#vesnin brothers

Text

Moscow's Lower Presnya - factory workers' village built in late 1920s

Thank you for making it happen: K. T., H. W., T. B., m., @depetium, @transarkadydzyubin, S. R.

Presnya in Moscow was a district of factories since the 18th century. Some of the factories that were based here are the Prokhorov's textile factory (Tryokhgornaya Manufactura), Smith's boiler factory, Danilovsky sugar factory, Ossovetsky's chemical plants etc. Factory workers usually lived close by (some of the factory owners built housing, but not all) so there were a wide array of houses and buildings (some brick, some wooden). After the 1917 Revolution all of the factories were nationalised and workers' living situation rethinked.

Presnya was the first workers' village in Moscow rebuilt after the Revolution (began in 1926). Emerged a district of 4-floor brick houses in formations that created court yards (something that didn't really exist for apartment buildings before then). Court yards were there purely for comfort of the residents. The new buildings mostly consisted of standard sections of 2 or 4 flats per floor per entrance. The standartisation helped bring the costs down (the buildings themselves were all still different). Buildings stood far enough from each other to allow enough air and sunlight. Most of the flats had windows facing North and South - it helped with air flow and sanitation (tuberculosis and other diseases were on the rise, and having direct sunlight in the flat was detrimental for germs). Many of the flats (though not all) had kitchens and bathrooms. Every building had a built-in boiler room that provided heating in winter. Flats were equipped with their own boilers to cook and heat water. Some other "smart house" solutions in the flats: a pipe system that sent heated water from the kitched to the bathroom, oven-samovar connector (to simplify boiling a samovar), built-in "ice pantry" in the kitchen (served as a fridge in wintertime), air ducts in every room, floor air ducts that also served as water retractors and prevented flooding the neighbours downstairs.

It's important to note that while some families had a whole flat to themselves, most of them were kommunalkas [communal flats] with several families sharing one flat, one room per family. Typically, workers aged 40+ with big families were more likely to get their own flat that younger or unmarried workers.

Let's see some of the residential buildings!

First, some of the 19th century ones - originally built by factory owners as housing for workers.

This new elite residence is built over three 19th cent. buildings. They tried to save as much as possible. The building on the left is mostly as is (only an extra floor was added on top), the building on the far right was kept as part of the facade, and the middle one was in too bad a condition to save, unfortunately.

Corner house with the Kommunar store - designed by Aleksandr Kurovsky.

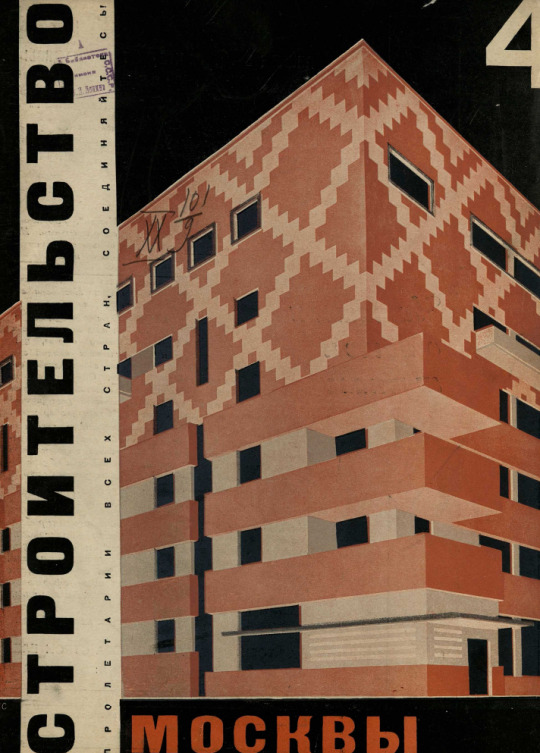

Another building designed by Kurovsky was initially supposed to have more balconies - see the project on the cover of Building Moscow (#4, 1929). Originally the colors were reversed: the building was made of red brick (befitting the red brick factory surroundings) and the patterns were made of lime brick.

Pair of buildings designed by engineer Osvald Kapran are very simple but have a distinct feature.

And finally the architectural dominant of the Lower Presnya - Mostorg [Moscow Trade] department store designed by Brothers Vesnin and built in 1928. It was their first constructivist building in Moscow. This was the first and only store of this magnitute in the district, a symbol of the new centralised trade as opposed to old style markets.

