#this is part of a much bigger monstrous piece of fiction i wrote

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

hero x villain

“You know, at this point I think you just cause trouble in these woods because you want to see me.” The hero said boredly as she caught the villain and a squad of soldiers about to raid a village. The soldiers all looked cold and were shivering and complaining. The hero had heard their muttering from a league away.

Upon seeing her, they bared their teeth and raised their swords but the villain just smiled and raised his hand to stop them. “Be civil, comrades. Go surround the town and wait for my call. I’ll handle the beautiful lady.”

The soldiers on their horses shuffled off.

The villains got off his horse gracefully. Everything he did was graceful and carefully deliberated, even the smile he sent her way.

“Would it be so wrong of me to wish to seek you out? I have yet to see that beautiful face you’re always bragging about.” He smirked, gesturing to the mask on the hero's face.

“Go away.” The hero said, unamused. “And take the brutes with you and out of my woods.”

“Your woods?”

“My woods.”

He chuckled. “And who crowned you the grand protector of the woods?”

“I did.”

“Come on, it's just one village.” He said, nearly sounding like an insolent child asking for one more minute outside past sundown.

“And? These people did nothing wrong.” The hero reminded him, leaning back against a tree.

“The Emperor thinks they’re harboring fugitives — ”

“They probably just made a poster of him and gave him a really ugly mustache.”

He allowed a smile. “Well, you’re…probably... not wrong.”

“And sending his most powerful asset to do such petty work? I don’t believe it.”

“I volunteered. I was bored.” He shrugged.

“So you did want to see me!” She smirked.

“I never said I didn’t.” He pointed out.

“You’re so obsessed with me that I might ask you to dinner.”

“After you beat me up and give me another bruised rib?”

“Exactly, honey. See? You’re learning.”

“I really don’t see why this is necessary. Can we just skip to the part where you actually take me to dinner?”

“And you poison my food? No, thank you.” The hero snorted. “You’re the villain and I’m the hero who’s going to kick your butt. That’s the way of the world. It’s the cards we’ve been dealt.”

“Excuse me? If anything, I’m the hero and you’re the villain.”

“There is no way you actually believe that.” The hero said, deadpan.

“Don’t heroes serve rulers?”

“Not the competent ones.”

“See, every time I see you I get a bruised rib and bruised pride. That’s not particularly hero-like behavior.”

“I think that’s a you problem. Most people find me rather delightful. Just leave if you want to skip the me beating you up part.”

“What if I don’t want to skip the you beating me up part?”

The hero blinked. “You’re annoying, you know?”

“Mhm.”

“Just let the village alone.”

His dark eyes flashed. “Make me.”

#from my wip#writeblr#enemies to lovers#writing#my writing#creative writing#this is part of a much bigger monstrous piece of fiction i wrote#like 300 pages of epic fantasy you guys i can't 😭#i need motivation to edit it#and my dumbass decided to make it part of a four book series. four books. i'm going to have a meltdown.#anyway please don't steal this i can't handle confrontation 🥺 i'm a smol bean who can't even order a coffee#love you darlings <3#villain x hero#villains and heroes#hero#hero x villain#romance#forbidden love

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Empire of the Vampire Makes Vampires Scary Again

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

This article is sponsored by As a species, humans have more or less always been obsessed with vampires. (The earliest references to blood-drinking creatures date back to ancient Mesopotamia, believe it or not.) But the way we relate to these creatures has shifted throughout the centuries, as legends, folklore, and popular culture have adapted to the needs and fears specific to respective societies.

Published in 1897, Bram Stoker’s Dracula may have sparked a particular vein of horror story that continues to this day (looking at you, American Horror Story: Double Feature), but Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire, published in 1976, changed how audiences relate to bloodsuckers forever and plenty of contemporary vampire tales have continued to cast the creatures as broody, desirous, long-suffering anti-heroes burdened by the weight of immortality.

But don’t expect bestselling Australian author Jay Kristoff’s new book, Empire of the Vampire, to follow this modern trend. In this story, the first in a new epic fantasy trilogy, vampires are 100% terrifying again, vicious monsters who kill violently and indiscriminately, and whose powers mean that few humans are capable of standing against them for long.

“When I was a kid, vampires were the monsters under the bed. They were the scary things that were trying to eat the good people,” Kristoff explains during a wide-ranging conversation with Den of Geek. “I grew up reading books like Salem’s Lot and watching films like The Lost Boys and Near Dark. Those were the vampires that I grew up with.”

Those aren’t generally the sorts of vampires we tend to see in much contemporary fiction nowadays, however. From The Vampire Diaries and True Blood to the Twilight franchise, recent mainstream pop culture has embraced the idea of the vampire as a version of the ultimate bad boy boyfriend, a secretly romantic figure still searching for true love after centuries of loneliness.

“Over the course of the last 20, 30 years they have evolved into something very different,” Kristoff says. “[And] there’s nothing wrong with exploring that kind of vampire,” he adds, describing himself as a “massive fan” of The Vampire Diaries and firmly “Team Delena” when it comes to the love triangle at the show’s center.

“The cool thing about [the ‘vampire’ concept] is they’re a dozen different things to a dozen different people. You can have a dozen different vampire fans in the room, and they’ll all tell you a different reason why they like them, why they’re attracted to them.”

