#we get transient orcas

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Rabid Seals

We didn’t know this could happen, we are worried about other marine animals. And not to be a sensationalist but someone call up Stephen King and ask him how he feels about the possibility of a rabid orca.

#rabies#rabid animals#marine mammals#pinnipeds#cape fur seals#seal colony#elephant seals#mustelidae#cape clawed otter#delphinidae#dolphins#porpoises#common dolphin#bottlenose dolphin#orca#south africa#southern africa#i was only half kidding about the orcas#we get transient orcas#they come to hunt the great white sharks#they are mammals#mammals can contract rabies#but we don’t know whether that extends to delphinidae#we didn’t even know pinnipeds could pick it up!#there was only one isolated incident in the world before this

1 note

·

View note

Note

About Acheron as a orca hybrid, it does seem right for her to be a transient orca!, however my question lays on, how would Vet! Reader feel about Acheron’s diet? Since orcas need lots of food to keep swimming and hunting they either need foods such as Sea lions, Elephant seals, penguins and even sometimes great white shark livers or TONS of fish to even get to the level of protein they need, they also require lots of ice if they are being kept in a pool for a designated time but would Vet! Reader feel icky about having to feed orca Acheron dead penguins and such?

Orcas are my biggest hyperfixation so seeing Orca mentions in here was a surprise!

In my Animal Hybrid AU, there are regular animals and hybrids that coexist in the world. Hybrids are your typical half human, half animal kind of species, and regular animals are self explanatory, as they’re the animals we have in the real world. Carnivorous hybrids are able to hunt regular animals for their diet, so when Vet! Reader goes to feed Orca! Acheron, she feeds her regular animals like fish, seal meat, etc. animals who aren’t hybrids are typically eaten by hybrids anyways.

The Vet does not feel guilty, carnivores need to eat meat so she feeds them meat. She just doesn’t feed Acheron any fish/seal/penguin hybrids for her own ethical morals. In the wild though, it should be noted that hybrids can hunt other hybrids as it’s not considered cannibalism for them. It’s mostly for dire survival situations that they will turn to other hybrids for meat, but they typically opt to feast on regular animals instead. Humans are also banned from consuming hybrids, they stick to eating regular animals.

Anyways to summarize everything, the Vet doesn’t feel guilty. Acheron can eat all the fish and meat she wants 😋

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been seeing Keferon’s Apocalyptic Ponyo AU around and it’s really hitting my brain. I can’t possibly get all my thoughts down rn, but seeing Jazz and Prowl as orcas/killer whales is so fun and raises some interesting questions.

My main question is this: Are they resident or transient whales? If they’re escaped aquarium whales, they’re most likely residents (rounded dorsal tip, primarily eat fish, highly vocal, stable pod groups), but they could also fit nicely as transient orcas (quieter with fewer dialects, small and fluid groups, prefer eating marine mammals, pointier dorsal fins and closed saddle marking). To be fair though, the behaviors that seem more like transient orcas could just be a result of captivity and neglect.

Here’s a rapid-fire of more questions because both orcas and mer AUs fascinate me (+ a Hakai Magazine infographic on resident/transient whales and a link better explaining things)

Do orca mers have distinct dialects in this AU, or can all mers communicate relatively easily regardless of place of origin, species, or culture? Would Jazz’s collapsed dorsal fin right itself a little after being freed (which can happen)? Would that even be considered that odd is orca mer culture, as dorsal fins can curl for a variety of reasons? Would they wear salmon hats like some of the pods we see today, or is that considered unfashionable? Has the inclusion of hands in orca anatomy created a completely new kind of dolphin deviousness or are they chill about it? The idea of any kind of orca, dolphin, or porpoise with hands seems like it spells trouble. Are orca mers the same length as regular orcas, or are they longer, as their humanoid and orca halves seem to connect around where a normal orca’s neck is? How deep can they dive?

I’m stopping myself there, but yeah! Orcas! Sea creatures! Transformers AUs! Thank you so much, Keferon!

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hope there's people doing research about this bc i am so intrigued. These are 3 different orcas Chimo, Tl'uk, and Frosty

They are all from the same population, west coast transients. Chimo was captured and known to have Chédiak–Higashi Syndrome. Tl'uk and Frosty were both wild and it's unknown if they have the same condition or if it's (only[?]) leucism. Chimo died when she was 4-5, probably partially because she was in captivity and because her condition weakened her immune system. Tl'uk died when he was about 3 by unknown causes but its presumed it might have also been because of a weakened immune system given his discoloration. Frosty is currently almost 6 and doing well and their sex is unknown. Chédiak–Higashi Syndrome is genetic. I wonder if any or all of them were related? We have one female and one male, depending on Frosty's sex I wonder if that is a factor to the likeliness of getting the disease or how it's passed down? And the most interesting to me, WHYYY do they all have the same pattern of being darker on their rostrums??? Could the patterning also be genetic? ALSO!!! There are no pictures of Chimo younger than 2 years old, but this is Tl'uk and Frosty when they were younger

THEYRE BOTH EVENLY GREY??? Why did they get lighter AND darker as they got older? SCIENTISTS!!! DISCUSS!!!!

#im slightly confused on the leucism point bc i read some things that said chimo's Chédiak–Higashi Syndrome caused leucism#like it was just an umbrella statement for lack of pigmentation ?#and some things that said leucism is its own separate disease#i mean i know leucism is a condition but i dont know much about Chédiak–Higashi Syndrome and is they're overlapping here or what#theres also something to be said about some white orcas in japan !!!#which im adding in the tags bc im much less familiar with them#but theres a few adult males that are also white. i believe for unknown reasons#but they're pretty evenly colored#and they're much more yellowish than grey like these 3#idk how many there are but i think most of them are males ? and adults#so maybe their immune system isnt comprised ?#i also saw smth about their population possibly being fairly inbred and that could be a factor too#idk. its so interesting!!!! why are they all darker on their heads!!!!!!!!#whales

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

DID YOU HEAR ABOUT THE NEW ORCA SPECIES

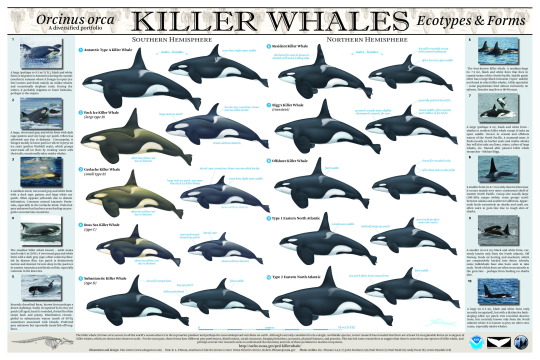

i'm assuming you're talking about the proposed distinction between resident and transient orcas? i had to check bc i hadn't actually seen that a decision had been made (i did see when the study came out a few months back so i knew it had been proposed) and it looks like they haven't actually been accepted as separate species but are for the moment being recognized as distinct subspecies. the society for marine mammalogy's list of marine mammal species and subspecies currently lists them like this:

