#this was during the tim duncan/tony parker/ginobili era

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Wait, no, now I made myself sad thinking of Eddie skipping some basketball games once Chris left. Buck shows up one day in his basketball gear and ball in his hands and makes Eddie come play basketball. It's just a one on one game because he knows Eddie doesn't want to be around a lot of people. They're sitting taking a break, and Eddie's all thanks you didn't have to do this. I know you don't like basketball. Buck responds with a but you do, and I like you, so it's not exactly torture being here, and it made you smile again.

you sent this to me i think after i rb something about Buck sidelining basketball and this is very sweet 🥺🥺

Eddie Diaz canonical quality time love language guy.......canonical basketball enjoyer......i just KNOW he's a spurs fan too, a man of taste. he definitely owned a Ginóbili jersey

#i loved ginóboli so much that was my GUY#the spurs were my first fave basketball team because i lived in LA and hated the Lakers after shaq left#this was during the tim duncan/tony parker/ginobili era#also i know im weird about basketball but it's so odd to me that one of buck's character traits is NOT LIKING BASKETBALL#like what do you mean you dont like basketball????#it's such a good sport???? whats not to like??????#see this is why chimney and i would be best friends. because i agree. it is the sport of kings.#sibyl answers#anon

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

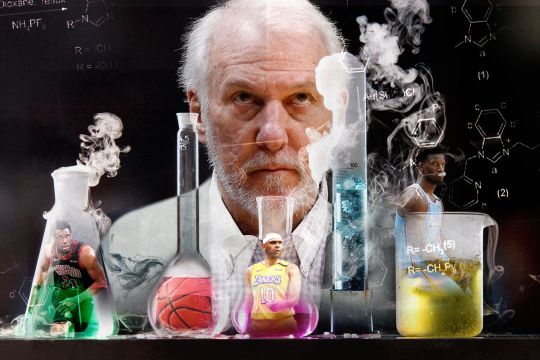

The NBA has a chemistry problem

How NBA teams struggle to create chemistry in an era when rosters are turning over faster than ever.

The NBA is a league of change. Recent roster turnover has been spurred by a number of factors, from an inflated salary cap and shorter, more exorbitant contracts, to restless owners, to star players progressively embracing their own power. Teams have been forced, at breakneck speed, to become comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Before the NBA went on hiatus due to the coronavirus pandemic, chaos was its new normal: compelling, delightful and anxiety-inducing. But the constant shuffle also sparked an existential question among hundreds of affected players, coaches and front office executives: How can chemistry be fostered in an increasingly erratic era of impatience, load management, reduced practice time and youthful inexperience?

“Every year you have six new teammates,” Houston Rockets guard Austin Rivers said in an interview with SB Nation. “It’s like gaw-lly! In some ways you wish that would stop.

“It’s a new NBA, man. Guys are playing on a new team every year now, and it has nothing to do with how good of a player you are, it’s just how the NBA is. I have teammates who’ve played on eight, nine teams. I mean, that’s fucking nuts. I don’t ever want to go through something like that.” (Rivers is 27 years old, and on his fourth team in seven NBA seasons.)

Over the past six months, dozens of players, coaches and executives across the NBA spoke with SB Nation about the state of the league’s chemistry, and why creating cohesiveness now is more difficult and demanding than ever before. Their responses sketched a blurry future for the league.

“It’s amazing how fast players change in today’s NBA,” Indiana Pacers general manager Chad Buchanan said. “From when I got over here two years ago, Myles [Turner] is the only player who’s still here.

I have teammates who’ve played on eight, nine teams. I mean, that’s fucking nuts.” - Austin Rivers

Last summer, nearly half of the league’s talent pool swapped jerseys. Seemingly every roster in the league was forced to learn complicated new personality quirks and on-court tendencies. Honed locker room dynamics and hierarchies changed dramatically.

Chicago Bulls forward Thaddeus Young has played for four teams in the last six years after spending his first seven with the Philadelphia 76ers. Few people know better just how precious chemistry can be.

“With how the salary cap is going, teams are not locking themselves into long-term deals anymore, where they have four to six guys on four-year deals,” Young said. “It’s definitely tough because you don’t know each other. The communication is gonna be off. The teams that you came from before, you might be driving the basketball and you might be used to a guy being in the corner and that guy might not be in the corner.”

The NBA may be long past being able to reverse the course of roster turnover, but teams are doing their best to mitigate any downsides. The teams that have done the best job tend to think of chemistry in two buckets: personal and performance. The former contains how players interact away from the game, and the latter contains what happens on the court. However, personal chemistry often informs performance, and vice versa. Once players are comfortable off the court, their on-court relationship improves.

Take Los Angeles Lakers forward Jared Dudley, for example.

“When I got here I’d turn the ball over throwing to our centers because they expected a lob,” Dudley said. “I don’t really throw lobs, I’m more of a bounce passer.”

Dudley solved his problem by initiating conversations with LA’s big men, verbalizing his own in-game habits so that everyone could get on the same page. Not all NBA players feel so comfortable expressing themselves, however. Especially when an on-court situation is more complex than what to do on basic pick-and-rolls.

“When the personal chemistry exists, the performance chemistry is often very easy because the performance chemistry is sometimes a function of hard conversations,” one Western Conference GM said. “The personal chemistry allows a guy to say, ‘Hey man, in the second quarter last night there were like four straight defensive possessions where four of us were back in transition and you weren’t. You really put a ton of pressure on us to cover a five-on-four when you were lobbying the officials for a call. It took you forever to get off the deck. Come on, man.’”

Over the past 20 years, no organization has been more conscious of team chemistry than San Antonio. The Spurs are also far and away the modern era’s most influential organization: Nearly one third of the league’s rival head coaches and front office executives can be traced back to head coach Gregg Popovich.

Drafting multiple Hall of Famers undoubtedly factored into the Spurs’ success, but their efforts to maintain an open atmosphere for stars and role players alike — one that obsessed over values of tolerance, respect and empathy — also separated them from everyone else.

However, San Antonio’s year-to-year continuity is also becoming progressively rarer, if not extinct. When Chicago Bulls head coach Jim Boylen was a Spurs assistant during the 2014-15 season, they had brought back 14 members of the previous year’s 15-man roster.

“And of those guys, a bunch of them had been together for years,” Boylen said. “Now there’s approximately 6.5 new guys per team. That’s unheard of.”

To ignore San Antonio’s sprawling influence would be like praising observational comedy and never once mentioning Jerry Seinfeld. But even the Spurs are vulnerable in a league where turnover is the status quo. Prior to the 2018-19 season, they traded Kawhi Leonard and Danny Green, and lost in the first round of the playoffs for the second year in a row. Prior to this season’s hiatus, they were on track for their first losing record in 21 years.

“The Spurs don’t have an advantage anymore,” Dudley said. “We all have a disadvantage. Now it’s who has the most talent. Talent is gonna win out. Talent and vets.”

Continuity is comfort

In 2012, James Tarlow was an economics student at the University of Oregon when he presented a paper titled “Experience and Winning in the National Basketball Association” at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference. Tarlow wanted to know how roster continuity relates to team chemistry, so he pulled data from 804 NBA seasons played by 30 franchises between 1979 and 2008. He defined chemistry as “the number of years the five players playing the most minutes during the regular season have been on their current team with one another.”

“I got an actual measurement of how important [chemistry] is,” Tarlow said in a conversation with SB Nation in March. “And it’s pretty dang important. If you keep your team together it’s like a third of a win for a year, which, people don’t appreciate that and it doesn’t seem like much, but if you have a team that stuck together for several years, that turns into another game or two. That’s going to get you into another round in the playoffs.”

Bill Russell once wrote, “There is no time in basketball to think: ‘This has happened; this is what I must do next.’ In the amount of time it takes to think through that semicolon, it is already too late.”

It’s an intuitive idea: The longer we’re around people, the better we know how they’re going to behave under certain circumstances. Just think of the short-hand forms of communication you’ve established with your closest friends, family members and coworkers. Those subtle gestures and glances are especially helpful in sports, where a split-second miscommunication can be the difference between winning and losing.