Though Kristoff may enjoy the world of The Vampire Diaries—he’s currently making his way through its spin-off The Originals—Stefan and Damon Salvatore were not the sort of creatures whose story he was interested in exploring in Empire of the Vampire. The novel is set in a kingdom where the sun has barely shone for nearly three decades, the dead walk during the daytime, and vicious vampire factions fight for control over the remaining human territories. Its world is bleak and frightening, and his vampires reflect that fact.

“I did want to make them monsters again,” Kristoff says. “I wanted to explore the way eternity and immortality would just warp you beyond all recognition. [How] it would make you inhuman.”

The author cites Rice’s aforementioned Interview with the Vampire as “the biggest influence” on this story. “I’ve loved that book since I was a kid,” he says. “And one of the strong themes that permeates that text is that nothing is forever. Everything goes away on a long enough timeline.” Including the humanity of those who were once human. Kristoff’s novel includes something of a nod to Rice’s work, as the story is framed by our primary protagonist recounting the highs and lows of his life to a vampire historian named Jean-Francois, who is our first consistent glimpse into the removed, detached attitude with which these creatures view human beings.

“Over the course of hundreds upon hundreds of years, if you’re killing a person every night, you very quickly stop seeing people as people and start seeing them as food,” Kristoff explains. “That can’t help but affect your worldview and the way that you interact with it. I don’t think you could help but become inhuman …That’s really what the older vampires in this world are. They’re truly alien and truly monstrous. They look at us the same way that we look at the hamburger that we’re about to eat for dinner.”

Empire of the Vampire is not for the faint of heart. Clocking in at over 800 pages, this is a book bursting with darkness of both the literal and the figurative variety. From the cataclysmic event known as “daysdeath,” which literally darkens the sun to violent, to bloody battles between the living and the dead that lead to (multiple) heartbreaking deaths, this is not a story that’s here to coddle its readers or pull any punches, narratively or figuratively speaking.

“There’s only [redacted] named characters—as in major characters—left alive at the end of the book,” Kristoff teases. “Everybody else is dead.”

But as a result, Empire of the Vampire is also genuinely compelling, a rich, layered story that embraces real stakes and wrestles with complex questions about faith, belief, and family, both found and otherwise.

“It’s the biggest book that I’ve written. It’s definitely the hardest book that I’ve written,” Kristoff says, whose previous works include the Nevernight trilogy, another massive fantasy shot through with violence, corruption, and complex stakes. “Now that I’m at the tail end of it, [I think] it’s the best book that I’ve ever written. I’m more proud of this novel than anything I’ve ever written in my life, and that’s against some pretty stiff competition.”

Ostensibly, Empire of the Vampire follows the story of Gabriel de Leon, the last Silversaint, a member of an elite order of warriors who have sworn their lives to the Church in order to defend the world from the encroaching vampire plague. The novel is his reflection upon his own life, told from what feels very much as though it could be the end of it, imprisoned by the very creatures he was once charged with hunting.

Told in split narratives that look back at the beginning of his time as a Silversaint and his final desperate journey to save the world, Empire of the Vampire not only shows us a hero in crisis but one who has forgotten why he wanted to be a hero in the first place.

“[Gabe’s story] is two sides of the same coin,” Kristoff explains. “One, when he’s young and passionate and thinks all the world is good and bright and he can be a positive force in it. And the other one where he’s gotten old and realized that things don’t always work out the way they do in the storybooks.”

Though Gabe was once the sort of hero who tends to have songs written about them, by the time he’s recounting his great deeds to his vampire captors, he’s become more of a “fallen hero” whose story is primarily “about redemption, or at least a reclamation of faith.”

“Faith was something that was really important to him as a young guy,” explains Kristoff, “but terrible things happened to him over the course of his life and he lost his faith, as many of us do. Part of his journey, at least in Empire, is about finding something to believe in. He’s on a pretty destructive path at the start of the book when we meet him, and he’s 32. He doesn’t have a heck of a lot to live for. At least in part, his journey is about finding something that’s bigger than himself, that’s something more than the revenge that he’s driven toward…something worth fighting for.”

That something arrives in the form of a quest. Like so many before him in popular literature, Gabe ultimately finds himself on a search for the Holy Grail, a magical object that is rumored to be able to end daysdeath, and with it, the vampire plague. Whether the Grail is real or not is a spoiler that only those who read the book will find out, but Gabe’s search for it will quite literally change his life and expand the events of the second and third books in this trilogy in new and different ways.

In Empire of the Vampire, Gabe’s hunt for the Grail forces him to reckon with the darkest aspects of his own life as “ a lot of his own sins come back to haunt him.” As an example, Kristoff describes a later chapter in the book (it’s called “The Worst Day” for those who want to skip ahead) as “the hardest chapter I’ve ever written in my life.”

“I think some of the darkness that was happening in the world around me permeated my head and permeated the story,” Kristoff says of a scene in which, as you might have already guessed, something awful happens to a major character. “I wrote that scene and at the end of it I slammed the laptop shut and just pushed it away from me. I didn’t touch it for four days. I couldn’t bring myself to look at it. That’s the heaviest thing I’ve ever written. Even reading it back now, I’m like, ‘Damn, that’s really tough, you bastard.’”

Empire of the Vampire is just the first piece of what is shaping up to be a massive fantasy saga, and its second installment—which Kristoff says he’s writing right now—is set to expand the series’ world even further, introducing us to the matriarchal clans of the western Ossway as well as the dangerous vampires of the Blood du Voch, whose strength makes them especially difficult to kill. But, according to Kristoff, readers shouldn’t be shocked if the sequel turns our understanding of the story we’re reading on its head once more.

