#welding school near me in philadelphia

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Celebrating Success: Welding Technology Graduates Walk the Stage in Philadelphia

Witness the culmination of hard work and dedication as graduates from the Welding Technology program at the Philadelphia Technician Training Institute take their triumphant walk across the stage. From sparks to success, join us in honoring these skilled individuals as they embark on their promising futures.

#certified welder school in philadelphia#welding certification classes in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#welding school philadelphia#welding classes philadelphia#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#welding philadelphia#welding career in philadelphia#Youtube

0 notes

Text

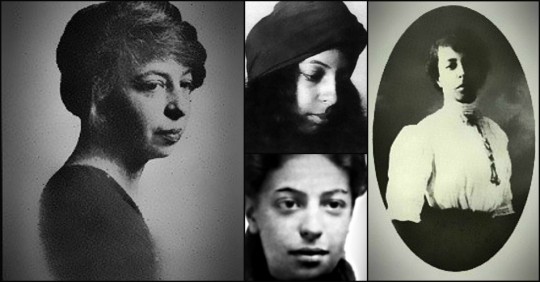

Angelina Weld Grimké

Angelina Weld Grimké (February 27, 1880 – June 10, 1958) was an American journalist, teacher, playwright and poet who came to prominence during the Harlem Renaissance. She was one of the first Woman of Colour/Interracial women to have a play publicly performed.

Life and career

Angelina Weld Grimké was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1880 to a biracial family. Her father, Archibald Grimké, was a lawyer and also of mixed race, son of a white planter. He was the second African American to have graduated from Harvard Law School. Her mother, Sarah Stanley, was European American from a Midwestern middle-class family. Information about her is scarce.

Grimké's parents met in Boston, where he had established a law practice. Angelina was named for her father's paternal white aunt Angelina Grimké Weld, who with her sister Sarah Grimké had brought him and his brothers into her family after learning about them after his father's death. (They were the "natural" mixed-race sons of her late brother, also one of the wealthy white Grimké planter family.)

When Grimké and Sarah Stanley married, they faced strong opposition from her family, due to concerns over race. The marriage did not last very long. Soon after their daughter Angelina's birth, Sarah left Archibald and returned with the infant to the Midwest. After Sarah began a career of her own, she sent Angelina, then seven, back to Massachusetts to live with her father. Angelina Grimké would have little to no contact with her mother after that. Sarah Stanley committed suicide several years later.

Angelina's paternal grandfather was Henry Grimké, of a large and wealthy slaveholding family based in Charleston, South Carolina. Her paternal grandmother was Nancy Weston, an enslaved woman of mixed race, with whom Henry became involved as a widower. They lived together and had three sons: Archibald, Francis and John (born after his father's death in 1852); they were majority white in ancestry. Henry taught Nancy and the boys to read and write. Among Henry's family were two sisters who had opposed slavery and left the South before he began his relationship with Weston; Sarah and Angelina Grimké became notable abolitionists in the North. The Grimkés were also related to John Grimké Drayton of Magnolia Plantation near Charleston, South Carolina. South Carolina had laws making it difficult for an individual to manumit slaves, even their own children born into slavery. Instead of trying to gain the necessary legislative approval for each manumission, wealthy fathers often sent their children north for schooling to give them opportunities, and hoping they would stay to live in a free state.

Angelina's uncle, Francis J. Grimké, graduated from Lincoln University, PA and Princeton Theological Seminary. He became a Presbyterian minister in Washington, DC. He married Charlotte Forten. She became known as an abolitionist and diarist. She was from a prominent family of color in Philadelphia who were strong abolitionists.

From the ages of 14 to 18, Angelina lived with her aunt and uncle, Charlotte and Francis, in Washington, DC and attended school there. During this period, her father was serving as US consul (1894 and 1898) to the Dominican Republic. Indicating the significance of her father's consulship in her life, Angelina later recalled, "it was thought best not to take me down to [Santo Domingo] but so often and so vivid have I had the scene and life described that I seem to have been there too."