“You go back to those San Antonio days, the winks and blinks and the nuances [where Tim] Duncan would find Tony [Parker] on a backdoor, or Manu [Ginobili] would find Timmy on a lob, that evolved over time, and lots of times [time] isn’t afforded,” said Philadelphia 76ers head coach Brett Brown, who spent nine years as a Spurs assistant. “You need time to have that sophisticated camaraderie, gut feel, instances on a court that require split the moment decisions.”

Continuity by itself doesn’t lead to winning, of course. In some cases, it might only extend mediocrity. And if winning a championship is an organization’s organization goal, then it should first pursue star power. But continuity is a boon to coaches, who can implement more complex strategies if they’re able to retain a core group of players year after year.

“Right now with the influx of new players, you’re having to really keep your playbook and your schemes at a basic level because you are teaching more,” Charlotte Hornets head coach James Borrego said. “You’re just starting almost at a ground level every single year in a lot of different ways, where the teams that have had success for years and years, they’re building on every single year.”

You never actually practice anymore … like when I first got in the league, everybody had a million plays.” — Steve Clifford

The lack of in-season practice hours only compounds coaches’ frustrations. With shorter timeframes to fold new players into their system and culture, coaches around the league feel they need to adapt quicker than they ever had before.

As Boston Celtics head coach Brad Stevens joked, “We get three weeks to get ready for a season, then we never practice again.”

Orlando Magic head coach Steve Clifford believes that the league office did the right thing by limiting back-to-backs across every team’s schedule. During his first two years as head coach of the Charlotte Hornets, they played 22 back-to-backs each season, while only 11 were on the docket this season for Orlando. But the schedule shift has hurt in unforeseen ways.

“When you play a back-to-back you usually get two days off, most times, right?” Clifford said. “So you give them a day off and then when you come in you can practice. They’re rested, you bring referees in. You practice. You actually practice.

“You never actually practice anymore … like when I first got in the league, everybody had a million plays, and you had to know the plays and stuff, and now if you do it’s an advantage but people don’t look at it like that.”

A side effect of so much player movement may be a simplification of the product. NBA teams have evolved to emphasize an up-and-down, free-flowing style of play that is largely the byproduct of an analytical revolution to prioritize threes, layups and free throws. Modern basketball is filled with pick-and-roll heavy offensive actions that don’t require the same on-court intimacy as a stockpile of elaborate set plays.

“My gut tells me that roster turnover is what’s causing the thinning of playbooks,” one western conference general manager said. “And the thinning of playbooks is what’s causing this standardization of playing style.”

Players feel it, too. “Most teams don’t do anything. Really it’s just take the ball out the basket, pick-and-roll, and run,” Rivers said. “The coaches are really here to guide you now. It’s crazy. It’s more ATO’s (after time-out plays) and out of bounds, and late clock, fourth quarter, that’s when coaching really comes in play. That’s all we go over in shootaround. Most of our stuff involves defense because our offense is fucking ridiculous, man. We don’t really do anything on offense.”

Even teams that have gone out of their way to maintain continuity—like Clifford’s Magic, which returned 85 and 82 percent of their minutes over the past two seasons, respectively—are not immune to change, and all its myriad effects on strategy.

“The game is what they wanted it to be when they changed the rules, and the level of execution is still high, obviously,” Clifford said. “It’s not nearly the gameplanning league that it was even seven or eight years ago.”

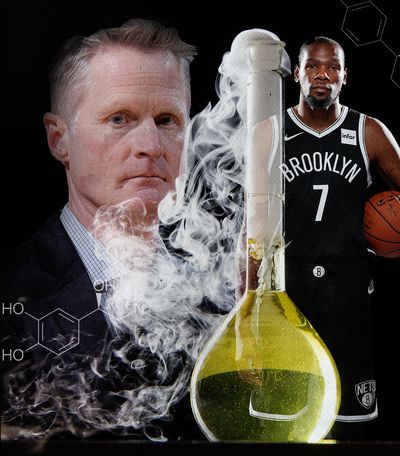

Sustained success is not possible without collaboration, and collaboration becomes habit when several contributors spend thousands of minutes battling together in the same system. The Golden State Warriors had the benefit of several superstars as they won three championships, but they also had an iron collective grasp of what they wanted to accomplish on every possession.

“I think there is a level of beauty that exists with the game that is tougher to reach with the turnover,” Warriors head coach Steve Kerr said. “For example, if Draymond [Green] ever caught the ball in the pocket off of a high screen with Steph [Curry], Andre [Iguodala] knew exactly where to go and Draymond knew exactly where he was going to be. We didn’t even have to practice it. And that’s why you saw, frequently, either the lob to Andre along the baseline or Andre spaced out.”

How teams think they can engineer chemistry

NBA teams have been thinking about how to manufacture chemistry for years, long before this accelerated era. None of these billion-dollar corporations can ever be sure how well their efforts actually work, however. Their adjustments have always been based on in-game progression, but success also depends on other obvious factors, like talent, injuries and dumb luck.

A difference between then and now is that players are driving roster decisions to a greater extent. They have much more leverage within organizations, and the biggest stars can take their talent elsewhere if the locker room doesn’t jell quickly enough. For many teams, that means they have to proactively foster strong bonds among teammates by encouraging new and returning players to stick around the practice facility during the offseason.

“The summer time is big for us,” Borrego said. “We can’t demand it, but we encourage it … Guys can really settle down and connect, really understand their teammates, understand their coaches, and it’s just a much more comfortable situation that allows for chemistry to be built and grown.”

The Hornets also organize team dinners when they’re on the road, a practice Borrego borrowed from his time in San Antonio. When asked if those dinners are mandatory, he gave a wry smile: “They are team dinners. Then there are others that happen organically on their own, and I want our players to do that. If they’re doing it on their own that’s even better than me organizing something.”

If there’s somebody in your organization that hasn’t gotten over himself or herself they’re a pain in the ass ... they can’t be happy for somebody else’s success.” — Gregg Popovich

As one former Spur told ESPN: “To take the time to slow down and truly dine with someone in this day and age — I’m talking a two- or three-hour dinner — you naturally connect on a different level than just on the court or in the locker room. It seems like a pretty obvious way to build team chemistry, but the tricky part is getting everyone to buy in and actually want to go. You combine amazing restaurants with an interesting group of teammates from a bunch of different countries and the result is some of the best memories I have from my career.”

Of course, Popovich was also good at finding players he wanted at the table.

“The more you can stay together, the more the chemistry builds. But still chemistry is more a function of the character of the players than it is anything else,” Popovich said. “I always talk about getting over yourself. And if there’s somebody in your organization that hasn’t gotten over himself or herself they’re a pain in the ass and they make it harder for everybody else because they can only feel about their success. They can’t be happy for somebody else’s success. It has to be about them. If you don’t have that then nothing else is gonna help you have chemistry. You can’t make it happen.”

Still, every coach tries to get everyone on the same page. As players digest their new surroundings, it’s important that everyone — coaches, players and executives — understand their expectations for one another. Rockets head coach Mike D’Antoni boiled his own approach down simply: “Don’t ask somebody to do something they can’t do. If you’re gonna have to change a guy, you might not want to bring him in in the first place.”

It is impossible for any team to keep all 15 players in the locker room happy at the same time; they’re human beings who are all going through their own real life issues. But a haphazard onboarding process will create headaches down the road. According to Buchanan, coaches have to be able to anticipate players’ questions.

“‘Why am I not getting to do this?’ or ‘Why am I not getting to play more?’ or ‘Why am I not playing with that guy?’ or ‘Why am I not starting?,’” Buchanan said. “You try to get that communicated up front so the player knows what he’s stepping into, because lots of times chemistry issues evolve from a lack of communication.”

When general managers and coaches are unaware of loose frustrations, they risk one player venting to another, sewing animosity that does irreparable damage to the entire team. Left unattended, a team can spiral into soap opera.

“It’s not difficult to create chemistry,” Atlanta Hawks head coach Lloyd Pierce said. “It’s more about sustaining it through the course of 82 games with so many ups and downs. Obviously [we had] some of those moments with John [Collins] being out and Kevin [Heurter’s] injury. Roles start to shift and some guys weren’t ready for it, so the frustration of that kicked in.”

The Hawks have done two things to stave off that seemingly unavoidable discomfort. The first is an all-in dedication to how they play, in which everything revolves around pick-and-rolls with Trae Young and a rim-rolling big. By keeping the gameplan simple, they can plug in pieces as needed.

