Answer the call for freedom and win your own war for liberty…Comrades! Soldiers! Sailors! And you workers! Arise by regiments and arise by factories. Disarm your officers, whose sympathies and ideas are those of the ruling classes. Conquer your foremen, who are on the side of the present order. Announce the fall of your masters and demonstrate your solidarity...” Karl Leibknecht, calling for social revolution in Germany, 1918

“Shamed, dishonored, wading in blood and dripping with filth – there stands bourgeois society. This is it [in reality]. Not all spic and span and moral, with pretense to culture, philosophy, ethics, order, peace, and the rule of law – but the ravening beast, the witches’ sabbath of anarchy, a plague to culture and humanity. Thus it reveals itself in its true, its naked form.” Rosa Luxemburg, on the growing horrors of World War I, in “The Junius Pamphlet,” 1915

“WE HAVE suffered two heavy losses at once which merge into one enormous bereavement. There have been struck down from our ranks two leaders whose names will be for ever entered in the great book of the proletarian revolution: Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. They have perished. They have been killed. They are no longer with us!

Karl Liebknecht’s name, though already known, immediately gained world-wide significance from the first months of the ghastly European slaughter. It rang out like the name of revolutionary honour, like a pledge of the victory to come. In those first weeks when German militarism celebrated its first orgies and feted its first demonic triumphs; in those weeks when the German forces stormed through Belgium brushing aside the Belgian forts like cardboard houses; when the German 420mm cannon seemed to threaten to enslave and bend all Europe to Wilhelm; in those days and weeks when official German social-democracy headed by its Scheidemann and its Ebert bent its patriotic knee before German militarism to which everything, at least it seemed, would submit—both the outside world (trampled Belgium and France with its northern part seized by the Germans) and the domestic world (not only the German junkerdom, not only the German bourgeoisie, not only the chauvinist middle-class but last and not least the officially recognized party of the German working class); in those black, terrible and foul days there broke out in Germany a rebellious voice of protest, of anger and imprecation; this was the voice of Karl Liebknecht. And it resounded throughout the whole world!

In France where the mood of the broad masses then found itself under the heel of the German onslaught; where the ruling party of French social-patriots declared to the proletariat the necessity to fight not for life but until death (and how else when the ‘whole people’ of Germany is craving to seize Paris!); even in France Liebknecht’s voice rang out warning and sobering, exploding the barricades of lies, slander and panic. It could be sensed that Liebknecht alone reflected the stifled masses.

In fact however even then he was not alone as there came forward hand in hand with him from the first day of the war the courageous, unswerving and heroic Rosa Luxemburg. The lawlessness of German bourgeois parliamentarism did not give her the possibility of launching her protest from the tribune of parliament as Liebknecht did and thus she was less heard. But her part in the awakening of the best elements of the German working class was in no way less than that of her comrade in struggle and in death, Karl Liebknecht. These two fighters so different in nature and yet so close, complemented each other, unbending marched towards a common goal, met death together and enter history side by side.

Karl Liebknecht represented the genuine and finished embodiment of an intransigent revolutionary. In the last days and months of his life there have been created around his name innumerable legends: senselessly vicious ones in the bourgeois Press, heroic ones on the lips of the working masses.

In his private life Karl Liebknecht was—alas!—already he merely was the epitomy of goodness, simplicity and brotherhood. I first met him more than 15 years ago. He was a charming man, attentive and sympathetic. It could be said that an almost feminine tenderness, in the best sense of this word, was typical of his character. And side by side with this feminine tenderness he was distinguished by the exceptional heart of a revolutionary will able to fight to the last drop of blood in the name of what he considered to be right and true. His spiritual independence appeared already in his youth when he ventured more than once to defend his opinion against the incontestable authority of Bebel. His work amongst the youth and his struggle against the Hohenzollern military machine was marked by great courage. Finally he discovered his full measure when he raised his voice against the serried warmongering bourgeoisie and the treacherous social-democracy in the German Reichstag where the whole atmosphere was saturated with miasmas of chauvinism. He discovered the full measure of his personality when as a soldier he raised the banner of open insurrection against the bourgeoisie and its militarism on Berlin’s Potsdam Square. Liebknecht was arrested. Prison and hard labour did not break his spirit. He waited in his cell and predicted with certainty. Freed by the revolution in November last year, Liebknecht at once stood at the head of the best and most determined elements of the German working class. Spartacus found himself in the ranks of the Spartacists and perished with their banner in his hands.

Rosa Luxemburg’s name is less well-known in other countries than it is to us in Russia. But one can say with all certainty that she was in no way a lesser figure than Karl Liebknecht. Short in height, frail, sick, with a streak of nobility in her face, beautiful eyes and a radiant mind she struck one with the bravery of her thought. She had mastered the Marxist method like the organs of her body. One could say that Marxism ran in her blood stream.

I have said that these two leaders, so different in nature, complemented each other. I would like to emphasize and explain this. If the intransigent revolutionary Liebknecht was characterized by a feminine tenderness in his personal ways then this frail woman was characterized by a masculine strength of thought. Ferdinand Lassalle once spoke of the physical strength of thought, of the commanding power of its tension when it seemingly overcomes material obstacles in its path. That is just the impression you received talking to Rosa, reading her articles or listening to her when she spoke from the tribune against her enemies. And she had many enemies! I remember how, at a congress at Jena I think, her high voice, taut like a wire, cut through the wild protestations of opportunists from Bavaria, Baden and elsewhere. How they hated her! And how she despised them! Small and fragilely built she mounted the platform of the congress as the personification of the proletarian revolution. By the force of her logic and the power of her sarcasm she silenced her most avowed opponents. Rosa knew how to hate the enemies of the proletariat and just because of this she knew how to arouse their hatred for her. She had been identified by them early on.

From the first day, or rather from the first hour of the war, Rosa Luxemburg launched a campaign against chauvinism, against patriotic lechery, against the wavering of Kautsky and Haase and against the centrists’ formlessness; for the revolutionary independence of the proletariat, for internationalism and for the proletarian revolution.

Yes, they complemented one another!

By the force of the strength of her theoretical thought and her ability to generalize Rosa Luxemburg was a whole head above not only her opponents but also her comrades. She was a woman of genius. Her style, tense, precise, brilliant and merciless, will remain for ever a true mirror of her thought.

Liebknecht was not a theoretician. He was a man of direct action. Impulsive and passionate by nature, he possessed an exceptional political intuition, a fine awareness of the masses and of the situation and finally an unrivalled courage of revolutionary initiative.

An analysis of the internal and international situation in which Germany found herself after November 9, 1918, as well as a revolutionary prognosis could and had to be expected first of all from Rosa Luxemburg. A summons to immediate action and, at a given moment, to armed uprising would most probably come from Liebknecht. They, these two fighters, could not have complemented each other better.

