#what does criminogenic mean

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

RnR Leads Manager: A Game-Changer for Businesses

RnR Leads Manager: In today’s fast-paced and competitive business landscape, staying ahead means effectively managing leads and converting them into customers. The RnR Leads Manager has proven to be a game-changer for businesses of all sizes, offering a dynamic solution for managing customer interactions and ensuring no potential lead slips through the cracks. In this comprehensive guide, we explore why this tool is a must-have for businesses aiming to scale, streamline their processes, and increase their revenue.

#managed it#criminogenic needs#manageit#gage r&r#lead generation#it service management (industry)#lean#advan#human resource management#react native#iso 9001 2015 quality management systems#advertising#what does criminogenic mean#lean six sigma#measurement system analysis#case mangement#measurement systems analysis#employee engagement#bangladesh (country)#potomacperformance#iso 9001 2015 qms certification assistant#gaming market analysis

0 notes

Text

Pluralist, your daily link-dose: 22 Feb 2020

Today’s links

Tax Justice Network publishes a new global Financial Secrecy Index: US and UK, neck-and-neck

What Marc Davis lifted from the Addams Family while designing the Haunted Mansion: Amateurs plagiarize, artists steal

ICANN should demand to see the secret financial docs in the .ORG selloff: at least it’s an Ethos

Wells Fargo will pay $3b for 2 million acts of fraud: they shoulda got the corporate death penalty

This day in history: 2019, 2015, 2010

Colophon: Recent publications, current writing projects, upcoming appearances, current reading

Tax Justice Network publishes a new global Financial Secrecy Index (permalink)

The Tax Justice Network just published its latest Financial Secrecy Index, the leading empirical index of global financial secrecy policies. The US continues to make a dismal showing, as does the UK (factoring in overseas territories).

https://fsi.taxjustice.net/en/

Both Holland and Switzerland backslid this year.

Important to remember that “bad governance” scandals in poor countries (like the multibillion-dollar Angolaleaks scandal) involve rich financial secrecy havens as laundries for looted national treasure.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/19/isabel-dos-santos-revealed-africa-richest-woman-2bn-empire-luanda-leaks-angola

As Tax Justice breaks it down: “The secrecy world creates a criminogenic hothouse for multiple evils including fraud, tax cheating, escape from financial regulations, embezzlement, insider dealing, bribery, money laundering, and plenty more. It provides multiple ways for insiders to extract wealth at the expense of societies, creating political impunity and undermining the healthy ‘no taxation without representation’ bargain that has underpinned the growth of accountable modern nation states. Many poorer countries, deprived of tax and haemorrhaging capital into secrecy jurisdictions, rely on foreign aid handouts.”

Talk about getting you coming and going! First we make bank helping your corrupt leaders rob you blind, then we loan you money so you can keep the lights on and get fat on the interest (and force you to sell off your looted, ailing state industries as “economic reforms”).

The Taxcast, which is the Network’s podcast, has a great special edition in which the index’s key researchers explain their work. It’s always a good day when a new Taxcast drops.

https://www.taxjustice.net/2020/02/20/financial-secrecy-index-who-are-the-worlds-worst-offenders-the-tax-justice-network-podcast-special-february-2020/

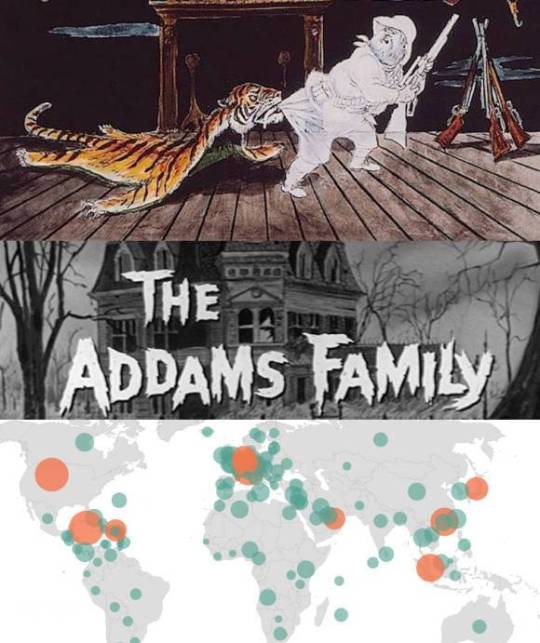

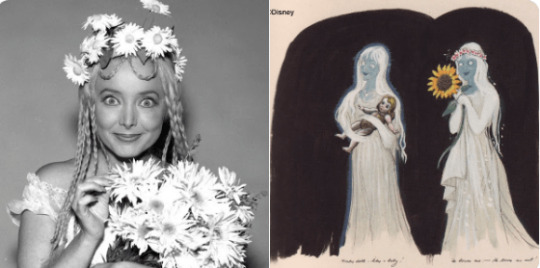

What Marc Davis lifted from the Addams Family while designing the Haunted Mansion (permalink)

It’s always a good day — a GREAT day — when the Long Forgotten Haunted Mansion blog does a new post, but today’s post, on the influence of the Addams Family TV show on Mansion co-designer Mark Davis? ::Chef’s Kiss::

https://longforgottenhauntedmansion.blogspot.com/2020/02/the-addams-family-and-marc-davis.html

It’s clear that Davis was using Addams’s comics as reference, but, as Long Forgotten shows, the Davis sketches and concepts are straight up lifted from the TV show: “Amateurs plagiarize, artists steal.”

Some of these lifts are indisputable.

“Finally, it’s possible that Davis took a further cue from the insanely long sweater Morticia is knitting in ‘Fester’s Punctured Romance’ (Oct 2, 1964), but in this case I wouldn’t insist upon it.”

Likewise, from the TV show, “Bruno” the white bear rug that periodically bites people was obviously the inspiration for this Davis sketch for the Mansion. Long Forgotten is less certain about “Ophelia,” but I think it’s pretty clear where Davis was getting his ideas from here.

Davis was an unabashed plunderer and we are all better for it! “We’ve seen many other examples of Marc Davis taking ideas from here, there, and anywhere he could find them, but not many other examples of multiple inspiration from a single source.”

ICANN should demand to see the secret financial docs in the .ORG selloff (permalink)

ISOC — the nonprofit set up to oversee the .ORG registry — decided to sell off this asset (which they were given for free, along with $5M to cover setup expenses) to a mysterious private equity fund called Ethos Capital.

Some of Ethos’s backers are known (Republican billionaire families like the Romneys and the Perots) but much of its financing remains in the shadows. We do know that ICANN employees who help tee up the sale now work for Ethos, in a corrupt bit of self-dealing.

The deal was quietly announced and looked like a lock, but then public interest groups rose up to demand an explanation. Not only could Ethos expose nonprofits to unlimited rate-hikes (thanks to ICANN’s changes to its rules), they could do much, much worse.

If a .ORG registrant dropped its domain, Ethos could sell access to misdirected emails and domain lookups – so if you watchdog private equity funds and get destroyed by vexation litigation, Ethos could sell your bouncing email to the billionaires who crushed you.

More simply, Ethos could sell the kind of censorship-as-a-service it currently sells through its other registry, Donuts, which charges “processing fees” to corrupt governments and bullying corporations who want to censor the web by claiming libel or copyright infringement.

Ethos offered ISOC $1.135b for the sale, but $360m of that will come from a loan that .ORG will have to pay back, a millstone around its neck, dragging it down. Debt-loading healthy business as a means of bleeding them dry is a tried-and-true PE tactic – it’s what did in Toys R Us, Sears, and many other firms. The PE barons get a fortune, everyone else gets screwed.