“One of the cool things [about Book 2] is you get a second POV. There’s another character that’s imprisoned in the tower and we get their version of events,” Kristoff explains. “You start to realize that maybe Gabe hasn’t been entirely truthful, or maybe he’s just viewing the past and certain people through rose-colored glasses.”

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

In other words: Buckle up. This adventure has only just begun, and plenty of Kristoff’s dark creatures are still waiting in the wings.

Empire of the Vampire hits bookshelves in the U.S. on September 14th, and in the U.K. a week prior. Find out more here.

The post Empire of the Vampire Makes Vampires Scary Again appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/38RMDMa

0 notes

Text

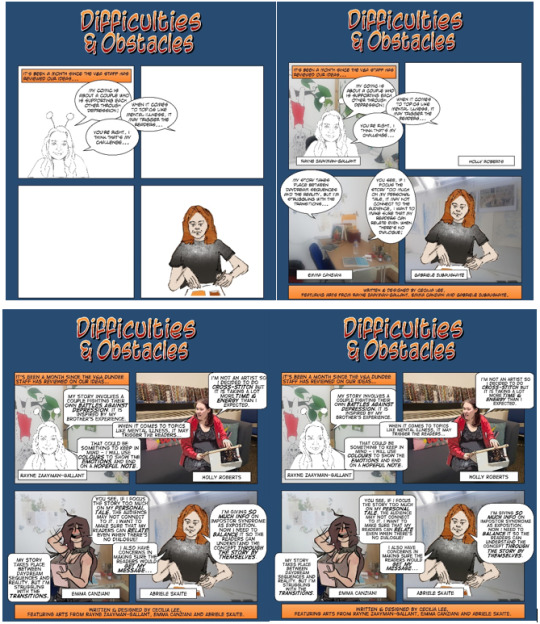

Reflection on Comics Production

As a MLitt student, taking the Comics Production module was a challenging yet meaningful experience. For starters, I have never learned how to draw nor how to use visual editing tools. I did not take the Creating Comics module in the previous semester nor any course on scriptwriting. In other words, I am just a beginner to the comic scene. Therefore, I was thrilled when the module started.

On the first day of the semester, we were given the task to write our own script entry for a 2000AD competition. I did not expect the first thing I do for this class was to produce a story independently, with no prior sessions on how comic scripts work or how to write a comic story. Upon learning about the project, my classmates started to discuss on their ideas right away while I was still worrying about how to make a story. Taking the direction of science fiction, I began to look for inspiration…

Back in December, I went to Denmark and visited a science fiction exhibition in the Brandts, an art museum in Odense. The exhibition content was richer than I thought, ranging from the themes of dinosaur, earth’s core, under the sea, space, Egypt myth, alien, cyborg, superhero, utopia/dystopia, etc. It showcased re-imagined props, models, landscape designs, books, and movie clips. I found them intriguing and useful for brainstorming and visualizing some early ideas for the comic. The exhibition showed how much potential the science fiction genre can offer to widen the scope of storytelling. I really like the idea of robots are evolving and blending in our lives. It makes me question the difference between humans and machines. I decided to include robotic characters that disguise as humans in the story.

Picture from The Painted Skin (2008).

Picture of K/DA Ahri from League of Legends by Riot Games.

I had the idea of modernizing a Chinese folktale, The Painted Skin, as a monster disguises herself as a beautiful woman to lure men and rip their hearts out as her meals to maintain her façade. Similarly, Ahri, a character from my favourite game League of Legends, is a nine-tailed fox from the Asian folklore who also has to absorb human essence in order to stay in her mortal form. In the game’s alternate universe, Ahri is part of a virtual music group “K/DA” made by Riot Games to promote a set of in-game skins. I was hoping to create an intergalactic band like the “K/DA” that travels across the planets to perform, but they are actually robots that have been sucking out the happiness from their audience to become more like humans.

Whenever they perform live, their music would absorb the enthusiasm from the crowd, leaving them depressed and lifeless. However, their music is not strong enough to manipulate strong and deep emotions. As a literature student, I believe that only humans are capable of writing literary pieces that can truly move the others. Therefore, I introduced a poet as the main protagonist who goes around with his poems. One day, a band member took the poet’s collection and decided to turn his poem into a song. In the end, when the band performed it, the song was so genuine and powerful that it drove the audience crazy and killing themselves. This would grant the robots so much “human energy”.

In mid-February, Monty dropped by the studio to give the class some advice on the project. I showed him the synopsis and he pointed out that the protagonist does not really have a motive. He suggested me to write more about the poet and his active investigation into the band. He explained this would allow the readers to attach and follow the poet around to participate in the discovery of the truth together. By the time the secret is revealed, it will have a bigger impact.

However, I could not think of any legitimate reason for a poet to wander around the band to do investigation. And I do not have any poetic verse on my mind to put into the lyrics to show how “powerful” these poems are. Therefore, I realized this character is not suitable for my comic anymore. I changed his character to a detective which I believe it has a more reasonable motive to get suspicious over the band and can carry out some form of investigation.

I amended the synopsis to the following:

“Following a detective who connects the mystery of increasing depression rate to the intergalactic music band Soulstealers, he investigates before the band is going to perform on his planet. During his talk with the band members, he leaves his poetry collection to them as they are interested in it. After a surreal experience at the concert, he is diagnosed with depression as well.

