#totes sus ken

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I wasn't prepared to be a scared young boy

I wasn't prepared to be read like Tolstoy

And destroy

These feelings I feel inside

This war and peace inside my mind

Finding things I shouldn't find

This time they're out to get you

You kinda scare me and I wanna let you

Ken Ashcorp Supernatural

#destiel#deancas#spn#destiel gifs#spn gifs#i dont know how to tag things properly#this is just where i chat bollocks#this song is totes sus though#i mean they said they wrote it about a cartoon but that Tolstoy line & the title?#totes sus ken

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (41): (1587) Sixth Month, Thirteenth Day, Morning.

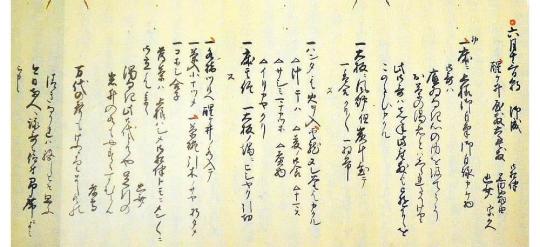

[The entry of this chakai from the Enkaku-ji manuscript of Book Two of the Nampō Roku.]

41) Sixth Month, Thirteenth Day; Morning¹.

◦ O-nari [御成]².

﹆ The six-mat room in the detached [tea] complex at the Same-ga-i [醒ヶ井], [in Kyōto]³.

◦ The Attendants⁴: Kuroda kageyushi [黒田勘解由]⁵, Yūsai [幽齋]⁶, Sōkyū [宗久]⁷.

Sho [初]⁸.

﹆ In the toko, a scroll [featuring] a poem, written and composed, by Lord [Hideyoshi]⁹.

[Hideyoshi’s] verse: soko-i naki kokoro no uchi wo kumete-koso ochanoyu-sha to ha shirare-tari keri [底ゐなき心の内を汲てこそ、お茶の湯者とハしられたりけり]¹⁰.

With respect to this poem, it had been written last year, during [Hideyoshi's] visit to this same room¹¹.

◦ On an ō-ita [大板], the furo; however, only the [unlit] charcoal was placed [in the furo]¹².

◦ Kōgō guri-guri [香合 クリ〰]¹³.

◦ Habōki [羽帚]¹⁴.

Su [ス]¹⁵.

◦ Using a handa [ハンダ], the fire [was brought out from the preparation area and] put into [the furo]¹⁶. [Then] the damp unryū-gama was [brought out and] rested in [the furo]¹⁷.

▵ Shiru hiba [汁 干ハ]¹⁸.

▵ Mugi-no-gohan [麥ノ御食]¹⁹.

▵ Namasu [ナマス]²⁰.

▵ Sashimi mana-katsuo [サシミ マナカツホ]²¹.

▵ Ni-mono [煮物]²².

▵ Iri-kaya ・ kuri [イリカヤ ・ クリ]²³.

[Go [後]²⁴.]

◦ The toko remained as it was²⁵.

◦ On the side of the ō-ita, the hishaku [ヒシヤク], hikkiri [引切]²⁶.

Su [ス].

﹆ Mizusashi tsurube [水指 ツルヘ], with water from the Sanme-ga-i put into it²⁷.

◦ Chaire ko-natsume [茶入 小ナツメ]²⁸.

﹆ Chawan Hikigi-no-saya [茶碗 引木のサヤ], ori-tame [折タメ]²⁹.

◦ Koboshi gōsu [コホシ 合子]³⁰.

[When the service of koicha was finished³¹,] usucha was first [prepared] by Lord [Hideyoshi]; after which each of the attendants took a turn at preparing [a bowl of usucha]³².

Yūsai [offered the following poem]: nigori-naki kono mi-yo tote ya ashi-biki no yuwa-i no mizu mo yasuku-sumuran [濁なき此御代とてや足引の巖井の水もやすくすむらん]³³.

[And] Yoshitaka [孝高]: yorozu-yo no koe mo kyō yori mashi mizu no kiyoki nagare ha taeshitozo mou [万代の聲もけふよりまし水の、清きなかれハ絕しとそ思ふ]³⁴.

On this occasion, immediately after composing their poems, the two people intoned them [for Hideyoshi's enjoyment]³⁵.

_________________________

¹Roku-gatsu jū-san nichi, asa [六月十三日、朝].

The date was July 18, 1587, in the Gregorian calendar. The rainy season generally ends around this time of the year.

²O-nari [御成].

Hideyoshi had returned from Kyūshū, to rest during the spell of intensely hot weather that follows the end of the rainy season.

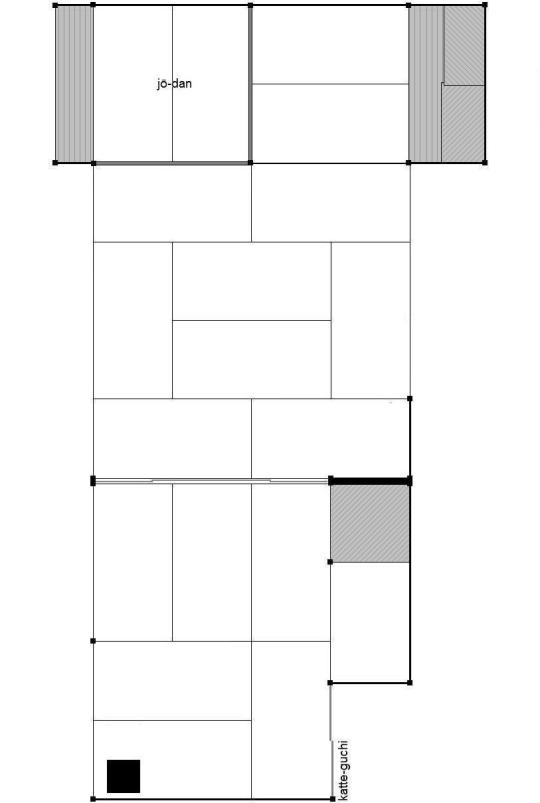

³Same-ga-i yashiki roku-jō-shiki [醒ヶ井屋敷六疊敷].

The Same-ga-i [醒ヶ井] was a well that had been famous for the quality of its water at least since the Heian period*. Also, it is said that this was the well whose water Shukō preferred for chanoyu.

Since the water was popular with those people who practiced chanoyu in Kyōto, a building had been erected in the compound that housed the well†, containing a shoin of perhaps 8-mats (with an additional raised section of four-mats, two of which were on a higher level, serving as a jō-dan [上段], the seat for a nobleman)‡, and a tsugi-no-ma of six-mats (at the bottom of the sketch, which is where the present chakai took place).

Perhaps, since both Hideyoshi and Rikyū preferred a simpler approach to the service of koicha, the six mat room was used for the first part of this chakai; and then (according to notes left by Imai Sōkyū, who was one of the guests) moved on to the shoin for usucha afterward. The location of the ō-ita is shown -- at the bottom left of the sketch. __________ *In the earliest accounts of this well, it is denominated Sameuji-i [佐女牛井], alternately pronounced Samegu-i (the well, or its neighborhood, occasionally figures in poetry). The name was derived from its location (beside the Sameuji-koji [佐女牛小路], which runs east to west). The modern address (the well has long since vanished) is given as Horikawa-gojō [堀川五条] in Kyōto (the well was located near the south-west corner of this major intersection; though at present there is only a memorial stone to mark the spot).

†The compound used for this chakai may have been erected by (or for) Hideyoshi, since, between the late fifteenth century and 1587, the rare mentions of a yashiki in the same compound with the Same-ga-i being used for chanoyu suggest that these tea-related rooms consisted of a 4.5-mat chaseki, a katte, and a mizuya (on the veranda attached to the katte).

‡The actual details of this structure have been lost, beyond what is said in the two documents that address it -- the present kaiki, and the entry in Imai Sōkyū's chanoyu diary. The sketch is based on the layouts of similar tea complexes of this size that are better documented from that period.

See, however, footnote 31 for a discussion of the reliability of Sōkyū's chanoyu diary.

⁴O-shōban [御相伴].

This refers to the other guests who accompany an important person. In addition to being his fellow guests, they also attend upon him, and assist him, when necessary, throughout the gathering.

⁵Kuroda kageyushi [黒田勘解由].

This was Kuroda Yoshitaka [黒田孝高; 1546 ~ 1604], an important daimyō, who first served Oda Nobunaga. Later he was a major strategist and adviser of Hideyoshi (joining Hideyoshi's camp for the battle of Yamazaki)*. He is better known to Westerners (especially in the context of chanoyu studies) as Kuroda Josui [黒田如水] -- from the name he used during his retirement, Josui-ken [如水軒]†.