Part one - Architecture | Part two - Museum

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vesnin Brothers – Leningradskaya Pravda Office Building

1924, Moscow (RU)

Competition entry

via #1, #2

111 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Viktor Vesnin, Leonid Vesnin, Le Corbusier, Alexander Vesnin and Andrey Burov, Moscow 1928

#Viktor Vesnin#Leonid Vesnin#Le Corbusier#Alexander Vesnin#Andrey Burov#Vesnin brothers#constructivism#modernism#Soviet Union#USSR#1928

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vesnin bros. Leningradskaia Pravda, Moscou, 1924.

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

FOMA 22: Workers’ Clubs

This time FOMA presents the construction of Workers’ Clubs in Soviet Russia, narrated by artist and photographer Denis Esakov.

The transition from one culture to another, Kazan. | Photo © Denis Esakov, 2015

The main part of the construction of Workers' Clubs in Soviet Russia was between the end of the 1920s and the mid 1930s. The Bolsheviks who came to power got rid of the symbols of the past and tried to create their own, not similar to the previous ones.

Including due to this, the experiments of the architectural avant-garde artists were supported by the authorities. Up to the time when Stalin changed course and the avant-garde was banned. Clubs were assigned a special role in the interaction of the State and People. Clubs had to form a “new human”. New Soviet Human could not growth in the aesthetics of Tsarist Russia. Therefore, the constructivists solutions were in demand. At the end of the Soviet era, many buildings were rebuilt or abandoned. Changes in culture have left many of these buildings without a goal. Nowadays most of them became shopping malls, office centers, fitness halls, theaters.

Gorky Palace of Culture was the first in Leningrad and the USSR. It was opened on Stachek Square in 1927 (since 1933 - named after M. Gorky) for the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution. It was erected between 1925 and 1927 after plans by the architects A.I. Gegello and D.L. Krichevsky. The Constructivist project with a hall seating 2,200 people and club facilities was awarded the Grand Prix Prize at the World Exhibition of 1937 held in Paris. Now is used as a theater and concert hall.

The Zuev Workers’ Club in Moscow is a prominent work of constructivist architecture. Designed by Ilya Golosov in 1926 and completed in 1928, it housed various facilities to educate and entertain Moscow workers in line with the revolution. The composition of this building is based on the intersection of a cylindrical glazed staircase penetrating a stack of rectangular floor planes behind which are a sequence of club rooms and open foyers leading to a rectangular 850-seat auditorium for theatre performances and assemblies. Part of the extensive glazing has been bricked up and the balconies have been removed in the 1970s, thus lessening the original perforated cubic mass into a more solid box. The building still houses a cultural centre with a children’s theatre and a comic theatre.

The Builders Club was designed and built in the capital of the Ural - Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg) on the order of the builders' trade union. The project was completed by Yakov Kornfeld in 1929 and contains the most vivid ideas of clubs building in the avant-garde style.

The building was completed in 1933. The club building has to participate in the formation of the space of the Paris Commune square. Over the auditorium on a flat roof was a solarium. On the opposite side of the avenue side was simultaneously built a "Chekists Town" - residential houses for NKVD workers. In 1943 film studio was located there. This led to the redevelopment of the building and the changing of the facade. The stylistic unity of the facades and interiors of the building was lost under the reconstruction of the building to the shopping mall in 2002. The walls and ceilings of the rooms was lined with modern materials. Conducted significant redevelopment of indoor spaces.

