#this especially is about people with special interests in quote unquote mundane things that we see every day

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

having a partner with a special interest in something that you don't already is so beautiful and for lack of a better word Special because it also becomes your special interest by extension. You think of them every time you see the subject of their interests - An old train, a particularly shiny rock, a wild mushroom - and you can't help but smile.

You take pictures of these things, you put them in your pockets, you hoard them to show your partner so you can hear their wonderful voice prattle on endlessly about their passions. Their knowledge sticks with you. You find yourself thinking stuff like "This is a snowflake obsidian with a maybe Potassium inclusion. My partner told me this one"

I'm bad at words but like. love & knowledge & autism ok? autistic love is beautiful. Take some time to go to Wikipedia today

#puppibarks#this especially is about people with special interests in quote unquote mundane things that we see every day#it breathes love and life into these otherwise dull objects that we would otherwise discard#its probably obvious from the post but yes i am dating someone with a special interest in geology aka Fuckin Rocks#btw babe if youre reading this. mwah. love you#<- THAT KISS IS FOR MY BOYFRIEND ONLY!!!! you cant have it. look yhe fuck away

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ahistorical, Absurd, and Unsustainable (Part Three)

An Examination of the Mass Arrest of the Paranormal Liberation Front

Introduction and Part One Part Two

PART THREE: Ethical Problems

Law Enforcement Conduct

The first thing that jumps out—the thing everyone talks about first and foremost about the raid—was Hawks’ murder of Twice. Murder is a controversial word in this context, I know, but I stand by it: regardless of his guilt or his intent, Bubaigawara Jin was a fleeing man who Hawks made a cold, rational decision to quite literally stab in the back. In that moment, Hawks appointed himself as an executioner of the state and murdered a man without due process—no trial, no judge, no nothing. It was an extrajudicial killing,[26] and while I know many people in the U.S. have gotten kind of jaded about that sort of thing, let me assure you that police brutality is still police brutality even when it’s being exercised against people who have committed crimes.

To illustrate this, allow me to share a few more excerpts from the Penal Code:

Assault and Cruelty by Specialized Public Employees: When a person performing or assisting in judicial, prosecutorial or police duties commits, in the performance of their duties, an act of assault or physical or mental cruelty upon the accused, suspect or any other person, imprisonment or imprisonment without work for not more than 7 years is imposed.

Abuse of Authority Causing Death or Injury by Specialized Public Employees: A person who commits a crime prescribed under the preceding Article and thereby causes the death or injury of another person is dealt with by the punishment for the crimes of injury or the punishment prescribed in the preceding Article, whichever is severer.

The punishments for Criminal Injury are imprisonment for not more than fifteen years or a fine of not more than 500,000 yen or, if the injury results in death, imprisonment for not less than three years. That’s really what Hawks ought to be looking at for Twice's murder, save that apparently heroes just aren't liable for this stuff, otherwise they'd be up against it all the time in the course of “fighting villains.” Certainly, Hawks doesn’t seem to have faced any repercussions thus far, beyond having to apologize in a press conference.

Now, again, many American readers of My Hero Academia are deeply embedded in a culture that normalizes police violence, and so there is a lot of callous handwaving about how Hawks did the right thing because Jin was a significant threat. In response to such dismissal, let me provide a few more numbers:

In the U.S. in 2019, law enforcement killed over a thousand people.

In the same year in Japan, law enforcement killed two. Two people.

In the U.S., a major factor in how police keep skating on these deaths is the legal doctrine of qualified immunity, which is nominally intended to protect officers from frivolous lawsuits in cases where they’re ruled to be acting in “good faith,” a vague ruling which has made successful prosecution of police brutality and negligence all but impossible.

Japan, and I cannot stress this enough, does not have this doctrine. The significance of law enforcement taking a life is not so casually brushed aside in other places in the world, so please don’t try to tell me that Horikoshi was trying to get across the idea that Hawks did the right thing, easy as that. The critical depiction of heroes and Hero Society dehumanizing their enemies is all over the manga.

When the Tartarus guards discuss what the government is doing about Gigantomachia, one of them complains that the higher-ups can’t use missiles—missiles!—on him because he’s quote-unquote-human.[27] During their battle at Kamino, All Might tells All For One that this time, he’s going to put him in a prison cell—he characterizes his attempt to kill All For One six years ago as a mistake. Even in the spin-off manga, Vigilantes, designated police representative Tsukauchi[28] looks absolutely aghast at Endeavor’s willingness to use lethal force against Pop Step, an innocent-until-proven-guilty minor, even though, at that time, they have all the evidence in the world that she is actively engaged in setting off bombs in populated areas.

