#vicomte de ségur

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I finished watching Franklin the other day and I had to comment on the portrayal of La Fayette throughout the series – while there were some things that I disliked, the show did a really good job portraying La Fayette. I have a lot of notes and screenshots because the show actually included a great number of sweet details. Therefore, I hope you are interested, because we are going into detail.

Franklin – Episode 1

There are two important things happening in this episode with regards to La Fayette: La Fayette’s first meeting with William Temple Franklin and their visit to the club.

The show naturally puts the two Franklins at the center of all the action and this is – with regards to La Fayette, one of the “problems” it suffers from. La Fayette’s departure for America and the whole politics behind it are oversimplified, the show omits his visit to his uncle-in-law in England and its also omits Silas Dean. Dean played a very important role in getting La Fayette to America – arguably more important than Franklin’s role and definitely more important than Temple’s role. La Fayette and Temple knew each other, they exchanged letters and these letters were polite and friendly, but there are none of these overenthusiastic declarations of love that we see in letters to his family, to Adrienne, to Washington or Hamilton for example. In fact, the first letter I could find between the two of them was written by La Fayette on September 14, 1779 – so long after La Fayette’s initial departure. As I already said, the letter is friendly, but not overly so. There might be other letters, that did not survive and many things could have happened, that can not be represented by letters and what is written in them – but I nevertheless think it is safe to assume that the show depicts a deeper friendship between them then there actually was.

With that out of the way, we meet La Fayette for the first time in de Vergenne’s anteroom where Temple is also currently waiting for an audience. When I was watching the show, especially in later episodes, I am not quite sure if it was made clear, that de Vergennes and La Fayette actually had a very warm relationship. Sure, de Vergennes sometimes needed to reign La Fayette in a bit but they were still very affectionate with each other. I saw their interaction in the show always as a mentor-son-thing or some friendly banter but I am not quite sure if you got the same impression when you have not read their letters for example.

Anyway, the real star of this scene was La Fayette’s uniform. This set probably won me over to watch Franklin – because the show actually managed to put La Fayette in the right uniform at the right time!

Here he is wearing the uniform of a Captain from the Noailles regiment. He joined the regiment in 1775 and his commission was a “wedding-gift” from his father-in-law who owned said regiment (although La Fayette had to wait until he turned eighteen to actually be commissioned a Captain). La Fayette wore this uniform in a painting by Louis-Léopold Boilly – although the painting was only done in 1788.

And of course, there was no way the show could do without a scene about La Fayette’s many first names.

I was baptized like a Spaniard. (…) But it was not my fault. And without pretending to deny myself the protection of Marie, Pauls, Joseph, Roch and Yves, I more often called upon Saint Gilbert.

Then we have this absolutely delicious scene of La Fayette dressing Temple up – something very much on brand. @my-deer-friend and I once had a conversation about La Fayette doing something along these lines with John Laurens as well if I am not mistaken.

Next we are taken to a club where La Fayette introduces Temple to his friend Ségur and de Noailles – I really liked it that they were included as well:

And in the course of the conversation there were many interesting aspects raised. For example, there is a reference to La Fayette’s “country-origins”, something that was perceived by his peers back then as way more significant, to the point where he was ridiculed for it, then we today might believe it to be. There was also a spotlight shown on La Fayette’s pursuit for glory and fame, a strong factor in the crafting in his public image and something that was very important for him. I made a post about this here.

We also have La Fayette express his distaste for the British and relay the story about his father’s death. And while I appreciate the background information and motivation, I think that “We hate British” is a bit of an oversimplification – as I said, La Fayette had recently visited his uncle by marriage in England, he was the French ambassador to the British court, and by his own accounts, La Fayette had a blast of a time while in England. I also would like to one day look a bit deeper into the connection La Fayette felt towards his father and his passing, because I believe that he might not have felt quite so strong about the matter.

Lastly, La Fayette comments about his distaste for court rituals. While this was his general opinion, there was one especially notable incident were he purposefully insulted the future Louis XVIII, younger brother of Louis XVI, in order to avoid an appointment to the royal household. I wrote about his little stunt here. He also mentioned that the King at the time, Louis XVI, had forbidden him to sail to America. The logical conclusion: La Fayette bought his own ship.

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#lafayette#french history#american history#american revolution#history#franklin tv#episode 1#benjamin franklin#william temple franklin#comte de vergennes#tv series#1779#louis xvi#louis xviii#come de ségur#vicomte de noailles#théodore pellerin#really good casting

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello!! Do you know much about when Lafayette fled Versailles?

