#this is also ignoring the fact that both stephen and thomas historically had to take care of wolsey's son after wolsey died

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

okay im gonna get off of steve and tom wolf hall parallels but i can't get over the whole father parallel things.

the more i think about it, the more at least in the show the whole wolsey bastard situation probably pissed stephen off because he saw how dorthea was essentially treated the same way he was treated by his own father. wolsey probably reminded stephen of his own father, in a negative way. because he had to have known about it. he probably had such a high opinion of wolsey at first, and then saw how dorthea was hushed away like a nuisance, and again, that is what happened to stephen. it's like they were both punished for being born out of wedlock.

which is so funny because the contrast to thomas is that thomas also saw wolsey as his father, a father figure who saved him and whom he loved. one who would never hurt him, and actually gave him the chance to be well, him. they were both essentially 'sons' of wolsey, sons that he had brought up, both lowborn just like wolsey but they also had such different views. and stephen started to resent him, even if in secret. at least in the show - because historically wolsey and stephen were besties.

i know we don't really develop into stephen's mind, but we know his parental situation in the book is a sore spot for him and i *think* that context is left out of the show. but that would've been another awesome parallel between them.

now tho, if stephen and thomas were friends, and stephen saw how thomas treated his own bastard now that probably would've given thomas some points in his book--

#the bastard - the black smith and the butcher's son are ideas that play in my head over and over again#the parallels were there#i mean even between all three of them#the trio was nothing but lowborn man that rose - even tho mantel likes to try and act like stephen wasn't lowborn/didn't fight to get to th#top#historically stephen and wolsey remained life long friends#but in the show there was obviously a fall out#i do think a lot of it had to do with wolsey himself#you have someone like stephen who was essentially forced into religious life and we know he didn't want to#but it ended up actually giving him the power and wealth that - given his life he deserved and fought for#and a type of stablity#in comparison#there is dorthea#who was also forced to be a nun#and in turn ended up getting the family and stability she wanted as such#and she had a lot more freedom as a woman than she would've if she was married#dorthea and stephen probably never met#but i know they both felt shelved by their fathers#mind you - stephen probably doesn't know who his family comes from#i still think he's part french#whereas his mother's side is like either scandanavian or celt#this is also ignoring the fact that both stephen and thomas historically had to take care of wolsey's son after wolsey died#and apparently that boy was expensive#im just saying the whole parentage situation is so unique to me#and his and thomas's relationship - their historical relationship#will always intrigue me#wolf hall has me in a chokehold and filling in the gaps#wolf hall#thomas cromwell#stephen gardiner

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top Ten Historical Figures Done Dirty by The Terror (2018)

So, we all know and love Dave Kajganich and Soo Hugh’s beautiful show, right? Of course. But it’s important to set the historical record straight, especially when there are real people’s life-stories and legacies on the line.

(NOTE: this list is biased heavily toward upper-class individuals because the historical record does a better job preserving those voices for us. Was the real Cornelius Hickey as nasty a person in real life as he was in the show? Almost certainly not – which is why we’re given “E.C.” as a nod to the fact that we shouldn’t assume these characters represent real historical villains, even when the narrative makes them antagonists; HOWEVER, not everyone in the show was given the same courtesy as the OG “Cornelius Hickey.” Which is why this post exists – to show you the best sides of some people you might not otherwise appreciate for their full humanity. That being said, keep in mind the sources used – and, for instance, who has surviving portraits and who doesn’t.)

Thus, below the cut, I give you this list, (mostly) in order from #10 (honorable mention, only somewhat slandered) to #1 (most hideously maligned) – my list of characters from The Terror who deserved better.

(Please don’t take this too seriously – I know there are reasons why choices had to be made in order to make this show work on television, and I do very much love the end product. But I also genuinely think it’s a good idea to remember the real people behind these characters, and think critically about how we depict them ourselves.)

Bottom Tier – The Overlooked Men of the Franklin Expedition

#10. Richard Wall – & – John Diggle

We’re combining these two because they had a lot in common, historically speaking! Both were polar veterans, having served as a Cook (Wall) and an AB-then-Quartermaster (Diggle) on HMS Erebus under the command of Sir James Clark Ross in the Antarctic expedition of 1839-1843. Certainly we do get some good scenes with them in the show, but there was plenty more to explore there – for instance, Captain Ross was apparently so taken with Richard Wall that he hired him on as a private cook after the Antarctic expedition. (One imagines that Sir James may have regretted letting his friends of the Franklin expedition steal Wall out from under him.)

(If you want some more information on Diggle, the brilliant @handfuloftime found this excellent article on him – fun facts include the detail that Diggle’s only daughter bore the name Mary Ann Erebus Diggle.)

#9. John Smart Peddie

Now, I don’t think we should go as far as the Doctor Who Audio Drama adaptation of the Franklin Expedition, which makes Peddie into Francis Crozier’s oldest friend, someone “almost like a brother” to Crozier (no evidence of ANY prior relationship between the two existed, contrary to whatever the Doctor Who Audio Dramas would have you believe!) but Peddie probably earned his place as chief surgeon, however fond we may all be of the beautiful Alex “Macca” MacDonald, who was, in fact, the Assistant Surgeon, historically speaking. It’s hard to find information about Peddie, but someone should go looking! I want to know about this man!

(If you want to know more about the historical Alexander MacDonald, there’s a short biographical article on him from Arctic that you can read here.)

#8 James Walter Fairholme

The only one of the expedition’s lieutenants who doesn’t really get any characterization in the show, which is a travesty! The historical Fairholme (pronounced “Fairem”) was, as they say, a himbo, and the letters that he wrote home to his father are positively precious. He loved the expedition pets (lots of kisses for Neptune!), and he needed two kayaks because he couldn’t fit into just one with his beefy thighs. Fitzjames loaned him a coat when all the Erebus officers had their portraits taken, and then called him a “smart, agreeable companion, and a well informed man,” and Goodsir singled Fairholme out as “very much interested” in the work of naturalist observations. Just a lovely young man who could have gotten some screen time, you know?

(Also, as @transblanky discovered, four separate members of the Fairholme family gave money to Thomas Blanky’s widow when she was struggling financially in the 1850s, making them, combined, the most generous contributor to her subscription.)

Middle Tier – Franklin’s Men Who Didn’t Deserve That

#7. William Gibson

Alright, I want to talk about how uniquely horrible the show’s William Gibson is: this is a character willing to lie and accuse his partner of sexual assault that didn’t happen. I get there were extenuating circumstances, but if I were a historical figure who died in some famous disaster and someone depicted me doing something like that? Let’s just say I’m deeply offended on the real Gibson’s behalf.

What do we know about the historical William Gibson? Not much – but we know a little. Gibson’s younger brother served on an overland exploratory venture across Australia in the 1870s… from which he never returned. (God, the Gibson family had the worst luck?) This description of a conversation that young Alf Gibson had with expedition leader Ernest Giles only days before his death is VERY eerie:

[Gibson] said, “Oh! I had a brother who died with Franklin at the North Pole, and my father had a deal of trouble to get his pay from government.” He seemed in a very jocular vein this morning, which was not often the case, for he was usually rather sulky, sometimes for days together, and he said, “How is it, that in all these exploring expeditions a lot of people go and die?”

I said, “I don't know, Gibson, how it is, but there are many dangers in exploring, besides accidents and attacks from the natives, that may at any time cause the death of some of the people engaged in it; but I believe want of judgment, or knowledge, or courage in individuals, often brought about their deaths. Death, however, is a thing that must occur to every one sooner or later.”

To this he replied, “Well, I shouldn't like to die in this part of the country, anyhow.” In this sentiment I quite agreed with him, and the subject dropped.

(From Giles’s Australia Twice Traversed which you can read here)

Beyond that, one thing we do know is that William Gibson was probably friends with Henry Peglar – they had served on ships together before, and Gibson may possibly have been the poor fellow found cradling the Peglar Papers, according to researcher Glenn Stein. So we might imagine the historical Gibson as a much kinder man than the show’s depiction of him – this was someone who befriended the clever, playful Peglar we all know and love from the transcriptions of his papers, so full of poetry and linguistic jokes. It’s a shame we didn’t get a chance to meet this real Gibson, who actually knew the Henry Peglar whom we love so well.