The interest on .ORG’s loan will suck up $24m/year — TWO THIRDS of the free money that .ORG generates. .ORG is a crazily profitable nonprofit – it charges dollars to provide a service that costs fractional pennies, after all. In response to getting slapped around by some Members of Congress, the Pennsylvania AG, and millions of netizens, Ethos has made a promise to limit prices increases…for a while. And they say that they’ll be kept honest by the nonbinding recommendations of an “advisory council” whose members Ethos will appoint and who will serve at Ethos’s pleasure.

In a letter to ICANN, EFF and Americans for Financial Reform have called for transparency on the financing behind the sale: “hidden costs, loan servicing fees, and inducements to insiders.”

https://www.eff.org/press/releases/eff-seeks-disclosure-secret-financing-details-behind-11-billion-org-sale-asks-ftc

Wells Fargo will pay $3b for 2 million acts of fraud (permalink)

Wells Fargo stole from at least two million of its customers, pressuring its low-level employees to open fake accounts in their names, firing employees who refused (refuseniks were also added to industry-wide blacklists created to track crooked bankers). These fake accounts ran up fees for bank customers, including penalties, etc. In some cases, the damage to the victims’ credit ratings was so severe that they were turned down for jobs, unable to get house loans or leases, etc.

The execs who oversaw these frauds had plenty of red flags, including their own board members asking why the fuck their spouses had been sent mysterious Wells Fargo credit cards they’d never signed up for. Though these execs paid fines, they got to keep MILLIONS from this fraud (which was only one of dozens of grifts Wells Fargo engaged in this century, including stealing from small businesses, homeowners, military personnel, car borrowers, etc). Some of them may never work in banking again, but they’re all millionaires for life.

Now, Wells Fargo has settled with the DoJ for $3b, admitting wrongdoing and submitting to several years of oversight. That’s a good start, but it’s a bad finish.

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-51594117

The largest bank in America was, for DECADES, a criminal enterprise, preying on Americans of every description. It should no longer exist. It should be broken into constituent pieces, under new management. There would be enormous collateral damage from this (just as the family of a murderer suffers when he is made to face the consequences of his crimes). But what about the collateral damage to everyone who is savaged by a similarly criminal bank in the future, emboldened by Wells Fargo’s impunity?

Wells Fargo is paying a fine, but will have NO criminal charges filed against it.

https://newsroom.wf.com/press-release/corporate-and-financial/wells-fargo-reaches-settlements-resolve-outstanding-doj-and

If you or I stole from TWO MILLION people, we would not be permitted to pay a fine and walk away.

“I’ll believe corporations are people when the government gives one the death penalty.”

This day in history (permalink)

#15yrsago: Kottke goes full-time https://kottke.org/05/02/kottke-micropatron

#15yrsago: New Zealand’s regulator publishes occupational safety guide for sex workers: https://web.archive.org/web/20050909001954/http://www.osh.dol.govt.nz/order/catalogue/pdf/sexindustry.pdf

#10yrsago: Principal who spied on child through webcam mistook a Mike n Ike candy for drugs: https://reason.com/2010/02/20/lower-pervian-school-district/

#10yrsago: School where principal spied on students through their webcams had mandatory laptop policies, treated jailbreaking as an expellable offense https://web.archive.org/web/20100726204521/https://strydehax.blogspot.com/2010/02/spy-at-harrington-high.html

#10yrsago: Parents file lawsuit against principal who spied on students through webcams: https://abcnews.go.com/GMA/Parenting/pennsylvania-school-webcam-students-spying/story?id=9905488

#1yrago: Cybermercenary firm with ties to the UAE want the capability to break Firefox encryption https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/02/cyber-mercenary-groups-shouldnt-be-trusted-your-browser-or-anywhere-else

#1yrago: Fraudulent anti-Net Neutrality comments to the FCC traced back to elite DC lobbying firm https://gizmodo.com/how-an-investigation-of-fake-fcc-comments-snared-a-prom-1832788658

Colophon (permalink)

Today’s top sources: Naked Capitalism (https://nakedcapitalism.com/).

Hugo nominators! My story “Unauthorized Bread” is eligible in the Novella category and you can read it free on Ars Technica: https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2020/01/unauthorized-bread-a-near-future-tale-of-refugees-and-sinister-iot-appliances/

Upcoming appearances:

The Future of the Future: The Ethics and Implications of AI, UC Irvine, Feb 22: https://www.humanities.uci.edu/SOH/calendar/event_details.php?eid=8263

Canada Reads Kelowna: March 5, 6PM, Kelowna Library, 1380 Ellis Street, with CBC’s Sarah Penton https://www.eventbrite.ca/e/cbc-radio-presents-in-conversation-with-cory-doctorow-tickets-96154415445

Currently writing: I just finished a short story, “The Canadian Miracle,” for MIT Tech Review. It’s a story set in the world of my next novel, “The Lost Cause,” a post-GND novel about truth and reconciliation. I’m getting geared up to start work on the novel now, though the timing is going to depend on another pending commission (I’ve been solicited by an NGO) to write a short story set in the world’s prehistory.

Currently reading: I finished Andrea Bernstein’s “American Oligarchs” this week; it’s a magnificent history of the Kushner and Trump families, showing how they cheated, stole and lied their way into power. I’m getting really into Anna Weiner’s memoir about tech, “Uncanny Valley.” I just loaded Matt Stoller’s “Goliath” onto my underwater MP3 player and I’m listening to it as I swim laps.

Latest podcast: Persuasion, Adaptation, and the Arms Race for Your Attention: https://craphound.com/podcast/2020/02/10/persuasion-adaptation-and-the-arms-race-for-your-attention/

Upcoming books: “Poesy the Monster Slayer” (Jul 2020), a picture book about monsters, bedtime, gender, and kicking ass. Pre-order here: https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781626723627?utm_source=socialmedia&utm_medium=socialpost&utm_term=na-poesycorypreorder&utm_content=na-preorder-buynow&utm_campaign=9781626723627

(we’re having a launch for it in Burbank on July 11 at Dark Delicacies and you can get me AND Poesy to sign it and Dark Del will ship it to the monster kids in your life in time for the release date).

“Attack Surface”: The third Little Brother book, Oct 20, 2020.

“Little Brother/Homeland”: A reissue omnibus edition with a very special, s00per s33kr1t intro.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The type of criminologist I think I’m becoming (Reflective practice)

When i reflect back on the theories i have learned in criminology, I think I am becoming a left-wing criminologist who believes in the right wing crime reduction tactics. I believe Capitalism as an economic system is criminogenic as Marxist Criminologist Gordon argued because I think it is clear that the nature of capitalism does promote crime because we are all exposed to the same material wants and desires and the truth is some people cannot afford material possessions but still want them so might try and get them illegally. And I do agree with Left realists that Poverty and marginalisation does lead people into criminal activity, especially younger people, poorer people and ethnic minorities who are more likely to be poor. Therefore, the government (I now know you call them The State) Should do more to offer marginalised groups greater opportunities to earn money legitimately through education and training opportunities. Which means I do believe governments have a duty to address the social and structural problems that lead people into criminality. However, I also believe that being tough on crime, as Right Realists suggests is important in society because it makes people feel safe and gives people a sense of justice when someone is punished for committing crime. Zero tolerance does work because it has been shown to reduce crime significantly. I also believe in visible policing. Seeing the police in communities will make people feel safe. I have also learned that generally in British society there is not much respect for the police. So visible policing in communities and crime reduction would make people feel more confident in the ability of the police to keep them safe. It’s clear that as a criminologist I believe the government (the State) should use resources to remove the social causes of crime but at the same time put resources into reducing crime, even if it requires a tougher approach to policing communities. I would never have thought this deeply about crime without having to reflect upon what the theories argue and how i feel about their arguments.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rejecting and Ejecting the Poor: The Victimization and Criminalization of Poor Black People in the Most "Radical" City on the Planet

Project Eject is More Than What Meets the Ear

On a cold, gray and dreary day in Jackson, Mike Hurst, the man appointed U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Mississippi by the Trump administration, stood in front of the United States courthouse flanked by various law enforcement agencies, politicians and community "leaders" to announce a new crime prevention initiative called Project Eject.