“When Trae masters it and everybody else understands it, you know, you roll a little bit harder and you shake up a little bit better, and you slash a little bit better. That’s who we will become,” Pierce said. “Any big that comes to our roster [knows,] ‘I can play here because I know I’m gonna get the ball at the rim.’”

The Hawks also have a breakfast club that Pierce took from his time as an assistant under Brown in Philadelphia. Every time the club meets, players stand up in front of their teammates and discuss something that matters to them. Earlier this year, Collins enlightened the room with a powerpoint presentation about what it was like growing up in a military family. Heurter talked about growing up in upstate New York and losing high-school friends in a drunk-driving accident.

Former Hawks center Alex Len gave a particularly tender presentation last season that moved his head coach.

“You’re barking at Alex Len. ‘This fucking guy, he doesn’t compete, he doesn’t appreciate this,’” Pierce said. “Well, Alex Len talked about why he couldn’t go to the Ukraine for the last seven years. ‘Wow, I didn’t know you had such a tough time with that. I’m over here fucking yelling at you for not rolling in the pick and roll. I don’t know you’re dealing with this Ukraine thing for the last seven years and not being able to go home and see your grandparents. My bad. I’ve got to get to know you a little bit better.’”

Three years ago, Kings owner Vivek Ranadive asked a communications coach named Steve Shenbaum to work with his team. In 1997, Shenbaum founded a company called Game On Nation, which helps corporate executives, military personnel and government employees in addition to professional sports teams.

Within the past decade, Shenbaum has been brought in by the Lakers, Trailblazers, Nuggets. Cavaliers, Grizzlies and Mavericks, and agent Bill Duffy has asked Shenbaum to assist several of his clients, including Carmelo Anthony, Yao Ming and Greg Oden. He has more than 100 improvisational and conceptual exercises to help clients build self-awareness, selflessness, confidence and other traits that enable character development.

A favorite is called “last letter, first letter,” in which two teammates have a conversation with one rule: as they take turns speaking, they must start with the last letter of the other person’s last word, and keep the conversation going. The exercise forces both parties to listen, let one another finish and focus in ways they otherwise might not.

“My hope is I am planting seeds and empowering the players and the staff to take what they’ve experienced and run with it and multiply it,” Shenbaum said. “I want them to see each other in another light.”

Shenbaum has many telltale signs of good and bad chemistry, but a big one is how well veterans are buying in. In a league that’s getting younger and younger, it’s imperative that older players command respect in the locker room and impose a will to succeed.

Dudley believes veterans who might not even be in a rotation can earn their money by bringing everyone together in ways a coach or GM can’t. During his one year in Brooklyn, he organized dinners, trips to the movies, parties and other events away from the game that involved the whole team.

“Then, when we were in film sessions and I would call them out, they took it as love and not criticism,” Dudley said. “You’re developing a relationship and then you can tell them, Spencer [Dinwiddie] or a guy who thinks he should play more, ‘this is why you’re not playing. This is your role for this team.’ Rondae [Hollis-Jefferson], he got benched: ‘Hey Rondae, for you to stay in the league, this is what you gotta do. On this team you’re not a starter anymore but there’s gonna be times they call on you.’ He stayed ready.”

Almost everyone interviewed for this story agreed that chemistry can’t be forced. Players on contending teams have to go through organic hardships together before they can become comfortable enough for the difficult conversations that facilitate progress. Some teams don’t believe it’s necessary or appropriate to ask their players to spend more time together than they already do. They believe that players should figure out issues among themselves, and that a front office’s biggest role is doing good background research on everybody they bring aboard. Coaches are there to take a team’s disparate pieces and position them to succeed.

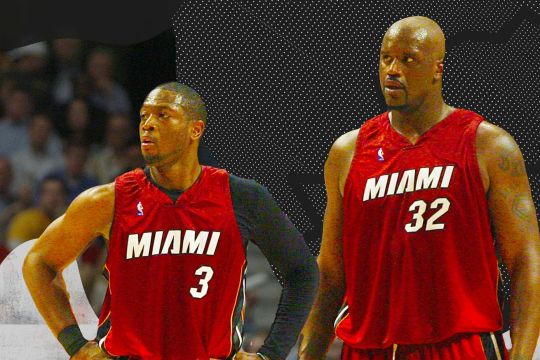

“I think everybody’s budgets on team meals now has skyrocketed league wide because of the San Antonio Spurs,” Miami Heat head coach Erik Spoelstra laughed. “The more important thing is getting a team on the same sheet of music about your style of play and an identity on both ends of the court, understanding what’s important, what the standards are, the expectations, role clarity. These things fasttrack, in my mind, chemistry. It’s always nice if guys like each other and they go out to eat on the road, have dinner together. But that doesn’t guarantee anything.”

Spoelstra knew early on that Jimmy Butler’s oft-misunderstood persona would have no trouble fitting in with several players on Miami’s roster because they all shared the same sense of duty.

It’s always nice if guys like each other and they go out to eat on the road, have dinner together. But that doesn’t guarantee anything.” — Erik Spoelstra

“I’ve noticed with Goran and Jimmy in particular, they have such a beautiful on-court chemistry because they’re in their 30s, they’re only about winning right now. They don’t care about anything else. If you want to define on-court chemistry, in my mind it’s how willing are you to help somebody else. And how willing and able are you to enjoy somebody else’s success when it happens.”

The “character vs. talent” debate isn’t new among NBA decision-makers. But going forward, we may see teams value the former more than they have.

“If you get a group of four new players who you bring onto your team and they’re all team-first, unselfish, competitive, self-motivated players, there’s a decent chance that the chemistry is gonna have a chance to be good,” Buchanan said. “Doing a ropes course, that’s great in theory and may work for a business, but professional athletes, they develop chemistry by knowing they can trust each other because they’ve been together through tough times on the court.”

Searching for answers that don’t exist

Chemistry is worth deep investment, but perhaps it can be overanalyzed, too.

“We try to make the simple complicated at times,” ESPN NBA analyst Jeff Van Gundy said. “Going out to dinner is a far different chemistry than playing chemistry. You read a lot about, ‘We play paintball together.’ Who gives a shit, you know?

“I don’t believe it’s the reason why a team is either good or not good. I think you’ve gotta get great players, and when you have them you gotta try and keep them.”

There are endless ways to cultivate chemistry, but teams can still only guess at what will work in every situation. Statistics aren’t a good guide. They can’t quantify personality flaws or gauge emotional intelligence. When intuition is the best way to make a decision, some front office executives lean too hard on what they can measure instead.

“I think a lot of these GM’s, they really don’t take [chemistry] into consideration,” Utah Jazz center Ed Davis said. “They’re starting to treat the NBA like 2K and more just looking at numbers instead of, ‘are these two players going to get along?’ And I think you’re gonna start seeing GM’s lose their jobs.”

Top-tier skill, athleticism and on-court awareness is very often the bottom line for NBA teams, but those still trying to crack chemistry’s mysteries have good reason to believe they aren’t running a fool’s errand, as vulnerable as their circumstances may make them feel.

“There’s something very powerful about newness,” Shenbaum said. “And if you embrace it early, whether it’s a new coach, five new players, the star left, if you embrace it early you can actually create a very authentic bond.”

Defining chemistry can feel like trying to catch the wind. It is omnipresent and elusive at the same time. Until the NBA’s best and brightest crack the formula, they will have to deal with increasing levels of uncertainty in what was already an uncertain business.

Time will tell if NBA teams ever learn how to overcome their mounting challenges — from the shifting ways teams are built, to how on-court strategy is implemented, to the quality of the game itself. But there’s no denying that chemistry is a force multiplier, complex and intractable. And in an era of basketball that demands urgency more than ever, that fact can be frightening.

A lot of players and teams will continue to fail in familiar ways, well-laid plans crumbling because players, coaches and executives never understood each other on or off the court. Only now, they may not realize their mistakes until they find themselves starting all over. Again.

0 notes

Text

Spurs news Manu Ginobili reveals that a car accident almost killed him back in 2004.

Spurs news: San Antonio Spurs legend Manu Ginobili has left fans with tons of memorable highlights, from fancy layups to clutch baskets that helped the franchise win four NBA titles. The future Hall of Famer decided to call it a career in 2016, and there is no denying that his number will soon be hung in the rafters of the AT&T Center.