Yoshitaka was also (albeit briefly) a convert to Christianity†, in which context he was known as Dom Simeão (Don Simeon [ドン・シメオン])‡. His retirement from public life was in response to Hideyoshi's expulsion edict against the Christians -- which (in a parallel case to that of Hosokawa Yūsai) did not completely debar him from participation in certain aspects of public life. __________ *It has been suggested that part of the reason for Hideyoshi's fear of Kuroda Yoshitaka was precisely because of the latter's intelligence and acumen in military matters -- though Yoshitaka seems to have tried to downplay his abilities -- and, specifically, to Hideyoshi's debt to Yoshitaka regarding the victory at Yamazaki. (According to some scholars, Hideyoshi feared that, if Yoshitaka ever turned into an enemy, he would use his abilities to overthrow Hideyoshi. Hideyoshi's unease was further exacerbated by Yoshitaka's closeness to Sen no Rikyū -- and his resulting opposition to the invasion of Korea, which was intended only to lift Hideyoshi onto the Chinese throne.)

†The only way to “officially” retire from the consequences of ones position was to shave ones head and (at least nominally) take Buddhist orders -- become nyūdō [入道] (then as now there were sympathetic monks who would be willing to accept an honorarium without demanding that the candidate do more than cut off his hair and simplify his style of dress). Going through the form would have had no real impact on his Christian faith; it just freed him from his responsibilities to Hideyoshi, and to his position. (In the same way, Hosokawa Fujitaka was able to avoid having to side with Akechi Mitsuhide -- whose son and heir was married to Fujitaka's son -- in the aftermath of Mitsuhide's treachery, as the norms of the period fully dictated he had to do, by shaving his head and becoming nyūdō.)

Kuroda Yoshitaka retired in 1587 (and, perhaps for the “second time,” in 1589); his full Budhist name (hō-myō [法名]) was Josui Ensei [如水圓清]. It is said that Josui may have been chosen because the pronunciation was similar to Josué (the Portuguese form of Joshua), in the same way that another Christian daimyō of his time, Naitō Tadatoshi [内藤 忠俊; ? ~ 1626] took the name Jo-an [如安] because of the similarity to the Portuguese name João.

‡His decision to convert seems to have been the result of his observations of the honorable behavior of the Christian community in Kyūshū during the recent campaign.

⁶Yūsai [幽齋].

This was the (former) daimyō and literary scholar Hosokawa Fujitaka [細川藤孝; 1534 ~ 1610], who was known as Hosokawa Yūsai [細川幽齋] after his “retirement” from secular life following Akechi Mitsuhide's attack on Nobunaga at the Honnō-ji in Kyōto*. Fujitaka was originally a champion of the Ashikaga shōgunate, though he later offering his allegiance to Oda Nobunaga; and, subsequently, to Hideyoshi (as Nobunaga’s successor)†.

As a literary scholar Hosokawa Fujitaka’s fame is well known. He was also an intimate colleague -- and friend -- during Rikyū’s years of service to Hideyoshi‡. ___________ *After Nobunaga’s seppuku, rather than join Akechi Mitsuhide (to whose daughter Fujitaka’s son was married) as custom demanded, Hosokawa Fujitaka decided to shave his head and became nyūdō [入道], taking the name Yūsai on this occasion. (With this act, he surrendered his status as a daimyō to his son -- who was under no obigation to do anything, with respect to Mitsuhide and his plot.)

†Hosokawa Fujitaka’s refusal to participate in the battle of Yamazaki probably helped to secure the victory for Hideyoshi. As a result, though Fujitaka was technically retired, he remained active both as a political and cultural advisor to Hideyoshi to the end of his life (for which Hideyoshi rewarded Fujitaka with an income and land in Yamashiro Province in 1586, which he doubled in 1595).

Nevertheless, Fujitaka supported Tokugawa Ieyasu (perhaps due to a personal dislike for Ishida Mitsunari and his schemes, which resulted in the death of Fujitaka’s son’s wife and granddaughter), for which the family was honored by the Tokugawa bakufu.

‡Which support persisted even after Rikyū’s death: the reason why it was his son who went to the bank of the Yodo River to “see Rikyū off” (when he was sent back to Sakai to await his death sentence) was not because of a lack of affection, but so that Fujitaka would be in a position to ward off any attacks (on both Rikyū, and Fujitaka’s own family) from Hideyoshi which this gesture of esteem may have precipitated.

⁷Sōkyū [宗久].

This was Imai Sōkyū [今井宗久; 1520 ~ 1593], who was said to be “the other one” of Jōō’s two outstanding disciples*.

Sōkyū was married to Jōō’s daughter, and assumed the guardianship of Jōō’s son Sōga [宗瓦; 1550-1614] (who was just six years of age at the time of his father’s death).

At the time of this chakai, the relations between Sōkyū and Rikyū were still more or less cordial, with the main source of conflict between them being competition for Hideyoshi's favor†. ___________ *The first was, or course, Rikyū.

†The primary cause of the bad blood between Rikyū and Sōkyū seems to have arisen because Rikyū disagreed with Sōkyū over how he was managing Sōga’s (Jōō’s son) affairs.

Sōkyū seems to have taken charge of Jōō’s extensive collection of meibutsu utensils shortly after Jōō’s death, which he said was intended both to safeguard them (as Sōga’s inheritance), as well as (in certain cases) reimburse himself for the added expenses placed on his household by the boy’s upbringing. Rikyū, meanwhile, believed (and made it publicly known) that, in his opinion, Sōkyū was simply enriching himself -- both monetarily and with respect to his reputation as a tea master -- at the boy’s expense. (It must be remembered, with respect to meibutsu utensils, that ownership implied that the owner also had been initiated into the secrets of their use -- and, indeed, it was just this fact on which not only Jōō’s own reputation, but eventually that of Sōkyū as well, had been based.)

Rikyū’s own densho addressed to Sōga, meanwhile, suggests that, in his opinion at least, Sōkyū was not doing a very good job at educating the young man in the details of chanoyu that had been handed down by Jōō, but rather was schooling him in Sōkyū’s own version of the practice (which seems to have remained faithful to the style of chanoyu popularized by Jōō during his middle period) . Sōkyū’s way of practicing chanoyu (as the leader of the machi-shū faction that was increasingly opposed to Rikyū’s simplifications) can be identified with what is now called the machi-shū style of tea -- which passed into the modern world through Sōtan and his descendants. The difference between Sōkyū’s “machi-shū style” and Rikyū’s chanoyu can be seen clearly by comparing Rikyū’s densho with the modern Senke version of chanoyu.

After Rikyū’s death, Sōkyū was one of the leaders of the group that sought to eradicate all traces of Rikyū’s teachings from the practice of chanoyu -- and, given the subsequent and lingering animosity between the Sen families and Rikyū’s own writings, we might say that Sōkyū was more successful in leaving his stamp on chanoyu than he could ever have dreamed possible.

⁸Sho [初].

The shoza.

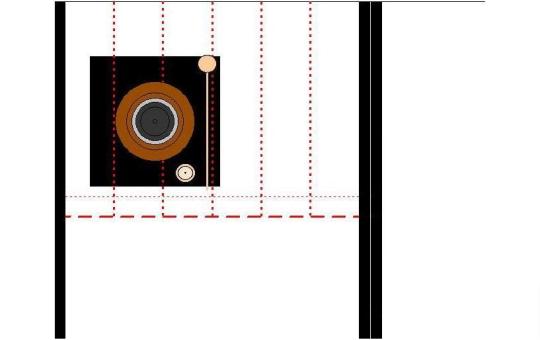

With respect to kane-wari:

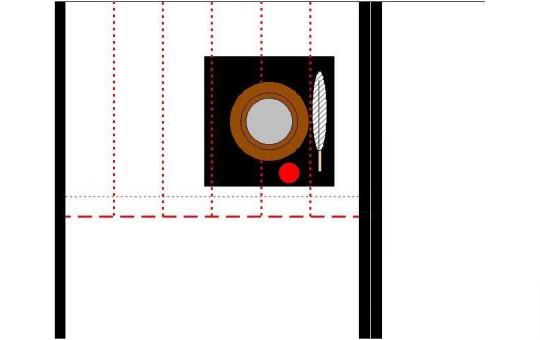

- the toko held only a kakemono (of one of Hideyoshi's waka-kaishi [和歌懐紙]), and so was han [半];

- the room had the furo, resting on an ō-ita, along with the kōgō and habōki (as shown above)*: however, since the kōgō and habōki did not contact any of the kane, the ō-ita furo, and therefore the room itself, counted as han [半].