Most prominent is the series’ treatment of the High End Noumu. The heroes rationalize them as corpses, monsters, inhuman, all in order to kill them guilt-free,[29] and this rationalization spills over to Shigaraki during the War Arc, as the chasm of understanding between heroes and villains reaches its most stark. Yet, that same arc was proceeded by the reveal of the truth about Kurogiri, which had Tsukauchi directly acknowledge that they may have misunderstood the Noumu as the series dangled the possibility that Kurogiri possesses lingering awareness from Shirakumo Oboro. Earlier, we had Ending, a man who wanted Endeavor to kill him and thought Endeavor would do it specifically because Endeavor killed the High End, and this act set him decisively apart from the non-murdery heroic norm. Even into the War Arc itself, we were getting new information on the Noumu: to wit, we were shown incontrovertible proof—in the form of Woman’s internal monologue in Chapter 268—that the High End Noumu do think.

Even if we assume the government has relaxed its prohibitions about public servants assaulting people in the course of carrying out their duty, it does not follow that Hawks’ extrajudicial execution was totally fine. Heroes are not supposed to kill because police are not supposed to kill, and in Japan, it isn’t assumed that they will the moment they run into resistance.

And look, this is not to say that Japanese police never get away with police brutality. Obviously, the country has its own problems with the issue, typically involving racism and ethnocentrism. But the way that some people in the fandom just brush off Jin’s death does a disservice to the way the series frames Hawks’ actions and what that framing is communicating to a Japanese reader.

Also, even putting aside the matter of his death, openly taunting a mentally ill man about how easy it was to fool him definitely pings me as an act of mental cruelty, though of course there’s no one to sue Hawks over that one, seeing as he murdered the victim and only witness. (Chapter 264)

That all said, there are other issues with the heroes’ actions during the raid. One is called out right in the text: Midnight acknowledges that the use of chemical agents is illegal, but calls upon Momo to engineer knock-out drugs to use against Gigantomachia anyway. Is that an action Momo will face any repercussions for at all? And if not, what does it imply about the setting that she won’t?

Here’s another big one: what’s the legality of heroes using their quirks against civilians? Because that’s what the vast majority of the PLF are, civilians. Oh, they’re suspects, sure, but throughout the manga, “heroes” aren’t set up as people who just fight any and every tiny crime they come across. From the very first chapter, heroes are set up as a specific counter to “evildoers” designated as “villains”—legally defined as people who use their quirks illegally two or more times.[30]

There is a very illuminating scene in the second chapter of Vigilantes in which Aizawa confronts Knuckleduster for his assault of a random businessman and, the moment he realizes Knuckleduster is quirkless, apologizes for the misunderstanding and walks away. If Knuckleduster doesn’t have a quirk, Knuckleduster by definition cannot be a villain, and thus, Aizawa is not authorized to throw down with him.[31] It’s somewhat unclear, not least because a lot of the evidence is in the more-interested-in-systemic-worldbuilding Vigilantes, but there is reason to believe that heroes are not allowed to use their quirks against people who are committing mundane crimes.[32] If anything, I should think that heroes only using their quirks on people who are using their quirks illegally is part of the philosophical scaffolding that gives heroes their moral authority—you see this argument from the first bearer of One For All, who loudly espouses that people not only should not use their quirks selfishly, but that quirks should only be used to help others. This kind of supposed selflessness is what MHA’s current society is built on.

To see the relevance here, consider Trumpet. Oh, he absolutely was using his quirk illegally, but can the system prove that?[33] After all, he only ever used it on allies—do you think they're in a big hurry to snitch on him? Do you think Mr. Compress is going to? And if the police can't prove Trumpet used his quirk illegally, then is he even a capital-V Villain? What about all those other rank and file types? Certainly we saw the ones at the villa fighting back with quirks, but what about those supporters at bases scattered around the country? Did they fight back, and if so, did they do it with quirks? If not, was it legal for them to be targeted by heroes?

More importantly, can they mount an argument on that, be it a legal or a moral one?

The Scope of the Operation

The next big ethical problem actually predates the raid itself, and it’s this: how did the Commission know where to target their raids? How did they obtain that information? Specifically, how many privacy violations were involved? It strains credulity well past my personal breaking point to imagine that Hawks and the Commission were able to get every name, every base of operations, especially given the limitations they were under—the fact that Hawks couldn’t communicate openly, the hard time limit before the PLF put their plan in motion, making sure they didn’t tip off someone in the massive secret organization that had people working in heroics, the government, the infrastructure, etc.—but let’s consider the sorts of avenues the HPSC did have available to them.

So to start with, they send in Hawks, who’s specifically trained to extract information from people without raising suspicion about his motives. Doubtlessly, he’s able to get all sorts of names,[34] starting with the higher-ups—not just Re-Destro and his inner circle, but also any of the advisors that e.g. run businesses that they invite him to patronize, MLA heroes, and so on. And with a decent crop of names in hand—let us assume for the sake of argument that Hawks had some way to communicate those names to his handlers—the HPSC can start doing background checks and digging in.