But did you know that Ginobili almost died in 2004? Yes, the Argentinian star revealed that he was involved in a car accident that almost ended his life that year.

“In 2004… during my honeymoon, I got a car in the front of me that passed a truck on a curve. I threw myself on the shoulder and began to skid. I could have killed someone. I could have slammed against a tree. I could fallen on a cliff or hit the driver head on. There would have been no Olympic games. There was no more career. It was a flip of the coin in the air. Luck.”

The NBA has seen several careers cut short by accidents, including Drazen Petrovic, Len Bias, and Malik Sealy. Ginobili was fortunate enough to survive and he went on to have a great career with the Spurs.

Ginobili averaged 13.3 points, 3.5 rebounds and 3.8 assists in 1,057 games with the Spurs. He made the All-Star team two times and won the 2008 Sixth Man of the Year Award. He’s also widely recognized as one of the greatest non-American NBA players of all-time. We were fortunate enough to see him play, whether we liked San Antonio or not.

The Spurs built their dynasty around Tim Duncan, Tony Parker, and Ginobili. They each had a ton of contribution in the franchise’s success. Without them, who knows how good San Antonio will be?

There’s still one icon that remains with the Spurs, and that is head coach Gregg Popovich, who recently set the record for the longest tenure in coaching one franchise. Once Pop is gone, it will officially be the end of an era in San Antonio.

Follow ClutchPoints for the latest San Antonio Spurs news and updates.

#NBANEWS #SPURSNEWS

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://toldnews.com/sports/basketball/on-pro-basketball-a-cloudy-future-for-the-n-b-a-s-gold-standard-following-game-7-loss/

On Pro Basketball: A Cloudy Future for the N.B.A.’s ‘Gold Standard’ Following Game 7 Loss

Early in the N.B.A.’s only first-round playoff series that stretched to seven games, it was suggested to Tim Connelly, the Denver Nuggets’ president of basketball operations, that a matchup with the San Antonio Spurs was actually a good thing for his young team.

Facing the Gregg Popovich-led Spurs, Connelly was told, would be like going to Playoff School for Denver, a group that brought the West’s No. 2 seed to the matchup — but virtually no postseason experience.

“They’re the gold standard of the N.B.A., with maybe the best coach of all time,” Connelly countered, shooting down the theory as quickly as he heard it.

“You never want to see the Spurs.”

To Connelly’s delight, Denver went from nearly losing the first two games at home to the uber-prepared No. 7 seed to staring the Spurs down and closing them out Saturday night. In a winner-take-all Game 7, Nikola Jokic (21 points, 15 rebounds, 10 assists) posted another triple-double and the Nuggets hung on for a 90-86 victory. The result was a series that felt like an upset no matter what the regular-season standings said — especially since it ended with Popovich inching onto the Pepsi Center floor during live play in the final seconds and screaming in vain for LaMarcus Aldridge or Patty Mills to commit a foul that never came.

Imagine that: A remedial execution error sealed the Spurs’ second straight first-round ouster. Veterans like Aldridge and Mills shouldn’t have to be told to foul when trailing by 4 points inside the closing 30 seconds.

Not long after Kawhi Leonard rumbled for a decisive 45 points in Toronto’s series-opening victory over Philadelphia, Popovich was thus left to process back-to-back Round 1 exits for the first time in his storied coaching career.

A foul, of course, was unlikely to save the visitors at that stage, with Denver holding a two-possession lead. Yet it was a decidedly un-Spurs-like ending to a first season post-Kawhi that generally exceeded expectations — an ending which, just like that, ushered Pop and Co. to a real crossroads.

After an N.B.A. record 22 consecutive playoff appearances by the Spurs, all overseen by Popovich, all of San Antonio now awaits a firm declaration from the coach synonymous with the Alamo City’s beloved Spurs that he intends to return.

In January, when The New York Times asked him directly if he planned to carry on, Popovich admitted that “I don’t know the answer.”

After the Spurs’ elimination late Saturday, Popovich was asked about his expiring contract and coaching this group next season. He spoke for a full 40 seconds — far longer than he usually grants from the postgame interview podium. His answer, though, included no mention of signing a new deal. Popovich, in fact, didn’t address his status at all, focusing on the fact that the projected return of the injured guard Dejounte Murray ensures that “it won’t be the same team.”

Clarity could be coming this week, perhaps as early as Monday, since Popovich typically conducts one last session with the news media shortly after the Spurs’ final game. Yet there has been no formal update on the matter since our story in January, when Connelly’s San Antonio counterpart, R.C. Buford, would only say: “He’ll coach as long as he wants to coach.”

This much is certain: Popovich is committed to coach the United States men’s national team — his dream job — for the next two summers. It is a commitment that has led numerous league observers to surmise that coaching the Spurs for one more season and walking away after the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo is the most natural scenario.

Yet it must be noted, once again, that there are less than two weeks between the FIBA World Cup in China from Aug. 31-Sept. 15 and the start of Spurs training camp. For just the fourth coach in league history to do this job at age of 70, that would offer an extremely short turnaround.

Hard as it can be to try to read the former Air Force Academy officer who once aspired to a career in military intelligence, it is also natural to wonder whether Popovich still finds the grind sufficiently enjoyable to persist. There have been enough credible rumblings to the contrary over the season to believe that the campaign was much more of a strain than it appeared.

This wasn’t merely the first full season of his coaching life in which Popovich couldn’t lean on Tim Duncan, Tony Parker or Manu Ginobili. It was also Year 1 after Leonard became the first Popovich-era player to force his way out of town via trade.

San Antonio had to overcome the season-ending loss of its top defender in Murray in October, along with an 11-14 start, just to keep its seemingly interminable streak of reaching the postseason intact. In the Denver series, on a personal level, Popovich coached the Spurs to a Game 3 victory at home on the same night that marked the one-year anniversary of his wife Erin’s death after a lengthy illness.

It was ultimately San Antonio’s failure to hold the two 19-point leads it built in Game 2, rather than the chaotic scenes of Game 7 crunchtime, that cost the Spurs their shot at a second-round date with the star of the playoffs so far: Portland’s Damian Lillard. But after the final game, Popovich chose to laud the Nuggets for their breakthrough instead of lamenting the lost opportunity.

“I’m really happy for them in a strange sort of way,” Popovich said.

The Spurs can likewise take solace in the knowledge that, as long as they still employ the shrewd Buford, Popovich can count on a roster to entice him to keep going.

I wrote earlier this season about how the struggles of Manchester United in the English Premier League to replace the iconic Sir Alex Ferguson had to be daunting for Spurs officials and fans as they are increasingly forced to imagine who could successfully succeed Popovich. United is on its fifth managerial successor to Ferguson in six years and England’s 20-time champions still are not sure they have it right.

But the difference between rudderless United and ever-steady San Antonio is the scouting eye of Buford, who found Parker (No. 28) and Ginobili (No. 57) with ridiculously late draft picks and who may have done it again with his two No. 29s: Murray and Derrick White.

White had a dreadful series after his 36-point masterpiece in Game 3, but this essentially was his rookie season. The Spurs look like they have something with the trio of Murray, White and Bryn Forbes — along with two more first-round picks coming in June — and the team could have salary-cap space to spend in the summer of 2020 if they decide to move on from Aldridge and DeMar DeRozan.

Yet there is only one Pop — as Denver Coach Mike Malone repeatedly said these past two weeks. The series started with Malone joking about trying to live up to Pop’s five championship rings with just his “wedding ring.” It ended with the 54-win Nuggets finding a way to survive Playoff School — barely — but not before Malone likened Popovich to Bobby Fischer, the famed chess champion.

“Sometimes things work, and sometimes they don’t,” Popovich said after Game 6 when pressed on strategy. “But I’m probably not going to discuss the plan with you, with all due respect. I’m not sure why I should do that.”

The same clearly applies to his future. This is Gregg Charles Popovich, and whether you like the manner in which he answers reporters’ questions or not, he’ll tell us when he’s ready.

#basketball news college#juco basketball news#n b a basketball news#ncaa basketball news 2018#talk n text basketball news#unc basketball news observer

0 notes

Text

Kawhi Leonard’s Handle is the Secret to his Success

Kawhi Leonard is 27 years old, enjoying the prime of a career that’s already turned him into the most complete basketball player in the world. He can score efficiently at all three levels, shoot, rebound, create for teammates, and, without help, defend just about every player in the league.

