#what if you were a depressed divorcee with a dead end job and a drinking problem and somehow through a convoluted series of events

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

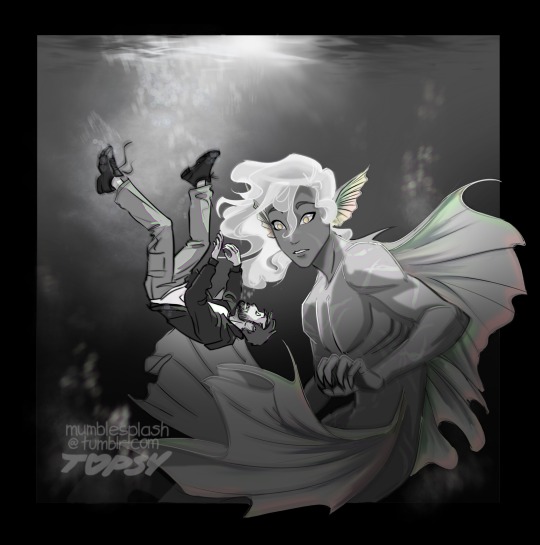

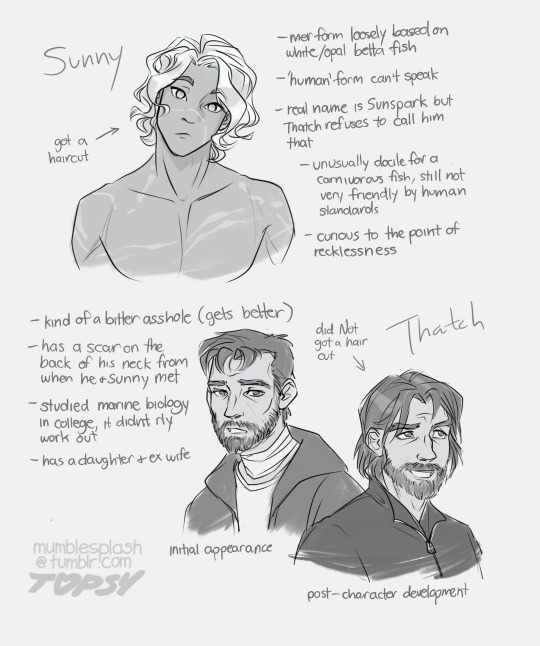

thought about the expression “big fish in a small pond” too hard and accidentally invented new ocs

#my art#this whole story is extremely self indulgent in a very specific way i don’t think i could explain if i tried#don’t worry about it i’ve just been taken by the madness again#what if you were a depressed divorcee with a dead end job and a drinking problem and somehow through a convoluted series of events#all of these issues were resolved because one day you fell and almost drowned in the ocean#what if you escaped a watery grave in the depths of the uncaring sea because one tiny part of it noticed you#what if you met someone who was better than you in all the ways you thought you cared about#but also had comically exaggerated versions of all your flaws#and it made you realize getting everything you want wouldn’t fix you#and also. and this is very important. what if there was a mermaid and he was so so pretty and sparkly :)#do you see. do you understand the vision here

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey.

steve harrington x reader

summary: he was such a staple piece in your life, that as a child and young teen, you never saw your life without him. late night promises and pinky swears were made in blanket forts that you two would be friends until the day the sun burned out in the sky. it was just a given that’d he be there, that you never worried about the two of you drifting apart or being separated. he promised he’d always be there, and you had believed him. you now corrected yourself, foolishly believed him.

word count: 3.4k

chapter: i / ii / iv / v / vi / vii / viii

chapter iii

You thanked the universe it was Saturday. This not only meant you had today and tomorrow to recover from the night before, but your mom always went out on Friday nights and slept most of Saturdays away. It wasn’t that you were afraid of getting in trouble, you just didn’t want the interrogation she would give you if she saw you walking in with a boy’s clothes on and your own clothes, wet, in your arms. To your dismay, the second you walked through the door, your mother was sitting at the kitchen table with a cigarette and her morning coffee.