Where do these people come from? Where were they born, and, if they moved, where did they settle? Where do they work? What are their social pastimes? Trace the commonalities, look into publicly available records, use wiretaps…

Yes, the police in Japan can totally use wiretaps if they suspect organized criminal activity—it was one of the powers expanded significantly under that controversial 2017 law I footnoted earlier. One thing to note is that this does require a warrant, or at least the expectation that a judge will grant a warrant.[35] But how far does that go? Can they get a warrant for financial records? How about phone records? E-mail accounts?

Can they wiretap people for no reason save their association with a name Hawks provided? If a PLF member attends a Jazzercize class on Thursday mornings, does every member of that class start noticing a weird little reverb on their phone calls for a week? Does Re-Destro’s hometown have an influx of people poking around evaluating its potential as a place to live? If Slidin’ Go once snatched your dog out of traffic and you subsequently bought a Slidin’ Go keychain, are you and your family now under investigation?

Getting details on people like the CEO of Detnerat and the head of the Hearts & Minds Party is probably pretty straightforward; heck, investigating Kizuki Chitose’s publication history was probably a goldmine in and of itself. That sort of surveillance gets more complicated and difficult to justify—and to make credible to the reader—the further down the chain of command you go, though. Sooner or later, the HPSC would have had to make a call: knowing that they don’t have the time, freedom, and resources to perfectly get only and exactly everyone that’s a real threat, do they overcompensate or do they undercompensate?

You only have to look at Hero Society to know which answer they were going to go with.[36]

To be fair, undercompensating, while it clearly would have been easier on their strained resources, ran the risk of leaving threats out there to come back to bite them later. They likely thought that they’d done enough undercompensating for Shigaraki Tomura, compounded by the fact that apparently there hadn’t been enough done about Destro’s followers back in the day, either. I mean, better to grab everyone and then let the courts sort it out, right? Rather than risk innocents getting hurt?

Well, let’s talk about innocents. Innocents, and the costs of overcompensating.

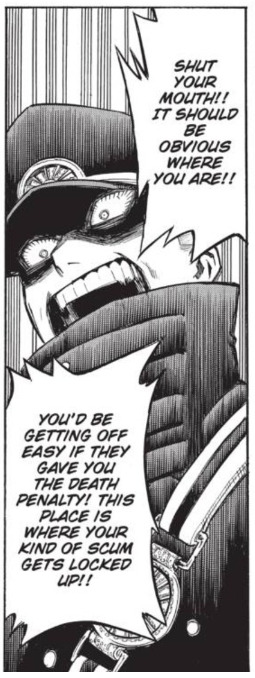

Pictured: a man who was in daily close contact with the leader of the movement and who was at one point in time in possession of a copy of the movement's manifesto. (Chapter 218)

The problem with grabbing everyone in a group, even the most obviously PLF-aligned groups, is that there are always going to be both people who don’t seem to know anything because they’re very good at living double lives and aren’t particularly active on the recruitment front, and people who don’t seem to know anything because they legitimately don’t know anything.

The Gunga Villa is straightforward enough—on paper, it was probably reserved for a business retreat for four months, because you certainly wouldn’t want some random newlywed couple booked for a nice mountain honeymoon recognizing Shigaraki Tomura wandering around. Same story for the employees; the MLA wouldn’t have put the League up at the villa if there was a chance that anyone there would rat them out. So I think we can assume relatively fairly that anyone in the building the day of the conference is solidly implicated, whatever their claims might be otherwise.

Of course, plenty might well try to claim that they were just there for the vacation, or just started work last week and had no idea the place was a nest for conspiracy, but that was where Hawks spent most of his time, and most of the people at the villa presumably fought back against the heroes. It might be a complicated process, matching hero eyewitness testimony to every person there, but you can at least sort of see the path to it.

Other groups, however, are a lot less straightforward. Consider the following categories:

The Liberated Districts

As I discussed earlier, Deika was presumably a high watermark on societal saturation, but Deika still only counted 90% of the population as “Liberation Warriors, lying in wait.” That leaves 10% unaccounted for. So who are those 10%? Are they children?[37] Some children too young to know anything about the PLF, and some old enough to know but not yet old enough to be considered warriors for the cause? Are they instead elderly people, maybe remnants from when the MLA first started to infiltrate the town that have just never had enough close family or social life to get pulled into the Liberation Army by the usual vectors?

