#thoracosaur

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Very late on this one but I think theres some cool stuff to talk about.

I actually covered this formation extensively a few years ago when giving the Wikipedia page a major overhaul at the request of someone on discord, so the research phase for Josch was mercifully easy (at least for me, not so much for those making the reference size chart).

Really one of the main things that the research focused on was which localities to choose. For reference, Jebel Qatrani spans the Eocene-Oligocene boundry and has localities representing different time intervalls. For example, locality L-41, which is the single most specious, was deposited during the Late Eocene, localities A and B right after the boundry and localities I and M are among the most recent. After some debating I and M kinda cristalized into the main ones to use, they are pretty close together so the fauna was likely to overlapp a good deal, they had some iconic animals and they also preserve a bulk of the bird fauna, which really helped fill lots of the space to not overcrowd with mammals.

Obviously my personal highlight was the featured crocodilian, Eogavialis africanum. Right out of the gate its an interesting one. Traditionally, Eogavialis, like other closely related forms (informally "thoracosaurs") have been recovered as some type of gharial, generally closer to Indian Gharials than Tomistoma (in old phylogenies featuring Tomi as a crocodylid, thoracosaurs are still deemed gharials proper).

Now I initially had like three whole paragraphs typed on why I don't think this is the case, but for brevity's sake I'm going to save that for a future post on thoracosaurs in general (perhaps its something to cover after I'm done with mekosuchines). So for now, just know that tho it could be an early African gharial, its also possible that Eogavialis is a member of a much more ancient, non-crocodilian group of Eusuchians that just happens to look similar to gharials and that went extinct during the Miocene.

Also fun fact, the patterns and colours are based on modern day broad-snouted caimans.

Also while not featured in this piece I wanna give a shout out to "Crocodylus" megarhinus, a more robust crocodilian from the formation. As you can guess from the "", its no longer thought to belong to Crocodylus but is its own, still unnamed genus, interestingly closely related to the enigmatic mekosuchines endemic to Oceania. The size chart below also features Crocodylus articeps, the slender jaws at the very bottom. Though this species was long deemed a juvenile "C." megarhinus, comparisson with actual juveniles of the latter shows this to be obviously false. Alas the holotype has been lost and it is now deemed a nomen dubium.

I also wanna give a brief shout out to the bird fauna, which is quite interesting in its own right and features a lot of taxa that match the swampy environment depicted here. For instance there's Palaeoephippiorhynchus, a large stork related to saddle-bills, marabous and jabirus and in a similar size range. There's also Goliathia, a "giant" shoebill. Though, as it turns out, the holotype is smaller than a modern shoebill and one of the referred specimens is only slightly more robust in some ways and not in others. So while interesting, its name (envisioned for what was assumed to be a heron) is not that fitting anymore. Speaking of heron, there is also Xenerodiops, with its uniquely shaped bill. Some researchers have argued that this genus was a type of night heron based on a humerus, though here it is depicted as more generalized given that the humerus and holotype bill have no direct evidence for having belonged to the same animal.

My personal favourites among the birds are the local flamingos and lilly trotters. Flamingo are represented through remains similar to those of Palaelodus (which I talked about in greater detail here and here) and thus likely belonged to that genus or another palaelodid. In short, these birds likely already had a diet not dissimilar to modern flamingos, but lacked the extreme bill curvature. Lilly trotters are better known from the formation and represented some of the earliest records of this family. Three species in two genera have been named, with this one in particular being Janipes, here depicted similar to a pheasant-tailed jacana, which is closely related to at least one of the two Jebel Qatrani jacanas (Nupharanassa specifically). It's been noted that all jacanas from this formation are larger than their modern kin.

Obviously theres a lot more cool stuff about the formation, including the incredible diversity of hyraxes, the presence of the weird ptolemaiids, three different elephants, the bizarre Arsinoitherium, early sirenians (really this place was a hot spot for afrotheres) and a vast number of primates. But all this goes beyond what I'm most familiar with.

Results from the Jebel Qatrani formation #paleostream!

Arsinoitherium might be the most iconic animal from here but that doesn't make the rest of the fauna less interesting!

#jebel qatrani formation#gebel qatrani formation#fayum#egypt#paleontology#palaeoblr#long post#xenerodiops#palaelodus#janipes#jacana#flamingo#crocodylus megarhinus#eogavialis#eogavialis africanum#thoracosaur#croc#crocodile#gharial#eusuchia#oligocene#prehistory#goliathia#shoebill#paleostream

405 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gharial rescued from sea

Another instance of more recent croc news, a "giant" gharial was found in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Balsore, eastern India.

According to news articles, the animal, an adult Indian Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus), meassured around 13 feet or in metric close to 4 meters in length while weighing some 118 kilos.