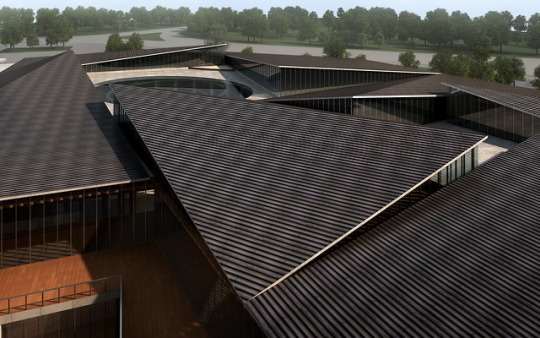

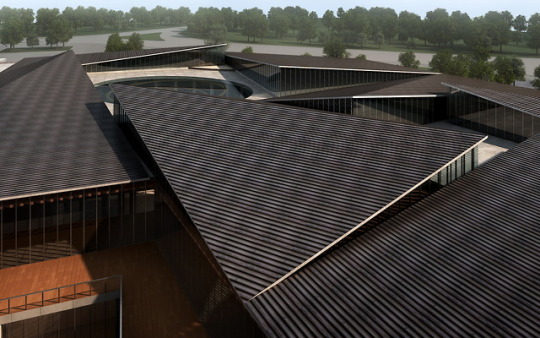

In 1930, a competition was held for the Proletarsky District Palace of Culture, to be built on the site of the demolished Simonov Monastery. After the competition ended with no clear winner, the task was awarded to the Vesnin brothers, who had not taken part in the competition. The architecture that was finally approved can be seen as one of the last, and most voluminous examples of a Constructivist workers’ club.

The Vesnins’ original proposal, influenced by Le Corbusier’s ideas of “flowing spaces”, comprised two buildings – a complex T-shaped public services building with a 1,000 seat theatre hall, large dancing space, a library for 200,000 volumes and winter gardens, and a detached 4,000 seat main theatre. Only the latter did not materialize. The smaller hall was inaugurated in 1933, construction of the public services building dragged until 1937. Unlike other constructivist buildings of the period, “enhanced” by Stalinist façades, the Palace of Culture was completed in precise agreement with the 1930 drafts. After World War II its exterior was, indeed, altered but all the Stalinist additions were stripped in the 1970s. Throughout most of its history, the Likhachev Palace of Culture was operated by the automotive factory ZIL, which is located nearby. Today the building houses the Center of Culture.

Gorbunov Palace of Culture in Moscow was built in 1931-38. in Moscow district Fili at aircraft factory #22. This is the first in Moscow so large Palace of Culture with a diverse indoor use. It reminds Palace of Culture ZIL by Vesnins Brothers in its structure and details.

The Palace was named after the director of the aircraft factory S.P. Gorbunov In 1933 after his death in a plane crash. The building is located on the border with Fili Park of Culture and Leisure. The main facade faces north towards the entrance of the former aircraft factory. On the right is the theater and entertainment part with the auditorium with 1400 seats. The bridge-passage on the second and third floors connects it with the club part. Gym is attached at right angles to the club building. Palace in plan can be seen like an airplane wing from above. Possible this is an allusion to the belonging of a complex to the aircraft factory.Now used as a theater and concert hall.

---

#FOMA 22: Denis Esakov

Denis Esakov is artist and architecture photographer. His works have been published in major architectural media: The Architectural Review, MARK, Archdaily, Dezeen, Wallpaper* and others. Participant of exhibitions in MMOMA (Moscow), Villa Savoye (Poissy, France), the Museum of Architecture. A.V. Shchusev (Moscow), GARAGE Museum (Moscow) etc.

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via The Vesnin brothers' Likachev Palace of Culture (ZIL) in Moscow, 1930-1936)

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

3d building 640 3D Model

Building 640 3D model

High detailed 3d building. Previews were rendered with vray mat and light. The file has all lightning setup and texturing ;multi layer phososhop PSD file included It was at the beginning of the 1920s that the Bauhaus architects permanently distanced themselves from Expressionism and moved closer to "New Objectivity". Two artistic movements influenced this movement: Dutch neoplasticism (De Stijl movement) and Soviet constructivism. The group of neoplasticism gathered in 1917 under the leadership of the painter and poet Theo Van Doesburg, founder of the eponymous magazine of the movement (De Stijl). Van Doesburg and Cornelius Van Eesteren present the neoplasticist ideal, in 1923 in Paris, in the gallery of the "Modern Effort". We can discover a series of projects of houses built according to an asymmetrical arrangement of plans painted with primary colors, which is not without evoking in three dimensions the abstract compositions of the painter Piet Mondrian. This rigorous and abstract approach is fully realized in the Schröder house, built in Utrecht by Gerrit Rietveld in 1924. This house, made of brick and wood for the walls, and concrete for the foundations and balconies, contains an interior space transformable by sliding partitions and possesses another manifestation of modernity. Constructivism, born in Moscow just after the First World War, sees avant-garde artists enthusiastic about the October Revolution and the construction of the new communist society. Due to the economic difficulties of the USSR in the 1920s, most of the constructivist architectural speculations to which the painter Kazimir Malevich contributed, remain in the study phase. The project of a Monument for the Third International, conceived in 1920 by the abstract sculptor Vladimir Tatline, remains the emblem par excellence of the constructivist architecture This work must express the triumph of new technology on traditional masonry construction, as well as the revolutionary momentum of Soviet society. Countless other projects on paper bear witness to the creative effervescence of Soviet architects of the 1920s: the Pravda building in Leningrad, by the Vesnine brothers (1923); skyscraper for Moscow, by El Lissitzky and Stam. Download Building 640 3D model on Flatpyramid now. - #3D_Model #Buildings