By far the worst option is if Trumpet’s 90% accounts for anyone even remotely connected to the MLA—that would mean one out of every ten people in Deika is legitimately completely ignorant of what the powers that be had brought in. How on earth are you supposed to tell those people apart from the other 90% when the heroes sweep in and arrest absolutely everyone? Or are we to believe that the HPSC had time to get in an agent to flash a covert L-sign at everyone in town and they only arrested people who visibly acknowledged it?

These problems only get worse for our hypothetical town that’s 70% PLF. That opens you up to far more people who have only recently started getting drawn in. Consider the disaffected twenty-something whose family has no idea what’s been keeping him out so late in the evenings. The young mother who met the nicest and most convincing people via the daycare, but whose husband is always out of town on business trips so she hasn’t had time to introduce him to anyone. The working parents who just joined up and whose kid, away at hero school, doesn’t know anything—yet.[38]

Evaluating these peoples’ social circles and financial history for other PLF attachments is going to turn up a ludicrous number of false positives unless the Commission can narrow down exactly when and where such people crossed paths with the ideology of Liberation. So many people would have been raised to it, people whose entire lives are suspect, but mistaking even one new recruit for a lifelong loyalist gives you exponentially more avenues to baselessly suspect people—and as established, the Commission just doesn’t have the time to be overly discerning.

Detnerat, Shoowaysha, and Feel Good Inc.

This is another line of attack that seems like it should be a bullseye, but is actually quite the opposite. Detnerat is a business that is run by the leader of the entire movement, yet the fact that not everyone who works there is a member of the MLA is one of the very first things we find out about them! Miyashita was something akin to a personal aide or secretary to Rikiya, someone Rikiya liked well enough that he was on the verge of introducing Miyashita to his other friends—and Miyashita didn’t know the first thing about his boss’s true affiliations. It’s patently obvious from that alone that not everyone at Detnerat is PLF, and it's likely that the numbers of the faithful are even thinner at Curious and Skeptic's outfits, where they're high-ranked executives but, crucially, not actually in charge.

This is, of course, complicated further by the fact that people who work at e.g. a publishing house are probably there because they agree with that publishing house’s politics, whether or not they know what’s going on behind the scenes. Ditto with Detnerat—certainly there would be people there who just needed a job and could charm their way through an interview without an inner passion for the work, but loads of people probably work there because they legitimately believe in the company’s ethos. So how do you tell people who have relatively radical personal politics without having any idea about the terrorism apart from the people who are absolutely PLF/ex-MLA but who are now lying about it because their organization's cover is blown and the response to that is, “Well, time to go back underground!”

The Hearts & Minds Party

Membership of this party would seem to be a good indicator, but using it that way too unquestioningly is also very flawed. This is because the HMP particularly is probably an excellent recruitment tool for the MLA/PLF. The note above about having radical political beliefs but still being ignorant about the planned acts of terror is especially true for the HMP. The Commission cannot just pull the voting records and arrest all of them because plenty of them are going to be totally ignorant of what was really going on with the heart of the party, only joining up because they believed in the kinds of things the HMP was platforming on—less repressive quirk use laws, prison reform, very possibly issues like the abolishment of the legal category “villain” or greater social safety nets. Just because someone votes for those things, doesn’t mean they know about or would support the MLA’s violent extremism or the PLF’s anarchic goals.

So at what level of initiation does the Commission call a cut-off? How long does someone have to have been voting straight-ticket HMP for them to be considered condemned by that association?

Over and over again, the question arises: how did the heroes and the police distinguish the initiated from the uninitiated? And given that Japan’s legal system at least nominally requires that guilt be proven, what are they going to do when huge numbers of those people claim innocence?

The Presupposition of Guilt

Let’s take a few minutes to circle back to what I talked about earlier, the presumption of guilt and how it relates to arrests, convictions, and the perception of arrestees in Japan. This is going to swerve hard back towards real-life Japan issues for a bit, but it is exceptionally relevant when examining what’s likely to happen to the people arrested in the raids, innocent and guilty alike, so thanks in advance for bearing with me.

In Japan, the rate of conviction is extraordinarily high—if you’re in anime fandom and active in social justice circles, you may have seen the tumblr posts about the country’s famed 99.9% conviction rate.[39] There are a range of explanations for this. Defenders argue that, compared to police in many other countries, police in Japan are very cautious and don't move to prosecute unless a case is all but airtight; thus, many who are arrested may well be released without charge if there is even the slightest doubt that the case will hold up in court. One can easily see truth to this by looking at the numbers on how many people are arrested in Japan versus how many are actually charged: Wikipedia notes (albeit without citation) that in the U.S., roughly 42% of arrests in felony cases result in prosecution, while in Japan the figure is only 17.5%.

Conversely, critics note that a major feature of convictions in Japan is the confession, and confessions can be coerced, particularly in the sorts of conditions that those imprisoned in pre-trial detention are kept—no legal representation, no contact with their families, loved ones or employers, no requirement that they be informed about what they’re being charged with, potential weeks upon weeks kept in isolation, sessions of questioning that can extend for most of the day.

