#they make for more nuanced stories with more symbolism and more layers of interpretation usually. why should there be realism in a

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i hope ruby gets a well-that’s-alright-then-style notdeath. on the one hand it will make haters mad because oh no not another companion with an impermanent end (and i like to see haters mad) on the other it would require creativity to depict this in a new way + i love all the implications i love the dark fairytale quality of these companion exits i love my un-undead schrodinger’s women

with the way the legend of ruby sunday is titled… legends aren’t usually told about living people. legends are stories of the bygone past, of an age long since over, fictionalised and overgrown with folklore like barnacles sticking to an abandoned shell. there is such a thing as a living legend, but they’re exceedingly rare. the unmistakeable raven’s call in the 73 yards teaser, the trailer’s cut to fifteen crying alone after promising to cherry he’d protect her daughter… the foreshadowing is clear as day…

and yet. there’s one massive HOWEVER. ruby appears in s15: millie’s been spotted on set filming it. which leads me to believe — the doctor isn’t one to take the time travel route and revisit companions that in his future are genuinely dead. that would hurt too much, it would cause unnecessary trauma and could break the timeline. that must mean ruby stays alive in some way. ish. she’s alive and a legend and a mystery. girl-ballad girl-song girl-paradox

here she is, fading out.

p.s.: thesis statement on moffatgirls from the tags i left on somebody else’s post about charley pollard.. well it belongs here since it’s basically the semiotic hurricane swirling around ruby at the moment :)

#on a personal level what interests me about these characters is precisely what gets them labeled as being subject to#misogynistic writing by pop-feminist video-essayists. as an autistic girl* (*ish) however; i find female characters that#aren’t quite ‘normal people’; women who represent an idea or concept or are a puzzle to be solved or a manic pixie dream girl to be#more and in a way far more interesting than a girl-next-door-type universally relatable protagonist#they make for more nuanced stories with more symbolism and more layers of interpretation usually. why should there be realism in a#fantastical narrative? similarly i like characters that are haunting the narrative or dead before it began (big locked tomb fan if you#didn’t know) and like. not to be tvtropes but the lost lenore archetype. dead woman who spurs the hero on to recklessness or revenge.#i identify with that dead girl. the laura palmers of the world. set the story in motion without#necessarily having agency. maybe it’s something to do with my#constant background radiation of passive suicidality. in a fun whimsical way :) i would never kill myself but i don’t want to be a real#person. i want to be objectified but not necessarily in a k*nky s*xual way (that too) in a princess in a tower way#the ultimate femme fantasy innit? there’s something about it. hashtag problematic hashtag conforming to gender roles#10000 tags be upon ye#ruby sunday#millie gibson#doctor who#dw#steven moffat#clara oswald#fifteen#fifteenth doctor#twelveclara#amy pond#charley pollard#river song#donna noble#ncuti gatwa#doctor who meta#jamie.txt#haunting

79 notes

·

View notes

Note

.... Omg! Can you please give us analysis of each character and how they are portrayed in the book and then the movies?

Oohh ok! (I’m just gonna go thru the characters and how they are in the book vs how they are usually portrayed in adaptations. These things do not apply to every single adaptation, or even necessarily one specific adaptation, full disclosure, lol) (also this will be very long, so, it’s under the cut.)

Mina:

~ In the book: kind, sweet, caring, motivated, intelligent, interesting, funny. I could go on and on. The protagonist. She IS the moment. She could defeat Dracula without the men but the men could not defeat Dracula without her. I said what I said.

~ In adaptations: typically kind, but may or may not be any more intelligent than the men. Typically portrayed as a damsel in distress, though in the book she isn’t. Almost always Dracula’s love interest. Sometimes she even low-key betrays the Crew to help him. Her personality is very often reduced to one or two traits/archetypes so she can better fit the role of Dracula’s love interest.

Jonathan:

~ In the book: Damsel in distress. He can sometimes come across as boring, because he’s the only very average person in the book, but that’s because he’s supposed to be. It’s a compare and contrast type of thing. Even then, he’s incredibly brave, and incredibly determined. He represents the average person, rising up to the challenge.

~ In adaptations: oh, Jonathan?? You mean the only reason why Mina and Dracula can’t bone??? Yeah but it’s fine if Mina cheats a little bc also he’s an asshole for no reason :////

Lucy:

~ In the book: A delight. Absolute angel. Everyone loves her and she loves everyone but not always in the way they want. If she could she would move all of her friends into a little cottage and bake bread and make tea for them for the rest of forever. Part of the reason why her transformation into the Bloofer Lady is so scarring is because she was genuinely so good-hearted before that.

~ In adaptations: lol she has three suitors so she must be suuuuper promiscuous (side note: not a bad thing but most adaptations portray it as such), and also because of that she definitely wanted Dracula to turn her into a vampire.

Arthur:

~ In the book: Lucy’s fiancée. Also he’s fuckin loaded so he helps fund the whole expedition. Interpretations of him change kinda drastically because he’s not given much canon personality or back story, but he’s overall a pretty decent guy. He can be mean but, like, in a loving way.

~ In adaptations: if he’s there at all he’s usually Just Some Guy. Which, like. fair.

Jack:

~ In the book: a psychiatrist who desperately needs to see a psychiatrist but he is not self aware enough to know this. Used to be Van Helsing’s student. He definitely can be an ass (especially to Renfield), but it’s usually more that he just doesn’t think how his actions affect other people all the way through than him actively being a terrible person on purpose, if that makes sense. Him and his interest in science and technology symbolize the heralding of the new age, which is in contrast with Dracula, who is only ever “living” in the past (bedum tsss).

~ In adaptations: sometimes he’s Van Helsing’s peer rather than ex-student. Usually he doesn’t still keep a phonograph, or even an active interest in technology, which is...a disservice. He can either be nice, or mean, usually not very nuanced or interesting. Honestly I feel like usually in adaptations he’s kinda just used as the gap to get Van Helsing there and then he does nothing after that.

Quincey:

~ In the book: literally the guy who kills Dracula. A Texan, as well, which seems funny now but at the time it was a fairly common trope to add in a foreigner. He’s pretty calm always, especially in a crisis, and also willing to step up and do whatever’s needed of him. And, again, he literally kills Dracula. Easily one of the more important characters in the book, except he doesn’t keep a diary so most people don’t acknowledge this. Also at one point it’s stated he’s rich af iirc so that’s funny.

~ In adaptations: what do you mean we should add the guy who killed Dracula??? Nah it’ll be fine without him

Van Helsing:

~ In the book: he’s the hero of the story (not the protagonist, that’s separate). Him and Dracula are character foils. He’s the guy who knows everything about vampires, and also the guy who specifically knows how to stop Dracula. Even then, he isn’t a professional vampire hunter, or even, like, an expert. He just happens to know a shit ton about this. His name means “father of multitudes” and he is the Designated Dad of the group. He probably makes everyone hot cocoa and tells them weird stories about spiders drinking oil from lamps after a long day.