“Look who’s back early.” Your mother in a cheerfully knowing voice.

“I could say the same to you.”

“Ha ha.” She spoke and rolled her eyes.

You went to the table and joined her.

“Coffee?” She asked as she slide her pack of cigarettes towards you.

“Hot chocolate. I’m not planning on staying awake much longer.” You replied and lit yourself a cigarette, throwing your wet clothes on the chair next to you.

Your mother smiled and nodded, getting up to make your drink.

You and your mother had a different relationship. When your father and she had split (after she had found him wrapped in the throws of passion with his assistant in their marital bed) she had kind of fallen apart for a while. All of her friends had forsaken her for being a divorcee, including Steve’s parents, you were all she had left. You took care of her while she had depressive episodes and you were the one who cooked, cleaned and took care of everything for most of your freshman year. After that, your mom got her life back. Got a better job, and started to look like herself again. But after all of that, things never went back to a traditional mother-daughter relationship. It became like two old ladies living under the same roof. She still parented you on occasion, but really, you stayed out of trouble, did well in school and never gave her a reason to really discipline you. So, the dynamic never changed. You liked it this way. It was easy, you both came and went and supported each other. You both were a little broken, but it was okay. You loved each other and that’s all that mattered.

“Here.” Your mother placed the mug of hot chocolate in front of you.

“Thanks.” You smiled and took a small sip of the hot liquid.

“So, can I ask why you’re carrying a pile of wet clothes and wearing some that definitely aren’t yours?” She quirked an eyebrow at you while sliding the ash tray so it would be close enough for the both of you to use it.

“If you must.” You sighed, ashing your cigarette.

“So…?”

“I went to a party, where I happen to run into Steve,”

“Harrington?” She asked engaged.

“Yes, Harrington,” You continued, “Him and Nancy broke up and I don’t know, I guess old feelings die hard, so I went back to his place and we talked. Swam, fell asleep. Don’t worry no funny business, scouts honor.” You put your pointer and middle finger to your temple in a faux solute.

“Did he drive you home?”

“No. I walked.”

“What?!” She exclaimed and placed her cup down.

“Sweetheart, you could have caught your death out there! You could have called me.”

“Eh, didn’t want to bother you.” You shrugged.

She gave you a You-Know-You-Could-Never-Bother-Me- look and you smiled back.

“You should have made him drive you home, (Y/N).”

“I left before he woke up.” You fiddled with the lip of your mug.

“Why?” Your mother asked.

“Freaked out I guess. It was weird being there.”

“Did he apologize for being such an asshole- sorry, jerk to you for so long?”

You laughed at your mom’s correction, “Yeah, kinda. He probably didn’t mean it. Who cares if he did, y’know? Everything will be the same Monday.”

Your mother saw the slight disappointment on your face.

She placed her hand over yours in comfort, “Don’t be so sure. Sometimes people surprise us.”

“Yeah, maybe.” You offered a small smile.

Then the two of you made small talk while you finished your drinks.

“I’m going to lay down. I’m exhausted.” You told your mother while you placed your mug in the sink.

“Okay,”

“Oh!” She said remembering, “Jonathan called last night, wanted to make sure you got home alright. I told him you were here and safe.”

“What if I had been kidnapped mother! Weren’t you worried in the slightest?” You said dramatically, feigning hurt.

“Eh, they would have brought you back to me, I wasn’t worried.” She smiled and shrugged.

You squinted and shook your head with a smile, “Love you too, mother.”

“Love you more!”

After you had woken up from your early morning nap, it was noon and there was a small note folded next to you.

Had to step out, while you were asleep Steve Harrington called. I swear I just told him you were asleep and not to pound sand like I wanted too.