#6. Stephen Stanley

Look. There’s that one famous line in James Fitzjames’s letters to the Coninghams about how Stanley went about with his “shirt sleeves tucked up, giving one unpleasant ideas that he would not mind cutting one’s leg off immediately – ‘if not sooner.’” And certainly Harry Goodsir had some mixed opinions of the man, saying was “a would be great man who as I first supposed would not make any effort at work after a time,” and that he “knows nothing whatever about subject & is ignorant enough of all other subjects,” whatever…. that means….

But Fitzjames also had some rather nicer things to say about him, that he was “thoroughly good natured and obliging and very attentive to our mess.” Also, the amputation comment? Very likely had a quite positive underlying joke to it – Stanley may not have been much of a naturalist, but he was actually an accomplished anatomist, who won a prize for dissection in 1836, on account of his “bend of the elbow,” which was “a picture of dissection,” according to Henry Lonsdale, who also called Stanley his “facetious friend” and “a fine fellow” (Lonsdale 1870, pg. 159). So, the real Stanley probably was rather droll, but the perpetually cruel Stanley of the show misses some of the real man’s major historical virtues and replaces them with historically unlikely mass-mercy-murder.

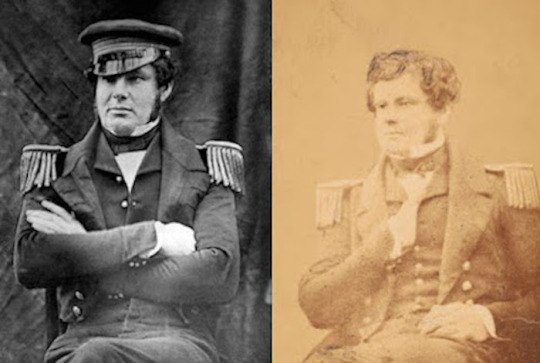

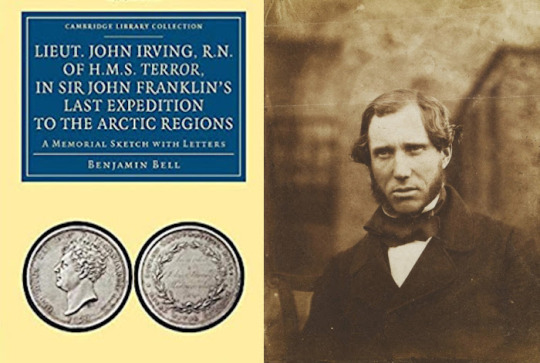

#5. John Irving

Now we’re getting into the territory of characters who did get some good development, but are missing a bit of historical nuance. As I’m sure many of you know, the historical Irving was indeed very religious, but the flashes of anger (i.e. against Manson) we see from Irving in the show don’t seem terribly consistent with the Irving depicted in this memorial volume, where John seems more like a quiet, bookish, mathematically inclined young man, with a self-deprecating sense of humor and a gentle sweetness. It’s really not at all far off from the version of Irving we see with Kooveyook in the show – I just wish we could have seen more of that side of Irving.

Top Tier – The Triumvirate of Polar Friends

So, these three DO have many good things to recommend them in the show, but because I’ve done such deep research on them, it can be quite jarring to watch certain scenes in which they behave contrary to their historical personalities, and I find myself pausing when watching the show with friends or family to explain that NO, they wouldn’t do that!

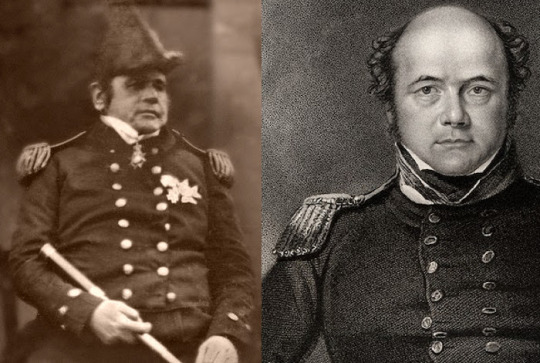

#4. Sir James Clark Ross

First thing – we LOVE Richard Sutton. He did a beautiful job with the material given to him. (This is true of all the actors on the list, frankly, but it’s doubly true here.) But that scene at the Admiralty where Sir James tells Lady Franklin “I have many friends on those ships, as you know,” to shut down her argument for search missions? At that time (aka 1847), historically, Sir James Clark Ross was actively campaigning for search missions, planning routes and volunteering his services in command of any vessel the Admiralty even vaguely contemplated sending out. You could see this real-life desperation in Sir James’s morose attention to his whiskey glass in that scene if you’re really trying, but I think the more historically responsible thing would have been to make vividly clear that James Ross risked life and limb, as soon as he possibly could, to try to rescue Franklin and Crozier and Blanky, men he’d known and cared about and bitterly missed – and, in the case of Crozier, “truly loved.”

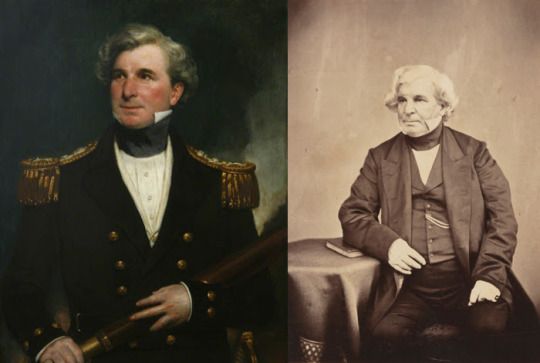

#3. Sir John Franklin

The historical Franklin had plenty of flaws – his contributions to British colonial rule certainly harmed no small number of people, and we should question the way that heroic statues of Franklin are some of the only memorials that serve to honor the lives lost on Franklin’s expeditions – especially considering the steep body count of not only Franklin’s final voyage, but his previous missions in Arctic regions as well. (DM me and I’ll scream at you about counter-monuments! Is this a promise or a threat? Who knows!) With that said, most contemporary accounts agree that Sir John Franklin treated his friends, his family, and those within his social orbit with kindness, and his cruelties were systemic, not personal. In this light, the image of Sir John viciously tearing into Francis Crozier’s vulnerabilities in the show feels very off. Though there was certainly some friction over Crozier’s two proposals to Sophia Cracroft, historically speaking, there’s no evidence at all that Sir John discouraged her from marrying Francis – Sophia may have had many reasons of her own (*clears throat meaningfully in a lesbian sort of way*) for not accepting any of the several marriage proposals offered to her (from Crozier as well as from others), and we ought to keep in mind that she remained unmarried all her life. The notion that the real Sir John would have considered Crozier too low-born or too Irish to be part of the Franklin family isn’t grounded in historical fact.

#2. Lady Jane Franklin

Again disclaimer: the real Lady Franklin left behind a legacy with much to critique. Those who rightfully point out the racism of her treatment of the young indigenous Tasmanian girl Mathinna should be fully heard out. Observations of her own contributions to imperialism are important and valid. Though I tend to see her feud with Dr. John Rae as somewhat understandable – given that Lady Franklin didn’t have the benefit of our hindsight knowing Rae was correct – the levels of prejudice that she enabled and even encouraged in the writing of Charles Dickens when he attempted to discredit Inuit accounts of Franklin’s fate are inarguably deplorable. These things being said, everything noted for Sir John re: Sophia Cracroft goes for Lady Franklin as well – there’s no reason to imagine a scene where Jane would bully Francis Crozier within an inch of his life, seconds after a failed second proposal, when, historically, Lady Franklin felt the situation was so delicate that it required the quiet and compassionate intervention of Sir James Clark Ross, a dearly loved mutual friend to all parties. Tension does not imply aggression; conflict is not abuse. We know this can’t have been an easy experience for the historical Francis Crozier, but the picture is a lot more complicated than what can be shown in one small subplot of a ten-episode television show. Because of this complexity, however, Lady Franklin’s social deftness suffers in the show. (I could also write an entire essay about Jane Franklin’s last shot in the show, at the beginning of Episode 9: The C the C the Open C – TL;DR is that framing is very important, and, at the very last moment, the show reframes Lady Franklin as a mutilated corpse, a speaking mouth without a brain, which is….. a choice.)