Orcinus orca (Linnaeus, 1758). Killer whale, orca

O. o. ater (Cope in Scammon, 1869). Resident killer whale

O. o. orca (Linnaeus, 1758). Common killer whale

O. o. rectipinnus (Cope in Scammon, 1869). Bigg’s killer whale

and this is what the text says about it:

Based on genetic, morphological and ecological data, Morin et al. (2024) provided a taxonomic revision for two ecotypes of Orcinus orca in the eastern North Pacific: Bigg’s killer whale (also known as transient ecotype) and the resident killer whale. The level of differentiation observed led the authors to recommend their recognition as distinct species: O. rectipinnus (Bigg’s killer whale) and O. ater (resident killer whale). Although the majority of the voting members recognize the high level of differentiation between the two ecotypes in all the evidence presented in Morin et al. (2024), there was uncertainty whether this diagnosability represented species- or subspecies-level designation. Some points argued against species designation at the time included: 1) the nesting of both clades within the wider O. orca clade in the mitogenome phylogeny; 2) presence of episodic gene flow among the ecotypes, which needs further investigation; and 3) the need to conduct a more comprehensive analysis on a global context to better understand how distinct these two ecotypes are from other Orcinus orca clades, including those found at latitudes below ~34º N off the coasts of California and Mexico and the more northerly Bigg’s and offshore ecotypes, which were not evaluated in the paper. Previously, the Committee followed the recognition in Krahn et al. (2004) of two un-named subspecies of killer whales for the eastern North Pacific, which were listed in previous version of the List of Proposed Un-named Species and Subspecies. These two un-named subspecies correspond to the resident and Bigg’s/transient ecotypes, respectively. Therefore, pending a more complete global review and revision of the killer whales, the two ecotypes are considered here provisionally as distinct subspecies of Orcinus orca and named following Morin et al. (2024): O. orca ater (resident killer whale) and O. orca rectipinnus (Bigg’s killer whale), with O. orca orca (common killer whale) as the nominate subspecies.

it remains to be seen how everything shakes out after further research! thanks for prompting me to check back in with this, it had totally slipped my mind and if anyone i follow has talked about it since the decision was made it's escaped my notice. it's such a shame residents and transients are so much easier to study (and so much better understood as a result) than other ecotypes, i would love to see a really thorough examination of every extant ecotype and a judgment on speciation more broadly. i know they argue for this in the text but of course there's a reason the paper only covered two ecotypes. it feels so weird to see residents and transients listed next to "common killer whale" as if the rest of them are all the same! have you seen what a type D looks like?? i hope we get to learn more about the less studied ecotypes in the not too far future and that future decisions like this can have a broader scope!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I, an uneducated idiot, am going to give my opinion in cetacean captivity, specifically regarding orcas. Specifically specifically regarding SeaWorld.

It's bad that it happened. It's bad that it ever happened in the first place, and when I get to hell I am going to hunt Ted Griffiths for sport for getting the whole thing off the ground.

(more under the cut because this is getting long)

I don't like the commercialisation of SeaWorld. Surely they can study the orcas without making them do tricks for large audiences.

"But Lauren, they stopped doing that!"

Yes, because the public outcry made them stop. They are a for profit company. They did not stop any of this on their own. They did not stop capturing orcas because they felt bad or realized it was wrong. They did not stop breeding orcas because they felt bad or realized it was wrong. I am not anti-zoo, or anti-conservstion. I am strongly anti-capitalist though, and I think SeaWorld as an amusement park needs a whole lot of side eye.

"So Lauren, you think the orcas should go back in the ocean, right?"

Honestly, I don't know. I am just an uneducated idiot, and I wouldn't presume to tell people what to do about it when they might know more than me. Also, historically, I'm going to be honest that it doesn't work well. We did Keiko dirty.

In a perfect world, I would call for wildlife rehabilitation facilities; huge, enormous ones, where all the whales that are family (really, truly family, so mothers would be reunited with their children first and foremost and then we go from there) in captivity could be reunited in sea pools, near enough where wild orcas (of their specific grouping/language) can call to them and they can call back while humans teach them the skills they need to survive in the wild, then release them. This scenario also relies on thriving fish/mammal stocks, which uh. Hmm. An issue for another time, but like I said, this is my idea for a Perfect World. In a perfect world, the other pods would snap up their old and new members easily. We know from Keiko that it is not entirely likely to happen. I also wonder if the captive orcas have their own kind of language borne from different pods being forced together, or at the very least if the younger ones do. The pods of their grandparents might be confused by them, at the very least!

"Lauren, that's not a solution. That's a pipe dream."

Yeah. Kind of. Honestly, it doesn't seem like there's any way to right a lot of these wrongs. It seems that it's a damned if you do, damned if you don't kind of thing; we don't want the whales left in stagnant pools of glass and concrete; if nothing else, they don't have the room they're used to as migratory animals, and they don't have the ecosystem to interact with. We can't release them, they don't know how to be a wild animal anymore. And we aren't kind enough to the natural world to let them figure it out as they go along because they have lost the time they would have otherwise spent learning those skills.

"But Lauren, we know so much more about them now!"

I mean, I guess? Like I said, I am suspicious of the conservation efforts of teaching them tricks for our amusement, and how the captive breeding program that SeaWorld was running seemed to be more for SeaWorld's benefit than for bringing more orcas into our seas. I also don't know how much we can learn if the variable of captivity is there. Does this orca prefer fish because it was from a resident pod, or because they were primarily fed fish by their humans? If they were originally from a transient pod, was the transition to a fish-based diet difficult for them? Would it be difficult to go back? It seems so individual that we cannot possibly know.

BUT I acknowledge your point. Would we have cared to learn as much about them if we didn't have this experience? This capitalist push behind them? I don't think we actually would have. Look at sharks. They have less than 150 marine biologists dedicated to them right now, counting post grad students if I remember that YouTube video essay correctly. We wouldn't know to love orcas if we hadn't done this; hell, they might have been treated like the Great White Shark! It's good that we love orcas and we care about them! It means that we might make better efforts regarding the Chinook Salmon that the Southern Pacific Resident pod thrives on, or reducing pollution, or any number of things. I can't say what knowledge we have lost or gained because of specific actions. Again, it seems so variable that I cannot say. How many marine biologists today were taken to SeaWorld as a child? That seems quantifiable, but how many people didn't go into marine biology as adults because their experience wasn't as good; the weather was bad, their parents fought, the whales weren't performing as well as they did some other day? That the experience was coloured in some way in their perception, pushing them from the field? That's less quantifiable.