There have also been cases in which confessions have been found to be falsified, for example by having the suspect sign a paper and then filling in or altering other details after the fact.

There are some other factors about confessions to be aware of here:

In Japan, it is not legally permissible for a suspect to be convicted solely based on their confession. The constitutional provision in this regard is something called himitsu no bakuro, the “revelation of secret.” The revelation of secret is something in the confession that is factually verifiable and which, at the time of the confession, only the suspect could have known. Common examples are things like the location of a previously undiscovered body or the time and location where a weapon used in the crime was purchased. The majority of verdicts that are overturned in Japan are overturned because of issues with a confession.

Sentencing is also very lenient compared to the U.S., particularly if the suspect was cooperative with police and admitted guilt (seen as showing remorse). Thus you wind up with a situation in which suspects believe that they’ll lose a case if they go to trial (because practically everyone does) and prosecutors—rather more aware of the weaknesses in a case than a confused and vulnerable layman—don’t want to bring a shaky case to trial, and thus both parties are invested in whatever will get the suspect out with a minimum of effort. The result of this is a high number of people released on “suspended prosecution,” which is an admission of guilt, but with a prosecutor's decision to show lenience while still establishing precedent for possible later offenses warranting more severe punishment. This is a particularly common result for first-time offenders, especially in non-violent crimes.

Note that suspended prosecution is not at all the same thing as being released for lack of evidence; a suspect is conceding their guilt by accepting the arrangement. However, many suspects who the police might not be confident in convicting are known to sign confessions and accept the arrangement regardless, because, along with fear for their livelihoods, it’s known that judges tend to view extended time in detention as a sign of guilt. Also too, if admitting guilt is seen as showing remorse, then maintaining one’s innocence is often perceived as a lack of remorse—leading to fears that fighting the charges will result not only in defeat, but also in harsher sentencing!

All of these factors combine into a problem with perception of guilt that feeds on itself endlessly at all levels. Let me use a run-on sentence to summarize: the general public views anyone who is even arrested as probably guilty, because the police are seen as generally only moving on those who are guilty, because police specifically only prosecute those who they can all but prove are guilty, but guilt can be “proven” by a sufficiently detailed confession, and while confessions are required to have some corroborating evidence, they can easily be falsified and may well be offered up with minimal resistance because the suspect is also convinced that judges will only be harsher on them if they put up a fight because suspects also believe that they will be convicted at trial because everyone knows the conviction rate is unbelievably high.

Japan likes to think of itself as a “safe” country, which is in large part why its deeply concerning arrest and detainment procedures have held up repeatedly in court. These things help keep people safe, after all, and who wouldn't want people to be safe?

Returning, then, to the matter of My Hero Academia and the Paranormal Liberation Front mass arrest, I don’t think it’s overstating things to claim that the dehumanization of villains and the glamorization of heroes has probably exacerbated these problems.

Cruel punishments are illegal under Article 36 of the Japanese constitution? But what if someone really, really deserves it, though? (Chapter 94)

You can see that willingness to shrug off civil rights violations as long as it means safety in the symbol All Might represents, a hero who is there to beat up baddies, not ask questions about why they're being bad. Ditto Tartarus, where the Bad People get put, regardless of whether their Bad really warrants so awful a punishment or whether the severity of such a punishment serves as an effective deterrent.[40]

As to the presupposition of guilt, if a hero thinks they saw someone Doing A Bad, and confidently testifies to that effect, who’s going to doubt them? It’s blunt to the point of headache-inducing that Midoriya Izuku, the boy who will be the greatest hero, who’s treated by the story as if he’s the first person in history to think about “saving” a “villain,” doesn’t even start to think about such a thing until he literally experiences a psychic impression of a five-year-old crying within the heart of Shigaraki Tomura.

At the press conference in Chapter 306, it’s illustrated numerous times that huge portions of society don’t particularly care about Dabi’s accusations. They don’t ask for Hawks to face justice for the murder he openly admits to committing; they don’t ask for apologies for the heroes’ wrongdoings. They ask for heroes to make them feel safe. Even if it means lying to them; even if it means asking Endeavor to go out there and “take down” his firstborn son. People are uneasy about the accusations, certainly, but what they want is not for heroes to take responsibility for their actions, to atone for them, but rather to deny that there’s any truth to the accusations at all.

This is not a society that, in the wake of Gigantomachia’s rampage, is going to be open to the possibility that some people caught up in the mass arrest are legitimately innocent and that everyone, even villains, deserves to be afforded the full extent of their rights.