In his remarks to the media, Hurst claimed to "...want to empower Jackson and its citizens, expel crime from our communities, and work together to make our Capital City safe for everyone." We should all be aware that the implications of Project Eject are much deeper and more sinister and can and should be counted as part of a long line of legalized victimization of poor Black people in Mississippi.

A Critical Analysis of Project Eject and The Impact It will Have on Poor Black People

Project Eject is a racially bigoted and elitist program that gives expression to Donald Trump's and U.S. Attorney General Jefferson Sessions' national tough on crime agenda. It is harsh, punitive and extremely short sighted. It is designed to criminalize poor Black people and other social forces in Jackson that the Trump administration has deemed a threat to its hegemony. Project Eject will begin the process of ethnically cleansing Jackson of poor Black people so that capital and capitalists can operate more comfortably in Mississippi’s Capital City.

If capital is allowed to further entrench itself in Jackson, poor and working class Black people will be herded out of Jackson through a number of economic and political maneuvers that have been employed in cities like Detroit, MI, Washington, D.C. and Oakland, CA to name a few. Hurst promised that those prosecuted under Project Eject will be sent out of state to serve federal sentences without parole. Should more capital-friendly policies like this one go unchallenged, the likelihood of people incarcerated under Project Eject being able to come home to Jackson will drop precipitously, as the communities they left will have been destroyed; priced out and pushed out to make room for those deemed more desirable by capital and capitalists. .

The Lumumba administration has already set the stage for the implementation of this brand of policies by declaring Jackson “open for business” and “business friendly”. . Mayor Lumumba's has stated repeatedly n that he wants people (read: corporations because the law views corporations as people) to come to Jackson to make a lot of money and become rich. These overtures to capital and capitalist development will make the ethnic cleansing of poor Black people from Jackson inevitable. Despite the Mayor’s stipulation that these corporations must invest back into the people of Jackson to do business here, capital cannot and will not respect this request. That is simply not how capitalism works. Capitalist corporations exploit people. They do not invest in them. It must be understood that whatever "investment" that might be interpreted as going into residents is really an investment into their bottom line.

Project Eject will sever those convicted from the support systems that are proven to increase the likelihood of successful rehabilitation and reentry. Furthermore, the forced relocation of those incarcerated will place a tremendous economic, psychological and emotional burden on poor and working class black families, many of whom will undoubtedly want to make attempts to visit and support their loved ones who are being housed in prisons that are hundreds of miles away from Mississippi.

The supporters of Project Eject are sending a message of disdain for poor and working class Black people in the city of Jackson while disguising it with a disingenuous desire to help the city of Jackson with what they view as the problem of crime and violence. They are, in effect, saying that poor Black people in Jackson are irredeemable and should be discarded from the city like yesterday's trash. This line of thinking negates the humanity of people charged and convicted of crimes and looks to brand them as sub-human and worthy of inhumane treatment.

An Emphasis on Effects While Ignoring Causes

The narrative around Project Eject is that crime and violence in Jackson is out of control and that criminals must be brought to heel by whatever legal or extralegal means possible. Tough on crime proponents love to point out effects, but if we are serious about ending crime and violence in the city of Jackson and in Mississippi, we must also investigate the causes of the anti-social behaviors that we see and the systems and individuals that are at the root of them.

State Violence and Criminality Begets Community Violence and Criminality

Poor Black people who engage in antisocial and criminal behavior are the victims of unjust and evil social, political and economic orders. Every time we see a homeless person, families living in abject poverty, human beings being caged like animals, or a mentally ill person walking down Capitol Street eating out of trash cans, we should be reminded of the type of violence that is being heaped upon poor people and Black people everyday in this city. We should be mindful of how this descending violence coming down on the people from the highest echelons of this society fuels the lateral violence we see in our communities.

The government on the federal, state or local level do not want to deal with this reality. Because to talk about the reality of how the violence that is perpetuated against poor and Black people begets the violence that we see in our communities would call into question the way the economic, political and social systems are failing people. More people would be forced to interrogate and ultimately see the high levels of exploitation seen in this capitalist economic system as incompatible with a just and humane society.

Deny, Cover Up, and Eject

It is easy to condemn individuals and throw them away by labeling them as deviant, violent aberrations. It is easy for the State to deny the central role it plays and has always played in fomenting and maintaining a certain homeostasis of crime, violence and dysfunction. Upholding this false narrative ensures that poor and working class Black people can not sustain long term resistance to our oppression. If we allow those in power to do this, we lend legitimacy to this story and we allow the State to cover up the vast amount crimes it has and continues to perpetuate against poor and working class Black people. To allow law enforcement to eject poor Black people from Jackson is allowing them to bury the evidence of this state's civil and human rights abuses against Black people.

The Current System Produces Violence and Criminality

The truth of the matter is that this society produces, then profits from violence and criminality. As evidence, the United States has over 2 million people, more than any other country in the world, who are currently locked in cages. Most of these people are locked away for crimes of violence. We have to come to grips with the reality that violence and criminality is what this society produces because this is what this country was founded upon.

The perpetuation of violence and crime does not develop in a social vacuum and contrary to what many may want to believe, there is no such thing as a criminal or violence gene that predisposes certain people to being more violent and criminal than others. Criminality and violence develops within a larger context.

The larger social and cultural context of America is violent. American culture celebrates dominance, violence, and the total annihilation of adversaries in popular culture, sports and the propaganda of the U.S. Military industrial complex.

Black people have been subjected to untold amounts of physical violence, surveillance and economic reprisals because we have always been viewed as a threat to the established hegemonic order of the United States. Violence is how this country maintains its stature and power in the world. Violence is how it exacts control over its subjects. This country is criminogenic and cannot and would not exist without violence. Therefore, it is hypocritical for the State to act surprised that the people who they have violently oppressed in perpetuity would commit acts of violence among themselves and others.

Instead of talking about how the various forms of violence perpetrated against poor and Black people in this country and specifically in Mississippi begets the violence we see on an interpersonal level in our communities, we have federal, county and city officials who want to lay the blame at the feet of people who have suffered under the extreme oppression and violence of the social, economic and political order they have been forced to exist under.

Black people have been rendered disposable by a perpetually inadequately funded and failed education system, an economy that has no use for us outside of slave labor in public and private prisons, and systematic and unrelenting racial oppression. It is not surprising that many poor Black people engage in violence and other antisocial behaviors. In fact, it is surprising that in light of the trauma that Black people have been subjected to, that more Black people don't engage in these types of behavior.

Project Eject Continues Ethnic Cleansing in Mississippi

From the nineteen teens until the early 1970s millions of Black people left the south for northern urban cities. The dominant historical narrative is that Black people left their homes, familiarity and families to find greater economic opportunities in the factories and steel and textiles mills of the north. To some degree this is true, but not all Black people left the only homes they had ever known of their own volition. In many instances, Black people were forcibly removed from southern cities and towns in Mississippi. Project Eject plans to continue this type of forcible removal.

Historically, Black people have also been run out of Mississippi through outright violence, terroristic threats, land theft and economic exploitation. This was not voluntary migration. This was forced migration and ethnic cleansing carried out in the southern United States.