Xoxo,

Mom

You sighed. You were really hoping Steve wouldn’t have called. You hoped he would have woken up too hungover to even remember if you were there the night before or not. Sadly, that wasn’t the case. You made your way down stairs to get some coffee and a muffin while debating whether to call him back or not. You hopped up to sit on the counter to eat your breakfast and picked up the phone that rested on the wall. The long sparling chord brushed your left shin. You stared to dial Steve’s number and a wave of panic hit you again, so you hung up the phone and dialed the Byers’ home instead. They rarely ever answered it since the incidents with Will last year, but every once and a while, Bob, Joyce’s new boyfriend, would be there and answer it out of habit. Today was one of those days.

“Hello, hello?” Bob’s cheerful voice rang through the phone.

“Hi Bob, It’s (Y/N) (Y/L/N).

“Well good afternoon! How may I direct your call, Ms. (Y/L/N).”

“To Jonathan Byers’ office, please.” You said smiling and playing along.

“Oh, I’m sorry, Mr. Byers’ is out at the moment can I take a message?”

“Nah, that’s fine. Just tell him I called?” You asked, a little disappointed Jonathan wasn’t home.

“Of course!” He said.

“Thanks Bob, tell Joyce hi for me, will ya?”

“Always do,” You could hear the smile in his voice.

“Thanks, have a great day.”

And with that both lines were hung up.

You were a little miffed that Jonathan wasn’t home. You wondered if he could have been the one to pick up the pieces of a newly single Nancy Wheeler. But Jonathan was respectful and a gentleman, he’d never try to start their relationship this soon after things had ended so rocky with Steve.

You leaned you head against the wall next to the phone and ate your muffin and drank your coffee in silence. You just let your mind go blank as you continued your mundane activity. That’s why when the phone rang again, you almost fell from the counter.

“Hello?”

“You seriously just left? Really?” It was Steve.

Fuck.

“Sorry, I didn’t feel well and didn’t want to wake you.”

“Bullshit, (Y/N), try again.” His voice was stern.

“Honest! I was just hungover and knew a cold walk would remedy it.”

“Are you fine now then?”

“For the most part.”

“Good, I’m coming to get you.”

“What?” You almost choked on your salvia.

“Yeah, so get dressed.” The line went dead.

You sat on the counter, a little stunned. The last thing you wanted to do was spend the day with Steve, especially after your internal conflict of ‘I love him, I love him not’ you had done on your way home this morning.

But, you found yourself upstairs, hastily wiping away last night’s make up to reapply a fresh layer. You opted for a ponytail for your hair, since you hadn’t had a chance to take a shower and had no clue how close Steve really was to being at your house. After a quick outfit change you smoothed your sweater and looked at yourself in the mirror, you almost changed, but as the thought crossed your mind the doorbell rang.

You walked down the stairs so slow Steve rang the bell again and you sighed. When you opened your front door, there stood Steve Harrington in all of his glory. You cursed yourself at the slight flutter your stomach gave when you first saw him.

“Finally. Now let’s go.” He grabbed your arm and dragged you towards his car.

“Where to, exactly?”

“You’ll see.”

You sat in the front seat of Steve’s car in front of the Dairy Freeze. You had a vanilla shake in your hands and he had a strawberry one, and you both were waiting for your food.

“I forgot how good these shakes are.” Steve said smiling down at his cup.

“Yeah, but know shakes are better when it’s not twenty degrees out.” You said back. It wasn’t supposed to come out as a jab at him, but it had.

“Whatever…” He trailed off.

“Sorry…”

Silence fell over the car again.

“You know,” Steve started, “I like thinking that when we took my dad’s car we parked in this same spot and ate the same things. You have always been a vanilla shake with a chicken sandwich and I’ve always been a strawberry shake and a cheeseburger.”

“Yeah.” You smiled, liking that he remembered your order.

“I’ve been on a date or two here that ended not so good, so this place just doesn’t taste as good as it did when I was a kid.” You sucked at the straw of your shake.

“With who?” Steve’s voice hardened, but you didn’t notice.

“Scott Thompson in the tenth grade then last year with some college guy named Derek, you wouldn’t know him.”

“Scott Thompson? That fucking guy? What did you ever see in him?” Steve was trying to play off his interest as fun banter, but he was secretly making plans to shoulder Thompson extra hard in their next basketball scrimmage.