Han + han is chō, which is appropriate for the shoza of a chakai held during the daytime. __________ *I have shown the ō-ita on the left side of the utensil mat because it seems that Hideyoshi strongly objected to its being placed on the right (since the furo tended to obscure his view of what the host was doing).

After the destruction of the Ishiyama Hongan-ji (and the subsequent appropriation of the site for Hideyoshi’s Ōsaka castle), Hideyoshi became perennially fearful that secret followers of that sect (which seems to have included most -- if not all -- of the Sakai chajin) might attempt to assassinate him (one of this radical sect’s preferred methods of eliminating their opponents apparently included the use of poison). He, therefore, remained fearful of poison to the end of his life.

If the furo is placed on the right, however, the arrangement would be as shown below.

In this case, the habōki and kōgō would have been placed on the right side of the furo, as shown. The considerations related to kane-wari would be the same as described above, in the body of this footnote.

When the room had a tsuri-dana attached to the outer wall, there was no help but to put the furo on the right side of the mat (though at least some of the machi-shū started placing the furo on the left -- albeit moving it a little closer to the center of the mat so that the mouth of the kama, at least, was not under the tana -- and this practice has been perpetuated by some of the modern schools). And while the same orientation was also supposed to apply when the room had a dōko (when taking things out of the dōko, they were not supposed to be moved across the front of the furo, for fear of causing inadvertent damage), it is possible that the objections had less force with Hideyoshi in this setting, and the furo may have been placed on the left (in which case the host may have limited the number of things placed in the dōko -- such as by arranging the mizusashi and chawan and chaire on the mat, rather than keeping them in the dōko until needed as was originally the case.) This is also the reason why most modern schools are generally unsure about how to use the dōko.

Ultimately, Hideyoshi’s objection is the reason why, even today, the modern schools continue to teach that the furo should be placed on the left side of the utensil mat.

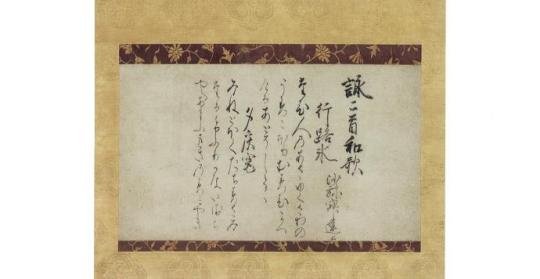

⁹Toko ni ue-sama o-ji-hitsu o-ji-ei kakemono [床ニ 上樣御自筆御自詠カケ物].

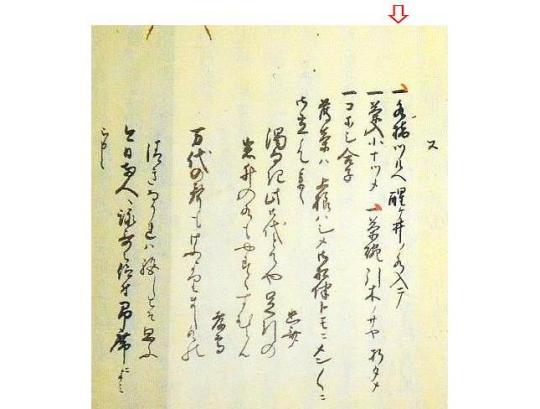

This means that the scroll that was displayed in the tokonoma consisted of a waka-kaishi [和歌懐紙]*, the verse having been both composed (ji-ei [自詠]), and written (ji-hitsu [自筆]), by Hideyoshi during a visit to the Same-ga-i the year before.

This scroll is not known today. __________ *The reader should not confuse kaishi [懐紙], as used here, with the small packet of paper that is used in chanoyu when eating kashi, and so forth. Kaishi, here, refers to something much larger (perhaps similar to the packet of folded paper used as a kami-kamashiki [紙釜敷] today -- though generally folded only in half, not into quarters as is done when the pack of paper will be used as a kamashiki).

Kaishi was originally a sort of note paper that persons of the higher classes carried on their person, on which letters (or poems) were written -- the practice dates at least to the Heian period (when the frequent exchange of written messages was an ordinary part of the daily life of the upper classes).

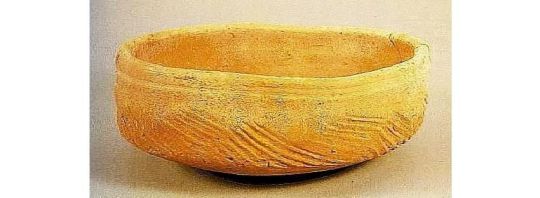

A hanging scroll made from a waka-kaishi is shown above. (Note this is not the scroll that was displayed at this chakai, though the kakemono may have looked similar to this example.)

¹⁰O-uta, soko-i naki kokoro no uchi wo kumete koso o-chanoyu-sha to ha shirare-tari keri [御歌、底ゐなき心の内を汲てこそお茶の湯者とハしられたりけり].

O-uta [御歌] means “the honorable poem.” In other words, Hideyoshi’s poem, the verse inscribed on the kaishi that was mounted as the kakemono.

Hideyoshi's verse may be translated “dipping out [water] from within the mind that has no ulterior motive: this is how the [true] chanoyu-sha can be known.”

Soko-i [底意]* means an underlying (or ulterior) motive; ones true (or secret) intention. Soko-i naki [底意なき] means to have no ulterior motive. Therefore, soko-i naki kokoro no uchi [底意なき心の内] means (from) within the heart that has no ulterior motive (in pursuing the practice of chanoyu).

Kumete-koso [汲てこそ] means if we can dip out [water] in this way. In other words, perform the action of using the hishaku mindlessly. Perhaps, rather than to the specific act of dipping water with the hishaku, Hideyoshi is thinking of the actions performed during the temae more generally.

Ochanoyu-sha to ha [お茶の湯者とは] means "and as for (someone who is regarded as) a chanoyu-sha†..."

Shiraretari-keri [知られたりけり] means “(such a one) can surely be understood (or recognized) in that way.” __________ *In some versions, “soko-[w]i” [底ゐ] is written as “soko-hi” [底ひ]. Both forms would (in this example) be pronounced soko-i in the modern language.

†Essentially, a chanoyu-sha is someone who has dedicated their life to the practice of chanoyu, and it is probably in this sense that Hideyoshi has used the word in his poem.

In the Yamanoue Sōji Ki [山上宗二記], Sōji elaborates on the distinctions between a wabi-suki-sha [ワビ数奇者], a chanoyu-sha [茶湯者], and a mei-jin [名人]. While an absolute dedication to chanoyu is the commonality between the three, the possession of meibutsu utensils, (commercial) “professionalism,” and an (acknowledged) ability to influence ones milieu -- or lack whereof -- seem to be the determining factors, “in Sōji’s view.” That said, the work is suspect precisely because it emphasizes exactly these qualities that the Tokugawa bakufu wished to highlight in their version of chanoyu (as a way to beggar the daimyō and merchants, so that neither would be able to finance a rebellion against Tokugawa rule: this is what chanoyu became under the Tokugawa, and it is the shame under which the practice labors today -- the foolish focus on utensils and fictitious rank based on “secrets” that has brought about the demise of chanoyu among the modern-day Japanese).

¹¹Kono o-uta ha, sen-nen kono zashiki ni te asobashiku-dasare wo, kono-tabi kakuru [此御歌ハ、先年此座敷ニて被遊下候を、このたひカクル].

Here Rikyū explains the circumstances under which Hideyoshi’s poem was composed -- that it had been composed during Hideyoshi’s visit to the Same-ga-i the previous year.

¹²Ō-ita ni furo, tadashi sumi bakari okite [大板ニ風爐、但炭斗置テ].

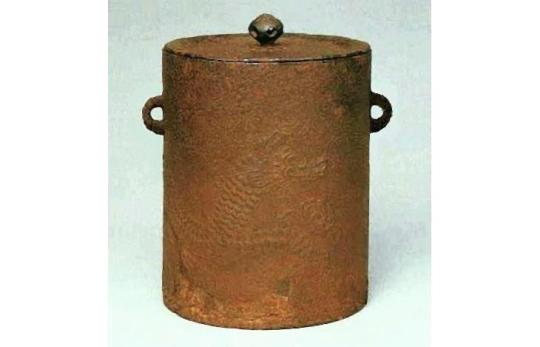

The furo seems to have been the small bronze Chōsen-buro [朝鮮風爐] that had belonged to Jōō (which is shown below)*, which Rikyū probably chose because it would minimize the sight of the burning charcoal throughout the gathering.