“At the clinic, he is told an ancient folktale of the Painted Skin, where a monstrous creature had to consume human hearts to maintain its disguise as a beautiful woman. He becomes determined that the band is going to threaten the galaxy with their music, but no one believes in him.

“The band releases a new song in the final planet of their tour which results in a mass suicide of the audience. The members are impressed with the effect of the new song as they acknowledged the poetry collection as their inspiration to produce music that can suck out the most human emotions possible. Unzipping their skins in the backstage, they reveal themselves as robots, who are trying to become humans.”

As my plot was becoming a sound story, I began to work on the scriptwriting and drawing thumbnails. I honestly had no idea on how to start writing a script and what a thumbnail is. All I knew about script is the Courier font. I felt helpless – there was no workshops or lessons on planning out a story or putting pen to paper. In a desperate move, I decided I would try to learn them by myself. I went to the library to look for books on writing comic scripts. I found a book by Peter David called Writing for Comics & Graphic Novels which I thought would be perfect to helping me out!

In the book, I have learned about the Marvel style and the full script style. I have learnt that the speech balloons are mostly kept “anchored” (148). When naming the characters, the book suggests linking up words associated to the characters, to find some cultural references related to these traits and to create some social scenarios to build up their personalities (on how they would react). I named the two of the band members Maria and HALi, which are references to Maria the robot from Metropolis (1927) and the HAL the computer from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Following the guidelines, I wrote the first page for my comic and doodled some thumbnails alongside with dialogues, so I could pair them with the right amount of words in each panel:

In mid-March, the class had a meeting at the studio where we got the chance to let our instructor, Phil, to check on our works. Besides approving my story, Phil commented that the formatting of my script was not very common as I named each panel by alphabetical order like the book did. Therefore, I updated the script in the correct format and started to draw the thumbnails properly. With the rundown of the story in mind, I drew the thumbnails, then updated my script on top of that. In this way, I could make sure each panel can include the right amount of information.

When visualizing the idea, I took inspiration from a newly-released Netflix sci-fi anthology – Love, Death + Robots. In one of the episodes, Good Hunting, it involves a nine-tailed fox/ “huli jing” (wicked fox lady in Chinese). The setting is in a steampunk colonial Hong Kong, which is my hometown. In the end, the fox lady infused her ancient magic with modern technology and became a robotic nine-tailed fox to hunt men. This is a perfect source for my story as it also references to the fox folktale and having charming performers revealing themselves as robots. I just thought the episode is stunning and amazing and see so much potential in my story as well.

Picture from Good Hunting in Love, Death + Robots (2019).

My classmate, Thanos, told me he would scan his hand-drawn thumbnails and edit them on Photoshop. I do not know how to edit drawn images on Photoshop. Therefore, I used the Comic Life 3 software that my professor has recommended me, to make my own framing for the panels. I printed the frames out, and drew on top of it by hand, then scanned them in again to become my final thumbnails. I have also shown my thumbnails to the MDes students, to see if they could understand my instruction through an artist’s perspective. Tony gave me some suggestions on the speech balloon placements and reading orders.

After updating the script, I have sent my work to my fellow MLitt students in the course, so we could cross-check each other’s work and exchange feedback. One of the advices from Thanos was to add a defining font for the band in the comic so to act as a branding and leaving visual hints of their robotic natures. Story-wise, they told me to add more clues, foreshadowing and explanation that the band has to consume human emotions gathered from their live performances. In terms of writing, Holly suggested me to proofread on my grammar as I sometimes describe the scene with present tense but sometimes with past tense.

After receiving feedback from my classmates, I moved on to finalizing my script. I ran through my work to Cam Kennedy when he dropped by the studio. I was so glad and relieved when he said that my story was well-presented. Encouraged by his words, I referenced the formats of my classmates and did one last amendment to the script and added the synopsis in the cover.

Looking back on the project, I am quite satisfied with what I wrote, given that this is my first time writing a comic script. When writing for each panel, I just knew how much contents to include. I realized that this could be a difficult step as my fellow classmate Holly had to cut down some exposition. I think this might be something that I am good at and should focus on improving this skill as my strength. On the other hand, character design, formatting and grammar are something that I should pay more attention to. I am grateful for Monty’s advice about the character’s motive and Holly’s help on proofreading the grammar of my writing. I wish I could have spent more time researching for comic scripts in the archive so to catch up with the script formats.

The second project in the module began as we were invited to the V&A Dundee during the second week of the semester. The class visited the V&A exhibition together and I felt like we were on a field trip which was very fun. Until we were told to make our own webcomic for the V&A website, in which they did not provide any “MLitt exception” like the scriptwriting option for the 2000AD project. I was devastated and felt helpless once again. I suggested to write an article by interviewing my class when they are producing their webcomics. Chris then suggested: “how about you make a comic on making the comics!” Phil also suggested that I can incorporate real life photos with the comics by visual editing tools. I began to ask my MDes classmates if they would be willing to help me to do some extra drawings and interviews.

A week later, the V&A Dundee staff came to listen to our ideas. My idea was to interview my classmates on making their webcomics at different stages of the project. When I told them my plan, it sounded very vague because I did not have any visual support to visualize the comic. Phil told me about a software called Comic Life which provides templates and visual aids for making a comic. The V&A staff reminded me to make the contents accessible to everyone – by explaining the context of the project and using easier phrases instead of comic jargons. After that, I tried out the programme and made the decision of making four issues of comics consisting of four panels each.