One of the reasons that some Black people were run out of places like Mississippi is because white people created a narrative that they were lazy, criminal vagrants who did not want to work. The reality was that poor Black people who had seen their parents and great grandparents economically exploited and subjected to slavery by another name did not want to continue to allow their labor to be exploited by the racist white families that had previously owned their fore parents. That is why it was quite disturbing to hear U.S. Attorney Hurst refer to some people as nothing more than criminals that he does not want to be in the city. Criminal is a code word for poor Black people who do not fit into the plans that the ruling class has for the Capital city.Since Black people can no longer be outright killed or run out of town without some outcry, Project Eject is a legal way of ethnically cleansing this undesirable class of people from the population of Jackson to make way for people who they deem more valuable to the future of Jackson.

Both individuals like Hurst and many from the Black political class in Jackson are unwilling to attempt to solve the problems that produce poverty, crime and violence so shipping them off is an easy fix. By the time they spend a decade or more in prison, they will not be able to come back to Jackson because the likelihood that there families will be priced out of their homes and moved to the outside of Jackson are great.

Black Collaborators

The saddest, but not surprising part of the Project Eject press conference was the sea of Black faces surrounding Hurst as he made the announcement that he planned to eject Black people from the city. As a human defense lawyer, I see the people who Hurst's message was directed toward on a daily basis. Most of them are young Black men who have been either miseducated or not educated at all. These young men could be the children or grandchildren of the Black elected officials and community "leaders" who stood with Hurst as he laid out his plan to Eject them from the city.

The sad reality is that in addition to being failed by the dominant society, the Black political class and the Black community at large has failed them too. As it stands, there are no viable options or opportunities for poor Black youth in the city of Jackson. On the one hand, this vacuum exists because we have not invested enough in our own children in terms of building the necessary independent economic, political or social institutions necessary to speak to the unique needs of Black children and young adults and prepare them for a racist and hostile society. On the other hand, this vacuum exists because Black elected officials year after year have merely talked about what Black youth need instead of using to the city's resources to meet those needs.

Real Solutions

For the misguided, Project Eject represents the opportunity for a respite from crime and violence. However, the problem of crime and violence cannot be solved through over policing and tough on crime policies.

Crime in Jackson must be treated as a public health crisis. People must be provided mental health services, substance abuse treatment and economic democracy through control of the means of production. Ultimately, if we are serious about bringing crime and violence to a minimum in Jackson, we must prepare ourselves to dismantle the current political, economic and social order. It is this order that keeps poor people generally and poor Black people specifically going through a cycle of crime and violence as both perpetrators and victims. This cyclical process benefits the ruling elite's agenda to have poor Black people trapped inside of the prison industrial complex and locked outside of the city.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seeking fresh perspectives on reentry and recidivism challenges

Brent Orrell, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, has this notable new Hill commentary under the headline "Rethinking pathways to reentry." I recommend the piece in full, and here are excerpts:

[A] declining prison population necessarily means that thousands of individuals are taking the arduous road back from prison to their communities. For many, this road ends up looking more like a roundabout than a highway, with more than 80 percent being arrested again less than a decade after release. Much has been tried to reduce recidivism but little has been shown to have significant positive effects. Over the past year, the American Enterprise Institute convened a group of scholars to delve into this problem, bringing together more than two dozen program evaluators, criminologists, and researchers to discuss what works and what does not in helping formerly incarcerated individuals successfully leave prison and reintegrate back into their communities.

Our research report sought to distill some insights into the state of research and practice in reentry with the goal of identifying fresh perspectives for policymakers, researchers, and practitioners working in the field. Many of these ideas will be more fully developed as part of a volume to be published in early 2020. While the working group did not seek to develop a consensus, it did identify several critical areas of focus for advancing the work of the corrections and reentry fields.

First, it is crucial that programs operating within correctional systems and at the community level become more rigorous in their program designs. Correctional systems and reentry programs at the community level need clearly defined theories of change that lay out a strategic conceptual framework, detailed steps for reaching the desired outcomes, and metrics for determining success. In criminal justice and reentry, causality is hard to establish and measure, and such theories would help.

Second, researchers need to focus more time and energy on program implementation. Many correctional institutions and local criminal justice systems are either unequipped or uninformed or both about how to put a particular program model into practice. The result is a mashup of partially implemented programs that bear little resemblance to the models they are based on....

The report also highlights the importance of accurately gauging the needs of incarcerated individuals and their criminogenic risk factors. The best research shows that tailored services produce better outcomes than “one size fits all” programs that run the risk of providing individuals either too little or too much help. To effectively align services with individual needs, correctional staff must understand criminogenic risk factors and align services to mitigate them. These assessments might be expensive and time consuming, but the benefits outweigh the costs.

Finally, new research indicates that people may stop committing crimes suddenly rather than desist on a slow age related curve, a model that has governed our criminal justice expectations for decades. There is evidence that even those who seem most likely to recidivate make choices to become crime free, quickly reducing or eliminating the likelihood of rearrest. While there is uncertainty about how to produce this shift, the research suggests that reentry programs should be oriented to support those who have made or are close to making the transition.

All levels of government, along with many private and philanthropic organizations, have invested billions of dollars in trying to solve the recidivism puzzle. To date, the effect has been disappointing. This report and the volume that will be published next year are an effort to plot multiple pathways toward possible solutions. Some of these pathways focus on making existing approaches more effective while others seek to innovate entirely new solutions. The bottom line is that the status quo is neither sufficient nor sustainable. For the sake of the thousands of men and women who return home from prison each week and the families and communities who receive them, we can and must do better.

The full American Enterprise Institute report discussed in this commentary is available at this link under the title "Rethinking reentry: An AEI working group summary."

from RSSMix.com Mix ID 8247011 https://sentencing.typepad.com/sentencing_law_and_policy/2019/10/seeking-fresh-perspectives-on-reentry-and-recidivism-challenges.html via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Link

Hope Reese | Longreads | May 2019 | 16 minutes (4,345 words)

In our current criminal justice system, there is one person who has the power to determine someone’s fate: the American prosecutor. While other players are important — police officers, judges, jury — the most essential link in the system is the prosecutor, who is critical in determining charges, setting bail, and negotiating plea bargains. And whose influence often falls under the radar.

Journalist Emily Bazelon’s new book, Charged, The New Movement to Transform American Prosecution and End Mass Incarceration, brings to light some of the invisible consequences of our current judicial system — one in which in which prosecutors have “breathtaking power” that she argues is out of balance.

In Charged, a deeply-reported work of narrative nonfiction, Bazelon tells the parallel stories of Kevin, charged with possession of a weapon in Brooklyn, New York, and Noura, who was charged with killing her mother in Memphis, Tennessee, to illustrate the immense authority that prosecutors currently hold, how deeply consequential their decisions are for defendants, and how different approaches to prosecution yield different outcomes. Between these stories, she weaves in the recent push for prosecutorial reform, which gained momentum in the 2018 local midterm elections, and the movement away from mass incarceration.

I spoke to Bazelon — currently a staff writer for The New York Times Magazine and cohost of the Slate Political Gabfest — on the phone, discussing problems with mandatory sentencing and what the public should know in order to make informed decisions when voting for their local D.A., among other subjects. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

*

Hope Reese: In the 80s and 90s, prosecutors began to hold much greater power in the judicial system than they previously had. You write that in the 30 years between then and now, Americans “first embraced punishment levels lower than Sweden’s, then built a justice system more punitive than Russia’s.” How did such a drastic increase in power occur?