So that's my opinion on it. It's not good, and quite honestly it shouldn't have come this far in the first place. But there's really not much we can do about it now, except maybe letting them die with their loved ones.

#cetacean captivity#controversy#orcas#killer whales#discourse#look im really not trying to start anything im just giving my opinion

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kayak Whale Seattle: A Once-in-a-Lifetime Experience

Introduction

Are you ready to embark on an unforgettable adventure in Seattle? Imagine gliding through the gentle waves, surrounded by majestic creatures of the deep. Kayak Whale Seattle is a truly unique experience that will leave you in awe of the natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest. In this article, we will delve into the world of kayaking, the incredible whale sightings in the area, and why Seattle is the ultimate destination for this thrilling activity.

Kayaking: A Close Encounter with Nature

What makes kayaking so special?

Kayaking offers a one-of-a-kind opportunity to connect with the environment in a way that few other activities can. As you paddle through serene waters, you become one with nature, effortlessly blending in with your surroundings. The tranquility of kayaking allows you to fully appreciate the stunning scenery and observe wildlife up close and personal.

Seattle: A Haven for Kayakers

Seattle, known for its stunning natural beauty, is a mecca for outdoor enthusiasts. With its expansive coastline, picturesque islands, and diverse marine life, it sets the perfect stage for a kayaking adventure. Whether you're a seasoned kayaker or a novice, Seattle offers a range of options to suit all skill levels. From serene lakes to challenging ocean excursions, there's something for everyone.

The Whales of Seattle: An Enchanting Encounter

Seattle's waters are teeming with awe-inspiring marine life. However, it's the majestic whales that steal the show. The region is known for its frequent whale sightings, making it a dream destination for nature lovers and wildlife enthusiasts.

The Transient and Resident Orcas

Seattle is home to two distinct populations of orcas: the transient and resident orcas. Transient orcas are known for their nomadic nature, traveling in smaller pods and primarily feeding on marine mammals. On the other hand, resident orcas, also known as the Southern Resident Killer Whales, are known for their complex social structure and primarily feed on fish.

Gray Whales: Mysterious Visitors

Each year, as the gray whales migrate along the West Coast of North America, some of these magnificent creatures make a pit stop in the waters around Seattle. These gentle giants captivate onlookers with their sheer size and grace, often coming close to kayakers, providing a truly enchanting experience.

Humpback Whales: Acrobats of the Sea

Known for their acrobatic behavior and distinct songs, humpback whales are a common sight in the waters off Seattle. Witnessing these majestic creatures breaching and slapping their tails is a sight that will forever be etched in your memory.

Kayaking with Whales: An Unforgettable Experience

What to Expect

Embarking on a kayaking adventure in Seattle provides a unique opportunity to get up close and personal with these magnificent creatures. You may witness graceful breaches, tail slaps, or even hear the haunting songs of humpback whales. However, it's important to remember that these are wild animals, and encounters may vary. Always respect their space and follow guidelines provided by experienced guides.

Safety First

Before venturing out on a kayaking trip, ensure you have the necessary safety gear and knowledge. It's essential to wear a life jacket, prepare for changing weather conditions, and familiarize yourself with basic paddling techniques. Joining a guided tour led by experienced professionals is highly recommended, as they can provide invaluable knowledge and enhance your overall experience.

Conservation and Preservation

As visitors in their natural habitat, it is our responsibility to respect and protect the marine environment and its inhabitants. Keep a safe distance from the whales and other wildlife, and avoid disturbing their natural behavior. By practicing responsible kayaking, we can ensure the preservation of this incredible ecosystem for generations to come.

Conclusion

Kayak Whale Seattle is an experience that will stay with you long after the adventure ends. The breathtaking beauty of the Pacific Northwest combined with the chance to witness these majestic creatures in their natural habitat creates an unparalleled experience. So, why wait? Dive into the world of kayaking and embark on a journey that will leave you in awe of the wonders of nature.

1 note

·

View note

Text

OCs as Animals Tag

Rules: Choose any Oc/s and pick an animal that relates to them and why. You can also include images or drawings of your own but don't have to.

Tagged by @autumnalwalker!

Tagging @vacantgodling @jezifster @late-to-the-fandom @authoralexharvey @korblez @andromedaexists @blind-the-winds @magic-is-something-we-create @tragicbackstoryenjoyer

Here we go:

Isaac: Llama/Alpaca. Smart, quick learner, and can carry more than his fair share of weight through tough terrain. Usually gentle and calm, but when mishandled he'll kick, bite, spit, and refuse to move another inch (just ask Renato). Llamas are braver and more solitary than their alpaca relatives, but will live among other creatures and serve as their guardians. Isaac's curly hair could be compared to the luxurious fleece of an alpaca (again, ask Renato).

Dorian: Pangolin. Rightly described as one of the most endearing creatures on Earth; 110% deserves a global holiday. Also one of the most hunted by unscrupulous people. Curious, great at solving problems, has a good memory, nocturnal, and friendly. Favors defense over offense. No one is immune to the urge to rub their tummy. Never goes anywhere without the protection of a coat.

Renato: Transient Orca. Divided from his own kind not by genes or appearance but hunting habits. Beautiful and deadly as the sea he was born on. An apex predator infamous for playing with his prey before consuming it. But also intelligent, creative, charming, and social, capable of adapting and learning to cooperate with humans and other creatures.

Kinslayer: King Cobra. A devourer of other, lesser serpents, paralyzing them before consuming the victim whole. Swift and powerful, to trifle with Kinslayer is to tempt death. And yet...despite their fearsome reputation they would much prefer to be left in peace, often only striking after extreme provocation or in defense. Cobra venom has also led to breakthroughs in pain medication. On the spiritual side, Sheshnaag, the giant cobra, is said by some to carry the planets on his many heads, and to shade gods as they lounge on his body. To others, cobras symbolize rebirth/reincarnation and creation itself, their coils moving time forward as they stretch, then slowing it to a standstill as they curl up once more.

Elfy: Siamese Cat. Elegant, highly energetic, talkative, playful, loyal and affectionate describes Elfy precisely. (It's true Siamese cats aren't often born deaf despite their blue eyes, but ignore that--it's also definitely part of who she is.) Also loves attention and takes harsh words to heart. Often becomes deeply attached to someone she's decided is her human (see: Isaac).

Ben: Neighborhood Stray Mutt. Part Polish hound maybe, part big shepherd, part who-even-knows-what. A bit uncouth and can be a troublemaker, yet everyone greets him by name when they see him strolling along the streets. Very protective of his territory and his people. Will attack anyone out to harm those viciously. Wary of strangers, but once he gets to know someone, he's affectionate and surprisingly gentle at times. Knows the simple things are best in life: eating, sleeping in a big pile, sex, and the occasional fight (real or friendly--especially if it also leads to sex).