The gharial apparently got caught in a fishing net and was found by fishermen, who promptly reported their catch to the Forest Department. The department then handed the animal over to Nandankanan Zoological Park, where the crocodilian still resides.

That's all the information given to us by the article, which you can read here, but there's two key notes I wanna touch upon.

The first is size. At 4 meters, this gharial was decently large for sure and as someone who has seen a (stuffed) female of slightly greater proportions I can attest that it must have been an impressive animal. However, I think its worth mentioning that Indian gharials are capable of growing even larger. The female I just mentioned is accompanied by a stuffed male nearly 5 and a half meters in length, with some reports claiming sizes even greater than that.

Me and the Vienna gharials

The second point is the mysterious presence of a gharial this far out at sea. This is simultaneously unusual yet also very much reasonable from the point of view of paleontology.

On the one hand, Indian gharials are critically endangered. Their range today is incrediply spotty and isolated and to my knowledge they aren't found anywhere near the coast these days.

However when you look at how the range was meant to be like, then you see that they definitely reached the river deltas and coastal regions. So our image of gharials as this inland freshwater species is more based in circumstance than reality.

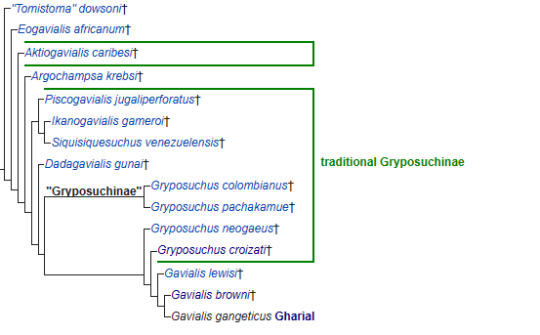

This becomes especially apparent once you begin to consider the paleobiogeography of gharials. Based on our current knowledge, gharials most likely originated somewhere in Eurasia or Africa, spreading from there across much of the eastern hemisphere and beyond (full disclosure I am not considering thoracosaurs to be gavialoids, more on that can of worms later maybe). Anywho, phylogenetic analysis and the fossil record both suggest that gharials then crossed oceans and settled South America sometime prior to or during the Miocene, where they diversified and gave rise to the gryposuchines. Some species even remained saltwater species, such as Piscogavialis, which lived in the coastal waters of Peru.

Although gryposuchines were once thought to be a distinct subfamily of gharial, recent research suggests that they were but an evolutionary stepping stone, with some South American form once again crossing the Pacific and settling down in Asia where the much more basal "tomistomines" or false gharials (a misnomer) still resided. And while the gryposuchines of South America went extinct, those that returned to Asia survived and eventually gave rise to the Indian Gharial of today.

Left: A cladogram showing the relationship between Gryposuchinae and modern gharials Right: Piscogavialis swimming overhead some marine sloths of the genus Thalassocnus by @knuppitalism-with-ue

So ultimately, seeing a gharial in saltwater is much less bizarre than one would initially think, its just that habitat destruction and overhunting have largely pushed these gorgeous reptiles further inland and to the brink of extinction.

#gharial#indian gharial#gavialis gangeticus#gavialidae#news#croc#crocodilia#crocodile#india#herpetology#gavialinae#gryposuchinae#piscogavialis#some paleontology#palaeoblr

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

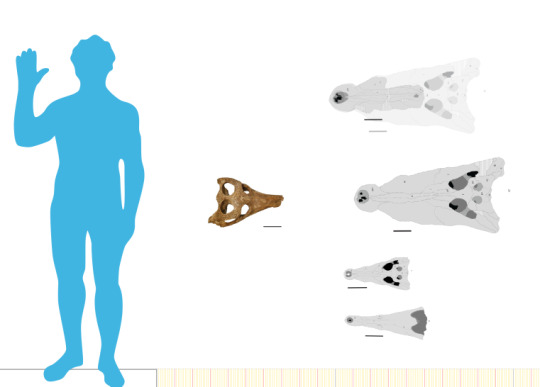

I was requested to make a size comparisson for Eothoracosaurus, a late Cretaceous thoracosaur from the United States. So here it is. The proportions are based on the Thoracosaurus reconstruction by Evan Boucher, which resulted in an animal approximately 4.6 meters long.

Eothoracosaurus is a thoracosaur, which historically have been regarded as false gharials or gharials. Even more recently, the idea has appeared that they weren't even true crocodilians, but a type of basal Eusuchian (a hypothesis I personally support).

Remains of this animal were found in marine sediments that also housed mosasaurs, sea turtles and sharks.

#eothoracosaurus#thoracosaur#crocodile#palaeoblr#croc#cretaceous#prehistory#reptile#steve irwin for scale#size chart

112 notes

·

View notes