In order to give a sense of what it would look like, I mocked up two issues for the presentation. I edited my personal photos and placed them on some photos I have taken at the V&A and the DJCAD studio as the background. I wanted the photos to look like they were “drawn” so I processed them with different filters. Here are some slides I have presented:

After getting the approval and some advice for the presentation, I began to have small talks with my classmates and checking on them in the studio. I tried to take notes of who has material that is suitable for each of the issues, hence allocating them in different issues and reaching out to ask them for one piece of cartoon-style portrait of themselves. I was a bit worried if they would reject me since this means taking some of their extra time to draw and interview for me. Luckily, they were all on board and excited to see the idea comes to life.

I dropped by the studio for a week after the class is done with the 2000AD project so I could interview my classmates and took photos of their working areas. One of the difficulties for me was paraphrasing my classmates’ answers as I did not want to fill the whole panel with words without stripping away the gist of their words. I was worried about not following the unspoken rule of keeping each bubble under 25 words. However, I realized that the nature of this comic is more like a comic essay, so it makes sense to have more words.

The rest of my work was rather simple: I just had to wait for my classmates to submit their drawings to me, process their works and edited them to match the composition of each panel. I decided to unify the colour format of the comic to orange and blue which was inspired by the V&A Dundee website’s colour scheme.

When the V&A staff came by the studio for a final checking, they told me to amend the branding by using the full title of “V&A Dundee.” Phil asked me to adjust the speech bubbles so the words would not get so close to the edges. I tried to change the shape of the bubbles from circles to squares and changed the font from “Antihero Intl BB” to “Digital Strip.” By doing so, the gaps in the bubbles were widen while not covering up too much space of the overall panels. However, during the final presentation, Phil reminded me that this issue was still very visible and told me to use Photoshop to edit the lettering properly. Rayne kindly took me to the library and showed me how to do the work as I worried that it would “squeeze” the words as I resize them. Apparently, if I hold “shift,” I could adjust the size of the words in proportion which was a very helpful tip!

While working on this project, I really tried to capture all the important bits of the process and show the readers what it is like to make a comic. I wanted to do justice for all my classmates who helped me – to let them show their efforts and brilliant ideas behind each panel and to keep my webcomic as a record for the class to remember. Collaborating with the V&A Dundee was a really big deal and would look great on my resume so I wanted to give all I can offer to this project. There were many first-times in this project and seeing my comic coming together as a whole really surprised me for how far I have come. I have learned the spirit of “never say no” and be brave to give everything a try – luckily, my classmates were kind and patient to teach me through my mistakes and instructors gave me some helpful advice along the way.

The third project is the logo design which marks my first time of using Illustrator. I did not plan to make my own brand, so I did not have anything on my mind for a logo. The only thing I had been working on for this module was the blog so I decided to make a logo for the blog – Man Man Loi. It is a Romanized English for the Cantonese words 漫慢來 with the literal meaning for each word being “comic,” “slow,” and “come” respectively. I named my blog this way to symbolize my journey through this module – taking small steps in learning new skills and progress as a comic student. The phrase can mean “take it slow” in English. I believe in the attitude of “patient work makes a fine product” which comes from a Chinese idiom. If I ever take this brand to my work in the future, I would like it to represent my attitude in working as an editor with this belief.

Since the phrase is related to “taking steps,” I wanted to use stairs as the shape of the logo which symbolizes stepping upwards to the goal. Since reading English text is from top left towards the right hand side, the original line up of the words would read in a descending manner which did not match the concept of stepping up. Therefore, I changed the starting point of the words from the bottom left. There were also scrapped designs of a stick figure walking up the stairs or the dot of the “i” bouncing upwards. However, they looked ridiculous with my ammeter Illustrator skills and did not really help to signal the motion of going upwards. Therefore, I decided to keep it simple and only showed the English and Chinese words on a pink staircase. For the Chinese words, I struggled between placing the words on the stairs or on one side vertically so I asked my friends and they all prefer the latter one.

All in all, I cannot believe that I have made it through this module. Every task was a new challenge that sounded so impossible for me in the first place. Everything was very over-whelming for me and I had a tough time adapting to them. I remember something Phil told the MLitt students in the beginning: “Don’t let your limitation limits you.” These words pushed me forward to accept these challenges and I have come to realize that my limitations opened new ideas for me as well. For example, if it was not for the “no MLitt exception” in the V&A Dundee project, I would not have thought of making a comic about making comics! These experiences encouraged me to try new things and not be afraid to ask for help. I kept asking my classmates along the way and they were all very nice: doing an extra drawing for me, spending time to do an interview, teaching me on how to use different programs, reviewing my works etc. I have realized that my classmates are my biggest assets and I am forever grateful for that.

0 notes

Text

Thinks: Morehshin Allahyari

Active Sorrow: Interview with Morehshin Allahyari

Keeley Haftner: You’re still okay with me recording you for the Bad at Sports blog, right?

Morehshin Allahyari: Yes, I will tell you all my secrets!

KH: Okay, you are on record now. I have to admit to you that I’ve never done this before – you’re like, my test subject.

MA: Okay!

KH: So let’s start way back. You came to be known in Iran for a book that you wrote when you were twelve, translated in English as “My Ancestor’s Barefootness.”