~ In adaptations: murder grandpa is an asshole who also has no idea what he’s talking about because it makes Dracula look better

Count Dracula:

~ In the book: the villain. He could represent a lot of things — anything from a plague, to the past creeping up and not staying buried where it should, to Stoker’s internalized homophobia, to Stoker’s own xenophobia or antisemitism, or all of the above, or none. He has a lot of layers and each layer is a new level of villainy. We don’t know a lot about him, admittedly — who he was in life, why he became a vampire, what all of his powers are, or even his motivations for coming to London. He can represent any evil we want at all, which makes him a very affective villain. Also he’s supposedly related to Atilla the Hun which is funny af to me for no reason

~ In adaptations: incel!Vlad III

Renfield:

~ In the book: admittedly, he does not have much baring on the plot. He tends to act as a meter for how close Dracula is at any given moment, until his death when Mina takes over that role. However, he introduces many themes and topics into the story: insanity, corruption, idealization of evil, etc., and he and Lucy work together to showcase how vampirism corrupts and how it can destroy even relatively innocent people. Even though Renfield has a bit of a reputation of being violent and volatile, he only ever really does something violent once, which wasn’t even entirely of his own volition and he sacrifices himself for the greater good.

~ In adaptations: oh no scary evil insane man1!!11! he’s obviously just horrible it’s not like Dracula is manipulating him!11!! if Dracula were to manipulate him then Dracula wouldn’t be a sympathetic antihero :(((

The Three Weird Sisters:

~ In the book: the antithesis to Lucy’s suitors. They are supposed to be seductive, and dangerous, above all. They might be Dracula’s victims, or they could be some other vampires unrelated, we don’t really know. Not much is said about them and that’s likely very much on purpose. They have the same air of mystery about them as Dracula does, if not more. A lot of the horror in this book is based in the fear of the unknown.

~ In adaptations: walking boobs with fangs. Usually so much is changed about the story that none of the above is even relevant or can be applied to them.

Anyways thanks for the ask and I hope this answers your question :)

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess or witch: how Anthy and Azula are framed by their narratives

“A girl who cannot become a princess is doomed to become a witch.”

Revolutionary Girl Utena is probably my favorite anime. It scratches all my English major itches for symbolism, motifs, complex characters, and layered narratives. If you haven’t seen it before, be forewarned that it does depict intimate partner violence, rape and sexual abuse. It’s not gratuitous or titillating in any way (*glares at Game of Thrones*), but the series doesn’t hide from it.

One of my favorite things about Revolutionary Girl Utena is the way it comments on how we interpret characters and stories. The series does a phenomenal job of peeling back the layers of the stories and characters, so we see the truth behind them. These truths are usually a lot harder to fit into the neat categories we assign to the characters. To make it even more awesome, the narrative explicitly addresses the role of gender in all this.

No other character embodies these complexities more than Anthy Himemiya. At first, we’re encouraged to see Anthy as a damsel in distress, a walking doormat who seems to attract people who bully and abuse her. Later on, we find out that Anthy’s a lot more powerful than she lets on, and there’s more going on behind those eyeglasses than we assumed. Knowing this, we’re more inclined to vilify her. By the end, we find out what really makes her tick and the trauma she’s dealing with, and it smashes those simplistic notions of who she is.

By contrast, Western animation seems allergic to embracing the nuance and complexity within the stories and characters it creates. Perhaps it’s hamstrung by being “for kids,” so it pulls back from anything that veers too far from the black-and-white morality mold.

Consider Avatar: The Last Airbender.

I make no bones about being an Azula fangirl. She’s my favorite, bar none. You could say that I love the character Azula more than AtLA, and you’d be right. I wouldn’t have much interest in the show without her. It’s not a quality thing. The simple fact of the matter is the show came out after I was already grown, after my tastes and standards have been set by animated narratives that, in my opinion, surpass ATLA in story and character.

Then there’s Azula. Complex, layered Azula who has so much going on,. There’s a reason why I compared her to Hamlet’s Ophelia, and there’s a reason why I’m comparing her to Revolutionary Girl Utena’s Anthy right now.

Anthy and Azula couldn’t be more dissimilar in temperament. But the big thing they have in common is that they are bound to the wills of older male relatives who are supposed to love and protect them but instead manipulate and exploit them, and they bear the brunt of the hatred for the things they do in service to these men.

The difference is that Revolutionary Girl Utena explicitly challenges a one-dimensional interpretation of Anthy’s character. When you look at Anthy, if you only see a princess or a witch, you’re not seeing the real Anthy. You’re seeing what you’ve been taught to see in female characters (and women and girls in general).

ATLA, on the other hand, doesn’t have that commentary running through it. We’re not discouraged from reading Azula as just crazy or just evil. We constantly remind ourselves and each other that Azula is bad, bad, bad, and the narrative doesn’t ask us to resist that impulse or ask where it comes from.

Which is a shame because there’s so much going on with her that has yet to be explored.

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess or witch: how Anthy and Azula are framed by their narratives

“A girl who cannot become a princess is doomed to become a witch.”

Revolutionary Girl Utena is probably my favorite anime. It scratches all my English major itches for symbolism, motifs, complex characters, and layered narratives. If you haven’t seen it before, be forewarned that it does depict intimate partner violence, rape and sexual abuse. It’s not gratuitous or titillating in any way (*glares at Game of Thrones*), but the series doesn’t hide from it.

One of my favorite things about Revolutionary Girl Utena is the way it comments on how we interpret characters and stories. The series does a phenomenal job of peeling back the layers of the stories and characters, so we see the truth behind them. These truths are usually a lot harder to fit into the neat categories we assign to the characters. To make it even more awesome, the narrative explicitly addresses the role of gender in all this.

No other character embodies these complexities more than Anthy Himemiya. At first, we’re encouraged to see Anthy as a damsel in distress, a walking doormat who seems to attract people who bully and abuse her. Later on, we find out that Anthy’s a lot more powerful than she lets on, and there’s more going on behind those eyeglasses than we assumed. Knowing this, we’re more inclined to vilify her. By the end, we find out what really makes her tick and the trauma she’s dealing with, and it smashes those simplistic notions of who she is.

By contrast, Western animation seems allergic to embracing the nuance and complexity within the stories and characters it creates. Perhaps it’s hamstrung by being “for kids,” so it pulls back from anything that veers too far from the black-and-white morality mold.

Consider Avatar: The Last Airbender.

I make no bones about being an Azula fangirl. She’s my favorite, bar none. You could say that I love the character Azula more than AtLA, and you’d be right. I wouldn’t have much interest in the show without her. It’s not a quality thing. The simple fact of the matter is the show came out after I was already grown, after my tastes and standards have been set by animated narratives that, in my opinion, surpass ATLA in story and character.

Then there’s Azula. Complex, layered Azula who has so much going on,. There’s a reason why I compared her to Hamlet’s Ophelia, and there’s a reason why I’m comparing her to Revolutionary Girl Utena’s Anthy right now.

Anthy and Azula couldn’t be more dissimilar in temperament. But the big thing they have in common is that they are bound to the wills of older male relatives who are supposed to love and protect them but instead manipulate and exploit them, and they bear the brunt of the hatred for the things they do in service to these men.

