#this is also the first disney film i've watched since Encanto and the second I've watched since idk ...

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Missed Potential of WISH

It’s funny.

Last year, I really wanted to watch the new Wish animated film from Disney.

While everyone else were hating on the art and animation style, I actually kind of liked it and was genuinely looking forward to possibly viewing it on the big screen.

Then the reviews came in. Needless to say, I didn’t watch Wish.

I remember a time when people used to complain about Disney making “too many love stories”. Then Disney stopped making love stories leading to films like Moana, Coco, Encanto and even Turning Red, which weren't bad.

Following the failure of Wish, the biggest complaint I’ve heard for that film is that “it probably would’ve been more successful if it were a love story”.

The last romance Disney had we’re the protagonist was a “black girl” was Tiana from The Princess and the Frog which was technically their last 2D animated feature film.

And don’t get me wrong, til this day, The Princess and the Frog still tracks. Second to Tangled, I still very much love TPATF and it's one of Disney's classics that definitely have the rewatchability.

That being said, Wish is the first Disney film I've seen where the missed potential of what its story was originally supposed to be (herego a love story between a human girl and shape-shifting star boy) versus what we actually got is more popular.

Aww Disney, what were you thinking?! How could you think a film where the main character, who is a PoC, the first "black girl" (well technically I think Asha is meant to be mixed) female lead/love interest that you've had since Tiana in The Princess and the Frog in 14 YEARS where she is actually human for all of the movie and gets to share a love story with a handsome "star boy" who can literally make all of her dreams come and think that that's NOT gonna make you money!

I haven't even watched Wish yet I've seen more artwork and fan-made animatics of Asha and Star Boy than anything from the actual film.

At this point, Disney should just take all of the original ideas they left on the chopping block for Wish and revise them into a future title which is an actual love story they could market from.

Or…as an audience, we can just wait for one of their competitors, like Dreamworks to smell the blood in the water like the sharks they are and capitalize on Disney’s latest flop by taking the ideas they didn’t use and coming up with something that could potentially usurp the popularity of Wish’s failure.

In the case of Dreamworks, they don’t even need to make a new star boy since, technically, they already have potential “star boy” they can use.

Remember Rise of the Guardians?

Hahaaaaa OF COURSE you do, since it gave us the original immortal boy internet heart throb (also ironically voiced by Chris Pine who played King Magnifico in Wish) ---Jack Frost.

I find it hilarious that another reason why folks are hating on Wish so much is because Disney could've given us another potential immortal boy heart throb "Star Boy" to finally usurp the chokehold that Jack Frost has had on our generation of weebs and artists for the past 12 years since RoTG first dropped.

We could've had it all.

But as I mentioned Rise of the Guardians, did you know that there is character in the original series it was based off of called Nightlight?

While technically not a “star boy”, Nightlight is the closest thing to one in an already established universe from a Dreamworks property and since this squiggle meister never misses a beat to push for continuation of Rise of Guardians, hear me out:

Imagine a Rise of the Guardian prequel-sequel about the character Nightlight and make it a love story.

(Because apparently there's a girl that Nightlight grows close to in his story called Katherine. It's just a friendship but needless to say, there is potential there).

I know it’s been 12 years since Rise of Guardians first dropped and I know I've be hollering for a sequel since 2012.

But c'mon, if there was ever a time for Dreamworks to capitalize on an RoTG sequel, it's now.

As Wish has proven, the internet is hungry for another handsome immortal boy with magical powers.

Dreamworks set the ball rolling with Jack Frost.

If Dreamworks were to revisit RoTG again, take Nightlight's story. Take his design and give him the "Jack Frost" treatment and make it a love story on top of that.

I'm not saying it will happen. Not even saying it could happen.

But if somehow thought becomes reality and something like this does actually happen, whoever does it will be rolling in dough.

This is just a longwinded way of me to say that somebody needs to bank on the concept of a star falling in love with a human and do it now since as the internet has shown, it's what the people want and what Wish failed to give.

~LMS (2024)

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

just a random thought

Anybody ever check out this youtube account called The Take? I only pass it once a blue moon. I did like their video on Cinderella. But a couple of weeks ago I noticed this video

youtube

Now I'm not gonna go into a lot of detail/or rant for two reasons. One, I'm not black. Or a minority... I think (look not getting into that can of worms). But I did sit down and listen to it because at thumbnail glance I didn't know what they meant.

But then after I listen to it... I sat down and saw of couple examples that made me think "Omg they're sooo right". And... its still a thing? " even after this video was made. Again not gonna get to detail. I'm just having an "aha" moment cause I've been watching TV.

Lets see comic wise, (and this will probably offend a Wandavision fan, no you're not welcome8B). Comic wise, Wanda aka Scarlet Witch had finally dumped Vision and I was okay with that. Comic wise he was a bore. Maybe he was fun in old years but now he's boring.

Secondly, I thought Wanda could do better. And they gave her Jericho Drumm aka Doctor/or Brother Voodoo. And I thought at first glance "Oh he's got a great design". And I don't know a lot about him. Maybe we'll get more story. Nope. Wandavision came out, Marvel suddenly forgot she had a good thing going. Now everywhere I turn its Vision, its Vision. He can't/or won't leave her alone. Even though he's made/or had two different relationships and kids which he ditched one pair.