Furthermore, since with the end of the rainy season, the weather becomes hot and muggy, Rikyū also decided to arrange the charcoal in the furo ahead of time -- but left the fire (and the kama) out. The sight of the slightly damp†, black charcoal, would have been visually refreshing -- as well as importantly doing nothing to increase the ambient temperature in the room. __________ *Though Rikyū says nothing (all that can be deduced from his kaiki is that this was a small furo -- since that is the only kind that could be used on an ō-ita); but Imai Sōkyū notes that it was a bronze furo (dō-buro [銅フロ] -- dō [銅] meaning copper or brown-colored bronze), this was probably the Chōsen-buro that Rikyū had used during the chakai held on the 13th of the Fourth Month. On that occasion, the kama was also the small unryū-gama, as it was here.

†The charcoal for chanoyu should be washed with water the day before, to remove any dust (since the dust can explode, and send red-hot sparks shooting out of the furo or ro, which can burn the tatami). It is then put in a shady place to dry. However, it is (and should be) still a little damp by the next day; and it is the evaporation of this moisture that actually helps the charcoal to light faster, since the rising moisture pulls fresh air into the center of the fire.

This is especially important in the case of the furo, since the ash in the furo is dry.

In the case of the ro, the shimeshi-bai [湿し灰] itself is also damp; however, the larger fire that is built in the ro makes good air flow extremely important, especially when the fire is first put into the cold ro at dawn (carbon dioxide, being heavier than air, tends to settle to the bottom of the ro as it cools overnight, so it is critical to establish a good air flow at the very beginning, otherwise the lingering carbon dioxide will extinguish the embers before the charcoal can catch). Since, traditionally, the fukube was filled with the whole day's supply of charcoal, the charcoal would continue to dry out over the course of the day, balancing the decreased evaporation with the existing heat in the ro.

¹³Kōgō guri-guri [香合 クリ〰].

This was Rikyū's lacquered kōgō: it was said to have originally been part of Ashikaga Yoshimasa's Higashiyama collection.

¹⁴Habōki [羽帚].

This would have been a habōki made from feathers that were between 9-sun and 1-shaku in length -- the kind of habōki that are most commonly seen today.

It is not possible to say what kind of feathers were used -- though, given the setting, they would have been the most beautiful and interesting feathers available. (While ordinary habōki were usually used only once, habōki made from rare and precious feathers were often preserved, and used again on those rare occasions when such habōki would be appropriate.)

¹⁵Su [ス].

Su [ス], which Tachibana Jitsuzan uses consistently in his version of this kaiki*, actually suggests the kanji mata [又], meaning “and again.”

The meaning is that the utensils that follow were not displayed in the room. They were brought out from the katte at the beginning of the temae. ___________ *In his original copy of the kaiki (which was made with the original Shū-un-an documents in front of him), the kanji mata [又] actually occurs much more frequently. The decision to convert all of the instances where this kanji is used to the katakana su [ス] was, therefore, done for some specific reason -- which, however, Jitsuzan never elaborated upon. (It is speculated that he may have wished to make the text seem more mysterious than it actually is.)

¹⁶Handa ni te hi wo irete [ハンタニて火ヲ入].

Handa [半田]* literally means tin or lead solder, and seems to have been a slang term for a sort of small earthenware vessel in which solder was melted (this is the only occasion where Rikyū uses this word of which I am aware). Imai Sōkyū's version uses the word handa-donabe [半田土鍋], which literally means a shallow earthenware pot in which solder was melted. In his other writings, Rikyū usually uses the word hōroku [炮烙], which means a similarly-shaped earthenware vessel (albeit one used in the kitchen for baking -- as in a system resembling a “Dutch oven,” where a second inverted hōroku is placed over the hōroku containing the food that is to be baked -- or parching food).

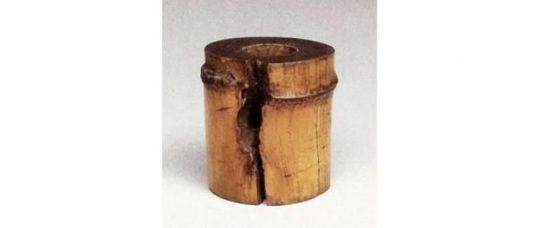

Rikyū's hōroku (the surviving example was made for him by Chōjirō) is shown above. It is 7-sun in diameter, and so a little larger than the modern haiki (the shape of which are usually copied from it).

The hōroku was filled about half way full with shimeshi-bai [湿し灰]†, and after the ash was leveled, three burning gitchō were stood on top, and so carried out into the room (with a pair of hibashi resting across the rim of the hōroku, with which the charcoal was moved into the furo). __________ *The kanji used for this word are hentai-gana. They have no literal meaning.

†Shimeshi-bai [湿し灰] means damp ash.

According to Rikyū's densho, ordinary ash is dampened with clean water until it forms a rather hard, brick-like mass. After allowing the ash to sit for a while (so that excess water will be lost), it is placed in a (special heavy paper) sack that was used for boiling medicinal herbs, and the sack was then struck forcefully against a board, causing the ash to fragment into a mixture of small pieces of various sizes. It was used as it was (with only any large pieces picked out). According to Rikyū, the shimeshi-bai was prepared just before it would be used.

This is very different from the way the modern schools teach to prepare shimeshi-bai.

¹⁷Unryū nure-gama ni te kakuru [雲龍ヌレ釜ニてカクル].

When Hideyoshi and the other guests entered for the shoza, they found a furo resting on the ō-ita, containing a full set of charcoal (but with an open space in the middle of the arrangement). Rather than performing a sumi-temae, after the usual exchange of greetings, Rikyū brought out a hōroku containing three burning pieces of charcoal. After dusting the furo with the habōki, he moved the hōroku in front of the furo, and lifted the three pieces of charcoal into the center of the charcoal arrangement. Then, after dusting the furo again, he placed the incense onto the charcoal.

He returned the hōroku to the katte, and came back carrying the (wet) small unryū-gama, and rested it on the gotoku that was arranged in the furo.

This was the second small unryū-gama, which had “matsu-gasa” kan-tsuki* and an iron lid. So the lid would have been dampened as well.

After placing the kama in the furo, Rikyū would have dusted the rim and shoulder of the furo again (the lid of the kama would have still been wet), and then used the habōki to dust the utensil mat, from the front of the ō-ita to its lower end, while the guests inspected the kōgō. ___________ *Far from resembling pine-cones (as the name suggests), they are semi-circles, albeit with a scale-like pattern (and probably intended -- the original kan-tsuki featuring this kind of design are seen on a Korean kama and bronze furo that was owned by the Hosokawa family -- to suggest coils of a dragon, or some such motif).

¹⁸Shiru hiba [汁 干ハ].

Hiba [干葉] are the dried leaves of the daikon*. The dried leaves are reconstituted by soaking in water, and then cut into pieces before being put into the soup.

The soup was miso-shiru. __________ *Daikon is traditionally sold (in the wet market) with the leaves intact -- since the dark green and crispness of the leaves indicates that the root was freshly dug (the leaves wilt and then begin to turn yellow after a day or so; and as they wither, they draw water out of the root, making it tough). The leaves are generally lopped off in the market, so the customer will not have to deal with the waste at home.

Since the wet markets generally closed around noon, poor people would often come by to collect these leaves, which they took home and dried (by draping them over a clothes line strung up across the kitchen garden, with the crown above and the leaves dangling below). This also helped the market stall with clean-up.

Like many other things (such as dengaku, and mugi-meshi [麥飯] -- see the next footnote), what was originally the province of the very poor had now, rather perversely, become a sort of delicacy savored by the upper classes.

¹⁹Mugi no gohan [麥ノ御食].

Mugi-meshi [麥飯]* means white rice that is mixed with a certain amount of barley (mugi [麥]) before the grains are steamed.

As mentioned in the the commentary that accompanied the translation of the previous gathering, barley was usually planted around the end of the year (since it grows best when the temperature of the soil is around 0° C); thus the barley harvest would have been taking place around the time of this chakai, so Rikyū may have decided to serve mugi-no-gohan as a sort of seasonal delicacy†. __________ *This word can also be pronounced baku-han [ばくはん = 麥飯], and mugi-ii [むぎいい = 麥飯].

†The Japanese also seem to believe that barley is good for the body during hot weather. This is still seen today, when iced barley tea (mugi-cha [麥茶]) -- with a touch of salt (to help the body replace what is lost through persipration) -- is hugely popular during the post-rainy-season heat wave.

²⁰Namasu [ナマス].

This is a sort of salad, usually made from julienned daikon and carrot, dressed with a mixture of rice vinegar, sake, mirin, and soy sauce.

²¹Sashimi mana-katsuo [サシミ マナカツホ].