Scarcely had Luxemburg and Liebknecht left prison when they took each other hand in hand, this inexhaustible revolutionary man and this intransigent revolutionary woman and set out together at the head of the best elements of the German working class to meet the new battles and trials of the proletarian revolution. And on the first steps along this road a treacherous blow has on one day, struck both of them down.

To be sure reaction could not have chosen more illustrious victims. What a sure blow! And small wonder! Reaction and revolution knew each other well as in this case reaction was personified in the guise of the former leaders of the former party of the working class, Scheidemann and Ebert whose names will be for ever inscribed in the black book of history as the shameful names of the chief organizers of this treacherous murder.

It is true that we have received the official German report which depicts the murder of Liebknecht and Luxemburg as a street “misunderstanding” occasioned possibly by a watchman’s insufficient vigilance in the face of a frenzied crowd. A judicial investigation has been arranged to this end. But you and I know too well how reaction lays on this sort of spontaneous outrage against revolutionary leaders; we well remember the July days that we lived through here within the walls of Petrograd, we remember too well how the Black Hundred bands, summoned by Kerensky and Tsereteli to the fight against the Bolsheviks, systematically terrorized the workers, massacred their leaders and set upon individual workers in the streets. The name of the worker Voinov, killed in the course of a “misunderstanding” will be remembered by the majority of you. If we had saved Lenin at that time then it was only because he did not fall into the hands of frenzied Black Hundred bands. At that time there were well-meaning people amongst the Mensheviks and the Social Revolutionaries who were disturbed by the fact that Lenin and Zinoviev, who were accused of being German spies, did not appear in court to refute the slander. They were blamed for this especially. But at what court? At that court along the road to which Lenin would be forced to “flee”, as Liebknecht was, and if Lenin was shot or stabbed, the official report by Kerensky and Tsereteli would state that the leader of the Bolsheviks was killed by the guard while attempting to escape. No, after the terrible experience in Berlin we have ten times more reason to be satisfied that Lenin did not present himself to the phony trial and yet more to violence without trial.

But Rosa and Karl did not go into hiding. The enemy’s hand grasped them firmly. And this hand choked them. What a blow! What grief! And what treachery! The best leaders of the German Communist Party are no more—our great comrades are no longer amongst the living. And their murderers stand under the banner of the Social-Democratic party having the brazenness to claim their birthright from no other than Karl Marx! “What a perversion! What a mockery!&#rdquo; Just think, comrades, that “Marxist” German Social-Democracy, mother of the working class from the first days of the war, which supported the unbridled German militarism in the days of the rout of Belgium and the seizure of the northern provinces of France; that party which betrayed the October Revolution to German militarism during the Brest peace; that is the party whose leaders, Scheidemann and Ebert, now organize black bands to murder the heroes of the International, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg!

What a monstrous historical perversion! Glancing back through the ages you can find a certain parallel with the historical destiny of Christianity. The evangelical teaching of the slaves, fishermen, toilers, the oppressed and all those crushed to the ground by slave society, this poor people’s doctrine which had arisen historically was then seized upon by the monopolists of wealth, the kings, aristocrats, archbishops, usurers, patriarchs, bankers and the Pope of Rome, and it became a cover for their crimes. No, there is no doubt however, that between the teaching of primitive Christianity as it emerged from the consciousness of the plebeians and the official catholicism or orthodoxy, there still does not exist that gulf as there is between Marx’s teaching which is the nub of revolutionary thinking and revolutionary will and those contemptible left-overs of bourgeois ideas which the Scheidemanns and Eberts of all countries live by and peddle. Through the intermediary of the leaders of social-democracy the bourgeoisie has made an attempt to plunder the spiritual possessions of the proletariat and to cover up its banditry with the banner of Marxism. But it must be hoped, comrades, that this foul crime will be the last to be charged to the Scheidemanns and the Eberts. The proletariat of Germany has suffered a great deal at the hands of those who have been placed at its head; but this fact will not pass without trace. The blood of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg cries out. This blood will force the pavements of Berlin and the stones of that very Potsdam Square on which Liebknecht first raised the banner of insurrection against war and capital to speak up. And one day sooner or later barricades will be erected out of these stones on the streets of Berlin against the servile grovellers and running dogs of bourgeois society, against the Scheidemanns and the Eberts!

In Berlin the butchers have now crushed the Spartacists’ movement: the German communists. They have killed the two finest inspirers of this movement and today they are maybe celebrating a victory. But there is no real victory here because there has not been yet a straight, open and full fight; there has not yet been an uprising of the German proletariat in the name of the conquest of political power. There has been only a mighty reconnoitering, a deep intelligence mission into the camp of the enemy’s dispositions. The scouting precedes the conflict but it is still not the conflict. This thorough scouting has been necessary for the German proletariat as it was necessary for us in the July days.

The misfortune is that two of the best commanders have fallen in the scouting expedition. This is a cruel loss but it is not a defeat. The battle is still ahead.

The meaning of what is happening in Germany will be better understood if we look back at our own yesterday. You remember the course of events and their internal logic. At the end of February, the popular masses threw out the Tsarist throne. In the first weeks the feeling was as if the main task had been already accomplished. New men who came forward from the opposition parties and who had never held power here took advantage at first of the trust or half-trust of the popular masses. But this trust soon began to break to splinters. Petrograd found itself in the second stage of the resolution at its head as indeed it had to be. In July as in February it was the vanguard of the revolution which had gone out far in front. But this vanguard which had summoned the popular masses to open struggle against the bourgeoisie and the compromisers, paid a heavy price for the deep reconnaissance it carried out.

In the July Days the Petrograd vanguard broke from Kerensky’s government. This was not yet an insurrection as we carried through in October. This was a vanguard clash whose historical meaning the broad masses in the provinces still did not appreciate. In this collision the workers of Petrograd revealed before the popular masses not only of Russia but of all countries that behind Kerensky there was no independent army, and that those forces which stood behind him were the forces of the bourgeoisie, the white guard, the counter-revolution.

Then in July we suffered a defeat. Comrade Lenin had to go into hiding. Some of us landed in prison. Our papers were suppressed. The Petrograd Soviet was clamped down. The party and Soviet printshops were wrecked, everywhere the revelry of the Black Hundreds reigned. In other words there took place the same as what is taking place now in the streets of Berlin. Nevertheless none of the genuine revolutionaries had at that time any shadow of doubt that the July Days were merely the prelude to our triumph.