And, at number 1, the person done most dirty by The Terror (2018) is….

#1. Charles Frederick “Freddy” Des Voeux

Look. I’m biased here because I am fed daily information about the historical Freddy Des Voeux from @frederickdesvoeux so I’ve become, I think understandably, a bit attached.

But this is very plainly the clearest cruelty the show does to a historical figure – the historical Des Voeux was a very young man (only around 20 when the ships set sail) known always as “Frederick or Freddy” to his family, and described by all parties as bright and sweet – Fitzjames said that he was “a most unexceptionable, clever, agreeable, light-hearted, obliging young fellow, and a great favourite of Hodgson’s, which is much in his favour besides,” and described him cheerfully helping to catch specimens for Goodsir. Des Voeux is named “dear” by Captain Osborn in Erasmus Henry Brodie’s 1866 poem on the Franklin Expedition (43) and Leo McClintock reported the young man’s well-known “intelligence, gallantry, and zeal” in his 1869 update to his account of the Franklin Expedition’s fate (xlii). None of this is consistent with Des Voeux’s behaviour in the show, especially in the later episodes.

To reduce Des Voeux to an easily-detested figure, over whose death one might cheer, is not a kindness – the creation of a narrative where his death is satisfying does damage to the memory of a real person, a barely-more-than-teenager who died in the cold of the Arctic and left behind only scraps of a shirt and a spidery signature in the bottom margin of a fragmentary document.

Television shows may need their villains, but it’s important to remember that real life isn’t like that. Surely the historical Frederick Des Voeux was most likely not a perfect person, and, as an upper class officer contributing to a British imperial project, he does bear some responsibility for the harm done by the Franklin expedition, but it’s not accurate to assume he was any less worthy of sympathy than the other officers who considered him a friend – those men whom we now venerate, like James Fitzjames. So as far as I’m concerned, Freddy Des Voeux deserves at least as much consideration, care, and compassion from us.

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

Second ‘When Christ and His Saints Slept’ reaction post (part one here), covering chapters 11 to 20 aka the bit where I start shipping actual historical figures for the first time ever (other than Wars of the Roses-era people, but that’s different because they were actually married and it wasn’t a ship ship in the same way these are. Anyway.)

Chapters XI and XII:

Annora and Ranulf still love each other :) and they found a loophole so they can get married when Maude's queen! I really should've remembered about that plight-troth. Now a bit worried about all the ways this could go wrong, not least because I'm aware Maude doesn't become queen, but that was really sweet and I'm glad they're happy and things have been resolved (ish)

UGH, GEOFFREY. He's being awful about Maude and Henry's overhearing :(

Between the odd mentions of her here and what little I know about her historically, I'm so excited for when Eleanor of Aquitaine shows up!

Whoops, Chester. Genuine anger and a lack of mercy from Stephen may be a rare thing, but I have a feeling this has crossed the line.

I like it when Maude has interactions with people she likes and trusts - her brothers, Adeliza, and now Brien. It's good.

...okay I might be starting to ship this.

Oh dear I'm definitely shipping this. It's impossible and a mess and they both (Maude especially) seem like they'd rather be swallowed by the earth than actually admit to feelings, but it's so sweet and they trust each other so much and must have such a long shared history? Help?

And also lbr this is just That One Dynamic that absolutely kills me in every piece of media. The mutual trust, the quiet but unbreakable loyalty, the circumstances making things so difficult for them? This is absolutely my thing.

This might be the first time I've actually shipped people who existed. Like, there were some good moments in TSiS but all with people who were actually couples in real life. But with this, I don't know many of the specifics, I have no idea what happens to Brien and only know slightly more about Maude. This is strange.

AAAAAHH. Maude you can't do this to my heart. You just can't.

Chapter XIII:

I like Robert.

Hmmm. Looking at both sides' chances in this battle, and knowing Stephen gets captured at some point during the Anarchy, I have a feeling I know how this will end.

Why does it feel like the awful déjà vu of this part was intentional. This is making me have Bosworth-related emotions all over again.

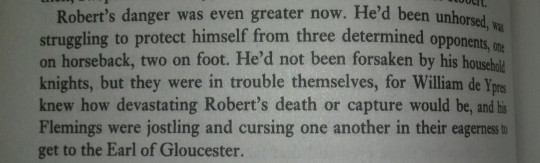

Okay, wow, that was all quite a lot to take in. Chester's plan was good, and I'm grateful that he saved Robert; wasn't expecting William of Ypres of all people to flee*; Stephen's determination is also making me remember Bosworth in TSiS; I liked the bit with him and Robert and Ranulf at the end.

Chapters XIV and XV:

Aww, family (Maud and Robert and Ranulf)

Maude :')

Matilda just found out about Stephen :(

Maude's going to have trouble winning over the people. London's apparently still loyal to Stephen, and their favour was often an advantage in struggles like this war (looking at you, Edward IV)

I'm feeling more sorry for Constance with every scene she's in or mentioned. Things just keep getting worse for her.

William de Ypres just showed up; Matilda is (understandably) furious about the Battle of Lincoln and letting him know it.

Alliance time! This is one of the things I was vaguely aware of before starting the book, and the anticipation of it has been a lot of fun. Also, I like how honest he’s being here - he made a choice, realised/decided it was the wrong one, and is making no excuses, instead being clear that he wants to try and make things right. The contrast with, say, Bishop Henry’s total lack of self-awareness (or maybe it’s wilful ignorance?) about his moral bankruptcy is wonderful.

Chapters XVI and XVII:

My ship! They're interacting!

HAND. KISSES. My weakness. I know they're the norm and not necessarily romantic at this time but still.

I am deceased. This ship has killed me and they've only had two direct conversations.

Bishop Henry is possibly about to switch sides. Again. I ought to keep track of who’s betrayed both sides the most times (probably him right now).

It's been four months since Matilda joined forces with William de Ypres to try and save Stephen, I wonder what they've been up to? (They haven’t been mentioned in the novel since then)

Everything about this:

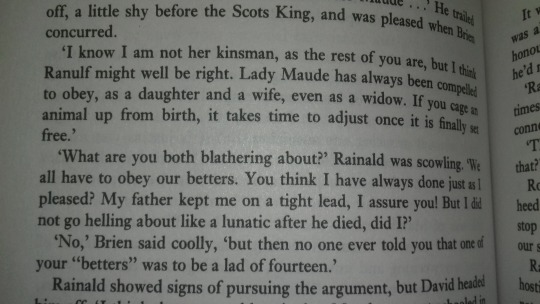

and then THIS:

I love this conversation for so many reasons. Most of which involve Maude and Brien because apparently now I’ve dedicated my life to being emotional about them.

Matilda!!! It’s been too long.

Okay, so based on Northumberland's thoughts:

hmmm, new ship?

they're using nicknames they're being familiar this feels like a Big Deal for people in their position at that time. It’s certainly a level of informality that very few others have in the book so far.

Wait they just mentioned a Thomas Becket. Is he that Thomas Becket? I know his feud was with Henry II, whose reign begins in about fourteen years, so it's possible.

I love every mention of the chronicles. It's really cool having the regular narration of the novel interspersed with little pieces of old accounts.

I also love the little moments like Ypres here and his quiet admiration of/confidence in Matilda.

Chapter XVIII:

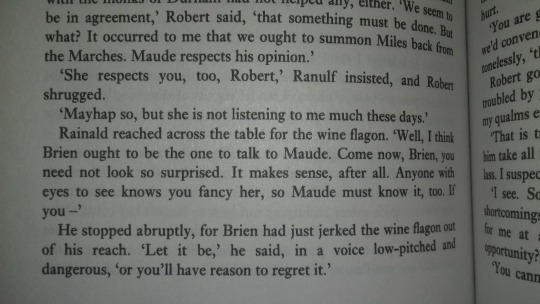

Not content to just leave me to deal with my feelings from the last few pages, the chapter opens with this:

Immediately following that last part, we now switch to Matilda’s thoughts about de Ypres? He’s trying to hide his exhaustion and she’s not having it? Literally standing over him to make sure he eats? Fond??? Yup, I'm definitely invested in it now. These relationships will be the death of me.

Stephen listing Ypres as one of the people who he could never expect to help Matilda :')

And he's just found out about their alliance!