Tilda: Escaped Captive Wolf. Maybe a bit too on the nose, but if it ain't broke, why fix it? Tilda is a (were)wolf with no idea how to wolf properly. Abused and caged from birth, she's only just learning how to handle her instincts, not react with violence due to fear, and be part of the pack. Having Dorian and Ben at her side has gone a long way toward helping. Still hates direct eye contact and probably always will.

Oleander: Honey Badger. Honey Badger dgaf and neither does Ollie. Nocturnal, mostly solitary, tenacious, and has few predators due to her tough hide and ferocious nature. Of course, honey badgers have been known to work with humans and other creatures in the interest of a common goal. Just don't try to screw her out of her share if you want to keep your windpipe intact.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Killer whales seen off Sipadan, reinforces Semporna waters as marine mammal study area

Muguntan Vanar - February 2, 2021

A relatively rare sighting of four killer whales or orcas in waters around Sabah’s famed Pulau Sipadan reinforces the importance of the Semporna region for marine mammals and provides valuable data on marine mammal studies in the area. Footage showing two adult orcas and two calves swimming to the north of Sipadan was captured and posted on social media by Scuba Junkie dive master Arapat Abdurahim last month.

One of the adults was recorded splashing the surface of the water with its tail - ‘lobtailing’ - which according to marine biologists is thought to be a a form of communication between individual orcas, or a warning to stay away.

“It is not unusual for our guests to see marine mammals on their way to Sipadan or on the south side of Kapalai. Quite often, it is dolphins - but on other occasions we are treated to rarer species such as the orcas sighted last week, melon headed whales and even sperm whales.

“It is incredibly exciting for guests and staff to spot a marine mammal on the surface and be able to contribute to the body of research on rarely seen species - for example in 2017, when we reported the first confirmed sighting of dwarf sperm whales in Malaysia, ” Arapat said in a statement on Tuesday (Feb 2).

Scuba Junkie S.E.A.S is a marine conservation organisation based at Scuba Junkie Mabul Beach Resort. The organisation is working with researchers to gather data on the marine mammals that occur in the area and enable more accurate identifications. As incredible as this sighting was - it is not uncommon for the Semporna region which had been identified as a key part of the Western Celebes Sea Drop Off ‘Area Of Interest.

The area has been designated by the IUCN Marine Mammals Protected Areas Task Force due to the high number of marine mammal sightings reported there in the media and on tourism and nature forums. According to a local marine biologist, 21 species of marine mammals have been recorded in the area and most of them were oceanic or deep water species that migrate from the Sulu Sea to Celebes Sea.

“Orcas have been documented in this region before, however, the partnership with Scuba Junkie S.E.A.S has enabled training to be given to local dive operator staff, so we now receive good imagery and clear descriptions from such encounters.

“This has helped enormously in documenting other species with certainty. It is exciting to see this species in the Sipadan area and to have the diving community engage so enthusiastically with our study” said Dr Lindsay Porter from Society of Marine Mammalogy (SMM), which provides funding for the study of whales, dolphins and porpoise in this region. In addition, she said dive operators have assisted this study by also deploying acoustic monitors on the seabed to record marine mammal vocalisations, from which species identification can often be made.

“For many of the marine mammal species seen in the Semporna region, their use of the area is still unknown. It may be seasonal, to fulfil critical aspects of lifecycle patterns, for example shelter for mothers and young calves - such as the orca last week - or transient, as part of a migration route or larger oceanic passages, ” added Dr Porter.

“The use of acoustics as part of this project has allowed us to monitor the area more consistently, meaning that species identification does not solely rely on opportunistic sightings. The acoustic recordings provide us with a detailed soundtrack of marine mammal vocalisations, which will provide us with a more detailed picture of how the mammals use this area, ” she added.

Additionally, Scuba Junkie S.E.A.S conservation manager David McCannsaid they were happy to work in collaboration with researchers and other NGOs to further understand the unique marine environment in Semporna region. He said that this is not the first time an orca with a calf has been spotted in the area.

“Notably, there was an incredible encounter when divers with Scuba Junkie witnessed an orca and calf eating a sunfish in 2019. Examining whether this area has an important role for mothers and calves would be of great interest to many parties, ” he said. Dr Porter, meanwhile, urges caution and care in encounters with the mammals and for people to “behave responsibly around all marine animals, do not get too close to animals or harass or stress them to get footage.”

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Killer whales that feast on seals and hunt in small packs are thriving while their widely beloved siblings are dying out.

illustration of an orca Melanie Lambrick Story by Katharine Gammon

On a warm September afternoon, on San Juan Island off the northwestern coast of Washington State, I boarded J2, a sleek black-and-white whale-watching vessel. The boat was named after a locally famous orca, or killer whale, affectionately known as “Granny.” Until her disappearance in 2016, Granny was the matriarch of J-pod, one of the three resident orca groups, or pods, that live in the surrounding Salish Sea.

For what some experts think was more than a hundred years, Granny returned to these waters every summer, birthing babies and watching them grow. She taught her daughters and sons to hunt Chinook salmon, leading them to where the fish were fat and plentiful. She celebrated births and salmon feasts with other families in her clan, sometimes with as many as five generations side by side. She lived through the decades when humans captured her kin, and through the transformation of the local islands from rocky farms to wealthy urban escapes.

As the boat that bears Granny’s name slowed to cruise under the giant bridges connecting the evergreen-lined shores of the Fidalgo and Whidbey Islands, I heard the loud whoosh of breath exiting a blowhole. Soon, we saw the wet poufs of air erupting from the whales’ shiny black bodies, catching the sunlight. There were six orcas in all, a mother with five offspring ranging in age from one to 13. These whales aren’t members of J-pod or the other two resident orca pods that return to the Salish Sea every summer. They’re transients, showing up in the area only irregularly, and unlike the residents, they eat mostly marine mammals. Their names reflect the distinction: T37A, T37A1, T37A2, T37A3, T37A4, and T37A5. Unlike Granny and her giant group of salmon-eating family members, transient orcas travel in smaller packs and are known for their wily hunting abilities: They can tip a sheet of ice in order to catapult a seal into the sea, or take down a porpoise in midair.

The boat’s captain, Daven Hafey, paused to log the location in an app on his phone; whale-watching boats often record whale locations in order to aid biologists’ research. As we floated, the orca family cruised around a small cove a few hundred yards away. Their breath formed heart shapes as they exhaled.

Soon, they squeezed out of the narrow mouth of the cove and into the open water under the bridge. There, one spy-hopped in the air, poking its monochrome head straight up and looking around.

Suddenly, the whales disappeared, and a uniform ripple appeared on the water’s surface. A small seal was swimming near the rocky shoreline, and the orca family had used its massive collective bulk to send an underwater pressure wave racing toward it. A second ripple rose from the surface, and the seal, knocked off balance, disappeared. Very quickly, it was clear that the family had triumphed: Gulls circled overhead, eager to claim the bits of seal that the whales would leave behind.