But when Phil Handy—an assistant coach for the Toronto Raptors who specializes in skill development and has worked closely with LeBron James, Kobe Bryant, and Kyrie Irving, among many others—met Leonard over the summer and asked what part of his game he most wanted to improve, the two-time Defensive Player of the Year had ball-handling at the top of his list.

“Great players are great players, and I think they become even better players when they’re willing to get out of their comfort zone and just work on different things,” Handy told VICE Sports. “Kawhi was already a good ball-handler. I just think a lot of people didn’t really get to see that part of his game. It was there.”

They started with simple combinations and focused on improving his balance, base, and footwork, then blended in additional moves with multiple variations. Repetition was key. The objective wasn’t necessarily to teach Leonard new ways to transport himself from Point A to Point B on a basketball court so much as it was to plow what he already knew even deeper into his psyche. Now, when Leonard does something with the ball, his reflexes kick in before his brain has time to process what’s going on.

“Sometimes the dribbling exercises you put guys through, it may not be something they actually use on the floor but it gives transference. Their instincts become better,” Handy said. “They just instinctually start to go from one handle to another to another when they’re in different situations in games.”

He’s availing himself with a broader palette. Here’s Leonard getting hounded by Minnesota Timberwolves rookie Josh Okogie. When he goes between his legs and Okogie reaches in for the steal, Leonard spins baseline fast enough to convince viewers the move was directed by a choreographer.

The result of Leonard’s hard work during the offseason is clear every night. After a lost year in which he only appeared in nine games, Leonard has not only re-inserted himself into MVP and “best player alive” debates, but has also emerged in his first year with the Raptors as arguably the best ball-handler at his position. Plays like the one seen below are already typical.

On the San Antonio Spurs, Leonard’s handle felt like a pencil sketch of the Mona Lisa. Greatness was imminent, but operating in place of flair and spectacle was a robotic efficiency that never really needed to evolve. Every dribble inside Gregg Popovich’s system was a wasted opportunity to pass or shoot, and who was to argue with that calculus? His straight line drives regularly led to tomahawk dunks. The Spurs were a juggernaut. That doesn’t mean Leonard was stagnant, though. He itched to journey past the fundamentals which had already been mastered. There was strobe-light training and a demand to create more than separation for his own shot, particularly in the playoffs, as Tim Duncan, Tony Parker, and Manu Ginobili aged out of their responsibilities.

“He always was able to get to his spots, but now he is so comfortable anywhere,” Jamal Crawford told VICE Sports. “His handle is to the point where he does things to hop into shots, along with getting to the rim, along with using it to get his space in the mid-range.”

Today, Leonard’s ball-handling is an ideal marriage between style and substance; it’s grown from garnish to bedrock. There’s more fluidity and jazz at a higher volume. His dribbles per touch are at a career high, and shots attempted after at least three dribbles account for over 57.2 percent of his own offense. (Two seasons ago that was 42 percent, and one before that it was 37.1 percent.) Leonard is also averaging 5.3 more drives per game than he did three years ago, and 1.5 more than his last healthy season with the Spurs. (So far, only 36 percent of Leonard’s shots have been assisted. His previous career low was 48 percent, and in his third year that number was all the way up at 59 percent.)

“San Antonio did a phenomenal job developing Kawhi and helping him become a better player. I just think it was a different system.” Handy said. “The flow of our offense puts him in different situations where he’s able to expand a little bit more.”

The hard work is paying off, but a change of scenery hasn’t hurt. When I asked why he’s been able to showcase his ball-handling a bit more this season than in year’s past, Leonard acknowledged Toronto’s system and how he’s being utilized: “It’s pretty much just the offense that we’re running. I’m just able to come off pin downs and there’s a lot of cross screens and dribble hand-offs. Nick’s just doing a good job of spacing out the floor.”

Where lineups earlier in his career rarely prioritized offensive gravity over defensive intimidation, Leonard now operates with four three-point shooters by his side (including Pascal Siakam, who’s making a relatively impressive 34.6 percent of his threes right now), in an era designed for stars to take advantage of extra room. When he receives a pick high above the three-point line, Leonard skis downhill and sticks the screener’s defender on an island. It’s impossible to guard, but switching isn’t much of an alternative.

“We knew he could score in and out and off screens and all those kind of things. Play in transition some. And now we’re kind of getting him more in the screen-and-roll game, so he’s learning. And I think he’s starting to see things a little bit better too. He’s finding some kick-outs and passes out of there, and those guys are gonna need to step in and make them,” Raptors head coach Nick Nurse said. “So he can do everything, right? He can do everything, and we’ll just keep progressing with keeping it in his hands in all situations.”

Sit 15 feet away when he warms up at the free-throw line, as I did before a recent Raptors game, and it’s impossible to ignore just how small everything looks in his hands—if the basketball is Earth’s surface, Leonard’s hands are its oceans. At the NBA combine in 2011, his hands were 11.25 inches wide—which is wider than every player measured at the last four combines—and served as exclamation points at the tip of his 7’3” wingspan. They’ve always been his closest friends, around to help deflect passes and tally unreachable steals, sky for a rebound or finish a contested layup. And now more than ever, it’s hard to negate their usefulness when he handles the ball, too.

“Kawhi is really long, so my tendency when I’m working with guys that are long is to help them tighten their handle,” Handy said. “It makes sense biomechanically with your body, if you’re sitting in a wider stance it’s going to help you keep your length in.”

Leonard has more control over his entire body than the average person does over their big toe. Merge that discipline with unparalleled physical dimensions that directly impact his ability to manipulate a basketball, and what you get is a unique handle that defenses can’t really stop. He’s even more compact and under control than he used to be, which, when talking about someone who already takes care of the ball better than any star in the league, is really saying something. It allows him to alter tempos whenever/wherever he wants.

“He doesn’t play at a breakneck speed, but when he changes speeds he’s fast,” Handy said. “He just kind of puts you to sleep with the way he plays, and then boom. He’s really deceptive like that.”

The first time I re-watched this video, I thought the fourth dribble was a glitch; I’m still not 100 percent positive the ball physically travels went between his legs:

Already one of world’s best players, Leonard’s growth in this specific area has elevated his ceiling and made it even less possible to slow him down. Try and trap him and he’ll turn the corner, draw two defenders and still create enough space for a baseline fadeaway. Leonard regularly rips the ball off the rim and goes coast-to-coast, swiveling through defenders with an in-and-out move that’s executed to perfection at top speed. His between-the-legs crossover is lightning and his one, two, three-dribble pull-ups are virtually unguardable. Leonard’s handle isn’t the entree of his skill-set, but it complements everything else that makes him a franchise-altering talent. And just like every other gem who thrives in the same rarefied tier, the best is yet to come.

“I don’t care who you are, Kyrie, Steve Nash, Chris Paul. I don’t think you ever get to a point in your career where you say ‘OK, that’s enough with my ball-handling,’” Handy said. “You always have to constantly continue to get the rhythm of the basketball, and keep your handles tight, so wherever you are on the floor there’s any combination of dribbles you can use.”

Kawhi Leonard’s Handle is the Secret to his Success syndicated from https://justinbetreviews.wordpress.com/

0 notes

Text

Kawhi Leonard's Handle is the Secret to his Success

Kawhi Leonard is 27 years old, enjoying the prime of a career that’s already turned him into the most complete basketball player in the world. He can score efficiently at all three levels, shoot, rebound, create for teammates, and, without help, defend just about every player in the league.

But when Phil Handy—an assistant coach for the Toronto Raptors who specializes in skill development and has worked closely with LeBron James, Kobe Bryant, and Kyrie Irving, among many others—met Leonard over the summer and asked what part of his game he most wanted to improve, the two-time Defensive Player of the Year had ball-handling at the top of his list.

“Great players are great players, and I think they become even better players when they’re willing to get out of their comfort zone and just work on different things,” Handy told VICE Sports. “Kawhi was already a good ball-handler. I just think a lot of people didn’t really get to see that part of his game. It was there.”

