#visual design is inherently cryptic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Recently Viewed: Angel’s Egg

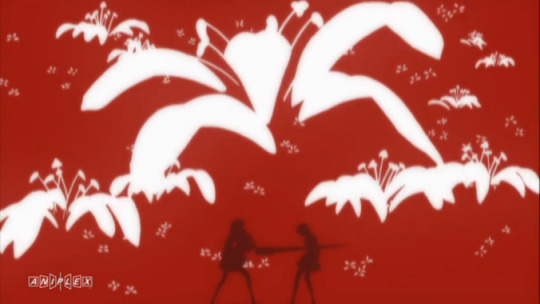

In the 1980s and 1990s, a lot of anime was produced exclusively for the booming home video market. Freed from the more stringent censorship guidelines associated with traditional distribution models (theatrical, television), these relatively low-budget “OVAs” became synonymous with “Mature Content,” a misleading label that in this context alludes to extreme violence and sexually explicit material (see: Demon City Shinjuku, Wicked City, Doomed Megalopolis)—superficial pleasures that are not totally without merit, but are nevertheless rather juvenile. Angel’s Egg, however, is genuinely mature; this hidden gem—which has only recently been rediscovered and critically reevaluated after being largely dismissed upon its initial release—is thematically rich, emotionally resonant, and exquisitely crafted. I don’t know if I even possess the language required to articulate what makes it so utterly compelling… but that will hardly discourage me from trying anyway.

The film begins with a tight closeup on a pair of small, delicate hands. Gradually, the thin wrists rotate, allowing the viewer to observe the creases in the pale flesh, the lines on the palms, the faint sheen on the nails; the joints audibly crack and pop as the fingers flex, curling into clenched fists. This minute attention to detail permeates every subsequent frame. Individual strands of hair billow gracefully in the breeze, mirroring the swaying motion of rustling grass. The reflections of gnarled tree branches ripple on the deceptively placid surface of a subterranean lake. Later, this same body of water slowly envelops our heroine’s calm, tranquil features as she sinks into its dark, icy depths.

Although director Mamoru Oshii (Ghost in the Shell) provides fluid movement and a hypnotic rhythm, Yoshitaka Amano (whose cinematic credits include Belladonna of Sadness, but who is probably better known in the United States for his Final Fantasy concept illustrations) contributes the vital framework, sculpting the visual style and establishing the oppressively bleak, haunting tone. His character designs, of course, are instantly iconic. The protagonist is particularly striking; her skin is so immaculately white that it almost appears to radiate light, starkly contrasting the dull, drab, monochromatic gray shade of the setting—a nightmarish realm of carved stone, shattered glass, and petrified bone wherein the inhabitants resemble the surrounding gargoyles and solid objects are indistinguishable from their own shadows. The backgrounds are equally evocative: barren, desolate wastelands stretch out for miles beneath the blood red sky, while the architecture is a surreal, chaotic amalgamation of Gothic cathedrals, industrial factories, and techno-organic horrors beyond human comprehension.

As for the plot… well, to be perfectly honest, it’s far too minimalistic to be properly summarized. Indeed, attempting to describe the story in literalist terms is inherently futile; the narrative is entirely figurative, revolving around such recurring motifs as feathers, fish, machinery, moisture, and incubation. Naturally, I have my personal theories regarding the intended “meaning” behind these cryptic symbols (they could represent the conflict between religion/spirituality and rationality/skepticism, for example), but I would prefer to avoid delving into concrete interpretation; to dissect the movie from an academic, intellectual perspective would merely diminish the captivating beauty of its ambiguous subtext.

Ultimately, Angel’s Egg is unlike anything that I’ve previously encountered. Sure, it’s possible to identify a few obvious artistic influences (H.R. Giger, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Andrei Tarkovsky), but such shallow Easter egg hunts are fundamentally reductive when applied to films as singularly unique as this. In an industry defined by repetitive formulas and generic archetypes, Oshii and Amano created a defiantly unconventional, experimental, avant-garde masterpiece. I’m glad that I was able to experience it on the big screen, alongside an enthusiastic audience—thank you, Japan Society!

#Angel's Egg#Yoshitaka Amano#Mamoru Oshii#Japan Society#Japanese cinema#Japanese film#Japanese animation#anime#animation#film#writing#movie review

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comics Review: ‘Batgirls’ #1

Batgirls Vol. 1 by Becky Cloonan My rating: 3 of 5 stars Gotham is on fire. Again. (Still?) And fortunately or unfortunately, by this juncture, fewer and fewer people truly care whether anyone is around to douse the flames. Which could be a good thing for Team Batgirl, whose combined ranks of Gordon, Cain, and Brown might slip among the shadows a little bit easier. But nothing really goes as one hopes when crimefighting in a city on fire. In BATGIRLS v1, readers breeze into the chaos midstream: Team Batgirl fights off a street artist with a knack for mind control, encounters a trio of well-equipped militant extremists, defends against a prodigy hacker, and as often happens when dealing with teenage superheroes, the team, from time to time, must also combat its own stupidity. BATGIRLS v1 successfully executes what many recent iterations of Batgirl have done: blend new stories of familiar heroics for new readers. Barbara Gordon is the big sister with a mind for strategy and gadgetry. Cassandra Cain is a strong, silent, and efficient partner looking for comfort among close friends. And Stephanie Brown, who is especially chatty, hates villainy with a casual efficiency that would be terrifying if she weren't so exceedingly upbeat. Few comics fans who thrive on more parochial ("classic") narrative tales of any of these characters will fall in love with this new comic. But that's okay. For what BATGIRLS v1 hopes to achieve, the character relationships and plotting mostly hit the target. The book struggles to balance its quest to entertain as well as the necessity of narrative focus. Does the team settle on relocating its hideout after a bomb threat, does it pound the pavement in search of an upstart mind-control freak, does it crack down on a hyped-up group of well-armed militants, or does it track down a hacker who has infiltrated Oracle's network? Lots of entertaining stuff. But ultimately very poor focus. Some of these stories are relegated to C-level priority, despite being introduced as a big deal. For others, the reverse feels truer than not. For example, The Saints, sharp assassins bearing some sweet gear, enter the story early only to falter and feather into the background. Team Batgirl gets its butt kicked the first time around, but in the end, the headhunters are a piece of cake. Is this another casualty of Big Two comics promising more than it can deliver? Regardless, it's kind of a letdown. BATGIRLS v1 leans heavily on the antics and dynamics of its co-protagonists. Cass is generally mum, but she doesn't hesitate to voice her opinion when her emotions rise to the fore. Steph is written precisely like a modern teenager, which is to say, she somehow balances being incredibly productive while also being dreadfully annoying. The two girls would make for the center-point of a killer series, when they're older, about Batgirl Roommates. But for now, side stories and commentary involving oddball pajamas, burned pancakes, and pierced ears will have to do. Visually, the comic employs an effective art style that works well with these iterations of Cain and Gordon but doesn't always mesh with Brown's ebullience. The book's sharp, angular, fed-from-the-shadows visual design is inherently cryptic, and more than suitable to the storytelling atmospherics of a city lulled to sleep while still on fire. The art in this book really stands out, from the geometric silhouette of Cain's cape to the incredible color-mix of psychosis and psychedelia readers engage, once fear gas is introduced into the story. Perhaps if the book reduced its villain count and narrowed its narrative trajectory, then the art team's work would've been even more effective. BATGIRLS v1 thrives, but ebbs and flows considerably in the process. The character voices are distinct and the art delivers on all accounts. But the story problematically overloads when it should instead pick and choose its challenges.

Comics Reviews || ahb writes on Good Reads

#comics reviews#batgirls#review#becky cloonan#michael w conrad#sarah stern#ivan plascencia#cassandra cain#stephanie brown#barbara gordon#jorge corona#becca carey#batfamily#superheroes#dc comics#3 of 5 stars#goodreads#burned pancakes#militant extremists#necessity of narrative focus#dreadfully annoying#visual design is inherently cryptic#relocating its hideout#psychosis and psychedelia#a city on fire#batman

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being Hopeful [a *personal* Komahina writeup]

*major Danganronpa 2/2.5/3 spoilers ahead*

Someone told me to gather my thoughts into a post so here it is.