0 notes

Text

She only had a short career in art, but for me Popova is one of the most authentic of all Russian Avant Garde artists. Painter, sculptor, designer and costume designer she is multi disciplined , but personally i think the most attractive of all her art is her “Spatial force constructions” . (The Adler catalogue with these works is available through www.ftn-books.com) In theseworks she shines and if you look closely you will find parallels with Morellet and his art and they look far more contemporary than het her other constructivist paintings.

left Popova and on the right Morellet

Popova was born into a wealthy family of Moscow factory owners, which secured her a quality art education. After studying in the studios of Stanislav Zhukovsky and Konstantin Yuon in Moscow from 1907 to 1909, she traveled to Italy, where she was strongly drawn to the monumental art of the early Renaissance. She then traveled to Pskov and Novgorod to study iconography. In 1912 Popova met some of the leading masters of the Moscow avant-garde gathered around Vladimir Tatlin, and for some time she worked at his studio, together with Nadezhda Udaltsova, with whom she was to develop a close friendship, and Aleksandr Vesnin (see Vesnin brothers). Popova, Udaltsova, and Vesnin developed close creative and personal friendships and love that would last throughout Popova’s short lifetime. During this period Popova visited Sergey Shchukin’s renowned collection of French art and, drawn to Cubism, traveled to Paris with Udaltsova. The Académie de la Palette, where Popova and Udaltsova studied Cubism with Henri Le Fauconnier and Jean Metzinger, was to prove a crucial step in Popova’s artistic development.

After another trip to France and Italy in 1914, Popova returned to Moscow as a full-fledged artist, her predilection and interest now centring on Art Nouveau. She organized “weekly gatherings on art” at her house, which attracted the forerunners of the Moscow artistic avant-garde, and participated in avant-garde exhibitions, such as Jack of Diamonds exhibitions of 1914 and 1916, “0.10” (1915), and “The Store” (1916).

The mid-1910s were a turning point for Popova. After successful experiments in Cubism (such as Composition with Figures, 1913), Popova created a series of “plastic paintings,” such as Jug on Table(1915), in which there is a synthesis of painting and relief work using plaster and tin. In 1916 she joined the Supremus Group founded by Kazimir Malevich. Inspired by Malevich’s ideas about abstraction and Suprematism (an art form he invented), Popova developed an individual variation of nonobjective art in which traditional principles were dynamically combined with the flatness and linearity of medieval Russian art and the most innovative avant-garde techniques. She classified her work, with its rhythmical syntheses of coloured planes, as “Painterly Architectonics.”

Popova’s painting gradually began to evolve into Constructivism; her compositions of the early 1920s bear titles such as Construction and Spatial-Force Construction. Thus, her departure from painting and her turn to “practical art” in 1921 was a logical step in her artistic evolution. During this period Popova connected teaching and theoretical work (at, for example, the Moscow Institute of Artistic Culture) while creatively she moved toward the applied arts, working with textile designs, posters, and book covers. Her most interesting work was in the field of set design. She created innovative Constructivist sets around which the action developed. She worked with the Kamerny Theatre of Aleksandr Tairov and Vsevolod Meyerhold. Popova died at the peak of her artistic powers two days after the death of her son, from whom she had contracted scarlet fever.

Lubov Popova (1889-1924) … pure Russian Avant Garde She only had a short career in art, but for me Popova is one of the most authentic of all Russian Avant Garde artists.