This is the hunt, the daily fight of mammal-eating orcas. It’s a dance with these creatures, a constant balance of risk and reward—the more aggressive the prey, the more likely they are to be injured in the battle. While residents have to work together to hunt salmon, salmon don’t fight back. For the transients, Hafey said, every meal is a potential death match: “It’s as if every time you opened the fridge you had to have mortal combat with a turkey to get a sandwich.”

Granny and her kin are considered part of the same species as transient killer whales, Orcinus orca. But residents and transients have lived separate lives for at least a quarter-million years. They generally do their best to avoid each other, and they don’t even speak the same language—the patterns and sounds they use to communicate are completely different. Over time, each type has established cultural traditions that are passed from generation to generation. While transients’ small groups enable them to hunt more quietly and effectively, residents’ large extended families allow them to work together to locate and forage for fish. Biology isn’t destiny, but for orcas, food sources might be.

I grew up visiting these islands, and as I watched the transients hunt and snooze, I felt a sense of familiarity. Like the resident orcas I’d watched for years, the transients were massively intelligent, social creatures, skillfully making a living on a sunny afternoon. But the world these whales inhabit is quickly changing, and the old rules no longer apply. As the summer residents travel farther and farther, searching for the salmon they need, these once-scarce transients are rising to rule the Salish Sea.

In the summer of 2018, a resident orca named Tahlequah had a calf that was stillborn, or lived for a few minutes at most. Tahlequah carried her calf’s body through the water for more than two weeks, sometimes holding it in her mouth, sometimes nudging it along with her nose. She kept the small carcass afloat for some 1,000 miles, even as it began to disintegrate into strips of flesh.

Tahlequah’s story went viral, perhaps because her grief and desperation seemed so human. Kelley Balcomb-Bartok, who took a famous photograph of Tahlequah carrying her dead calf, told me the image spoke for itself: “That needed no messaging. It was a gut punch.”

Since the 1990s, the resident orcas have been the superstars of these islands—the most photographed, most studied, best-loved group of whales in the world. They have been featured in a movie (Free Willy); they have a museum dedicated to them; they have individual names and backstories; and they have fans who paint buses in their honor.

For many people, the relationship with the whales verges on the spiritual. “It’s hard to describe—it’s like meeting God,” said Balcomb-Bartok, who grew up on the islands and works in communications for whale-watching companies while compiling memoirs and sketches related to the orcas. “They’re so amazing and intelligent and powerful, and yet they are so gentle and so matriarchal and caring and compassionate. There is nothing quite like … the southern residents—the most playful and loving population that you’ll ever meet.”

But these island celebrities are slowly dying. Forty percent of the Chinook salmon runs that enter the Salish Sea are already extinct, and a large proportion of the rest are threatened or endangered. The fish that are still around are much smaller than their predecessors, forcing whales to work harder and swim more for their meals. The resident population now numbers only 74, down from 97 in 1996.

Meanwhile, the sea lion population on the West Coast, which was protected from hunting in the United States and Canada in the 1970s, has bounced back from near extinction and is close to its historic size. The mammal-eating transient orcas are thriving in part because of this boom: During the years that Tahlequah was believed to suffer a miscarriage and the death of her newborn calf, T37A birthed the five calves who now played by her side. The transient population, which in 2018 reached 349, grew at about 4 percent a year for most of the past decade, and is well on its way to replacing the residents as the dominant killer whale in the Salish Sea.

But many of the humans who love the orcas of the Salish Sea are ambivalent about the transients’ success. While the residents are well-known individuals, the transients are relative strangers. Even when they’re in the area, they’re harder to get to know, because their need for stealth means they surface less often. “There are people on whale-watching boats who are disappointed when they see transients and not residents,” Monika Wieland Shields, a biologist who runs the Orca Behavior Institute on San Juan Island, told me. “You’d think the general public would be interested—but there is this tangible phenomenon where they are disappointed by the transients.”

“We’re certainly getting to know the Ts,” says Mark Malleson, a Canadian whale-watching captain who has been contracting for Fisheries and Oceans Canada and collaborating with the Center for Whale Research as a research assistant since 2003. “Because they’re the new residents. The whale-watching industry was built on southern residents, and we just don’t see them much anymore.”

In the 1960s, unfounded rumors of killer whales’ ferocity and appetite for human flesh gained traction; fishers came to believe that orcas competed with them for salmon. Then, in 1964, the public got its first close look at the species. When the Vancouver Aquarium tried to capture and kill an orca for its specimen collection, it wounded a young orca instead, and the whale, dubbed “Moby Doll,” lived for a few months in Vancouver Harbor before dying from an infection. During its time in the bay, Moby Doll demonstrated just how intelligent and social orcas could be, and for some observers, a capitalistic light bulb went on: Orcas were good entertainment, and entertainment could make money.

Thus began the capture era, in which about 30 percent of the Salish Sea’s orcas—mostly residents, as they were more plentiful at the time—were swept up into captivity. In one particularly gruesome event near Whidbey Island, a floating pen was set up to separate orca mothers from their babies, as their piercing screams filled the air. “It was a sight and sound that would haunt the local residents forever,” Sandra Pollard, who wrote a book on the capture, said on the 50th anniversary of the event in August of last year. Pollard recounted one longtime resident whose children asked why the whales were crying.

By 1973, 48 whales had been captured and sold to aquariums around the world, and an additional 12 had died during the capture operations. In 1970, a young Canadian marine biologist named Michael Bigg was asked by the Canadian government to figure out how these captures were impacting killer whale populations. The next year, he created a census of whales that relied on sightings and soon after began to use photo identification to pinpoint individuals. Not everyone agreed with his methodology, but Bigg persisted. Armed with a budget from the Canadian government and considerable force of personality, he got to work—once even chartering a seaplane, landing near the whales, and persuading a fishing-boat captain to take him close enough to identify the animals. If he could photograph every whale in enough detail, he believed, he could begin to study them as individuals.

Bigg soon began mentoring a new generation of whale scientists, including Ken Balcomb, who now runs the Center for Whale Research in Friday Harbor, and John Ford, who was a graduate student under Bigg’s tutelage. Ford started a rigorous study of whale language, dropping hydrophones 40 feet into the water to document the dialects of different whale groups. He speculated that residents might tend to choose mates whose “accents” were different enough to signal a low risk of inbreeding. One of Ford’s students later did a genetic analysis that bore out this theory.

These researchers had also started to encounter scrappy little groups of whales living apart from the familiar large pods. There were fewer of them, and they had erratic, unpredictable movements. Bigg and his colleague Graeme Ellis called them “oddballs”—outcasts who didn’t fit in. They turned up in places the large pods didn’t go, and they would dive for long periods, twice as long as the other whales.