A similar situation has developed in recent days in Germany too. As Petrograd had with us, Berlin has gone out ahead of the rest of the masses; as with us, all the enemies of the German proletariat howled: “we cannot remain under the dictatorship of Berlin; Spartacist Berlin is isolated; we must call a constituent assembly and move it from red Berlin—depraved by the propaganda of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg—to a healthier provincial city in Germany.” Everything that our enemies did to us, all that malicious agitation and all that vile slander which we heard here, all this translated into German was fabricated and spread round Germany directed against the Berlin proletariat and its leaders, Liebknecht and Luxemburg. To be sure the Berlin proletariat’s intelligence mission developed more broadly and deeply than it did with us in July, and that the victims and the losses are more considerable there is true. But this can be explained by the fact that the Germans were making history which we had made once already; their bourgeoisie and military machine had absorbed our July and October experience. And most important, class relations over there are incomparably more defined than here; the possessing classes incomparably more solid, more clever, more active and that means more merciless too.

Comrades, here there passed four months between the February revolution and the July days; the Petrograd proletariat needed a quarter of a year in order to feel the irresistible necessity to come out on the street and attempt to shake the columns on which Kerensky’s and Tsereteli’s temple of state rested. After the defeat of the July days, four months again passed during which the heavy reserve forces from the provinces drew themselves up behind Petrograd and we were able, with the certainty of victory, to declare a direct offensive against the bastions of private property in October 1917.

In Germany, where the first revolution which toppled the monarchy was played out only at the beginning of November, our July Days are already taking place at the beginning of January. Does this not signify that the German proletariat is living in its revolution according to a shortened calendar? Where we needed four months it needs two. And let us hope that this schedule will be kept up. Perhaps from the German July Days to the German October not four months will pass as with us, but less—possibly two months will turn out sufficient or even less. But however event proceed, one thing alone is beyond doubt: those shots which were sent into Karl Liebknecht’s back have resounded with a mighty echo throughout Germany. And this echo has rung a funeral note in the ears of the Scheidemanns and the Eberts, both in Germany and elsewhere.

So here then we have sung a requiem to Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. The leaders have perished. We shall never again see them alive. But, comrades, how many of you have at any time seen them alive? A tiny minority. And yet during these last months and years Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg have lived constantly among us. At meetings and at congresses you have elected Karl Liebknecht honorary president. He himself has not been here—he did not manage to get to Russia—and all the same he was present in your midst, he sat at your table like an honoured guest, like your own kith and kin—for his name had become more than the mere title of a particular man, it had become for us the designation of all that is best, courageous and noble in the working class. When any one of us has to imagine a man selflessly devoted to the oppressed, tempered from head to foot, a man who never lowered his banner before the enemy, we at once name Karl Liebknecht. He has entered the consciousness and memory of the peoples as the heroism of action. In our enemies’ frenzied camp when militarism triumphant had trampled down and crushed everything, when everyone whose duty it was to protest fell silent, when it seemed there was nowhere a breathing-space, he, Karl Liebknecht, raised his fighter’s voice. He said “You, ruling tyrants, military butchers, plunderers, you, toadying lackies, compromisers, you trample on Belgium, you terrorize France, you want to crush the whole world, and you think that you cannot be called to justice, but I declare to you: we, the few, are not afraid of you, we are declaring war on you and having aroused the masses we shall carry through this war to the end!” Here is that valour of determination, here is that heroism of action which makes the figure of Liebknecht unforgettable to the world proletariat.

And at his side stands Rosa, a warrior of the world proletariat equal to him in spirit. Their tragic death at their combat positions couples their names with a special, eternally unbreakable link. Henceforth they will be always named together: Karl and Rosa, Liebknecht and Luxemburg!

Do you know what the legends about saints and their eternal lives are based upon? On the need of the people to preserve the memory of those who stood at their head and who guided them in one way or another; on the striving to immortalize the personality of the leaders with the halo of sanctity. We, comrades, have no need of legends, nor do we need to transform our heroes into saints. The reality in which we are living now is sufficient for us, because this reality is in itself legendary. It is awakening miraculous forces in the spirit of the masses and their leaders, it is creating magnificent figures who tower over all humanity.

Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg are such eternal figures. We are aware of their presence amongst us with a striking, almost physical immediacy. At this tragic hour we are joined in spirit with the best workers of Germany and the whole world who have received this news with sorrow and mourning. Here we experience the sharpness and bitterness of the blow equally with our German brothers. We are internationalists in our sorrow and mourning just as much as we are in all our struggles.

For us Liebknecht was not just a German leader. For us Rosa Luxemburg was not just a Polish socialist who stood at the head of the German workers. No, they are both kindred of the world proletariat and we are all tied to them with an indissoluble spiritual link. Till their last breath they belonged not to a nation but to the International!

For the information of Russian working men and women it must be said that Liebknecht and Luxemburg stood especially close to the Russian revolutionary proletariat and in its most difficult times at that. Liebknecht’s flat was the headquarters of the Russian exiles in Berlin. When we had to raise the voice of protest in the German parliament or the German press against those services which the German rulers were affording Russian reaction we above all turned to Karl Liebknecht and he knocked at all the doors and on all the skulls, including the skulls of Scheidemann and Ebert to force them to protest against the crimes of the German government. And we constantly turned to Liebknecht when any of our comrades needed material support. Liebknecht was tireless as the Red Cross of the Russian revolution.

At the congress of German Social-Democrats at Jena which I have already referred to, where I was present as a visitor, I was invited by the presidium on Liebknecht’s intiative to speak on the resolution moved by the same Liebknecht condemning the violence and the brutality of the Tsarist government in Finland. With the greatest diligence Liebknecht prepared his own speech collecting facts and figures and questioning me in detail on the customs relations between Tsarist Russia and Finland. But before the matter reached the platform (I was to speak after Liebknecht) a telegram report on the assassination of Stolypin in Kiev had been received. This telegram produced a great impression at the congress. The first question which arose amongst the leadership was: would it be appropriate for a Russian revolutionary to address a German congress at the same time as some other Russian revolutionary had carried out the assassination of the Russian Prime Minister? This thought seized even Bebel: the old man who stood three heads above the other Central Committee members, did not like any “needless” complications. He at once sought me out and subjected me to questions: “What does the assassination signify? Which party could be responsible for it? Didn’t I think that in these conditions that by speaking I would attract the attention of the German police?” “Are you afraid that my speech will create certain difficulties?” I asked the old man cautiously. “Yes”, answered Bebel, “I admit I would prefer it if you did not speak.” “Of course,” I answered, “in that case there can be no question of my speaking.” And on that we parted.

A minute later, Liebknecht literally came running up to me. He was agitated beyond measure. “Is it true that they have proposed you do not speak?” he asked me. “Yes,” I replied, “I have just settled this matter with Bebel.” “And you agreed?” “How could I not agree,” I answered justifying myself, “seeing that I am not master here but a visitor.” “This is an outrageous act by our presidium, disgusting, an unheard-of scandal, miserable cowardice!” etc., etc. Liebknecht gave vent to his indignation in his speech where he mercilessly attacked the Tsarist government in defiance of backstage warnings by the presidium who had urged him not to create “needless” complications in the form of offending his Tsarist majesty.