The difference is that Revolutionary Girl Utena explicitly challenges a one-dimensional interpretation of Anthy’s character. When you look at Anthy, if you only see a princess or a witch, you’re not seeing the real Anthy. You’re seeing what you’ve been taught to see in female characters (and women and girls in general).

ATLA, on the other hand, doesn’t have that commentary running through it. We’re not discouraged from reading Azula as just crazy or just evil. We constantly remind ourselves and each other that Azula is bad, bad, bad, and the narrative doesn’t ask us to resist that impulse or ask where it comes from.

Which is a shame because there’s so much going on with her that has yet to be explored.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

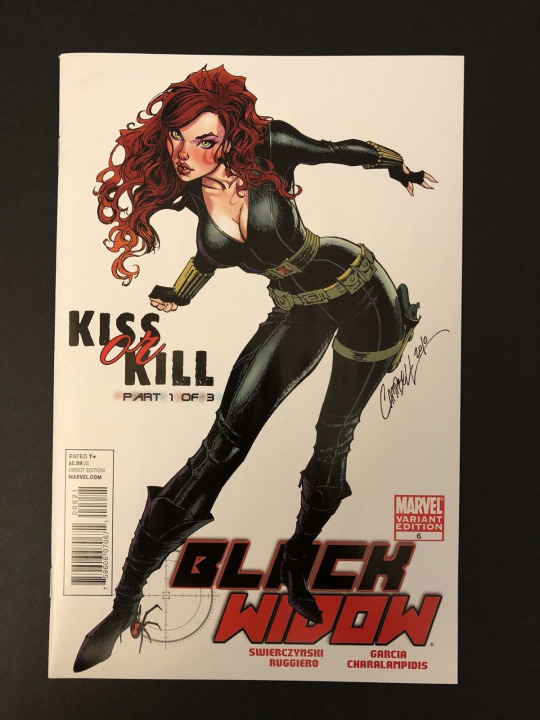

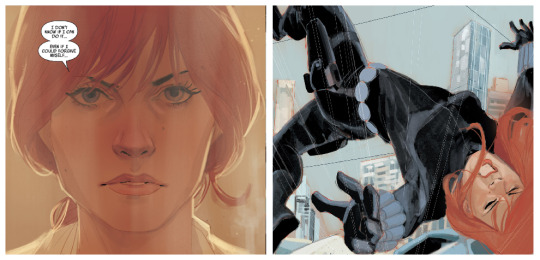

OCD Marvel Costume Series: Black Widow

Ever since I did that post about Captain America’s theoretical onesie and the evolution of his costume, I’ve gotten a lot of requests to do a similar OCD breakdown analysis about Black Widow’s.

After Cap and Bucky, Widow’s easily my favourite MCU character, so I am all too happy to break it down. But just know this required me to wade through so many disgusting male comments about her costume and body that I wanted to flip my desk and set it on fire. Repeatedly. You’re welcome.

Here are the six costumes I’ll be looking at from 2010-2018.

From L to R: Iron Man 2, Avengers, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Captain America: Civil War, and Avengers: Infinity War.

Putting the rest under a read more because shit’s gonna get long.

Let’s begin: Iron Man 2.

This is the first time we meet Natasha in the MCU franchise, and I don’t know about you guys, but I remember there being a LOT of hype surrounding Scarlett being cast in a totally non-objectifying way. <_<

Just kidding. Here’s actual footage of every straight man watching/starring in Iron Man 2 when Nat’s on screen:

This, I think, is a good place to add a caveat that it’s difficult to address Natasha’s looks and clothing without sounding like I’m criticizing her appearance and sexuality, including her ability to weaponize those things or the fact that she is entitled to enjoy them in any way she likes. As a character, certainly she is, and to me that’s one of the really interesting aspects of her personality and an incredible skill. As a woman, those are things not worthy of criticizing, IMO. But the films present a grey area because they are all directed by men, and to a large extent for men. So it’s hard to find the line between what is meant to entice audiences and what is meant to tell us something important about who Nat is, and to what extent the latter is the original intent of the costume choices. How do you extricate the character from the male gaze when the male gaze permeates so much of comic book culture, and by extension the MCU? Let’s not forget how many gratuitous ass shots there are of Natasha in a given movie, although the Russos generally do a good job of evening the playing field by liberally sprinkling in plenty of Cap ass shots too. The Russos are like the salt baes of equal-opportunity and gender-neutral ass shots.

But back to Natasha. In Iron Man 2, she spends most of the movie in sexy wiggle dresses or low-cut blouses, presenting herself as an object of desire for all the men in the film (possibly some of the women) and a thorn in Pepper Potts’s side until they join forces against Tony. (Obviously her intention, since Natasha weaponizes everything about herself, but it was also pretty clearly for audience titillation as much as the character never does anything by accident.)

But then, surprise! It’s revealed she’s the Black Widow and capable of kicking more ass than just about anyone else in the film/on the planet, and can even do it in a skintight catsuit and crazy hair flying in her face at all times!

Natasha’s suit is probably the least functional in this movie because it’s designed to look like a sexy female comic book hero costume, not something a real agent would wear in a believable conflict situation. Or maybe they would, I don’t know. I’m not a spy. But objectively speaking, she has a totally useless belt with the Black Widow symbol around her middle, then the tactical belt, holsters, etc. The fabric looks shiny and stretchy but isn’t leather. That being said, you can’t get much more spot on in terms of the visual interpretation, if you look at how she’s drawn by J Scott Campbell. I am not positive whether IM2 Widow is an interpretation of this artist’s illustration or vice versa, but either way, she translates from film to comic and back again pretty flawlessly.

Just don’t even get me started on the hair because w h a t. Tell me you can’t hear it crackling when you look at this gif. Go on, I dare you.

No wonder ScarJo switched to wigs after this movie.

Ironically, even though this costume is pretty ridiculous in terms of offering any kind of practicality or protection from bullets/knives/explosions, I have to point out that Iron Man 2 is the only movie where Black Widow actually wears practical footwear.

Look at those things. Those are flat, FUNCTIONAL boots. You could do all the running, jumping, and punching things you wanted and not feel like your goddamn feet were going to fall off, or worse, plant you on your fucking face because you’re wearing heels into combat. RIP flat Widow boots.

Moving on. Avengers 1.

Much like the other costumes in this film, Natasha’s outfit is still pretty comic book-y, although to a less cartoonish extent than Captain America some. That is pretty much Joss Whedon’s trademark as a director, although shockingly, I felt Widow looked more serious and ready for battle. Alexandra Byrne did the costume design on Avengers and Ultron, as well as Thor and Guardians of the Galaxy (hence the trademark styles in A1 and A2, plus similarities between Natasha and Gamora’s costumes), and she has a distinct touch. Here the nods to practicality include less extravagant hair (though Natasha also has short hair plenty of times in the comics) and the fact that her suit looks like it could deflect a knife (possibly). Even her civilian clothing looks less hyperfeminine than that of Iron Man 2, and it’s here we begin to see that Nat’s outfit of choice is usually some combination of jeans, a jacket, and knee-high boots with a small heel. It always strikes me that this is probably what she’s most comfortable in when she’s not dressed as Black Widow. Even her stance here looks like that of a soldier, less of a stereotypically female pose.

