#vet was baffled by it and did her research and it seems like as long as he doesn’t do it awake it isn’t neurological

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“grumpy boy” as the tech called him got the diagnosis from the vet of “weird but not a crime”. they all loved him and said he is very handsome

we were told though he is an absolutely perfect health 🧡

#he does this weird shivering thing when he sleeps sometimes#only when he sleeps and it isn’t even all the time#wake him up and he stops#vet was baffled by it and did her research and it seems like as long as he doesn’t do it awake it isn’t neurological#but she wants videos for more research lmao#i love this little brat#santiago#cat#kitten

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your Kiss is on Their List Pt 5: Yang Xiao Long

This was familiar. This mental soup of lingering ecstacy and satisfactory subordination, she hadn’t always known it, but it was normal for her now. It wasn’t overly often that this would happen, all parties involved had things to do of course, but it was common enough that there was a sequence of events she was used to going through. As were they.

First, she would go to the club, that fateful club where she had made an impressive, if a bit unnecessary, show of force on the establishment’s security detail and owner in lieu of getting the information she needed. There, she would do some drinking, maybe a bit of dancing, or even, more recently, shoot some pool in that newly renovated nook beside the bar. Nothing out of the ordinary, nothing one couldn’t find in most other nightclubs in cities like Vale. Great music though.

Then, the odd dance would begin. They would approach her, those bedeviling women, and they would flirt like they’d only met once or twice before and hit it off. They’d give her an opening line, she’d shoot something charming back and they’d go back and forth like that for a while. Then they’d invite her to the back, she’d push through the cool rush in her chest and say yes at an appropriate volume. They’d then escort her to the back, and she would positively relish the jealous looks she’d get from charmless men. Very few got the honor of meeting up with the twins in private regularly, save for Yang Xiao Long and one other.

Then they’d lead her to their room, lavishly furbished with leather furniture, modern art, and the most well-stuffed bed she’d ever been on. It was always just a little chilly in there; not cold enough for an additional layer, but you’d always be doing the little things to warm up ever so slightly. Things like crossing your arms, or being close to someone else. Part of their setup, no doubt. There, one of them would sit her on the couch and heap compliments on her while the other sat on an adjacent chair and methodically apply vibrant red lipstick. She’d catch her staring, she’d always catch her staring, and the other would know exactly when to stop talking and redden her own lips as Yang was caught in a suggestive gaze. They were frighteningly good at what they did.

Then, with gentle tugs, they’d pull her from the couch to the bed and begin the main event. They’d lean on either side of her and start with her cheeks. Gentle, lingering kisses that let her relish in the contact and warmth. They’d refresh the kiss-shaped stamp they had on her brain. They would work their way to her nose, and her forehead, and her temples, and her jaw, and her neck. Then they’d help her remove her jacket and scarf, she’d often already in a trance at that point. With only her tube top remaining on her torso, they’d kiss her neck, then her shoulders, then they’d let her slowly fall to the bed as they worked their way down her arms and to her hands.

At that point, they would ask her the question; how far would they go tonight? Yang would have to tell them, with a please. They never demanded one, never even asked for one, but she’d always say please. They’d always oblige her, if she asked for a full coat, they paint her red from head to toe. Sometimes, when she was in the mood, she’d ask for something along the lines of “the full package,” and they’d oblige her.

Finally, they’d be done, and she’d be speechless. It had been a long time since the first occurrence of this, but she would always be speechless, staring at the ceiling, and simply plastered in impressions of lips, residue of blissful kisses that would put her firmly on cloud nine, regardless of whether or not her pants stayed on. They’d leave to the adjoining bathroom and clean themselves up.

Recently, if they hadn’t gone all that far, another step would occasionally come up. She would, without cleaning herself up, pick herself off the bed and wobble her way to the bar. She would be too love-drunk to care about the bewildered stares she’d get from the jealous and the envious, and order herself a lite beer, or even a water. Something simple to revitalize her system. There, she’d be joined by the only one to be able to truly sympathize with her, the only one who could claim to be in her shoes more often than Yang herself.

Tonight was one of those nights, and Cody Baxter was that individual.

Cody was, in many ways, Yang’s polar opposite. A passive pacifist who never looked to instigate anything aside from chill vibes. He was a writer by trade, and wouldn’t consider himself charming. Which made it as baffling to him as it was to many others when the infamously seductive Malachite Twins rented out a space in the club for the guy and showered him with affection whenever they got the chance. The only one more often covered in lipstick from the twins than Yang was Cody.

Though tonight, he was clean and Yang was the recent target.

“Y’know,” he started “,we gotta stop meeting like this.”

“What,” she shot back, words slightly slurred “,you think you could hold up any better?”

They both chuckled like old war veterans, warmly recalling what others would consider nightmares.

“I take it this was your way of getting a ‘lightened sentence’ as it were?” he asked with a glance at the blonde.

“Yyyyyyou could say that I guess.” She took a swig of beer. “If what they did to my team was their version of going easy, I’d rather this,” she gestured to her marked self “,than whatever they were planning for an old vet like me.”

“Y’know, you say that,” he said, melancholy slowly entering his voice “,but I don’t think either of us handle them better now than when we got got for the first time.”

“Oum, the first time...”

-----------------------------

That club was so nice on her first visit, and cleaned up so nice the second, why not go again just for fun?

She was owed a drink, after all. Yang strutted into the club, the music was back, the patrons were back, and Junior was back. Back, too, were those twins who she never got to be properly introduced to.

With strawberry sunrise in hand, Yang took a seat between them at the bar. This place was worth being a regular at, best to ingratiate herself with the staff, especially the boss’s right hand girls.

But there was two of them so... right and left hand? Anyway.

“W’hey there!” she opened “So, I’m not so great at apologies, so how about I just buy you ladies a round?”

The two haughty women rolled their eyes and nodded in acquiescence.

Yang signaled to the bartender who promptly slid some fancy drinks to the twins, their favorites, Yang presumed.

“So, dunno if you’re cool enough with me for this, but would you mind if I got your names?”

A heavy pause followed.

“Melanie.”

“Miltiades.”

Yang was thoroughly surprised. She would’ve bet her bike that, no, they were not cool enough with her yet. Might as well strengthen her advantage then.

“Well, I gotta say, Melanie, Miltiades,” holy shit, did she just nail the red one’s name on the first try? “you girls are pretty damn good fighters.

Apparently, the praise was enough for the twins to deign her with their gazes instead of cold shoulders.

“I mean, most people have to fall back on their semblances when I go on the attack, but you two? Correct me if I’m wrong, but you guys didn’t even raise your aura when I hit you, did you?”

Another heavy silence.

“Knowledge is power,” Melanie said plainly.

“Uhhh... huh?”

“If we used our semblance for every punk with their head in their ass,” Miltiades clarified “,people could scout us for planned attacks.”

“Not that you’d know anything about that.” They scoffed in unison.

Ouch.

“W-well,” Yang tried to get back on balance “,I’ll be the first to tell you, I have a lot of muscles that might be the strongest,” she flexed her arms to drive the point home “,but my brain ain’t in the running!”

Self-deprecating humor, she didn’t use it often, but this seemed like a good time to bust it out. Some humility never hurt when trying to earn some forgiveness, right?

*chu*

Yang felt what happened, heard what happened, but her brain needed some time to process it. she looked to each of her biceps and found a red lipstick-imprint on each of them and a twin caressing an arm each.

Yang’s face lit up like a traffic light, but no words came out. Noises escaped her mouth for sure, but they were most definitely not words.

“You know, for as hot-headed as you are,” Melanie said, pausing to kiss Yang’s forearm “,you definitely have a charm about you.”

More noises, no words.

A soft hand cupped her cheek and turned her toward its owner; Miltiades, who had closed the distance and was inches away from her face.

“Y’know, you’re so cute, we can’t stay mad at you. How about we get away from the crowds so we can... get to know you better?”

There was a heavy silence.

Without taking her eyes off Miltiades, Yang picked up her strawberry sunrise, downed it in one go and croaked out “Sure.”