From the years of her youth Rosa Luxemburg stood at the head of those Polish Social-Democrats who now together with the so-called “Lewica” i.e. the revolutionary Section of the Polish Socialist Party have joined to form the Communist Party. Rosa Luxemburg could speak Russian beautifully, knew Russian literature profoundly, followed Russian political life day by day, was joined by close ties to the Russian revolutionaries and painstakingly elucidated the revolutionary steps of the Russian proletariat in the German press. In her second homeland, Germany, Rosa Luxemburg with her characteristic talent, mastered to perfection not only the German language but also a total understanding of German political life and occupied one of the most prominent places in the old Bebelite Social-Democratic party. There she constantly remained on the extreme left wing.

In 1905 Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg in the most genuine sense of the word lived through the events of the Russian revolution. In 1905 Rosa Luxemburg left Berlin for Warsaw, not as a Pole but as a revolutionary. Released from the citadel of Warsaw on bail she arrived illegally in Petrograd in 1906, where, under an assumed name, she visited several of her friends in prison. Returning to Berlin she redoubled the struggle against opportunism opposing it with the path and methods of the Russian revolution.

Together with Rosa we have lived through the greatest misfortune which has broken on the working class. I am speaking of the shameful bankruptcy of the Second International in August 1914. Together with her we raised the banner of the Third International. And now, comrades, in the work which we are carrying out day in and day out we remain true to the behests of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. If we build here in the still cold and hungry Petrograd the edifice of the socialist state, we are acting in the spirit of Liebknecht and Luxemburg; if our army advances on the front, it is defending with blood the behests of Liebknecht and Luxemburg. How bitter it is that it could not defend them too!

In Germany there is no Red Army as the power there is still in enemy hands. We now have an army and it is growing and becoming stronger. And in anticipation of when the army of the German proletariat will close its ranks under the banner of Karl and Rosa, each of us will consider it his duty to draw to the attention of our Red Army, who Liebknecht and Luxemburg were, what they died for and why their memory must remain sacred for every Red soldier and for every worker and peasant.

The blow inflicted on us is unbearably heavy. Yet we look ahead not only with hope but also with certainty. Despite the fact that in Germany today there flows a tide of reaction we do not for a minute lose our confidence that there, red October is nigh. The great fighters have not perished in vain. Their death will be avenged. Their shades will receive their due. In addressing their dear shades we can say: “Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, you are no longer in the circle of the living but you are present amongst us; we sense your mighty spirit; we will fight under your banner; our fighting ranks shall be covered by your moral grandeur! And each of us swears if the hour comes, and if the revolution demands, to perish without trembling under the same banner as under which you perished, friends and comrades-in-arms, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht!”

-- Leon Trotsky, “On Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg” 1919

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The rise and fall of the Weimar Republic

youtube

The fall of the German empire

THE FIRST REVOLUTION 'from above' - October 1918

Germany became a parliamentary monarchy (2 Oct) with Prince Max of Baden as Chancellor - an attempt to preserve the monarchy.

Germany STRUGGLED and were desperate for peace - the average German survived on only 1000 calories daily in the last months of 1918, 2m soldiers had died in the war, 5m soldiers were wounded or disabled.

THE SECOND REVOLUTION 'from below' - November 1918

Economic struggles led to political upheaval.

Began with the naval mutiny in Kiell 28 Oct 1918 where the sailors refused to leave port for a final attack on the British navy, took control of the harbour and raised the communist flag on their ships.

Workers' and soldiers' councils were established and strikes, mutinies and left-wing uprisings followed. Prince Max of Baden was unable to restore order. The SPD began to fear that further uprisings would leave Germany vulnerable to invasion by its enemies. Kaiser Wilhelm II refused to abdicate in favour of one of his sons and so on 9 Nov, Philipp Scheidemann (an SPD leader) proclaimed the end of the monarchy and the establishment of the Weimar republic from from the Reichstag building. Prince Max announced the Kaiser's abdication (without Wilhelm's agreement) and transferred political authority to Friedrich Ebert, making the new political regime seem more formal and legitimate.

Initial challenges (1918-1923)

- a period of instability and crisis during which the republic was struggling to survive.

POLITICAL ISSUES

The parliamentary system of the Weimar constitution had weaknesses. It was based on a system of proportional representation so that all political parties would have fair representation. HOWEVER, there were so many different groups that no party could win a majority, making coalitions inevitable - these were unstable and ineffective, making them reliant on Presidential emergency powers.

Article 48 - gave the President the power to act without parliament's approval in an emergency, but since 'emergency' was not clearly defined, the power was overused and German confidence in democracy was weakened.

SOCIO-POLITICAL ISSUES

The Spartacist uprising (Jan 1919): Communists, led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, tried to seize power. The spartacists were defeated when the government accepted the help of the Freikorps (independent regiments raised by anti-communist ex-army officers). The Freikorps brutally crushed the uprising and clubbed Liebknecht and Luxemburg to death. A sign of government weakness that that it had to depend on private forces. Later, in March, the remaining German communists attempted another takeover that was also crushed by the Freikorps and army.

The Kapp Putsch (March 1920): The government began disbanding some Freikorps units in accordance with the Treaty of Versailles. They refused and declared a new government with Wolfgang Kapp as Chancellour. The Weimar government was forced to withdraw to Dresden. The army refused to crush the putsch, the army commander saying 'troops do not fire on troops'. The Weimar government called on the workers of Berlin to begin a strike, which paralysed the capital - transport, power and water supplies were cut off. The putsch collapsed within four days.

A series of political assassinations: mainly carried out by ex-Freikorps members, victims of which include the Jewish Foreign Minister Rathenau and the leader of the armistice delegation Erzberger. Due to right-wing parties' sympathy with the criminals and the tendency of anti-Weimar sentiments in the legal professions, the criminals were let off lightly and the government was powerless to do anything about it.

Throughout Germany, the legal and teaching professions, the civil service and the Reicswehr (army) tended to be anti-Weimar, which was a crippling handicap for the republic.

In the following election, there was a move away from the moderate centre-left parties( that had previously dominated the republic) to extreme groups - left and right. The SPD was forced to form a coalition with the righ-wing German People's party (DVP) and the German democratic party (DDP).

Eight changes of government in the following four years made people lose confidence in the government as well as leaving it vulnerable to attacks from political opponents.

The Beer Hall Putsch (1923): A failed coup d'etat by the Nazi party leader Adolf Hitler, the SA and General Ludendorff in Munich, Bavaria. 2000 members of the SA marched through Munic, copying Mussolini's march on Rome. The police easily broke up Hitler's march and the putsch fizzled out. Hitler was sentenced to five years in prison but only served for nine months (Bavarian sympathy for his aims). The putsch was badly planned and executed. The nazi party was banned, but it succeeded in bringing Nazi ideology to national attention.