Mana-katsuo [真名鰹] (shown below) is a distant relative of the katsuo [鰹]. This fish has white flesh (whereas katsuo is pink to red in color), and is very oily. Accordingly, while delicious, people are generally cautioned not to eat too much of it, or it can cause digestive problems.

The sashimi would likely have been served with iri-zake [煎り酒]* as a dipping sauce -- though it is also possible that a shallow dish of precious soy sauce might have been offered to Hideyoshi. __________ *Iri-zake [煎り酒] is a sort of dipping sauce prepared from “old” sake (the “dregs” of the sake-cask, which had lost a lot of its alcohol through evaporation -- which occurs each time the cask is opened).

First, a piece of dashi-kombu is soaked in the room-temperature sake for several hours (to deepen the taste), then removed. Then several ume-boshi are placed in the sake, and the sake is brought to a boil. After about 5 minutes, a large handful of katsuo-bushi is thrown in to the sake, and it is allowed to continue simmering until the volume is reduced by half. Then (as when making dashi) the pot is removed from the heat and allowed to cool for five minutes while the katsu-bushi settle (waiting too long will result in too strong a taste). Then the clear liquid is decanted off (and filtered through a piece of sarashi).

This is the iri-zake, and it was used as a dipping sauce after it was fully cooled.

²²Ni-mono [煮物].

Ni-mono means foods cooked (and usually -- though not always -- served) in clear broth. Unfortunately, Rikyū does not mention what the ingredients were, or how they were served.

Rikyū seems to be making an effort to keep the meal as light as possible, on account of the heat (since overeating on a hot day would make the guests feel lethargic).

²³Iri-kaya ・ kuri [イリカヤ ・ クリ].

These were the kashi.

Iri-kaya [煎り榧] are the roasted nuts of the Japanese allspice tree (also sometimes called the Japanese nutmeg yew -- Torreya nucifera).

And kuri [栗] probably refers to yaki-guri [焼き栗], chestnuts roasted over charcoal.

²⁴This word is not found in the Enkaku-ji version of the text. Go [後] (meaning the goza), however, is implied by the listing of the utensils, which follow.

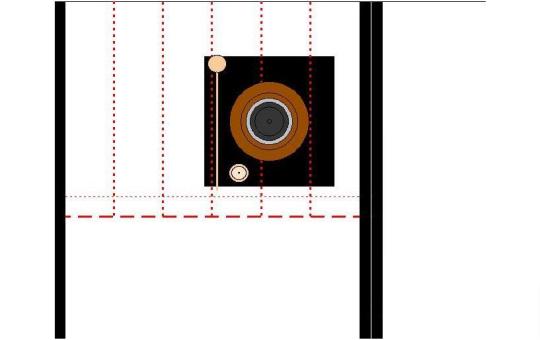

As for the kane-wari:

- the scroll continued to occupy the toko by itself, meaning the toko remained han [半];

- meanwhile the room had only the ō-ita furo*: though, in addition to the kama-furo, the hishaku and futaoki were also arranged on the ō-ita (with the latter two utensils arranged on the opposite side of the furo from where the kōgō and habōki had been placed, meaning that the cup of the hishaku came into contact with the central kane) -- whereby the ō-ita, and so the room, was counted as chō [調].

Han + chō is han, which is correct for the goza of a chakai held during the daytime. __________ *As explained above, in the sub-note under footnote 8, the furo was probably placed on the left side of the utensil mat, as shown above, because Hideyoshi preferred things to be done in that way. The orthodox arrangement, however, is shown below.

In this case, the hishaku and futaoki are placed on the left side of the furo, with the hishaku (still) contacting the central kane.

The details of the kane-wari remain the same.

²⁵Toko sono-mama [床 其儘].

That is, the scroll remained hanging by itself in the toko, just as during the shoza.

²⁶Ō-ita no hashi ni hishaku ・ hikkiri [大板ノ端ニヒシヤク ・ 引切].

The hishaku and futaoki were arranged on the ō-ita together with the furo, with the handle of the hishaku parallel to the side of the ita closest to the center of the mat.

The futaoki was one of Rikyū’s take-wa [竹輪] (the word hikkiri [引切] was probably added by Tachibana Jitsuzan, since this was the word preferred by chanoyu practitioners who were members of the samurai caste).

²⁷Mizusashi tsurube, Same-ga-i no mizu irete [水指ツルベ、醒ヶ井ノ水入テ].

The mizusashi was a kiji-tsurube.

It contained water that had been drawn from the Same-ga-i that dawn.

Traditionally, the kiji-tsurube was sealed by passing a paper tape through the hole in the crossbar (the “handle,” by means of which a pair of tsurube were suspended from ropes tied to opposite ends of a shoulder-pole, for transport to the mizuya), which then circled the body of the tsurube, with the two ends pasted together on the side that would face the guests (the side with the movable lid). This was to “guarantee” that the water, drawn at dawn, had not been tampered with. Before the tsurube could be opened, the tape had to be cut off with a small knife. However, since Hideyoshi is known to have objected to the presence of even this small blade in the tearoom, Rikyū probably removed the tape in the katte (if one was even applied to the tsurube -- which would have been guarded in the katte by two of Hideyoshi’s personal bodyguards, along with the food and all of the other utensils -- on this kind of occasion).

The kiji-tsurube was not brought out from the katte until the beginning of the koicha-temae. (While in the small room, the host should keep his comings and goings to a minimum, in a large room -- the room was of 6 mats -- carrying out the various utensils in an elegant manner before the eyes of the guests was an important part of the atmosphere.)

When the kiji-tsurube is used, the rule is that the host should walk onto the utensil mat* bearing the tsurube, squatting down in front of the space where it will be placed, and so lowers it to the mat directly (without moving it around once it has come into contact with the surface of the tatami). Then, at the conclusion of the temae, the tsurube should be left in situ until after the guests have left. These things were done because the bottom of the kiji-tsurube was usually wet (due to water seeping through the wood), and so inclined to leave unsightly marks on the mat if it was moved away from a spot†.

Since the kiji-tsurube was not displayed on the utensil mat from the first, as was the usual way of doing things, the fact that it was kept under guard in the katte likely explains why it was not brought out (without a sealing tape) until the beginning of the koicha-temae. In the Enkaku-ji version (shown above), this entry is marked with a red spot, indicating its importance (likely also emphasizing the reason why it was not brought out until later -- this mark can be seen at the beginning of the thirteenth line from the left, which I have indicated by an arrow above the line in the original document**). ___________ *The ancient rule was actually that neither host, nor guests, should ever walk (or stand) on the utensil mat.

In the case of other kinds of mizusashi, the host walked into the room and then sat down at the lower end of the utensil mat (placing the mizusashi down forward of his knee, on the side of the mat adjacent to the wall), and moved forward to the temae-za on his knees (advancing the mizusashi forward in front of himself in steps).

However, because the kiji-tsurube was wet, an exception to this rule was made because the correct way of doing things was not possible (since it would leave a water mark each time it was set down, making the mat look messy).

Sōtan used only a kiji-tsurube as his mizusashi for most of his life. Thus, when he was suddenly called upon to use something else (when he made tea for the imperial consort Tōfukumon-in and her court -- at which time he was in his 50s), he, out of habit, handled the mizusashi in the same way as he had done when using a kiji-tsurube -- since he forgotten (if he had ever known) that there was this point of difference. This (like much else) is where the modern way of doing things originated.

†Modern kiji-tsurube are generally sealed, on the inside, with silicon sealing-compound, so they will not leak. While lacquer and pitch were both available in Rikyū’s day (which would have given excellent results), using them to seal the tsurube was considered impure. Therefore, the kiji-tsurube was held together only with the pressure of the iron nails with which it was held together; for which reason it almost always leaked, at least to a certain extent. Inadvertence, therefore, dictated this special dispensation from observing the rules.

**The entire entry, from the Enkaku-ji manuscript, is shown at the beginning of this post. Here I have focused in on the final part of the kaiki, following the second “su” [ス]. The line in question reads: ﹆ hitotsu mizusashi tsurube same-ga-i mizu irete [一 水指ツルヘ醒ヶ井ノ水入テ] (where “﹆ “ is the notation that I have been using for the red spot that was used -- presumably by Rikyū, according to Jitsuzan -- to indicate the special features of a chakai; hitotsu [一], which means “one” indicates each individual part of the entry, which I have indicated by a small circle “◦” in my translations).

²⁸Chaire ko-natsume [茶入 小ナツメ].

This was a plain, black-lacquered ko-natsume.

It was most likely tied in a shifuku.

²⁹Chawan Hikigi-no-saya ・ ori-tame [茶碗 引木のサヤ ・ 折タメ].