The Dissolution of the HMP

Speaking of rights, let’s go over one that we can immediately see has been flagrantly violated in the manga compared to the state of real-life Japanese law—the overnight dissolution of the Hearts & Minds Party.

As discussed earlier, it's unlikely that every member is a dyed-in-the-wool terrorist. There are bound to be perfectly innocent people in the country who just so happen to agree with the HMP’s campaign platforms. Now, all of those people are going to turn on the evening news[41] and be blindsided with the news that their political party has just been dissolved and some enormous percentage of its membership arrested. This was not publicized or forewarned; it just happened, in a matter of hours. Do you think those people—people who are members of a party that specifically opposes the current status quo—are just going to nod and say, “Oh, wow, that sucks, but who am I to question the wisdom of the government and its agents? Time to find a new political party, I guess!” Would you?

I can assure you that you wouldn’t, because let me be clear: under current Japanese law, what we’re told happened to the HMP is unbelievably illegal—not only because they were dissolved at all, but particularly the speed with which that dissolution was carried out.

I mentioned earlier, in the section “Japan and Illegal Organizations,” that there were methods by which organizations can be dissolved. Now I’d like to look at that in more detail.

Any organization that’s been flagged as a potential threat—that “terroristic subversive activity” designation—can come under investigation from the Public Security Intelligence Agency. Their recommendations are then passed up for evaluation by a member of the Public Security Examination Commission,[42] who can pass a variety of prohibitions—the bans I mentioned earlier on printing activities, public assembly, and a few others. These prohibitions are issued in periods lasting up to six months, at which point they are re-evaluated and can be dismissed or renewed.

If the Public Security Examination Commission decides that the comparatively soft-pedal restrictions on freedom of the press or freedom of assembly are not sufficient to deter the organization in question from committing terroristic subversive activity continuously/repeatedly in the future, the Commission can elect to order the organization dissolved. This revokes their rights mentioned above entirely, and further stipulates that they liquidate their assets,[42] and that no member of or representative for the organization can take actions in the organization’s interest (e.g. things like opening bank accounts or buying property). The only exception to the latter restriction is a designated representative for the organization who is granted the right to manage its assets in the process of overseeing the dissolution.

Any of the designations above can be appealed, but dissolution is permanent until specifically overturned.

Now, it might well seem that the HMP could be targeted under the “advocating for subversive terroristic activity” criteria, but here’s the problem with that: that criteria is based on the organization engaging in/advocating for such terroristic subversiveness as an organizational activity—that is, the activity in question is a foundational, core aspect of the organization’s endeavors. And I simply don’t think that’s how the HMP operates. To reiterate, I believe they’re a recruitment tool, meant to siphon people into the MLA (later the PLF) proper, but otherwise a perfectly legitimate political party with real political aims, outreach, goals, and so on.

Of course, I can easily see the anger over all the destruction leading the Ministry of Justice to being heavy-handed in its response to the Paranormal Liberation Front and any organization even suspected of being associated with it, of which the HMP is the most prominent. I could also simply be wrong about what the HMP says at their rallies. Regardless of either of those possibilities, however, there is still the matter of the timetable.

There was a period in Japanese history that organizations—political parties especially—could be dissolved on the spot. The Meiji Constitution granted that right to the Minister of Home Affairs, a Cabinet position appointed by the Emperor, and indeed, any number of socialist, communist, or labor-oriented parties were banned and dissolved within scant months of their establishment for their alleged leftist or subversive leanings.[44] The Farmer-Labor Party of 1925 was dissolved three hours after its establishment! So clearly there’s some precedent—or at least, there was. Like many things, the power to summarily dissolve organizations did not survive the Meiji Constitution’s transformation into its modern-day incarnation after World War II.

The Subversive Activities Prevention Act, the same one that lays out the causes for dissolving an organization, also details a legally mandated process by which this dissolution is carried out. Most prominently, organizations cannot just be dissolved with no notice, no chance to defend themselves. Any disposition curtailing an organization's activities, from the bans on their printed material to complete dissolution, is required to be announced both via the government's official gazette[45] and, if the residence of a chief officer or representative of the organization is known, also via written notification. These notifications must be sent at least seven days before the hearing date—a hearing which, further, the organization has the legal right to send agents to in order to present statements and evidence in their own favor, as well as examine the evidence being presented against them.

This clearly did not happen. Bare minimum, Hanabata Koku, as leader of the Hearts & Minds Party, should have had an address the Commission could get ahold of, especially given all the snooping they so obviously must have been doing to unearth the extent of the PLF’s reach.

It’s instructive, in this regard, to look to history. To wit, I’ve said a lot about how gun-shy Japan is to dissolve organizations outright, thanks to its history of governmental repression—but how true is that really? If the government really wanted to, couldn’t it just decide to crack down on something and ride out the controversy? Has it done as much before?