------------------------------

“Well if it isn’t our two favorite patrons!”

Melanie’s peppy arrival snapped Yang out of her recollection.

“Heyo, Mel,” Cody greeted the twin “,to what do we owe the honor?”

“Just a quick bit of correspondence we would like our blonde friend to deliver.”

Curious, Yang turned to the pair fully to find Miltiades holding out a business card. She took it, read it, and her eyes widened.

“Uhh... girls?” she said with trepidation in her voice “,I don’t wanna tell you how to go about your business, but this... this might not be the best idea.”

“Yang, for real, we appreciate the concern,” Miltiades said with uncharacteristic bluntness given their recent escapades “,but we’ve done our research. Trust us, we’ve planned this one out thoroughly. We know what we’re doing.”

“If you say so.” Yang looked down at the lipstick-stained card. “Better brace yourself, vomit-boy.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snippet of Kacchako Day 0 Story: “Breathe For Me”

(I didn’t know Kacchako Week was a Thing until like two days ago so this is horribly rushed but I regret nothing)

There had never been a moment where Ochako was more thrilled than the moment she opened the letter and found out that she had actually won the scholarship. She had worked her soul into the ground for it, prayed and spent sleepless nights over it, but she had never actually expected to get in. Not to U.A., the most prestigious school for all aspiring oceanic explorers and aquatic vets and anything that had to do with anything under the waves. There were so many other applicants with more money, more connections, more prior training when all Ochako had was a passion for helping and an all-consuming love of the ocean. Or, more specifically, the mysterious humanoid race that lurked within it.

Humanity had known about merfolk and visa versa for centuries, even if most of humanity had passed the knowledge off as legends and wives tales for much of that time. But solid, undeniable contact had been made eighty years before Ochako was born, with the first merman being accidentally caught in a deep sea trawling expedition. The merman had been let go by the surprisingly moral fishermen after some pictures and excited recordings, but after that, everyone had been on fire over the realization that there really was another species similar —or equal— to humans in intelligence and power.

Because merfolk were intelligent. Dangerously so. They did not speak any known human language and their behavior could be very primal compared to modern sensibilities, but a few cautious contacts and tests revealed that they could learn any writing system and understand any language presented to them. Not just simple words or phrases like apes or cats or other animals, but true language. Written communication or fluent sign language and an ability to comprehend even the most complicated sciences.

The history books, of course, focused on the brief but brutal flares of conflict that had started and died out over the eighty years after formal contact was made. Mostly between humans who wanted to exploit the “creatures of myth” or merfolk who took offense to the submarines that wandered too close to their ancestral territories. But while humanity had technology on their side, the merfolk had magic and an entire ocean with which to wield it and neither side had wanted war badly enough to risk mutual destruction of land or sea.

By the time Ochako had been born, there were official treaties in place between the two races —if shaky ones—, designated areas and depths where humans were allowed, where humans and merfolk were allowed, and where only merfolk were allowed. Most of merfolk culture was unknown and bizarre —it was hard to interview people who couldn’t speak your language and didn’t really like talking to you anyway—, and while there did appear to be countries below the waves, what country meant to merfolk was … different compared to humans. A lot of things were different to humans, and while merfolk demanded recognition as a free and sentient species, in a lot of ways they didn’t seem to care when humans treated them more like the ocean creatures that they shared a home with.

Case in point, U.A., the school Ochako had always dreamed of going to. It specialized in oceanic exploration and the care of aquatic life, and half the campus was dedicated to a rehab center for a mind-boggling variety of ocean creatures who had been injured in fights, or in illegal poaching, of any number of things. Students of U.A. not only got to learn from the best minds and most experienced professionals of their dream job, but they frequently got to work with creatures from every ocean there was.

Including merfolk.

U.A. was one of only two known human-run establishments that served as the home of a merfolk pod. U.A.’s pod mostly consisted of mermen and mermaids who had been injured at sea and couldn’t really stay out in the open currents —such as the now famous Toshinori, who had badly injured himself saving an ocean liner of humans—, or just those who, for whatever reason, liked humanity rather than only tolerated them. It was one of only two pods that had regular, friendly contact with humans. Researchers and anthropologist all over the world paid fortunes for the privilege of seeing either pod, but for U.A. students, the honor of meeting and interacting with merfolk didn’t cost fortunes, all it cost was school tuition and impressively good grades.

Or a once in a lifetime scholarship offer for those specifically looking to train in merfolk care and culture like Ochako.

Who had actually won the thing and spent the next weeks leading up to moving into the U.A. dorms losing her mind with joy and nerves combined.

First day in class their teacher, a boisterously loud culture and music specialist called Yamada Hizashi welcomed them to U.A., lectured them on the basic dos and don’ts of interacting with merfolk and then hauled them all down to a different building entirely for their “homeroom class”.

Ochako was baffled as to why their classroom was not in the main school building until Yamada-sensei slammed open the doors to a huge room with a glass wall that only went up halfway, through which Ochako could see a little piece of what had to be a huge underwater aquarium. Laughing at their astonished faces as he herded them to the desks right next to the glass, Yamada-sensei said, “Everybody put your hands up for the other half the class and your other homeroom teacher, yeah?”

Oh. Thought Ochako faintly as she pressed her hands against the glass, that’s why this class is only half-sized. I haven’t met all of them.

She waited breathlessly for someone, anyone, to appear, tried not to bite her lip in anxiety when nothing happened for several minutes. Yamada-sensei sighed after the fifth minute of empty water and, without warning, climbed up the steps to the top of the glass wall, stuck his head underwater, and gave a strange, shrill scream. Pulling his head out of the water and flipping his soaking hair back like everything was perfectly normal, he grinned smugly, “That should do it. Just one more minute and… there he is! Lazy bum.”

Ochako gaped as the bright yellow lump half-hidden in a patch of swaying kelp that she’d assumed was a rock unfurled and darkened to inky black and stoney grey. With graceful, twisting limbs, the man who had been playing stone —sleeping?— a moment ago swam over to the edge of the glass and settled next to Yamada-sensei’s seat on the other side. Yamada-sensei flipped a switch on his desk and said, “Took you long enough, sleepy head.”

The merman flicked a few of his tentacles in a gesture that looked rude, then faced the class with a vaguely dead expression and folded his hands into the sign language for “hello”. While the rest of the class whispered and Yamada-sensei cheerfully introduced the merman as “Aizawa Shōta, just call him Aizawa-sensei”, Ochako stared at him with wide, wondering eyes.

From the waist up, he looked like a very tired human being. Hooded black eyes and swaying black hair, rippling muscles and scars barely hidden by the grey scarf that seemed to be his only clothing. He even had stubble along his jaw like her father when he forgot to shave. From the waist down, however…

Eight black tentacles, each several feet longer than Ochako was tall, fidgeted idly against the floor of the aquarium. His “hips” were not as wide as she would have thought for having so many limbs, but every twitch of his tentacles made his scales ripple faintly from the muscles beneath.

Ochako had studied a lot of ocean life in her childhood, watched every documentary, seen every youtube clip, gone to every aquatic show she could. She knew what suppressed, predatory power looked like, and Aizawa-sensei was it.

The merman sagged quietly against the glass, already ignoring the human students in favor of holding a half-sign language —on his part—, half Japanese —on Yamada-sensei’s part— argument over the entire concept of two homeroom teachers for one class. Or just Aizawa-sensei having a class in general, if Ochako was remembering her sign language lessons correctly.

Yamada-sensei waved his arms, “Just call the rest of the class already so we can get started!”

Aizawa-sensei sighed with an explosion of bubbles, looked over his shoulder and gave a low roll of chirps and clicks Ochako could only hear over the speakers Yamada-sensei had turned on. A few seconds later, the first of their classmates trailed in, each one of them as wondrous and exotic as their new teacher.