I'm like "Why are focusing on him?". What happened to Jericho? Only analysis... Jericho's not selling. They literally scrapped him (even though they didn't finish/or get to explore it more) for Wandavision. Gah and ever since the MCU I hate Vision more cause he's a pointless trope. But anywayyyys back to another example.

Second/and third is TV examples. Second is an old entry but I'm gonna use it. Boy Meets World. Angela and Shawn were a GREAT couple and I do mean a great couple. Angela should had been the end game.

But at the end of the day the writers?/creator/or Disney?(dunno who to blame and don't care).... didn't value Angela and pushed her aside for the white chick.

Then there's an ABC show Will Trent. Season 2, I was very hopeful. Will Trent was flirting with a lovely black lady Cricket. And I thought "Oh good a HEALTHY relationship". Nope episode 1, they literally kill her off.

Whats the motivation? Only for the writers to push him back to Angie, the toxic white girlfriend. Besides that trope, I guess it also counts as fridging. Such a waste of actress.

And I'm just gonna point this out, not counting TV shows. Disney's guilty of this themselves. Now I don't entirely think they mean to do it on purpose. But just looking I'm noting this I'm looking at their FEATURE films. I think with all this whole "FEMINISM" means "we don't need a man/love story" into the movies.

Which at first I get. Now animated(2D) only three of the Disney princesses are of color with a relationship. (Sorry not counting Pocahontas thats a historical mess. Sorryyy) But since transitioning into CGI... none of the new princesses are getting a love interests. The ones of color. The white ones did aka Anna and Rapunzel. Even if we argue "Oh Elsa will get one" again she's still white. And no not counting Encanto either. Uhh cause the focus is usually Isabella and Luisa, they're single. Same for Maribel but she's a kid so not holding her to it. Do I count Dolores... pft sorry no. I blame the writers on that.

But none of the new princesses of color have gotten one. Not even Asha, Asha would have gotten one originally but they scrapped it.

Now again before someone jumps me. I don't think they mean to do it on purpose.

0 notes

Text

"Encanto" and the myth of the Magical Latin America

Well hello again my gorgeous maritacas ✨ Today, we talk yet again about, yes, colonialism.

SOO, I hope I didn't miss the boat on this subject, cause I've been wanting to write about it since I first saw the very first divulgation of Disney's most recent animation movie, Encanto (2021).

I am Brazilian, born and raised in Latin America, and I have been in love with this place since I opened my little dark brown eyes. I spent most of my academic years researching latinex art and culture and history, and one of my deepest passions is our literature. So imagine my instigation when I heard Disney would be making this movie.

You see, in addition to taking place in Latin America and in a country neighboring mine, which would already be a reason for me to be 1000% more intrigued about this, most of the comments and publicity over it followed this line:

✨Magical Realism ✨

And then I started to worry

And then I watched the movie

Then I got more worry

Because, yes, I know that this is an ongoing discussion on if Encanto is Magical Realism or not, and there're people debating very fairly on both sides, but here I'd like to leave my arguments over why and how I feel culturally obliged to disagree. So, this is my point, and my side, so please don't take anything I say here for fact or go on me for idk, indoctrinate in an argument. But I will be linking a lot of references for you to really see where I'm coming from here, and that place is

NO, ENCANTO IS NOT MAGICAL REALISM

And we really need to talk about it

So buckle up, because this will be long (but necessary, trust me)

SO, I went to read those interviews with the directors and producers of this movie and they said this:

" [...] once Charise joined us, she had such a great grounding and magical realism, that this place, Colombia, which is one of the cradles of that literary style with Gabriel Garcia Márquez, it just made total sense, talking about a family. And a great way to get organic Latin American magic into this film without trying to force it into some European type of magic, that you’ve maybe seen before in other films." (source)

And then, when asked about the differences between "European magic" and "Latin American magic", Charise Castro Smith said:

"Well, I think magical realism is a fast tradition that doesn’t just exist in Latin America. It’s a literature tradition that’s throughout the world. But I think the way we started to think about it and sort of define it within the context of our film, was that it was magic that was born out of emotion. Magic that was born out of character and relationship, instead of something that was like an external force sort of foisted upon the characters in the story." (x)

So, they defined Encanto as "Latin America magic", and defined it as Magical Realism, and that as "magic born out of emotion".

That is not wrong, but that's also not quite right. From what I could get from these interviews, the thing is that, maybe it was wrong phrasing, but I think they mistook Magical Realism for metaphors.

But before I get into that, I have to state that I really liked Encanto. It's fun, it's colorful, and I really think they've done a great job representing how Latino families are structured, and how we relate to our families. I could relate to a lot of the situations in the film on a very personal level, and one of the ways they were able to do that, in my opinion, was through the use of, yes, metaphors.

Because, in this movie, you can divide magic in about two ways:

First, when it's used narratively. That's the case of Bruno's magic, and Dolores', for example. And actually, kudos to Dolores for being one of the biggest narrative tools I've seen in a long time.

And second, when it's used as a metaphor. That would be the case of Luisa's magic, and Peppa's, and etc

See that? That's a metaphor. A very clear one.