The Marquis de Lafayette, the Vicomte de Noailles, and their friend the Comte de Ségur plot together to find a way to join the American cause. All three are minors and have to ask for permission from their parents to join. Ségur quickly gives up the idea and moves on. The Vicomte asks his and, respectively, Lafayette’s father-in-law if they can go. He gives them the big N-O.

Through some dealing by the sneaky Comte de Broglie, the Vicomte and Lafayette meet Johann de Kalb…the ‘baron’…and tell him that their father-in-law is totally cool with them going IF they can be officers. They want to meet Silas Deane–the guy responsible for shipping off Frenchman to America faster than you can say STOP. De Kalb agrees.

Lafayette meets Deane, who wasn’t too keen on dropping everything to help a 19-year-old who wanted to be a big baddy in the war against the English. Lafayette fibbed again, saying his family wouldn’t let him go without the rank of general–and that he was cool with not getting paid. Deane loved the idea of Lafayette not having to get paid and wrote up a contract. At the same time, the Duc d’Ayen tries to get official permission from the court for the Vicomte to go. They shoot the idea down and the Vicomte is out.

Lafayette scrambles around for someone to give him permission to go with no success. In essence, no one is signing his release form so he can go on the field trip. The French court cracks down on officers leaving for America. DeKalb, who had tried to sail and had been sent back to Paris, is now waiting to leave as well. He and a few others decide to convince their rich young buddy to pay for a ship so they can get the heck out of France.

In an odd turn of events, Lafayette’s family arrange for him to go to England where he was very bored and met General Clinton at the opera…who had just returned from doing a number on Long Island, George Germain, and King George III. The young marquis gets word that DeKalb is about to sail without him and he promptly fakes being sick so he can skip a meeting with the British court, sneak out of England, and–unbeknownst to him–dodge two English spies who had a good idea of where he was headed.

Back in France, Lafayette takes the time to gloat to the two drop-outs, Ségur and the Vicomte, that he’s sneaking out of France. He writes a Dear Fam, I’m Going To America letter and rushes off to meet DeKalb. The Noailles get the news and–minus Adrienne and her mama–are outraged. Ségur thought all of their ire was very funny.

Just when Laf and company are ready to sail, a messenger arrives saying his folks told the king on him. If he doesn’t go back home, he’s likely to receive a lettre de cachet…a royal imprisonment order. Lafayette throws caution to the wind and starts sailing…only to essentially panic and turn back around.

A series of bumbling back and forth messengers start showing up from nobles trying to help or dissuade him. Eventually, sneaky Broglie (who had his own reasons for wanting Laf in America) sends a messenger with the lie that the mess has all been a big show to make the Noailles feel better and that he can leave for America any time he wants. Lafayette, finally getting someone’s permission, sets sail from the Spanish coast-line and heads for America.

#Marquis de Lafayette#Anonymous#Lafayette#Comte de Ségur#Vicomte de Noailles#Duc d'Ayen#Duchess d'Ayen#Adrienne de Noailles#Johann de Kalb#Comte de Broglie#Silas Deane#King George III#George Germain#Henry Clinton

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Empress Eugenie surrounded by her ladies in waiting, painted by Franz Xaver Winterhalter and completed in 1855.

Anne d'Essling (1802-1887) served as Grand-Maitresse for Empress Eugenie from 1853-1870.

Next to the Empress Eugenie is her dame d'honneur, Pauline de Bassano. Born in 1814, she served this position from 1853 to her death in 1867.

Jane Thorne(in white dress with blue ribbon) was born in New York in 1821 to American millionaire Herman Thorne and Jane Mary Jauncey. She kept her position to Empress Eugenie from 1853 to 1870. Her husband, Eugène Stéphane de Pierres was the equerry to the Empress, he kept his position for the same amount of time as his wife.

Louise Poitelon du Tarde(next to Jane Thorne)was the daughter of Louis Gabriel Poitelon du Tarde and Louise Anne Vétillart du Ribert. Born in 1826, she became Dame du Palais for Empress Eugenie after the Empress' marriage to Napoleon the third. By 1864 she was declared an invalid and was requested to leave her position, but remained an honorary lady in waiting.