MA: Yes, I was thinking about “barefootness’ not in reference to poverty, but in regard to struggles and taboos and things that my family had to deal with. It is a three hundred and eight page book. It’s about my grandmother, and her life in Kurdistan.

KH: What was the transition like to move to the United States in 2007 after being known in Iran from such a young age – to then be here where no one knew you in the same way?

MA: No one has ever asked me that! It was weird. In a way it felt like starting from zero. Not only do you move to a place where no one knows you or your work, but also, even if they did, they can’t read your book because it’s in Farsi. So not only was I immigrating independently to a foreign country, but it was also a personal identity crisis. It took me a long time to build something completely new from scratch afterward. I was not in a writing program. I was in a visual arts program and my bachelor was in theory and social science. The way I entered the creative world was through creative writing, so in my Master of Arts I was seeing the world as something very new, which was uncomfortable and weird. But perhaps it was a good moment. An opportunity to change things.

KH: Recently, there has been a surge to get deserving and underrepresented women on Wikipedia, which is so necessary. I noted that you have your own Wikipedia page! Thoughts?

MA: It just happened last year. An event to get women on Wikipedia was happening, so I thought to look myself up and there it was! It was pretty amazing. And it’s crazy because there are certain things that are not easy to find out about me that they were able to find and write about. I was like, ‘that is amazing, how did this happen?’

KH: Let’s start by speaking about your practice more broadly. Over the years your work has dealt with the intersection of Iran, America, censorship and capitalism, and the muddy places these complex subjects intersect. What might you say have been the most enduring questions of your overall practice?

MA: The core of my practice has always been related to political issues in the bigger picture, but also my own personal identity more specifically. For me, living in Iran was about censorship, and about learning how to use self-censorship as a survival tactic. Then, three years after having moved to the US, I decided not to go back to Iran. At that point I began making work that was political, and started putting it out in the world through interviews and exhibitions. So one thing I talk about often as my practice has developed is that there is a relationship between self-censorship and self-exile. Meaning, the less I censored myself the more I exiled myself. So a lot of my early work was about that. Later, I wanted to make work that wasn’t solely about my experiences with Iran, so I began to make work about the coming together of the two cultures. As with any immigrant, I am split between these two experiences and cultures constantly. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg of our experience. So even though this intersection became more of my work in some ways, I’ve always been really interested in technologies, and how they can be used to make critical, political, and social work. Perhaps the real subject of all of my work has been archive and documentation, and how we negotiate the different platforms we use doing so. I am interested in how technological tools – a web or net art piece, experimental animation, 3D printing – can be used as a way to archive or document a certain kind of life. I’ve always tried to maintain this as a constant I can refer back to.

KH: When did your relationship to the digital begin?

MA: My Master of Fine Arts at the University of Denver and then M.F.A. in New Media Art at University of North Texas was where I learned about experimental animation, and 3D modelling and animating in Maya, which I fell in love with because I felt that suddenly there was this virtual, imaginative space that I could build from scratch.

Morehshin Allahyari, Remembrance of time; Origin of forgetting (2013)

KH: Speaking to worldbuilding, I’m interested in how that gets done for you IRL. We met through your collaborative project with Daniel Rourke, beginning with the on the 3D Additivist Cookbook and progressing toward our exhibition at Schering Stiftung for Transmediale, On the Far Side of the Marchlands. Could you talk more about your relationship to collaboration, both as an artist and curator?

MA: I have always done collaborative work. I believe it’s the very first step toward community building. Working together organically with people from different backgrounds and experiences produces a sort of magic that won’t happen when you’re working individually in your studio. Back in 2010 I curated and organized a collaboration between myself and other artists in Iran and the US called IRUS, for example, where for a year we collaborated back and forth. So I’ve always been interested in collaboration as a sharing space that evolves through time and trust. With Daniel it was the same. He did an interview with me three years ago for Rhizome where we discussed my use of 3D printing and art practice, and afterward in Chicago we talked briefly about how we should make a cookbook. We decided before doing the cookbook we should do a manifesto to position ourselves, and so it has all come together very organically without forcing it. And it’s been wonderful – a really amazing collaboration. We both have had so much influence on each other’s practices as we’ve grown as artists and writers.

Allahyari, Moreshin & Rourke, Daniel (ed.), The 3D Additivist Cookbook, Amsterdam, NL: The Institute of Network Cultures, 2016

KH: You have a lot of work up right now: Solid State Mythologies at the University Gallery at UMASS Lowell, and Material Girls at the College Galleries in SK, Canada, and which funny enough I chanced upon when I was back home. I thought it was interesting that both exhibitions had your older work, Like Pearls, from 2014 in them. How does that particular work relate to the Dark Matter series you are continuing to develop at Eyebeam’s Research Residency in New York?

MA: Both are about feminism, female powers and female bodies, but Like Pearls specifically is about censorship and the female body, as well as the global web aesthetic that has been localized in a culture like Iran’s. The material was gathered from spam that I would get in my Yahoo email account about online lingerie underwear stores that were mostly marketing toward men. They advertised in a way that was supposed to be about romance or love – “buy this for your wife” or “the one that is yours forever” – because they’re not supposed to say ‘lover’ or ‘this person you want to sleep with’. The love being marketed in these ads was also an aggressive love, in some ways. Like, “tell her to wear the underwear that you find the most sexy,” which is why I’m using Backstreet Boys audio (They were really popular in Iran when I was a teenager), and when you actually listen to their lyrics they also have this very aggressive love thing going on.