Note: Unless you’re up for a challenge to potentially reshape your opinions towards certain ships, if you think Komahina is by default a toxic ship in anyway shape or form, or if you firmly believe that Hinanami is “bestest Hinata ship OTP owo”, it’s not in your best interest to read this post. I’m not suggesting you are invalid or wrong, but you’re likely not the group of people I’m looking forward to having a constructive and evoking conversation with.

First off, I might have been recognized as an avid Komahina shipper, and my opinions towards Hinanami could be generally summarized as ambivalent/mixed/minorly favourable. I was able to acknowledge Hina/Nami’s relationship as of roughly equivalent significance in regard to DR2’s theme.

But it was impossible for me to consider the two relationships narratively equal, I was able to notice that Koma/Hina was a “meant to be” endgame relationship right of the bat, yet Hina/Nami reads as this transitory experience of an obscure puppy love, or “yeah that happened” that’s melancholic and beautiful. Evidently, the narrative strongly favoured Koma/Hina in terms of screentime, development, complexity, compatibility, and endgame potentials.

I wasn’t too confident about why Komahina screams an ultimate destination of a Hinata relationship to me, yet Hina/Nami never convey a remotely similar message. In many aspects, I didn’t ship Komahina in the past for the sake of “I want Komaeda to savour happiness” but placed more emphasis on “it would be wise for Hinata if he could ascertain that his future is with Komaeda”. However I couldn’t elucidate why I thought so.

But due to some unexpected changes in my personal life, it was so effortless for me to reach an epiphany why Hinanami couldn’t quite be the same Hinata-OTP as Komahina. And now I’m kicking myself for not being able to be more adamant about it earlier.

In short, I had a brief taste of how “true bond” or “true connection” functions. It was an estranged, uncharted experience to me prior to that “sudden change”. And in retrospect it’s unimaginable how I survived that bitter life of pure bleakness without it. But since I was able to discern the characteristics of a “true bond”, Koma/Hina, while being excruciatingly complicated and bitter in canon timeline, had a great foundation for that nonetheless, while Hina/Nami was, fundamentally “deficient” in this specific department.

Hina/Nami, either the DR2 or DR3 iteration, doesn’t go beyond being a fine relationship. It’s not bad, as adolescent crushes are typically not bad. It’s functional and somewhat sweet if Hinata was just some normal shy boy who at some point met a nice caring pretty girl. But a great, monumental relationship doesn’t come from being just fine, and Hinata is much more messy than a such-and-such average joe as what a part of the fandom preferred to project him as.

But Hinata wasn’t an adequate rival and foil for Komaeda, that ridiculously multilayered character likely in all fictions for nothing.

For starter, Hinata committed Izuru Kamakura and countless war crimes, for fuck’s sake.

I had this pessimistic outlook that humans aren’t truly designated at birth to understand each other unless they are. Real life Nanami being the talented, worthy Ultimate Gamer she was, even if she could acknowledge and validate Hinata’s struggles as a talentless person, and brought him some temporary comfort and solace, she could not understand the full spectrum of complications the struggle itself entails. Being the kind and somewhat compassionate person she was, she’d try to understand Hinata if he ever decided to open up, but she’d likely just go “yeah talent doesn’t really matter you should just be confident in yourself” as long as she’s not some Ultimate Empath like Makoto (or Junko) all at the same time. To her, Hinata’s decision to Izuru-fy is unfavorable, but not particularly tangible.

It’s somewhat similar to a moderately affluent person not knowing what an impoverished/economically-challenged life entails, they could never understand why it’s necessary for anyone to opt for crimes and prostitution and shit, if you could just “yeah money doesn’t matter you should be happy” your way out of it. Why is it necessary to choose a life path of crimes and prostitution? Why is it necessary to Izuru-fy oneself? It’s the perpetual predicament of mutual understanding in humankind. No matter how sweet and wholesome on the surface that ship appeared, Nanami would hardly ever reach Hinata’s soul beyond skin-deep, if the talent/worth debate, the rigorous societal expectations, the everlasting emotional quagmire of being under-loved and under-appreciated...everything which gradually carved out Hinata’s pivotal character (that we know of) from his embryo, was a non-issue to Nanami at core.

If there was a portion of Hinata yearning for true connection in an intimate relationship (which I doubt he didn’t), his relationship with Nanami would eventually turn insufficient or dissatisfactory, despite feeling nice on the exterior.

Normally, people don’t realize they’re empty until they’re fulfilled.

But who else struggled immensely with the entanglement between talent and worth throughout their life? Who else once resolved to obliterate their own precious being in pursuit of an almost delusional ideal of hope as Hinata did, so that they could potentially speak to Hinata on the deepest, hidden stratum of his soul?

Komaeda.

It always pains me to read Komaeda’s first FTE where he suggested Hinata’s ultimate talent could be “Ultimate Serenity” because Hinata granted him some inner peace “just by being there”. Knowing Komaeda’s mind it’s a nearly impossible feat to make him feel peaceful. Komaeda likely didn’t even consider that a legitimate talent, he inwardly viewed Hinata “being there” as inherently valuable but he couldn’t even tell. Yet Hinata failed to just, be there, be existent.

And, I always considered Komaeda sustaining himself being alive to be a monument on its own, yet 2-5 happened, for Hope, I believed.

I once had a mentally stimulating talk about how emotional and intellectual transparency lead to a solid foundation of “true love” among people with someone before. They even expressed, months ago, that if Hinata could just speak up about his problems with Nanami he wouldn’t have necessarily Izuru-fied himself.

Yet even being the aloof and reserved fucker he was, Hinata wouldn’t camouflage himself in front of Komaeda. Komaeda saw through him even if he was having a hard time deciding on how he should have felt himself. He voiced, various times throughout DR2, that “we have similar scents” “I thought you would understand me” “we’re both miserable bystanders” “I couldn’t see you as completely separate from me”. On the surface it seemed like Komaeda was being cryptic and dragging Hinata to his level, but given how we knew Hinata took even more drastic measures as escapism, were they even that different?

It was why exactly Komahina dynamic was so embittered and resentful in the canon timeline. It was not hatred, but involuntary intimacy. Hinata was emotionally stripped naked (sorry, not to evoke any erotic visualizations, just a convenient metaphor) when it’s not even Komaeda’s intention, and Komaeda’s always emotionally naked. It didn’t turn out well not because it was a fundamentally dysfunctional dynamic, but they simply met each other in the worst, most despairful and unluckiest timeline possible. With continuous manslaughters ongoing, it’s only palpable that baring your soul to someone as dangerous as Komaeda would be intimidating, but it still had that mesmerizingly entrancing aura, especially in Komaeda’s last FTE.

They had no choice of not knowing each other well.

Unless either of them died, which they both did. But an ultimate future was born and they were granted a second chance to finally reach the destination they deserved.

In a post-HPA scenario, Komahina was not only somewhat contextually implied as Hinata’s endgame, but it was deliberately set up as a generally hopeful relationship as well. Kodaka once suggested in an interview that post-HPA Hajizuru inherited Hinata’s emotions, so that he was able to sort out his considerably complex feelings for Komaeda as it left off; meanwhile with Izuru’s analytical skills and insights into human psychology, it would likely become not as cumbersome. With Hinata’s determination and persistence it would hopefully not only cure Komaeda’s terminal illnesses, but also “heal” Komaeda from his hope fetish and other cruddy coping mechanisms, with all the support and dedication Hinata could provide. Hinata, being emotionally identical to his past self, would likely occasionally experience insecurity and low self-esteem as well, and it could require Komaeda’s weird little method of presenting challenges/creating minor inconveniences for Hinata in order to help him build up self-agency and develop infallible self-assurance.