Anne Mortier de Trévise(in purple) was born in 1829 to Napoléon Mortier, II. duc de Trévise and Anne-Marie Lecomte-Stuart. Anne was often the traveling companion to Empress Eugenie. Her parents died before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war, followed by her son, who died in battle and her daughter who died in childbirth. Her husband suffered a deep depression due to this and Anne devoted herself to nursing him.

Claire Emilie MacDonnel(in white, with roses on her dress)was the daughter of Hugh MacDonnel and Ida Louise Ulrich. She married marquis de Las Marismas de Guadalquivir, in 1841. After his death in a mental asylum, she married her brother in law Onésipe Aguado, vicomte Aguado, in 1863. After the fall of the Empire, she retired from high society life as her loyalty to the Empress Eugenie made her feel disloyal if she were to participate in society life under the new administration.

Nathalie de Ségur(in yellow) was born in 1827, she accompanied her husband on his diplomatic missions as he was the minister to Florence and because of this never attended court very often.

Adrienne de Villeneuve-Bargemont was born in 1826, she was the daughter of Alban Jean-Paul de Villeneuve-Bargemont and Emma de Carbonnel de Canisy. Her son often joined her in court at the request of the Empress, the boy composed poems for Eugenie and read them to her. The Empress was particularly attached to Adrienne and mourned her deeply when Adrienne died on June 7th 1870 after an illness that had affected her for several years.

#french history#jane thorne#adrienne de villeneuve-bargemont#nathalie de ségur#empress Eugenie#anne d'Essling#claire emilie macdonnel#pauline de bassano#louise poitelon du tarde

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have a question! I’ve seen on here that Adrienne is apparently Lafayettes cousin? Is that true? I’ve been struggling to find a source for that…some help would be great! 😭❤️

Dear Anon,

That is a very interesting question; the short answer is no, the longer answer is probably. Allow me to elaborate:

Pedigree and one’s heritage was very important for the aristocracy of the 18th century in French. Part of the reason why La Fayette was considered as such a good match for Adrienne was his family name. If we have a look at this family tree, we see that Adrienne and La Fayette were not directly related, they were not first cousins.

La Fayette’s mother was an only child (I believe her father was as well?) and his father had two sisters, one never married and the other one married, had a daughter and was widowed young. That daughter and La Fayette had a very close relationship, and she was like a sister to him. She died in childbed while he served in America, and he deeply regretted not being able to see her again before her death.

That was the short answer, as to the longer answer; cousins are not all created equal. While we established that Adrienne and La Fayette were not first cousins, they could still be cousins of a different degree. The books and research I have read so far are not particular detailed when it comes to the extended family on both sides and I have never done too much research on my own into the ancestry of the de Noailles family – I am with John Adams on this point, the family tree of the de Noailles is just too convoluted and too interconnected.

But here is where it gets tricky. La Fayette was most likely a cousin to his father-in-law (in some shape or form). In her book, Laura Auricchio calls La Fayette the duc d’Ayens “cousin-turned-son-in-law”.

The Duc d’Ayen also had a cousin (the oldest son of his father’s younger brother), Louis Marie de Noailles, Vicomte de Noailles. Louis was also a cousin of La Fayette’s (again, please do not ask me how exactly they were related). But more so, he was also La Fayette’s brother-in-law for Louis married Louise, the older sister of La Fayette wife Adrienne.

Now, to top it all off, Louis and La Fayette both had a close friend, Louis-Phillipe, comte de Ségur. He married Antoinette Élisabeth d'Aguesseau. Antoinette was the younger sister of Adrienne’s and Louise’s mother – Ségur was therefore technically his two best friends’ uncle by marriage.

As you can see, there is a lot going on and there certainly was some sort of familial connection between the de La Fayette’s and the de Noailles���, but it was not a very close one for all that I know (and I am quite firm in the families history for three to four generations). But chances are high that I will take a deep dive into the French archives next year and might look more detailed into the de Noailles family.

Until such time, (or until someone else has more information about the topic) I hope this answer could clear some things up and that you have/had a wonderful day!

#ask me anything#anon#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#lafayette#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#french history#american history#history#louis marie de noailles#louis phillipe comte de ségur

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello dear,

I have a question that I hope isn’t too off topic or has already been asked.