Angelina Grimké attended the Boston Normal School of Gymnastics, which later developed as the Department of Hygiene of Wellesley College. After graduating, she and her father moved to Washington, D.C. to be with his brother Francis and family.

In 1902, Grimké began teaching English at the Armstrong Manual Training School, a black school in the segregated system of the capitol. In 1916 she moved to a teaching position at the Dunbar High School for black students, renowned for its academic excellence, where one of her pupils was the future poet and playwright May Miller. During the summers, Grimké frequently took classes at Harvard University, where her father had attended law school.

Around 1913, Grimké was involved in a train crash which left her health in a precarious state. After her father took ill in 1928, she tended to him until his death in 1930. Afterward, she left Washington, DC, for New York City, where she settled in Brooklyn. She lived a quiet retirement as a semi-recluse. She died in 1958.

Literary career

Grimké wrote essays, short stories and poems which were published in The Crisis, the newspaper of the NAACP, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois; and Opportunity. They were also collected in anthologies of the Harlem Renaissance: The New Negro, Caroling Dusk, and Negro Poets and Their Poems. Her more well-known poems include "The Eyes of My Regret", "At April", "Trees" and "The Closing Door". While living in Washington, DC, she was included among the figures of the Harlem Renaissance, as her work was published in its journals and she became connected to figures in its circle. Some critics place her in the period before the Renaissance. During that time, she counted the poet Georgia Douglas Johnson as one of her friends.

Grimké wrote Rachel – originally titled Blessed Are the Barren – one of the first plays to protest lynching and racial violence. The three-act drama was written for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which called for new works to rally public opinion against D. W. Griffith's recently released film, The Birth of a Nation (1915), which glorified the Ku Klux Klan and portrayed a racist view of blacks and of their role in the American Civil War and Reconstruction in the South. Produced in 1916 in Washington, D.C., and subsequently in New York City, Rachel was performed by an all-black cast. Reaction to the play was good. The NAACP said of the play: "This is the first attempt to use the stage for race propaganda in order to enlighten the American people relating to the lamentable condition of ten millions of Colored citizens in this free republic."

Rachel portrays the life of an African-American family in the North in the early 20th century. Centered on the family of the title character, each role expresses different responses to the racial discrimination against blacks at the time. The themes of motherhood and the innocence of children are integral aspects of Grimké's work. Rachel develops as she changes her perceptions of what the role of a mother might be, based on her sense of the importance of a naivete towards the terrible truths of the world around her. A lynching is the fulcrum of the play.

The play was published in 1920, but received little attention after its initial productions. In the years since, however, it has been recognized as a precursor to the Harlem Renaissance. It is one of the first examples of this political and cultural movement to explore the historical roots of African Americans.

Grimké wrote a second anti-lynching play, Mara, parts of which have never been published. Much of her fiction and non-fiction focused on the theme of lynching, including the short story, "Goldie." It was based on the 1918 lynching in Georgia of Mary Turner, a married black woman who was the mother of two children and pregnant with a third.

Sexuality

At the age of 16, Grimké wrote to a friend, Mary P. Burrill:

I know you are too young now to become my wife, but I hope, darling, that in a few years you will come to me and be my love, my wife! How my brain whirls how my pulse leaps with joy and madness when I think of these two words, 'my wife'"

Two years earlier, in 1903, Grimké and her father had a falling out when she told him that she was in love. Archibald Grimké responded with an ultimatum demanding that she choose between her lover and himself. Grimké family biographer Mark Perry speculates that the person involved may have been female, and that Archibald may already have been aware of Angelina's sexual leaning.

Analysis of her work by modern literary critics has provided strong evidence that Grimke was lesbian or bisexual. Some critics believe this is expressed in her published poetry in a subtle way. Scholars found more evidence after her death when studying her diaries and more explicit unpublished works. The Dictionary of Literary Biography: African-American Writers Before the Harlem Renaissance states: "In several poems and in her diaries Grimké expressed the frustration that her lesbianism created; thwarted longing is a theme in several poems." Some of her unpublished poems are more explicitly lesbian, implying that she lived a life of suppression, "both personal and creative.”