You are, my fire The one, desire Believe, when I say I want it that way

So I was really interested in bringing all of these elements together, but specifically I was amazed by this surreal aesthetic. You see these women and they are wearing this sexy lingerie, being advertised and objectified, but all their bodies are censored. It’s such a weird concept. When you think about sexual censorship, you usually think about a black bar, but it was not like that. There were colours and patterns, some white and some erased so you could only see uncontroversial body parts, like an arm. All of these small very detailed choices in advertising became really fascinating to me. So I made web-based work with the material, heart GIFs, and translated the aggressive love quotations and made them pop up if you clicked on them. So that was that – it was about this relationship with the female body: censorship, ownership, and web culture. How the aesthetic of the web changes in different cultures or remains the same.

Morehshin Allahyari, Like Pearls (2014)

But in my new body of work ‘She Who Sees The Unknown’, it’s actually about female figures taking over some kind of power. During my residency at Eyebeam, I’m talking about how tools like 3D scanners and 3D printers have become tools of digital colonialism for a lot of Western archaeologists and companies based in Silicon Valley. People will go to the Middle East and scan a cultural site or artefact, and then claim ownership of the data. A lot of them make money off the files, and then only give access to specific institutions they can profit from. That’s digital colonialism – a way to take over our ‘shared’ universal heritage, whatever that is. So I’m re-appropriating them. I use the same technologies these companies use to work against this trend, by 3D printing dark female goddesses, these monstrous figures and genies. A lot of them are genies (Jinns). Each of them will take over some sort of power, based on what they did in their different myths, histories, and narratives. Each power will be related to something contemporary. First there’s the research, then I am writing a text to accompany each figure, which will be a mix between fact and fiction – like a narrative. Right now there is one: HUMA, who is known for bringing fever and heat. But soon there will be an army of them.

Morehshin Allahyari, She Who Sees the Unknown (2017)

One thing I’ve been really interested in is this idea of re-figuring – how re-figuring and re-imagining the future can become an activist-feminist practice. I think it’s such an important time to talk about alteration, given everything that’s happening. I was just having breakfast with an Iranian friend of mind who has a work visa, not a green card, and he can’t leave the country. He just can’t risk it. So now he’s basically in jail. In March, he was going to go to Iran – he just cancelled that. We had such an intense conversation about our bodies being attacked and pushed out, being rejected. We talked a lot about rejection. For me this all relates to a need to re-figure and re-imagine – a need to bring these female powers and bodies back into existence, and then doing something else with them. But also with all of the recent events that have happened, I think it’s definitely going to influence where this research is going.

KH: It seems important and timely that the archive you’re working on and building is not only in part a retelling of unspoken histories outside of the mainstream of Western culture, but also a reformulation of them for a contemporary context, in ways that tell new stories about women.

MA: Yes, it’s that, but we could also talk about the Western imperialistic and colonial side of it. Dark Matter is about a kind of feminist practice that exists for women of colour. For example, feeling the problematic urge in the Women’s March for universal feminism. There’s no such a thing as universal feminism. And there should never be, because we need to talk about worlds, about singularities, and about different concerns I might have that a white feminist wouldn’t. I am bringing dark goddesses and djinn figures based in the Middle East to the US at the same time Middle Eastern brown bodies are being pushed out. We don’t talk specifically enough about brown bodies in mainstream media. So for me it’s about that, but it’s also about doing a kind of witchcraft: doing magical performances with the 3D scanner in a world of talismans and spells and magic, which is also super white feminist right now. It’s very trendy, and I want to interrupt that.

KH: What are the differences between showing your work in Middle Eastern and Western contexts? I think about the white gaze consuming these works, but also what it’s like to produce work for an exhibition in the United States verses Iran and how your language might change or stay the same.

MA: That’s a really good question. I’ve never made site-specific work, except for writing I suppose, because I have to write in certain languages which presupposes certain knowledge. If an Iranian or Middle Eastern person walks through a lot of my work, they can understand so many layers without having to read a statement. A non-Middle Eastern person wouldn’t be able to do that. So this is something that I think about a lot. Like what does it mean to produce certain things that people from this culture or other countries might not understand, or that they have to do research to understand? They have to read about things. And especially this new body of work that I’m doing – it’s very research based. I’m gathering tons and tons of material, a lot of which is in Farsi and in Arabic. These are very old materials that are not translated. In my current exhibition at TRANSFER Gallery in New York where I showed the first figure from this new body of work, I had these three spells on the wall that I scanned from this book and it was in both Farsi and Arabic and I didn’t translate them. So if someone who knew Arabic walked in they would be able to read it, and it would change part of their experience. But as a Westerner you had to actually read all the material that was in this archive to be able to understand, so you had to work harder – much harder – to get to the same knowledge. And part of me is really okay with that. Like making my Western audience have to try to get knowledge that usually they don’t try understand or get. I was just bitching about this yesterday on Twitter…

…about how tired I am of constantly having to adjust myself to Western cultural knowledge, political knowledge, geographical knowledge. These days I only want to hang out with people who actually want to learn about mine and other cultures. Western knowledge is so dominant. In order to get access to things you have to know all this stuff about American history, or about the West. Americans don’t feel the same responsibility toward other countries. This is such an important time to reverse this. People should feel responsible to reverse this, in a way. So that’s what I want of a Western audience. I want them to do their research, to work hard, and to learn things on their own – without going around and asking an Iranian things like, “so does it snow in Iran?” you know? It goes both ways. I might show a work of mine in Iran and people don’t understand nuances about it that someone in the West would understand very well. So it’s kind of split. The same as my life is, the same as everything is, existing between these two worlds.