I couldn’t help but feel a lot of this was intentional on Whedon’s part in order to avoid anyone accusing him of sexualizing Natasha and to look like a Real Director Who Takes Female Characters Seriously (TM). So he dresses women more realistically but then just assassinates their character in other ways, as you do. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

As far as her suit is concerned, don’t get me wrong: it’s still textured plastic meant to stretch and allow movement and comfort and cling to certain... assets... and they still haven’t gotten rid of her totally useless Widow belt. But at least she looks a bit more like she means business and less like she’s just there to look hot.

However, in this film they also introduced the infamous heels to her costume.

In the immortal words of Shuri:

Like Cap’s ab window, this is one of those design choices I begrudgingly understand from a movie perspective--it looks ~sexier and ~more feminine and also reduces the height difference between ScarJo and her male costars (plus other female characters like Agent Hill wear heels too, and so does Wonder Woman in the DC franchise. They appear in the Black Widow comics too), but the reality of someone willingly wearing heels in this type of environment makes me want to facepalm real bad. Sure, you can argue fighting in heels is just one of Nat’s special abilities that makes her better than the rest of us, but--that’s probably not why.

And they don’t go away, even when the movie and writing quality drastically improves. Anyone who read my post on Cap’s suits will probably be able to guess that The Winter Soldier is my #1 Marvel film and had some of my favourite costumes in the MCU, and Nat is no exception there.

The way the Russos interpret her, through their writing and their vision for the overall look of the film and the way the costumes are designed (Judianna Makovsky did all the costumes for Winter Soldier, Civil War, and Infinity War, which makes total sense in ways I’ll explain in a moment), also reminds me a bit of Phil Noto and Nathan Edmonson’s Black Widow. Plenty of people might be inclined to disagree with me there, I’m sure, but Noto and Edmonson’s series, tonally and visually, is very similar to TWS in the sense that they feel like political thrillers, and the character styling in the film continues that theme. The story and the way the characters are written and styled crosses genres and blurs the line between comic book, thriller, and real life.

In TWS, Nat looks like a fucking badass, but also somehow more relatable and human despite her perfect hair and flawless skin. TWS was the film where she, for me (along with the rest of the cast, especially Steve), went from being a character to being a person with all the shades of greys, uncertainties, and ambiguities that entails. That’s where the Russos excel, making fictional characters come alive with nuance and layers. Kind of like how you know if they had done a Hawkeye movie, they’d have probably adapted Hawkeye #19.

Their unique way of finding the humanity in comic book characters and situating them in the real world translates interestingly through the costumes. Even her hair is the most natural-looking shade of copper red than any of the other films, where it tends to looks more dyed. Trust me, as someone who spent 9 years trying to achieve the perfect and most natural shade of copper red possible, I know how difficult it is to get right, even if this is obviously a wig.

If you look reeeeal close at the above pic, you can tell she’s graduated from stretchy plastic to something that resembles kevlar or some kind of protective utility material. You can just make out the lines and texture in the fabric. Still stretches and lets her move, obviously still skintight, but upgrades her to a higher degree of real-world believability in the same way the stealth suit did for Cap.

I find the back of her suit interesting too. There’s a panel sewn over her butt that looks identical to the full-seat equestrian breeches I wear riding, which are meant to offer reinforcement and grip. I’m not entirely sure why Nat needs either of those things in combat, but there you have it. (In all seriousness, it could be because the fabric they used is less stretchy or doesn’t hold its shape the same way, so they had to piece it together differently to allow for movement and shape retention through all the stunts.)

Actually, scratch that. Why wouldn’t you need reinforcement and grip when doing this?

Weird butt panel notwithstanding, Nat’s TWS suit also introduces more protective details like leather and sewn-in kneepads, and her Widow belt actually serves to cinch in the costume instead of just sit there pointlessly, leaving her with just the tac belt. Still the dumb heels too, but I promise I’ll get over it. Maybe.

Next: Age of Ultron. People are going to side-eye the shit out of me for saying this, but... Widow’s costume continues to be less ridiculous than, say, Cap’s. Cartoonish, yes, with a lot of frankly baffling design choices, and visually I liked it the least. But weirdly enough, the construction of the suit and the fabric is less ridiculous than it seems at first glance; it looks like it’d actually offer a pretty high degree of protection in the field. Check it out.

There’s a matte leather and a similar kevlar/utility fabric as her suit in TWS, and the Widow belt and the tac belt have been combined into one so there are fewer pointless buckles.

I mean, too bad they ruin it by adding glowing blue parts that make her look like she’s about to go cosplay as Tron as soon as she finishes saving the world, and I will never understand why her gauntlets are suddenly red, but a detail that caught my eye is right on the bodice. See those seams under her bust?

It looks like it could be there just to draw attention to her boobs, but as a former fencer, I can tell you those are almost certainly for a chest plate or removable protective cups. (From a movie costuming perspective, they’re probably to give the bust more definition, as that’s literally an underwire construction. Yes, okay, I realize this. But if we consider the character, a chest plate makes far more sense.) And if you are a woman in a combat situation where you’re getting whacked in the tits a bunch of times, you need a fucking chest plate. She doesn’t appear to be wearing one in the other films, which is as absurd as Cap going into battle without wearing a cup. Have you ever been clocked in the tits before? With a weapon, no less? Because I have, and it’s not fun. It happens to you once, and you’re on Amazon buying a chest plate or protective cups literally the next day. Or, you know, from the toilet immediately after as you sit there crying and cradling your poor bruised boobs.

Another really practical detail is that she has proper kneepads in this costume, which is ideal if you’re sliding around on the ground a lot, or taking hard landings.

BUT WHY DO THEY GLOW IN THE DARK? /despair

Oddly enough, Nat’s suit in Captain America: Civil War was one of my least favourites--initially. But I was wrong to feel that way, and I’ll tell you why. Why didn’t I like it at first? Well, they pick up some of the same details as in TWS and add other more practical things like no-nonsense kneepads, but they also seem to add boning to the bodice of the suit, and lots of piping everywhere on the arms and torso that would probably rub unpleasantly if you were moving around that much. Unnecessary seams=friction. That’s a lesson any equestrian will tell you too.

I also was not a fan of the Farah Fawcett vibe I got from her hair, but that could just be me. Her suit here is functional, overall, but it doesn’t reinvent the wheel or make her look sleek and dangerous in the same way as TWS. It has less... style than her other suits and civilian outfits (which were my fave in this film), and after this many movies, I think we’ve come to associate the Black Widow suit with style and making certain death at her hands/thighs look good.

But there is a point to her suit looking more tactical, which you can better see here. From this angle, she looks almost military, certainly the most military of any of the other films, and that is intentional and significant later on.

Because much like Cap’s uniform carries over to Infinity War, so does Nat’s. That was a clever segue, in case you were wondering.