Wikipedia

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Should We Be Afraid of the Mariner East Pipeline?

City

The ongoing battle over the project is taking place in the backyards of Chester and Delaware county residents, who live in fear of a catastrophe.

Exton’s Paula Brandl and the Mariner East Pipeline construction barricade cutting through her backyard. Photograph by Shira Yudkoff

It was dark outside, around 5 a.m., when the flames took over the sky. Neighbors described it like this: a loud hissing noise. A massive ball of fire. A jet, or a meteor, crashing into the earth. Night turning into day.

On September 10, 2018, a section of the Revolution Pipeline — which had begun carrying natural gas just a week earlier — leaked and ignited in rural Beaver County, Pennsylvania, northwest of Pittsburgh. The rupture shot flames 150 feet into the air, destroying one house, collapsing several overhead power lines, and forcing the evacuation of nearly 50 residents.

Fortunately, no one was injured; the couple who lost their home had fled in the nick of time.

But for residents living along the thousands of miles of natural gas pipelines in Pennsylvania — second only to Texas as the nation’s largest producer of the fossil fuel and home to the newly booming, energy-rich Marcellus Shale region — the fire and the charred earth it left behind serve as a haunting reminder: Something like this could happen in our backyards.

That dread is perhaps nowhere more evident than 300 miles southeast of Beaver County, in the dense suburban neighborhoods west of Philadelphia, a city that energy industry leaders have, in the past decade, eyed as a global processing and trading hub. Here, tensions surrounding the cross-state Mariner East pipelines — a project much larger than Revolution and owned by the same parent company, Dallas-based Energy Transfer — are only intensifying.

The pipelines (Mariner East 1 and 2 and the not-yet-completed 2x) carry highly compressed natural gas liquids. Once they are fully operational along a 350-mile route from their Marcellus Shale source to a revitalized former oil refinery in Marcus Hook, they promise to be vastly lucrative for Energy Transfer — and for the state, which, the company boasts, could see an economic impact of more than $9 billion from the project. But since work began in February 2017, Mariner East has been plagued by nearly 100 state Department of Environmental Protection violations, multiple sinkholes, service shutdowns and construction chaos. Glaring gaps in state regulatory oversight have been exposed, and opposition has grown into significant pushback from neighbors and a bipartisan group of lawmakers who say Pennsylvania communities are at risk of — and unprepared for — a potential pipeline disaster.

Mariner East is headed for an inflection point: Construction could continue despite opponents’ pitched efforts, or officials could take steps to pause, end or remedy a project that’s been embattled since its inception. In the meantime, those at the heart of the Mariner East conflict zone live in fear of an incident like Beaver County’s — or worse.

•

In April, a fortress-like metal barricade was erected across the center of Paula Brandl’s quiet, grassy backyard in Exton, Chester County. The scene outside her kitchen window is almost dystopian. Brandl says land agents connected with Sunoco Pipeline LP, the Energy Transfer subsidiary that’s building the lines, told her the wall was installed as a noise barrier. For roughly two weeks after it went up, she says, she and her family members were “in shock.” Brandl contacted the agents and various state agencies to inquire about vibrations caused by the hidden construction as well as diesel exhaust in the air in and around her home, but she says no one she spoke with was helpful or informative.

“I have every right to know what is going on back there,” Brandl says at her dining room table one late-April day. “It’s just as if I don’t even own that land anymore.”

Energy Transfer is able to occupy Brandl’s backyard (and yards in 17 Pennsylvania counties) through what a recent New Yorker story termed a “legal loophole” linking the Mariner East project to the route of a 1930s pipeline that formerly transported heating oil. The Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission, the main state agency tasked with overseeing oil and gas projects, has deemed the project a public utility, stressing that state code “recognizes the intrastate transportation by pipeline of petroleum products.” Doing so grants the pipelines right-of-way, which is typically reserved for utilities offering some sort of benefit to the general public, like schools or highways.