0 notes

Text

"The only living Russian architect well-known abroad is a former fantasist"

In the centenary of the Russian Revolution, Alexander Brodsky was the only national architect to offer a response. That says something about Russian architectural culture, suggests Owen Hatherley.

There was a building in London this autumn, by the last Russian architect to have any name recognition whatsoever outside that country. The architect in question is Alexander Brodsky, and the building was a pavilion called 101st km, Further Everywhere.

It was installed in Bloomsbury Square, just outside the long-established Russian cultural centre Pushkin House, who commissioned the project. It was a simple, spindly metal frame, clad in bolted-together felt. You had to clamber under the felt walls, which stopped a couple of feet before the bottom of the frame, to get in.

When you were inside, screens on each side of the walls displayed monochrome footage taken from the front of trains winding through the wastes of Siberia. On the walls, lit by little angled lamps, were printouts of poems by those who had been deported or exiled between 1917 and 1991 (with the exception of the pre-Soviet exile of Alexander Pushkin himself). In the centenary of the Russian Revolution, this was the only response by a major Russian architect. It was bleak, poetic, makeshift, and temporary.

The Soviet Union built a lot, but its architecture began and ended on paper

The Soviet Union built a lot – entire cities in Russia and Ukraine, practically entire countries in Central Asia – but its architecture began and ended on paper. Commemorative exhibitions, like the Design Museum's Imagine Moscow for instance, focused on the remarkable and unbuildable (then, for material reasons, now, for political ones) house-communes, Monuments to the Communist International and Palaces of Labour designed by the likes of Nikolai Ladovsky, Vladimir Tatlin and the Vesnin brothers in the aftermath of 1917.

But when the Soviet Union nosedived from reform to collapse in the second half of the 1980s, its best known designers abroad were the architect Alexander Brodsky – who had served his time working on standardised buildings in the state-run architectural firms – and the artist Ilya Utkin.

Their paper architecture, while equally based on a form of social fantasy, was the reverse in every way from what emerged from the revolution. It was deliberately irrational rather than coldly logical, antiquarian rather than futurist, darkly humorous rather than earnest, pessimistic and dystopian rather than optimistic and utopian, murky and gothic rather than crisp and glassy.

Related story

"Russian architecture is in a transitional state" says architect Yury Grigoryan

Brodsky and Utkin's paper work has just been republished, in the volume Cancelled 6/21/90, which features prints of plates made from zinc stolen from construction sites, which the pair made to be sold individually, and then crossed out. It's even more remarkable to look at these projects nearly three decades years on – they appear to be almost timeless.

The pair's interest in historical architecture could maybe be classed as postmodernist. The pileup of spires and domes across empty space in The Hill With a Hole shows a love of the picturesque and perverse qualities of 19th century eclecticism. The ironic and mournful Museum of Vanished Houses, which collects demolished historical buildings into an imposing, Aldo Rossi-like funereal grid, could be seen as a lament for the destruction of memory and an attack on the placelessness of modern architecture.

Brodsky commented that nothing good came out of the Russian revolution except constructivism

But Brodsky and Utkin didn't do polemic (too Soviet for them, perhaps). Their paper projects could be equally read simply as gorgeously crafted and fascinatingly illogical flights of fancy. Yet, when Brodsky came to making real, three-dimensional new space – as in the Cafe Atrium of 1989 – he first favoured an only partly parodic grotesque classicism that was ideal for the swaggering new rich, a style that has only just gone out of fashion as the house style of Moscow oligarchs. Accordingly, his usually temporary buildings of the last 10 years have tended towards rough, post-industrial and salvaged materials and oblique programmes, which is maybe closer to the gothic vision of the paper architecture.

In a public talk around the time the pavilion was opened, Brodsky commented that nothing good came out of the Russian revolution except constructivism. It's the sort of comment that helps explain why his generation of Russian liberals find themselves out of power. Those who once had free healthcare, full employment and near-free housing, and have experienced the last few decades as a plunge into terrifying poverty and uncertainty, couldn't be expected to agree with him. It also says something about capitalist Russian architectural culture that the only living architect well-known abroad is a former fantasist who only designs small pavilions.

Brodsky's anniversary pavilion seems predicated on the notion that deportation to Siberia began in 1917, when the horrible tragedy of the Russian revolution was people who had once been deported to Siberia under the Tsars meting out the same treatment to their enemies.