KH: It strikes me that your earlier mention of “universal culture” might have fruitful complexity: the idea that one must fight against the assumption that there should be a universal culture, while at the same time work hard to understand one another, which perhaps could inadvertently promote a universalizing in some way. It makes me think your piece, Dark Matter (Second Series), being commissioned by Forever Now to be gifted to NASA to be taken to the International Space Station. There you are taking things are that are culturally unwelcome in certain countries and literally putting them making them universal – as in, out in the universe.

MA: The Second Series includes objects and materials that are taboos in Iran, Saudi Arabia, China, and North Korea. I like the idea that once these things leave our planet, this world where a minority has made certain things taboo and forbidden for a majority, then they are no longer taboos. They no longer need to be censored. You just put these things in outer space where they’re away from all human bullshit and they’ll be fine there. I think it also relates to the way we speak about the web and digital archives as spaces beyond these more guarded or even ignorant forms of preserving and sharing knowledge. They become a universal space, or at least they operate that way in a utopic sense.

Dark Matter (Second Series 2014-2015)

KH: But of course with the Manifesto that you and Daniel created I think there’s also an edge of dystopia, which I think maybe relates to the way the complexity of optimism and activism.

MA: I’m interested in both utopia and dystopia. A lot of my work has this very dark black and white aesthetic, and the text from manifesto is more dystopian than utopian. The dark goddesses and female monster figures are both cruel and ugly. But I think that there is a way dystopia can be optimistic; you know what I mean? It’s about embracing the darkness. You embrace dystopia so that you can turn it against itself. You still take action. I also very much believe in micro-actions. Without changing the world or solving immediate problems, small actions and influences can make bigger changes. Something I’ve been thinking about the last two or three years is how to make a work that is about sorrow. Sorrow is very much embraced in Persian culture, poetry, literature, and all of our songs. And I think people there in a way are happier and healthier mentally. Here in the West, happiness is the goal. Americans always say “if it makes you happy”, which is rarely said in Iran. It’s so weird to think about language and how we interact with each other. I’m interested in sorrow as a transitional state. And the same thing goes for dystopia – if you embrace dystopia and you can talk about these dark figures and this monstrous other female forms, the result will be a better, more positive, and critical space. I’m not interested in the techno utopian technologies that many activists are – it’s all very general. Peace and love as an activist strategy are played out. I’m interested in activism that comes from a different place. It’s not a violent or harmful activism. It’s dark and dystopian, inclusive and generous. You can be a nihilist and be hopeful. They’re not oppositional. So perhaps that’s what one of these female goddess figures could do: be sorrowful and embrace the sorrow.

KH: Anything we didn’t cover?

MA: Thank you – this was such a nice conversation. I am so tired of the same questions over and over and this was very refreshing. Maybe the last thing I’d like to mention is around privilege and responsibility. Myself and so many of my Iranian friends – we’re all in a privileged position obviously because we’re the educated ones, we’re the ones who got to leave Iran and come and get scholarships and study here. Not rich kids, but privileged. So we try to understand our position, but especially in the last two or three weeks and since Trump and Brexit, I’ve been finding it really hard to sit on panels that are about machines, Artificial Intelligence, and the Western prediction of the future, where we’re being asked to try and understand what this future means and how it relates to technology, how it’s going to change, etc. So much of the world is on conflict and in such a weird place, so it’s very hard for me to sit through these kinds of privileged, Western discussions. So I guess what I’m trying to say is that something has changed dramatically, in a strange way in so many of our lives, and the lives of specifically Middle Easterners, and I’m still trying to understand how to deal with that. Obviously, I still want to be sympathetic to other people, both their problems and their concerns, but at the same time I sit through these things and I feel so alienated by them in a way that I haven’t before. Yesterday I was in a panel and told people that I wish we could reimagine this future in a way that we’re really uncomfortable with it, maybe? Because I don’t also want to live in the future of Elon Musk, the one white men have predicted for us. But then the conversation just went immediately back to all these mostly white mostly American people talking about their security and privacy with Facebook. And I was like, I can’t do this. I cannot sit through this. It felt like the whole world being hungry and people sitting around talking about organic food. So I just wanted to say that there is a need to reimagine and alter things, as well as a need for people who are not from these countries to take responsibility without asking us how to do it. I think that’s a very important moment for that, and for the very first time I actually feel okay to lean that way. So don’t put the burden of the conversation on us. Anyway, I hope we can do that. I hope people can start to think of all these relationships more, and that things change for the better, if that’s still possible.

Morehshin Allahyari is an artist, activist, educator, and occasional curator. You can find her complete bio here.

Endless Opportunities (Or Something)

Eyewitness Account of Barney/Peyton Collaboration “Blood of Two”

The Public is the Teacher: An interview with Justin Cabrillos

A New Samarkand: Regionalism in the Age of Globalization

Episode 372: Catherine Sullivan

from Bad at Sports http://ift.tt/2mFiM07 via IFTTT

0 notes