I am currently reading through Adrienne de Lafayette’s bio by André Maurois and he keeps referencing the Marquis’ friend Ségur. I recall this name from other Lafayette biographies I have read but there I encountered the same problem. Does he have a title or a first name? It appears his father was a well respected general? But I can’t seem to piece together who that family is or what their standing was. I would love to know more about him, maybe dig into some correspondence as that is my one true vice. 😆 I just thought I would ask the Oracle since I’m stumped. 🤓😁

Well my dear @aconflagrationofmyown, I think I can help you with that. :-)

Yes, this mysterious Ségur has a name and a title. The “Ségur in question” was Louis Phlippe, comte de Ségur, born on December 10, 1753 in Paris and died on August 27, 1830 in Paris. He published his Memoirs and they are really worthwhile to read - interesting stories about a young La Fayette, insights into the inner circles of the French court at the time and of course into Ségur’s personal life. Here is his description of his relationship with La Fayette:

The three Frenchmen, distinguished by their rank at court, who first offered their military services to the Americans , were the Marquis de La Fayette, the Viscount de Noailles, and myself. We had long been intimate friends, and our connexion, which was strengthened by a great conformity of opinions, was soon after confirmed by the ties of blood.: La Fayette and the Viscount de Noailles had married two daughters of the Duke de Noailles, then bearing the title of Duke d'Ayen; their mother, the Dutchess d’Ayen, was the daughter, by his first marriage, of M. d'Aguesseau, Counsellor of State; and son of the Chancellor of that name M. d'Agur esseau had, by a second wife, twenty years after, several children, one of whom was M. d'Aguesseau, now a peer of France, a daughter, married to M. de Saron, first President of the Parliament of Paris, and another daughter, to whom I was united in the spring of 1777; so that, by this alliance, I became the uncle of my two friends.

Comte de Ségur, Memoirs and Recollections of the Count Segur, Ambassador from France to the Courts of Russia and Prussia, &c. &c., Wells and Lilly, Boston, 1825, p. 84.

Ségur’s descriptions of family relations is as confusing as it could possibly be and therefor once more in simple terms. La Fayette’s wife Adrienne had an aunt, her mother’s younger sister Antoinette-Elizabeth-Marie d’Aguesseau. This sister married Louis Philippe, comte de Ségur in 1777 in Paris and the couple had four children, three sons and one daughter. Ségur therefor was La Fayette’s uncle by marriage. Here is an example of how La Fayette described Ségur and their relationship. He wrote to George Washington on April 12, 1782:

This letter, My Dear General, Is Intrusted to Count de Segur, the Eldest Son of the Marquis de Segur Minister of State and of the War Departement Which in France Has a Great Importance—Count de Segur Was Soon Going to Have a Regiment, But He Prefers Serving in America, and Under Your orders—He is one of the Most Amiable, Sensible, and Good Natured Men I Ever Saw—He is My Very Intimate friend—I Recommend Him to You, My dear General, and through You to Every Body in America Particularly in the Army.

“To George Washington from Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, 12 April 1782,” Founders Online, National Archives, [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of George Washington. It is not an authoritative final version.] (05/20/2022)

You said you have already done some digging on your own and I assume you came across Ségur’s Memoirs. I include some links just in case and for everybody else who might be interested. Ségur’s memoirs are normally split into three volumes.

Internet Archive, French original: Volume One - Volume Two - Volume Three

Internet Archive, English Translation: Volume One (they do not have any more volumes in English)

Google Books, English Translation: Volume One - Volume Two - Volume Three

Since Ségur also worked as a diplomat and historian, he authored quite a number of works. Here is a little overview of all of his freely accessible books at the Internet Archive and via Google Books.

His second-oldest son, Phillipe-Paul also wrote his memoirs: An aide-de-camp of Napoleon. Memoirs of General Count de Ségur, of the French academy, 1800-1812.

Ségur hailed from a very well situated family. His father was Philippe Henri, Marquis de Ségur, decorated general and later Secretary of State for War during the American Revolution. He was the grand-son of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, regent of the Kingdome of France, by Orléans’ illegitimate daughter Philippe Angélique de Froissy. Ségur also had a younger brother, Joseph Alexandre Pierre, vicomte de Ségur. It is rumoured that Joseph Alexandre Pierre was not the son of Phillippe Henri but had actually been fathered by his “fathers” friend, Pierre Victor, baron de Besenval de Brünstatt. To my knowledge that had never been officially proven though.