“I don’t know! He was nice to me. He told me he’d pay for everything but forgot his wallet so I paid. I didn’t care but it was annoying how he kept bringing up that he forgot his wallet. He also put his arm around me and like so awkwardly touched my boob that I told him I had to leave and called my mom from a payphone to pick me up.” You laughed thinking back on it now, it had been mortifying at the time, but now it was a good story.

“And the college guy?” Steve asked a little too quickly.

“I met him here actually. With Jonathan. We were hanging out in his car here and I went in to get more ranch and bumped into him. We exchange numbers went out a few times, but I don’t know he gave me the creeps after our third date so I never called him again. So, I don’t know, I guess because I met him here, this place gives me residual creeps.”

“Did he hurt you?” Steve asked lowly, gripping his drink tightly.

“No! Nothing like that, he was just weird, like he would do and say weird shit that made me feel, well weird.” You chuckled at your lack of vocabulary.

“Well I’m glad you aren’t seeing him anymore if he made you feel like that.” Steve stated.

“Thanks?”

Then the silence was back. The waitress brought you your food so now you both just ate your food and looked around at passing cars and people going in and out of the restaurant. After you were halfway done with your sandwich you placed it aside and asked what you had been wondering since the night before.

“Why me? I mean, why did you call me today? Why not one of your friends?”

“You are my friend.”

“Steve…” You pressed.

“Who could I call, (Y/N)? Tommy? Carol? Oh yeah, they are great people, really want them to console me and make me feel better.” Steve said frustrated as he ran a hand through his hair.

“Aren’t they your friends though?” You asked, honestly wondering.

“Yeah, but I don’t know, not really.” Steve said.

“After I got together with Nancy, I started to see that all those guys, they suck. They’re mean and just assholes. So, I just started to distance myself from them and spend all my time with Nancy.”

“Okay, I get it,” You spoke turning away from Steve, “Now that Nancy’s gone you need someone to fill her shoes.”

“No! (Y/N)! That’s not what I meant, fuck!” Steve said anxiously.

“I can just never say the right thing, can I?” He chuckled sadly to himself.

“You do have a tendency to put your foot in your mouth.”

“Yeah I guess I do.”

Steve meant well, you were sure of it. But you didn’t want to be his consolation prize for losing Nancy. That wasn’t fair to you, not at all.

“Okay, well listen. I’m not going to put my shoe in my mouth-“

“Foot.” You corrected and you saw him smile.

“Okay, yeah. Foot. I’m not going to put my foot in my mouth this time when I say: I really missed you, (Y/N). Like a lot. Last night just reminded me. And right now, I don’t want anyone but you. I’m sad and lost and the only person I want to spend time with is you, okay?” Steve said this with such conviction that your breath caught in your throat.

“Okay.” You whispered.

After the Dairy Freeze, the two of you went back to Steve’s house. You offered to go to yours so he could get his clothes but you told you to keep them. This made you smile just a little but too big. At his house again, you both settled on the couch and flipped channels. Once you saw Audrey Hepburn’s face flash across the screen you yelled.

“Back! Go back!” Steve did so.

“Breakfast at Tiffaney’s? Really?” Steve groaned.

“You know I love this movie.” You said settling back into the couch happily.

“Yeah, but I know I’ve seen this with you at least fifteen times, so God knows how many times you’ve seen it.”

“Classics never get old, Harrington.”

To your pleasure and Steve’s dismay, it was the beginning of the movie. Steve really had seen the movie with you a million times when you were children. Your mother had always wanted you to be a well rounded child, so she had shown you many old movies when you were growing up. Some were better than others, you were still unsure why your mother had had you sit through both Easerhead and Un Chien Andalou in one sitting at the tender age of eleven. Thankfully Steve hadn’t been around for that movie night.

But out of all the old movies you’d seen, you’d always had a soft spot for Breakfast at Tiffany’s. It was the movie you watched whenever you were sick or had an exceptionally tiring day. Steve knew this, and even if this was supposed to be a day of making him feel better, he was fine with you getting the movie choice. Watching you recite lines and add your own commentary was cheering him up.