Emily Bazelon: In the late ’70s, crime starts to go up. Even before that you have a turn by politicians — starting with Barry Goldwater, then Richard Nixon, and then later Ronald Reagan — toward a very law-and-order fear-mongering platform, arguing that people who commit crimes need to be locked up for a long time. It’s pretty racialized rhetoric. The combination of fear actually rising and then the politicians capitalizing on it leads to much stricter sentencing laws. Part of this is just increasing the penalties, but part of it is mandatory minimum sentences.

The idea of this mandatory minimum sentence is that you’re going to take discretion out of the system by tying the hands of judges, right? Like if they have to give a certain sentence, then you won’t have to worry about a “softie” judge. The problem is, you can’t really take discretion out of the criminal justice system. It has to continue to live somewhere, and mandatory minimum sentences, even though no one really described it this way while it was happening, give discretion to prosecutors — because suddenly the charge determines the punishment.

And so the charging shifts power to prosecutors, and in addition plea bargaining, in a couple of ways. One way is that once you have mandatory sentences, it’s easier for prosecutors to force plea bargains, because they have so much more leverage. And another thing that happened basically simultaneously is that the criminal codes expand, so there are just more things to get charged with, and more choices of charges, so prosecutors can stack charges. And that also increases the penalty and increases leverage and basically makes the trial disappear in American law. You end up with what we have now, which is like a 2 percent trial rate in a lot of state court systems.

Do mandatory sentences lead to crime reduction?

Yeah, a little bit. I mean, there’s a lot of debate over what leads violent crime to fall in the United States, really more in the late ’90s through the 2000s. The comprehensive big literature review by the National Academy of Sciences finds that increased sentences have what they call a best to modest effect on reducing crime. So in other words, you take people off the streets. You lock those people up. Those particular people are not going to be committing crimes outside of prison, and there’ll be some other people who are deterred, but I think the question that criminologists and really lots of people increasingly ask is: Is that modest impact worth the human cost?

Especially because there’s new studies showing that jail and prison are what’s called criminogenic. That’s like carcinogenic. Like, they actually cause crime in the medium to longer term. The idea is yeah, you lock people up in the shorter term, but almost everyone gets out — and when they get out, they tend to be more desperate, have a harder time getting a job, finding housing, and those things all correlate with being more likely to commit crimes afterward. I think at this point, most of these people would agree that American sentences are way out of proportion to what we need for deterrence, and in fact, are having a negative effect.

I could only find two instances in which two different prosecutors went to jail for a few days each, like in the whole history of prosecutorial misconduct.

You write about how prosecutor culture, which values confidence and speed over caution and delay, can be a problem for giving people fair chance under the law. How we could start to change that?

Yeah. So this has to do with the culture of prosecutors’ offices, how we train prosecutors, and what we tell them we value. On paper they have a dual responsibility. They’re supposed to win convictions and also be ministers of justice, but in practice a lot of prosecutors’ offices reward prosecutors for winning big trials and getting long sentences. As long as you have that kind of reward system in place, you’re valuing stricter punishment over second chances.

To change that you have to start recognizing people who are declining to charge someone, or for dropping the charges if the case is weak. Or for putting more people into alternatives to our incarceration program. It’s really changed how we define the job and how we define success of the job.

You describe the first steps of being charged, and how it’s often tricky with circumstantial evidence, illegal evidence-gathering, or police who aren’t issuing Miranda rights. You call this part of the “rotten foundation” that cases are often built on. How is this happening?

Well I think that there are a few things going on. One is just the problem of how much evidence prosecutors actually have to put forward. If you never have a trial, then your case isn’t going to be truly tested, and so you’re going to be able to assert a lot of things that may or may not be true without really being accountable for those facts. This is something that, to some degree, varies state-by-state, because some states have enacted better laws for sharing evidence early in a case with the defense, long before a trial. But it’s still an ongoing issue, and I think what you’re really seeing here is how the decline of the trial intersects with the lack of accountability for prosecutors.

Then I think the other kind of related issue I was writing about with Noura’s case is this problem of what people call tunnel vision or confirmation bias. Once the police have arrested someone, there’s an incentive to think that that’s the person who did it. It’s sort of normal human psychology to emphasize facts that confirm your pre-existing beliefs as opposed to challenging them.

Local Bookstores Amazon

How much is decided at the whim or discretion of prosecutors when it comes to determining the charge for a crime?

Well, I mean, prosecutors work closely with the police, so it’s not like they’re doing this themselves. But prosecutors are the people who bring charges. That’s their job.

So they bring charges — but they are also guaranteed immunity from repercussions, which is not the case with police. How did that happen, and what does absolute immunity actually mean in practice?

Absolute immunity comes from a Supreme Court decision called Imbler vs. Pachtman. Absolute immunity is unusual for government officials. The cops, for example, have qualified immunity. Absolute immunity means that if you can argue something you did, however bad, was in the course of doing your job, you cannot personally be sued for it. It’s like a very blanket protection, and so it has meant that it’s virtually impossible to sue prosecutors personally.

And then there’s sort of some problems compounding that rule. The Supreme Court in a later case called Connick vs. Thompson made it very difficult to sue a district attorney’s office, so then you have the whole office being shielded, absent a pattern or practice of misconduct, and then they made it really hard to prove the pattern of misconduct. And when the Supreme Court decided Imbler, they kind of reassuringly said, “Oh, don’t worry. A prosecutor who commits misconduct will be prosecuted him or herself.” But that doesn’t really happen. I mean, I could only find two instances in which two different prosecutors went to jail for a few days each, like in the whole history of prosecutorial misconduct.

And then the last piece of this is that the Supreme Court also said, “Oh don’t worry, because the bar, the legal profession, will discipline prosecutors.” But that is also very unusual, and I tell the story of a kind of failed disciplinary effort in Tennessee that I think shows the challenges for accountability from the bar.

We hear about racial profiling from police, but in your reporting, have you come across profiling when it comes to sentencing or being charged with crimes?

Well, there’s definitely racial disparity built into charging and plea bargaining offenses, and studies have shown that at every step along the way, African American defendants get worse deals for similar conduct. So yes.

Right. But, is it something we’re not quite as aware of?

Yeah. I think in general, the police, we all see the police in the streets. They wear uniforms. Judges also wear a kind of uniform. Right? They wear a robe. They’re very visible icons of justice, but prosecutors are just lawyers wearing suits and I think the things they do tend to be more hidden and more veiled in the kind of density and abstract nature of law. It’s complicated to understand all the legal interpreting of what they’re up to. So, I think that they’ve gone relatively unnoticed in the picture of how American justice has changed.

You write about how important bail can be, that it can shape the outcome of a criminal case. But we currently have a private bail industry that you argue is in need of reform. Can you explain what’s wrong?

The United States and the Philippines are the only two countries in the world that allow for-profit cash bail — so we’re outliers. But our whole system of what happens to you after you’re charged, but before you’re convicted, depends on paying bail in most states in the country. So, you get charged with a crime, you go before a judge. The judge can let you out, called getting released on your own recognizance, or they can set bail in some amount. For many crimes in many places, judges set bail.

If you can’t pay, then you’re being detained because you don’t have enough money. To me, when I think about it that way, it starts to seem very strange. That it’s really money rather than public safety or the risk of failing to appear in court that’s driving the system. Even if you set high bail because of public safety or a failure to appear, it is still true that people who are wealthy are more likely to get out than people who don’t have money.

Right. But some states, like Kentucky, have outlawed cash bail. And there’s actually evidence that people will generally return to court even if they haven’t paid the bail. Right?

Exactly. Kentucky and Washington, D.C., especially have had systems for decades where there’s a small fraction of people who are held in jail because they’re deemed to be a public safety threat, and then everybody else gets out and almost all of those people come back to court without putting any money down — which really shows us that our for-profit cash bail system is not necessary.

Study after study shows that people who are being held in jail, pre-trial, because they can’t afford bail, are more likely to plead guilty.