They started with simple combinations and focused on improving his balance, base, and footwork, then blended in additional moves with multiple variations. Repetition was key. The objective wasn’t necessarily to teach Leonard new ways to transport himself from Point A to Point B on a basketball court so much as it was to plow what he already knew even deeper into his psyche. Now, when Leonard does something with the ball, his reflexes kick in before his brain has time to process what’s going on.

“Sometimes the dribbling exercises you put guys through, it may not be something they actually use on the floor but it gives transference. Their instincts become better,” Handy said. “They just instinctually start to go from one handle to another to another when they’re in different situations in games.”

He's availing himself with a broader palette. Here’s Leonard getting hounded by Minnesota Timberwolves rookie Josh Okogie. When he goes between his legs and Okogie reaches in for the steal, Leonard spins baseline fast enough to convince viewers the move was directed by a choreographer.

The result of Leonard's hard work during the offseason is clear every night. After a lost year in which he only appeared in nine games, Leonard has not only re-inserted himself into MVP and “best player alive” debates, but has also emerged in his first year with the Raptors as arguably the best ball-handler at his position. Plays like the one seen below are already typical.

On the San Antonio Spurs, Leonard’s handle felt like a pencil sketch of the Mona Lisa. Greatness was imminent, but operating in place of flair and spectacle was a robotic efficiency that never really needed to evolve. Every dribble inside Gregg Popovich’s system was a wasted opportunity to pass or shoot, and who was to argue with that calculus? His straight line drives regularly led to tomahawk dunks. The Spurs were a juggernaut. That doesn’t mean Leonard was stagnant, though. He itched to journey past the fundamentals which had already been mastered. There was strobe-light training and a demand to create more than separation for his own shot, particularly in the playoffs, as Tim Duncan, Tony Parker, and Manu Ginobili aged out of their responsibilities.

“He always was able to get to his spots, but now he is so comfortable anywhere,” Jamal Crawford told VICE Sports. “His handle is to the point where he does things to hop into shots, along with getting to the rim, along with using it to get his space in the mid-range.”

Today, Leonard’s ball-handling is an ideal marriage between style and substance; it’s grown from garnish to bedrock. There's more fluidity and jazz at a higher volume. His dribbles per touch are at a career high, and shots attempted after at least three dribbles account for over 57.2 percent of his own offense. (Two seasons ago that was 42 percent, and one before that it was 37.1 percent.) Leonard is also averaging 5.3 more drives per game than he did three years ago, and 1.5 more than his last healthy season with the Spurs. (So far, only 36 percent of Leonard’s shots have been assisted. His previous career low was 48 percent, and in his third year that number was all the way up at 59 percent.)

"San Antonio did a phenomenal job developing Kawhi and helping him become a better player. I just think it was a different system." Handy said. "The flow of our offense puts him in different situations where he’s able to expand a little bit more."

The hard work is paying off, but a change of scenery hasn’t hurt. When I asked why he’s been able to showcase his ball-handling a bit more this season than in year’s past, Leonard acknowledged Toronto’s system and how he’s being utilized: “It’s pretty much just the offense that we’re running. I’m just able to come off pin downs and there’s a lot of cross screens and dribble hand-offs. Nick’s just doing a good job of spacing out the floor.”

Where lineups earlier in his career rarely prioritized offensive gravity over defensive intimidation, Leonard now operates with four three-point shooters by his side (including Pascal Siakam, who's making a relatively impressive 34.6 percent of his threes right now), in an era designed for stars to take advantage of extra room. When he receives a pick high above the three-point line, Leonard skis downhill and sticks the screener’s defender on an island. It’s impossible to guard, but switching isn't much of an alternative.

“We knew he could score in and out and off screens and all those kind of things. Play in transition some. And now we’re kind of getting him more in the screen-and-roll game, so he’s learning. And I think he’s starting to see things a little bit better too. He’s finding some kick-outs and passes out of there, and those guys are gonna need to step in and make them,” Raptors head coach Nick Nurse said. “So he can do everything, right? He can do everything, and we’ll just keep progressing with keeping it in his hands in all situations.”

Sit 15 feet away when he warms up at the free-throw line, as I did before a recent Raptors game, and it’s impossible to ignore just how small everything looks in his hands—if the basketball is Earth's surface, Leonard’s hands are its oceans. At the NBA combine in 2011, his hands were 11.25 inches wide—which is wider than every player measured at the last four combines—and served as exclamation points at the tip of his 7’3” wingspan. They’ve always been his closest friends, around to help deflect passes and tally unreachable steals, sky for a rebound or finish a contested layup. And now more than ever, it’s hard to negate their usefulness when he handles the ball, too.

“Kawhi is really long, so my tendency when I’m working with guys that are long is to help them tighten their handle,” Handy said. “It makes sense biomechanically with your body, if you’re sitting in a wider stance it’s going to help you keep your length in.”

Leonard has more control over his entire body than the average person does over their big toe. Merge that discipline with unparalleled physical dimensions that directly impact his ability to manipulate a basketball, and what you get is a unique handle that defenses can’t really stop. He’s even more compact and under control than he used to be, which, when talking about someone who already takes care of the ball better than any star in the league, is really saying something. It allows him to alter tempos whenever/wherever he wants.

“He doesn’t play at a breakneck speed, but when he changes speeds he’s fast,” Handy said. “He just kind of puts you to sleep with the way he plays, and then boom. He’s really deceptive like that.”

The first time I re-watched this video, I thought the fourth dribble was a glitch; I’m still not 100 percent positive the ball physically travels went between his legs:

Already one of world’s best players, Leonard’s growth in this specific area has elevated his ceiling and made it even less possible to slow him down. Try and trap him and he'll turn the corner, draw two defenders and still create enough space for a baseline fadeaway. Leonard regularly rips the ball off the rim and goes coast-to-coast, swiveling through defenders with an in-and-out move that's executed to perfection at top speed. His between-the-legs crossover is lightning and his one, two, three-dribble pull-ups are virtually unguardable. Leonard's handle isn't the entree of his skill-set, but it complements everything else that makes him a franchise-altering talent. And just like every other gem who thrives in the same rarefied tier, the best is yet to come.

“I don’t care who you are, Kyrie, Steve Nash, Chris Paul. I don’t think you ever get to a point in your career where you say ‘OK, that’s enough with my ball-handling,’” Handy said. “You always have to constantly continue to get the rhythm of the basketball, and keep your handles tight, so wherever you are on the floor there’s any combination of dribbles you can use.”

Kawhi Leonard's Handle is the Secret to his Success published first on https://footballhighlightseurope.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

SAN ANTONIO | Ginobili content with retirement after 16 seasons with Spurs

New Post has been published on https://www.stl.news/san-antonio-ginobili-content-with-retirement-after-16-seasons-with-spurs/170635/

SAN ANTONIO | Ginobili content with retirement after 16 seasons with Spurs

SAN ANTONIO — Manu Ginobili walked into the San Antonio Spurs practice facility and saw the intense efforts of his young teammates in preseason workouts.

Ginobili had put himself through those same workouts for 16 seasons. But this August morning, the 41-year-old realized he couldn’t. For a player who has literally thrown himself into his basketball career, the realization his body and spirit were no longer willing cemented the decision to walk away from the NBA.

“I couldn’t see my body going through that kind of grind again,” Ginobili said Saturday during a press conference at the Spurs practice facility. “I felt that I had a good season, that I left everything that I had in the previous season both physically and mentally.”

Ginobili was thoughtful, self-effacing and funny in his first interview since announcing his retirement Aug. 27 on social media. He steps away after helping San Antonio win four of its five NBA titles, the last coming in 2014.

His retirement, along with Tony Parker’s departure to the Charlotte Hornets as a free agent, brings an end to the era of the Spurs’ Big Three. Along with Tim Duncan, Ginobili and Parker helped San Antonio become the most successful franchise in any sport based on winning percentage.

The Spurs also will be without Kawhi Leonard, who requested a trade and was dealt to Toronto along with Danny Green for DeMar DeRozan and Jakob Poeltl. It will be the first time coach Gregg Popovich enters a season without one of the Big Three by his side.

“I think it’s going to be a great challenge for him having a different kind of team, maybe less corporate knowledge,” Ginobili said. “I think it’s going to be a fun challenge. I think he’s going to do good.”

The Argentina native was twice selected to the All-Star team and twice named to the All-NBA third team despite spending most of his career coming off the bench. He was named the 2008 NBA Sixth Man of the Year.