“We’re friends after all,” Holly said on the TV, “We are friends, aren’t we?”

Without thinking you repeated these lines, and the air became heavy with insinuation.

“Let’s not say another word, let’s just go to sleep.” You muttered in tune with the TV.

“That’s us.”

You looked at Steve with a cocked eyebrow.

“We’re friends, drinking, smoking cigarettes and sleeping next to each other. After all this time we are Holly and Paul.” Steve gestured to the television.

You opened your mouth to reminded him that Holly and Paul fell in love, but you kept it to yourself. Hoping that he forgot that part of the movie or didn’t mean you were like Holly and Paul in that way.

You settled for, “Yeah, I guess we are.”

As the movie drew to a close the sun began to set. You had been so engrossed in it that you hadn’t noticed that Steve had fallen asleep. His mouth open slightly and his forearm over his eyes.

“Holly, I’m in love with you,” Paul spoke.

“So what?” You mouthed along with Holly.

“So what? So plenty. I love you, you belong to me!”

“No,” You and Audrey Hepburn both began, “People don’t belong to people.”

As the scene continued, it began to hit you in a way this movie had never done before.

“You know what's wrong with you, Miss Whoever-you-are? You're chicken, you've got no guts. You're afraid to stick out your chin and say, "Okay, life's a fact, people do fall in love, people do belong to each other, because that's the only chance anybody's got for real happiness." You call yourself a free spirit, a "wild thing," and you're terrified somebody's gonna stick you in a cage. Well baby, you're already in that cage. You built it yourself. And it's not bounded in the west by Tulip, Texas, or in the east by Somali-land. It's wherever you go. Because no matter where you run, you just end up running into yourself.”

Tears filled your eyes as you watched Holly desperately search for her cat while Paul watches, you held your breath.

Moon River filled your ears and as Holly and Paul fall into a passionate, exhausted kiss, and you cried. For the first time since you had first seen the movie, you cried. You did so quietly as to not wake Steve, but as the credits ran in, you felt horrible.

Something about Paul’s speech and the emotional coming together of the two leads was too much to bare. It felt too poignant to your situation. You and Steve were Holly and Paul. But you weren’t in love. Things were different now and you weren’t friends let alone in love. Even if you were in love with him, which the jury of your heart was still out on, he didn’t love you. Not like that, never like that. And love was never real love if it was reciprocated. And you knew it was selfish, but you don’t think you could watch him run back to Nancy on Monday. It was inevitable. They were the two in love. People do fall in love and people do belong to each other, but to your tearful dismay, Steve didn’t belong to you, he never would. But you thought if running back into the arms of Nancy Wheeler and belonging to her again was Steve’s chance at happiness, you wanted him to take it.

You felt embarrassed and overdramatic. Here you were crying over a movie next to a boy you hadn’t really talked to in the last four years. You were crying on this boy’s couch about him while he slept. This thought was mortifying and you hated yourself for this whole scene. Why you had suddenly become so emotional over Steve Harrington was a mystery to you.

“(Y/N)? Are you crying?” Steve asked concerned, sleep still lacing his voice.

You began to quickly wipe away your tears, “Yeah. This movie is sad, that’s all.”

“But Holly realizes she loves Paul. How is that sad?” Steve asked moving towards you.

He had remembered the end of the movie.

“Yeah, well I guess I just still get emotional about it.”

Steve nodded, and pulled you into a hug. You were in no way in any shape to refuse him. You just fell into his arms and let him comfort you for a while. It was like this morning when he had held you so tight. It was calm and safe and warm. You had became so relaxed that you didn’t notice when Steve laid back down to the couch, taking you with him. You settled on his chest, face in his neck and hands under his arm pits. And that was how you fell asleep with Steve Harrington for the second time in the same day.