Read the rest on Ao3

Read the rest on FF.net

#bnha#bnha au fic#bnha katsuki#bnha ochako#kacchako week 2019#modern merfolk au#quirkless au#bnha class 1a#katsuki x ochako#bakugou x uraraka#Katsuki is a lionfish merman#unbeta'd we die like men#Secret-Engima's Writing#Melodies and Manuscripts

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

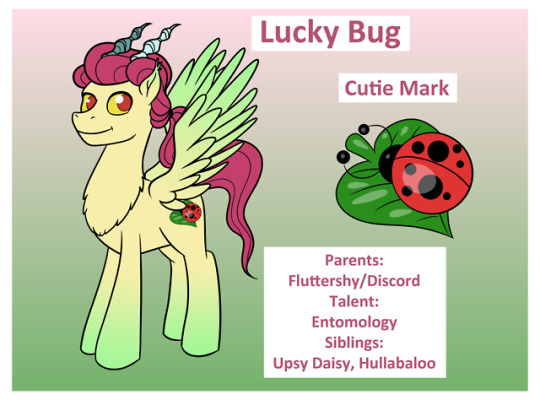

Note: This has been drawn as a reference guide which is free to use if you wish to draw this character. However, please do not repost or claim as your own, thank you.

Finally, more Next Gen! Here's the ninth born and the eldest of The Young Five. Lucky Bug

Personality: Inquisitive, sarcastic, excitable, nervous, smart, easily embarrassed.

Likes: Insects, singing, wild adventures, camping, pretty things (and mares).

Dislikes: Discord’s interest in his love life, his eyes and horns, ponies staring, getting wound up.

Story;

Lucky Bug is the eldest son and second born of Fluttershy and Discord. He is the middle child, younger brother to Upsy Daisy and older brother to Hullabaloo.

Lucky was born out of unusual circumstances. He wasn't conceived inside the womb like Daisy was. In fact, Fluttershy and Discord were very careful not to have any more ‘accidents’ again. However, that was not meant to be. For a long time, Discord kept experiencing terrible stomach aches. According to the doctors, though, he was perfectly healthy. They were completely baffled as to where the source of the pain was coming from. It had gotten so bad that Discord sometimes couldn't get out of bed. Fluttershy tried her best to help her husband but nothing seemed to ease his pain. One day, the family were having breakfast when suddenly, Discord doubled over in pain, twitching and writhing until finally, he fainted. On the chair where he was now sat a large green and red dragon-like egg. Fluttershy, shocked and in a tizzy, rushed to get the vet, doctor and Twilight over while Daisy attended to her exhausted father. Nopony could explain why or how Discord developed an egg and laid it, not even Discord himself.

Nevertheless, once it was revealed that there was a Pegasus embryo inside, the pair made preparations for a new baby, despite their exasperation at another accident and Daisy’s confusion as to where babies actually come from. The egg was placed in an incubator and kept a close eye on for several months.

And in those several months, a lot happened. Eight year old Daisy was kidnapped and tortured for a week and even after she was rescued, she developed bad PTSD and other mental health problems and anxieties that would stay with her for the rest of her life. Starting a day after her rescue, Daisy hid in a kitchen cupboard for a month. She only came out once she realised the egg was beginning to hatch but it was struggling to do so. She helped the egg hatch properly and out popped a wailing green baby pegasus with pink hair. It was only after that did Daisy begin to get better mentally and went outside to see her friends. Baby Lucky didn’t know it, but he just about saved Daisy’s life.

Despite his unusual beginnings, Lucky enjoyed life as any ordinary pony would. He became best friends with the children of his parents’ friends, Berry Bubblegum, Lickety-Split, Opal and Forelle. As a foal, he was teased relentlessly by the local bullies about his red and yellow eyes and the fact that his coat was slowly turning yellow. This did unfortunately cause him to be very image conscious about these small things he couldn’t control but he always relied on his best friend Lickety-Split to chase those bullies away.

Lucky is the least chaotic out of the Fluttercord children. He had chaotic powers, sure, but rarely needed to use them and was a relatively well behaved kid. He only every got into serious trouble once. Like his mother, Lucky can talk to animals but he seem to only use this ability to communicate with insects. Fascinated by what he learned from the insects, he poured himself into learning everything and anything he could. To say he was utterly obsessed was an understatement and his bedroom became a safe haven for all things creepy crawly. When Lucky was ten, he went of exploring to find more bugs, both to observe their natural behaviours and to add to his collection. He was gone for two days, sleeping in the woods with no shelter and feeding of wild berries and mushrooms, yet he loved every minute of it. However, he didn’t tell his parents before he left. Discord and Fluttershy were beside themselves in panic, fearing he had been taken as well. Discord’s magic didn’t work on his children so he couldn’t locate him. They were hugely relieved when Lucky walked through the front door, smiling with mud in his coat, twigs in his hair, carrying his various bugs and a brand new cutie mark of a ladybug on a leaf on his flank. He was also super grounded once he told them where he had been.

His early teenage years were challenging. Despite hating his eyes and horns, Lucky was (and still is) considered to be very handsome by many mares at school. Some even find his eyes and horns attractive in an edgy way, even though, personality-wise, he is far from that. However, he did develop a liking to pretty mares but was far too shy to ask them out himself, prompting Split to literally shove him into his crushes just to get him to talk to them. Lickety-Split wasn’t always the best wingman but it was far better than Lucky’s own father. Once Discord caught Lucky staring dreamily at Opal, Rarity’s daughter. He immediately made it his new life mission to set them up, pushing him to talk to her, magically conjuring gifts for Lucky to give her and setting up this most romantic dates ever. Each attempt embarrassed and irritated Lucky more and more. Discord even got Upsy Daisy roped into it, but only because she saw this as another opportunity to wind up Lucky.

Thankfully, Opal didn’t mind too much. She actually did develop feelings for Lucky during the two dranconequis’ meddling and she really wanted a nice guy after being treated like dirt by the rich famous jerks in Canterlot. After another one of Discord and Daisy’s date set ups, the pair managed to sneak away. They had their own ‘not-really-a-date’, exploring the forests around Ponyville on a midsummer night. It wasn’t long before they confessed their mutual feelings to each other and began dating. Discord still takes full credit for the success, much to Lucky and Fluttershy’s annoyance.

In the current timeline, Lucky is eighteen and in his last year of school. He would like to study insects and bugs as a career and plans to go to university once he is done with school. He is still dating Opal. Unfortunately, Discord has yet to stop pestering Lucky about that.

Bits and Pieces

The reason for Lucky’s existence didn't come to fruition until many years after he hatched. Twilight found a very old scroll on dragonequi, which explained a very rare instance of reproduction in the species. If a dragonequus feels the deepest and truest of love for another, it begins to create an egg made of that love, regardless of gender or if the other is a different species. Otherwise, dragonequi make babies the normal way. Discord didn't know about it as he hadn't been around his own kind for a very long time. After learning this, both Daisy and Lucky were afraid of the same thing happening to them when they were in their own relationships but luckily that never happened.

Lucky and Daisy care for each other very much, especially since Daisy considers Lucky to be her life saver. However, Lucky is just far to easy to annoy and Daisy finds it very funny.

Lucky wasn’t born with horns. One day, he complained about having a terrible headache all day, which got worse after bedtime. In the morning, a sleep deprived Lucky, trudged into the kitchen with his family staring at him. He had literally sprung up two identical goat horns overnight. Mortified at the thought to going to school like this, he begged Discord and Daisy to remove them when his attempts failed. But no matter how many times they made them disappear, the horns grew right back immediately. Like his eyes, he has since learned to live with them but that didn’t stop an embarrassing day at school with everyone staring and giggling at him.

Lucky has a draconequus from but he prefers his pony image.

As a baby, Upsy Daisy was quiet and never fussed at night. Lucky was the opposite. Every night, he would scream so loud, Discord had to soundproof the cottage as to not wake all of Ponyville again and brake every single window. Both parents had very restless night in those early days.

Lucky uses his chaos powers for his bug research, such as shrinking down to an ant’s size to interact with a colony.

Lucky was born green, like his grandfather and uncle, but the green gradually faded to yellow as he got older.

Like his mother, Lucky has a beautiful singing voice, though he is more comfortable singing in front of others. He and Fluttershy like to sing together a lot. When Opal has had a bad day, she asks Lucky to sing for her and it soothes her every time.