Energy Transfer spokesperson Lisa Dillinger says that putting additional pipelines into an existing right-of-way is a common practice that “helps to reduce our environmental footprint.” But the pipelines’ public utility status enrages Brandl and other residents, especially since a significant quantity of the product the lines carry is to be shipped overseas to make plastics.

“The PUC failed us,” Brandl says. “This is not a utility. This is not a gas line that’s serving the benefit of Pennsylvanians. And that’s basically the root of this entire issue.”

In Pennsylvania, there’s no state agency responsible for approving the routes of intrastate hazardous-liquid pipelines — nor does federal law require that oversight. David Hess, who served as Pennsylvania’s DEP secretary under Republican governors Tom Ridge and Mark Schweiker from 2001 to 2003, says the lack of any such authority puts Pennsylvania “in a very disadvantageous position … because the pipeline route is critical. If the law was different, I don’t think you’d ever approve a route through populated areas like these, given the risks with some of these materials being carried.”

Dillinger says that Energy Transfer goes “above and beyond what is required to ensure the safety of our lines.” But it’s clear that the state agencies left to regulate the massive Mariner East project — the Pennsylvania DEP and the PUC — have an unprecedented situation on their hands, with what Hess calls “unanticipated impacts” in areas “overgrown with development.” Chief among those impacts are sinkholes that have opened in yards along the pipeline construction route in Chester County, twice exposing the buried pipe of the 1930s line (now repurposed as Mariner East 1) and prompting pipeline shutdowns to avert what the PUC called a potentially “catastrophic” risk to public safety.

The residents who owned those once-quaint yards — on Lisa Drive, just outside Exton — said they were terrified for their lives. Then, in April, Energy Transfer bought two of the homes, and the families moved out. Now, the properties sit eerily quiet and mostly empty, save for construction equipment and a small sign in one of the yards: notice: audio and video recording in progress. When I visited the area in early May, a man who identified himself as a relative of one of the former homeowners told me that in the neighborhood, “Everybody wants to get out.”

•

Paula Brandl and other residents who have endured the complications of hosting Mariner East construction on or near their properties — water contamination, spills of drilling mud, intimidating contractors — say those side effects pale in comparison to their biggest fear: a pipeline leak.

Natural gas liquids can rapidly change to an explosive gaseous state during a leak, and the gas can be ignited by sources as small as static discharge from using a cell phone, flicking a light switch or ringing a doorbell. Leaks, which can be caused by welding failures, material defects, pipeline corrosion, shifting land and other factors, have already happened along Mariner East 1 — three since 2014, though none resulted in an explosion. Energy Transfer’s Dillinger says the 88-year-old pipeline underwent “integrity testing and major upgrades” when it was repurposed for natural gas liquids service, and in April, two years after a high-profile leak in Berks County, the company said it would conduct a “remaining life study” of the line.

Energy Transfer’s safety record is, however, bleak in general. Between 2002 and the end of 2017, pipelines affiliated with the company across the country experienced a leak or an accident every 11 days on average, according to an analysis of federal pipeline data compiled by environmental advocacy organizations Greenpeace USA and Waterkeeper Alliance. In an evaluation by NPR affiliate StateImpact Pennsylvania, the same federal data showed that Sunoco Pipeline is responsible for the industry’s second-highest number of incidents reported to inspectors over the past 12 years.

“When it comes to number of accidents, Sunoco’s not just an outlier; they’re sort of an extreme outlier,” Eric Friedman, a Delaware County resident who lives steps from the Mariner East pipeline route, tells me. Friedman, a former airline pilot who has worked for the FAA since 2006, sees Mariner East through a risk-management lens. (“Everything we do in commercial aviation is based on risk,” he says.) He learned of the pipelines in 2013 — a year after buying his home in an affluent Glen Mills neighborhood — and has been researching the project ever since. He’s in regular contact with the offices of lawmakers like U.S. Rep Mary Gay Scanlon and Chester County State Senator Andy Dinniman — the politician widely considered to be the pipelines’ most vocal opponent — and he’s one of the leaders of a nonpartisan residents group called the Middletown Coalition for Community Safety. In November 2018, seven residents of Chester and Delaware counties filed a complaint with the PUC against Sunoco Pipeline LP, alleging that the subsidiary hasn’t provided the public with a sufficient emergency notification system or management plan in the event of a pipeline-related disaster. The petitioners (nicknamed by residents the “Safety 7”) argue that as a public utility operator, Sunoco is tasked by federal regulations enforced by the PUC with providing an emergency-preparedness plan for potential disasters, like a possible leak along the Mariner East route. The failure to release a satisfactory plan, they say, places residents in the pipelines’ blast zone “at imminent risk of catastrophic and irreparable loss, including loss of life, serious injury to life, and damage to their homes and property.”