#im posting early bc why not happy nye!#steve harrington#steve harrington x reader#steve harrington imagine#steve harrington headcannon#steve harrington reader insert#steve harrington fluff#steve harrington angst#steve harrington slow burn#stranger things imagine

696 notes

·

View notes

Text

[HM] The Ramblings of an Inept Alcoholic

I was always destined to be an alcoholic. My father drank, his brothers drank, and their father too: and when he lost the ability to swallow, he drank through an IV. He was a good drinker.

I was never sure if my mother was an alcoholic. She was the sort who just slumped in her chair and watched the telly. But she did that when she was sobre, if she ever was sobre, for all I knew she was perpetually inebriated: a far better position to be than in a perpetual state of level. I hesitate to contemplate such a thing. I do not think my father would have married her if such was the case. On second thought he most probably would have. From the lack of cohesion they share, it is reasonable to suppose that the wedding happened quite by accident, and that the whole exchange had been a mishap, that some other woman had been designated as my fathers wife, and that through a haze of drunk delirium, they had much to the misfortune of all, ended up together. To this day I believe that my father won her, or the woman she had replaced, in some drinking game.

My father is quite a drinker. Whether there is pride in my voice when I say this is up to further analysis. Pride is a thing that I have been taught to value only when it is there; and given that I lived my first, however many years, without it, I have quite forgotten its consistency. I recognize it in others, quite often: it is rather belittling. He always was a good drinker. Born to it. From the age of three he had learnt to swim, finding himself in vats of wine. First flask aged four, preferred it to my grandmothers tits: he says that it was less concentrated, less fiery down the gullet.

He was the sort of drinker, whose stories needed no exageration. This isn’t to say that there was no exaggeration, that were the case people’ld think him a lightweight. You have to be tall you see: every man, woman, child knows that your tales must be at minimum twice magnified: it shows discipline. See when he told of winning a town wide drinking contest, there was no lie told. So what does he do? He fabricates the elephant; his main contestant. A large one too. As he’d tell it: big as any building, and bigger still, greater than any tree of the forest, king of all elephants, it’s trunk larger than his wife: which was a trying task for any elephant: and involved a certain lack of proportion, but I garnered that my father’s knowledge of elephants stopped at its ability to drink.

My father was always supportive of me. I resented him for it. He would nod at me: a greeting that said “How do you do? Are you well?” He’d crack open a beer for me once or twice, perhaps by accident, but deeds over words as they say. And I hated him for it. His father beat him. His grandfather beat his father. And I was left, shame of the family, alone and unbeaten.

I suppose with the retrospect a clear mind can provide, that the blame lay on me. That I chose not to suck from my mother’s tit, that I chose not to earn my father’s belt. Born without nerves, into a world no longer tumultuous, into an era with nothing to protest. No oppressor, no pressure, no point to prove. I was given everything, and for that I received nothing.

Eight, the age at which I first tried drink. Brown, and smelling of disease. Pinched my nose and poured a small dosage down the back of my throat. I noticed two things, that it tasted as it smelled, and that I was about to die. I had taken far too large a dose, and there were no ice cubes to dilute it; and my throat was on fire, and I was going to asphyxiate. When I threw it up, my throat was burnt twice. Caught, red faced, so to speak, my father laughed. It was cheap. Neither his smile nor his eyes held disappointment, and I hated him for it. I didn’t touch the stuff again, until the age of twelve.

Smoking started, age ten. Even at that age I knew sobriety to be shameful. And I was teased at every interval by my uncles and their friends. The same ever repeating lines, a result of some alcohol induced brain damage, perhaps early onset dementia. I later strived to replicate such things. I never liked to smoke: it was an expense, it smelled bad, and I knew it to cause ulcerations of the stomach. But it hid the lack of alcohol on my breath, and that in itself was enough.

There were no kids my age, and by that I mean that there were two. One, a product of incest: so I was told, and so I believed; and had certain difficulties, but it may well have been foetal alcohol syndrome: and so I took a disliking to him. The other was female and fat, and that’s all I ever knew of her: Pregnant Penny her nickname. Our teacher, a television and the front cover of a graffitied textbook. Behind the desk and in a state of mellow high, a convicted sex offender. A fact, and the only words he ever spoke to us. I suppose that we were a disappointment. And in later years, when pubescent Penny made her attempt at seduction, she was returned to her seat with the raise of two eyebrows.