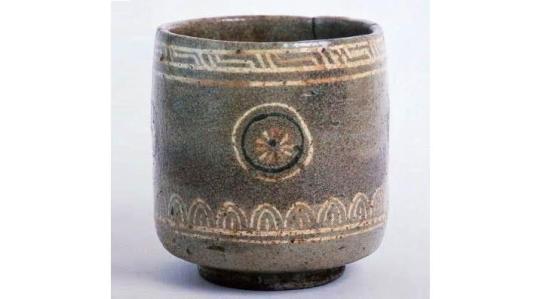

This is a (low quality) Korean celadon tsutsu-chawan*, with the type sometimes referred to as kyōgen-bakama [狂言袴]† in Japan.

While it seems strange (to us) that a deep chawan would be used at the beginning of the hot weather that follows the end of the rainy season, this kind of bowl actually allowed Rikyū to make the tea cooler than usual‡, the deep bowl preventing the koicha from cooling further (to the point where the tea would become too thick to drink).

The chashaku -- an ori-tame [折撓] made by Rikyū -- was rested atop the chawan, with the chakin and chasen were arranged inside it, as usual.

__________ *In the kaiki that makes up Book Two of the Nampō Roku, as Tachibana Jitsuzan wrote it, Rikyū sometimes refers to this chawan by its name (Hikigi-no-saya [引木の鞘]), and sometimes descriptively (as the Mishima zutsu [三嶋筒]).

The early “Mishima” pieces, and Korean celadons, were fired at the same kilns, and fabricated from the same clay and glaze. The only difference between them is the color the glaze assumed during firing (when the glaze was blue or green, the piece was called celadon, and was considered to be of higher quality; when the glaze came out a milky-gray, or was almost colorless, the pieces were judged to be of lower quality -- and this was the pottery that came to be referred to as “Mishima” in Japan).

†Kyōgen-bakama [狂言袴] means the kind of pleated skirt worn by the performers of kyōgen [狂言]. Similar to the nō [能] drama (and usually included -- as “comic interludes” -- in the same program), kyōgen were lighter, humorous pieces (the word kyōgen literally means “crazy talking”); and they were generally not performed in costume.

The round circular designs and decorated borders of this type of bowl resemble the crests that adorned the kyōgen players’ hakama.

‡By this point in the year, the tea leaves (which had been harvested and processed the year before) will have become very weak: thus, the water used to prepare the koicha must be as cool as possible. Using a deep chawan prevents the already (relatively) “cool” tea from cooling further, helping to insure that the guests can drink the tea precisely as the host made it.

³⁰Koboshi gōsu [コホシ 合子].

A gōsu [合子 -- originally written 盒子] is a kind of lidded bowl in which offerings of rice or water were made to the Ancestors in Korean jesa [제사 = 祭祀] ceremonies. In the early days, only perfect sets of utensils could be used for these ceremonies; and if one piece was lost or damaged, the entire set was melted down and recast. However, occasionally, when these were pieces of especial quality (such as utensils from sets made for use by the king’s family), the court officials through whose hands they passed on the way to the founder sometimes kept some of them back, and used them for other purposes -- the earliest “sets” of kaigu* were composed entirely of just such repurposed utensils.

While the gōsu was originally used on the daisu as a koboshi with its lid (and Furuta Sōshitsu states in his writings that he used it in that way, even when he used the gōsu as a koboshi during temae when the daisu was not present)†, it is uncertain whether Rikyū followed this kind of precedent -- or simply used it without a lid, like an ordinary metal koboshi. __________ *The shaku-tate was originally one of a pair of flower vases; the mizusashi was originally a vessel in which “white sake” that was used for Ancestral offerings was kept; the futaoki was a rest for the dipper that was used to scoop “white sake” out for a libation; and the koboshi was either the vessel into which the libation was poured (the shape of koboshi that the Japanese refer to as efugo [餌奮], which means a bag in which the small, plucked birds used to lure hawks back to the fist were kept), or one of the ritual covered bowls (gōsu [盒子]), as here.

†The original rule was that, when displayed on the daisu, the gōsu must never be empty. Thus, before taking it out into the room, a hishaku of cold water was poured inside.

And, during the service of tea, unlike other koboshi, the gōsu remained on the daisu (all other kinds of koboshi were lowered to the mat at the beginning of the temae, and placed next to the host’s leg) -- the cold water it contained preventing the gōsu from becoming hot enough to damage the lacquer.

At the end of the temae, the gōsu was removed, cleaned, refilled with one hishaku of cold water, and then returned to the daisu.

The way some modern schools teach to remove the lid of the bronze mizusashi -- taking it off, wiping away any drops of water while holding it over the koboshi, and then leaning the lid against the front of the mizusashi with the knob facing forward -- is actually the way that the lid of the gōsu was handled. (In the gokushin temae, the lid of the mizusashi is actually placed flat on the ji-ita of the daisu, either in front of the mizusashi, or on a diagonal from it -- if the lid is too large to fit in front.)

When Furuta Sōshitsu used his gōsu, even when he was not using the daisu, he always did so with the lid in place, and with a hishaku of cold water inside, and carrying it out with two hands. When the daisu was not being used, Oribe placed the gōsu next to his leg, and leaned the lid against the side of the gōsu facing toward the temae-za.

³¹Imai Sōkyū, in what is purportedly his account of this chakai (the entry is found in his tea diary*), states that the group moved into the shoin for usucha, writing: “after tea was finished, [we] went out [into] the shoin, where [we] partook of o-usucha; [then] the two people intoned their poems” (o-cha no ato, shoin [h]e deru, o-usucha meshi-agarare, ryō-nin [h]e eika hi ōse-sōrō [御茶ノ後、書院ヘ出、御薄茶召上ラレ、兩人ヘ詠哥被仰候]). No mention of this important point is not found in Rikyū's kaiki; though Sōkyū’s account fails to mention that this change of venue was so that Hideyoshi (and the others -- surely including himself) could take turns performing an usucha-temae†.

While this detail certainly accords with what seems to have been Rikyū's “usual” way of staging things whenever Hideyoshi was present at a chakai (assuming that the venue had a shoin available), a number of other points mentioned in this document conflict with Rikyū's own version‡ -- meaning that either the account given in Book Two of the Nampō Roku, or the version presumably** recorded by Sōkyū in his diary, is (at the very least) suspect. Furthermore, if the group really did move on to the shoin after koicha was finished in the six-mat room, neither Rikyū’s kaiki, nor Sōkyū’s record, for that matter, describes any of the utensils that were arranged in the shoin -- and, necessairly, the set of things would have had to be both extensive and expensive: in addition to a daisu and kaigu, and chawan and tea container(s††), such a setting would require a kakemono, something arranged on the chigai-dana, a book of poetry or other objects displayed on the dashi-fu-zukue (the built-in writing desk that adjoined the jō-dan where Hideyoshi would have taken his seat when not performing) and so forth. __________ *The (fragmentary) document known as the Imai Sōkyū Chanoyu Nikki Nuki-gaki [今井宗久茶湯日記抜書].

†When Rikyū served usucha (as he may have done on the present occasion -- since even if he planned for Hideyoshi and the others to enjoy performing an usucha-temae in the shoin, this would not preclude him from doing so), he usually did so during the koicha-temae, using the tea remaining in the chaire for this purpose -- so it would not go to waste (once used for koicha, the tea could not be used for this purpose again on a later occasion; and for use as usucha, the tea would never be fresher than during the koicha-temae for which it had been ground). Serving thin tea during a separate usucha-temae does not seem to have been his way of organizing the gathering -- except, as here, when it was planned for one of the guests to be doing the temae. (For the host to officiate at a separate usucha-temae follows the format of the chakai used during Jōō‘s middle period. It, however, seems that he repudiated this kind of practice during his last year, possibly under the influence of Rikyū -- who had just returned from a prolonged stay in Korea, and presumably was imitating continental practices in these simplifications.)

‡The Enkaku-ji version of this kakik found in the Nampō Roku has Rikyū arrange the furo on an ō-ita; while, during the goza, the tea container was a small natsume, and the chawan was the Korean Mishima tsutsu-chawan known as Hikigi-no-saya [引木の鞘].

Sōkyū's account, however, has Rikyū using a naga-ita, on which (in addition to the furo) are arranged a [kiji-]tsurube mizusashi, a shaku-tate (not otherwise described), and a bamboo futaoki; while the chaire used during the goza was the “Mossō” [物相] (presumably the chaire that Rikyū called Konoha-zaru [木の葉猿]), and the chawan was a dai-temmoku (the kind of temmoku is not described further, but Sōkyū mentions that the dai is an Amagasaki-dai [尼カサキ臺 = 尼ヶ崎臺]).