Energy Transfer has disputed the residents’ claims, saying that its emergency-response professionals “work and train with local first responders” and that it has shared a written public-education program specific to the area with emergency-response professionals along the line. Still, residents say the company hasn’t sufficiently involved the public in its preventative plans; the complaint is scheduled for hearings before an administrative law judge in July.

Meanwhile, the PUC has said it won’t release information about the potential impact of a leak or an explosion for several reasons, including that the state’s Right to Know law prohibits the disclosure of records that are “reasonably likely to jeopardize or threaten public safety.” Sharing the hazard assessments, the PUC argues, could compromise pipeline security by revealing information “which could clearly be used by a terrorist to plan an attack … to cause the greatest possible harm and mass destruction to the public living near such facilities.”

Brandl and other residents stress that living next to a “mass destruction” target is terrifying, with or without a disaster plan. To make matters worse, a recent report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found major weaknesses in how the Department of Homeland Security’s Transportation Security Administration — which is responsible for addressing terrorism risks along the nation’s 2.7 million miles of oil and gas pipelines — manages its pipeline security efforts.

“I don’t think I’d be living 25 feet away from that pipeline,” Hess, the former DEP secretary, says. “But again, the question is, why was someone allowed to live within 25 feet of this pipeline in the first place?”

•

In December, Chester County District Attorney Tom Hogan announced a criminal investigation into conduct related to the Mariner East project, saying that potential charges against individual Energy Transfer employees or corporate officers could include causing or risking a catastrophe, criminal mischief and environmental crimes. More recently, Delaware County DA Katayoun Copeland and Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro launched a joint investigation into Sunoco Pipeline LP and Energy Transfer over allegations of criminal misconduct related to the project, with Copeland stating that there “is no question that the pipeline poses certain concerns and risks to our residents.” (At press time, both investigations were ongoing.) Energy Transfer’s Dillinger says that the company remains “confident that we have not acted to violate any criminal laws in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and are committed to aggressively defending ourselves.”

After years of pressure, residents might finally be getting through to the state. At a Pennsylvania Senate committee meeting in June 2018 — before, even, a number of critical developments regarding Mariner East — former Republican State Senator Don White of Indiana County made a surprising statement: If issues raised at the committee’s meetings regarding pipeline safety consistently involve one project — referring to Mariner East — then “we have the ability in this state to find a way to deal with this company and put them out of business.”

David Hess, the former Republican DEP secretary — he was also executive director of the state Senate Environmental Resources and Energy Committee in the ’90s — says that for a “Republican senator to say that is astounding … [it] really underscores the problems this company is generating.”

As frustration and fear about Mariner East spread to constituents in red and blue districts alike, lawmakers who are typically supportive of the oil and gas industry (like north-central Pennsylvania State Senator Gene Yaw) are voicing concern. White’s proposition poses a question that residents are forcing officials — particularly Governor Tom Wolf, who has positioned himself as an ally to environmentalists and residents but has received tens of thousands of dollars in donations from oil and gas industry affiliates — to consider: How should they deal with the Mariner East pipelines?