At twelve I discovered the older kids. And in return for cigarettes, I was allowed to remain, and to laugh at their jokes, which were implied to be humoristic. Their class was large, with five, and so I went unnoticed. Their teacher, a divorcee, slumped lifeless and dead. And through them I learnt much of the world. And I first tried beer, a bitter brown, resemblant of piss. It went down easy, but went up just as easy. There was neither disappointment nor disdain in their eyes. To support them, and to support myself, I found a job.

Too few people read for a paper route. The pub, a family business. The coffee shop, distasteful of my manners. And the church did not pay. It was in the rundown library that I found employment. The pay was poor, but the work paltry. A one person job, stretched to two, as to not stretch one's legs. The owner much resembled her cat, slumped at the checkout, her eyes beady, whiskers not so much as a twitch. The cat of course, was stuffed. I stacked, and stood, such that nothing was stolen. On occasion, my advice was sought, and with no experience of such things, the recognition of my opinion that is, I would simply recommend the most nuanced titles. Whether they were in search of classical literature, a light read, or a comic, a short walk to the pornographic section would ensure returning customers. From this too, I learnt much of the world. As with tobacco, you grow accustomed to the aroma. And when a man with round glasses, or a woman with a wrapped shawl, crossed our entrance, we would be shutting for lunch; and when they returned an hour later, we would be shutting for the day. On a Wednesday afternoon, a couple of years later, I would go in to find her dead at her desk. A coronary apparently. Two hours it took to notice, and only then from a build up in flatulence.

It was that same year in which my father caught me skipping class. At the park sharing a pack, brown paper bottle in hand, hearing of the excavation of a second cousin from Wisconsin in Canada. And out of a bush, a prickled bush, with thorns like knives, he emerged: distinguished in dishelvery. It took several seconds for his eyes to adjust, several more for surroundings, several more still to observe my presence, and several more that I was his son. Faint and faded smile, and he was gone. The last time that I hung with the older kids.

Sixteen and faced with a decision, uncertain of expectations, I buckled under the pressure and remained in education. Fueled by an alcoholic bulimia, I sought professional aid. And through the writings of Hemingway and S. Thompson, found a certain peace. Only for it to be blown away with the setting sun. Life polarized to the neon saturates and the drab muddy monochrome. Like any opiate, addiction was to happen in several well defined stages. And in recovery there were recurring thoughts of ending it: myself and the pain that came with unrequiting aspirations. All of this and more, quickly forgot in encountering Becky. A sightly slap to the face, overshadowed by its all too physical manifestation. She was the kind of abuse I had yearned for. Young love I supposed. All things come to an end, this too I supposed, witnessing her take a long and shafted suppository, in the school parking lot. Aged eighteen school ended, an unceremonious affair. On Monday it was there, and Tuesday it wasn’t. No one seemed to notice, no one cared. An ashen debris, with arson suspected. And I left for the city.

I became a writer, for they knew how to drink, to smoke, to revel in the ravellings of their own ineptitude. And I did just that, though drinking limited. Insomnia came and went, its passing a side effect of the caffeine and sedatives. I became a writer and did not write: my take on modern literature. My time occupying itself with music and movies, and I learnt that taste was subjective, pubs and clubs and bathroom stalls, with women most often whiskeyed. And then there came a time, when my card was declined, and there became need for a real occupation. And so, two weeks into the life of a writer, I found myself an accountant, with expectations, responsibilities, a thin black tie and a station of free coffee. The money was good, and I became a whore to the constitutional stability. It was only as I mused over the monthly and annual gym membership rates, that my subliminal sufferings became sentient.

The doctors offered sanctuary. A place to list my concerns: that I was twenty and recycling, that I listened to pop music, that this winter I was to ski in Aspen, and that I ate fair-trade, free-range, organic. And he listened, eyes sagged, and asked what I wanted. I responded ‘to drink, to be depressed, to have direction’. And I was given a prescription of sugar pills, and told to get married. A liver transplant, simply would not have been enough.