How is bail part of a kind of domino effect that can start to impact the way a whole case might go?

Study after study shows that people who are being held in jail, pre-trial, because they can’t afford bail, are more likely to plead guilty. And when you think about it, it’s pretty logical. If you want to go home, you have an incentive to just sign the paper. Okay, it’s a lower offense. I’m getting a deal from the prosecutor. Maybe I did it. Maybe I didn’t. I just want to go home.

It really zaps people’s willingness or desire or endurance to fight charges. If you think of, in a more simple sense, the purpose of bail and holding people pre-trial, it’s really to keep the wheels of the system turning, because plea bargains — and especially quick plea bargains — save everybody a lot of time and work. Meaning the lawyers and the judges.

And the bail companies also sometimes do monitoring and surveillance as well, right?

Yeah. We’re putting ankle bracelets on people when they’re out pre-trial to make sure they come back. In some states, they’re monitored by the court system, but it is true. There are privatized companies that are also providing pre-trial services. Then you have a way in which we’re turning another aspect of the system into a for-profit enterprise.

You write about the impetus to “keep guns off the street,” which I think many people would get on board with, in order to reduce crime and mass shootings. But do you see an unintended consequence of this goal?

Yeah. I do. I think that when liberals support gun control, we usually think of the importance of like tightening the loopholes for who can buy a gun and requiring permits. There are lots of reasons to support gun permitting, and evidence that it can reduce gun violence. But I don’t think we think enough about the other side of the coin — which is when someone doesn’t have a permit, then what happens?

In most states, or in many states, we fine those people. But, there are a few states like New York that have these very harsh prison sentences for possessing a gun even if you don’t have a criminal record. Even if you didn’t threaten anyone with that gun. First of all, you can see all the racial disparity it leads to. These are laws that are enforced in poor black neighborhoods. Predominantly black communities definitely want public safety and they want good policing and they don’t want guns, but they also want things like social services that we’ve shown prevent crime.

But, instead, we put people in prison. There’s this useful framework that comes from my friend James Foreman, who’s a Yale Law Professor who talks about these predominantly black neighborhoods getting the worst of both worlds. Both having the threat from the guns and then also having the solution be prison, as opposed to something that changes the circumstances of people’s lives and gives them a reason to not have guns that is different from being incarcerated.

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

Sign up

And jail before trial is associated with more future risk of crime. Not less. Right?

Exactly. So, again, in New York, you send young black men to prison for two or three years for owning a gun. They’re all gonna come back after that time and they’re gonna be less employable. They’re gonna have problems getting back into public housing if that’s where they live. It’s just, in my view, a destructive way of dealing with the issue. It’s a real issue, but what’s the response that really makes sense?

So, you talked earlier about how few cases actually make it to trial — but isn’t there a lot of bias in trials as well? In witness testimony and unreliability of memory? Do you think there would be better outcomes if there were more trials instead of plea bargains?

Well, I think there’s two different things going on there. You’re right about eyewitness testimony and the reasons we have to doubt that sometimes and to really make sure that we have these procedures in place that don’t lead people to make mistakes in identification. Making sure that lineups are really blind and that the police don’t take their hand when they show someone a bunch of photoshoots about who they think the suspect is. It is totally true we should regard against all that. At the same time, I think it would be better if we had more trials because that’s when the government really gets tested. If you never have any trials, then the cops and the prosecutors can get away with sloppiness or even breaking the law. Violating people’s constitutional rights — and they never get called on it.

For example, I’m working on a podcast right now that’s related to my book. One of the people in the podcast was arrested and there was a stop and frisk on video. So, I can see the cops stop him and the police report says that Turari’s gun was visible in his waistband. But when you look at the videos, Turari was wearing this baggy hoodie. There’s no way the police saw the gun. You can’t see the gun. So, maybe they had another reason to stop him. It’s possible someone tipped them off and told that he had a gun, but you’d want to get that tested at trial. The problem is, Turari was facing such a long prison sentence that rolling the dice on going to trial just becomes too scary. So, you take the plea deal.

Let’s switch gears and talk about the reform movement. You outlined two different approaches to reform in your book. Gonzales, who’s the consensus-builder and Krasner, the “barn burner.” Can you talk about how you see these approaches?

I don’t really think one is better than the other, because we just don’t know enough. They’ve neither of them been in office very long and in some cities, the barn burner model is gonna be necessary. You’re gonna come into and office where prosecutors who work there are hostile to the reformer who comes in and it’s hostile to the reformer who comes in, like a new CEO. Come into a company, you don’t have to keep everybody there. They’re not entitled to a lifetime sinecure, and if they’re not down with what you want to do, it makes sense to fire people. On the other hand, if you don’t need to do that, you have people who are supporting your vision, then that can work.

In Philadelphia, Larry Krasner came into a pretty hostile office, and in Brooklyn Eric Gonzales came into an office where, first of all, he was a career prosecutor so he knew everyone. And there was much more of a tradition of discretion with plea bargaining and trying to work with defense counsel, much more than in Philadelphia. Gonzales needed a survey and most of his lawyers said yeah, we support your vision, and so he has been able to make fewer changes and still start to get done what he wants to get done.

In a few years, when we look at these prosecutors’ records and use new yardsticks like reducing incarceration, and reducing racial disparity, and increasing diversion, or just having fewer cases, then we’ll be able to start drawing some conclusions about what’s more effective.

When people see the law as legitimate, they’re much more likely to abide by it and to help do things like solve crimes and be witness to these cases.

D.A.s have traditionally run unopposed, and incumbents have often won in the past. What’s changed in the last couple of years?

There were a few things. One is that there’s bipartisan support for a new kind of prosecutor, and this is partly just because this is something that becomes so costly, and this blew so far beyond necessary bounds, and I think a lot of fiscal conservatives are fed up with it.

And then, importantly, you have the Black Lives Matter movement, which starts out obviously with a main priority being police shootings of unarmed people, but then intersects with the civil rights groups, and starts to think okay, what can we really do to change the places we live in, and change the power structure? And electing the local district attorney in a city turns out to be a tangible thing that this movement can deliver to its constituents. These are local elections, you don’t need to have that many voters to change the person in the D.A.’s office. If you organize, this is a win. So you start to see that awareness leads to a lot of real grass roots, local surges.

Then the third element is the donor class. Some donors, like George Soros, have come in and really powered these local organizers by giving them money.

You write that there should be more of a balance of power between prosecution, defense, and judiciary. What would an even shift look like to you?

Well, I think there are two things. One is that state legislators could eliminate mandatory minimum sentences, and that would have a big impact in the defense, prosecutor, judge shift that we’re talking about.

And I also think prosecutors have to give up some of their own power, which is not something that people usually want to do. For example, prosecutors that share all the evidence as quickly as possible with the defense — that’s a way of trying to even the scales. A state can pass a law requiring that, and Texas has done that in the last few years. But prosecutors can also do that themselves, in their own offices.

For people who don’t know a lot about their local prosecutors, what are the important things to learn when they’re making a decision about voting?

That’s a great question. I think you want to ask which kinds of crimes does your prosecutor think area priority? Are they interested in, for example, increasing the rate of conviction for murders, which is of late 60%. Across the country we only solve 60% of the homicides. Or are they talking about being tough on people who possess marijuana, or jump the turnstile, or have a traffic violation, right? So where’s the priority in the office?

Do they think that mass incarceration is a problem? What are they interested in doing to address it? And how do they think race plays into this itself, and do they have concrete steps they want to take to try to prevent racial disparity and racism from affecting the work of their office? How do they talk about treating teenagers who have committed crimes or minor offenses, like do they believe in treating kids like kids or do they want to prosecute teenagers as adults? And another thing to ask is how they think that they can try to protect immigrants from detention or deportation by reducing charges in some cases?