To put all this into proper perspective: no. It hasn’t. The government has invoked the Subversive Activities Prevention Act against a group rather than individuals only once in all the time since the act was passed in 1952.

It was against Aum Shinrikyo, and it didn’t happen until seven months after the subway attacks. Even with nearly unanimous desire to prosecute, even though Aum had been under police surveillance prior to the attacks, even though lawsuits against them were and had been ongoing, meaning at least some measure of investigation was being done openly, it still took seven months to gather the evidence, submit it to the Public Safety Examination Commission, allow Aum their appeal, and enact the ruling. That’s because, in a society ordered by democratic processes, these things take time.[46]

But the HMP? No one who wasn’t a member knew about their affiliation with the League of Villains—much less an underground army!—until Hawks got the word out, and the Hero Public Safety Commission had to be rigorously careful that news of their investigations not leak because they knew they had their own moles to deal with. So far as we know, the Hearts & Minds Party remained a legit organization right up until the day of the raid. It is functionally impossible under current Japanese law for them to have been dissolved in the scant few hours between the commencement of the raid and the attack on Tartarus in which the two guards mention the dissolution.

Even if the relevant agency in the Ministry of Justice submitted their paperwork the absolute minimum of time in advance, there is no way the HMP and Trumpet—and therefore Re-Destro and the League and everyone else—shouldn’t have known that the government was moving against them. The only answer is that the Ministry of Justice was evading its legal obligation to notify both the public[47] and the HMP itself, or that the Japanese government, in the wake of the Advent of the Exceptional, throttled back on constitutionally guaranteed freedoms exactly the way human rights activists today are always warning about.

Stigma and Recidivism

In the same way that In Custody is not (or shouldn't be) a magic status effect preventing villains from escaping from police, In Jail is not an endgame state. Most people in prison are not there for life (or death) sentences, particularly not in Japan. Even if the majority of the PLF gets stuck in prison for decades, there will, eventually, be an “after” for them. So what happens “after”?

Well, like many countries, Japan has made efforts in the modern day to offer training classes and parole officers to help reacclimate ex-convicts into society once they’ve done their time, but it remains a difficult process, and the country has a relatively high recidivism rate. Given the stigma against criminals—present to a degree in all countries, but particularly exacerbated in Japan—it is frequently difficult for released prisoners to find stable housing or employment—both key factors helping to prevent recidivism.

So does MHA’s Japan have similar programs? Well, it’s hard to say, given that the only prison we’ve actually seen is Tartarus, which is obviously a poor model to base a lot of judgement on—save, of course, that any country that could develop a place like Tartarus is a country with an appalling deficit of care for criminals’ human rights, which doesn’t bode well for their other prisons.

Speaking of things that don’t bode well, though, we have two obvious examples in the canon of how convicted criminals fare: both Gentle Criminal and Twice are, it’s suggested, prosecuted for their foundational fuck-ups—Tobita for obstructing public duties[48] and Jin for his traffic infraction. It’s unclear whether they went to prison or not—given the relative lenience shown to first-time offenders, I’m inclined to think probably not—but even given these very mild offenses, their lives were turned completely upside-down, and no apparent efforts were made to help them through chaotic periods that saw Tobita apparently disowned and Jin losing his job.

Consider the harsh reactions they garnered and the apparent lack of assistance from any social structure despite the relative mildness of their wrongs, and things start to look very bad indeed for the PLF. Will there be any steps taken at all to deradicalize them? Does taking such steps seem likely, given what we've seen of MHA’s legal and carceral systems thus far? Further, if there is no plan for deradicalization, how exactly do the heroes propose to stop this from happening again (and again, and again and again and again)?

Here’s another alarming thought: what will be done with the children? There’s no way around the fact that the MLA, and therefore the PLF, included children[49]—and I don’t mean it in the tumblr sense of describing a sixteen-year-old as “a literal child,” though there would be some of those, too. No, I mean the grade-schoolers, the toddlers, the babies. Maybe some of them will have non-PLF family they could hypothetically go to, but as I have written about in the past, there’s a very real bias about orphans and other children separated from their parents in Japan, and even blood ties are not always enough to overcome that stigma. Alternative care is in a woefully sorry state as it is in Japan, and this would only be compounded for PLF kids—damned first for their criminal associations and again for being the children society doesn’t want.

However many thousands of them that may be.[50]

So here again, a question recurs. Where before it was, “How do you tell the guilty from the innocent?” here it’s, “How do you stop the societal backlash from ruining countless peoples’ lives both now and for decades into the future?” What kind of stigma will all these people—rank and file who come out of prison deradicalized and ready to rejoin society, children who were too young to understand why heroes took their parents away, ignorant family and friends who just lost loved ones to a massive government sweep, innocents swept up in the net and imprisoned for crimes they didn't commit—going to be facing? How long, then, before that stigma sees them radicalized in turn?