Several months after the Revolution Pipeline incident in Beaver County, Wolf released a statement calling on state lawmakers to “address gaps in existing law which have tied the hands of the executive and independent agencies charged with protecting public health, safety and the environment.” His suggestions included giving the PUC authority over the routing of intrastate pipelines, ordering companies to work with local emergency coordinators, and requiring the installation of remote shutoff valves to contain leaks. But the GOP-dominated legislature has yet to move any bills that would allow for those reforms. And none of that changes the fact that Mariner East has been unfolding on Wolf’s watch. The Governor has yet to visit Delaware or Chester counties to speak firsthand with residents living near the pipelines about their experiences. (Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman visited before the 2018 primary; a spokesman for Wolf’s office said the Governor has met with residents and lawmakers about the project in Harrisburg.) Constituents say Wolf is simply not doing enough to prevent a potential disaster. Whether his administration will adopt a firmer stance toward Mariner East — as residents and local lawmakers have requested — remains uncertain.

Meanwhile, the project continues to highlight the limitations of both the DEP and the PUC. After all, there were warning signs before the Beaver County leak, which Energy Transfer has said resulted from a landslide that followed heavy rains. (Both the company and the PUC are still investigating the incident.) The DEP had fined Energy Transfer three months before the Revolution Pipeline explosion for failing to mitigate erosion on a hillside about a mile from the site; the DEP says that at the time, it was “unaware of the issues associated with the blast site.” Critics have also questioned the agency’s decision to allow Sunoco Pipeline to use relatively new and potentially disruptive drilling methods that geologists say may have increased the risk of sinkholes along Lisa Drive in Chester County. The PUC and state DEP have penalized Energy Transfer for many of the company’s missteps, at times (and increasingly) seriously. Revolution Pipeline remains out of service, and since February, the DEP has suspended all Energy Transfer permit applications (including for Mariner East) until the company reaches compliance in Beaver County. To Hess, the agencies are “working in the best way they can.” But, he argues, lawmakers need to consider more stringent regulation, especially of pipeline routes.

The question for residents is whether officials or Energy Transfer will act before an emergency. Until then, Eric Friedman says, they’ll continue to feel unprotected.

“I think at some level, the most important function of government is to reasonably provide for the public’s safety,” he says. “And how can you have a project like this, that could kill hundreds or thousands of people in the worst-case scenario, and hope for the best and not plan for the worst?”

Published as “What Lies Beneath” in the July 2019 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Source: https://www.phillymag.com/news/2019/07/06/mariner-east-pipeline-sunoco-pennsylvania/

0 notes

Text

Welding Job Search In The US: How To Boost Your Job Search

Discover practical strategies to enhance your welding job search in the US. From certifications to networking, unlock valuable tips for success in the welding industry.

#best welding trade schools in philadelphia#certified welder school in philadelphia#welding certification classes in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#welding school philadelphia#welding classes philadelphia#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#welding philadelphia

0 notes

Text

Does A Welding Program Teach Apprentices To Use A TIG Welding Machine?

Explore how a welding program equips apprentices with TIG welding skills. Gain proficiency in this versatile technique for a successful welding career.

#welding school philadelphia#welding classes philadelphia#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#welding philadelphia#welding career in philadelphia#welding tech institute in philadelphia#welding Technician certification programs in philadelphia#welding trade schools degree in philadelphia#welding Technician certification classes in philadelphia

0 notes

Text

youtube

Turning Passion into Career: Welding Training in Philadelphia

Welding Training in Philadelphia help apprentices transform thier passion into career. Learn with PTT how you can mold metals and craft your future

#certified welder school in philadelphia#welding certification classes in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#welding school philadelphia#welding classes philadelphia#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#Youtube

0 notes

Text

youtube

Discover excellence in welding education at PTTI. Our specialized programs offer hands-on experience, expert guidance, and cutting-edge techniques, propelling you towards a successful career in the world of welding. Dive into the art and science of metalwork with us.

#best welding trade schools in philadelphia#certified welder school in philadelphia#welding certification classes in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#welding school philadelphia#welding classes philadelphia#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#welding philadelphia#welding career in philadelphia#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Unlock opportunities with a modern welding course. With welding training, gain tech skills, diversify your career, and stay ahead in the world of welding.