However, there's an uncanny power to Brodsky's response to this mostly vacuously remembered anniversary. In a grey London autumn, the wind blows the unpretentiously printed pages of Mandelstam, Shalamov, Tsvataeva et al, and the sound mingles with the rustling of the leaves. In dim November light, in the shadow of the pompously imperial Victoria House, you could almost be in Moscow, in a space that resembles either one of the gimcrack informal pavilions where people sell shawarma or socks, or a train carriage bound for somewhere appalling.

It's rare and important to make monuments to the victims of authoritarianism that are not themselves authoritarian

Inside, the texture of the building, with its untreated materials, showed an interest in surface and material rare in current architecture of any sort. It is put in the service of an unsentimental approach to history that sharply contrasts with the shrill official patriotism that has sharply increased in Russia in recent years.

In that, it's reminiscent of the public memorial project Last Address, where Brodsky has been the designer of a series of plaques placed onto the onetime homes of victims of Stalinist terror. There are many monuments to the victims of Stalinism, and often they're as pompous and nationalistic as the regime they're apparently opposing. Brodsky's plaques are matter of fact and hard, simple letters on a metal panel, with a hole in each where the photo on an ID card or passport might be. Brodsky's apparent belief that revolution only leads to terror is one that is encouraged by the current Russian government, but his memorial work belies that.

It's rare and important to make monuments to the victims of authoritarianism that are not themselves authoritarian.

Owen Hatherley is a critic and author, focusing on architecture, politics and culture. His books include Militant Modernism (2009), A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain (2010), A New Kind of Bleak: Journeys Through Urban Britain (2012) and The Ministry of Nostalgia (2016).

The post "The only living Russian architect well-known abroad is a former fantasist" appeared first on Dezeen.

from ifttt-furniture https://www.dezeen.com/2017/11/29/owen-hatherley-opinion-alexander-brodsky-pushkin-house-pavilion-russian-architect-former-fantasist/

0 notes

Photo

Building the Revolution: Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935

Jean-Louis Cohen

This fascinating book charts the dazzling trajectory of Russian avant-garde architecture during the brief but intense period of design and construction that took place fromc. 1922 to 1935. Fired by the radical new language of Constructivist artists, such architects as Konstantin Melnikov,Moisei Ginsburg and the Vesnin brothers produced designs whose innovative style embodied the energy and optimismof the new Soviet Socialist state. The architectural photographer Richard Pare has spent the last fifteen years documenting the remains and ruins of these iconic structures.His spectacular large-scale photographs are juxtaposed with vintage photographs, contemporary periodicals and numerous drawings and paintings by such Constructivist artists asMalevich, Tatlin, Popova and Lissitsky,making this book essential reading for all who are interested in the history of twentieth-century architecture, Constructivist art and Soviet-era Russia

Cost: $100

Date: 27-May-15

From: NGA Shop

Location: MG Office

ISBN: 978-1-905711-91-8

0 notes

Text

Design Museum's Imagine Moscow exhibition explores six unbuilt Soviet landmarks

Six radical designs for the Moscow skyline – proposed in the wake of the October Revolution, but never built – are showcased in an exhibition opening today at London's Design Museum.

The exhibition Imagine Moscow marks the centenary of the Russian Revolution by dusting off six shelved proposals for architecture in the newly formed Soviet Union, including what would have been the world's tallest skyscraper.

Dating from the 1920s and 1930s, the schemes show the impact of the union's socialist ideology on the work of architects like El Lissitzky and Konstantin Melnikov. Each of the schemes centres around Moscow's Red Square, the city's central plaza.

Drawings, models and projections of the six proposals are presented alongside constructivist and suprematist artworks and designs from the era.

"The October Revoluton and its cultural aftermath represent a heroic moment in architectural and design history," said exhibition curator Eszter Steierhoffer.

"The designs of this period still inspire the work of contemporary architects, and the radical ideas in the exhibition remain highly relevant to cities today.

"Imagine Moscow brings together an unexpected cast of 'phantoms' – architectural monuments of the vanished world of the Soviet Union that survive in spite of never being realised," she added.

Imagine Moscow is on show at theDesign Museum until 4 June 2017. Here's an overview of the six unbuilt projects it features, in roughly chronological order.