And it works just fine. It's good. It's well done. It does a great job passing the point. Magic, here, works as an external representation of internal conflict. Makes us able to get the metaphor and relate to these very personal conflicts without directly addressing them (which would make the movie way, let's say, heavier to watch kkkkkk I'm so funny). So yes, I definitely agree with Castro Smith that Encanto is about magic that comes out of emotion. That's great, 10/10.

But that's not what Magical Realism is.

And I could get into why the whole "magic as metaphor" thing couldn't be considered "European magic" or what even is "European magic" anyway, which would lead me to this whole "let's talk about Christianity" thread, but I'll stick to my current point here (for now)

And for you to properly understand my point here, before getting properly into Encanto I'll have to do some contextualization first, so...

1. MAGICAL REALISM

Let's name the donkeys (Brazilian saying, sorry).

So, the thing Castro Smith said there above, about magical realism not being like, Latin America exclusive? That's absolutely right. We have a huge plurality of great works and authors writing Magical Realism all around the world (one of my favorites is the Mozambican writer Mia Couto, btw). So, for this little contextualization here, I'll quote some lines of another post I wrote about Magic Realism, applied specifically in the context of Brazil (and feel free to check it out here), but which sufficiently covers my point at the moment:

To make matters short, if you never heard of it, Magical Realism is a 20th century genre that portrays "a realistic view of the modern world while also adding magical elements" to it, without this "magic" being perceived as such within this established world.

Matthew Strecher (1999) defines it as:

"what happens when a highly detailed, realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe." (source)

So, basically, one of the key points of Magic Realism is the assimilation of this magic as not being "magical" — as we are used to understanding "magic", but rather an estrangement within an apparently common scenario. It is closer to the uncanny than to the fantastical, and the fact that the "commom" people (the characters) within these realistic and common settings do not seem to perceive or assimilate the uncanny as being uncanny, is what creates this feeling of enchantment in these works.

And yes, I know that technically Magical Realism was born in Germany in the 20s, but it really peaked in America Latina. When you think of Magical Realism, the names that probably come to mind are Frida Kahlo, Gabriel García Márquez, María Luisa Bombal, etc. etc. We just nailed it.

And Frida can't let me lie

In his Nobel-winning speech (called The Solitude of Latin America) for his book Cien Años de Soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude), the Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez addressed a somewhat poor understanding of his work on the part of European society, who might perceive our Magical Realism as being fanciful and enchanted.

He said:

"I dare to think that it is this outsized reality, and not just its literary expression, that has deserved the attention of the Swedish Academy of Letters. A reality not of paper, but one that lives within us and determines each instant of our countless daily deaths, and that nourishes a source of insatiable creativity, full of sorrow and beauty, of which this roving and nostalgic Colombian is but one cipher more, singled out by fortune. Poets and beggars, musicians and prophets, warriors and scoundrels, all creatures of that unbridled reality, we have had to ask but little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable. This, my friends, is the crux of our solitude.

And if these difficulties, whose essence we share, hinder us, it is understandable that the rational talents on this side of the world, exalted in the contemplation of their own cultures, should have found themselves without valid means to interpret us. It is only natural that they insist on measuring us with the yardstick that they use for themselves, forgetting that the ravages of life are not the same for all, and that the quest of our own identity is just as arduous and bloody for us as it was for them. The interpretation of our reality through patterns not our own, serves only to make us ever more unknown, ever less free, ever more solitary."

I've linked the full speech there above. It's translated to English, but I highly recommend you read the original in Spanish, if you can understand it. Is incomparable

What García Márquez is saying is that there is a subtle difference in the way we Latinos relate to Magical Realism. For us, the fantastic is not there because it is magical or beautiful, or simply as a metaphor. Yes, it is a metaphor, but one so ingrained in our sentiments and experiences that it becomes very difficult to explain or translate to outsiders. The fantastic is actually an European-imposed way of seeing ourselves, because it's how they saw us since the 1500s.

2. THE MAGICAL TERRA INCOGNITA

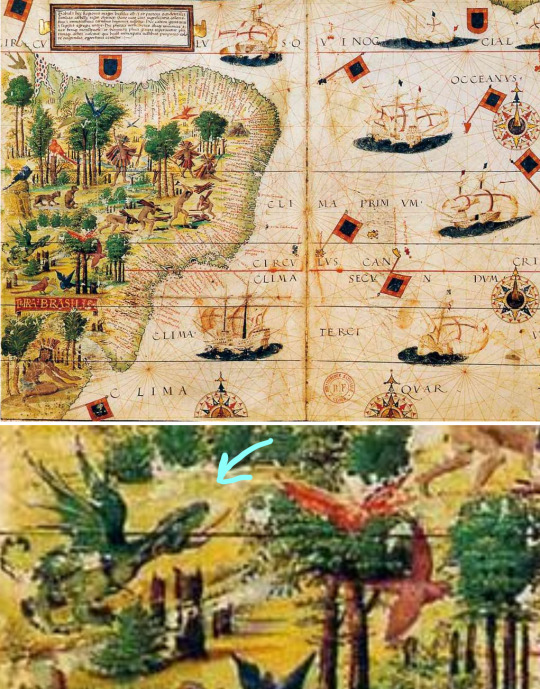

When Europeans first arrived in our lands, they described Latin America as a land of enchantments. As they were not familiar with the native cultures, native peoples, our fauna and our flora, their way of seeing us was through the lens of the fantastic; lens that they created themselves. If you search online, you will find a series of period maps of the South America depicting magical creatures:

Map by Pedro Reinel and Lopo Homem, named Terra Brasilis, 1519

See the little dragon? That's actually a true story: you see, when the Portuguese arrived, they heard the jaguars roaring in the woods, and thought it was the sound of dragons. They saw the manatees swimming under the river and thought they were mermaids.