Lucky’s godmother is Treehugger. While Treezy loves to hang out with her little dude of a godchild, Lucky is a little uneasy about her. Sure, she loved nature just as much as he did but she was all about spirit, embracing, chakras and other strange things while he was into studying nature and insects for research. Not that he hated her, she was just too...odd for him (ironic considering his family).

Lucky’s romance with Opal is ridiculously sugary sweet and playful. Despite their differing interests, they adore spending time together, teasing and flirting with each other while taking picnics together. However, unlike Opal’s brother Ace Dany and his boyfriend Bramble, they strictly keep their flirtiness private.

Lucky is terrified of Fluttershy’s stare, something that’s impervious to Daisy and Hullabaloo.

Lucky Bug © Me

My Little Pony © Hasbro

#my little pony friendship is magic#My Little Pony#Next Gen#mlp next gen#lucky bug#ocs#original characters#Fan Characters#Fanart#fluttershy#fluttercord#discord mlp#digital art#MLP: FiM#mlp next generation#Upsy Daisy Verse

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Umbrella Academy Season 1 Episode 5

We start off the episode, not with a flashback, but with a flashforward. To when Five jumped ahead to the future. He's mainly just walking around a lot, carting Deloris and various things in a wagon. Deloris goes through various fashion statements depending on what time of the year it is (a fur muff hat in the winter, sunglasses and a tanktop in the summer). He does seem to have a sort of make-shift home when he's older.

One day, he's approached by a woman from the time traveling agency that Cha-Cha and Hazel work for. She tells him that the agency works to keep history on the right track. Five asks why didn't people stop the apparent apocalypse, but she laughs and says that it was meant to be. It's not the end of everything... just the end of something. She then offers him a job as an agent.

He worked there for a long time, but not as long as he should have according to the contract he made. Which is why Hazel and Cha-Cha are currently after him: for breach of contract. When he was supposed to...??? Assassinate JFK, I guess? He finally figured out what it would take in order to return to his own time. And then he jumped back to the academy the day of his father's funeral. And you know the rest from there.

He tells all of this to Luther back in Diego's boiler room bedroom. Luther takes it a lot better than Vanya did, and wants to help stop the end of the world.

Diego comes in and says about how his friend died, and demands that Five start talking. Five briefly mentions that he knows the people after him, but that they'll kill Diego if he tries to go after them, too.

Meanwhile, I guess Klaus accidentally time traveled. Back to the 1960's, for a year. And he was drafted, apparently, because he comes back with an army tattoo, dog tags, and a “military uniform”. Five later finds him, and says that he recognizes the symptoms of time travel “jet lag”. Klaus brushes him off, and leaves the house, but runs into Diego as he's leaving to get revenge on Hazel and Cha-Cha. Klaus is oddly silent in the car, which is something Diego remarks upon, because it's so strange. Klaus asks to be dropped off, and then goes into a “veteran's only bar”. There, he wanders around a bit before he starts crying before a picture up on one of the walls. The other vets, who are older, are getting kind of upset about the entire thing. Diego comes in before any vet can say anything, and asks Klaus what's going on.

Then, one of the vets tells Klaus that he has to leave, because this bar is only for veterans. Klaus gets upset and defensive, and says that he is a vet. He also tells the older vet to “fuck off”. Diego tries to defuse the situation by saying that his brother is drunk, and just wants to be on his way. The other vet says that he'll let them go when he gets an apology... from Klaus. Which Klaus gives to him... sort of. “I'm sorry... that you're such a stick in the mud!” Or something like that. This leads to a bar fight... which is both worrying and comical, considering that all of the bar patrons are older.

While that's going on, Hazel and Cha-Cha are in deep shit because Klaus took off with their time-travel what-have-you. And their bosses know it, because every trip is recorded in some office somewhere (somewhen).

There's this really bizarre scene where Hazel flirts with the doughnut shop waitress. This has been going on for some time now, but I feel like it reached a weird peak with this episode, where he activly hung out with her while she was on a break.

As he's leaving the shop, Diego and Klaus see him leaving. Diego I think recognizes the suit that he's wearing, and maybe the build. Klause recognizes him because he was unmaked during the second half of torturing him. They follow them back to the new motel that they're staying at, where Diego puts a tracker under their car.

However, Cha-Cha sees Diego outside. They get a message from the motel manager; it's from Five, saying that he has the briefcase, and wants to meet them. They sneak out the back, but Diego is on to them. However, while he and Klaus are away from the car (and Klaus shows some life-saving moves he learned during the war), one of the two slash the tires on Diego's car.

Back at the academy, Luther finds Five scribbling all over his walls with chalk. He asks what Five's doing, and Five says he's pin-pointed four individuals who he should kill in order to prevent the end of times. Luther asks about the first guy on the list, and is horrified when Five says that he thinks the guy is a gardener. Five says that it's the difference between one life vs billions... which when you've literally seen the wasteland, that's kind of a big deal. He pulls out a gun that used to belong to their father, which only upsets Luther more. Luther then grabs Deloris and hangs her out the window, and says that Five has to pick. Five picks Deloris, which means that Luther ends up with the gun.

They go out to the meeting spot, and Luther insists that he be the one to hold onto the fake time travel briefcase. Hazel and Cha-Cha show up, and Five asks for a meeting with their boss; he refuses to tell them why. Cha-Cha makes a call on a nearby payphone, and they all settle in to wait.

However, before any time traveler can show up, a creepy rendition of Ride of Valkyries starts to play. It's Diego and Klaus in a stolen ice-cream truck that was by their car in the motel parking lot. They crash into Cha-Cha and Hazel...

And all time stops, except for Five. The same agent as before shows up and chastises him in his efforts to save the world. She then offers him a job... in time travel management. Because he's a good agent. He scoffs over this, but he does make a deal with her: that he only just wants his family to survive. She promises to see what she can do. Before she unstops time, Five tosses Hazel's gun away, and moves a bullet so that it's not going to hit Luther.

Time unfreezes, the bullet hits the car, and the truck crashes into Hazel's and Cha-Cha's car. Luther tosses the briefcase away, which Hazel runs over to grab. Luther then grabs Diego and Klaus from the now ruined ice-cream truck, and they speed away, abandoning the time traveling duo in the middle of nowhere. (Five meanwhile, left with the lady. Luther seems baffled by Five's disappearance, but he rolls with it.)

While that's going on, there's a subplot with Allison, Vanya, and Leonard. Allison keeps insisting that Leonard is creepy, but Vanya is angry at her sister, stating that she doesn't get to just be out of Vanya's life for so long, and then come in and say weird things like “don't date this guy!”

Vanya goes to meet Leonard for breakfast, where she tells him that the first chair violin player (the nasty bitch from an earlier episode) has “mysteriously” disappeared. (We'll get to this in a moment.) Leonard encourages Vanya to try out for the first chair spot, because it's her time to shine. Vanya is happy because nobody has ever actually encouraged her before.

Meanwhile, Allison looks through microfiche at the library, in search of Leonard. (At the same time, across the table from Allison, Cha-Cha does research on the Umbrella Academy, and ends up reading Vanya's book, but I don't know how much good that actually researching did either of them...) Later, Allison goes back to Vanya's apartment to tell her that she tried to look up Leonard in the paper, and couldn't find much of him. Vanya scoffs over this as actual evidence, because most people aren't in the paper on a daily basis, Ms. Super celebrity.

Allison still isn't convinced over this, so she breaks into Leonard's house. I don't know if she found anything in the main part of the house, but before she's about to pull down the door to the attic, Leonard comes home, so she sneaks out. (And we'll get to the attic in a moment, too.)

Vanya goes to her audition, where the conductor still doesn't know who the fuck Vanya is. However, as Vanya starts to play, a weird energy drifts out from her, and falls over the conductor and two ladies who are sitting behind him.

She later goes to Leonard to tell him that she got first chair (and the solo being first chair comes with). She says that she was uncertain about it,because it's the first time that she's ever played without her medication. Which is something that we've seen her taking throughout the series so far. In the previous episode, after Leonard made breakfast plans with Vanya, he was seen dumping out her pills into the sink. They kiss, and start to get hot and heavy on the sofa.