“It wasn’t clear what they were,” Ford, now retired as the head of the cetacean research program at Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s Pacific Biological Station, told me. “Mike felt they were possibly social outcasts from large groups, which is typical in social mammals, and that they were scratching out a living with low-profile behavior.” It was Bigg who started calling these scrappy outcasts “transients”—he thought they were in transit, moving like lone wolves through a pack’s territory. They had a pointier fin shape, and their gray saddle patches were large and often more scratched up than those of the residents. On a couple of occasions they were seen killing seals, though at the time it was thought that the residents ate seals, too.

When Ford started matching his hydrophone recordings with the photo surveys and eating profiles, he began to wonder if the transients were fundamentally different creatures. They were often quiet as they hunted, but when they shared prey they would break into a loud chattering, markedly different from the residents’ squeaks, whistles, and whines. After long days on the water, Bigg and Ford, along with other researchers, shared their thoughts and observations over the occasional beer, and gradually they concluded that the transients weren’t social outcasts but a distinct population with a different lifestyle.

In the late 1970s, the orca survey in Canada started to focus on the northern residents and transients, while Americans took up the work on the southern residents. Balcomb moved up to San Juan Island and began doing the survey with his team, which still counts and monitors the southern residents every year. Eventually, others began to take an interest in the summer residents beneath the waves: In 1986, a local car salesman got his captain’s license and started ferrying tourists out to see the resident orcas. Today, more than half a million people go whale watching around the islands every year.

Bigg was diagnosed with leukemia in the 1980s, but he continued to research and write until his final days. His ashes were spread in Johnstone Strait, British Columbia, where the whales are often seen. More than 30 orcas were present during the ceremony. “One whale in the group, G29, was seen with a new calf,” Ford said. Bigg had predicted that G29 would give birth to her first calf that year, so calf G46 was nicknamed “MB.” In Bigg’s honor, many scientists in recent years have begun to refer to transient whales as “Bigg’s killer whales.”

In 2005, when the southern resident orcas were listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, the population’s distinctive language, behavior, and habits were recognized as a unique culture. It was an unusual moment for the law to acknowledge that cultural diversity wasn’t limited to humans, and that it was worthy of protection in other species, too.

Last year on July 4th, the summer heat was finally beginning to warm the islands in earnest. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, none of the usual games or parades were going forward. And while the resident orcas had turned up on schedule, they weren’t acting like themselves.

There was no “superpod”—the giant annual party of all three southern resident groups—and the orcas weren’t lining up as they usually did to search for fish. “We are seeing much less in the way of traditional foraging, and a lot more traveling,” Monika Wieland Shields, the Orca Behavior Institute biologist, told me in July. “They are not staying here for long periods of time. They’ll come in, do one lap of their traditional circuit, and then move on. It’s almost like checking the fridge, checking the cupboard, and then they have got to go somewhere else to eat.”

Howard Garrett, who runs the Orca Network, a nonprofit organization that documents sightings of the whales, told me something similar: “They were scattered in 1-2-3s, very sporadic, no travel essentially, and no socializing except the mother-offspring group,” he said, behavior that could only be interpreted as the whales “searching every nook and cranny for a fish, each one of them looking for a crumb.”

The residents’ diet is more than 80 percent Chinook salmon, fish that just aren’t around much anymore. The Albion test fishery, which uses a gill net every day during the spring and summer to count fish coming from the Fraser River in British Columbia, caught a total of only 14 Chinook salmon from July 1 to July 12 last year. (In the same period of time in 1992, the fishery counted 384 Chinook salmon.) Without a reliable supply of fish, the resident orcas are beginning to behave more like transients. But, unlike the transients, they can’t just start eating squid, herring, or seals—they learn from birth that fish is their only food.

“They can’t change their diet,” Deborah Giles, an orca researcher with the University of Washington Center for Conservation Biology, told me. “Theoretically, they could, but I’m reluctant to say they will switch, because they have this deep, intense cultural direction from their moms not to eat that thing.” (By occupying different positions on the food chain, the residents and transients avoid competing with each other, lessening the likelihood of aggressive encounters.)

The transient orcas are changing their behavior as well, Shields told me. While they typically travel and hunt as small family units of three to five whales, she’s recently seen them traveling in groups of 20 to 40. The groups are almost like the resident superpods of years past, Shields said. Researchers have nicknamed them “T-parties.” “They’re definitely less focused on being stealthy and hunting,” Shields continued. It’s possible that mammal-eating orcas have such abundant food that they don’t need to spend as much time hunting—and can spend more time socializing.

While many tourists are entranced by the star power of the southern residents, others ask why we care so much about one type of orca when another is ready to take its place. “There are no other whales that are like them,” Giles said of the residents. “They are a unique tribe of beings that have been here for thousands of years in this region, foraging on abundant and fatty salmon. Because everything that is plaguing them is caused by humans, I feel that we have a deep responsibility to do everything we can to recover them. To preserve that uniqueness.”

In early September, the whale paparazzi were buzzing about a celebrity birth. Tahlequah, after losing her calf in 2018, had finally given birth to a healthy baby, and both whales and humans seemed to breathe a sigh of relief. A few days after the birth, the entire southern resident population formed in a superpod for the first time all year. Tahlequah and her new baby swam alongside the group; from nearby boats, tourists and researchers watched in awe.

Read: why killer whales (and humans) go through menopause

I called Darren Croft, a U.K.-based researcher with the Center for Whale Research, for a read on the event. He was both excited for the new calf and sad that he wasn’t in the Salish Sea to see it. “Also, one calf is not going to fix this population,” he said. “It’s certainly not a green light.”

Croft and his colleagues have shown that in the southern resident population, long-lived, post-reproductive females are important for the survival of offspring and grand-offspring. This “grandmother effect” is thought to be another distinctive feature of the population’s culture; only a handful of mammal societies are known to have female leaders—elephants are another example—and even fewer have leaders who have lived past their species�� equivalent of menopause.

Croft and others are beginning to learn more about transient orcas’ culture, trying to construct a map of the whales’ social networks. Part of the challenge is that while charting the residents’ lives—their births and deaths and movements—has been part of scientists’ work since the 1970s, the transients haven’t been studied to the same level.

While the residents’ sons and daughters stay with their moms for life, Croft said, both sexes of transient calves can disperse by the time they’re teenagers—presumably so the groups don’t get too big to hunt efficiently or to all share in the kill—or they may stay with their family group. There are still many open questions about the transients’ longevity and life history. Some recent observations are opening up new lines of research: A paper published this month describes how transients in the Salish Sea can intentionally strand themselves, hauling their bodies out on land, in order to hunt seals.

Many of the experts I spoke with fondly remembered the resident orcas splashing and playing before their precipitous decline. But some researchers are becoming fans of transient whales as well. The transients sharply increased their visits to the Salish Sea in 2017, and Shields told me it’s exciting to see those babies grow up. “We are getting to know them as they spend more time here,” she said. “It’s a learning curve: What is their history, and how can we help people connect to them?” But when I asked Shields and other researchers to name their favorite whale, not one named a transient.