This is such a departure from anything else Nat wears in the other films that you kind of have to tip your hat at the designer and the Russos and Judianna Makovsky for having such a sharp eye for detail and a knack for letting costume tell a story. Not only does Natasha change her hair and eyebrow colour, but she changes the colour of her suit too, adding in some green and almost entirely eliminating the sex appeal of the other Widow costumes. But the continuity is most impressive of all.

It’s hard to tell, but just like Steve is wearing the same uniform as in Civil War, minus the star he clawed off with his bare hands, Nat is wearing the exact same Widow costume with a tactical vest on top and some new body armour (shoulder and elbow pads). Remember that piping on the arms, legs, and bodice I bitched about a second ago? If you look closely, it’s all clearly visible in the same spots, and it’s obvious the vest just goes over top. Her kneepads and boots are the exact same too. This girl did a complete 180 on her look with nothing more than a tac vest and an emergency appointment with Guy Tang for some blonde balayage.

It’s amazing that Steve and Sam think going incognito involves DIY distressing on their uniforms and growing some playoff beards, but Natasha can become an entirely different person just by changing a few key details. Especially the eyebrows. I once wrote a line in a fic about how her lighter eyebrows in Infinity War totally change the shape of her face. I think that’s a detail everyone noticed in the trailers, how strange she looked with those ultrablonde brows. But that’s perfect for this character and something Nat would intuitively pick up on, because it leaves her almost unrecognizable. Just like makeup can subtly change someone’s face shape, so can eyebrows, but she ditches makeup in Infinity War to the same effect. It’s the makeover equivalent of “walk, don’t run.” Kind of amazing to think she is so many steps ahead of everyone else that she can go down Dick’s Sporting Goods and CVS for nothing more than a tac vest and a box of hair dye, respectively, and literally emerge looking like a different person. When she says she’s figuring out a new cover, this is the stuff she means.

So there you have it. I hope this costume breakdown as as fun for you to read as it was to put together, and I continue to be impressed and occasionally stumped by the design choices made by the MCU costuming departments. They really do know their stuff and how important clothing is to the understanding of a character, and Nat, who is a master of tailoring her look for maximum effect, proves this rule more than almost anyone else.

Thanks for reading! I might tackle Bucky next, so stay tuned.

#natasha romanoff#black widow#avengers#captain america#natasha romanov#marvel#mcu#costuming#costume#fashion#long post

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 29: One Narrow Thread

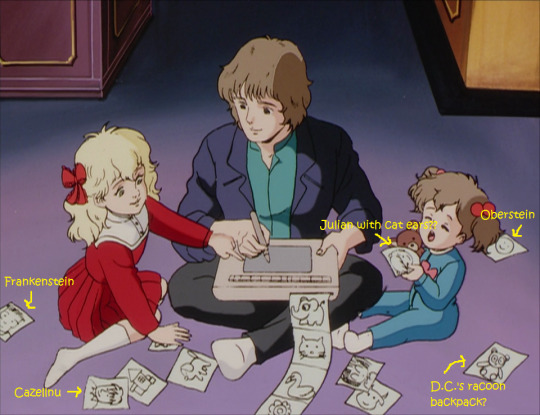

Early 798/489. Adrian Rubinsky meets with Bishop Degsby of the Earth Cult to discuss his plans to aid Reinhard’s forces in capturing Iserlohn and then assassinate Reinhard to seize power for Phezzan. Degsby points out that under this scheme the Earth Cult’s investment in setting up a puppet government on Heinessen would be a wasted resource, but Rubinsky plans to use his financial control over the Alliance government to manipulate them into backing Yang into a corner. Degsby reminds Rubinsky that he owes the Grand Archbishop for his current position and had better tread carefully. Rubinsky sends his minion Kesserling to Remschild to propose a scheme that will ensure that the Empire and Alliance continue to fight each other, while Admiral Kempf attempts to perfectly sync twelve warp engines to avoid trapping all of Geiersberg fortress in null space. ….....Meanwhile back in the actual show we’ve been watching, Yang loses at 3D chess, Julian attempts to drink wine, and Hilda visits Kircheis’s grave.

A Quick Language Rant

“Words are like icebergs floating on the ocean called ‘heart.’” This quote provides the guiding philosophy for this project: LoGH is a text that uses the nuances of language, in concert with facial expressions, body language, symbolism, etc., to point the viewer to deeper layers of meaning in the story being told. As a close reading of the queer narratives in LoGH, this blog attempts to tease out and expose these slightly hidden layers. But…..we are writing in English. You’re reading this in English. The gifs we reference have English subtitles and no sound. And uhh, how do I put this diplomatically…

Every English translation of LoGH sucks.

...Okay that’s a bit harsh. Translation is fucking hard, especially of such a complicated work, and everyone who’s put hours and hours and hours into bringing LoGH to the English-speaking world deserves a hell of a lot of gratitude and credit. We never would have been able to watch the show without them. But. When we get into the nitty-gritty details of analyzing a scene, the fact that often none of the existing translations matches the nuance of the Japanese gets in the way. I’d much rather be plunging into yelling at Cazellnu right now than writing this note, but the conversation between Cazellnu and Yang in this episode is a mess in both sets of subtitles that I have access to, so here we are.

Let’s start with the fansubs, on the left—notice a couple whole clauses that aren’t in the official Hidive subs at all? Care to guess where they come from? That’s right, they come directly from the novels, as does the word “perfect” in Yang’s “perfect parent” line. Hey, I totally get it, fansubbers, the novels are a fantastic resource for figuring out the kanji or double-checking words that are hard to hear. But the dialogue in the anime is not in fact lifted verbatim from the novels; and while not every difference is super meaningful, we are interested in the intentional choices made by the anime staff, and that makes deviation from the books especially ripe for analysis.

The official subs, which are generally quite reliable, are also unsatisfying in this scene. As I’ll discuss below, the word that Yang uses replacing the novel’s “perfect” is 人並みに, hitonami ni, an adverb meaning “like others/as much as anyone else.” The official sub translation makes it sound more like “under normal circumstances” than “like normal people,” and while that’s not a life-altering difference, the nuance is relevant to my analysis. And they got the grammar of the sentence in the last gif here backwards; indeed, neither subtitle translation understood what I believe Yang is saying in those lines, but the English translation of the novel agrees with my interpretation. (Not that the novels don’t have their own translation problems, which is outside the scope of this blog but also frustrating…)

Phew. What all of this means is that before we can even start writing a post, we have to go through a whole process of triangulating all of the slightly different translations of any scene we want to analyze in detail, making sure that we understand the nuances of the language and can convey them accurately. (Not to mention checking the original LD version to make sure no significant changes were made to the animation in the DVD remaster!) In the case of the conversation between Yang and Cazellnu, the subtitles used in this post are my own synthesis based on the fansubs (modified to reflect the actual anime dialogue) and the translation in the novel (where I believe it to be more accurate).

With that out of the way, we are now ready to plunge into the main battle of this episode, so buckle up for....

Yang vs. Cazellnu!