The guard saying "No one knows how your lady won him over" before being cut off is just really funny. I'm just picturing all of England in total confusion about how Matilda managed to get this cynical, battle-scarred mercenary's unwavering loyalty after Stephen couldn't manage the same. Just. The entire country, collectively looking at this alliance and going '???'

"I had my own miracle all along. I'd married her!" Stephen you cinnamon roll you're completely right

Maude and Brien Maude and Brien Maude and Brien Maude and Brien Maude and Brien Maude and Brien

:DDDD

...I have become hopelessly obsessed. This book has two ships that are my favourite dynamic. Two. This is turning into Code Geass all over again.

(The dynamic is "mutual trust, admiration and respect; if there are romantic feelings, they might be ambiguous and possibly not acted on for any one of a number of reasons, most of which can be summed up as ‘external circumstances getting in the way’; absolute loyalty through thick and thin; help each other grow and get through difficulty; one or both is probably also a little scarred by the world". Bonus points if they have a long history, or any period of time spent together that’s not fully described in canon and can therefore be speculated about.)

Chapter XX (and some reflections on XIX):

The thing about recognising Matilda’s habits:

made me think immediately of this post

Hell yeah teaming up to get Chester to leave.

Ypres just internally being like “oh god I’m actually caring about someone’s emotional wellbeing what is this what do I do”:

(also “the one man she trusted not to lie to her” is sweet but it’s also kind of upsetting that Matilda’s surrounded by allies and yet knows she can’t fully trust most of them)

my heart???

Some of my favourite ships are the ones where I don’t even know if I see it as platonic or romantic, just that these people have such deep affection and trust for each other and it’s wonderful. This is absolutely one of those ships.

I’ve not written anything about the destruction(s) of Winchester, mainly because this book is once again difficult to put down, but suffice to say that it’s pretty harrowing. Seeing things from the perspectives of Maude and Matilda, who haven’t witnessed this side of the war up close before and are feeling responsible for everything awful that’s happening, as well as Ranulf, who’s similarly horrified and hasn’t seen this kind of destruction before, possibly makes it even worse. Also I love the occasional scenes from the point of view of ordinary citizens – it really makes the wider effects of this civil war between cousins sink in. This may have begun as a personal tragedy for Maude, Stephen and their loved ones, but it’s become a catastrophe affecting so many more people across England, Normandy, Anjou…the fact that the narrative brings in the thoughts of people from all across society in recognition of this is one of the things that makes this book so good imo.

Okay, so I’m getting very attached to quite a lot of these people and it’s occurred a few times that I don’t actually know the dates of death for anyone except Stephen. But because this is history and also the first book in a trilogy spanning many decades and the characters are (as far as I know) not immortal, they’re all going to die at some point. I just don’t know when. There is no way to be prepared for the sadness that this book and its sequels will bring.

OH NO RANULF

At this point he should really just stop trying to break into nunneries. As Gilbert mentioned, it never seems to go well.

Wait, if they’re specifying not to kill Ranulf does that mean everyone else who was with him was killed? FEAR

Okay good there are more survivors

That fire was awful. Although I’m going to keep in mind that Gilbert and Marshal are only dead according to the people outside the church – the narration moved away from them when Marshal lost his eye, so there’s still hope (albeit not much). Also, this really showed both sides of de Ypres – he’s managed to be merciful and ruthless in the same paragraph.

Ancel!

And Ranulf is free, but with a hefty dose of survivor’s guilt.

Awww, Maude’s really openly relieved he’s safe. Robert too.

Gilbert’s alive too! I’d suspected but wasn’t sure. Glad for him and Ranulf that they’ve got each other back.

*I’d known that he’d abandoned a battle at some point before allying with Matilda, but had thought that referred to his feud with Robert during the Normandy campaign, which was briefly mentioned earlier, so this came as a surprise.

#when christ and his saints slept#sharon penman#witness my slow descent into madness#a solid 90% of which is thanks to about five characters#and the realisation that this book contains That Dynamic#that I'm always weak for#iz.txt#penmanblogging

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Symposium: A splintered court leaves the Bladensburg Cross intact

Ira Lupu is F. Elwood & Eleanor Davis Professor of Law Emeritus at The George Washington University Law School. Robert Tuttle is the David R. and Sherry Kirschner Berz Research Professor of Law and Religion, also at the GW Law School.

In The American Legion vs. American Humanist Association, the Supreme Court considered whether the establishment clause barred a government-sponsored display of a 40-foot cross, known as the Bladensburg Cross, on public land, as a memorial to men of Prince George’s County, Maryland, who had died in World War I. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit, applying the well-known and long-derided three-part test from Lemon v. Kurtzman, had held in 2017 that the display unconstitutionally endorsed Christianity and ordered its removal from public land. Seven justices voted to reverse, so the Bladensburg Cross will remain in place. But the case produced six separate opinions, and it reveals that the court remains starkly divided on fundamental questions about the meaning of the establishment clause. Lower courts will quickly note that governing standards in cases involving religious displays have changed, but what will emerge remains far from obvious.

Justice Samuel Alito wrote for the court. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan and Brett Kavanaugh joined the parts of that opinion that focused on the facts and circumstances surrounding the Bladensburg Cross. They argued that the cross has taken on for many a secular meaning because of its age, its continuity, and the historical context of World War I. This meaning includes the sense that the cross had become “a symbolic resting place for ancestors who never returned home . . . a place for the community to gather and honor all veterans and their sacrifices for this Nation, . . . and a historical landmark.” Removing it (or forcing its transfer to private hands) would seem hostile to religion. Under these circumstances, the court wrote, continued display of the cross did not violate the First Amendment.

In parts of the opinion joined by only four justices (Alito, Roberts, Kavanaugh and Breyer), a plurality addressed a set of general questions about the standards to be applied in the future. Section II-A argued that the test of Lemon v. Kurtzman – inquiring into secular purpose, secular effect and entanglement between the state and religion as a way of measuring establishment clause violations – had been systematically ignored by the Supreme Court and should no longer guide the lower courts in evaluating religious displays. Section II-D – relying on decisions, including Town of Greece v. Galloway, about public prayer at government meetings — argued that the appropriate tests involved the history and tradition of religious messages in public life. (Kagan, who had prominently dissented in Town of Greece, did not join sections II-A or II-D.)

These prayer practices, the plurality concluded, “stand[] out as an example of respect and tolerance for differing views, an honest endeavor to achieve inclusivity and nondiscrimination, and a recognition of the important role that religion plays in the lives of many Americans. Where categories of monuments, symbols, and practices with a longstanding history follow in that tradition, they are likewise constitutional.” The Bladensburg Cross display, five justices (including Kagan) seemed to believe, satisfied these principles.

Kavanaugh wrote separately to emphasize his agreement that the court had effectively discarded Lemon in all establishment clause disputes, about displays or otherwise. Breyer, joined by Kagan, concurred to emphasize the vintage (90-plus years) of the Bladensburg Cross; the divisiveness that would follow from a court ordered removal; and their agreement that the cross manifested no “deliberate disrespect of non-Christians.” Kagan, writing only for herself, emphasized her unwillingness to abandon the inquiry into secular purpose and secular effects.

Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas concurred only in the judgment. Thomas repeated his frequently expressed views that the establishment clause applies only to the federal government, and that only coercion to engage in religious experience violates the clause. Gorsuch (joined by Thomas) argued that observers of religious messages and symbols, including the Bladensburg Cross, lack standing to challenge these displays. Gorsuch added that he had trouble seeing why new religious displays should be evaluated any differently than old ones. In the Gorsuch-Thomas constitutional world, politics rather than law would be the only measure of the permissibility of religious displays by government.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, dissented. They reaffirmed their commitment to establishment clause norms that preclude government sponsorship of a particular faith. And they insisted that the display of a cross as a war memorial cannot be re-rationalized as a secular, generic or universal symbol of sacrifice in wartime. The cross belongs to Christians as a symbol, and excludes others.

A result-oriented failure of reasoning

We find it hard to read the five justices’ opinion for the court as anything other than sheer rationalization, in the worst meaning of that word. Those justices quite transparently looked for a way not to affirm the 4th Circuit’s judgment. They might have relied narrowly on Breyer’s concurring opinion in Van Orden v. Perry, arguing that removal of an old religious monument would cause intolerable strife. Such reasoning would have been understandable, even if it exposed its own purely political character.