#certified welder school in philadelphia#welding certification classes in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#welding school philadelphia#welding classes philadelphia#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#welding philadelphia#welding career in philadelphia

0 notes

Text

youtube

Crafting Expertise: Comprehensive Welding Training at PTTI

Explore the art of welding with our comprehensive training program at PTTI. Gain hands-on experience, learn cutting-edge techniques, and master the skills needed for a thriving career in welding. Our industry-leading instructors and state-of-the-art facilities ensure you're equipped to excel in this in-demand field. Join us to forge a path toward expertise and success in welding.

#welding certification classes in philadelphia#welder training school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#welding school philadelphia#welding classes philadelphia#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#welding philadelphia#welding career in philadelphia#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Explore welding programs, classes, and the path to a thriving career. Ignite your journey with expert training and hands-on learning.

#welding school philadelphia#welding classes philadelphia#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#Welding Trade Programs in Mantua#welding certification training Institute in Mantua#welding course in Mantua#welding trade School in Mantua#Welding Trade Programs in powelton Village#welding certification training Institute in powelton Village#welding course in powelton Village#welding trade School in powelton Village

0 notes

Text

youtube

At PTTI's welding training, craftsmanship meets precision. Artistry ignites in every weld as skills ascend to new heights. Students sculpt metal with finesse, mastering the fusion of technique and creativity. Each spark signifies the elevation of expertise, forging artisans poised to craft brilliance in every molten seam.

#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#welding philadelphia#welding career in philadelphia#welding course in haverford North#welding trade School in haverford North#Welding Trade Programs in West Powelton#welding certification training Institute in West Powelton#welding course in West Powelton#welding trade School in West Powelton#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Welding Repair Guide Techniques For Perfect Welds

Explore effective troubleshooting techniques in our welding repair guide. Fix common repair issues with expert insights and tips to get that perfect weld.

#welding course in South West Philadelphia#welding trade programs in Allegheny West#welding trade school in Allegheny West#welding certification training Institute Allegheny West#welding course in Allegheny West#welding trade programs in Broad street#welding trade school in Broad street#welding certification training Institute Broad street#welding course in Broad street#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#welding philadelphia#welding career in philadelphia

0 notes

Text

youtube

At PTTI, our welding training, guided by industry experts, ignites success. With hands-on instruction and cutting-edge techniques, students forge a path to mastery. Elevate your welding skills, embrace precision, and enroll in a program where expert guidance sparks the flames of success.

#Welding Trade Programs in Mill Creek#welding certification training Institute in Mill Creek#welding course in Mill Creek#welding trade School in Mill creek#Welding Trade Programs in haverford North#welding certification training Institute in haverford North#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#welding philadelphia#welding career in philadelphia#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Welding training now includes underwater welding work. Learn more about the technological advancements, innovations, and opportunities in underwater welding.

#types of welding#welding classes#welding class#welding companies#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia#welding philadelphia#welding trade School in Spring garden#Welding Trade Programs in Spring garden#welding certification training Institute in Spring garden#welding course in Spring garden#welding trade School in Wynnfield Heights

0 notes

Text

PTTI's Welding Training Program is a comprehensive guide to welding excellence. This expert resource empowers beginners and professionals alike, providing valuable insights and techniques to ignite their welding skills and achieve remarkable proficiency.

#welder training school in philadelphia#welding schools in philadelphia pa#welding school philadelphia#welding classes philadelphia#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#Welding Trade Programs in south philadelphia east#welding certification training Institute in south philadelphia east#welding course in south philadelphia east#Welding Trade Programs in south philadelphia west#welding certification training Institute in south philadelphia west

0 notes

Text

Welding training programs and experience are essential for professional welding work. Dive in to understand the importance of both in the welding industry!

#welding trade School in Gloucester City#NJ#Welding Trade Programs in Gloucester City#welding certification training Institute in Gloucester City#welding course in Gloucester City#welding trade School in Lansdowne#PA#Welding Trade Programs in Lansdowne#welding schools in philadelphia pa#welding school philadelphia#welding classes philadelphia#fabrication welding process in philadelphia#welding school near me in philadelphia#welder apprenticeship programs in philadelphia

0 notes