Hitler's trial: worked wonders for Nazi propaganda. He moderated his tone and centered his defence on his selfless devotion to the good of the people and the need for bold action to save them. His speech was extensively covered in the newspapers the next day.

David King: "The trial [only] covered Hitler's high treason, and so crimes like attacking the Jews, or storming the [Jewish] printing press just didn't get coverage in the trial."

Even if some liberal media condemned the trial as a grace miscarriage of justice, the sensational headlines and extensive coverage the trial received gave Hitler a much larger and more promintent audience than he had ever known.

ECONOMIC ISSUES

In 1919, Germany was close to bankruptcy due to the enormous cost of the war - lasted longer than anticipated - a war of attrition. The link between paper money and gold reserves was abandoned to put more money into circulation. The mark was worth less than 20% of its prewar value.

The coal mines of the Saar were passed to the League of Nations to be run for the benefit of the French for 15 years, and Germany had to supply free coal to France, Belgium and Italy. 90% of the German merchant fleet was surrendered to the Allies. Russian reparations ended.

The Reparations: a total of 132 billion gold mark - 2 billion marks paid every year and 26% of the value of any goods Germany exported.

Were the economic problems and the hyperinflation that developed in 1923 mainly caused by unrealistic reparations demands?

Louis Snyder: reparations were a main reason for Germany's economic crisis.

Geoff Layton: the crisis was caused by long-term inefficiencies in the German economy, which were made worse by reparations.

The Ruhr Invasion: the French concluded in January 1923 that Germany had deliberately defaulted on the coal deliveries it was required to make to France and Belgium. Two days later, French and Belgian troops moved into the Ruhr to seize goods from factories and mines as payment. The German government ordered the workers to follow a policy of passive resistance since Germany was unable to fight back. The German workers, with the promise of strike payments, refused to cooperate with the French. Paramilitaries blew up railways, sank barges and destroyed bridges. The French failed in their aim.

To meet the demand for strike pay, the government printed more money. The German economy had catastrophic levels of inflation as a result, and due to shortages of goods and the worthlessness of money, it became a barter economy.

Marks required in exchange for £1:

November 1918: 20

February 1922: 1,000

November 1923: 21,000,000,000

"Golden Era" under Stresemann (1924-1929)

ECONOMICS

Called off the passive resistance in the Ruhr, reduced government expenditure and promised to start making reparations payments again.

In November 1923, the Rentenmark (one rentenmark = 1 trillion gold marks) was introduced as a temporary currency. The financial situation stabilised.

The working classes had been badly hit as their wages failed to keep pace with inflation. The middle classes and small capitalists lost their savings - many looked towards the Nazis for improvement. Landowners and industrialists, however, came out of the crisis well as they still owned their material wealth, which strengthened their control of big business over the German economy.

Some historians: The inflation was deliberately engineered by wealthy capitalists to gain greater control over the economy. - impossible to prove.

The Dawes plan: provided an immediate loan of 800 million mark from the USA. Relaxed the fixed reparations payments - Germany could pay what it could afford - and no actions would be taken in the event of non-payment without consultation. Reichsmark, backed up by gold reserves, replaced the rentenmark.

Bitterly opposed by right-wing (DNVP & Nazis...) groups that wanted Germany to stop paying reparations altogether.

The French withdrew from the Ruhr in 1924 and relations between France and Germany improved as Germany began payments again.

Industry:

In 1923, industrial output had reached prewar levels, but from 1924, the economy grew rapidly, exports increasing by 40% between 1925 and 1929. Production became more efficient as old machinery was replaced by new.

Inflation rate dropped to almost sero from 1924. Real wages began to increase and living standards imrpoved. Improved infrastructure built with foreign capital.

SOCIAL

New welfare schemes were developed in keeping with the Weimar constitution.

The Public Assistance Programme 1924

The Accident Insurance Programme reformed 1925

The National Unemployment Insurance Programme 1927: extended social insurance to provide relief payments to 17 million workers.

Welfare measures helped raise the standards of living for factory and industrial workers.

Effect?

By the end of the 1920s, there were signs that the economy was slowing down. 1926: balance of trade moved into deficit.

Kurt Borchordt: Germany was living beyond its means. Government spending to compensate those who had lost savings under the hyperinflation, placed a burden on state finances, as well as keeping taxes high. Blames working-class greed for the 'sick economy'

Carl-Ludwig Holtfrerich: much of the responsibility lay with the industrialists, whose cartels reduced healthy competition and who relied on government subsidies rather than reinvesting their profits.

The prosperity did not extend to everyone - farming communities, rural areas. By 1927 and 1928, farmers were seeing little return on the cost of running their farms, but still faced high tax demands, rents or interest payments on mortgages. The wealthy middle- and upper-class were also taxed heavily for government revenue to support the welfare systems.

THE GOLDEN AGE OF CULTURE

Through the 1920s, there was a wave of new cultural achievements.

Bauhaus architectural movement: functional architecture that shunned embellishment. Made use of geometric shapes and focused on affordability, practicality and consistency with mass production, in addition to combining the crafts and fine arts.

FOREIGN POLICY

The Treaty of Locarno 1925: Confirmed Germany's acceptance of its western borders. All countries decided to renounce the use of invasion and force, except in self-defence - prevented another Ruhr invasion.

Improved relations between European countries up until 1930. The spirit of Locarno: the belief that there would be peaceful settlements to any disputes in the future.

Gernaby became a permanent member of the League of Nations in 1926. However, Stresemann used LoN as a platform to air German grievances: ethnic Germans living under foreign rule, the failure of other nations to disarm....

The Treaty of Berlin 1926: reassured the USSR of Germany's commitment to good relations. Helped Stresemann win the trust of the army.

Kellogg-Briand Pact 1928: 62 countries signed the agreement that committed its signatories to settling disputes between them peacefully.

The Young Plan 1929: Stresemann persuaded the USA to re-examine the reparations issue. Reduced the total reparations sum from 132 billion marks to 37 billion marks. Included a 59-year payback period, the end of Allied supervision of German banking, and provision of any disputes to be settled at the International Court of Justice.

The right wing objected (again) to Germany paying any reparations at all, even the reduced sum agreed by the Young plan. DNVP and Nazi party.

LONG-TERM AIMS OF STRESEMANN: Revision of The Treaty of Versailles.

Perspectives on Stresemann:

Jonathan Wright: Stresemann=a hypocrite who secured European trust, US money and protection from French invasion, in order to leave open the opportunity for a revision of Germany's eastern borders.

A.J.Nicholls: "It is unlikely that the French or British politicians really imagined Stresemann had changed [from his nationalist views]. They knew the German foreign minister was a tough negotiatior, well able to defend the interests of his country."

POLITICAL STABILITY 1924-1929

Political developments: much greater political stability. More than 50% of people voted for republican parties in May 1924, rising to 60% in a second election in December 1924.