“Playing 16 years is completely unexpected and going through everything we went through,” Ginobili said. “Big disappointments, huge wins, creating that type of union with the coaching staff, with the front office, with the staff, teammates . it’s been an amazing journey, way beyond anything that can be expected.”

Ginobili played professionally in Argentina and Europe for seven seasons before joining the Spurs in 2002 following his selection with the 57th pick in 1999. He entered the NBA as a mop-topped 25-year-old who could make a spectacular pass one minute and then throw the ball into the stands the next. Ginobili’s dynamic, if erratic, plays endeared him to fans but caused consternation for Popovich.

But his coach grew to love and accept Ginobili’s unique abilities.

“As time went along, I learned to not speak if I thought a shot was contested or if there was a defensive play he wanted to make to get a steal because he does things that win games,” Popovich said. “So, it taught me to watch a little more and not be so micromanagement like.”

His willingness to put team first also endeared him to Popovich and the fans. Despite averaging 13.3 points, 3.8 assists and 3.5 assists in his career, Ginobili only started 349 of 1,057 career games.

Accepting a role off the bench was difficult for a player as competitive as Ginobili, especially since his goal was to be an NBA starter.

“Never did (achieve that),” Ginobili said, laughing. “I actually achieved it in my game two or game three. I said ‘Yes,’ then boom, back to the depths of the bench. At the beginning it was kind of hard. It took me a while to understand it, to get my ego out of the middle between Pop and me, or the game and me, and how that had to be done for the team and me.”

Coming off the bench only cemented Ginobili’s legacy. His selflessness, along with a Eurostep drive to the basket he helped popularize, will surely lead to a place in the Hall of Fame.

In addition to his NBA success, Ginobili won a championship in the Euroleague and Italian league and led Argentina to gold in the 2004 Athens Olympics.

Ginobili reflected on all that success and all those memories last season, knowing it would be his last. Although he “left the door open” for a possible return this season, Ginobili said nothing changed his mind.

“Even though I was, I am very sure about the decision, it’s still awkward,” Ginobili said. “It’s still tough. You are convinced, you talk to your wife, you know what you’ve got to do. But my finger shaked a lot before hitting that enter (to announce his retirement). It wasn’t an easy decision.”

By RAUL DOMINGUEZ, Associated Press

#16 seasons#Ginobili content#Ginobili had#manu ginobili#practice facility#retirement#San Antonio#Spurs#TodayNews

0 notes

Link

Following Manu Ginobili's retirement, the Spurs dynasty appears to be over. The run started in 2003, with an all-time classic team that would go on to win four championships together.

The San Antonio Spurs run finally appears to be over, or at least close to it.

After Manu Ginobili retired on Monday, only Gregg Popovich remains of the original Spurs' dynasty. Tony Parker left in free agency this year, and Tim Duncan retired in 2016.

The core of Duncan, Ginobili, Parker, and Pop formed in 2002 when Ginobili entered the NBA. That 2002-03 Spurs team went onto win a championship, the first of four that the four men would share together.

But that team has plenty of other big names on it, too, from former All-Stars, legendary role players, notorious coaches, and more.

Here's where the 2002-03 Spurs team is today.

Tim Duncan was the leader of the Spurs. He averaged 23 points, 13 rebounds, and 4 assists per game that season en route to MVP and later, Finals MVP.

Duncan retired in 2016 after winning three more championships en route to becoming the Spurs' greatest player and one of the best players in NBA history. Today, he still works with the franchise in an unofficial capacity.

Tony Parker was just 20 years old and in his second NBA season, but he took over as the full-time starting point guard, averaging 15 points and 5 assists per game.

Parker, 36, left the Spurs after 16 years this offseason and signed with the Charlotte Hornets.

Manu Ginobili joined the Spurs in 2002-03, though he was drafted in the second round in 1999. After a decorated international career, the 25-year-old Ginobili averaged just 7 points in 20 minutes per game in his first year.

Ginobili retired on Monday at the age of 41. With career averages of 13 points, 3 rebounds, and 3 assists per game, Ginobili is the only non-American player to win four NBA championships and an Olympic gold medal. He's a sure-fire Hall of Famer.

David Robinson, once the Spurs' franchise player, still manned the middle next to Duncan in 2002-03. He averaged 8 points and 8 rebounds per game that season.

Robinson retired after the 2003 championship. He was a 10-time All-Star and the 1995 MVP. He is now a co-founder of Admiral Capital Group, a real estate and private equity firm.

Bruce Bowen was the Spurs' lockdown defender. He made the All-Defensive Second Team that season.

Bowen retired with the Spurs in 2009. He has since worked as an analyst for ESPN and worked with Fox Sports for the 2017-18 season covering the Los Angeles Clippers. He reportedly lost his job this offseason for making critical comments about Kawhi Leonard, a target of the Clippers.

Source: ESPN

Stephen Jackson was a talented wing who alternated between the starting lineup and coming off the bench that season, his third in the league.

Jackson retired in 2014 after playing for eight teams in 14 years. He has since worked as an NBA analyst and now plays in the Big3.

Steve Kerr, then 37, came off the bench and gave the Spurs a veteran presence. His highlight moment came in the Western Conference Finals when he scored 12 points off the bench to give them a big win.

Kerr retired the next season after 15 years in the NBA. He was a GM for the Phoenix Suns, then an NBA analyst for TNT. He now coaches the Golden State Warriors.

Malik Rose was an effective big man off the bench for the Spurs, averaging 10 points and 6 rebounds per game.

Rose played for four teams in 13 years, retiring in 2009. After working as a color analyst for the 76ers, Rose was the GM of the Erie Bayhawks of the G League. This offseason, he was hired as assistant GM of the Pistons.

Steve Smith, then 33, came off the bench for the Spurs, averaging 7 points in 19 minutes per game.

Smith made one All-Star team in his 14-year career. He's now an analyst for NBA TV.

Danny Ferry came off the bench for the Spurs that year, his 13th in the league, playing a very limited role.

After playing in the NBA, Ferry became a successful executive with Cavaliers and Hawks. In 2015, he split ways with the Hawks following an investigation into whether he made a controversial, race-related comment about a player; he was absolved of any wrongdoing. He is now an advisor to the Pelicans.

Speedy Claxton was a second-year guard who came off the bench behind Tony Parker. Despite a smaller role with the team, he had a big Finals game that helped the Spurs seal the championship.

Claxton would play five more years in the NBA, retiring in 2009. He is now an assistant coach for Hofstra.

Kevin Willis was a 40-year-old big man who came off the bench for the Spurs.

Willis played until he was 44, retiring in 2007. He is tied for most seasons in the NBA. Since retiring he has started his own clothing line called Willis & Walker and appeared on NBA TV as an analyst.

Source: NBA.com

Mengke Bateer was a reserve big man who came over from China. He played just 44 total in minutes during the season.

Bateer left the NBA in 2004 and returned to China. He retired in 2015.

Gregg Popovich was in his seventh year as head coach of the Spurs.

Popovich, of course, is still with the Spurs. He has a career 1197-541 career record.

P.J. Carlesimo was an assistant coach with the Spurs, his first coaching job following an infamous altercation with Latrell Sprewell while with the Warriors.

Carlesimo stayed with the Spurs until 2008. He had several other jobs, including head coach of the Nets from 2011-2013. He is now an NBA and college basketball analyst.

Mike Budenholzer was in his seventh year as an assistant coach with the Spurs.

Budenholzer stayed with the Spurs until 2013, when he became head coach of the Hawks. Budenholzer made the playoffs four times with the Hawks and was hired as head coach of the Bucks this offseason.

Mike Brown was in his third year as an assistant coach with the Spurs.

Brown would go on to become head coach of the Cavaliers for five years. He has a 347-216 record as a head coach. He's been an assistant with the Warriors for the last two years, even acting as interim head coach when Steve Kerr had to miss time with back pain.

Joe Prunty was an advanced scout for the Spurs that year after working as a video coordinator.

Prunty has served as an assistant coach with the Mavericks, Blazers, Cavs, Nets, and Bucks. After taking over as interim head coach with the Bucks last year, he joined the Suns as an assistant coach this offseason.

Now, check out what has happened to college football stars...