Instead, the court opinion engages in exactly the type of lawyers’ history and social psychology that four justices find objectionable in the Lemon test. Somehow, the court determines that, over time, a predominant Christian meaning of the Bladensburg Cross has been replaced by one that focuses on the “sacrifice” of American soldiers in World War I. The court’s presumption of constitutionality for old monuments also shelters all “cross shaped memorials” related to that war.

The court’s own historical citations betray the weakness of this reasoning. Immediately after World War I, commentators regularly claimed that the United States was a “Christian nation.” In that cultural and political milieu, what commemorative symbol would one choose other than a cross? As the court recites, the dedication ceremony’s keynote speaker proclaimed the cross as “symbolic of Calvary” and fitting tribute to those who gave their lives in a “righteous cause.” The Latin Cross is not a randomly chosen symbol. For those who believe, it represents – both then and now – the unique event of Jesus’ crucifixion, and God’s subsequent resurrection of the Son in triumph over death.

The court’s opinion suggests that some new public meaning, its derivation undeclared, has sufficiently muted the uniquely Christian character of the Latin Cross. By the magic of history and tradition, that sacrifice has transcended Christianity. Some Christians may celebrate this decision, but it should instead be mourned as a political misappropriation of a powerful symbol of Jesus’ redemptive death.

Going forward, the effort in the Bladensburg Cross case to renovate establishment clause standards will cause a new round of uncertainty in the lower courts. As the 4th Circuit understood, the “endorsement” test was a gloss on a Lemon-based inquiry into the purpose and effect of a religious display. The repudiation of Lemon by at least six justices will make it highly unlikely that the “endorsement” test as a measure of constitutionality will reappear.

What will take its place? The emphasis in the Bladensburg Cross case on the age of the display and its World War I vintage suggest strongly that the contextual analysis associated with the endorsement test has not been abandoned. Moreover, the court’s apparent emphasis on inclusivity, mutual respect and nondiscrimination in government religious messages – however hollow that emphasis may seem in connection with the display of a 40-foot-tall Latin Cross as a memorial to war dead – may lead lower courts to continue to struggle with seasonal holiday displays, and with more permanent displays that sharply favor Christianity or any other faith. A presumption of constitutionality for longstanding displays does not tell judges how to evaluate new ones, nor explain what evidence is sufficient to overcome that presumption for old ones. The only predictable change is the candid substitution of the judge’s own perspective about history, tradition and inclusivity in place of the always imaginary perspective of the “reasonable observer.”

More broadly, it has been obvious for years that different establishment clause contexts – including religion in public schools, government funding of religious experience, permissive accommodation of religion and concerns about government interference in ecclesiastical matters — are each governed by their own discrete line of cases. The lower courts perceived this; only in cases about religious displays had the scent of Lemon strongly lingered. The Bladensburg Cross case will change the nomenclature of standards, but will not eliminate case-by-case consideration of the context of displays. Despite the sadly predictable result in the Bladensburg Cross case, at least seven justices continue to pay tribute to themes of religious egalitarianism and pluralism. With or without three-part tests, those basic establishment clause concerns will inevitably play a role in the controversies to follow.

The post Symposium: A splintered court leaves the Bladensburg Cross intact appeared first on SCOTUSblog.

from Law https://www.scotusblog.com/2019/06/symposium-a-splintered-court-leaves-the-bladensburg-cross-intact/ via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Text

Bird Viewing Areas On The Maryland, Delaware Eastern Bank.

Many people worldwide recognize The Goodyear Blimp coming from TV, the 'eye in the sky' at essential showing off places. Water, though utilized for a lot of cleaning ventures, may leave behind some undesirable blemishes of its personal. Window Rehab Quick Guide for Historic Properties. Because the city rejected to utilize loan coming from the health-care Stablizing Fund for the cost savings, both celebrations entered speak about the perk adjustment deal. In Twentieth-Century Building Materials: Background as well as Preservation, revised through Thomas C. Jester, 182-87. They can only reside less than a day without it, and water worry may lead to laying chickens to quit generating. If you have actually taken care of to make it through the meals readied in unclean problems and also produced it past crowds of spitting individuals, you are going to at some time need to make use of a social toilet. Potential Anterior: Diary of Historic Conservation, History, Theory, and Criticism 6 (2 ): 58-73. Search for nontoxic choices like reduced VOC paint or even environment-friendly cleansing items. In the daytime, the city comes to life as well as is your normal busy Colombian town along with plenty of industrial retail stores and food items alternatives. Our experts were often launched misuse through Chinese people on the street. Cleansing the home windows in your auto is very easy along with check this site out basic and also environment-friendly window cleaning recipe. Among Europe's a lot of vibrant metropolitan centers, Germany's capital and social center, is actually a must-visit deter on any European city excursion.

Jonge, Wessel de, Arjan Doolaar, as well as International Working-Party for Paperwork and Preservation of Structures Websites as well as Areas of the Modern Activity. Take a travel via the Motorcity and also you'll view why it is among the most awful metropolitan areas in Michigan to stay. IT IS A STUNNING CITY OF PLENTY OF GOOD PLACES.I ADORED IT TOO MUCH WAS DISNEY PARK. On December 8, 2015, a 14-0 ballot provided the Los Angeles Common council's validation to the advanced Clean Up Eco-friendly Upward measure. Carpet cleaning everyday assists in sky top quality improvement that indicates a lot less ill times for staff members as well as boosted efficiency for your business. Produce note of the specific solutions the customer is actually looking for such as emptying rubbish, cleaning, toilet cleansing, vacuuming and also mopping. Industrial Properties: Preservation and also Regrowth. Leading features within the Bug 'half' of city include the lovely Parliament building (the concept of which is based on your homes of Parliament in Greater London), St Stephen's Basilica, and also the reasons of Vajdahanyad Castle. Advanced Blood Electrical Power (APP) utilizes a process they refer to as Gasplasma to transform household and also toxic waste products right into tidy burning synthetic gas as well as heavy duty development product they call Plasmarok. Kept mine for a decade, photographing totally in monochrome both at college and also in New York. On Monday 21st July 1919 the Wingfoot Air Express (had by the Goodyear Tire as well as Rubber Firm) crashed into the Illinois Rely On and also Discount Property in Chicago, with the loss of thirteen lifestyles. Individuals who reside in eco-friendly residences ought to not make use of extreme chemicals. Dictionary of Building Conservation. I don't ignore the chances I have been offered or even the truth that many individuals, black and white, defended and also at times craved me to possess these rights. Of the Inner Parts, National Park Service, Maintenance Aid Department. The traditional place black household, meanwhile, makes just under $28,000 yearly. I am actually actually depressing for so many people detest Mandarin. The distinguished public bathrooms in Rome and in much of the various other crucial areas were gifted individually by the ruling emperor and also were a means of worrying his greatness, energy and also condition.

Schooling is actually intensely affected where the African American afro-americans are actually not made it possible for to mix up with whites in universities. Coming from the Law of Freedom to Ellis Island to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Area never rests due to the fact that its own locals have so much to perform each day.

0 notes

Text

[Ilya Somin] Democracy is Not the Central Value of the Constitution

Efforts on both right and left to make the democracy-promotion the key focus of constitutional law should be rejected.

There is a long history of efforts to show that the the promotion of democracy is the main purpose of the Constitution, and should be the primary focus of constitutional interpretation today. On the right, the late Judge Robert Bork, among others, defended originalism in large part on the grounds that it supposedly conducive to democracy, or at least more democratic than living constitutionalism. On the left, the great constitutional theorist John Hart Ely argued that most, if not all, the major provisions of the Constitution, are there to promote effective democratic representation, and should be interpreted with that purpose in mind. More recently, Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer has argued that "making our democracy work" should be the main focus of judicial review (though his own jurisprudence is not always consistent with that theory).

In an insightful recent post, Northwestern law Professor John McGinnis takes issue with such claims:

The original Constitution, including the Bill of Rights, puts some very important rights beyond the reach of a representative federal government. The Fourteenth Amendment adds other important rights and puts them beyond the reach of state governments as well. Thus, it is hard to say as a general matter that the Constitution should be interpreted to advance representative government or to advance specified rights.