That’s right, we’ve seen Yang battle Imperial fleets to improbable stalemates at Astate and Amlitzer, outsmart the commanders of Iserlohn to capture it from the inside, and annihilate one of his own nation’s fleets on his way to defeating the military coup; but how does Yang the Magician handle the most intimidating of all battles: having dinner with a married friend?? I’ve said before that Icebergs is not a relationship advice column, and nor is it, usually, a tips and tricks guide for dealing with pressure from peers to conform to heteronormative expectations, but hey—when we have the chance to learn from a Master Tactician, we should take it, right?

...Hmm.

...Well in any case, what’s fascinating and important about this conversation is that it does have the back-and-forth tension of a battle, with multiple strikes and counterstrikes: Yang employs a wide range of different strategies tactics to parry the various arguments that Cazellnu makes in his quest to convince Yang of his duty to marry. This conversation is key to understanding both Yang’s attitude toward marriage and family, and the way that Cazellnu often speaks explicitly in the voice of the normative pressures society puts on people to fit into the “married with kids” box. The dynamics of the entire interaction set Yang and Cazellnu up as opponents, and the sum total of Yang’s resistance to all of Cazellnu’s different angles of attack paints a clear picture of his current reluctance to see himself in the role of husband or father.

Yang does indeed provide the first opening to be scolded about marriage, when he takes offense at Charlotte using the suffix -ojichama (an affectionate “uncle”) in contrast to -oniichama, “big brother,” for Julian. Keep this moment in mind; I’ll be coming back to it in…*checks calendar* about eight months.

Immediately Cazellnu frames marriage as a societal obligation, and failure to marry as a “luxury.” Aww Cazellnu you romantic you.

In the previous episode we saw Mittermeyer pushed toward a normative marriage by subtle, insidious pressures—his upbringing within the context of a traditional family and the (possibly unspoken) expectations from his parents that he’d follow that model; the preponderance of visible heterosexual romance in his society. We’ve seen Yang swept along passively into romantic situations in which he was obviously uncomfortable. But Cazellnu’s line right here is the first time that a character has actually given voice to the institutional heteronormativity of society, actually advocated for it in so many words, actually leveraged it to criticize someone’s deviation from that norm.

Bantering with a friend in the abstract is way less uncomfortable for Yang than being thrust directly into a potentially romantic/sexual situation—unlike when Lapp pushed him to dance with Jessica or when Jessica threw herself at him, here there is no immediate danger, no specific person to reject or offend. This is an intellectual battlefield. And so Yang does fight back actively, starting with Tactic #1: appeal to historical precedent.

Note that while in his initial grumbling Yang said he wanted to be called oniichama while *still* a bachelor, now that he’s talking in the abstract rather than about himself he’s taking the even stronger stance that people can be productive members of society while *never* getting married. This line of argument makes sense; history is where Yang feels like an authority, and even the syntax of his “shall I make you a list?” reinforces his expertise here.

If Cazellnu’s thesis were that marrying is the only way to be an asset to society, Yang pointing out the existence of plenty of queer people—er sorry, “lifelong bachelors”—making contributions throughout history would be an effective rebuttal. (No, I don’t think that Yang is consciously talking about queerness, but yes I do think the creators are, through him.) But Cazellnu’s thesis is that participating in marriage and reproduction is an obligation on top of whatever other accomplishments someone might have, and Yang bringing up historical precedent opens the door to Cazellnu pointing out that not only is marriage the norm right now, but it has been for much of history.

In case you think I’m just being overly cute with all the battle analogies, it comes directly from the source material: The narration in the novel here contains lines like “And the point goes to Cazellnu, Julian thought” and “Yang didn’t attempt another counterstrike.”

In the anime, however, Yang does attempt one more counterstrike here, which is important because it’s the closest he gets to just saying “but I don’t want to.”

For Tactic #2, Yang complains that he didn’t pass thirty on purpose; in other words, Cazellnu may think he’s at an age where he ought to be married, but on the inside he doesn’t feel ready for that role. In case there was any suspense about Julian’s feelings on the matter, he is in no rush for Yang to decide he has to get married—keep this line in mind too, as I’ll be coming back to it in a mere six months.

Cazellnu switches the issue from Yang’s feelings to his outward appearance—a subtle but symbolic shift. If only Yang would suck it up and play the proper role, he would become (outwardly at least) a true adult. The issue of Yang’s desires is casually brushed aside.

This entire exchange is good-natured banter—Cazellnu’s intention here, at least on the surface, is to tease Yang, not to seriously condemn him for his choices. But the framework in which people joke is telling; and Cazellnu’s teasing is framed around the assertion that Yang is selfish for neglecting his duty to play the part of husband. Stage one of the battle is interrupted at this point for dinner, and for stage two, during a 3D chess match after dinner, Cazellnu’s joking tone is gone. The topic at issue this time is not just marriage but also parenting; when Cazellnu casually (but correctly) criticizes Yang’s parenting skills, Yang defends himself with Tactic #3: appeal to special circumstances.

Notice that Julian is paralleled to Hortence here in the role of caretaker to the girls. He’s simultaneously being included by implication in the younger generation—as Cazellnu and Yang discuss Yang’s pseudo-parental role in his life—and acting as an adult vis-à-vis the younger kids. At the risk of becoming a broken record...keep this moment in mind, as I’ll be coming back to it in the future.

The key to what Yang’s trying to say here is that adverb I mentioned earlier, hitonami ni, which is a deviation from the dialogue in the novel and therefore something the anime staff thought about explicitly. Hitonami is an adjective meaning average or ordinary (literally “in line with people”), so the adverb form means “like other/most people.” Yang is situating himself as fundamentally outside of the norms that Cazellnu is so fond of imposing: He couldn’t be expected to be a parent like normal people, because he didn’t grow up with a model of a traditional family and because he’s single.

His upbringing is in the past and outside his control; but being single is (on the surface) a choice that he has made—between the tables full of love letters, and Jessica being none too subtle about her continued interest, and everyone on all of Iserlohn knowing that Frederica has a thing for him, it’s always been clear that he’d have options if he were interested. It’s not that his point here doesn’t stand—I agree, the fact that he’s a bachelor who lives alone and has zero interest in or experience with kids did make him a strange choice for Julian’s guardian. But tactically, within this conversation, this was a huge blunder: It opens the door right back up for Cazellnu to continue the marriage guilt trip that was interrupted earlier. And sure enough...

This is such an obvious error that it seems revealing; in Yang’s subconscious, when he’s thinking about why he can’t be expected to be a parent “like most people,” his status as single might feel like something more innate about himself than a temporary circumstance or choice. His shock here is overdone considering the earlier banter. Tactic #4, blaming the ongoing war, is presumably one he’s used before, as Cazellnu is expecting it and doesn’t bother engaging with it directly at all, instead…

...finally delivering his thesis statement on marriage and reproduction clearly. And well, it’s a doozy.

A human being’s greatest duty is to bring forth new life. Damn Cazellnu. The use of the word “duty” (Japanese: 義務, gimu) echoes what Poplan started to say to Konev and Julian about a man’s “duty” to have sex with women; within the first three episodes of the season we’ve had two different characters explicitly describe heterosexual sex and/or reproduction as an obligation. (And throw in the slightly more coded discussion of Mittermeyer’s parents’ “expectations” about his role in society that preface the depiction of his marriage, as well as Reuental’s discussion of his own parents’ unhealthy and unromantic marriage that we haven’t even had time to talk about yet…..hmmmm is it possible that a theme is being established here?)