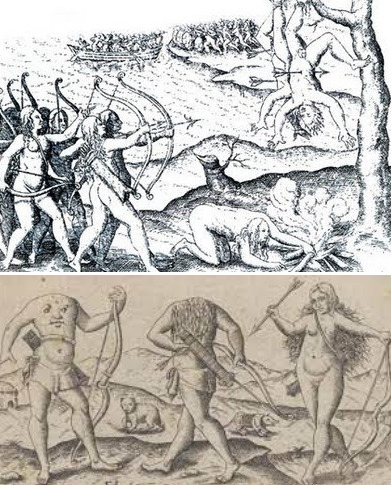

As they entered the Amazon River, some boats were attacked by the Icamiabas, warriors of a matriarchal indigenous people in which women went out to fight — and they were spectacular warriors. Seeing these women, the Europeans thought they had arrived on the magical island of the Amazons, of Greek culture. And that's why the Amazon River is now called "Amazon", and that's why the forest is called the "Amazon" forest (source). Because Europeans mystified native peoples.

And ultimately, fetishized and bestialized these native peoples.

And that's just like, 3 examples in the specific context of Brazilian colonization process. That's just the tip of the tip of the iceberg.

Regarding that map above, the professor André Reyes Novaes, in his article "Terra Brasilis as Terra Incognita", says (translated by me) that

"At that time, “Terra Brasilis”, as named on the map, was “Terrae Incognitae”, which gave cartographers “carte blanche” (free pass) to fill in the “empty spaces on the map” (Safier, 2009). El Dourado, Ilha Brasil, the Amazon Warriors and many other “myths” occupied the interior of the continent on maps in the period of expansion of the Iberian colonies. [...] Contrasting with the "mythological" interior, the sea appears full of caravels, coats of arms and flags, a space clearly determinated and scratched by the geometry of the orientation lines of the portolan charts. [...] According to Hiatt (2008), the expression terra incognita is today a powerful metaphor, because even in the era of the comprehensive “Google Earth”, it continues to be applied to discuss the relationship between imagination and “unknown” spaces by specific groups. As Wright (1947:72) stated, “if today there is no terra incognita in the absolute sense, there is also no absolute terra cognita”, as we continue to relate to space based on socially produced and shared representations and models." (source)

So, through these records, Europeans created the contrast between European civilizations (organized, mapped, civilized) and native civilizations (bestialized, savage, magical). And that was a very important tool in the domination of our lands. Because when you mystify a people, you dehumanize that people. And it is easier to dominate a dehumanized people.

This enchanted narrative they created actually masked a history of oppression, exploitation, rape and genocide.

And this fantastical way of seeing ourselves ended up being imprinted on us. Magical Realism does not exist to be magical, it exists to express in words, using the language that has been imposed on us, the absurdity of our narrative. It's the way we can translate the reality of our otherwise unbelievable history. As García Márquez said,

"we have had to ask but little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable".

And this resonates even today. Because even after the movements of Independance, Latin America suffered and still suffers from the consequences of colonization, first by Europe, and later by the United States. As Reyes Novaes continues:

"As literal terra incognita, the South American frontiers have gone centuries without being properly explored and represented by European cartographers. As metaphorical terra incognita, these regions continue to be recurrently qualified through imagination and shared narrative in metropolitan centers. Even in the 21st century, the idea of “empty space to be occupied” still populates the imagination about the borders of South American power centers and new mythological “monsters” are represented in these spaces, such as drug-dealers, invaders, smugglers and criminals." [...]

"Considering the metropolitan and coastal vision of many Brazilians, Terra Brasilis remains Terra Incógnita, a relatively "empty" and "uncivilized" space, dependent on public policies formulated from outside. The persistence of this vision in the 21st century is perhaps one of the great challenges for the recognition of our own dynamics and autonomous exchanges existing in border spaces, often imagined as areas to be occupied, protected and colonized by the metropolitan centers." (x)

And by no means this just the story of Latin America. This is the story of Polynesia. Of Southern Asia. Of the African Continent. Of so many nations genocidated by the violence of the colonizer. This mystifications (and later demonizations) of non-European cultures shaped the fantastic imagination of these cultures. That's why I said that Magical Realism found a huge plurality around the world. It represents the imaginary of a colonized nation.

3. MAGICAL REALISM AS A WAY OF PRESERVING AND EXPRESSING COLLECTIVE MEMORY

For this, I'll use García Marquez's work (so often cited to relate to Encanto) as a reference. In his best-known work, One Hundred Years of Solitude, García Marquez weaves the story of generations of the Buendía family, founders of the city of Macondo, over 100 years.

After the book's release, not few managed to find, in Macondo, an analogy for Latin America itself, and the events that surround the characters in the book, mirrors for events that marked our own history.