Some have argued, most famously John Hart Ely, that most of the rights provisions in the Constitution are democracy reinforcing, thus suggesting that democracy is the key concept for interpreting the Constitution. I do not believe this claim is right as matter of original understanding. Free speech is surely conducive to representative government. However, that does not mean it was meant to be instrument of it, rather than a protection of an individual right, as I have argued elsewhere. Free speech also appears in an amendment with the right of free exercise of religion, which is not democracy reinforcing but individually empowering. And other rights in the Constitution, like those guaranteed by the Contract Clause in the original Constitution and the Privileges or Immunities Clause in the 14th Amendment, protect rights that cannot be understood as designed to reinforce rather than to restrict democracy.

The danger of using democracy as a structural principle is that it will become a weapon to limit constitutional rights. Both right and left fall into this trap. Robert Bork used the democratic principle to limit the reach of the First Amendment to political speech. Liberal Supreme Courts justices today claim that considerations of democracy now can be used even to limit political speech. For similar reasons, the contentious question of judicial deference versus engagement cannot be resolved by appeals to democracy, even if it can settled in other ways, as I have discussed here.

In the same post, John also includes a helpful explanation of why the Constitution's guarantee of a "republican" form government to the states should not be interpreted as a commitment to broad-ranging majoritarian democracy.

John's list of constitutional rights that constrain democracy at least as much as they reinforce it can easily be extended: the property rights protected by the Takings Clause, the Eighth Amendment's ban on "cruel and unusual punishment," various procedural rights for criminal defendants, Second Amendment protections for the right to bear arms, and a variety of restrictions on racial, ethnic, and religious discrimination that may be (and historically often have been) supported by democratic majorities. In addition to individual rights, a number of structural elements of the Constitution restrict majoritarian democracy, as well. The unequal apportionment of the Senate is an obvious example. Federalism may be another, in so far as it restricts the power of national majorities (though it also in many instances helps empower state-level majorities).

Conservative originalists who seek to defend originalism by reference to democracy are barking up the wrong tree, in so far as much of the original meaning actually restricts democracy, and in many cases was intended to do so by the Founders. This contradiction was a central flaw in Robert Bork's constitutional theory.

Living constitutionalists face fewer unavoidable contradictions in advocating a democracy-centric approach to constitutional law. But those who are political liberals must reckon with the fact that many of the court decisions, legal doctrines, and political institutions advocated by liberals are themselves at odds with such an approach. It's hard to argue that democracy is the central value of constitutional law, and simultaneously support decisions like Roe v. Wade, Obergefell v. Hodges, or even Brown v. Board of Education. All of these rulings - and many others like them - struck down legislation favored by democratic majorities for the (often-justified) reason that they violated individual rights that had, at most, only a very limited connection to democratic participation. While there is a non-trivial "democracy-reinforcement" justification of Brown based on the fact that African-Americans were not allowed to vote in most of the states that practiced school segregation, several key aspects of the decision are best understood as constraints on democratic majorities, not vindications of their power.

While the Constitution does empower democratic majorities in some areas, it also puts many constraints on them in order to protect individual rights, and mitigate the dangers of widespread voter ignorance and prejudice (a problem that was a major concern of many of the Founders). Countering these threats is, if anything, even more pressing in an era of resurgent demagogues exploiting political ignorance even beyond previous limits, and growing partisan bias.

To adapt Nancy MacLean's now-infamous formulation, one of the purposes of the Constitution is to weigh down democracy with some chains. But despite MacLean's badly flawed attempt to paint this idea as some kind of pernicious aberration spread by radical libertarians supposedly committed to plutocracy, this is in fact a longstanding core element of liberal constitutionalism. As Thomas Jefferson put it, writing in protest of the democratically enacted Alien and Sedition Acts, "[i]n questions of power,… let no more be heard of confidence in man, but bind him down from mischief by the chains of the Constitution." Jefferson didn't always live up to his own principles in that regard. But he was right nonetheless.

Admittedly, the term "democratic" is sometimes used as just a kind of synonym for "good" or "just," rather than in the more narrow sense of referring to governance by majoritarian political institutions. By that standard, such policies as school segregation, cruel punishments, and laws banning same-sex marriage are inherently "undemocratic," no matter how much political support they enjoy. Whatever the linguistic merits of this usage, it is not analytically helpful. If anything good is by definition also democratic and anything democratic is by definition also good, then democracy ceases to be a useful concept for constitutional theory, or any other type of intellectually serious analysis. Instead of saying that the Constitution is focused on promoting democracy, we could simply say that the purpose of the constitution is to promote good and minimize evil. That may be true, in a sense, but it provides little if any useful guidance on any specific constitutional issues.

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Provocative Nat Turner-Inspired Portraits Fuel Debate After Their Removal

Stephen Towns, “All is Vanity” (2016), acrylic oil, metal leaf on canvas, 36 x 36 inches (all images courtesy the artist and Rosenberg Gallery at Goucher College unless otherwise noted)

In 1967, author William Styron won a Pulitzer Prize for The Confessions of Nat Turner. The novel retold the story of a real historic event — the 1831 slave revolt of Southampton County, Virginia — narrated from the imagined perspective of Turner, the educated and highly religious slave who led our nation’s bloodiest slave revolt.

Although white militias ended the rebellion within a few days, the rebel slaves liberated a number of local plantations and killed between 55 and 65 white slave owners, including women and children. After two months in hiding, Turner was captured and later hanged, and his corpse was subsequently beheaded, quartered, and flayed (his body parts were auctioned off and his skin was made into collectible items). In the aftermath, approximately 120 slaves and free African Americans were murdered in the region by white militias and mobs as retribution, and southern state legislatures passed new laws prohibiting the education of slaves and restricting the civil rights of free black people in order to prevent future revolts.

As with most American history, Nat Turner’s story has been told and retold by white male authors, including Styron, with fewer known works of historical research, art, or literature about him by black authors. It is within this context that the Baltimore-based, African-American artist Stephen Towns made his own series of paintings and quilts based on Turner’s rebellion, after he received research funding from a Rubys Grant in 2015.

The Joy Cometh in the Morning series presents six painted figures, each representing a martyr from the rebellion — individuals who made a choice to wage war for their freedom for personal and spiritual reasons, knowing that their chances for success or survival were zero. In Towns’s vision, each wears a noose around their necks, held in place by one raised fist, a gesture of black power. In this pose, the artist empowers each individual to be seen as master of their own destiny, to be read as tragic heroes, and to command respect and admiration in the face of sacrifice.

On view at Goucher College’s Rosenberg Gallery in a solo show titled A Migration, the series (one of several in the show) recently provoked a complaint from an African-American employee. The artist responded by asking gallery director Laura Amussen to remove the paintings on August 20, and to replace them with taped squares on the gallery wall where each had been. This decision has inspired divisive reactions on social media that in many ways recall the debates that arose from Styron’s novel 50 years ago.

* * *

StephenTowns, “I Fear no Evil” (2016), acrylic oil, metal leaf, bristol board on panel, 12 x 12 inches

Although there is much to learn from Nat Turner’s story, it presents a tinderbox of conflicting emotions. Is it an account of bravery? Does it promote black pain? Is it a shameful story that white America would like to forget? It’s no surprise that authors and artists have found Turner to be an inspiring muse, but equally predictable that the resulting works are controversial.

Styron himself received his fair share of criticism during his lifetime. Initially, his Nat Turner novel received widespread praise; it received glowing reviews from the nation’s top newspapers, the movie rights were quickly sold to 20th Century Fox, and it won the Pulitzer. The author received acclaim from African-American audiences, in particular from his friend and colleague James Baldwin, and was given an honorary degree at Wilberforce University, a historically black college in Ohio, which he claimed was his greatest achievement, especially as a self-identifying Southerner.

However, after the summer of 1968 brought the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, and rioting ensued in cities across the US, the author’s legacy took a U-turn. Because of Confessions and the controversy it produced, Styron became a reviled and contentious literary figure for the rest of his life. Black individuals and groups protested the book for being historically inaccurate and disrespectful, full of stereotypes and cliché, and Beacon Press published William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond, a volume of essays that were initially ignored and belittled by mainstream press, but grew to build an enduring debate around issues of race within literature and art in general.