The republican vote increased:

May 1924: more than 50% December: nearly 60%

The extremist vote declined:

Nazis: May 1924: 6.5% December 1924: 3%

KPD: May 1924: 12.6% December 1924: 9%

Greater cooperation amongst parties: DNVP with the republicans.

The election of Paul von Hindenburg, a respected conservative monarchist, as president encouraged the poltical right to accept the republic.

HOWEVER, the coalitions were fragile.

The Crisis Years and The Rise of Hitler

The Crisis Years:

The prosperity under Stresemann was much more dependent on US loans than most people realised. When the USA, due to theWall Street Crash oct 1929, was forced to stop the loans and began to call in many short-term loans already made to Germany. This caused a crisis of confidence in the currency and led to a run on the banks, many of which had to close. The industrial boom had led to worldwide over-production, but now exports were severely reduced, resulting in the closing of factories, and ultimately unemployment. Mid-1931: Unemployment nearly 4 million. By this point, Stresemann had died of a heart attack.

The government of Chancellor Brunning (CCP) reduced government spending, introduced high tariffs to help German farmers, and bought shares in factories hit by the slump. HOWEVER, these measures were not efficient enough. Unemployment continued to rise. Spring 1932: 6 million unemployed. The government was criticised by almost all of society, especially industrialists and the working class who demanded more decisive action. The republic lost much of the working-class support because of the increasing unemployment and reduction in unemployment benefits.

0 notes

Photo

“Virtual Martial Law Decided on By German Cabinet,” Kingston Whig-Standard. February 28, 1933. Page 1.

----

Communists to Be Outlawed in Next Reichstag

----

German Government's Fist to Descend Heavily Upon Enemies to Nation - Further Acts of Terrorism.

---

FIRE IN REICHSTAG

----

Elections to Be Held Sunday and Hitler's Party Is Assured of Control by Outlawing Communists.

---

BERLIN, Feb. 28 - Virtual martial law under police regime was decided upon by the German Cabinet today.

The Cabinet, which had been in session since 11.00 am, adjourned at 2.30 pm. until 5.00 pm. It had heard a report from Wilhelm Goering, Minister without Portfolio, upon the fire which damaged the Reichstag building yesterday and the result of a raid last week by police on Karl Liebknecht House. Communist headquarters on Buelowplatz.

A military state of emergency was refrained from in order to keep the Reichswehr (standing army) out of political action, but the measures to be decreed will have the effect of placing Germany under a state of emergency with the sole object of meeting Communist danger.

Goering Reports

Herr Goering reported that material found in Karl Liebknecht house include the forged orders to the police and to Nazi storm troopers and even included instructions for poisoning welts for food.

According to the testimony of two men who were arrested, they telephoned yesterday evening to the Socialist organ Vorwarts at the request of this paper that Herr Goering had himself arranged for the Reichstag fire.

Giving assurance "the Government's fist will descend heavily upon the Communists, Chancellor Hitler inspecting the Reichstag building, told a correspondent of the Voelkische Beobachter, the Chancellors newspaper:

‘‘Here you see what Communism has in store for Germany and for Europe. This deed was dictated by Communists by sinister spirit."

The fire brigade was still pouring water on the smouldering ruins of the building which cost $5,000,000 to construct.

Farther Terrorism

The Communists Goering said were prepared for further acts of terrorism some of which would be committed by men In the uniforms of police the steel helmet organization and the Nazis.

The Minister further Informed the press that elections for the Reichstag and the Prussian Diet would be held next Sunday under all circumstances.

According to one press liaison officer, the Communist votes in the next Reichstag simply will not be counted at they will be considered non-German.

The Government estimates that a year will elapse before the Reichstag building can be occupied.

Among 110 persons arrested by noon were two leading members of the Pacifistic League for Human Rights and several radical writers.

Ernst Torgler, Communist floor leader of the Reichstag, voluntarily presented himself to police.

Outlawing of only the Communists was expected easily to assure Chancellor Hitler's party of control in both the Reichstag and Diet to be elected Sunday.

#reichstag#reichstag fire#enabling act#nazi seizure of power#crisis of the weimar republic#nazi germany#kommunistiche partei deutschlands#suppression of political dissidents#martial law

0 notes

Quote

'Sie überschätzen die Amerikaner', bemerkte mir soeben ein seit langem in der neuen Welt ansässiger Landsmann, 'die Amerikaner sind entsetzlich bornierte Menschen, stockkonservativ.' Der gute Landsmann - und das suchte ich ihm begreilich zu machen, jedoch ohne Erfolg - hat sich in Worte und Vorurtheile verrannt. 'Stockkonservativ' sind die Amerikaner allerdings in politischer Hinsicht - aber das ist keine Borniertheit, sondern hat einen sehr guten Grund. Alle demokratischen Völker sind konservativ. Die amerikanische Verfassung verdient es wahrhaftig, 'konserviert' zu werden – trotz alledem und alledem. Despotisch regierte Völker sind niemals konservativ, weil sie nicht zufrieden sind. Nur demokratische Völker können konservativ sein – eine verteufelt einfache Wahrheit, die aber von so vielen sogenannten Staatsmännern noch nicht kapiert worden ist.

Wilhelm Liebknecht (1887)

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Karl Marx's greatest friend and colleague [Friedrich Engels] has just called him the best-hated man of this century. That is true. He was the best-hated but he was also the best-loved. The best-hated by the oppressors and exploiters of the people, the best-loved by the oppressed and exploited, as far as they are conscious of their position. The oppressed and exploited people love him because he loved them. For the deceased whose loss we are mourning was great in his love as in his hatred. His hatred had love as its source. He was a great heart as he was a great mind. All who knew him know that.

Wilhelm Liebknecht, Speech at Karl Marx’s Funeral (1883)

#Wilhelm Liebknecht#Karl Marx#Friedrich Engels#hate#love#class struggle#working class#socialism#communism#revolution

30 notes

·

View notes

Quote

You say Vollmar is not a traitor. Maybe. Nor do I think he views himself as such. But what would you call a man who asks of a proletarian party that it should oblige the Upper Bavarian big and middle peasants, owners of anything between ten and thirty hectares, by perpetuating a state of affairs based on the exploitation of farm servants and day laborers? A proletarian party, expressly founded for the perpetuation of wage slavery! The man may be an anti-Semite, a bourgeois democrat, a Bavarian particularist and anything else you care to name, but a Social Democrat?

Friedrich Engels shitting on German reformist socialist Georg von Vollmar in a letter to Wilhelm Liebknecht, November 24, 1894.

#Marxism#Engels#Liebknecht#Vollmar#German Social Democracy#Bavarian particularism#anti-Semitism#peasantry#reformism#opportunism#bourgeois democracy#socialism#communism

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Karl Marx was a fencer.