It was while in pursuit of a wife, that my mother passed. Mistook the highway for the couch. No funeral, no coffin, no cremation, a hole in a field. And sat atop her, I wandered whether pissing or weeping was more appropriate. I supposed it unprecedented. And in any case, my bladder was barren, and there were no onions at hand.

My uncles at forty, were put in a home. Their minds bent and broken, unable to recall which twin they were, unable to finish their own sentences. All culminating in an altercation, in which one brother mistook the other for a mirror, eliciting two broken noses, and enough blood for several large scale transfusions.

We had neither the money nor the sentiment to pay. Instead, an exchange of prisoners. We took two men, ages unknown, providing them a bench in a park, a wholemeal loaf and the company of half fledged pigeons: the neighbouring ducks being an indecent bunch. A homeless shelter stood not half a mile away. A better life.

My uncles were left dry but miniatures: a sip a day. In a purgatory, self-made and self-deserved. Anticipating response, our contact numbers were left in sharpie, stamped upon their wrists. In hindsight, a tattoo might have lasted longer. This was the last we saw of our uncles.

My father's time would come decades later. He clung to life as a tick, yet to drink his fill. I would visit sporadically, mainly for demotivation; a reminder of wasted potential. At a certain point, he was moved, with great force, out of his residency. Henceforth his habitation of the local bar, became in perpetuity. Had a squatter maintained his rights, the pub would be under new management. But a squatter had no rights, my father neither, and he found himself a gravitational force for tourists, who would gawp in reticent inertia. During one such display of excessive drinking, he self-ignited, gaining for himself a sizeable applause. I thought it in poor taste, combustion being the leading cause of climate change and all.

His death hit national news, with a civil lawsuit being filed against the liquor distributor. International news came next, and through which I garnered an appearance on a talk show. The whole run-up being rather insidious, as I prepared to defile my father’s name. A publicist prepped me on dress and on what could be said: which was very little, and was most ninety percent made up by a would-be screenplay writer, assistant of hers. A publicist working for a group of lawyers, whose representation I never solicited, in a trial I never sought, to which end I struggled to discern; but the amenities were above par, and for that I went along supposing it a potential anecdote.

His name... I misremember, but was American and smooth, like coffee. His temperament too: coffee or cocaine, perhaps the two. And his laugh almost natural, and his hair shone as a Sub-Saharan sun, and was moulded in such a way that I was reminded of Marie Antoinette. My spiel was made less dry, by a tangential discussion on the legalisation of cannabis. My view being, it was detrimental to the youths of tomorrow: fewer laws to violate. They thought it British sarcasm, I thought them sheep to the hypocrisy of liberalisation.

I went from being an accountant to having an accountant, and an attempt at being sophisticated and civil. With wines red, not rough, conversations loaded in undertone, and orchestras and operas and an all female rendition of Othello. But sociability did not stick, it bore far too much resemblance to emphatic boredom. So I left it all behind.

And that was my life, at least that which was worth reading about, and which was not too explicit. That most moments were in relation to another, is either the defining characteristic of the human condition, or evidence of my position as a bystander to my own undefined life.

___________End___________

Authors comments/ what I think of it: 1) The beginning sucks, the first few paragraphs need work. 2) The structure is a little simplistic and could be improved. 3) There are a couple of sentences that feel out of place i.e. they are too poetic 4) There are some sentences that dont flow well together. I.e. it feels abrupt 5) The end is as abrupt as an end can be, and it seems to confuse people. 'that most moments were in relation to another': another means 'another person' instead of 'another moment'. Don't know how obvious that is. But adding person would ruin the flow of the sentence.

Wouldn't mind other opinions? This is the first thing I've written that I thought was (despite shortcomings). Is it actually good?

submitted by /u/blueycarter [link] [comments] via Blogger https://ift.tt/35WLSPj

0 notes