It’s worth noting that Styron’s book was based on an earlier account by another white male author, lawyer Thomas Ruffin Gray, who visited Turner in jail after his capture. He later wrote and published The Confessions of Nat Turner: The Leader of the Late Insurrection in Southampton, Virginia in 1831. This is the sole historical text that documents Turner’s story directly; it presents conflicts of interest because Gray was the attorney for others accused in participating in the revolt.

Styron based much of his novel on Gray’s account. When describing the start of the revolt, Turner claimed to have been called to action by Christ, who “had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it on and fight against the Serpent, for the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first.”

When Gray asked Turner, now imprisoned, if he found himself mistaken in enacting the revolt, he replied, “Was not Christ crucified?”

Despite his claim to martyrdom, Turner never quite achieved this celebrated status. Rather, as Towns’s story reveals, Turner has remained a controversial figure after all these years.

* * *

Stephen Towns, “The Revolt” (2016), fiber glass beads, 34.5 x 27 inches

I first encountered Towns’s Joy Cometh in the Morning series at Galerie Myrtis, in his solo show titled Take Me Away to the Stars in November 2016. The entire show was based on several years of Towns’s research on Turner, and his desire to promote awareness and healing.

The front gallery space was filled with the artist’s magnificent quilts, which imagined different vignettes from Turner’s life, humanizing him and avoiding depictions of violence. These works are powerful because of the comfort they offer through their harmonious arrangement of patterned fabric and domestic familiarity, with figures rendered as silhouettes. Each quilt allows the viewer to grow emotionally attached to it before realizing the violence and controversy, the inherent feelings of conflict and remorse that Turner’s story brings.

But the six paintings in the back gallery were a sucker punch. Unlike the quilts, the Joy Cometh series is rendered in oil paint and portrays the slave rebels in highly realistic likenesses based on Towns himself and five others who modeled for him. Each painting depicts the subject’s face at actual size and, hung at eye level, the individuals — three men and three women — return your gaze with eyes that are confrontational, sparkling with intelligence and determination.

Stephen Towns, “Shall It Declare Thy Truth” (2016), acrylic oil, metal leaf, bristol board canvas and paper on panel, 24 x 18 inches

The Joy Cometh paintings are deliberately provocative and designed to challenge commonly accepted notions of history and race in the US. They are uncomfortably realistic and they inflame your emotions, no matter what your racial or familial history. While at Galerie Myrtis, these paintings were written about in multiple Baltimore publications, and, as far as I know, attracted little controversy and were widely praised. Perhaps this has something to do with the fact that Galerie Myrtis specializes in work by African-American artists, and that the gallery’s typical audience regularly sees and consumes contemporary art.

In late August, at Goucher College’s Rosenberg Gallery, the same paintings provoked a completely different response. A Goucher employee deemed the paintings offensive, stating that she shouldn’t have to look at black faces with nooses around their necks at work, leading to a mediated discussion between the employee, the gallery director, and AU professor and artist Zoë Charlton in which the employee expressed that these paintings made her work environment feel abusive and uncomfortable.

After he was informed of the complaint, Towns issued a statement and requested that the paintings be removed, but that taped squares remain where the paintings were originally hung. It’s unclear whether the college would have insisted upon the paintings’ removal, but it was an unfortunate possibility. Rather than forcing the college’s hand, Towns chose to remove his own works.

“It has come to my attention that the work from my Joy Cometh in the Morning series has offended staff at Goucher College,” says Towns in a statement placed in the gallery alongside the empty frames. “Though I am saddened to see the work go, I value Goucher’s Black employees’ concern. The intent of my work is to examine the breadth and complexity of American history, both good and bad. It is not to fetishize Black pain, nor to diminish it.”

On social media, Towns’s preemptive actions and statement have been applauded for being sensitive and generous to the offended employee, but they have also spawned inflammatory dialogue. Nonetheless, the discussion, although uncomfortable at times, has been wide-ranging and productive.

* * *

The taped squares placed in lieu of Stephen Towns’s painting at Rosenberg Gallery, Goucher College (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Some online commenters predictably focused on Goucher College’s failure to engage in public discourse as an educational space — and the decline of college campuses in this regard (“Is Goucher now going to remove every thought provoking book in its library because someone finds the book offensive?” one person wrote on Instagram). Other discussions revolved around the role of art within society — and an institution’s responsibility to properly support productive and positive dialogue for all those who come into contact with the art on display, not just students and faculty.

Sadly, our discussion now revolves around the removal of the paintings rather than the content or merit of the paintings themselves, but this, too, appears to offer new solutions and opportunities for artists, curators, galleries, and colleges, moving forward. We can only wonder if the paintings would’ve remained if there had been, for instance, a written statement preemptively placed alongside these specific works to offer context. If more resources in the form of educational programming, discussions, or publications had been offered to college employees and the larger community, perhaps the students, faculty, and staff could’ve considered the paintings’ aesthetic value and historical content instead of blank squares and an artist’s statement.

Stephen Towns’s statement at Rosenberg Gallery, Goucher College (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

One commenter expressed on Facebook that “This is not our fight. This is about the free exchange between an individual artist and his audience. I regret the outcome, but the artist’s wishes need to and should be honored.”

This brings us back to basic questions, such as whether it is the artist’s responsibility to make the audience feel comfortable. Is it possible to exhibit provocative art and offend no one?

As history teaches us, invoking Nat Turner’s historical legacy is a divisive endeavor, but we are in dire need of diverse perspectives and interpretations of him, especially by artists of color who can attempt to translate such a contentious historic narrative into an empathetic contemporary context. Towns’s paintings are hard to look at; they successfully mirror just a fraction of the violence and terror experienced on a daily basis by thousands of Americans who were owned as slaves.

* * *

Stephen Towns, “The Righteous and the Wise, and their Works are in the Hand of God” (2016), acrylic oil, metal leaf on canvas, 40 x 30 inches

Although it was originally ridiculed in mainstream press, the slim book of essays William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond gained a national readership and inspired protest, dialogue, and controversy. The 10 authors were comprised of academics, editors, psychiatrists, and librarians, and offered numerous reasons to reject Styron’s depiction of Turner, especially his use of “myths, racial stereotypes and literary clichés even in the best intentioned and most enlightened minds,” said contributing author Mike Thelwell. “The real ‘history’ of Nat Turner, and indeed of black people, remains to be written.”

Styron’s novel spawned agonizing conversations about authorship, race, history, and art in the US, foreshadowing decades of debate and dialogue. Although it was contentious, the conversation between Styron’s Nat Turner book and the Ten Black Writers response helped to generate a new genre of fiction featuring African-American authors including Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Charles Johnson’s Middle Passage, Edward P. Jones’s Known World, Sherley Anne Williams’s Dessa Rose, and even recently Coleson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad.

“I do not believe that the right to describe… black people in American society is the private domain of Negro writers,” wrote John A. Williams in Ten Black Writers Respond. But one of the most notable consequences of this critical book of essays is that it helped to create a new space for multiple voices and hundreds of different versions of US history by historians, authors, and artists of diverse backgrounds.

At Goucher College, Towns made the decision to remove his Joy Cometh series from the gallery based on the strong reaction it inspired and his desire to promote healing rather than to inflict pain. But these paintings are powerful because they diverge radically from the comforting version of history that most Americans prefer.

Towns’s actions raise important and conflicting questions for all contemporary artists of conscience, specifically regarding the role of controversial works of art and the appropriate context for its consumption. At Goucher College, the students, faculty, and staff can no longer directly engage with Towns’s paintings. But it remains to be seen whether the work, as well as its removal, will continue to inspire a spirited dialogue that yields productive results.

Stephen Towns: A Migration continues at Goucher College’s Rosenberg Gallery (1021 Dulaney Valley Rd, Baltimore) through October 16. An artist’s receptions will be held on Tuesday, September 12 at the gallery.

The post Provocative Nat Turner-Inspired Portraits Fuel Debate After Their Removal appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2wNRSv2 via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Disability - Medical Fact or Social Construct?