There’s not a lack of mentions of this online however they seem to point to three major sources:

“Karl Marx and the Birth of Modern Society: The Life of Marx and the Development of His Work” by Michael Heinrich with an excerpt here

“By the Sword: Gladiators, musketeers, samurai warriors, swashbucklers and Olympians” by Richard Cohen.T with an excerpt here.

There’s more detail within those links and the following however the main bit noted in the memoirs of Wilhelm Liebknecht 1896 (a friend of Karl Marx) which seems to be the original source goes as follows:

“ A short while after my arrival, a Parisian labourer came to London, in whom not only the French colony was deeply interested, but all of us fugitives as well, and most likely also our “shadow”: the international police. It was Barthelemy, about whose escape from the Conciergerie, accomplished by him with admirable adroitness and daring, we had heard already through the papers.

...

I fenced frequently with him, I mean in reality. The Frenchmen had opened a “fencing salon” in Rathbone Place, on Oxford street, where fencing with sabres, swords and foils and pistol shooting could be practiced. Marx also came now and then and lustily gave battle to the Frenchmen. What he lacked in science, he tried to make up in aggressiveness. And unless you were cool, he could really startle you. The sabre is used by the Frenchmen not alone for cutting, but also for thrusting, and that inconveniences a German a little at first. But one soon becomes accustomed to it. “

The first source also goes into a bit of detail about the possibility of Marx participating in a duel, and while it’s not impossible there doesn’t seem to be much proof of him fighting in one, but if he did he seems to have come out ininjured.

So seems in line with Meyer’s notes on Germans avoiding thrusting.

Also the above would definitely fit Marx into the first type of fencers as according to Meyer.

Secondly it seems the french fencer and revolutionary who taught Marx fencing found Karl to be too conservative. Folks sometimes claim that if you’re not left of Karl Marx it’s not enough nowadays but if anything it seems historically being Karl Marx was not left enough.

Also if you want to learn more about using sabers as Karl Marx did you may want to check out the various saber manuals noted in the treatise database here under the 19th century french ones. But do keep in mind that these are not necessarily the exact same system that he studied,merely that those before the 1850′s have a solid chance of being quite similar in many aspects.

It’s pure conjecture but Emmanuel Barthélemy may even have used a system similar to that of Jean-Louis Michel, claimed to be The Best Swordsman in Napoleons Army of which you can read a translation by P.T.Crawley here since the timelines are roughly similar and that Jean Louis was quite influential towards the french school of fencing(albeit it’s a question of when and where Barthélemy learned fencing himself).

And to learn more about using such a weapon generally check out Military and Classical Sabre

P.S. Happy birthday commie grandpa, fencers of the world unite.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m reading Markus Wolf’s memoirs and I absolutely love his description of growing up in Moscow but also that rapid shift in tone omfg

We adjusted slowly to a strange language and culture, fearful of the harsh manners of the children who shared our courtyard. “Nemets, perets, kolbassa, kislaya kapusta,” they would shout after us: “Germans—pepper, sausage, sauerkraut.” They laughed at our short trousers, too, and we begged our mother for long ones. Finally she gave in with a sigh, saying, “You’re proper little men now.”

But we were soon fascinated by our new environment. After our provincial German childhood, the bustling city, with its rough and ready ways, thrilled us. In those days people still spat the husks of their sunflower seeds onto the pavement, and horse-drawn traps clattered through the street. Moscow was still a “big village,” a city with peasant ways. At first we attended the German Karl Liebknecht School (a school for children of German-speaking parents, named after the Socialist leader of the January 1919 Spartacist uprising, who was murdered in Berlin shortly thereafter), then later, a Russian high school. By the time we became teenagers we were barely distinguishable from our native schoolmates, for we spoke their colloquial Russian with Moscow accents. We had two special friends in George and Victor Fischer, sons of the American journalist Louis Fischer. It was they who gave me the nickname “Mischa,” which has stuck ever since. My brother Koni, anxious not to be left out, took the

Russian diminutive “Kolya.”

The Moscow of the thirties remains in my memory as an era of light and shadow. The city changed before our eyes. By now I was a rather serious teenage boy and no longer thought of Stalin as a magician. But as the new multistory apartment blocks soon appeared around the Kremlin, and the amount of traffic suddenly increased as black sedans replaced the pony traps, it was as if someone had waved a powerful wand and turned the Moscow of the past into a futuristic landscape. The elegant metro, with its Art Deco lamps and giddyingly steep escalators, hummed into life, and we would spend the afternoons after school exploring its vaults, which echoed like a vast underground church. The disastrous food shortage of the twenties abated, but despite the new buildings, my family’s friends, mainly Russian intellectuals, lived cheek by jowl in tiny apartments. There were spectacular May Day parades. The exciting news of the day carried highlights of the age like the daring recovery of the Chelyushkin expedition from the pack ice of the Arctic Ocean after its conquest of the North Pole. We followed these events with the enthusiasm that Western children devoted to their favorite football or baseball teams.

With similar passion Koni and I both joined the Soviet Young Pioneers— the Communist equivalent o f the Boy Scouts—and learned battle songs about the class struggle and the Motherland. As Young Pioneers we marched in the great November display on Red Square commemorating the Soviet revolution, shouting slogans of praise for the tiny figure in an overcoat on the balustrade above Lenin’s tomb. We spent our weekends in the countryside around Moscow, gathering berries and mushrooms because even as a city dweller our father was determined to preserve his nature worship as a way of life. I still missed German delicacies, though, and found the sparse Soviet diet, with its mainstays of buckwheat porridge and sour yogurt, desperately boring. Since then I have learned to love Russian food in all its variety, and if must say so, I make the best Pelmeni dumplings (stuffed with forcemeat) this side of Siberia. But I have never developed a great fondness for buckwheat porridge, probably as a result of having consumed tons of the stuff in my teens.

In summer I was dispatched to Pioneer camp and elevated to the role of leader. I wrote to my father complaining about the miserable gruel and military discipline that prevailed there. Back came a typically optimistic letter, bidding me to resist the regime by forming a commission with my fellow children. “Tell them that Comrade Stalin and the Party do not condone such waste. Quality is what counts.. . . Under no circumstances must you, as a good Pioneer and especially as a Pioneer leader, quarrel! You and the other group leaders should speak collectively with the administration. . . Don’t be despondent, my boy.”

The Soviet Union was now our only home, and on my sixteenth birthday, in 1939, I received my first Soviet papers. Father wrote to me from Paris, “Now you are a real citizen of the Soviet people,” which made me glow with pride. But as I grew older I realized that my father’s infectious utopianism was not my natural leaning. I was of a more pragmatic temperament. Of course, it was an exhilarating time, but it was also the era of the purges, in which men who had been feted as heroes of the Revolution were wildly accused of crimes and often condemned to death or to imprisonment in the Arctic camps. The net cast by the NKVD—the secret police and precursor of the KGB—closed in on our emigre friends and acquaintances. It was confusing, obscure, and inexplicable to us youngsters, schooled in the tradition of belief in the Soviet Union as the beacon of progress and humanitarianism.