You cannot sweep 115,000 people under the rug and not expect there to be a stain—and given the narrative themes of the rest of My Hero Academia thus far, it’s absurd to think that’s even an option.

Next time: how scrapping the ex-MLA portions of the PLF undermines MHA's narrative integrity.

-----------------------------------------------------

Footnotes (Part Three)

[26] And in the legal sense, murder in the second degree.

[27] For the monstrous callousness of his comments in that conversation, said guard is immediately murdered by karma All For One. I very much hope we ever get Shishikura’s opinion on this, because I’m pretty sure the guard was his dad.

[28] Who, in Chapter 35 of that series, leads a group of police firing rubber bullets at an active villain, emphasizing that the police are trained in non-lethal tactics, and any escalation from that is not to be taken lightly.

[29] Indeed, you could make a fair argument that that’s exactly why the manga included the Noumu to begin with, though the lower-tier ones wind up captured as often as not.

[30] Vigilantes, Chapter 74.

[31] This sidesteps the matter of “rescue heroes,” those who focus on disaster response and evacuation. Note, however, that this is not a categorization that pits those heroes against non-quirk-abusing civilians. Non-quirk-abusing civilians are criminals for police to deal with, not heroes of any stripe.

[32] This would be in keeping with real-world de-escalation tactics. So for e.g. the purse-snatcher in Chapter 1, where we’re told he didn’t use his quirk until he’d been backed into a corner, I would bet that Kamuy Woods or whoever confronted the thief didn’t start actually using their quirk on the man until he went into giant mode. That is anyway a kinder interpretation than noting that he was a heteromorph and would have been using his quirk automatically just by virtue of existing in public.

[33] After digging him out from under the stairway it had a teenager drop on top of him, I mean. Did he even have much of a chance to use Incite at the villa, do you think?

[34] Though given that literally every member of the MLA we’ve met is addressed solely by their code name, I don’t for a second believe he could have gotten real names out of everyone he talked to.

[35] And judges virtually always grant warrants. It’s that presumption of guilt thing again.

[36] But that panel of the normally taciturn Edgeshot shouting at a bunch of high schoolers not to let a single person escape is pretty damn telling too.

[37] 14% of the Japanese populace is under 14 years old, so that’s not too far off, though I’d be inclined to think, based on everything we know about them, that the MLA was having more kids than Japan at large, not fewer.

[38] This should have been Uraraka, by the way.

[39] An exaggeration, but only by a handful of tenths of a percentage point.

[40] Though until recently, it’s served as a great check on recidivism, clearly.

[41] You know, assuming that they weren't all arrested in the middle of their workday or cleaning house or going to university or what have you.

[42] Both are among the agencies that make up the Ministry of Justice. I’d be willing to bet that, in-universe, the Hero Public Safety Commission is also under the Ministry of Justice umbrella.

[43] The funds are then remitted to the National Treasury.

[44] Though one thing to note for our current context is that, even when those parties were dissolved, it did not automatically follow that any duly elected representatives were expelled from office. Unless there was legal reason to remove them, any elected officials were simply rendered “Independents” rather than being affiliated with a political party. The constitution stipulates that Diet members can only be expelled by a two-thirds majority vote, though in such circumstances, most politicians choose to step down from their positions before it comes to such drastic measures.

[45] A newspaper or other bulletin officially authorized by the government to publish public and legal notices—in Japan these days, it’s an online site/newsletter.

[46] And they’re often still controversial with progressive activists, as the invocation against Aum was even contemporaneously! Incidentally, Aum’s dissolution lasted for a mere two years before the government panel ultimately declined to make it permanent.

[47] And if you don’t think the HMP had someone watching the official Japanese government website, you’re clearly not taking them seriously.

[48] And possibly more besides; the dialogue in question trails off in a way that suggests that the obstruction charge is only the first in a list.

[49] Start at Yotsubashi Rikiya being inducted when he was still in schoolboy shorts and continue right on up through the people we see in school uniforms in various mass battle scenes involving the MLA rank and file.

[50] And it easily could be thousands. If, say, even 10% of the PLF are minors, that’d be well over 10,000 kids, and thus we’re right back to overcrowding problems, except this time they’re about Japan’s child services programs, and the last thing they need is a new group of kids that numbers a full third of the number of children already in their care in real-life Japan. Naturally, the number only climbs if you think Re-Destro wasn’t counting kids in his initial reckoning of the MLA’s membership.

#bnha analysis#bnha meta#paranormal liberation front#meta liberation army#boku no hero academia#my hero academia#bnha#bnha spoilers#my writing#plf arrests#stillness has salt

79 notes

·

View notes