It’s kind of the Ultimate Love that survived all the trials and tribulations, and to think of that the Ultimate Tragedy gave birth to the Ultimate Love, huh, seems about right for our two Ultimate Lucks.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avatar: The Last Airbender DS Game Review

no one asked for this but i don’t ever see anyone talk about the atla videogames, which is a true tragedy, and i know that this may be because the video games aren’t technically canon, but i think they’re still worth talking about!

i finished this game in about three days, and i’m going to be talking about its gameplay, graphics, and story, all in that order.

spoilers below, as i’ll be talking about the entire game in depth.

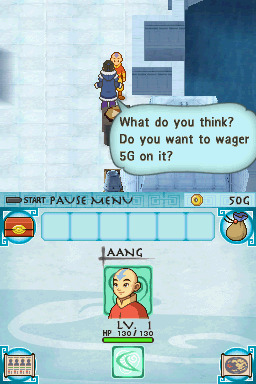

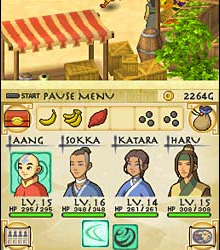

Gameplay:

the bulk of the gameplay consists of controlling your party of four, which consists of aang, sokka, katara, and haru. you can swap between any member of your party at any time using the touchscreen. you can run around with the d-pad, and you can also walk by holding down the b button. but onto the combat- each member has a specific set of attacks they can use, with two kinds of attacks and defenses, primaries and specials, with attacks assigned to the y and x buttons, and defenses assigned to the b and a buttons respectively. the game is jrpg-esque, in the sense that it has (somewhat) random encounters and a multi-person party, each with strengths and weaknesses. the random encounters aren’t fully random, as the enemies (which range from animals to machines) can be easily spotted and avoided in the overworld, but they do chase the party down. there is no in-game option to run from any random encounter, as you have to purchase smoke balls to run away from a fight. each random encounter will either drop a healing item or an unspecified amount of gold, which can be used in shops.

the game works in “chapters”, similar to the actual show’s structure, which has episodes, each of which start you and your party in/near a village, according to whatever setting the plot deems necessary. in each village, there is a variety of shops, which include an herbalist, medicine man, and fruit seller. the herbalist will mix together any random herbs you find (for a fee) in the overworld, creating single use status-buffing items that have varying effects based on the kinds of herbs used. the medicine man (unsure if that’s what he’s actually called) will sell incense and smoke bombs, with the latter used to control the rest of the party, with different kinds of incense used to dictate their behavior in battle. for example, defense incense will make the rest of your party use more defensive moves, rather than offensive. the fruit seller sells various healing items, which range between single and party-healing. as the game progresses, these items grow more and more costly, requiring increasing amounts of gold. there are also hidden item boxes, though these are found in both the villages and world itself. items can be held in a sizeable inventory, but items must manually be moved up into a six-slot hotbar for use during combat.

though the bulk of the gameplay is exploration and fighting, there are also some smaller parts within the game that switch it up a bit. there are minigames, such as four nations force, which can be found in villages and is a pai-sho-esque game with similar tiles, as well as opportunities to train certain members of the party, namely haru (at least in my experience). there is a segment in which you can control momo, and have him solve a puzzle to open a door, and in that same segment, there is a mission where you have to utilize the b-button to silently walk past guards. there are a few of fetch-quests, though they aren’t too difficult, and drive the plot forward.

the gameplay isn’t anything groundbreaking or spectacular, but it serves its purpose well, and can make for some really fun strategy-driven moments where you have to constantly swap between characters to see if there’s advantages to using one over the other, and rationing out health items carefully to see if they’ll last you before a boss fight. there’s definitely a lot of combat, and, while the game doesn’t force you to, there is the inherent expectation of level-grinding, which can make certain segments of the game a whole lot easier, especially with unlocked specials and higher power. there is also the fact that, should you lose a random encounter fight with no smoke bombs, you are basically stuck in the fight until you win or quit, which are the only two options. furthermore, should you quit, you’ll be sent back to your last save, and you must manually save, as is standard for most games of this era, as it only prompts you to save at the very conclusion of a chapter. there is a bit of mercy, however- should your entire party die and you continue, your party’s health will be restored to at least a third, and all items used in the previous battle will return in your inventory, ready to be used again.

Graphics:

as is expected with ds games of this era, the characters are rendered in charming little pixel sprites, which each sprite being beautifully animated and full of personality. in cutscenes, each character emotes with their own set of sprites, and their mouths are animated when they talk. sometimes, their sprites are used for comedic effect- there are rarely moments where characters are just standing and spewing dialogue. there are also pixel-rendered portraits of each character in the party on the touchscreen, allowing you to see their health, moves, and level.

what’s interesting about this game, however, is that, while the characters are 2d sprites, their surroundings are 3d, and you can change the viewpoint of the camera at any time in the overworld with the l and r bumpers, allowing you to really see the entirety of the map. this makes exploring all the more interesting, as you can spin the camera around to see hidden loot boxes or other items you may have missed. in villages, there is a lot of new personality and depth given to each setting, especially familiar sights from the show such as omashu and the northern air temple. the aesthetic of the overall show is kept intact well, as even the npcs in new towns all appear to fit by design, and there is a sense of visual cohesion that makes it feel true to its roots. there are little nods to canon beyond just the main characters, such as one of the healing items in the game being a custard tart, and town designs expanding on already established settings.

each segment of the game carries with it a unique feel, making each chapter easily distinguishable from the last. the game has so much charm, with its bright visual styles and faithfulness to its canon inspiration, and each setting is unique and fun to explore. the only thing that may bog it down in terms of both gameplay and graphics is that a majority of the surrounding buildings in villages and cities can’t be entered nor explored- they’re just props. this gives a slightly empty vibe to the environment when you notice that the background props are just props. it would be much more fun to explore the given environment if there was more to do, rather than just the same three to five things. furthermore, while the camera function is very useful, it can also be really confusing in terms of navigation. there’s a map and a compass, sure, but sometimes you’ll be stuck spinning the camera until you’re absolutely sure you’re headed in the right direction. the map, at least, does give you an indicator on where you’re supposed to go next to advance the plot, and there is a similar kind on the compass as well, which helps immensely.

Story:

unlike other games (namely burning earth and into the inferno), this game’s plot is mostly standalone, and doesn’t follow the canon timeline very closely. there is less “a game about playing through the show’s events”, and more of “a game that uses canon elements to create a story of its own”. the story, which doesn’t fully fit within the bounds of canon, is still an interesting story to present nonetheless.

spoilers for the entire story begin here!

the story opens with aang, katara, and sokka in the north pole, where master pakku has been mysteriously replaced with a character named master wei, who tells the gaang that one of their waterbenders, named hiryu, has vanished. upon further investigation, a waterskin and a weird piece of metal is discovered where the waterbender was seen last- however, these investigations are quickly halted by the arrival of zuko and the fire nation, who kidnap katara as bait for aang. sokka and aang track her down to a fire nation prison, where they have to dress up as fire nation soldiers in order to sneak in and get info on her whereabouts in order to save her. while saving katara, they also discover another prisoner named lian, who is presumably being forced to work for the fire nation. after a brief battle with the warden, they find that lian has escaped on her own, and left a note behind, pointing them in the direction of an earth kingdom village.

after katara has been saved and the gaang follows the note, they find the village being terrorized by mysterious machines with the ability to bend/use singular elements, though they are being fended off by two earthbenders. upon further investigation, the earthbenders turn out to be tyro and haru, who were saving villages when this one was attacked by machines. after defeating the machines, the gaang learns from tyro that another bender has been kidnapped- an earthbender named yuan, who was one of haru’s closest friends. because of this, tyro encourages haru to join the gaang’s quest to find out where the machines are coming from, and points them towards the forest for clues, as a wise spirit resides there. the party then encounters a bear-like creature, which attacks them, though upon defeat, reveals itself to be the forest spirit, who gives them very cryptic answers when asked about the origins of the machines, saying something related to the heart of the earth kingdom.