But children are sensitive to silences and evasions, and we were subliminally aware that we were not party to the whole truth about our surroundings. Many of our teachers disappeared during the purges of 1936-38. Our special German school was closed. We children noticed that adults never spoke of people who had “disappeared” in front of their families, and we automatically began to respect this bizarre courtesy ourselves.Not until years later would we face up to the extent and horror of the crimes and Stalin’s personal responsibility for them. Back then, he was a leader, a father figure, his square-jawed, mustached face staring out like that of a visionary from the portrait on our schoolroom wall. The man and his works were beyond reproach, beyond question for us. In 1937, when the murder machine was running at its most terrifyingly efficient, one of our family’s acquaintances, Wilhelm Wloch, who had risked his life working for the Comintern in the underground in Germany and abroad, was arrested. His last words to his wife were “Comrade Stalin knows nothing of this.”

Of course, our parents tried to keep from us their fears about the bloodletting. In their hearts and minds, the Soviet Union remained, through all their doubts and disappointments, “the first socialist country” they had so proudly told us about after their first visit in 1931.

My father, I now know, was fearful for his own life. Although his wife and children had been granted Soviet citizenship because we lived there, he spent much of his time abroad and so was not a citizen. He was, however, still able to travel on his German passport, even though his citizenship had been revoked. He had already applied for permission from the Soviet authorities to leave Moscow for Spain, where he wanted to serve as a doctor in the International Brigades fighting against General Franco’s Fascists in the bitter Civil War there. Spain was the arena where the Nazi military tried out its deadly potential, practicing for its later aggression against other vulnerable powers. Throughout Europe, left-wing volunteers were flooding to the aid of the Republicans against the Spanish military insurgents. For many in the Soviet Union, fighting there also meant a ticket out of the Soviet Union and away from the oppressive atmosphere of the purges. Decades later, a reliable friend of the family told me that my father had said of his attempts to reach Spain: “I’m not going to wait around here until they arrest me.” That revelation wounded me, even as a grown man, for it made me realize how many worries and reservations had been hidden from us children by our parents in the thirties, and how much sorrow must have been quietly harvested around us among many of our friends in Moscow.

My father never did reach Spain. For a year, his application for an exit visa lay unanswered. More and more of our friends and acquaintances in the German community had disappeared and my parents could no longer hide their anguish. When the doorbell rang unexpectedly one night, my usually calm father leapt to his feet and let out a violent curse. When it emerged that the visitor was only a neighbor intent on borrowing something, he regained his savoir-faire, but his hands trembled for a good half hour.

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day, 5 May 1818, Karl Marx was born in Trier, Germany. Living until the age of 64, Marx was a journalist, revolutionary socialist, philosopher and economist, and one of the most influential figures in world history. Like all of us, he had his flaws, but he dedicated his life to the the cause of the working class, and inspired hundreds of millions with his works, including Capital. Over a century later, Capital remains the most incisive critique of the capitalist system. While his ideas have been used by some to justify politicians and parties acting on behalf of the working class, Marx was clear that ultimately "The emancipation of the working class must be the work of the working class itself." Though his wife was from a wealthy background, Marx and his family often lived in abject poverty, and four of their children died in infancy. His children who survived to adulthood all became socialist activists in their own right, including his eldest daughter Jenny who also died before him. Despite his often difficult circumstances and the tragedy in his personal life, Marx was also well up for a laugh. For example his friend and biographer Wilhelm Liebknecht recounted an evening pub crawl in west London where, forced into a tactical retreat after drunkenly slagging off a bunch of English people, Marx and his friends began smashing street lamps by throwing stones at them, until being spotted by a policeman, whereupon they had to flee down back streets and alleyways. In the Communist Manifesto he co-wrote with Friedrich Engels, Marx noted that "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles." This is something we hope to illustrate at Working Class History. You can get a modern edition of the manifesto with an introduction by Eric Hobsbawm, as well as other related works, here: https://shop.workingclasshistory.com/collections/books/karl-marx https://www.facebook.com/workingclasshistory/photos/a.1819457841572691/1980089092176231/?type=3

675 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy birthday, Wilhelm Liebknecht! (March 29, 1826)

A founding member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany and colleague of Karl Marx, Wilhelm Liebknecht was a leading figure in the early days of the socialist movement. Born in Hesse, Liebknecht gained an interest in communism during his studies, reading the works of French theorist Henri de Saint-Simon. In 1848, as unrest swept Europe, Liebknecht became active in the revolution in Germany, fleeing to Switzerland when the revolt was crushed. There, he became acquainted with Friedrich Engels and, after journeying to London, Karl Marx. In 1862, he returned to Germany and became associated with Ferdinand Lassalle and his General German Workers’ Confederation, the precursor to the SPD. He was elected to the legislature, but often found himself in legal trouble or imprisoned for his socialist beliefs. The socialist and workers’ parties would ultimately unite, with Liebknecht as a leading member, as the SPD in 1890, taking 20% of the vote in the 1890 German federal election. Liebknecht would die in 1900 while his son, Karl, would also play a prominent role in German socialist politics, helping to lay the groundwork for the formation of the Communist Party of Germany and helping to lead an abortive revolution in the wake of World War I.

“Capital does not participate where no profit can be made. Humanity is not quoted on the stock exchange.”

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg Murdered

Rosa Luxemburg in 1915.

January 15 1919, Berlin--After the end of “Spartacist Week”, its leaders were now on the run. An “Association for Combating Bolshevism” (supposedly founded by Russian emigrés) offered bounties for their capture. Rosa Luxemburg (who had not even been in favor of the week’s events), Karl Liebknecht, and Wilhelm Pieck, all Spartacist (now Communist) leaders, moved their hiding place on the night of the 14th. Unfortunately for them, they moved very close to a cavalry division headquarters, and they were quickly handed over to the soldiers the next afternoon. Pieck somehow managed to escape, and later became the President of East Germany after the next war. Luxemburg and Liebknecht, however, were killed that night. A certain Private Runge clubbed them both on their heads with his rifle (likely killing Luxemburg). Liebknecht was taken to the Tiergarten and shot “while attempting to escape.” Luxemburg was shot in the head several times before her body was dumped in the Landwehr Canal; it would not be found until May. Private Runge was convicted of “leaving his post without being properly relieved” and of “improper use of his weapons.”

Sources include: Gregor Dallas, 1918: War and Peace.

#wwi#ww1#ww1 history#ww1 centenary#world war 1#world war i#world war one#The First World War#The Great War#Berlin#Spartacists#january 1919

49 notes

·

View notes