I can’t emphasize the importance of these lines enough: This is not passive, silent, subtle heteronormativity. This is Cazellnu voicing a view of the main purpose of human life that positions essentially all queerness as not just unusual or different, but specifically a deviation from the greatest duty of human beings. He is not joking. He’s not bantering. This is his worldview.

...And it pisses Yang off. Leaning forward in his seat, setting his brandy glass down with a noticeable thud, furrowing his eyebrows—this is more visibly angry body language than we usually see from Yang. As for the actual content of Tactic #5, well, as much as I love Yang I have to accuse him of a bit of an obnoxious-Reddit-poster argument style here, completely avoiding what Cazellnu actually said and deflecting the topic to something he’d rather be arguing about instead.

Yang: “Yo can we please go back to talking about how much war sucks? I thought I signed up to be on an anti-war show, not to be lectured at about heteronormative social structures…”

The best I can do to relate this reply to what Cazellnu said is that Yang’s either implying that his own record of causing death as a commander morally disqualifies him from being worthy of participating in the whole creation of new life thing, or possibly questioning the wisdom of bringing new life into the middle of a war. Cazellnu seems to take it to be about Yang’s sins, as he counters with—somehow—an even more obnoxious view of the point of reproduction.

“Okay little Timmy, I’ve caused the deaths of approximately three million soldiers in war, so just be a good boy and go do enough good to compensate for that so Daddy doesn’t go to hell, okay?”

Yang is done with this crap by now, and the next gif is a tactical three-for-one: First he points out that for this specific point of Cazellnu’s, about passing along one’s unfinished ambitions to the next generation, there’s no need for one’s protégés to be biological children (#6); then without giving Cazellnu time to respond (perhaps by pointing out that this doesn’t address his original argument about biological imperative to create life), he adds that this whole discussion is moot in the case that there isn’t unfinished ambition to pass along in the first place—again positioning himself as outside the scope of Cazellnu’s arguments (#7); and finally…

...the ultimate maneuver to win any difficult argument: Tactic #8: get up to go pee.

If you’re keeping score, I’d say that the great undefeated Admiral Yang loses this battle badly. Cazellnu is constantly a step ahead, turning Yang’s arguments back around on him and taking advantage of every opening. Yang is a scholar and a brilliant logical thinker, but you can’t fight convictions like “humans have a duty to reproduce” or “being a bachelor is anti-social behavior” with the kind of logic that Yang is practiced in. Heteronormativity is, for Yang, a more difficult opponent than the Imperial army.

Julian

hey-did-we-mention-Julian-has-dual-identities-of-soldier-and-caretaker.gif

The first episode of season two was all about Julian beginning to grow up as a soldier; this episode forms the natural complement by focusing on Julian’s more domestic roles. Back when Julian was first introduced I mentioned that he’s one of the only male characters who embraces more traditionally feminine roles, and in this episode that side of his personality is emphasized—from happily puttering around the kitchen doing laundry and cooking dinner, to helping look after Charlotte and her little sister (henceforth known as Demon Child Cazellnu, D.C. for short, until someone gives me a better explanation for her namelessness…).

Did I say Yang vs. Cazellnu is the main battle of this episode? I should have said it’s second after the epic clash of Gensui vs. the Roomba.

Fun fact: 1600 years in the future everyone has finally gotten over being pedantic about calling it “Frankenstein’s monster”!

It’s not played up in the anime except in background shots like this, but from Julian’s diary it’s clear that, along with Yang, Schenkopp, Poplan, etc., Hortence also serves as a role model and mentor for Julian—he speaks admirably of her ability to quickly turn her new Iserlohn quarters into a true home, and eagerly seeks out new cooking ideas and tips from her.

Julian is by nature a caretaker and nurturer; it’s as much a part of his identity as his urge to fight to protect the things he cares about. I can’t express how fucking cool it is that one of the main protagonists of this show is a teenaged boy who’s completely comfortable putting on an apron and making stew while the washing machine whirs in the background, who looks up to both soldiers and housewives, who spends the evening playing with two little girls until they fall asleep on his lap. The landscape of fiction is generally not filled with men who are defined by empathy and nurturing. It’s so badass and so important that Julian embraces these sides of himself, without feeling the need to somehow reject or outgrow them in order to become a Real Man.™

.....Okay Julian yes you are a badass but please dear god learn how to hold a wine glass.

...and Yang

Icebergs Canon: The reason Julian’s suit and Yang’s pajamas are the exact same color is not the animators being lazy, it’s that both items were gifts from Hortence, who clearly bought them at the same store.

Oooh what is this? Actual backstory about what the fuck Julian is even doing in Yang’s life? One keyword of the storytelling style of LoGH is “patience,” and the show has taken its sweet time offering any real explanation of their whole deal. From episode 3 we know that Yang is Julian’s “guardian,” that Julian’s father was also a soldier, and that the military has paid for Julian’s schooling, but in typical LoGH fashion we’re forced to try to piece the details together ourselves. Here, finally, we’re given a few more snippets: Julian was sent to live with Yang four years ago, when he was twelve, and the person who had the brilliant idea to entrust Yang with a child was none other than…

This is the one skirmish of their battle in which Yang is clearly victorious. Even Cazellnu can’t come up with a defense of this decision. Seriously, Cazellnu…..why.

Poor baffled Yang has absolutely no clue what to do with this small human who showed up at his house and immediately started cleaning up. I love that Yang appears to have repeatedly gotten frustrated while writing something and strewn crumpled drafts all over the room...wtf Yang.

This flashback, which takes place earlier in the episode, complements and reinforces Yang and Cazellnu’s discussion of Yang’s total lack of parental instincts: Although he’s come to care about Julian a lot, he had no enthusiasm for this arrangement when Cazellnu first foisted it upon him. He’s Julian’s guardian not because he wanted a child, but because Cazellnu, tasked with managing supplies of all kinds, had a surplus of war orphans needing housing and pressured his friend into taking one in.

Back in the present, Julian continues to stress about Yang’s disapproval of his military career, leading to my third-favorite failure of the Yang-Bechdel Test:

Julian’s main reaction to his promotion is to wonder how Yang will react; his pout shows that, doing a bit of Icebergs-style analysis himself, he reads between the lines of Frederica’s words to understand that Yang did not act pleased.

This tension is underscored again when Yang, rather than toasting to Julian’s promotion, toasts his safe return. Geez Yang, kinda passive aggressive.

This episode is all set-up, laying out clearly the main themes of Julian’s arc that will continue to develop through the season: 1) He’s awkwardly between child and adult—offered wine but unable to drink it smoothly; playing together with the girls but in a caretaker role; promoted for his heroics in battle but insecure about Yang’s reaction. And 2) his dynamic with Yang is evolving, with question marks about how exactly they’ll relate as he grows up and about how Yang will deal with the reality of his becoming a soldier.