Your voice comes through as an advocate for reform. Where do you stand with this balance between your journalism and advocacy?

That’s a great question. I don’t see myself as an advocate. What I mean by that is, it’s not my job to push for a particular outcome. It’s my job to report what I’m seeing, and help people make informed decisions about the kind of criminal justice system that is pragmatic and makes sense. I’m a pragmatist at heart, so my reporting always drives me, as opposed to trying to bend the facts to support some predetermined outcome.

I did end my book with 21 principles for new prosecutors because I think a lot of times books like this, it’s all about the problem and the stories are upsetting because they show the problem, and then you get to the end and you have this sense of despair. I didn’t want people to have that, especially at a moment when I actually think there’s a lot of optimism and a lot of very interesting thinking about how to change things.

So I wanted to put all of that out there to give readers a sense of exactly the question you asked. Okay, if you’re voting for a local D.A., how do you know that this person has a different, a new vision of the criminal justice system? I wanted to give people a way to answer that question. But I always see myself as a journalist and not an advocate.

How can we rethink our justice system to make it more fair?

I think that we’ve had this “tough on crime” set of assumptions for a long, long time. To counter it we need to rethink safety. Safety is always the goal, right? That everyone deserves to be safe, and communities want to be safe. The challenge is to argue and really show people that when people, and there’s evidence for this, when people see the law as legitimate, they’re much more likely to abide by it and to help do things like solve crimes and be witness to these cases.

I would argue that because our system has become so punitive, it’s lost the trust and legitimacy in the eyes of a lot of the people who are impacted by it. And if you could get it back, we would actually be safer. So showing people that safety and fairness are integral to each other, that is a really important role that these new prosecutors can play.

* * *

Hope Reese is a journalist based in Louisville, KY. Her work has been featured in The Atlantic, the Los Angeles Review of Books, the Village Voice, Vox, and other publications.

Editor: Dana Snitzky

0 notes

Text

Questioning the use of actuarial risk assessment tools at sentencing

Erin Collins has this notable new commentary at The Crime Report under the headline "The Perils of 'Off-Label Sentencing'." I recommend the piece in full, and here are excerpts:

Current criminal justice reform efforts are risk-obsessed. Actuarial risk assessment tools, which claim to predict the risk that an individual will commit, or be arrested for, criminal activity, dominate discussions about how to reform policing, bail, and corrections decisions. And recently, risk-based reforms have entered a new arena: sentencing.... Actuarial sentencing has gained the support of many practitioners, academics, and prominent organizations, including the National Center for State Courts and the American Law Institute. [see Model Penal Code: Sentencing § 6B.09]

This enthusiasm is, at first blush, understandable: actuarial sentencing seems to have only promise and no peril. It allows judges to identify those who pose a low risk of recidivism and divert them from prison. Society thus avoids the financial cost of unnecessarily incarcerating low-risk individuals.

And yet, this enthusiasm for actuarial sentencing ignores a seemingly crucial point: actuarial risk assessment tools were not developed for sentencing purposes. In fact, the social scientists who developed the most popular risk assessment tools specified that they were not designed to determine the severity of a sentence, including whether or not to incarcerate someone. Actuarial sentencing is, in short, an “off-label” application of actuarial risk assessment information.

As we know from the medical context, the fact that a use is “off-label” does not necessarily mean it is ill-advised or ineffective. And, indeed, many contend that actuarial sentencing is a simple matter of using data gleaned in one area of criminal justice and applying it to another. If we know how to predict recidivism, why not use that information broadly? Isn’t this a prime example of an approach that is smart — rather than tough — on crime?

As I contend in my article, Punishing Risk, which is forthcoming in the Georgetown Law Journal this fall, the practice of actuarial sentencing is not that simple, nor is it wise. In fact, using actuarial information in this “off-label” way can cause an equally unintended consequence: it can justify more, not less, incarceration — and for reasons that undermine the fairness and integrity of our criminal justice system.

The actuarial risk assessment tools that are being integrated into sentencing decisions, such as the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) tool, and the Level of Services Inventory-Revised (LSI-R), were designed to assist corrections officers with a specific task: how to administer punishment in a way that advances rehabilitation. They are intended to be used after a judge has announced the sentence. They are based on the Risk-Need-Responsivity principle, according to which recidivism risk is identified so that it can be reduced through programming, treatment and security classifications that are responsive to the individual’s “criminogenic needs” (recidivism risk factors that can be changed).

Sentencing judges, in contrast, do not administer punishment but rather determine how much punishment is due. In doing so, they may use actuarial risk predictions to advance whatever punishment purpose they deem appropriate. While they may decide to divert a low-risk individual from prison in order to increase their rehabilitative possibilities, they may also decide to sentence a high-risk individual more harshly — not because doing so will increase her prospects of rehabilitation, but because it will increase public safety....

The tools measure risk based on a range of characteristics that are anathema to a principled sentencing inquiry, such as gender, education and employment history, and family criminality. Perhaps consideration of these factors makes sense if the predictive output is used to administer punishment in a way that is culturally competent and individualized.

But in the sentencing context, it allows the judge to punish someone more harshly based on a compilation of characteristics that are inherently personal and wholly non-culpable, and often replicate racial biases that pervade other areas of the criminal justice system. In other words, actuarial sentencing allows judges to defy the well-established tenet that we punish someone for what they did, not who they are....

Incorporating these tools into sentencing conflates recidivism risk, broadly defined, with risk to public safety. If we want to reduce our reliance on public safety, we must refine—rather than expand — the risk that counts for sentencing purposes.

Some of many prior related posts with links to articles and commentary on risk assessment tools:

"Punishing Risk"

"Principles of Risk Assessment: Sentencing and Policing"

"Assessing Risk Assessment in Action"

"Moneyball Sentencing"

"Adventures in Risk: Predicting Violent and Sexual Recidivism in Sentencing Law"

"The Use of Risk Assessment at Sentencing: Implications for Research and Policy"

"In Defense of Risk-Assessment Tools"

"Risk and Needs Assessment: Constitutional and Ethical Challenges"

"Under the Cloak of Brain Science: Risk Assessments, Parole, and the Powerful Guise of Objectivity"

0 notes

Text

How Teaching Using Mindfulness or Growth Mindset Can Backfire

Art Markman is an expert on what makes people tick. The psychology professor at UT Austin has also become a popular voice working to translate research from the lab into advice for a general audience. He’s co-authored popular books, including Brain Briefs Answers to the Most and Least Pressing Questions About Your Mind. He also writes a blog for Psychology Today magazine, and co-hosts a podcast through Austin’s NPR station called Two Guys on Your Head.

In his writings and podcasting, he’s tackled questions big and small, from commenting on the recent wave of mass shootings—to weighing in on why people like cat videos so much. And he’s full of surprising findings.

Take a recent blog post he wrote about mindfulness, for instance. Markman is not against meditation, and he agrees that taking steps to slow down and reflect without snap self-judgment can have benefits. But he also points out that such practices are not always universally positive. In a recent study done with prisoners, for instance, “the aspect of mindfulness associated with reserving judgment about the self actually increased criminogenic thinking significantly.” And even in a classroom setting, such practices are not helping creativity, according to research.

Markman recently talked with EdSurge about how his insights can help educators. He might just change the way you think about things like growth mindset, comprehensive testing, and encouraging students to make mistakes. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity. You can listen to a complete version below, or on your favorite podcast app (like iTunes or Stitcher).

EdSurge: Why do we humans seem to have so much trouble understanding ourselves? With all the advances in science, you'd think we'd have the human mind figured out a bit more.