WHERE ARE THEY NOW? The last 20 Heisman Trophy winners >

via Nigerian News ➨☆LATEST NIGERIAN NEWS ☆➨GHANA NEWS➨☆ENTERTAINMENT ☆➨Hot Posts ➨☆World News ▷NEWS

#IFTTT#Nigerian News ➨☆LATEST NIGERIAN NEWS ☆➨GHANA NEWS➨☆ENTERTAINMENT ☆➨Hot Posts ➨☆World News ▷NE

0 notes

Text

After Years of “Hard Work” at Comedy, It’s Okay to be Tired

A month ago, I had to help my partner lift an armoire she purchased from a thrift store into her new home. We watched three volunteers at the thrift store glide the armoire into the U-Haul using a dolly. Yet at that point it hadn’t dawn upon us how much of a nightmare moving that armoire would be for just two people. It was the worst experience I’ve ever had moving anything. It took an hour, the creation of our own ramp out of a piece of wood we just happened to have, a lot of silence mixed with arguing, and each of us nearly accidentally murdering the other with the armoire, but it finally got into the home. We celebrated with Dairy Queen blizzards. But the whole situation made me realize two things. First, I am out of shape. And, second, how we all define “hard work” is very bizarre. There is a lot of “hard work” to do in stand-up comedy but I’d take that 100% of the time over having to lift armoires on a daily basis to pay my bills.

I suppose to others I could be defined as a hard worker in stand-up comedy. As I started doing it in 2006 and progressed, I certainly prided myself off of that. I managed that progression while also working a job in an office and leading an active lifestyle. I feel like I have a good life now and I wouldn’t be in the position that I am in if it hadn’t been for the efforts I made since day one in doing comedy.

In 2006, comedy was different. I started in Columbus, which is not by any means perceived to be a mecca of comedy. At that time, comedy wasn’t as appealing as it seems to be today. There were few, if any, podcasts, no Twitter, no Instagram, no Snapchat, and there was a system and structure in place (all be it a still problematic structure) to at least ascend as a stand-up comedian and make it a career. In Columbus, we only had two open mics. So, I did both those open mics while also trying to do and create as many stages as possible for myself and the other comedians in the city. There was no discrimination or judgment. I’d perform at punk bars like Bernie’s or gay bars like Score Bar or suburban shitshows like Junction Bar in Hilliard. That last one was on Cemetery Road so my friend Justin Golak once said of it, “this is where comedy comes to die.” Hitting every stage possible given what limited opportunities there were involved, I suppose, hard work and determination.

Hard work came in the form of all aspects of life. I hit every stage I possibly could. I worked my office job, promising myself I’d never call off work because of comedy (I never did, only once oversleeping and coming in late because of a show) and navigating what little vacation days I had to do shows out of town while getting very limited sleep. I guess I also “played hard” taking advantage of the vices of booze and food that can come with being out at bars in your 20s as a comedian. I did it all and maybe it was part addictive qualities within me and part therapeutic to lead this type of lifestyle. Either way, I sacrificed aspects of my health and even some relationships to give my all to both comedy and life. The flip side of feeling like I gave so much was to also feel negatively towards my surroundings. Despite putting in a lot of effort, I never thought I did enough and could have done more and likewise would be disappointed in peers who I felt didn’t live up to giving their all as well to comedy.

I never discussed my “hard work.” I never felt that was appropriate. It was important to me to just do the job in whatever capacity it may have been and do it to the best of my ability. It wasn’t until 9 ½ years that I felt I could reflect on that and kind of open up that I did give a lot to comedy and it paid off and that was only in a Facebook post about the one-year anniversary of my album recording.

Here we all are after a hard night of working at comedy.

Times change, though. Now comedians regularly post about “hard work” and the amount of stage time they are doing. It doesn’t particularly matter in an era where people are posting and bragging about everything but perhaps it fulfills something for them to tell people of their “grind.” But there’s no way of quantifying such posts. We can look at Malcolm Gladwell’s “10,000 hour rule” as an accurate concept but, in comedy, if the 10,000 hours aren’t done in different environments and are done with no analysis, then it is simply time consumption. If someone says they did 22 sets in a month, that’s great, but if they did the same 22 sets in the same venue, what exact purpose does that serve other than to make them a better comedian with that one set in that one venue?

My point here is that I tried to do it all without any statistics other than to say that for many years I performed, as Travis Bickle once said, “anytime, anywhere.” I still feel a pride and confidence in trying to be a swingman in stand-up comedy and someone that hopefully anyone could plug in a comedy lineup anywhere and I could make the crowd laugh. That’s come from doing shows at some of the bars I mentioned to a kid’s birthday party to a retirement home.

Other than the 10,000 hours mark, there is something to the comment of many comedians that it takes 10 years of hitting stages to be a good comedian. For me, at least, the 10-year mark was important. I can’t explain why but I felt more confident and happy with comedy. I grew more relaxed about whatever the outcome of each show is or what my life in comedy ends up being when it is all said and done. Some of that was also due in part to changes I made when I turned 30. I stopped drinking. I took on more responsibilities with my office job and had flexibilities with it that made me enjoy it even more. All this “hard work” had come to a point where I now lead a solid life and one I have to constantly remind myself is far better off than the extremely depressed, unemployed 21-year-old that first hit the stage at the Scarlet & Grey Café.

I was back in Cleveland this past week. My parents have become used to me visiting but also going out to shows at night. I’ve written a lot of new material over the past month so I really wanted to test it out outside of L.A. I did a show in Akron and in Cleveland last week as well as a couple when I was visiting Columbus again. But, last night, I was scheduled to do a show in Lakewood, which was another one I could just pop on while I was in town so I could continue to test out this new material. And I decided not to. It was my last night in town and I wanted to spend time with my parents. That’s what I felt over 10 years of doing comedy has earned me now. I’d hit so many stages and tested out new material on so many nights. But now, especially since I don’t live in Ohio anymore, I wanted to hang out with my parents. I wanted to see my aunt and uncle who happened to be in town. New material comes and goes and I’ve done this long enough to know there will be plenty more nights I can test that out. Rather than focus on this new material on every night, I’d rather maintain the loving relationships I have left in the time that I can have them.

One of my favorite parts of Louie which I’ve mentioned here before is in the episode, “Bully.” Louie tracks down a teenager who harassed him on a subway and then has a discussion with the kid’s father outside of the family’s home. At one point, when discussing what they do for a living, Louie says “comedian” and says “it’s a job,” and the father responds, “no, it isn’t.” It cracked me up a lot at the time I first watched it and still does now because I, and many of my other fellow comedians, have worked jobs while trying to make a career out of comedy and there’s so much absurdity to comedy and being an entertainer that makes it unbelievable that it could be a job. But comedy is certainly a job and the longer that you do it, the more it becomes one, and the more it becomes part of one’s life which is both amazing and complicated.

I get up for my job at 5 AM. I work from home with little to no social interaction with anyone. I try to exercise. I eat. I may take a nap. I go out to comedy or do something involved with comedy at night if possible. Maybe, on occasion, I take a night off just to relax and watch Netflix. I could complain because the days are long or my life can be lonely or comedy, like so many other artistic dreams, is filled with ups and downs and frustration, but why should I? I worked to get to this point and I’m happy to be there and consider myself lucky to be there.

A lot of comedians like to post about the levels of “hard work” that they go to or compliment someone else on their “hard work.” But, at this point, I think many of us that have been doing it as long as I have or longer have shown that we work hard and we can also express that we are tired, too. I’m willing to admit that after 10 years of really working at comedy and continuing to work at comedy that there is nothing wrong with taking a night off. There is nothing wrong to accepting that time advances and that I have to shift what I’m doing with my body and my life to continue my path in comedy. When a person has stand-up, a job, a relationship, and staying in tune with social media related to comedy (which has now become equally dramatic and emotional for anyone’s mind), it can understandably become an exhausting experience.

I’ve written before about the San Antonio Spurs. The Spurs started a trend a few years ago of resting their veteran players like Tim Duncan, Tony Parker, and Manu Ginobili for random games throughout the season even when they were not injured. Now many teams and players do it. It annoys NBA players of other eras and even some pundits. I understandably think it’s annoying if it happens during a marquee, televised game but the ultimate goal for the Spurs is to win the NBA title. If a random rest day for their players makes it more likely that they accomplish that then that is the smart decision.