somehow, this prompts the gaang (now joined by haru) to go to omashu, as it’s in the heart of the earth kingdom. aang decides to ask his friend king bumi to help them figure out where they need to go to find the origins of the machines, and the king, while happy to see his friends again, is forbidden from helping the group discover secrets, due to his royal counsul, who refuses to let them go to where they need to go. nevertheless, bumi directs them towards the earth kingdom royal library, where a scroll is found showing a series of bending techniques, as well as some kind of map. upon bringing their findings to king bumi, he points them in the direction of four paws island- an unmarked island off the coast of the earth kingdom. however, as the gaang prepares to leave, the fire nation attacks once more, forcing them to find an alternate route out of the city, where they are challenged by the royal counsul, who is revealed to be conspiring with someone relating to the machines. haru, enraged by the counsul’s traitorous actions, takes him on one on one, and, upon defeat, allows the gaang to escape to four paws island.

now on four paws island, the party finds more mysteries than they bargained for, as there are more machines terrorizing the people of four paws, as well as more benders going missing. unsure where to start, they begin to search the island for a statue they recognized from the royal library, soon discovering a hidden passageway underneath it that leads them to a model of the island itself, which holds a mysterious blue rock. the rock, covered in old writing, is then brought to the elder of the village, who reveals that it holds the entire history of four paws, and also serves as a key to a secret passageway. the passageway, which is discovered in the side of a cliff west of the village, is revealed to be a sprawling, underground lair, crawling with machines. at the end of it, a large machine sits in wait as a familiar face operates on it. the person reveals themselves to be lian, who has been building the machines in hopes of restoring peace to the world. the machines, she hopes, will wipe out and replace benders, thus evening the playing field, as the very existence of benders creates divide between people and nations. she worked with the fire nation solely to gain resources for her machines, as well as the omashu royal counsul, and she tries to persuade aang to join her, stating that he will never be ready to fight ozai. aang refuses, along with the rest of the gaang, and, in a fit of rage, she states that she will cut off his connection to the avatar state and unleashes her prototype bending machine on them, which uses three of the four elements to attack. upon defeat of the machine, the gaang rushes to catch lian before she can escape again.

the group now lands at an earth kingdom village that borders the air temples, and aang decides to take appa head off on his own towards the northern air temple, knowing that lian will most likely head there and destroy the avatar statues, mistakenly believing that this action will sever his ties to the spirit world. the story then alternates between aang at the air temple, and katara, sokka, and haru back at the village. while aang fights off machines and tries to protect the air temple from destruction, the rest of the group fights off machines in the forest, where the people from the village were trying to rebuild. after defeating the machines, however, a mysterious large machine appears, and katara, sokka, and haru are taken. when aang arrives back at the village after successfully protecting the temple, he is attacked by a drill-like machine, and has to destroy it on his own. upon defeating the machine, he discovers a large hole/tunnel in the ground, and decides to follow it, hoping it’ll lead him to his friends.

the tunnel leads aang to another village, where a large temple resides in the northwest that villagers refuse to enter, due to benders mysteriously disappearing around there. aang, after battling his way through the surrounding forest, enters the temple and discovers his friends imprisoned there by lian, and he is forced to save each of them separately. sokka is found trapped in a strung up cage, and he discovers a tool left behind by lian, which he uses to open locked doors within the temple. katara is inexplicably found on the other side of a large lava pit, and aang must fly across it to save her. haru is found in a metal prison below the temple, and, after being feed by sokka, tells the rest of the gaang where lian is headed. now fully reunited, the group heads towards the heart of the temple, which is blocked by a series of large rocks that haru makes quick work of, and they prepare to stop lian.

before stopping lian, however, the group discovers zuko, who lays injured on a bridge. aang, who runs to help him, asks if he needs help and assumes he was captured by lian as well, but zuko refuses to accept his help, instead berating the fire nation for trusting lian and her nefarious machines. the gaang reassures zuko that they will do something about the machines, but are forced to leave him behind, unable to do anything to save him at the time, despite aang’s protests. the group then falls for a trap, which unleashes an even stronger version of the prototype bending machine from before, which now has the ability to freeze water, and is forced to destroy it before they can continue. after the ensuing battle, aang, sokka, katara, and haru finally prepare to confront lian for the final time.

lian, standing in front of a powerful machine with the ability to use all four of the elements, is found alongside two other benders- hiryu and yuan, who are revealed to be working with and for lian, teaching her machines their bending techniques, as they support and believe in their cause, rather than held against their will, as originally believed. this upsets haru, who tries to convince yuan to join their group, to no avail. lian repeats her speech on division between the four nations and elements, stating that she would rather have thinkers in charge of the world, rather than magicians. she gives the group one more chance to join her side, lest they be eliminated by her ‘avatar’ machine, stating that benders such as yuan that side with her cause will be spared, and that benders such as zuko who refuse will suffer the consequences. aang, who firmly believes that zuko didn’t make the wrong choice, states that being the avatar is something that can’t be replaced by machines, and he and the rest of the party ultimately challenge and prepare to destroy her ‘avatar’ machine.

midway through the fight, however, a fireball is shot at aang, which none of the group sees except for katara, and she throws herself in front of it, taking the hit for aang. while the rest of the group rushes to her aid, lian mocks the group for being weak, showing that this is proof that her machine is stronger than all benders. enraged, aang enters the avatar state, facing the machine alone and destroying it quickly, soon passing out from exhausion once the fight ends. unlike in other iterations of this same game, lian survives and is helped by hiryu and yuan, who realize the consequences of their mistakes and elect to help lian and improve themselves. escaping as sokka and haru care for aang and katara.

aang eventually reawakens in katara’s arms, and sokka gets angry with katara putting her life on the line for aang, but katara says that she had to do something, as aang is important to not only the world, but her as well. aang learns that this message is applicable to his role as the avatar, realizing that he has a responsibility to help when no one else can, and he must accept his role in the world. soon, the group escapes the fortress over to appa and momo, and begin heading back to haru’s village, bringing him home before starting back off on aang’s quest to learn all four elements. zuko is also revealed to have escaped the fortress, and is upset that he missed his opportunity to capture the avatar.

spoilers for the entire story end here!

the story is extremely simple, yet chaming and full of twists. it’s definitely not something one would expect from atla’s usual fare, especially considering the technology and themes, but it still fits pretty well. lian is an interesting and dynamic villain, and her motivations are presented in a believable manner, and she makes for a pretty sizeable threat over the course of the story. the dialogue and cutscenes are generally entertaining, and the story is fun to watch unravel. the only things i personally took issue with were the pacing and some character inconsistencies. there’s a segment in omashu that’s a bunch of fetch quests that lead up to a joke, and, while the joke is pretty funny, bogs the pacing down a lot. there’s also no sidequests whatsoever (barring the singular one in the north), and there is no way to go back to a previous chapter, so you have to accomplish every single thing you want to accomplish before moving forward. the story is extremely linear, which works well, but i found myself wanting more, especially in the character department. surprisingly, haru works extremely well as a member of the gaang, and i found his interactions with them to be entertaining and fun to watch. it’s cool to have an atla piece of media that not only remembers him, but makes him an actual character. however, there’s not much for character on character interactions, even with all the cutscenes. i wanted to see more of this new gaang being friends, since it presented an entirely different dynamic from the show. there’s also the issue of some interactions feeling pretty flat, such as haru being imprisoned again and having no reaction to it, or sokka not being given much depth outside of being the butt of many jokes (outside of the one scene with the kid and the boomerang), but these are minor gripes in the face of the characters and story it presented. overall, i think the only big thing i have to complain about is the ending, which was changed from the original ending, where lian ambiguously dies and haru and yuan reconcile. it feels like a last ditch attempt to redeem lian and yuan, which i understand to some extend, but it feels extremely out of place and put in at the last moment. this also downplays haru and yuan, which is sad considering that yuan getting captured is what leads haru to join the adventure in the first place.