As they're doing that, the same strange energy radiates from Vanya, through the house, and up to the attic. There, we see what Allison did: the shitty violinist, wrapped in plastic and clearly dead. Reginald's journal that Klaus threw away. And probably a bunch of other stuff like that that I can't identify.

The energy leaves the house, and travels to the academy. I think Pogo senses it. He then turns to Grace, who he has repaired. He asks that she keep something a secret from the children.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I write this on my iPhone, sitting next to my dad, who is currently getting his 4th Chemo Therapy Treatment of Carboplatin and Taxol. The drugs are chemical bombs and each week the accumulative damage grows. They pre-treat him with histamine blocking meds so he doesn’t have reactions, but he has reactions during the infusion, like he can’t breath. The nurses are well aware and calmly manage the reactions with more meds. These meds cause him to become very drowsy, so the remainder of the day becomes about keeping him from falling.

I still am trying to process all that has occurred since early August 2018. I look back on these pictures of our last outing at Lake Jocassee and never would have guessed how things would change just a week later. I’ve often wondered how cancer strikes people so quickly, now I know. I am writing this so I will never forget each minute that will forever live with me. I am also using this as a way to cope and understand something that is unfamiliar and terrifying.

My parents have always taken care of themselves and one another. They have been very lucky to have good health and I have been lucky to have them as energetic as they are in their eighties. When they moved up here from Florida, I was delighted I was going to finally be able to spend more time with them - like daily and weekly vs. just twice a year. They moved 15 minutes away or a lovely 60 min bike ride through rolling countryside and mountains. I was giddy and felt the universe shift a bit. I felt pulled to them. They are in fact two of the coolest, funniest, and open-minded people I know.

Shortly after this kayak trip (photos above) they decided to make a pact to live to 100 and created a “bucket list”. They were thankful for their health and never took it for granted. Perhaps the bucket list idea was a way to for them to celebrate how young they felt or perhaps they recognized they were chronologically getting up there.

Paddling on Jocassee was relaxing, calm, and beautiful; Certainly an experience they would have loved to have recreated again and I am hopeful they will. It may look different in the future, but I suspect the beauty and calmness of the lake will bath their brains in peace.

A week after snapping these pics, I got a call from my mom, she was on her way to the ER with my Dad. I was working one floor up and met them in the ER. While we waited, I learned my Dad had been feeling fatigued for several months and had developed shortness of breath over last few weeks. It wasn’t evident on the kayak trip that he was struggling, but it was obvious in the ER. My mom said they had been to their primary care several times and their primary care doc reassured him it was natural aging, as tests did not reveal anything to be concerned about.

As we sat for 6 hours in the waiting area, I was certain it was nothing serious. Afterall, my dad had no other health issues other than a little hypertension. His meds consisted of an 81 mg baby aspirin and amlodipine 2.5 mg each day - what a lucky guy. I was thinking maybe he had pleurisy or walking pneumonia.

We finally were shown to a room and labs were drawn. We were relieved to finally get things moving. By this time my sister, Lori, and I were getting silly from the fatigue of waiting. We were thoroughly entertained by a belligerent drunk guy on a stretcher in the halllway who seemed to draw all the attention of the medical staff while we well-behaved folks waited for answers.

I noticed my dad’s HR would easily jump to a sinus tach in the 130s with just a little bit of movement. Something didn’t seem right, but I was not going to speculate or think the worst. I was just his daughter, at his side, keeping the mood light.

We were informed by the physician assistant caring for us that his left diaphragm was elevated and was probably the cause of his shortness of breath. I was a little taken back as this was an unusual finding that left me with a knot in my stomach. Not too long after this finding he was whisked away for a CT of his chest.

He returned to the room and we waited for results. The PA came in with a sticky note and said she read off it: “You have a very large anterior mediastinal mass...No one here will operate because of your age...We are discharging you and you will need to see an oncologist.”

Our mouths dropped. My stomach bottomed-out as she said “mass” and my face flushed. We all just blankly looked at one another. Go home?

I spoke to a good nurse friend in recovery and she called the thoracic resident. I spoke to the PA who delivered the news and said, “We can’t go home. He is short of breath. He and my mom live alone. His Heart rate is bouncing up to 130s. He is weak. Please admit him and consult thoracic surgery.” My dad chimes in, “I’m not a throw away!” Meaning he doesn’t want to be dismissed because of his chronological age. He was far healthier than most half his age and this deserved a second look. The radiologist who read the report never actually saw my dad, but he did see a birthdate.

The next day, the interventional radiologist who read his CT and gave us the crappy news also did a needle biopsy of this baseball size mass.

We went home on a Wednesday after 2 days and waited. We were waiting for results and waiting for an appointment with a thoracic surgeon. Waiting is tough and if you are sick you will learn the meaning of patience.

We made it to Sunday when I thought something wasn’t right with my dad. He continued to have episodes of shortness of breath, but something was still off. I knew he had anxiety, but this was different. He said he felt fine and I almost left it at that. As a nurse you learn to listen to your 6th sense.

My parents live in a remote part of the county where everything is 30 min away. I left there house and an hour later returned with a pulse oximeter that I purchased from a CVS drug store. His oxygenation was 95% not bad for a guy now breathing 40 times a minute with 1.25 lung capacity. However, his pulse read 155 and I was baffled. No way?! I palpated his radial artery and it was a match. Off we went to the ER...

ER visit number II was faster as we went to a smaller satellite hospital 30 min from their home. The rhythm was too fast on the monitor to establish what it was so the ER MD attempted to chemically cardiovert him with adenosine. Adenosine is pushed quickly through an IV. It stops and restarts the heart. I can not lie, I was nervous. It’s so diffferent when this is your own family member. My mom tearfully excused herself and I stayed by his bedside. The ER doc informed my dad it would suck, and we proceeded. It sucked. He felt his heart stop and I watched his eyes bulge and panic come across his face for 3 of the longest seconds of my life. We were able to see he had an underlying atrial flutter. We were started on a verapamil drip and were transported to the main hospital for management by a cardiologist. His heart converted back to a normal rhythm on the verapamil drip before we left the ER in transport to Main hospital at 1 am. We were under the impression it was stress related to the new shitty diagnosis and having to wait on results.

The next day he had an echocardiogram to look at the structure and function of his heart. He was started on a Metoprolol a drug that blocks adrenaline and keeps heart rate lower and it was doing its’ job.

He spent 2 nights in hospital and outside of naps, lacked solid hours of good sleep. We finally got word that his ECHO results were good. No one said a word about metastatic disease to his pericardium. We were told he had a small ring of fluid within the pericardial sack, but it wasn’t a lot and certainly not something they felt needed draining. The atrial flutter responded well to the metoprolol and we were discharged home to once again wait for our thoracic surgery appointment.

We finally made it to the thoracic surgeon to learn of what was growing in my dad’s mediastinum. I was hoping for a thymoma, but instead we drew the really short stick with a highly aggressive, highly invasive cancer called: Squamos Cell Thymic Carcinoma.

WTF? Come on! Can we not catch a break here?

I had never heard of this type of cancer and neither have many in the medical field cause in addition to being aggressive and invasive, it is also a rare tumor. A rare tumor that hasn’t impacted enough lives that researchers devote a lot of time, money and effort into understanding it. Not only that, but sadly, most people die before any data can be collected. Once you get short of breath, dry cough and fatigue it is usually advanced.

PET Scan had some questionable lymph nodes light up, but no other disease was noted distal to the mediastinal cavity.

We hoped it could be removed. Excising the tumor was first choice in the management of this cancer and had the best outcomes, but to do this the surgeon would need to get clean margins. The thoracic surgeon wanted a cardiac MRI to examine if this tumor had invaded any of his great vessels. CT scans had only shown that the tumor was abutting the ascending aorta, but we needed to be certain cause the surgery involved opening his sternum with a saw and recovery would be 5-6 weeks. The surgeon emphasized that he didn’t want to operate and create trauma without being able to get the entire tumor. He didn’t want to delay care in a time-is-of-the-essence scenario.