The metaphors that appear throughout the book, not so much metaphors for personal feelings, are closer to metaphors to express the feeling of an entire nation during actual events, as he said in his speech, of unbelievable, "unbridled reality".

Look at this excerpt:

"Although in the months that followed they reinforced the grave with walls about it, between which they threw compressed ash, sawdust, and quicklime, the cemetery still smelled of powder for many years after, until the engineers from the banana company covered the grave over with a shell of concrete." (source, p. 69)

At a certain point in the book, an American arrives in Macondo and, settling himself next to a train line, starts an innocent banana plantation. Later, his business grows and he starts a banana company, which takes over Macondo and suddenly, the entire production of the city consists only of bananas. Macondo no longer produces anything other than bananas, which are quickly loaded into huge train cars that carry these bananas away. The city is then taken over by a banana plague, and as the above passage describes, eventually even the cemetery is covered by the banana company.

Now, if you have ever studied anything from Latin America, you will probably immediately associate this with the famous United Fruit, a real multinational known throughout the world for creating the concept of the Banana Republic and for changing the political and economic directions of an entire continent (ours).

It's like a scheme:

Basically, using local (and inhumanly cheaper) labor, they specialize in the cultivation of a single commodity, produce that commodity on a large scale (thus ending any family farming systems that might exist and alienating production and the local market) and then export this commodity abroad at ABSURDLY lower prices than other markets. That's what happened with the banana. This type of system forces a country to remain in underdevelopment, and this was a large-scale project carried out in Latin America by the United States. And we reap the "rewards" of that in our industry and economy to this day.

And then García Marquez writes:

“Look at the mess we’ve got ourselves into,” Colonel Aureliano Buendía said at that time, “just because we invited a gringo to eat some bananas.” (p. 114)

Do you know what happens next? The exploited workers revolt against the banana company, and they are all machine-gunned by the American military. Women and children too. After managing to escape with his life and return home, José Buendía counted about three thousand dead. And when he goes and tells all this, horrified, to the first person he meets, do you know what that person says to him? She says "What are you talking about? There weren't any dead".

"The official version, repeated a thousand times and mangled out all over the country by every means of communication the government found at hand, was finally accepted: there were no dead, the satisfied workers had gone back to their families, and the banana company was suspending all activity until the rains stopped." (p. 151)

Now you go, and you Google "United Fruit Banana Massacre" or just "Banana Massacre". That's the Realism in Magical Realism.

Through a prosaic narrative, what García Marquez is doing is documenting historical events. Trough the narrative of One Hundred Years of Solitude, García Marquez told the story of his own land.

And the banana case is clearer to understand, but these historical relationships run through every aspect of the book. Take this other example: Right at the beginning, the narrative shows the patriarch of the Buendía family, José Arcadio Buendía (and his wife Úrsula Iguarán) guiding a group of people into the virgin forest in search of a place to build a village, and then,

"When they woke up, with the sun already high in the sky, they were speechless with fascination. Before them, surrounded by ferns and palm trees, white and powdery in the silent morning light, was an enormous Spanish galleon. Tilted slightly to the starboard, it had hanging from its intact masts the dirty rags of its sails in the midst of its rigging, which was adorned with orchids. The hull, covered with an armor of petrified barnacles and soft moss, was firmly fastened into a surface of stones. The whole structure seemed to occupy its own space, one of solitude and oblivion, protected from the vices of time and the habits of the birds. Inside, where the expeditionaries explored with careful intent, there was nothing but a thick forest of flowers." (p. 12)

They find a Spanish galleon. Intact. Filled with flowers. They were for the first time clearing a virgin forest, making their way, and when they arrive in the land that in the future would be their home, they discover that Spain was already there, craved in the stone soil. Here, the galleon can be interpreted as representative of the Spanish domination, which is embedded in the imagination of our lands by the invention of the narrative of a "discovery" that completely erases the history that existed here before the arrival of Europeans.

But if you are not familiar (or at least know about it) with the collective feeling of the solitude of being the result of an erased history and memory, the only thing you'll take from this scene is how beautiful it is.

And as I said before, Latin America is not the only one to use Magical Realism to translate a fantasized reality. The book Terra Sonâmbula (Sleepwalking Land), by the Mozambican writer Mia Couto (I just love this author so much), is another great example of what I'm talking about. And I won't go into this otherwise it would be very long, but just go and read it. It's amazing.

So, I think you got the hang of the ideia by now.

But what does all of this have to do with Encanto?

4. "LATIN AMERICA MAGIC"

Now that you've been covered up with all this historical contextualization and some examples above, I'll repeat what I said at the beginning: to me, Encanto is not Magical Realism. And this is due to two factors:

The magic is perceived as magic within the movie's stablished universe

The magic in Encanto is always individualized

Let's start with number 1. As I said there above, there isn't exactly a rule on this particular aspect, but it's a general consensus that for Magical Realism to happen, you can't have phrasings like "this is magic!" or "they did magic!" within your universe. As Figueiredo points out (and yes, I'll put here yet another source here, but this is only to stablish my point using more then one academic source so you don't think I'm taking this off my ass (another Brazilian saying, sorry again), in Magical Realism

"...the supernatural is presented in a realistic way, as if it doesn't contradict reason, and there are no explanations for the unreal events presented. There is no reference to the mythical imagination of pre-industrial societies, as if the author, not concerned with the reader, exercises full freedom of creation. Magic refers to inexplicable, prodigious, or fantastical occurrences that contradict the laws of the natural world, and there are no convincing explanations in the text for their presence. It differs from the fantastic in that the narrator is not altered, intrigued or disturbed by this reality." (source, translated by me)

You can see that in Sleepwalking Land, where the character Kindzu sees his brother turn into a rooster in front of him and his reaction is closer to "well that sucks, guess we gonna put him in the chicken coop now" than some astonishment.