One transient that has gained some individual notoriety is an all-gray whale who is a member of the T46B family. He is nicknamed “Tl’uk,” a word that means “moon” in the language of the Coast Salish Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest. His color makes him appear white in the dark green of the water, and pictures of him have spread around the world. But his fame comes more from his appearance than his actions. As with so many transients, his life story has yet to be uncovered.

“It’s just very different,” Howard Garrett, of the Orca Network, said. “It’s sort of—instead of Cirque du Soleil, you get the traveling trapeze artist.” He quickly added that the transients are fascinating in many other ways. But, he said, “they don’t have that community-celebration feel when they’re around.”

Kelley Balcomb-Bartok, the naturalist who took the photo of Tahlequah and her dead calf, told me the notion of “good whales” and “bad whales” is ridiculous. So many of the qualities that people love in the residents are equally present in the mammal-eating orcas, he said: “The Bigg’s whales are playful: Once they hunt, they play. And they are family oriented. Their mothers still birth and carry them; they do it in just small matrilineal groups. They will mix and match. They will separate. If you go on one of those whale-watch boats, you’ll hear the naturalists talking about [Bigg’s whales] the same way we used to talk about the southern residents.”

The transients also face threats—boat traffic, toxicants in the waters—but nothing like the starvation that many experts see in the residents’ future. Humans have built dams and poured concrete into the estuary waters that salmon need to survive, but we have deliberately protected the seals and other pinnipeds that supply mammal eaters with an endless seafood buffet. We have created the conditions that caused Tahlequah to lose her babies but enabled T37A to birth five calves in 13 years.

In the Friday Harbor whale museum on San Juan Island, a small sign contrasts the feeding habits of transients and residents. The mammal eaters are said to be “attacking” their prey, while the fish eaters are merely “eating.” But no matter their culture, their goals are the same: to fill their bellies and have more babies. The whales don’t know that humans see one act of eating as more violent than the other.

The residents are speaking, loudly, to anyone who is listening. They are moving away from their summer homes, searching high and low for salmon they once found with ease. They are struggling to give birth, to keep their babies alive, to keep up with a rapidly shifting world. At the same time, the transients are quietly waiting to be heard.

Katharine Gammon

is a freelance science writer based in Santa Monica, California. This article is part of our Life Up Close project, which is supported by the HHMI Department of Science Education.

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2021/01/orcas-killer-whale-resident-transient/617862/?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Read: What the grieving orca tells us

Read: The lingering curse that’s killing killer whales

A Group of Orca Outcasts Is Now Dominating an Entire Sea

Killer whales that feast on seals and hunt in small packs are thriving while their widely beloved siblings are dying out. Katharine Gammon

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

As you can likely tell from this video, we had a very hard time leaving Orcas Island in Puget Sound. This area, including the Olympic Peninsula is just truly stunning. Enough about the area, let’s talk about ORCAS! We had to basically go as far as this tour boat has gone, in the Juan de Fuca Strait, to get some whale action - and the sea sickness was totally worth it!!! You can hear our Naturalist guide in the background enthusiastically shouting,” THIS NEVER HAPPENS!!!” over and over again. 😂 Essentially, we came upon two transient Orca pods that were following lunch, the Harbor Seals. 🦭 And we speculate that after everyone in the pod got a tasty bite, they each celebrated by breaching! What are the chances they would do that right in front of OUR boat and that we were at this exact spot to witness this wildly amazing event!?!?!? Like, Whaley!?! 😉There were at least five breaches, three of which was captured!!! Soon after, the pods separated and went their own way. #godscreatures

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rake Marks on Wild Orcas

Rake marks on wild orcas is a hot topic in the debate over orca captivity, and people on opposing sides frequently butt heads over this issue. Unfortunately, there is a moderate amount of misinformation that occurs in both pro-cap arguments and anti-cap arguments. I have gathered some information about rake marks and aggression in wild orcas that I hope we can all use when constructing arguments.

I am anti-cap, obviously, but this post is not meant to be for or against captivity; I’m really not interested in trying to manipulate info to fit a narrative. I just want to lay out some facts on wild orcas and rakes. All of this information is taken from scientific papers, statements from wild whale researchers, and other reputable sources.

What is a rake mark?

A rake mark is essentially the result of an orca dragging its teeth across the skin of another. They’re thin, evenly spaced parallel scratches, usually in rows of 3-4. Orcas have rake marks throughout their lives. Sometimes rakes turn into scars, sometimes they don’t. Some rakes can be shallow and short in length:

[X]

Or they can be longer and a little deeper:

[X]

On rarer occasions, wild orcas can have prolific scarring caused by rakes:

This individual, among others, was studied in Ingrid Visser’s paper on scarring and dorsal collapse in New Zealand orca. She concluded that, “the prolific body scars on the two adult male killer whales appear to be unusual and are the first of their type reported in the literature. They are almost certainly caused by conspecifics.” This amount of raking in the wild is very, very unusual; it’s why Dr. Visser wrote part of that paper about it!

It is important to note that not all scratches and nicks on an orca’s body are caused by conspecifics (other orcas). For example, some orcas in Iceland have skin markings caused by parasitic sea lampreys! However, marks caused by orca teeth are very distinctive and it’s hard to mistake them for something else; in fact, they’re so distinctive, researchers know when orcas have attacked baleen whales because they leave similar markings on the whales’ bodies. This can be seen in humpbacks and bowheads.

Which Whales Have Rakes?

All ecotypes and populations of orcas have some degree of rake marks. They have been observed in orcas all around the world. These are pretty common markings on wild orcas, and you can observe them in the ID catalogs of many, many populations. Residents and transients are some of the most studied orcas in the world, so we have good information on them in regards to rake marks: “Resident and transient whales typically showed extensive rake marks on their dorsal fins and body made by the conical-shaped teeth of conspecifics (Ford et al. 1992, Black et al. 1997, Dahlheim et al. 1997).” The rakes on offshore orcas, while not as extensive as in other populations, can look a little different because that ecotype tends to have blunt, worn teeth: “During our analyses of photographic data on offshore killer whales, we did not observe extensive rake markings. We did, however, see wider and shallower markings on the skin of offshore killer whales, the width of which was consistent with rake marks inflicted by teeth that had extensive wear.”

Why Do Orcas Rake Each Other?

This is where it gets tricky and harder to answer. Orcas, unlike some other animals, tend to get along pretty well with one another. They are not territorial, and they have mechanisms that allow them to live in the same area with other populations of orcas without competing for the same resources (e.g. food). So why the heck do they have rake marks? Well, sometimes we don’t always know, but we have some ideas!