Also, in this version, the second of the two poems offered to Hideyoshi by the guests is ascribed to Sōkyū, rather than to Kuroda Yoshitaka (as in Rikyū’s account).

**Unfortunately, neither of these documents exists in the original.

The Enkaku-ji manuscript of the Nampō Roku is (at best) a second-generation copy (and there are a number of differences even between Jitsuzan's original copy, which he made with the Shū-un-an documents in front of him, and the text as he wrote it in the notebooks that he presented to the Enkaku-ji).

As for the Imai Sōkyū Chanoyu Nikki Nuki-gaki, as the title says, the text consists of “selected excerpts” from Sōkyū's tea diary, originally copied, and presumably edited (albeit for private use) in Bunsei 3 [文政三年] (1820), by Takenami-an Kyūsō [竹波庵休叟] (the chajin Inagaki Kyūsō [稲垣休叟; 1770 ~ 1819). The text was then recopied in Bunsei 5 (1822) by a person who styled himself Furyusai Yoshikyō [不流齋良恭; dates or other details unknown]. And his text was subsequently prepared (for publication as a facsimile edition, meaning a careful hand-copy, reproducing his text exactly, was taken, from which the wood blocks were then cut) by Watanabe Shinryū [渡邊信立; otherwise unidentified] in Kōka 4 [弘化四年] (1847).

††Possibly a different tea container was prepared for each of the guests to use during his temae.

Both Hideyoshi and Kuroda Yoshitaka had studied chanoyu with Rikyū, while Sōkyū had studied with Jōō. Hideyoshi might have enjoyed noticing the differences between Yoshitaka’s and Sōkyū’s temae; and preparing a new tea container for each of them to use would have “leveled the playing field,” so to speak.

³²Usucha ha ue-sama hajime, o-shōban tomo ni men-men ni o-tatsuru-sōrote sankō [薄茶ハ上樣ハシメ、御相伴トモニメン〰ニ御立候て參候].

Nothing is said about the utensils that were used for the service of usucha -- though, if it was indeed served during a separate temae, the tea container (at least) would have had to be changed (since a ko-natsume could never hold enough matcha for three portions of koicha, plus potentially six or eight bowls of usucha afterward; and, mechanically speaking, reusing the ko-natsume for usucha would be more troublesome for the guests, since they would have to continue pulling the tea out, rather than scooping, as was more usual).

³³Yūsai, nigori-naki kono mi-yo tote ya ashi-biki no yuwa-i no mizu mo yasuku-sumuran [幽齋、濁なき此御代とてや足引の巖井の水もやすくすむらん].

Hosokawa Yūsai, as the man of letters, chanted his poem first: “in this enlightened age, even the water in a well dug on the edge of a cliff is not easily exhausted.”

Nigori [濁] means muddied, turbid, dirty, and, by extension, (socially/politically) corrupt. Nigori-naki [濁なき] means lacking in these negative qualities.

Miyo [御代] means a period or age; reign. Yūsai is referring to the land under Hideyoshi's rule. Tote ya [とてや] means something like "even this!" or "even now!"

Ashibiki no [足引の], as a phrase, implies something like or related to a mountain (such as “resting on a mountain” or “leaning against a mountain”); though the precise meaning has been lost (the expression is first found in the ancient Manyō-shu [万葉集], but by the middle ages the exact meaning was no longer known). It apparently describes the state or nature of the (subsequently mentioned) iwai [巖井].

Iwai [巖井], while a place name in Kyūshū, literally means a well that was dug on a cliff-face. Such a well is naturally both shallow, and holds a very limited supply of water.

Yasuku-sumuran [安く済むらん]: yasuku [安く] means easy (to do something); sumuran [済むらん] means not used up, not consumed.

The verse praises the enlightened prosperity of Hideyoshi's rule.

³⁴Yoshitaka, yorozu-yo no koe mo kyō yori mashi mizu no kiyoki nagare ha taeshitozo mou [孝高、万代の聲もけふよりまし水の清きなかれハ絕しとそ思ふ].

After which Kuroda Yoshitaka offered his verse: “the voices of the myriad generations [raised in praise] further amplify (those of) the present day: saying that the flowing of pure water will never cease, I believe.”

Yorozu-yo no koe [万代の聲] means the voices of the ten-thousand generations, the voices of all generations. Here koe [聲] seems to mean voices raised in cheers of praise or joy.

Kyō yori [今日より] means beyond (that of) the present day. Mashi [増し] means to increase.

Thus, “the voices of the myriad generations [were raised] to join those of today....”

Mizu no kyoi nagare ha [水の清い流れは] means “with respect to the pure (kiyoi [清い]) flow (nagare [流れ]) of the water (mizu [水])”: flowing water is an allusion to passage of the generations (of Hideyoshi’s family), flowing into the future.

Taesu [絶えす] means to cut, cut off, cease (in this context, it would refers to ones progeny dying out); while taeshitozo [絶えしとぞ] means ceaselessly, without an end (Hideyoshi’s line continues forever).

Mofu [思ふ], or mou [思う], is a classical contraction of the word omofu / omou [思 ふ, 思 う], primarily found in poetry (apparently when there are not enough syllables to go around), and refers to the thoughts of the poet (Kuroda Yoshitaka).

In other words, he is saying that the voices of past generations would be added to those of the present: proclaiming that (like the well in Yūsai’s poem that is never exhausted), the water (in other words, the future generations of Hideyoshi’s family) will continue forever.

³⁵Konnichi ryō-nin [h]e eika-sōrō ōsetsuke, soku-seki ni yomi hi mōshi-sōrō [今日兩人ヘ詠哥候仰付、卽席ニよミ被申候].

This means that on this occasion (literally “today”), immediatly after the two poets (among the three attendants) had finished composing their verses, they immediately recited them. In other words, they probably did not even take time to write their verses down: it appears that they spontaneously gave them voice after considering for just a few moments.

The waka, as a poetic form, is intended to be chanted aloud, not simply spoken, nor read (with the eyes). And Rikyū seems intent on emphasizing the fact that the poems were completely spontaneous. This differed from the sort of format employed on more formal occasions, where the poets excused themselves to consider their verses, and then came back at an appointed time to present their polished efforts. Here it was the raw spontaneity that was offered for Hideyoshi's appreciation.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Audrey Hepburn completa una maratón en bailarinas (parte 1)

He salido esta mañana de casa sin rumbo fijo y con la única intención de distraerme. Hoy es el día uno de un duelo que lleva semanas empezando. Una y otra vez. Acabo de doblar una de las alargadas esquinas de los edificios de l’Eixample. Me gustaría topar con una especie de iglesia donde se divulgue una religión o dogma absurdo y en la que expidan boletines de admisión incluso para imbéciles como yo. Ahora mismo creer en algo me parece imprescindible. Me encuentro en un nivel de dolor alto: de púgil a punto de morder el polvo; solo dos niveles por debajo del knock-out y a uno de la derrota por puntos. Preferiría que me arrancaran una muela sin anestesia. Definitivamente hoy es un buen día.

A los veinticinco minutos no encuentro ni calma ni templo y empieza llover. De mi hombro derecho cuelga una tote bag de tela arrugada blanca que me regalaron en un centro cívico en el que decidí inscribirme durante dos meses a clases de patronaje -detalle en el que no pienso profundizar en este momento-. Dentro de la bolsa acarreo un libro de bolsillo de D.F. Wallace de más de mil páginas con letra minúscula, la cartera, caramelos Halls menta-hierbabuena, una botella de agua que rellené convenientemente en el grifo antes de salir de casa y un paquete de Camel maltratado por el uso. Llegado a este punto, valoro la opción de seguir adelante bajo ese cielo fúnebre tan típico de las películas de Ken Loach y acabar empapado hasta las trancas. Pero algo me dice que lo mío es más como un culebrón venezolano y me siento en una terraza a leer un poco esperando que amaine. Pido cola zero a una señora morena que está intentado encajar las mesas y las sillas en el perímetro de palio verde que bordea el bar. Son las doce y media de la mañana y estoy solo. Levanto la vista de vez en cuando y me sorprende, una vez más, la rapidez con la que la población barcelonesa dispone de paraguas. Pienso en que deben padecer una especie de agorafobia de grado medio-bajo que les permite moverse en un contorno limitado al de su domicilio. Al rato, para de llover. Acabo la bebida, pago y me despido. Justo después la camarera se agacha a por un papel y casi termina en decúbito prono.