In Summary:

7.5/10. it’s a fun game with some difficulty spikes and a genuinely enjoyable story. i know that most tv show videogames don’t have a great reputation, so i think this was pretty good compared to what i’ve played before. the main things that keep it from being a 10/10 for me was the realization that the game wanted me to grind, lack of extra content that would’ve heightened the experience, some story and character snags, and rather repetitive boss fights. i took off an entire .5 for the fight with the spirit bear, which was a really infuriating experience (that was largely my own fault as i walked in unprepared), but other than that, i would genuinely recommend this game to anyone who wants a fun time with well-made spinoff videogame.

#this got way longer than i intended#long post#sorry guys i just had to recap this game in detail#no one else would#also for anyone wondering the characters i used the most were aang and haru#i liked all of aang's specials and well#we all know that i love haru so#now! onto burning earth!#hope you guys enjoyed this lengthy review#atla#avatar the last airbender#atla ds game#avatar the last airbender ds game#atla game#atla videogame#aang#atla aang#aang atla#katara#atla katara#katara atla#sokka#sokka atla#atla sokka#haru#atla haru#haru atla#lian#atla lian#lian atla

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Absurdity and Remembrance: How Mental and Physical Spaces are Forms of Resistance

It is only the absurd that shows the presence of what is human – Doris Salcedo, a Colobian visual artist, quotes post-war poet Paul Celan when she describes the detailed, labor-some, and seemingly ‘absurd’ artistic processes that precede her final installations. The absurdity she references is related to the unique complexity of her work. Salcedo’s pieces are layered – to a viewer at first, a table looks like a table, shoes in the wall are simply observed as they are, and a 500-foot crack in the floor of Tate Modern appears to be a random art idea (if not completely disregarded as an art piece.) However, closer analysis reveals human hairs sown into the wood table, shoes pressed into a wall behind animal skin, and the technicalities of the prodigious crack that probably necessitated many complex design decisions. Salcedo describes these processes as absurd, as many of these seemingly ‘simple’ pieces were produced after year-long endeavors. However, it seems that the absurdity is somewhat intentional, exposing the human experience intrinsic to its creation. In fact, her process and pieces seek to subtly yet powerfully validate traumatic, often invisible lived experiences that she bears witness to[1]. Her final installations, then, are physical manifestations of this absurdity, the material objects that are testaments to remnants of collective trauma, telling untold stories slowly, carefully, absurdly, to achieve a semblance of collective justice. Salcedo addresses social justice by constructing both mental and physical spaces for grief/mourning, the former through seemingly 'absurd' aesthetic methods, and the latter through the physical arrangement of installations. Salcedo's labor-some artistic processes actually dramatizes and makes visible absurdity/futility/illogicality and uses it as a vehicle to expose forgotten histories that are a consequence of State violence. The finished pieces are physically glaring hints at how violence manifests. Therefore, the forgotten invisible is transformed into mental and physical visible space. In order to prove this end, this paper will first offer brief visual analyses and an explanation of Salcedo’s methodologies. Next, it will analyze how her intricate process constructs mental space, and how her physical pieces are a product of those intricacies. Finally, it will explore relevant concepts of decoloniality and Salcedo’s own viewpoints on true ‘justice.’

As mentioned previously, since the process and labor of art-making give her final pieces their meaning, it will be important to be historically situated and visually analyze the installations Unland: The Orphan’s Tunic (1997)[2]and Atrabiliarios (1992/2004)[3] in terms of appearance and creative development. Salcedo’s process begins with interviewing victims of violence in Colombia conflict zones, where the ‘political killings’ carried out by the military squads has caused traumatic State-inflicted violence[4]. Through this, she discovered that women were subjected to extreme brutality in Colombia[5]. Her practice is a direct response to military regimens in Colombia responsible for massacres. She aims to amplify the loss of human bodies by using body parts (like human hair) after subjection to State-inflicted violence. She acts as a listening witness to these testimonies, taking years to create objects that most accurately (yet subtly) depict the violence.

Unland: The Orphan’s Tunic (1997) is an example of her efforts. It is a rectangular arrangement made of two wood tables somewhat unevenly placed together. One table is oak-colored, the other appears white, and the difference in color is stark. Between the two tables, small holes were drilled – human hair and raw silk were threaded through and sown[6]. As Salcedo describes in the interview (Module 3), the project took over a year to finish. As a continuous piece, the ‘uneven’ quality of the table makes it look used, unfinished, and held together by only the sewn hair. Cathy Park Hong describes that the “object [is] all used, rubbed down and softened by the bodies that have handled, lain, and sat on them for years[7]”. Hong suggests that the piece is a representation of lived and ‘handled’ space that is now left behind. She also states that the presence of threaded hair is “like cryptic inscriptions from the dead", highlighting the remnants of an uneasy, lived experience that is no more. The thin, sown hairs hold the distorted tables together, as if subtly grieving that their broken existence cannot be mended because it resides in a permanently disrupted state. As put by Daryl Chin, the hairs were taken from actual people Salcedo interviewed that were victims of violence. Thus “this removal can be seen as an example of violence, however miniscule[8] - It is a removal meant to showcase the remnants of violence, and perhaps how broken families, bodies, and traumas can be perpetually fragmented. Even the title “Unland”, through negating the word ‘land’, hints at the idea that the horrors inflicted on these people is in a place that only exists as a fragment, as an unfinished story. Similarly, Atrabilirios (1992-2004) is an installation art made by forming multiple square indents in a plain white wall. Women’s shoes, either single or in pairs, are placed in the wall standing up. They are covered by a sheet of animal fibers which are affixed to the wall using multiple stitches, but the shoes are still slightly visible – No other clothing is part of the art piece. As an entire installation, they are striking against an all-white background. The animal skin serves as a separative force between the viewer and the shoes that, according to Salcedo and Dan Cameron, “creates a strangely tactile sensation that invokes the shoes’ missing owners with chilling familiarity[9]”. The aforementioned description suggests that the shoes serve as reminders of the past intended to cause momentary discomfort and awareness in the viewer that the shoes are ‘missing’ from a woman who once was. Hyper-visible against the wall, it is a historical reality of violence against women and the disappearance of bodies, uncovered by a seemingly every-day object (shoes) that can never be returned because they were left behind, perhaps making the viewer ask what was made of the other worn items?

The visual analyses provided that have ‘absurd’ procedural elements intrinsic to them will serve to emphasize how mental and physical spaces were constructed by Salcedo to expose the stories of political violence she bore witness to. Mental space was made through artistic labor, an endeavor that is seemingly ‘absurd’ and unnecessary given the relative simplicity of the final installations (but is intentionally so.) In the case of Unland: The Orphan’s Tunic, sewing hair into wood was achieved through multiple volunteers working together with Salcedo – the process was thus time-consuming (make it inherently laborious.) In an interview, one of her volunteers said that while he was drilling holes into the table, he heard gunshots and saw blood in the streets. He stated, “Suddenly you understand why you have to make millions of holes and it was not rational, but it makes sense in that moment.”[10] The volunteer highlights that his ‘irrational’ labor was justified in that moment because it almost directly counteracted the real, also absurd violence occurring outside. Making mental space and time to counterbalance this absurdity (by using absurdity in a different strain) “made sense”, like a long mourning journey that was immediately necessary to be undertaken. Additionally, taken alone, the act of sewing into a table is uncommon, so it comes across as ‘absurd’. The method may seem inefficient or even futile – For example, why did Salcedo not elect to use machinery to sow? Why did she not sow into cloth instead of wood? Therefore, through investments in time and ‘inefficient’ methods, Salcedo mentally processed the trauma of the victims she interviewed. She showed up to work on an ‘absurd’ project for years, remembering every day the stories of those who suffered under military power and dictatorship. The physical installation is an illustration of this labor, even more striking because the final piece is minimalistic. Salcedo thus dramatizes absurdity in a way that turns invisible violence and trauma into hyper-visible mental and physical space. By the same logic, shoes in a wall standing up and not flat on the ground (Atrabilirios) is an unnatural, absurd physical placement. The mental space is made in the viewer upon recognition of their discomfort with placement, location, and the nonexistence of other clothing. Once again, Salcedo dramatizes absurdity to make visible a physical state of reversal from the norm and the subsequent mental discomfort.