Though orcas are overall peaceful, they do have spats and can behave aggressively towards each other sometimes, but this does not happen often. It has been said that mother orcas will sometimes discipline/corral their calves by raking them. Researchers also think that rake marks can be received during rough play. Orcas can also receive rake marks from, believe it or not, being helped by another orca. There have been cases of orcas carrying and assisting ill calves and inadvertently causing extensive scarring on their bodies. More recently, it was revealed that orcas may act as “midwives,” if you will, and assist other female orcas in birth. Researchers believe that these rakes on young J50 were inflicted when another orca pulled her out of the womb of her mother with their teeth:

[X]

Another calf, J54 Dipper was seen with his sister, J46 Star, and cousin, J47 Notch, who carefully held him between their bodies to assist him. Once he started to sink, Star desperately grabbed her baby brother in her mouth to bring him to the surface causing severe rake marks on his dorsal fin. Unfortunately, despite Star and Notch’s best efforts, Dipper did not survive and died of starvation.

[X] Unfortunately, it’s hard for us to watch the behavior of wild orcas all of the time, so it’s usually nearly impossible for us to look at a particular set of rake marks on a whale and determine if it came from an aggressive interaction or from a more mellow interaction. But here’s what we know for sure:

What’s normal: small amounts of rakes, such as those seen in the first photo in this post.

What’s not normal: extremely extensive/prolific rakes, such as those seen in the third and last photos in this post.

I hope this cleared up any confusion/questions you may have had about rake marks in wild orca. If I have mistakenly included any wrong information, please let me know and direct me to other sources!

#orcas#southern resident orcas#southern resident killer whales#J50 Scarlet#J54 Dipper#Rake Marks#Wild Orcas#Captive Orcas

18 notes

·

View notes

Link

The endangered southern resident killer whales which are normally spotted in the Salish Sea near Vancouver throughout June, haven't been seen by researchers or whale watchers in the area and the absence is considered highly unusual for this time of year.

"We believe that is because there currently aren't enough chinook salmon returning to the river area. So they have to be somewhere else to get food," said Joan Lopez, a marine naturalist with Vancouver Whale Watch, a tourism outfit.

On one of the final days in June, tourists with binoculars and cameras watched as a group of 14 transient killer whales swam off the coast of Vancouver. These orcas are a different type of killer whale and eat seals — unlike the southern residents, whose diet only consists of fish.

The southern residents' range extends from southeast Alaska to central California, but during the summer months they feed and live in the Salish Sea.

While seals are plentiful in the coastal waters of B.C. and Washington, chinook salmon — the southern residents' main prey during the months of May to August — are not.

"These whales are not getting enough to eat at any time in the year," said Deborah Giles, the director of science and research at Wild Orca, a U.S. based non-profit.

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

Its literally so surprising to me that there haven't been MORE humans killed by captive orcas bc so many who were captured were transients and so many more who were bred have transient DNA. Transients eat mammals like dolphins and seals. They're only fed dead fish in captivity which means they're not eating what their instincts tell them to AND they're not hunting. And then people decided it would be a GREAT idea to dress humans (mammals 🤓☝️) up in black wet suits and put them in the water with them. Are we trying to see how much like a seal you can make a person look???? I mean orcas are smart and can tell the difference but you're basically waving steak in front of a dog while only ever feeding it kibble. You're pissing them off. I personally think they should get to kill more often. Not trainers necessarily. Put the SeaWorld CEO in the water with them and let them go crazy (but fr it shows how patient and kind they are and how far the ones who have attacked had been pushed to get to that point)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Turns out there's another ocean creature that scares the hell out of great white sharks

https://sciencespies.com/nature/turns-out-theres-another-ocean-creature-that-scares-the-hell-out-of-great-white-sharks/

Turns out there's another ocean creature that scares the hell out of great white sharks

Just when you think orcas couldn’t possible be any more awesome, they get even better. A study in 2019 showed these whales are really good at scaring off the most feared beast in the sea. Yep. Orcas have toppled the great white shark off their ‘apex predator’ throne.

A team of marine scientists found that great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) will make themselves extremely scarce whenever they detect the presence of orcas (Orcinus orca).

“When confronted by orcas, white sharks will immediately vacate their preferred hunting ground and will not return for up to a year, even though the orcas are only passing through,” said marine ecologist Salvador Jorgensen of Monterey Bay Aquarium.

The team collected data from two sources: the comings and goings of 165 great white sharks GPS tagged between 2006 and 2013; and 27 years of population data of orcas, sharks and seals collected by Point Blue Conservation Science at Southeast Farallon Island off the coast of San Francisco.

The team also documented four encounters between great white sharks and orcas in the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, which they could then analyse against the other data.

The data revealed that whenever orcas showed up in the region – as in, every single time – the sharks made a swift exit, stage left, and stayed away until the next season. They would choof off within minutes, even when the orcas only hung around for less than an hour.

And there was a surprising beneficiary: the elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostrous) that inhabit the coastline and are preyed upon by the great white sharks.

“On average we document around 40 elephant seal predation events by white sharks at Southeast Farallon Island each season,” said marine biologist Scot Anderson of the Monterey Bay Aquarium. “After orcas show up, we don’t see a single shark and there are no more kills.”

Transient orcas have also been known to eat the elephant seals, but these visiting whales only show up infrequently. Resident killer whales feed on fish.

The sharks didn’t always go far. Sometimes they would only move a safe distance along the coast, where they were close to different elephant seal colonies. Sometimes, though, they would head out to the middle of the Pacific Ocean, the region dubbed the White Shark Café.

These are not tiny sharks, either. Some of them measure over 5.5 metres (18 feet) from nose to tail, and are probably pretty used to getting their own way wherever they go. But 5.5 metres is on the small side for orcas, which can prey on whales much larger than that, so they’re unlikely to be pushed around easily.

In addition, orcas have been observed preying on great white sharks around the world, including near the Farallon Islands. It’s still a little unclear why, but the orca-killed sharks that wash ashore (one is pictured at the top of the page) are missing their livers – their delicious, oil-rich, full-of-vitamins livers.

Whether the sharks are instinctively avoiding the predators that can so handily eviscerate them, however, or whether transients in the past have bullied the sharks away from the elephant seal food source is still an unknown.

“I think this demonstrates how food chains are not always linear,” Jorgensen said.

“So-called lateral interactions between top predators are fairly well known on land but are much harder to document in the ocean. And because this one happens so infrequently, it may take us a while longer to fully understand the dynamics.”

The research was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

A version of this article was first published in April 2019.

#Nature

1 note

·

View note

Note

Do 🐋whales ever swim by your island?

yes! we have many resident & transient orcas, as well as humpbacks, pacific grey whales, and i think a few other less common ones. we also get lots of dolphins & porpoises!

here’s a few orcas i saw on the ferry to vancouver earlier this year:

8 notes

·

View notes