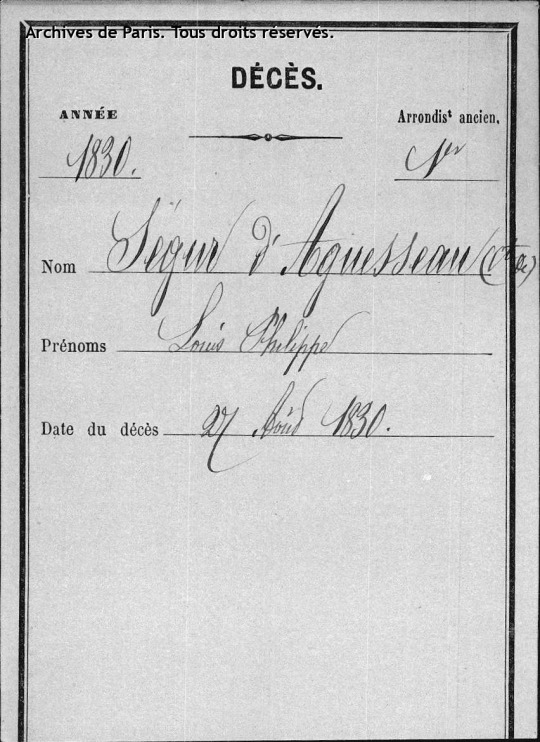

The État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859) should technically have Ségur’s Acte de Décès but I could not find it at first glance. I did find however the corresponding Fichier in the État civil reconstitué and maybe that is of interest for you as well. It is quite interesting to observe that Ségur’s last name is given as a combination of his and his wife’s name.

Paris Archives, Fichiers de l'état civil reconstitué, Cote V3E/D 1356, p. 21. (05/20/2022)

You also mentioned that you were interested in correspondences - in fact, you said that they are your one true vice and I can absolutely understand that. Under the cut (as not to bother everybody who is just casually scrolling) I include the one fully transcribed letter by Ségur that I have. There are also a couple of letters where I only have the dates and short summaries - just let me know if you are interested in them as well.

I hope you have/had a beautiful day!

The comte de Ségur to the Marquis de La Fayette

Rochefort, July 7, 1782

I received, my dear Lafayette, your friendly letter, and I was extremely touched. I love you madly and I cannot console myself that I am not traveling with you. You are going to play a very honorable role, and one that is very difficult to play. You will have to reconcile the French and American characters, deal tactfully with opposing interests, and fill the measure of your glory to overflowing by adding the olive branch to the laurel leaves. And you will even have to act against your own inclination by helping to put a definite end to the horrible scourge to which you owe your fame. I am very sorry not to be able to talk with you freely at the moment I most desire it. But letters are not safe enough, and I haven't anything to tell you but things I would not want to be read. I foresee that you are going to be more revolted than ever at English arrogance, stupid Spanish vanity, French inconsistency, and despotic ignorance. You will see that the cabinet tries one's patience as much as a battlefield, and that as many stupid things are done in a negotiation as in a campaign. You will see especially how essentials are sacrificed to form, and you will say more than once, “If chance had not made me one of the principal actors, I should certainly not stay in the theater.” But the more obstacles you encounter, the more merit you will gain. How could you not succeed in all you desire, for you have genius and good fortune. To have that is to have half again as much as it takes to be a great man. Farewell, my friend. I expect to leave the day after tomorrow, consoling myself rather philosophically for going two thousand leagues for nothing, but not consoling myself for not finding you in a place that I find full of your name and your deeds. I shall carry out all your commissions, and I shall point out the patriotic sacrifice you are making in temporarily exchanging your sword for a pen. I request that you love my wife, hug my children, take my place with my father, and join us as soon as you can to sound the charge or beat the farewell retreat.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 5, January 4, 1782‑December 29, 1785, Cornell University Press, 1981, p. 51.

#ask me anything#aconflagrationofmyown#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#american revolution#french revolution#history#letter#george washington#comte de ségur#marquis de ségur#vicomte de ségur#1753#1777#1730#1782

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Fayette and his “rascal” friends

To the Prince de Poix, May 4, 1780:

When you find one of those rascal friends of mine, those disreputable and welcome young men Ségur, the Vicomte de Ségur, Etienne, Puységur, our brother, Charlus, and Damas, embrace each of them ten times for me, and tell them not to forget their friend Lafayette.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 3, April 27, 1780–March 29, 1781, Cornell University Press, 1980, p. 6-8.

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#american history#american revolution#french history#letter#history#1780#prince de poix#friendship

18 notes

·

View notes