Disability is a term widely used for the social condition recognised as resulting from any type of physical or mental impairment mainly identified through medical procedures. Some are present at birth while other impairments occur at various stages of an individual's life either as manifestations of genetic conditions or as the result of conflicts (e.g. war), and accidents. Examples are varying degrees of blindness, deafness, speech impairments (dumbness) and loss of limbs. Chronic illnesses too should be added to this list. Usually prosthetic devices such as magnifying glasses, Braille, hearing aids, sign language, crutches, wheelchairs and other similar aids have been designed to ameliorate handicaps in living, experienced by disabled people.

Constitution of Disabled Peoples' International (1981) defines Impairment as 'the loss or limitation of physical, mental or sensory function on a long-term or permanent basis', with Disablement defined as 'the loss or limitation of opportunities to take part in the normal life of the community on an equal level with others due to physical and social barriers'

Since all serious impairments giving rise to disability appear to stem from a recognised medical condition, historically, disability in Kingston studies relied on a medical model centred almost solely on the individual. Following the medical model the disabled were segregated from 'normal' people and seen as deficient, lacking in self-efficacy, needing care. The disabled were defined by their deficiencies, in what they could not do, and not by what they could do. Society at large made no attempt to adjust to the requirements of the disabled, to integrate them, instead tending to isolate them in institutions or at home. Impairment was seen as the problem, and the disabled were restricted to being passive receivers of medication, care, and targeted assistance through state intervention or charity. Even today, as befitting the medical model, disabled people are regarded as requiring rehabilitation. They are subject to negative stereotyping and prejudice by the rest of society. Further, the ubiquitous built environment imposes restrictions on their mobility, access to employment and recreation.

Mike Oliver (1996), an academic with first-hand experience of disability and what it entails, calls the medical model an 'individual model' making a binary distinction between it and the social models which followed the Disabled People's Movement in the 1970s. Vic Finkelstein, another academic and Paul Hunt, an activist, were also involved in helping to form the Union of the Physically Impaired against Segregation (UPIAS). Oliver fought against the 'medicalisation' of disability denying that there never was a 'medical model' of disability. Oliver believed that problems attendant on disability should not be regarded exclusively as the responsibility of the medical profession and other similar 'experts' who, from a position of power, see the problem as entirely located within the individual. For Oliver and others working in the disability field around the 1970s disability was a social state and not a medical condition. These pioneers were influenced by Marxist rhetoric much in evidence at the time.

The individual discourse on disability is allied to World Health Organisation pronouncements, as for example, by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. It owed its existence to advances in science and medicine which placed disabled individuals into medical categories for the convenience of medical practitioners and other health professionals. This, though eminently practical and appropriate at the time, was later experienced by the disabled population as an oppressive situation. They felt themselves labelled, manipulated, and powerless vis-a-vis their own bodies and personhood.

There is inherently nothing wrong with impairments being initially identified and treated as a medical condition. Indeed, this is a necessary first step, especially when individuals require continuing, lifetime medical care. It is when such treatment excludes or disregards the social environment, which to a large extent defines the parameters within which the disabled are expected to function, that problems arise. It inevitably invites social exclusion and disadvantage, segregation and stigmatisation, which is the fundamental criticism against the narrow medical model.

Still, there are apologists for the medical model of disability. They regard as questionable Mike Oliver's denial that impairment has any causal correlation with the societal notion of disability. For them this is an 'oversocialized' and overly politicized view. Although he accepts that disability is both biologically and socially caused, he places 'more significant causal weight' on the former. They recognise the sociological significance of the body, but complain hat the social model suffers from 'somatophobia' due to an over-emphasis on the social context. Other researchers are keen to emphaise that there is social oppression at play in the field of disability.

Shakespeare and Watson (2002) stress that 'embodied states are relevant to being disabled'. They believe that social model advocates 'over-egg the pudding' by stating that disability is entirely a creation of society instead of accepting that 'disability is a complex dialectic of biological, psychological, cultural and socio-political factors, which cannot be extricated' to any great extent. However, Carol Thomas (2004) is critical of anyone not recognising the importance of disabilism in their discussion of disability. She thinks they confine themselves to a 'commonplace meaning of disability' ignoring the much larger significance allied to similar concepts like racism, sexism and homophobia.

Vic Finkelstein, a pioneering academic and activist in the field of disability, himself disabled, was a refugee from apartheid South Africa where he had been in prison for five years. Having been active in the civil and human rights movement in South Africa, he was immediately sensitised to the ghetto-like experience of the disabled in the UK. He saw that they were denied participation in the mainstream social and political life of the country. One of Finkelstein's collaborators Paul Hunt, had been living in residential institutions (Cheshire Homes) from childhood and campaigned with other residents for a role in the management of such Homes. Following the medical model Cheshire Homes believed it had provided compensatory measures to meet the needs of the disabled, but disabled activists like Finkelstein and Hunt saw it as oppression of a minority by society at large.

These activists saw the medical model as the default position of the disability 'industry' staffed by care managers, social workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, clinical psychologists and doctors. Disabled persons' powerless and socially inferior position was reinforced in such circumstances, however sympathetic and dedicated these professionals were in carrying out their duties. It was only after the establishment of UPIAS that the political landscape changed. UPIAS (1976) concluded that '... it is society which disables physically impaired people. Disability is something imposed on top of our impairments by the way we are unnecessarily isolated and exclude from full participation in society. Disabled people are therefore an oppressed group in society'.

Apart from the horrors of the Holocaust which enabled doctors to experiment on disabled victims, there is at least one documented case of clinical abuse of disabled children in the USA. Referred to as the Willowbrook Experiment, in 1956 disabled children were deliberately infected with viral hepatitis to monitor progress of the disease over a lengthy period of 14 years. Parents had been under pressure to accede to it. It was also approved by the New York State Department of Mental Hygiene. To a large extent such extreme measures are no longer evident, but one can see how disability had been a custodial discourse.

A good example of a drastic change in the medical model is that only about four decades ago, the universally acclaimed and used Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) listed homosexuality as a mental illness. Psychiatrists and clinical psychologists practised aversion therapy (among others) to 'cure' these 'unfortunates'. In spite of objections from a few extreme right politicians and religious fanatics, it is now accepted as a normal and positive variation of human sexuality. Indeed equal opportunity and human rights legislation have recognised the 'gay' community as a minority group. Some states even allow civil union and even marriage between same sex couples.

How the society's views and treatment of the disabled have changed over the years is demonstrated by the example of Lord Nelson and President Roosevelt. With an arm amputated and blind in one eye, 'the statue of Horatio Nelson defies modern infatuation with physical perfection by flouting his impairments.' He contrasts Admiral Nelson with the wheel-chair using wartime US president Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Unlike Nelson, he was born into a modern culture where having an 'impairment' was supposed to directly 'disable' a person. Therefore, a 'public statue of Roosevelt sitting in a wheel chair was unthinkable' So now we are presented with a statue to a major USA public figure that takes care to hide any evidence of his impairment. There may not be a call to erect a statue to an even more modern celebrity like Prof. Stephen Hawking, but one must grant that without the medical advances that recognise his impairments making it possible for him to receive the right medical treatment and continue living and working as he does, there would not be a social or academic role for him to fill with such distinction.

In Australia, a variation of the social model was referred to as the rights-based model of disability. As in the UK, disabled people as a group there sought a political voice. Such activism and advocacy has brought gains, but they admit that there are also limitations. Although as a political strategy it helped to bring about needed changes through legislation, it locks people into an identity defined as being members of a minority community. This way the conceptual barrier between 'normal' and 'abnormal' is maintained. There are also new challenges when the latest genetic and reproductive technologies include a larger proportion of the population as carriers of 'bad' genes and unwittingly placed in the disabled category inviting discrimination and avoidance.

Four decades after the Cheshire Homes incident, we now have the spectre of Remploy Ltd. a government owned factory network across the UK established in 1945 offering both employment, and employment placement services, to the disabled, being dismantled. Remploy had been producing or assembling a vast range of products in its 54 factories spread across the country. Towards the end of the last century it even moved into service sector work. In 2009/10 Remploy placed 10,500 disabled people in jobs in a range of sectors. This year the Coalition government has decided to close 36 Remploy factories making 1700 workers redundant (press reports). It is unlikely that UPIAS would accuse Remploy as being in the business of segregating the disabled, but at some early point in a disabled person's life that type of provision was always likely to have been necessary.