It was 6pm on a Monday evening just days out from last hospitalization, when I returned to their house to check on him. Earlier that morning, my mom and I took his mini Pomeranian back to the vet and learned it was dying. The vet apologized and said it was time. We put my dad’s 18 y/o Pom, Ben, to sleep at 10:30. My mom held him and he passed. We were a mess. We told my dad and his response seemed flat. Distant.Something else was on his mind.

I stayed close and felt something was amiss, something was unfolding, progressing. I was thinking is he getting an infection? His temp was 100.2, slightly more SOB, and his pulse was 95-110 at rest, on a beta blocker. Nowhere near his norm and I could not ignore this or excuse it. My dad is precious to me. I looked at my mom and dad, apologized as I informed them we needed to go back to the ER. They were agreeable. I think he was relieved I recognized something was wrong.

Shortly after arrival at the satellite ER labs were drawn and ultrasound of his heart was done by ER doc. He said there appeared to be a large fluid collection around my dad’s heart. We were again admitted to ICU for a condition called Cardiac Tamponade. Early the next morning he had the fluid drained 600 ml from around his heart. The fluid build up which is inside the pericardial sac squeezes the heart. The heart can be stunned and go into failure. The fluid that was drawn off was sent for cytology. It was suspicious. It was likely metastatic disease.

In fact after annoying the cardiologist with repeated questions in the hallway, he motioned me over to his computer screen. He showed me the ECHO and pointed out the thickening of the pericardium and showed me a mass dangling from his ventricle. I didn’t need to wait for cytology. This was confirmation for me that we were very far into a disease process. My face flushed, my heart sank, and my stomach dropped as I comprehended the situation. I thanked the MD and my mom asked what he was showing me. I told her. I saw the color leave her face.

The thoracic surgeon was still hoping to remove the mass as the CT didn’t show it had invaded the great vessels, but he did want a Cardiac MRI which was on the back burner. We were still in ICU cause the Cardiac Tamponade and procedure to drain the fluid triggered a lot of Atrial Flutter and Atrial Fibrillation. We waited for the Cardiac MRI for 3 days. There is only one machine and his was repeated twice before they got quality images. The thoracic surgeon finally met with us and after consulting his partners, radiologist, and oncologist, it was decided surgery was just too risky and he wasn’t certain he could get clear margins. He stressed how he didn’t want to create more problems or delay my dad in getting treatment if there were complications. We very much appreciated the thoughtfulness of his answer. We really didn’t have a minute to spare. The surgeon decided to cut a window in my dad’s heart so the cancer did not build up more fluid and compress this vital organ again. The cancer cells would drain into his belly instead of filling the pericardial sack.

We were discharged home in a questionable state: weak. At first we were told he would stay until he was walking well, but the hospital was full and we were off-loaded unexpectedly. Home is a place with stairs. Stairs to to get in and stairs to get out and the most movement he had done in a week was walking 25 ft with a walker and that was exhausting for him. I was concerned about falls. How were me and my mom going to get 170 lb man up 5 steps safely? He was too weak. He hadn’t eaten, he had not slept in 10 days. We were behind the eight ball and chemo had not even started.

Chemo is rough. To survive chemo, one needs some level of fitness, meaning able to perform ADLs independently and move often. We were overwhelmed. The next week was labor intensive and emotionally draining. Here we were home and we were struggling. He still wasn’t eating, still not sleeping, and my radar was on constant alert. I spent my days observing and looking for subtle changes. Oh and there were changes that needed immediate attention as he flipped in and out of rapid atrial fibrillation and got urinary tract infection.

I was scared and my dad was terrified. In times when we were alone, he would ask me: “How did this happen?” He would shake his head as if disappointed in his body. Disbelief. He was unable to comprehend it and he too was terrified.

To be continued...

1 note

·

View note

Text

I could hear things, and Icould feel terrible pain: when anaesthesia fails

The long read: Anaesthesia remains a mysterious and inexact science and thousands of patients still wake up on the operating table every year

When Rachel Benmayor was admitted to hospital, eight and a half months pregnant, in 1990, her blood pressure had been alarmingly high and her doctor had told her to stay in bed and get as much rest as possible before the baby came. But her blood pressure kept rising this condition, known as pre-eclampsia, is not uncommon but can lead to sometimes-fatal complications and the doctors decided to induce the birth. When her cervix failed to dilate properly after 17 hours of labour, they decided instead to deliver the child by caesarean section under general anaesthetic. Rachel remembers being wheeled into the operating theatre. She remembers the mask, the gas. But then, as the surgeon made the first incision, she woke up.

I remember going on to the operating table, she told me. I remember an injection in my arm, and I remember the gas going over, and Glenn, my partner, and Sue, my midwife, standing beside me. And then I blacked out. And then the first thing I can remember is being conscious, basically, of pain. And being conscious of a sound that was loud and then echoed away. A rhythmical sound, almost like a ticking, or a tapping. And pain. I remember feeling a most incredible pressure on my belly, as though a truck was driving back and forth, back and forth across it.

A few months after the operation, someone explained to Rachel that when you open up the abdominal cavity, the air rushing on to the unprotected internal organs gives rise to a feeling of great pressure. But in that moment, lying there in surgery, she still had no idea what was happening. She thought she had been in a car accident. All I knew was that I could hear things and that I could feel the most terrible pain. I didnt know where I was. I didnt know I was having an operation. I was just conscious of the pain.

Every day, specialist doctors known as anaesthetists (or, in the US, anesthesiologists) put hundreds of thousands of people into chemical comas to enable other doctors to enter and alter our insides. Then they bring us back again. But quite how this daily extinction happens and un-happens remains uncertain. Researchers know that a general anaesthetic acts on the central nervous system reacting with the slick membranes of the nerve cells in the brain to suspend responses such as sight, touch and awareness. But they still cant agree on just what it is that happens in those areas of the brain, or which of the things that happen matter the most, or why they sometimes happen differently with different anaesthetics, or even on the manner a sunset? an eclipse? in which the human brain segues from conscious to not.

Nor, as it turns out, can anaesthetists accurately measure what it is they do.

For as long as doctors have been sending people under, they have been trying to fathom exactly how deep they have sent them. In the early days, this meant relying on signals from the body; later, on calculations based on the concentration in the blood of the various gases used. Recent years have seen the development of brain monitors that translate the brains electrical activity into a numeric scale a de facto consciousness meter. For all that, doctors still have no way of knowing for sure how deeply an individual patient is anaesthetised or even if that person is unconscious at all.

Anaesthetists have at their disposal a regularly changing array of mind-altering drugs some inhalable, some injectable, some short-acting, some long, some narcotic, some hallucinogenic which act in different and often uncertain ways on different parts of the brain. Some such as ether, nitrous oxide (better known as laughing gas) and, more recently, ketamine moonlight as party drugs. (If you have an inclination to travel, take the ether you go beyond the furthest star, wrote the American philosopher-poet Henry David Thoreau after inhaling the drug for the fitting of his false teeth.) Different anaesthetists mix up different combinations. Each has a favourite recipe. There is no standard dose.

Todays anaesthetic cocktails have three main elements: hypnotics designed to render you unconscious and keep you that way; analgesics to control pain; and, in many cases, a muscle relaxant (neuromuscular blockade) that prevents you from moving on the operating table. Hypnotics such as ether, nitrous oxide and their modern pharmaceutical equivalents are powerful drugs and not very discriminating. In blotting out consciousness, they can suppress not only the senses, but also the cardiovascular system: heart rate, blood pressure the bodys engine. When you take your old dog on its last journey, your vet will use an overdose of hypnotics to put him down. Every time you have a general anaesthetic, you take a trip towards death and back. The more hypnotics your doctor puts in, the longer you take to recover, and the more likely it is that something will go wrong. The less your doctor puts in, the more likely that you will wake. It is a balancing act, and anaesthetists are very good at it. But it doesnt alter the fact that for as long as anaesthetists have been putting them to sleep, patients have been waking during surgery.