Or in O Tempo e o Vento (The Time and The Wind, a Brazilian novel), which tells the story of generations of a family in which the fate of women is to spin, cry and wait, and where, on the return to his wife, a man ends up arriving 50 years late.

And he finds her an old woman, of course, waiting.

You can see that in One Hundred Years of Solitude, when the city is attacked by a plague of oblivion and there's no fuss over it. Or when it rains for 4 years and the old people just decide to wait to die in the drought, because they don't want to die wet. Or when a pig-tailed baby is literally carried into the earth by countless ants and no one bats an eye. Or when Remedios the Beauty had to be isolated from any contact with foreigners because her scent was so seductive and so strong that in one incident, upon seeing her naked, a man's blood turned into oils soaked in her perfume, torturing him even after death. Or when, after the death of José Arcadio Buendía, the city was covered with yellow flowers that fell from the sky, and the only reaction was that they had to mobilize people to clean the streets so the funeral procession could pass by.

In fact, the only scene in which a character in the book is truly astonished by something is when, for the first time, José Arcadio Buendía and his son Aureliano see ice.

"MANY YEARS LATER as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice." [...]

“It’s the largest diamond in the world.”

“No,” the gypsy countered. “It’s ice.”

José Arcadio Buendía, without understanding, stretched out his hand toward the block, but the giant moved it away. “Five reales more to touch it,” he said. José Arcadio Buendía paid them and put his hand on the ice and held it there for several minutes as his heart filled with fear and jubilation at the contact with mystery. Without knowing what to say, he paid ten reales more so that his sons could have that prodigious experience. Little José Arcadio refused to touch it. Aureliano, on the other hand, took a step forward and put his hand on it, withdrawing it immediately. “It’s boiling,” he exclaimed, startled. But his father paid no attention to him. Intoxicated by the evidence of the miracle, he forgot at that moment about the frustration of his delirious undertakings and Melquíades’ body, abandoned to the appetite of the squids. He paid another five reales and with his hand on the block, as if giving testimony on the holy scriptures, he exclaimed:

“This is the greatest invention of our time.” (p. 8-15)

CAN YOU FEEL THE CHILLS WHILE READING THIS? CAUSE I CAN

Magical Realism doesn't enchant us because it is magical. It enchant us because it is so raw, and crude, and so painfully real, that we feel our souls tearing apart when we come in contact with it. Just take a look at any Frida's paintings and you'll get what I mean

In Encanto, however, the "magic" is definitively perceived as magic, and it's often pointed out by MANY characters throughout the story. So, to me, that kind of breaks the Magical Realism thing.

Because it just looks like a "magic as a metaphor" situation, not anything out of the ordinary for a Disney movie. For example, how are any of the magical situations in Encanto different from, say, the ones in Beauty and the Beast? Really, it's pretty much the same idea, magic as a metaphor. And a magic house.

You even get the emotion magic going on and all

And that's super ok.

I love Disney magic. Everybody does.

So why call it differently just because it's set on Latin America?

AS FOR NUMBER 2

This might seem more of a personal opinion, and maybe it is, but this was actually one of the things that bothered me the most in this whole "Encanto is so Magical Realism" thing.

Because, as I spent 90% of this post explaining, Magical Realism in Latin America has very specific contours that are the result of centuries of troubled history. To ignore the social, historical and, above all, political undertones that the Latin works of Magical Realism have, is to ignore all the effort that this movement had in reclaiming the fantastic narrative of our own existence.

Is to ignore all the power we got by taking away from the colonizers the right to see us as "enchanted" or "magical".

And again, maybe this is a personal feeling of mine. But I can't see a work in which magic is used in such a personal and individual way by the characters as Magical Realism. As a metaphor for overload, or for personal conflicts, or for intergenerational trauma, or for singular heartache. Don't get me wrong, I loved the way Encanto created these metaphors. And they are great. I just can't fit it into everything I said above.

And I know the film DOES represents a reference to our troubled history and violence through the story of Abuela Alma. And again, this may be a personal opinion, but although I was deeply moved and cried the whole time, I don't think it was enough to frame this scene as "social criticism", or as something political.

In fact, I think this scene relates much more to the children and grandchildren of immigrants who had to leave Latin America for violent and inhumane reasons, than to us who stayed here. And perhaps that was the purpose of the film, to speak to the Latino families who were forced to diaspora. But then we are talking about another story. Not Colombia's.

I can't disassociate Magical Realism from politics, and I don't think it should be done. Because when you strip the Magical Realism from the political and historical and social contexcts, the only thing left is the "magic". And that's giving back the power to the colonizers. We are not "magical". Latin America is not "magical".