It will now be appropriate to consider notions of decoloniality – Salcedo’s practice was partly decolonial because it seeked to validate ways of being that were disrupted by violence, but not particularly decolonial because of Salcedo’s comment that art cannot save (interview, module 3). Catherine Walsh, as stated in Lecture 1A, defines decoloniality as “modes of thinking, knowing, and being that often precede colonial invasion. Decoloniality is a form of struggle and of survival practices by those who have been colonized responding to the colonial matrix of power[11]”. By this definition, Salcedo’s work is decolonial because it highlights ‘modes of being’ that precede colonial invasion/violence/disturbance. These modes included emphasizing hair and shoes as remnants of being before disruption. However, it is not decolonial in all regards because Salcedo describes her work as ‘impotent’ – she believes her work is futile, that it cannot fix any problems. Walsh’s definition of decoloniality is more active, stating that there are practices that respond to matrices of power. However, Salcedo’s practice itself is subtle and does not seek to respond or fix, but simply to depict reality in a subtle way. There is no practice of struggle or survival, because the work always already acknowledges that struggle/survival were impossible against violence. Salcedo simply listens, creates, and lets the artwork represent a forgotten reality. Such an analysis ties in to whether or not Salcedo is conducting social justice “work”. Justice is a layered term because it often assumes a sort of reparation for wrongdoing. In the same interview, Salcedo mentions that “life is wasted but you can build something poetic.” Salcedo does not believe that “art can save” and believes that the lives were truly ‘wasted’ away by violence. The unfinished pieces and odd arrangements seem to signify a permanent state of grief/mourning. Thus the artist only wants to flip the terms of normalcy and logicality in her practice to make visible the invisible – Such an act acknowledges that ‘true’ justice cannot be attained.

Salcedo inhabits and creates mental and physical spaces that are ‘absurd’, and magnifies this absurdity in order to expose violence in Colombia. For example, she seeks to remind viewers of death by amplifying loss and exaggerating remnants of people murdered by the State. Mental space is made through labor and time, while the final piece is a product of these endeavors. In all, her efforts were necessary to be done in vain, with no immediate purpose, to illustrate a larger significance. Her art exposed residues of violence without depicting real bodies or actual scenes. Perhaps it reminds viewers of how the most disturbing part of death is not the gruesome portrayal of it. It is a worn shoe sitting in the closet that has no owner anymore, the hair that does not have a head, the subtle remnants of life that remind of what once was. Salcedo’s art has this kind of effect, reminding spectators of truly absurd every-day realities. Her work demonstrates that ‘true’ social justice (as close as one can get) is not acquired simply through surface-level recognition or reparation, but by ongoing (and often grueling) forms of resistance and remembrance. It is ultimately true, then, that the presence of the absurd shows the presence of the human.

Title: Unland: The Orphan’s Tunic (1997) – Art installation

Artist: Doris Salcedo

Title: Atrabilirios (1992-2004) – Art installation

Artist: Doris Salcedo

References

[1] Interview with Doris Salcedo. Doris Salcedo in “Compassion” on art 21, season 5, October 7, 2019. [2] Orphan’s tunic 1997 (see picture with caption below) [3] Defiances 1992 (see picture with caption below) [4] Doris Salcedo and Dan Cameron, “Unland”, Jean Stein on Jstor Vol. 61: page 81 [7] Cathy Park Hong, “Against Witness”, Poetry on Jstor Vol. 206, Issue 02: pages 151-157, https://www-jstor-org.oca.ucsc.edu/stable/pdf/43592005.pdf?ab_segments=0%252Fdefault-2%252Fcontrol&refreqid=excelsior%3Aeec33449b0b72533ead27990af525345 [8] Daryl Chin, “Beau Geste”, PAJ Publications on Jstor, Vol. 20, Issue 02: pp. 57-61, https://www-jstor-org.oca.ucsc.edu/stable/pdf/3245930.pdf?ab_segments=0%252Fdefault-2%252Fcontrol&refreqid=excelsior%3Af829f137a79aab93c3d09e33b0c676ee [9] Doris Salcedo and Dan Cameron, “Unland”, Jean Stein on Jstor Vol. 61: page 81, https://www-jstor-org.oca.ucsc.edu/stable/pdf/25000098.pdf?ab_segments=0%252Fdefault-2%252Fcontrol&refreqid=excelsior%3A0959a2c8f7d815b429368b33c286abbb [10] Interview with Doris Salcedo. Doris Salcedo in “Compassion” on art 21, season 5, October 7, 2019. [11] Rosa, Tatiane. “Lecture 1A – Deconstructing the Category “Latin America” – What does it mean to decolonize?” Class lecture, HAVC 144A from University of California, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, June 30, 2019.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

New Post has been published on https://warmdevs.com/intelligent-assistants-have-poor-usability-a-user-study-of-alexa-google-assistant-and-siri.html

Intelligent Assistants Have Poor Usability: A User Study of Alexa, Google Assistant, and Siri

The holy grail of usability is to build an interface that requires zero interaction cost: being able to fulfill users’ needs without having them do anything. While interface design is still far from reading people’s minds, intelligent assistants such as Alexa, Google Assistant, and Siri are one step in that direction.

UI Characteristics

The intelligent computer-based assistants combine 5 fundamental user-interface technologies:

Voice input: commands are spoken instead of issued through typing or clicking/tapping graphical items.

Natural-language understanding: users are not restricted to using a specific, computer-optimized vocabulary or syntax, but can structure their input in many ways, just as they would do in human conversation.

Voice output: instead of displaying information on a screen, the assistant reads it out loud.

Intelligent interpretation: the assistant utilizes additional information (such as context or past behaviors), besides the user’s literal input, to estimate what the user wants.

Agency: the assistant does actions that the user hasn’t requested, but which the computer undertakes on its own.

Both intelligent interpretation and agency require that assistants actively learn about the user and be able to modify their behavior in the service of the user.

Thus, when evaluating the user experience of intelligent assistants, we need to consider 6 issues: each of the 5 technologies, plus their integration.

The idea of integrating a bundle of UI technologies isn’t new. The same principle is behind the most popular style of graphical user interfaces (GUIs), called WIMP for “windows–icons–menus–pointing device”. You can have windows without a mouse (use Alt-Tab) or a mouse without icons (click on words), but the full set generates a nicely integrated GUI that has offered good usability for more than 30 years.

Not all assistants use all 5 UI technologies at all times: for example, if a screen is available, assistants may use visual output instead of voice output. However, the 5 technologies support and augment each other when they are smoothly integrated. For instance, voice commands, like the traditional command-based interaction style, have an inherent usability weakness compared to clicking (they rely on some amount of recall, whereas clicking and direct manipulation involve recognition), but natural language may potentially make composing a command less arduous than clicking an icon.

Integrating the 5 UI techniques promises an interaction style with two advantages:

It can short-circuit the physical interface and simply allow users to formulate their goal in natural language. Although speaking does involve an interaction cost, in theory this cost is smaller than learning a new UI, pressing buttons, and making selections.

It can infer users’ goals and be proactive about them by offering appropriate suggestions based on contextual information or prior user behavior. This second aspect is in fact closer to “reading our minds.”

Contextual suggestions are still fairly limited with today’s assistants, although small steps are taken in that direction — Google Assistant parses email and adds flights or restaurant reservations to calendars; and both Siri and Google Assistant warn users of the time it takes to get to a frequent destination once they leave a location. When these contextual suggestions are appropriate, they seamlessly progress users towards their goals.