As Rachels caesarean proceeded, she became aware of voices, though not of what was being said. She realised that she was not breathing, and started trying to inhale. I was just trying desperately to breathe, to breathe in. I realised that if I didnt breathe soon, I was going to die, she told me.

She didnt know there was a machine breathing for her. In the end I realised that I couldnt breathe, and that I should just let happen what was going to happen, so I stopped fighting it. By now, however, she was in panic. I couldnt cope with the pain. It seemed to be going on and on and on, and I didnt know what it was. Then she started hearing the voices again. And this time she could understand them. I could hear them talking about things about people, what they did on the weekend, and then I could hear them saying, Oh look, here she is, here the baby is, and things like that, and I realised then that I was conscious during the operation. I tried to start letting them know at that point. I tried moving, and I realised that I was totally and completely paralysed.

The chances of this happening to you or me are remote and, with advances in monitoring equipment, considerably more remote than 25 years ago. Figures vary (sometimes wildly, depending in part on how they are gathered) but big American and European studies using structured post-operative interviews have shown that one to two patients in 1,000 report waking under anaesthesia. More, it seems, in China. More again in Spain. Twenty to forty thousand people are estimated to remember waking each year in the US alone. Of these, only a small proportion are likely to feel pain, let alone the sort of agonies described above. But the impact can be devastating.

For Rachel, sleepless and terrified in her hospital room, it was the beginning of years of nightmares, panic attacks and psychiatric therapy. Soon after she gave birth, her blood pressure soared. I was in a hell of a state, she told me.

For weeks after she returned home, she would have panic attacks during which she felt she couldnt breathe. Although she says the hospital acknowledged the mistake and the superintendent apologised to her, beyond that she does not recall getting any help from the institution no explanation or counselling or offer of compensation. It did not occur to her to ask.

Things can go wrong. Equipment can fail a faulty monitor, a leaking tube. Certain operations caesareans, heart and trauma surgery require relatively light anaesthetics, and there the risk is increased as much as tenfold. One study in the 1980s found that close to half of those interviewed after trauma surgery remembered parts of the operation, although these days, with better drugs and monitoring, the figure for high-risk surgery is generally estimated at closer to one in 100. Certain types of anaesthetics (those delivered into your bloodstream, rather than those you inhale) raise the risk if used alone. Certain types of people, too, are more likely to wake during surgery: women, fat people, redheads; drug abusers, particularly if they dont mention their history. Children wake far more often than adults, but dont seem to be as concerned about it (or perhaps are less likely to discuss it). Some people may simply have a genetic predisposition to awareness. Human error plays a part.

But even without all this, anaesthesia remains an inexact science. An amount that will put one robust young man out cold will leave another still chatting to surgeons. More than a decade ago, I found this quote in an introductory anaesthesia paper on a University of Sydney website: There is no way that we can be sure that a given patient is asleep, particularly once they are paralysed and cannot move.

Last time I searched, the paper had been adjusted slightly to acknowledge recent advances in brain monitoring, but the message remained the same: just because a person appears to be unconscious, it does not mean they are.

In a way, continued the original version of the paper, the art of anaesthesia is a sophisticated form of guesswork. It really is art more than science We try to give the right doses of the right drugs and hope the patient is unconscious.

The death rate from general anaesthesia has dropped in the past 30 years, from about one in 20,000 to one or two in 200,000; and the incidence of awareness from one or two cases per 100 to one or two per 1,000. Obviously we give anaesthetics and weve got very good control over it, a senior anaesthetist told me, but in real philosophical and physiological terms, we dont know how anaesthesia works.

It is perhaps the most brilliant and baffling gift of modern medicine: the disappearing act that enables doctors and dentists to carry out surgery and other procedures that would otherwise be impossibly, often fatally, painful.

The term anaesthesia was appropriated from the Greek by New England physician and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1846, to describe the effect of the drug ether following its first successful public demonstration in surgery. Anaesthetise: to render insensible. These days there are other sorts of anaesthetics that can numb a tooth or a torso, simply (or unsimply) by switching off the nerves in the relevant part of the body. But the most widespread and intriguing application of this skill is what is now known as general anaesthesia.

The first public demonstration of the use of inhaled ether as a surgical anaesthetic in 1846 by an American dentist, William Thomas Green Morton. Photograph: Design Pics Inc/Rex/Shutterstock

In general anaesthesia, it is not the nerve endings that are switched off, but your brain or, at least, parts of it. These, it seems, include the connections that somehow enable the operation of our sense of self, or (loosely) consciousness, as well as the parts of the brain responsible for processing messages from the nerves telling us we are in pain: the neurological equivalent of shooting the messenger. Which is, of course, a good thing.

I am one of the hundreds of millions of humans alive today who have undergone a general anaesthetic. It is an experience now so common as to be mundane. Anaesthesia has become a remarkably safe endeavour: less an event than a short and unremarkable hiatus. The fact that this hiatus has been possible for fewer than two of the 2,000 or so centuries of human history; the fact that only since then have we been able to routinely undergo such violent bodily assaults and survive; the fact that anaesthetics themselves are potent and sometimes unpredictable drugs all this seems to have been largely forgotten. Anaesthesia has freed surgeons to saw like carpenters through the bony fortress of the ribs. It has made it possible for a doctor to hold in her hand a steadily beating heart. It is a powerful gift. But what exactly is it?

Part of the difficulty in talking about anaesthesia is that any discussion veers almost immediately on to the mystery of consciousness. And despite a renewed focus in recent decades, scientists cannot yet even agree on the terms of that debate, let alone settle it.

Is consciousness one state or many? Can it be wholly explained in terms of specific brain regions and processes, or is it something more? Is it even a mystery? Or just an unsolved puzzle? And in either case, can any single explanation account for a spectrum of experience that includes both sentience (what it feels like to experience sound, sensation, colour) and self-awareness (what it feels like to be me the subjective certainty of my own existence)? Anaesthetists point out that you dont have to know how an engine works to drive a car. But stray off the bitumen, and it is surprising how quickly pharmacology and neurology give way to philosophy: if a scalpel cuts into an unconscious body, can it still cause pain? And then ethics: if, under anaesthesia, you feel pain but forget it almost in the moment, does it matter?

Greg Deacon, a former head of the Australian Society of Anaesthetists, told me about a patient who was waiting to have open heart surgery. Deacon had been preparing to anaesthetise him, he said, when the man went into cardiac arrest. The team managed to restart the recalcitrant heart, then raced the patient into surgery, where they operated immediately. It was only once the operation had begun, the mans heart now beating steadily, that they could safely administer an anaesthetic. It all went well, said Deacon, and the man made an excellent recovery. Some days later, the patient told doctors he remembered the early parts of the procedure before he was given the drugs.

That is a sort of incidence of awareness which was thoroughly understandable and acceptable, Deacon told me: he had not even known if the mans brain was still working, let alone whether he would survive an anaesthetic. We were trying to keep him alive.

This is not denial. This is the tightrope that anaesthetists walk every day. They just tend not to talk about it.

In 2004, and against a backdrop of growing public and media concern, Americas Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations finally issued an alert to more than 15,000 of the nations hospitals and healthcare providers. The commission, which evaluates healthcare providers, acknowledged that the experience of awareness in anaesthesia was under-recognised and under-treated, and called on all healthcare providers to start educating staff about the problem.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists subsequently acknowledged, in a 2006 practice advisory, that accidental intraoperative awareness, while rare, might be followed by significant psychological sequelae and affected patients may remain severely disabled for extended periods of time.

Before that acknowledgment was published, however, then ASA president Roger Litwiller made a small but telling observation. Despite his organisations concern about anaesthetic awareness, he did not want the issue to be blown out of proportion: I would also like to say that there is a potential for this subject of awareness to be sensationalised. We are concerned that patients become unduly frightened during what is already a very emotional time for them.

This is the anaesthetists dilemma. Under stress which affects just about everybody facing a general anaesthetic we lose our ability and often desire to process complex information. More than half of all patients worry about pain, paralysis and distress. High anxiety or resistance to the idea of anaesthesia may even contribute to anaesthetics failing, or at least increase the chances that we will remember parts of the operation. The more anxious we are, the more anaesthetic it may take to put us to sleep.