And I think that when you strip the symbols created by García Marquez from their original contexts, so carefully stitched together by him, you vastly impoverish his work.

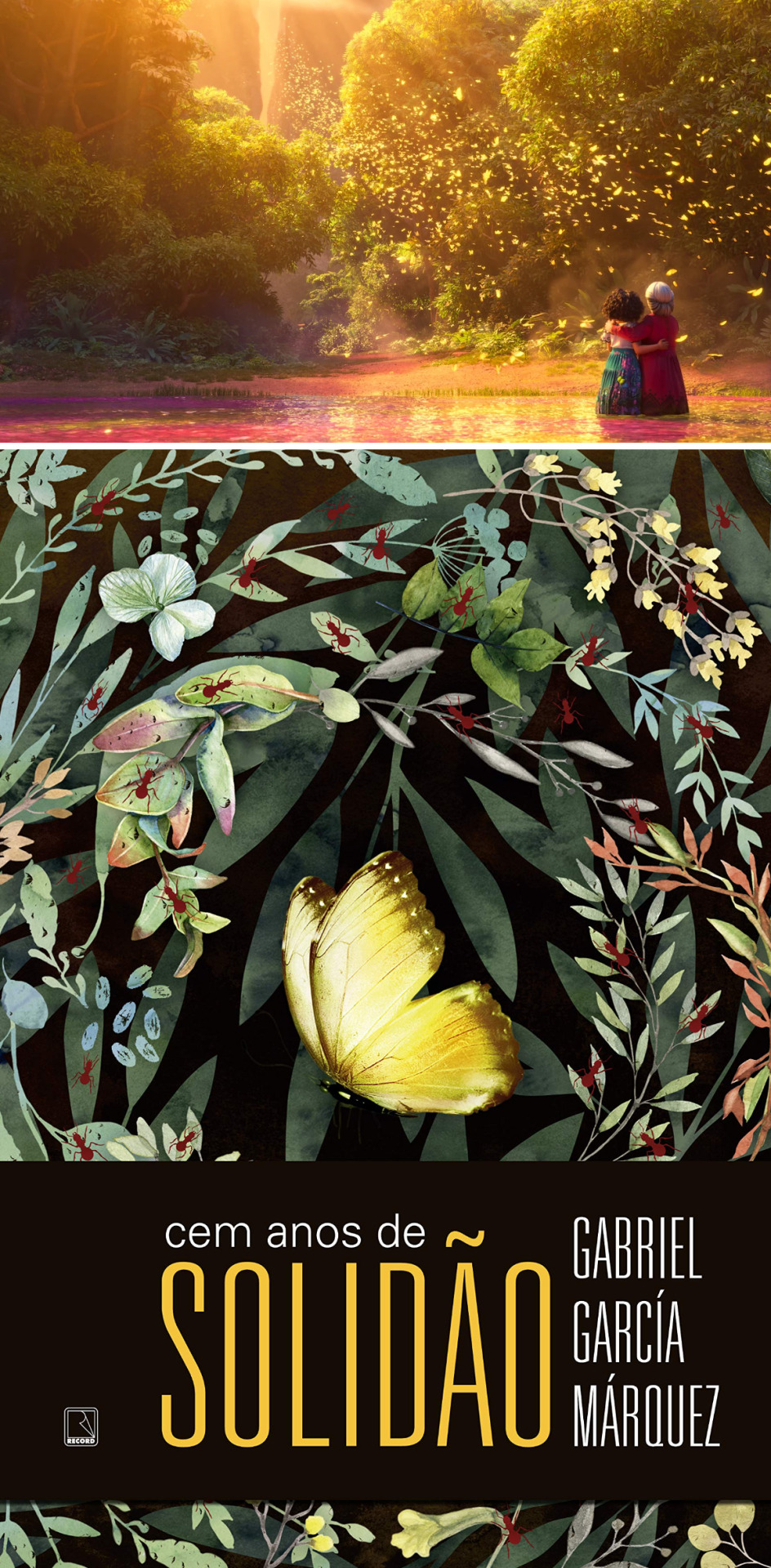

For me the best example of this is the yellow butterfly.

The yellow butterfly ended up turning into something, apparently. Not only in Encanto, but in more than one "Latin" recent work I've seen some mention of butterflies that were clearly based on One Hundred Years of Solitude (yes, All The Crooked Saints, I'm looking at you)

And you can see that there is a direct relationship between the yellow butterflies in Encanto and the yellow butterflies in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

And while there's no way to know what was going through García Marquez's head when he wrote these butterflies (only that yellow butterflies populated his grandparents' house during his childhood), the yellow butterfly ended up becoming a symbol of Latin Magical Realism.

Which is beautiful. But if you read the book, you'll see that they only appear in the narrative of the life of Renata Remedios (Meme), great-great-granddaughter of José Arcadio Buendía and Úrsula Iguarán. More precisely, the butterflies would only appear around Mauricio Babilonia.