User Research

To better understand what challenges these assistants pose today and where they help users, we ran two usability studies (one in New York City and one in the San Francisco Bay Area). A total of 17 participants — 5 in New York, 12 in California — who were frequent users of at least one of the major intelligent assistants (Alexa, Google Assistant, and Siri) were invited into the lab for individual sessions. Each session consisted of a combination of usability testing (in which participants completed facilitator-assigned tasks using Alexa, Google Assistant, or Siri) and an interview.

During the usability-testing portion of the study, we asked participants to use the assistants to complete a variety of tasks, ranging from simple (e.g., weather for the 4th of July weekend, pharmacy hours for a nearby Walgreens, when George Clooney was born) to more complicated (e.g., the year when Stanley Kubrick’s second to last movie was made, traffic to Moss Beach during the weekend).

This article summarizes our main findings. A second article will discuss the social dimension of the interaction with intelligent assistants.

Results: Delivered Usability Grossly Inferior to Promised Usability

Our user research found that current intelligent assistants fail on all 6 questions (5 technologies plus integration), resulting in an overall usability level that’s close to useless for even slightly complex interactions. For simple interactions, the devices do meet the bare minimum usability requirements. Even though it goes against the basic premise of human-centered design, users have to train themselves to understand when an intelligent assistant will be useful and when it’s better to avoid using it.

Our ideology has always been that computers should adapt to humans, not the other way around. The promise of AI is exactly one of high adaptability, but we didn’t see that that when observing actual use. In contrast, observing users struggle with the AI interfaces felt like a return to the dark ages of the 1970s: the need to memorize cryptic commands, oppressive modes, confusing content, inflexible interactions — basically an unpleasant user experience.

Let’s look at each of the 6 UI techniques and assess how well they met their promise to our users. While the answers to this question are sad, we can also ask whether the current weaknesses are inherent to the techniques and will remain, or whether they are caused by current technology limitations and will improve.

UI technique Current usability Future potential Voice input Good (except for nonnative speakers) Soon to be great and also cope with accents Most of the input is correctly transcribed, with the occasional exception of names. Natural language Bad Can become much better, but hard to do Multiclause sentences are not understood; equivalent query formulations produce different results. There is limited understanding of pronoun referents. Voice output Bad Inherently limited usability, except for simple information Except for a few tasks (e.g., navigation, weather), the assistants are not able to consistently produce a satisfactory vocal response to queries. Intelligent interpretation Bad Can become much better, but extremely difficult to do The assistants use simple contextual information such as current location, contact data, or past frequent locations, but rarely go beyond that. Agency Bad Can become much better There is only a very a limited use of external sources of information (such as calendar or email) to infer potential actions of interest to the user. Integration Terrible Can become much better, but requires much grunt work The assistants don’t work well with other available apps on the device and the interactions with various “skills” or “actions” don’t take advantage of all the UI technologies.

Are we being unreasonable? Isn’t it true that AI-based user interfaces have made huge progress in recent years? Yes, current AI products are better than many of the AI research systems of past decades. But the requirements for everyday use by average people are dramatically higher than the requirements for a graduate student demo. The demos we saw at academic conferences 20 years ago were impressive and held great promise for AI-based interactions. The current products are better, and yet don’t fulfill the promise.

The promise does remain, and people already get some use out of their intelligent assistants. But vast advances are required for this interaction style to support wider use with a high level of usability. An analogy is to the way mobile devices developed: when we tested mobile usability in 2000, the results were abysmal. Yet, the promise of mobile information services was clear and many people already made heavy use of a particularly useful low-end service: person-to-person text messages. It took many more years of technology advances and tighter UI integration for the first decent smartphone to ship, leading to an acceptable, though still low level of mobile usability by 2009. Another decade of improvements, and mobile user interfaces are now pretty good.

AI-based user interfaces may be slightly better than mobile usability was in 2000, but not by much. Will it take two decades to reach good AI usability? Some of the problems that need solving are so tough that this may even be an optimistic assessment. But just as with mobile, the benefits of AI-based UIs are big enough that even the halfway point (i.e., decent, but not good, usability) may be acceptable and could be within reach much sooner.

Why Do People Use Assistants

Most of our users reported that they use intelligent assistants in two types of situations:

When their hands were busy — for example, during driving or cooking

When asking the question was faster than typing it and reading through the results

The second situation deserves a discussion. Most people had clear expectations about what the assistants could do, and often said that they would not use an assistant for complex information needs. They felt that a query with one clear answer had a good chance of being answered correctly by the assistant, and two participants explicitly mentioned 5W1H (Who, What, Where, When, Why, How) questions. In contrast, more nuanced, research-like information needs were better addressed by a web search or some other interaction with screen-based device such as a phone or tablet.

However, some people felt that the assistants were capable of accomplishing even complicated tasks, provided that they were asked the right question. One user said “I can do everything I can do on my phone with Siri. […] Complex questions — I have to simplify to make them work.”

Most people however considered that thinking about the right question was not worth the effort. As one user put it, “Alexa is like an alien — I have to explain everything to it… It’s good only for simple queries. I have to tell her everything. I like to simply ask questions, not think [about how to formulate questions].”

One notable area where voice assistants saved interaction cost was dictation: long messages or search queries were easier to say than type, especially on mobile devices, where the tiny keyboard is error-prone, slow, and frustrating. Participants were usually quick to note that dictation was imperfect and helpful when they could not type easily (for example, because they were walking, driving, cooking, or simply away from a device with a real keyboard), and that they avoided dictation if the text used unique terminology that could mistranscribed. They also mentioned struggles with having the assistant insert the correct punctuation (either the assistant would stop listening if the user paused to denote a sentence end or the assistant simply would ignore punctuation altogether, requiring users to proofread and edit the text).

Speaking with Assistants

When participants took the time to think about how to formulate the query and then delivered it to the assistant in a continuous flow, the assistant was usually able to parse the whole query. As a user put it, “You should think of your question before you ask it — because it’s hard to fix it while you’re saying it to [an assistant]. You’ve just got to think of it beforehand, because it’s not like a person where in a conversation with them [you can be vague].” Another said, “I almost feel like a robot when I’m asking questions, because I have to say it in such a clear and concise way, and I have to think of it so clearly. When I try to give a command or ask a specific question, you don’t use much inflection. It’s really just picking up words, it’s not picking up emotions in your voice.”

But many participants started speaking before formulating the query completely (as you would normally do with a human), and occasionally paused searching for the best word. Such pauses are natural in conversation, but assistants did not interpret them correctly and often rushed to respond. Of course, answers to such incomplete queries were incorrect most of the time, and the overall effect was unpleasant: participants complained that they were interrupted, that the assistant “talked over them”, or that the assistant was “rude.” Some even went as far as to explicitly scold the assistant for it (“Alexa, that’s rude!”).

When people needed to restate a query that wasn’t understood correctly, they often enunciated words in a highly exaggerated way (as if they were talking to a human with a hearing impairment).

The majority of the participants felt that complex, multiclause sentences (such as “What time should I leave for Moss Beach on Saturday if I want to avoid traffic?” or “Find the flight status of a flight from London to Vancouver that leaves at 4:55pm today”) were unlikely to be understood by the assistants. Some tried to decompose such sentences in multiple queries. For example, one participant who wanted to find out when Kubrick’s second-to-last movie was made asked for a list of movies by Kubrick, and then planned to ask questions about the second-to-last item in that list. Unfortunately, Siri was not helpful at all, because it simply provided a subset of Kubrick’s movies, with no apparent order.

Nonnative English Speakers

Several people had foreign accents and felt that the assistant did not always get their utterances and had to repeat themselves often. These people were frustrated and considered that the assistants had to learn to deal with various languages and ways of speaking.

Besides the accent, there were three other factors that affected their success with assistants:

They were likely to pause even more in their utterances than native speakers. These pauses were often interpreted by the assistant as the end of the query.

They tended to correct themselves when they felt that they had mispronounced a word and ended up saying the same word twice. These repeated words seemed to confuse assistants — especially Alexa.

They sometimes used less common wordings. For example, one participant asked “Alexa, when did Great Britain’s soccer team play in the soccer championship.” Alexa was not able to find an answer for that question.