This creates a quandary for doctors: how much to tell? When we are anxious, our bodies increase production of adrenaline-type substances called catecholamines. These can react badly with some anaesthetic agents. So what does an anaesthetist tell a patient who, because of the type of operation, or their state of health, is at higher than average risk?

I mean, were trying to make people not worry about it, said one Australian anaesthetist I spoke with, but in the process I think we blur it so much that people hardly ever think about it, and thats probably not right either Should I be telling you that youve got a high risk of death? Is that going to frighten you to death?

Today the profession makes much of the emergence of a new generation of anaesthetists who are more attuned to the experiences of their patients. But the reality is that anaesthetists remain for the large part the invisible men and women of surgery. Many patients still dont meet them until just before or sometimes after the operation, and many, muffled in a fug of drugs, might not even remember these meetings. Nor do anaesthetists generally leave anything to show for their work: no scars or prognoses. When they do leave evidence, it is invariably unwelcome nausea, a raw throat, sometimes a tooth chipped as the breathing tube is inserted, sometimes a memory of the surgery. It is unsurprising, then, that by the time an anaesthetist makes it into the popular media, he or she is generally accompanied by a lawyer.

For the doctors who each day make possible the miraculous vanishing act at the heart of modern surgery, this invisibility can be galling. It is not surgeons who have enabled the proliferation of surgical operations numbering in the hundreds 170-odd years ago and the hundreds of millions today. It is anaesthetists. In hospital emergency rooms in Australia and other countries, it is not surgeons who decide which patient is most in need of and mostly likely to survive emergency surgery: anaesthetists increasingly oversee the pragmatic hierarchy of triage. And if you have an operation, although it is your surgeon who manages the moist, intricate mechanics of the matter, it is your anaesthetist who keeps you alive.

One of the first articles I came across when I started researching this subject was a 1998 paper by British psychologist Michael Wang entitled Inadequate Anaesthesia as a Cause of Psychopathology. Wang pointed out that pain even unexpectedly severe pain did not necessarily lead to trauma. Post-traumatic stress seldom followed childbirth, for example. What could be devastating, he said, was the totally unexpected experience of complete paralysis.

Even today, most patients undergoing major surgery have no idea that part of the anaesthetic mix will be a modern pharmaceutical version of curare, a poison derived from a South American plant, which causes paralysis. Few will be aware, either, that during surgery their eyes will be taped shut, that they may be tied down, and that they will have a plastic tube manoeuvred into their reluctant airway, past the soft palate and the vocal cords, overriding the gag reflex, and into the windpipe.

An anaesthetist checking a patients pupil to gauge the effect of an anaesthetic. Photograph: Cornell Capa/The Life Picture Collection/Getty Images

For the patient paralysed upon the table, said Wang, [t]he realisation of consciousness of which theatre staff are evidently oblivious, along with increasingly frenetic yet futile attempts to signal with various body parts, leads rapidly to the conclusion that something has gone seriously wrong. The patient might believe that the surgeon has accidentally severed the spinal cord, or that some unusual drug reaction has occurred, rendering her totally paralysed, not just during the surgery, but for the rest of her life.

As soon as anaesthetists explain to patients how the process works, it all starts to seem a lot less mysterious. And talk, it turns out, is not only cheap but effective: a preoperative visit from an anaesthetist has been shown to be better than a tranquilliser at keeping patients calm. I know from my own experience I had surgery on my spine how reassuring such a conversation can be. For me, it was not just the information; it was the fact of the human contact, of being treated as an equal, of being included, rather than feeling like an appendage to a process to which I was, after all, central.

Hank Bennett, an American psychologist, remembers a young girl whose mother brought her to see him some time after the girl had her adenoids removed. The surgeon referred the mother to Bennett after she had returned to him in a state of anxiety about her child. The surgery had been straightforward, but the mother felt that something was very wrong with her previously happy daughter: the child had withdrawn from her family and friends, and had stopped working at school. She could no longer fall asleep without her mother sitting with her, and was afraid of the dark.

Bennett spoke with the girl. He told her there must be a reason she had changed her behaviour, and asked if it might have something to do with the operation.

Bennett recalled: And she said, Yes. They saidthat they were going to put me to sleep, but the next thing I knew, I couldnt breathe. Now, she was only momentarily like that she does not remember the breathing tube going in but when I asked why she was doing these things differently at school and at home, she said: Well, I have to concentrate and I cant be bothered by anything. Ive got to make sure that I can breathe.

Bennett referred the girl to a child psychologist, and within weeks she was back to herself. Today she would be approaching middle age. But lets say that was just luck, Bennett says now. What if nothing had been picked up about that? Would she have been permanently changed? I think that you would say, yes, she probably would have been.

So if you were my anaesthetist and I your patient, there are some other things Id hope you would do in the operating theatre. Things that many already do. Be kind. Talk to me. Just a bit of information and reassurance. Use my name. Patients who remember waking are often greatly relieved at having been told what was happening to them, and reassured that this was OK and that they would now drift back to sleep.

The Fifth National Audit Project on accidental awareness during general anaesthesia states: The patients interpretation of what is happening at the time of the awareness seems central to its later impact; explanation and reassurance during suspected accidental awareness during general anaesthesia or at the time of report seems beneficial. Hospital staff could put a sign on the wall of the operating theatre: The patient can hear. Because one of the strange things about anaesthetic drugs is that they can exert their effect in each direction not just upon the patient, but upon the doctors and theatre staff performing the procedure.

After the teenage son of a good friend was badly burned in an accident some years ago, he had to endure weeks of intense pain, culminating each week in the agonising ritual of nurses changing the dressings on his chest and arms. They did this by giving him a dose of a sedative drug designed to distract him from the pain and prevent him remembering it. My friend would attempt to comfort her son as he yelled and as the nurses got on with their difficult task. What she observed was that while the drugs did give her son some distance from his pain, and certainly his memories of it, they also gave the nurses some distance from her son. It was an understandable, perhaps necessary, distance; but inherent in that tiny retreat (the lack of eye contact, the too-bright voices) was a loosening of the tiny filaments that connect us one to another, and through which we know we are connected.

It is a process inevitably magnified in the operating theatre, where the patient is silent and still, to all intents absent, and where their descent into unconsciousness is routinely accompanied by the sounds of the music being cranked up (one prominent Australian surgeon is said to favour heavy metal), and conversation. It need not take a scientific study to tell us that this deepening of respect and focus is good not only for patients, but for doctors, too. In the end, it might not even much matter what you say. During an operation, a soothing voice may be more important than what the voice says, writes psychologist John Kihlstrom, who still encourages anaesthetists to talk to their anaesthetised patients (about what is going on, giving reassurance, things like that) but acknowledges that he doesnt expect them to understand any of it not verbally at least.

Japanese anaesthetist Jiro Kurata calls this care of the soul. In an unusual and rather lovely paper delivered at the Ninth International Symposium on Memory and Awareness in Anaesthesia in 2015, he wondered if there might be part of our existence that cannot ever be shut down, which we cannot even conceive by ourselves a subconscious self that might be resistant to even high doses of anaesthetics. He called this the hard problem of anaesthesia awareness. I have no idea what his colleagues made of it. But his conclusion seems unassailable.

Any solution? Science? Yes and no. Monitoring? Yes and no. Respect? Yes. We must not only be aware of the inherent limitation of science and technology but, most importantly, also of the inherent dignity of each personal self.

Anaesthesia: The Gift of Oblivion and the Mystery of Consciousness by Kate Cole-Adams (Text Publishing Company, 12.99) is published on 22 February. To order a copy for 9.99, go to guardianbookshop.com

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign up to the long read weekly email here.

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/feb/09/i-could-hear-things-and-i-could-feel-terrible-pain-when-anaesthesia-fails

from Viral News HQ https://ift.tt/2IeNgzY via Viral News HQ

0 notes

Text

I could hear things, and Icould feel terrible pain: when anaesthesia fails