"It was then that she realized that the yellow butterflies preceded the appearances of Mauricio Babilonia. She had seen them before, especially over the garage, and she had thought that they were drawn by the smell of paint. Once she had seen them fluttering about her head before she went into the movies. But when Mauricio Babilonia began to pursue her like a ghost that only she could identify in the crowd, she understood that the butterflies had something to do with him. Mauricio Babilonia was always in the audience at the concerts, at the movies, at high mass, and she did not have to see him to know that he was there, because the butterflies were always there." (p. 141)

The passion of Meme and Mauricio is one of the most detailed and poetic of the book. When the relationship is forbidden by Meme's mother, Fernanda, the two start to see each other in secrecy. Mauricio spends every night sneaking into Meme's quarters. And as, consumed by passion, she lives for the moment she will meet him, she waits for him lying on the bathroom floor, naked and burning with love, surrounded by scorpions. And the first sign of his arrival are the yellow butterflies coming through the window and infesting the house.

There's a line, when they're meeting at the cinema, that says:

"Meme felt the weight of his hand on her knee, and she knew that they were both arriving at the other side of abandonment at that instant". (p. 142)

The thing is, the two are lonely. And the more they sink into each other, the lonelier they get together. After Mauricio's death, the butterflies start to follow Meme, who drowns in lethargy. The yellow butterflies are, in the book, the symbol of the relationship of these two characters, who drowned their loneliness in each other's carnality. It's an intense, and carnal, and sensual, and painfully shallow relationship. And most of all, it's incredibly sad.

"Aureliano recognized him, he pursued the hidden paths of his descent, and he found the instant of his own conception among the scorpions and the yellow butterflies in a sunset bathroom where a mechanic satisfied his lust on a woman who was giving herself out of rebellion" (p. 200)

This is what was translated into the feeling of the solitude of the Latin America. Not by García Marquez himself, but by later interpretations. When I think about it, I always picture it as the feeling of the moment when, every night, Meme sees the first yellow butterfly coming through the window, and she can feel that in her gut.

And now you tell me,

why would anyone consider using this symbology in a Disney movie?

And even more, to use as a symbology of reconciliation and protection and family love? And...???

Disney my beloved??????

So, yeah, I think this movie had a lot of beautiful references to García Marquez, but taken so far from the original contexts and in such shallow ways that to me it felt more like they researched and saw that apparently yellow butterflies represent Latin Magical Realism and García Marquez and thought "wow this is lovely let's totally use that look how beautiful this is" because it looked "magical".

SO IN CONCLUSION

I like Encanto. This post is in NO WAY an attack on the film, or the Latin representation of the film. In fact, I think Encanto does a really great job at it (and as a light-skinned latina, I can stand by that very deeply).

But the statements about the magic of this movie, and the divulgation around it, and the way the producers of this movie have labeled it and approached all of this... Idk. I don't know why they felt the need to place Encanto as belonging to or inspired by Magical Realism, rather than simply telling a story that stands on its own, and happens to be set in Latin America.

I don't think the homages they paid to García Marquez were wrong or offensive in any way, in fact I thought they were all nice. I thought the yellow butterflies were beautiful, and yes, they did ended up becoming a symbol of Colombia, whether this is based on their original meaning or not. I am not complaining about the fact that they were there. What bothers me is that label. This justification that the magic of Encanto would be, somehow, different, because it was latina. That we'd have a magic that'd be different from the "European Magic".

And that bothers me even more because, I was curious enough to research to see if I was missing something, and I couldn't find ONE Latin story or legend that mentioned a magic house, for example. In Brazil we have some stories that take place in magical houses or castles (my favorites when I was a kid were "The Devil's Godchild" and "The Black Bird"), but all of these are adaptations of originally European tales. That arrived here with the European colonizers. This idea of a magical house with lots of doors and rooms bigger than the outside and fantastic things inside each of them is INCREDIBLY European. Based on European fairy tales and fables.

Aside from the fauna and flora and architecture and clothing and family dynamics the movie depicted wonderfully, there was NOTHING in the magic of Encanto that referenced or translated any folkloric magical elements of Colombian culture. I saw nothing remotely close the the La Madre de Agua, or a patasola, or a candileja, or Las Brujas de Burgama, nothing.

Why, when Disney makes a movie based in some European country, they choose fairy tales and stories from those countries to adapt, but in Latin America they ignore our stories? The legends of the native people, indigenous people, inland culture, anything?

Curious, isn't it?

But anyway, back on track. Since they didn't take an already existed tale from here, guess they thought that Magical Realism would be a good way to convey that. But they kinda didn't do that? As I said, I don't think Encanto is Magical Realism.

And honestly, if they had just made up a story that made sense and was respectful to our culture, and just placed it in Latin America (like The Emperor's New Groove, the most flawless Disney movie ever made), I think I would have enjoyed it a LOT more. But to me, it just felt like they were trying to make the whole thing about Magical Realism, without delivering it properly.

So they just made Latin America magical for the gringo eyes again.

Cheers.

SO YEAH, these were my thoughts on the subject!!! Please don't take any of it as any kind of personal attack on the people behind the movie, if there's any blame I'm more then happy to just put it on Disney Company (but we all agree on that, I think). I just wanted to tell a little of our history and explain why Magical Realism means so much to us. And you are totally free to have whatever opinion you do on this!!! RISE AND SHINE

And, as always, thank you so, so much for reading!!! ❤

#encanto#encanto 2021#disney encanto#disney#disney animated movies#meta#movie essay#magical realism#colombia#gabriel garcía márquez#cien años de soledad#latin america#history

301 notes

·

View notes