Luckily, accent comprehension is an area where computers have the potential to be better than reality: they can recognize non-standard pronunciations of words much better than a human can do. A computer doesn’t care how you pronounce a certain word — unless it’s trained to only recognize a specific sound, it can be made to understand that several different sounds all represent the same word. Thus, we expect that better accent recognition is only a matter of time. Coping with the other issues discussed in this section will be harder.

Presenting Answers

Assistant’s Language

Some of the participants complained that the assistant spoke too fast and that there was no way to make it repeat the answer. Especially when the answer was too long or complex, participants could not commit all the information to their working memory. For example, before offering a mortgage quote, the Alexa Lending Tree skill asked the user to confirm that all the details entered were correct by reciting the address and the mortgage terms, and then enumerating a set of commands for editing the information if needed. One user said: “It’s talking too fast at the very end — [it says] `if something is not correct [you have to] go to bla bla bla’; it’s just too hard to remember all the options.”

When the assistants misunderstood the question and offered an incorrect response, the experience was off-putting and annoying. People resented having to wait for a long answer that was completely irrelevant and struggled to insert an “Alexa, stop” in the conversation. One participant explained, “What I don’t like is that [Alexa] doesn’t shut up when I start talking to her. This is what a more human interaction should be. […] It would be ideal if it interacted to something less than `Alexa, stop’ — something like `ok’, or `enough’, or pretty much anything that I mutter […] It’s like talking to someone who just goes on and on, and you’re waiting to find a pause so you can somehow stop them.”

But even some of the correct assistant responses were too wordy. One user complained that, when she tried to add items to the grocery list, Alexa confirmed “<item> added to grocery list” after each one. It felt as too many words for such a repetitive task. Another user called Google Assistant “too chatty” when it provided extra information to a query about pharmacy opening hours. A participant rolled her eyes when Alexa read a long description for each recipe in a list of tiramisu recipes, including a mention of (some) fairly obvious and repetitive ingredients — like eggs.

Voice vs. Screen Results

One of the major uses of intelligent assistants is hands-free usage in the car, in the kitchen, or in other similar situations. Our users considered a vocal answer superior to on-screen answers in the vast majority of the cases. (Exceptions included situations where the answer contained sensitive information — for instance, one woman resented having her doctor appointment read out loud, saying “I would rather have it say the word ‘event’”.)

Most smart speakers don’t have a screen, so they must convey answers in vocal format. This restriction made some participants prefer the speakers over their phone-based counterparts, where a mixed-modal interaction felt more tedious.

Phone-based assistants usually deferred to search results when they didn’t have a ready answer, forcing users to interact with the screen. People were disappointed when they had to use their eyes and fingers to browse through a list of results. They commented that “it didn’t give me the right answer. It gave me an article and links. It doesn’t tell me what I asked,” and “I kind of wish that it didn’t show me just some links… [At least it] should tell me something… And then, maybe `if you want more, check this or that.’”

When the right answer was read, “it felt like magic.” A participants asked Google Assistant “How many days should I spend in Prague?”, and the response came loud and clear: “According to Quora, you should ideally spend 3-4 days in Prague […].” The user said, “That’s what I was looking for in the others; it read the information out loud to me and it also showed the information.” These types of experiences were considered the most helpful by our participants, but they were rare in our study: even though this task was performed by several participants, only one used the “right” query formulation that produced a clear verbal answer; the other six who tried variants of the same question (“OK Google, what do you think would be a good amount of time to vacation in Prague”, “OK Google, how long should I vacation in Prague”, “Hey Siri, how many days is enough for visiting Prague,” “OK Google, what’s a good amount of time to stay in Prague,” “Siri, how many days should I go to Prague for?”, “Siri, if I go to Prague, how long should I go?”) got a set of links instead from both Siri and Google Assistant, except for the last query, which was offered the traffic around Prague.

With Siri, there was another reason for which links were disruptive: those who clicked on a link in the result list were taken to the browser or to a different app, and some did not know how to get back to the list to continue inspecting other results. One iPhone user clicked on a restaurant to see it on a map, and then tried to return to the other restaurants; she said, “Oh no, [the restaurants] disappeared… That’s one thing that bothers me, that I don’t know how to retrieve the Siri request, you know, once it says there’s something you might find interesting … like if I’m driving, if I really want to find who starred in this movie, I could say `add it to my to-do list to do later’ or I could say `look it up’, but I am not going to look at it until I get to my destination, and, by the time I’m there, it’s disappeared… So this list of restaurants is gone because I touched on Maps, so I’ll have to try it again.” (The list of restaurants could have been retrieved should the user have clicked on the back-to-app iPhone button in the top left corner of the screen, but that button was tiny and many users are not familiar with it. However, the more general point of being unable to retrieve the history of interactions is definitely a weakness of Siri compared with other intelligent assistants. Even Alexa allows users to see a history of their queries in the Alexa mobile app.)

Screen-based assistants that transcribed the user’s query caused issues when the transcription was not instantaneous. One participant thought that, because she did not see any of her spoken words on the screen, Siri hadn’t heard her, so she would repeat those first few words more than once. The resulting utterance was usually not properly understood by the assistant.

Partial Answers

Sometimes Alexa openly recognized that it did not have an answer. When it did offer information that was still relevant, although not a direct response to the user’s query, participants were pleased. For example, one user asked about rent in Willow Glenn (a neighborhood in San Jose, California) and Alexa said that it did not know the answer, but offered instead the average rent in the San Francisco Bay Area. The user was pleased that the assistant had recognized Willow Glenn as part of the Bay Area and was okay with the answer. Another user asked “Alexa, how much is a one-bedroom apartment in Mountain View?” and, when the assistant answered “Sorry, I don’t know that one. For now I am able to look up phone numbers, hours, and addresses.”, the user commented “Thank you. That’s really helpful — like ‘Ok, I cannot do that, but I can do this’…”

When, instead of a vocal answer, Siri or Google Assistant provided a set of on-screen results, the first reaction was disappointment, as mentioned above. However, if the results on the screen were relevant to their query, people sometimes felt that the experience was acceptable or even good. (This perception may be specific to the laboratory setting, where participants’ hands were free and they could interact with their device.) Many felt that they knew how to search and pick out relevant results from the SERP better than an assistant (and especially better than Siri), so when the assistant returned just the search results, some said that they would have to redo the searches anyhow. A few people tried to formulate search queries out loud when talking to the assistant and bet on the idea that the first few results would be good enough. These people used the assistant (Google Assistant usually) as a vocal interface to a search engine.

Trust in Results

People knew that intelligent assistants are imperfect. So, even when the assistant provided an answer, they sometimes doubted that the answer is right – not knowing if the query was correctly understood in its entirety, or the assistant only matched part of it. As one user put it, “I don’t trust that Siri will give me an answer that is good for me.”

For example, when asked for a recipe, Alexa provided a “top recipe” with the option for more. But it gave no information about what “top” meant and how the recipes were selected and ordered. Were these highly rated recipes? Recipes published by a reputed blog or cooking website? People had to trust the selections and ordering that Alexa made for them, without any supporting evidence in the form of ratings or number of reviews. Especially with Alexa, where users could not see the results and just listened to a list, the issue of how the list was assembled was important to several users.

However, even phone-based assistants elicited trust issues, even though they could use the screen for supporting evidence. For example, in one of the tasks, users asked Siri to find restaurants along the way to Moss Beach. Siri did return a list of restaurants with corresponding Yelp ratings (seemingly having answered the query), but there was no map to show that the restaurants did indeed satisfy the criterion specified by the user. Accessing the map with all the restaurants was also tedious: one had to pick a restaurant and click on its map; that map showed all the restaurants selected by Siri.

Siri did not show the list of restaurants on a map. To access the map, users had to select a restaurant and show it on a map. Once they did so, some users did not know how to recover the list of restaurants (which could be done by clicking the back-to-app button Siri in the top left corner of the screen).