Markman: First there’s the scientific question, shouldn't psychology be done by now? And the answer to that question is no. For one thing, psychology is a lot harder than almost any other science. I've often called cognitive science the place where Nobel laureates come to die. Somebody wins their Nobel prize in physics or chemistry and then says, "I'm gonna go fix cognitive science," and then they vanish without a trace. Because the brain is a complicated organ; it's embedded in social systems, in cultural systems, and it's constantly learning. So all of those factors make the mind and brain an extraordinarily difficult topic.

On top of that, as a science, we can't do all of the experiments we'd like to do because certain things are just unethical. You can't break people. You can split an atom; you can't split a person. You can't raise somebody in a closet so that they don't learn a language, right? So that also complicates the science.

Then there's a second half of the question, which is why is it that more people don't know more about psychology in ways that might help them to live their lives? It has to do with the fact that, when we systematized education about 120 years ago. We had to lay down a science curriculum, and the three mature sciences were biology, chemistry, and physics, so they made the cut. A lot of other sciences didn't, including psychology, which in the early 1900s barely wrested itself free of philosophy. And so we don't teach a lot of psychology.

On top of that, the structure of the brain makes it very hard for people to understand themselves well. Our motivational centers that drive a lot of our action are buried deep in the brain. They are brain structures that humans share with rats, mice and deer. All the complex reasoning and storytelling abilities that we have involve brain structures that are literally built on top of that other structure, and they don't have great access to what's going on in the motivational system. When people introspect, when they look inwards to try and understand their own behavior, they are actually telling stories about their own behavior that isn’t necessarily perfectly related to what actually drove that behavior, which is why people need to go into therapy. Because that introspection doesn't necessarily solve all your problems; sometimes you need a trained professional to help you to do it.

And so all of these factors combine to keep the brain a mystery, both to scientists and to everybody else.

One topic that you tackled recently on your blog that struck me is mindfulness. Even some colleges are trying it out as a way to help students. But you point out that research suggests mindfulness is not always positive. Could you talk a little bit about that?

As you say, mindfulness is a big trend these days, and there are a lot of great effects of mindfulness. And in particular, one of the things that mindfulness training can do is to make you more aware of some of your own thought processes and some of the emotional reactions you have to things in the world. And that is associated with better emotion regulation and greater likelihood of sticking with your long term goals. So I always like to preface this by saying I'm not making the argument that mindfulness is this a horrible thing that's being foisted on us. But I think we have to understand what it does and doesn't do. And so if you look at the research, there are a few areas where mindfulness is not helpful.

On the not helpful side is creativity. So you could ask the question, if you do a lot of mindfulness training, will you become a more creative individual? And the answer seems to be not so much; it doesn't seem to hurt, but it doesn't seem to help. What really helps you to become more creative is learning a bunch of stuff and having a wide, broad base of knowledge that you can draw from, and mindfulness isn't going to help you to get there.

You’ve written quite a bit about the concept of growth mindset. What is your take on that?

I've followed this work for a long time. Carol Dweck, who developed a lot of these ideas, she and I were colleagues together at Columbia University for a while before she went to Stanford and I came here to the University of Texas. I think there's a lot of wonderful stuff about this mindset work.

The concept is that you can think about almost any skill that you engage in as either being mostly talent-based or mostly skill-based; talent-based meaning, ‘I'm born with it,’ or skill-based meaning, ‘if I work hard enough at it, I'll get it.’ And what her work suggests is that if you adopt a growth mindset, which suggests that most things are skills, that you will often work harder in the face of adversity because you will recognize that your hard work will allow you to overcome difficulties. Whereas if you believe something is purely talent-based, then when things get difficult, you think, "Well, I guess I've reached the limits of my talent. I'm gonna give up."

And that can have important consequences with student retention?

I wrote about a study not long ago that was really interesting in which they looked at students in a low socioeconomic status school in India, and looked at providing information that would help students to adopt a growth mindset there. There were two findings there that I think should cause all of us who like this kind of work to take a step back and think about it more. And to be fair, Carol Dweck has acknowledged that this is part of her research program, so I'm not criticizing her particularly. But there were two findings of interest here: The first was that the students who were most helped by the growth mindset training were the best students already.

The second thing, though, was that for some of those students, particularly those students who the teachers acknowledged were the most conscientious students, this growth mindset training actually decreased their motivation to come to school. Giving them a growth mindset training actually increased their absentees. And the speculation in this paper was that, for some kids who grow up in poor neighborhoods, they come to school because they're good at it, and so they think there's something special about them that makes them good at this, and this is a place they can go to feel special. And when you give them growth mindset training, inadvertently what you do is to say, ‘Well, it's not really that you're special; it's that you've worked hard.’ And they're not as motivated by that as to be in a place where they were actually the special one, and so it actually undermined some of their motivation to continue to come to school.

And so what this means is that we need to really think carefully about how to take the controlled laboratory studies that we do in order to demonstrate that there's something worth continuing with, and then work hard to figure out what factors affect whether this is going to have an impact on students in ways that will help us to then launch this in a way that helps students, helps the students most in need, and doesn't undermine those students who might be succeeding on other grounds. This is no different than having laboratory studies that suggest a particular treatment might cure cancer, only to find out that it doesn't work as well when you try to use that in patients. So it's the hard work of applying research.

From all of your research and careful reading of the literature, what is your biggest piece of advice for teachers—something that might surprise them about how students learn?

What I would say is that we have a conflicting set of goals when we look at the educational system. On the one hand, we want to train independent, innovative thinkers, and then we want to do that by making sure that all of them get the same answer on the state test. And I think that one of the things we need to do is to really think about how the reward structure that is part of school influences the long-term thinking of students.

A lot of what we want to do is to give students more opportunities to do things that may not be correlated with grades, right? To give students opportunities to make mistakes and to recover from those mistakes—to give students opportunities to answer questions that nobody in the room knows the answer to, give students the opportunity to read stuff that has no bearing on whatever the lesson plan is at the moment. Because those skills in the long run are the ones that are correlated with success after school, and that to me is a real tension.

In the most recent book that you co-authored, Brain Briefs: Answers to the Most (and Least) Pressing Questions about Your Mind, one of the chapters is titled "Do Schools Teach the Way Students Learn?" What is your answer to that one?

I would say is sometimes, but often not.

One of the things that schools do is that they test on material at the end of units and then not again. And one of the things that we know about short term testing is that studying in the moment for a test that's coming up will allow you to learn the material for the test, but then your brain is basically gonna decide you don't need this information anymore if you don't encounter it again. Your brain wants to keep using information when you're forced to keep pulling it out over and over again. And so, even though students hate cumulative exams, those are the ones that actually force them to keep encountering the material repeatedly over the course of a year in order to make sure that it gets in there. So actually forcing them to keep going back to things that learned before in an explicit way is really important.

I think another part of what schools do, and this gets back to something I was saying a little bit earlier, is that schools teach mistake minimization, right? So to get good grades, you have to get the answers on each test correct, which means that the kids with the best grades, generally speaking, make the fewest mistakes. And what that teaches us is really good learning is about never making mistakes. But actually, learning is failure driven; it's when surprising things happen that you're forced to learn new things. And so it's actually the recovery from mistakes that helps people to learn best.

And so what we need to be teaching is yeah, make a mistake, but then you're responsible for fixing it and for understanding the thing you didn't understand. Getting a C is just the first step in a process of actually learning something, not the demonstration that you hadn't learned it.

We focus on technology in education, and these days there’s a lot of talk about trends like adaptive learning and flipped classrooms. How helpful do you think these types of tech innovations will be, or can a low-tech solution be more helpful?