Enfilo Consell de Cent hasta Passeig de Gràcia y una vez allí decido ir a ver el mar. Por el camino tropiezo con un turista fotografiando la puerta de un Zara (¿?). Le pido perdón hasta en tres idiomas y me alejo pensando que el que debería haberse disculpado era él. Luego me llama Albert para describirme el último trabajo que le ha ofrecido el Sindicato del Crimen de la Hostelería (S.C.H.) y para ponerme al día de sus devaneos por el inframundo de Tinder. Llego a la Catedral y tengo la tentación de desviar mi objetivo por unos instantes y entrar en la plaza de Sant Felip Neri, pero lo descarto al ver a un guía free tours gritón al que sigue una fila de alemanes.

El barrio gótico me recibe con las consabidas meadas callejeras y un fuerte olor a kebab-con-todo-pero-sin-picante-y-poco-queso. Pese a que llevo entre pecho y espalda solo dos galletas de chocolate, descarto el consumo. Las mantas que recorren el lateral del paseo marítimo -ya en la Barceloneta- se disponen en hileras perfectamente alineadas. Compruebo que se han puesto de moda las gafas de sol redondas y los cristales de colores extravagantes. Los tintes de las zapatillas de imitación incitan, de igual manera, al consumo de estupefacientes.

Pienso en todo momento en cómo he llegado a este punto con P. La odio a ratos, me culpo en otros y nos comprendo a ambos. Parece un avance pero no lo es. La echo mucho de menos. Ya no va a volver a hablarme.

Tengo la cabeza más embotada que el cielo que se aproxima a mi izquierda. A mi derecha los bañistas se refrescan ajenos a todo. Escribo con mi teléfono a Andreu para informarle de dónde estoy y para asegurarle que hoy voy a comer bien (lleva días preocupándose por este asunto). No pienso morir de hambre, “yo lo llevo así”, le digo, como siempre. Me anima a seguir y luego me envía una foto del monstruo de las galletas. Dice que sin gafas pierdo mucho.

Bordeando la sucesión de playas que conforman el litoral de Barcelona compruebo que la sintonía de los chiringuitos se mantiene inmutable al paso del tiempo. El abanico musical abarca desde ritmos latinos trasnochados como la “Mayonesa” -ellamebatecomohaciendomayonesa- hasta el chill-out ibicenco que escuchan unos horteras recostados en puffs negros con marcas blancas de salitre.

La humedad es relevante y las marcas de sudor de mi camiseta conforman algo parecido al mapa de Noruega.

Xuan Álvarez

(cont.)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Carlos Álvarez (Rigoletto) Gran Teatre del Liceu Fotografia ®A Bofill

René Pape Méphistophélès al MET 2011 Foto Ken Howard Metropolitan Opera

De tots els qüestionaris que he publicat fins ara en cap he estat tan salvatgement mutilador com en el de Leonor que publico avui,

Pràcticament en totes les contestes s’ha desbordat en apassionades respostes que espero que amablement tingui la delicadesa de fer-vos-en coneixedors, ja que òbviament ens perfilen la seva generosa personalitat, alhora que el seu vast coneixement, sempre discret però per poc que estigueu atents als comentaris que deixar sovint a IFL, denoten a banda d’una educació exquisida un profund amor a la música i al cant.

Us deixo ell seu qüestionari tot esperant que ella l’acabi de completar tal i com me’l va enviar originàriament amb tots els afegitons que he escapçat triant en tots menys un dels casos, el primer nom que apareixia a la seva llista. Ella sap perquè en un cas m’he permès de desplaçar a una habitual al segon lloc i deixar el lloc d’honor de les sopranos a la Lorengar. Estic segur que estarà encantada i s’ho mereix, és clar

¿La primera vez que fuiste a la ópera qué año fue? Fue el 10 de junio de 1987 (aunque antes presencié “La serva padrona” en el patio de la Universidad de Barcelona); maravillosas experiencias.

¿A qué teatro? El Gran Teatro del Liceo.

¿Qué ópera viste? “Werther”.

¿Tus padres iban o van a la ópera? No iban aunque acabaron asistiendo con placer; mi madre se enamoró de este género y mi padre adoraba la zarzuela, que escuchaba siempre.

¿Qué compositor operístico prefieres? Wolgang Amadeus Mozart. Ningún secreto.

¿Cuál es el aspecto que valoras más de una representación operística? Quiero el completo ensamblaje de todos los elementos (palabra, canto, escena) pero, en especial, las voces adecuadas, el canto.

¿Cuál es tu tenor predilecto? Sin detrimento a otros: Alfredo Kraus …

¿Cuál es tu soprano predilecta? Mi tríada: Pilar Lorengar…

¿Cuál es él tu barítono predilecto? Carlos Álvarez.

¿Cuál es tu mezzosoprano predilecta? Grace Bumbry…

¿Cuál es tu bajo predilecto? Me sigue fascinando René Pape.

¿Cuál es el teatro de los que has visitado que más te ha impresionado? El Teatro Alla Scala de Milán. Confieso que me faltan muchos aún.

¿Podrías vivir en una ciudad sin teatro de ópera? Me costaría demasiado; viajo para asistir y disfrutar más de ella.

¿Cuál es tu ópera preferida? Seguro, de Mozart: a veces es Le Nozze di Figaro…

¿Qué ópera detestas? No detesto ninguna; me puede gustar más o menos, pero no rechazo ningún estilo ni compositor.

Valora de 1 a 10 la importancia del director de escena en una representación operística Un 3.

¿En qué ciudad del mundo que no sea la tuya y con teatro de ópera, te gustaría vivir? Confieso que en muchas, me gusta variar bastante de ambiente: Barcelona…Soy viajera, por naturaleza.

¿Cuál es el libretista operístico preferido? Da Ponte por sus temas…

¿Cuál es tu héroe de ficción operística? El Fígaro mozartiano.

¿Cuál es tu heroína de ficción operística? Carmen.

¿Cual es la grabación operística que te llevarías a una isla desierta? ¿Solamente una? Si se encontrara, el “Don Carlo ” escalígero con Callas; hasta entonces, “Die Zauberflöte” de Mozart, dirigida por Solti y con Lorengar, Deutekom, Prey, Fischer-Dieskau junto a la Filarmónica de Viena.

¿Cual es el director de orquesta operístico preferido? Georg Solti…

¿Cual es el director de escena preferido? Me gustan la estética de Guth…

¿Cual es la representación operística que te hubiera gustado asistir? La representación de “Medea” por Maria Callas en Milán.

¿Cual es la ópera barroca que más te gusta? Como estilo, del Barroco adoro la zarzuela barroca (la recomiendo encarecidamente: Durón, Literes, Nebra); como ópera barroca, La “Didone” de Cavalli…

¿Cual es la ópera clásica que más te gusta? “Idomeneo, re di Creta” de Mozart.

¿Cual es la ópera romántica que más te gusta? Últimamente, me apasiona la ópera rusa y en otros momentos, otras; eso sí, nunca me canso de escuchar “El cazador furtivo” de Weber.

¿Cual es la ópera del siglo XX que más te gusta? ¿Una solamente? En fin, “Turandot”, de Puccini.

¿Cual es la ópera del siglo XXI que más te gusta? Hay varias, me quedo con “Doctor Atomic” de Adams…

Si pudieras elegir una vocalidad lírica, ¿Qué te gustaría ser: soprano, mezzosoprano, contralto, tenor, barítono o bajo? Soprano drammatica d’agilità.

Us convido al costat de Leonor a assistir a aquella mítica Medea de Cherubini dirigida per Leonard Bernstein al Teatro alla Scala el 10 de desembre de 1953 amb Maria Callas, Gino Penno i Fedora Barbieri, i a on com a la majoria de tots nosaltres a la Leonor li hagués agradat assistir

Gràcies Leonor i perdona les meves estisorades.

La setmana vinent ens visitarà el qüestionari d’Ordet

EL QÜESTIONARI IFL DE LEONOR De tots els qüestionaris que he publicat fins ara en cap he estat tan salvatgement mutilador com en el de…

#Alfredo Kraus#Carlos Álvarez#El Qüestionari IFL#Georg Solti#Grace Bumbry#Medea#Pilar Lorengar#René Pape#Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

0 notes

Text

Kolejny, wyjątkowo pomyślny rok dla polskich stoczni

Kolejny, wyjątkowo pomyślny rok dla polskich stoczni

W ubiegłym, 2016 roku Gdańska Stocznia “Remontowa” SA przebudowała statek armatora Stena na metanol i realizowała przebudowy dwóch wież. Zainstalowała pliczki spalin tzw. scrubbery na 25 statkach i zadokowała na remonty przeszło 200 statków! Był to najlepszy w ciągu ostatnich dwudziestu lat rok w “Remontowa” SA!

Remontowa wykonuje także pełen zakres remontów dla statków wojskowych mogąc się…

View On WordPress

0 notes