Communal House by Nikolay Ladovsky (1919-20)

Ladovsky's Communal House included shared facilities like nurseries and kitchens that aimed to lighten the workload for Soviet women – freeing them up to devote time to self improvement and to work.

The scheme was part of a wider attempt during the period to induce communal housing and amenities that would break down the traditional family unit.

Cloud Iron by El Lissitzky (1923-25)

Lissitzky pitched his network of eight horizontal skyscrapers for Moscow's Boulevard Ring. The top heavy blocks – placed horizontally on top of vertical towers – aimed to maximise a relatively limited footprint.

The horizontal blocks were to contain offices and apartments, which would be linked with metro stations and tram stops at street level by the upright towers.

Lenin Institute by Ivan Leonidov (1927)

A huge sphere would have hosted an auditorium at Leonidov's Lenin Institute, with a slender tower to its rear containing 15 million books split across five reading rooms.

The complex would have also contained a planetarium and science lecture theatres, broadcasting events to the rest of the world by a radio station.

Health Factory by Nikolay Ladovsky (1928-29)

Ladovsky's second project in the exhibition is a design for a retreat on the Black Sea coast, intended to provide respite for weary city dwellers.

Individual rest pods were coupled with communal dining and activity spaces in the scheme, which aimed to improve the productivity of workers on their return to Moscow. Features included a dining hall where food was to be distributed by conveyor belt to do away with the street of queuing.

Commissariat of Heavy Industry proposals by the Vesnin brothers and Konstantin Melnikov (1934-36)

Planned for a vast 10-acre site opposite the Lenin Mausoleum on Red Square, the Commissariat of Heavy Industry could only have been built by demolishing a large chunk of Moscow's old town.

A winning design was never selected for the building, which was intended to celebrate the importance of industry to socialism, but the Design Museum showcases several proposals.

Melnikov's scheme was for a pair of 40-storey buildings linked by an escalator, while the Vesnin brothers suggested four blocks to mirror the towers of the Kremlin.

Palace of the Soviets by Boris Iofan (1931-41)

A 100-metre-tall statue of Lenin mounted on the roof of Iofan's Palace of Soviets would have taken thisbuilding to a height of 516 metres, making it the world's tallest at the time. The city's largest church – the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour – was demolished to make way for the proposal, which was allegedly selected by Josef Stalin himself.

Work began in the mid 1930s but was halted by the German invasion of 1941, and following the second world war Stalin's successor, Nikita Khrushchev, converted its foundations into an open-air swimming pool. A replica of the original cathedral now stands on the site.

Related story

Dead Space and Ruins exhibition questions the future of Soviet architecture

Exhibition photography is by Luke Hayes.

The post Design Museum's Imagine Moscow exhibition explores six unbuilt Soviet landmarks appeared first on Dezeen.

from RSSMix.com Mix ID 8217598 https://www.dezeen.com/2017/03/15/design-museum-imagine-moscow-exhibition-unbuilt-soviet-architecture-el-lissitzky-moscow-russia/

0 notes

Text

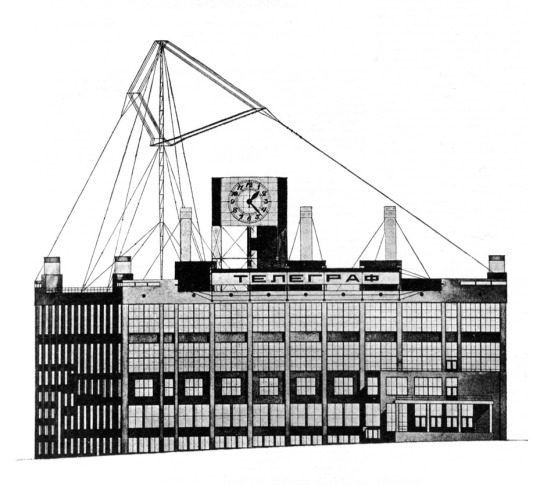

Vesnin Brothers – Central Telegraph Office

1925, Moscow (RU)

Competition entry

via #1

© Sovremennaya arkhitektura 1926/2

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Vesnin brother’s Palace of the Soviets design contest submission (1932).

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Культурный Центр ЗИЛ / ZIL Culture Center

Июнь 2016 / June 2016

9 notes

·

View notes