And of course, we’ll be keeping an eye on Gensui’s evolving dynamic with the Roomba as well.

Stray Tidbits

This breathtaking scene in which Hilda visits Kircheis’s grave is one of the first key signs of how seriously the show takes Reinhard’s grief and the hole that Kircheis left in his life going forward. Naturally we’ll be coming back to this moment in the future, so for now I’ll just say, god damn, I have chills.

Worldbuilding alert! Yang’s fleet may be currently stationed on Iserlohn, but lest we forget that it was originally constructed by the Empire, the incredibly fancy paneling of the living quarters is here to remind us. The animators really live and breathe this world and it shows in these details.

I’d be off-brand if I didn’t comment on Hortence Cazellnu finally getting more than a few frames of screen time; but other than being a cheerful hostess and more or less actually knowing how to hold a wine glass (unlike anyone else at the table—I made fun of Julian but in fact he’s just imitating Yang and Cazellnu!), she remains an enigma. Patience, the Hortence Discourse will come.

And then there’s Phezzan, back on its anime bullshit... Seriously wtf is this guy and what’s wrong with his eyes?? I’m scared.

#Legend of Galactic Heroes#Legend of the Galactic Heroes#author:Rebecca#Alliance#Yang#Cazellnu#Hortence#Charlotte#Demon Child#seriously what is her name#Gensui#Julian#gender#heteronormativity#marriage#translation#dammit Sue#dammit Cazellnu

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

DSoD: On Kizuna, Ambiguity, Love...

Going to be honest here when I say I’m not quite sure how to go about expressing my intentions with this, so I hope whoever reads this, reads it with a grain of salt. It’s one of those 4-am in the morning kind of moments of serenity.

The following post explores a little bit about cultural differences, with a few DSOD spoilers. Read at your discretion.

“Love one another, but make not a bond of love: Let it rather be a moving sea between the shores of your souls.” - Kahil Gibran

Today’s starting topic is on kizuna, “bonds”. That which ties people, concepts and objects.

絆 Kizuna | bonds (between people), emotional ties, a connection, a link.

You may find it odd that instead of just saying bonds, I’m specifically using the word kizuna. Well the reason is, there’s a slightly different nuance with kizuna. Much like there is between sayonara and good-bye. Such are the woes and wonders of language. With kizuna, there is something like...a feeling of destiny, something more tangible, something that is able to tether. This concept is popularly depicted using the red string of fate (once, very literally tethered by Pegasus). --- As a side tidbit, it’s also amusingly a homophone to 緤 kizuna (a leash; a tie to bind).

In a previous post I mentioned that in DSoD, Kaiba stated that he too had a bond with the Pharaoh... Well, if you didn’t have a picture of something more concrete before this post, perhaps now you might consider a different nuance behind his words. Something more along the lines of “I have a destiny with him”. And while it was to serve the purpose of being worn by Yugi in the movie, that Kaiba fastened a chain to the Millennium Puzzle leaves a very peculiar aftertaste. But the image of kizuna doesn’t necessarily have to take the form of a string. The Millennium Puzzle itself is the symbol of bonds. Many different, complex pieces of thought and labour to form a whole; throughout the series was broken, repaired and carried by others, connecting whoever it touched... Except, because for the majority of the story, the Puzzle was carried by and is recognized as the bond between Yugi and Yami, we sometimes forget it has gone through a number of hands. Namely, his hand... One of the lines in the movie, Kaiba declares that the Puzzle is his. At the time of watching it, I didn’t really give it much thought because it was just Kaiba being Kaiba, but after writing the previous post, I realized, oh, wait, no, it really did belong to him at one point. --- Well, one point several thousands of years ago when he was Priest Seto. That kind of spins the perspective a bit, because then, it almost seems as if Kaiba reclaiming the Puzzle may have ultimately been his fate. Thus, the notions of kizuna. The nuance between culture and language is such a precarious fine line. Sometimes these things aren’t given much thought.

Now, as for the second topic of this post, ambiguity... There’s a lot about the theme and intent of DSoD that leaves people guessing. The ambiguous atmosphere is in part the intentions of its creators (marketing or otherwise), but I’ve brought this up because I want to explain ambiguity as a cultural phenomenon. It’s something more commonplace in Japanese culture than in North American culture, where things such as arguments are purposely left with room for debate. There usually isn’t a definitive answer, or one truth (unless you’re Conan)...rather, everything is laid in place of relativity. It’s also even rooted into the language where chigau (”that’s not quite right”) is more often expressed than straight up iie (”no”). So what I’m saying is, there is simply no clear cut yes and no answers not just for DSoD but for a lot of Japanese media, because that may just be the general attitude perpetuated by and for the intended audiences. Hence, you’ll often see a lot of series where things are left open-ended or there’s a lot of read-between-the-line moments, and what I find is that a lot of fans from other cultures seem to demand a blunt answer to something that’s meant to be left open for interpretation. As is such with Takahashi-sensei’s celebratory illustration featuring an event post DSoD --- it is but only one of several possibilities... Which now brings me to a very dangerous topic. The third topic.

Let’s talk about love. Let’s talk about love because boy, this has been heavily debated.

I’m of the stance that Kaiba throughout DSoD was mourning because of love. Now, I don’t particularly mean romantic love. It has been iterated time and time again that Kaiba and Yami’s relationship is complex. Just calling it rivalry or friendship doesn’t really encompass the depth and nature of their relationship. The reason I’m calling it love is because love is a such a broad and holistic metaphysical concept with the capacity to encompass a lot of things. Are they lovers, no. Are they in love? Probably not, or probably not in the typical sense. Just, there is a sea of emotions between the two that’s everything short of romantic feelings. I don’t particularly want to call it platonic love either, since that sort of gives off too gentle of a feeling.

Passion, obsession, preoccupation, selfishness, selflessness, desires, demands, and a repetition of fateful encounters...all the qualities often associated with the concept of love. Although I, myself, personally don’t enjoy preoccupations with labels. Being preoccupied with labels and clear-cut stances often divides things that should be looked at as a whole; and so I’m using the term love as a container, instead of a label, if that makes any sense.

To Kaiba, Mokuba is all he has left in the world...but also to Kaiba, Yami had been the center of his existence, a path he always sees himself crossing in the future, but not just simply one instance. It’s through the clashing of their souls that Kaiba feels alive, with only cards between them as their means of communication. He’s overall a brutally harsh man inside and out, but there are a few times where he expresses a deeper layer of emotions that appear so subtly they’re hard to pick up. The manga version of Kaiba is quite different from his anime counterpart. He’s far less excessive and is much more straight to the point. There’s a stronger display of his values and beliefs. Even though I consider DSoD a continuation of the mangaverse, I also feel there is a difference between Takahashi-sensei’s story telling style and flavour, and the end result of the animation studio as a collective. It’s bound to give off a different taste. I thought the Kaiba in DSoD was much more sombre and softer than usual; or it could just be Kenjiro Tsuda’s sweet low husk that gets to me (---one too many Otome CDs, Tsuda-san!).

Anyway, back to what I was saying... A good portion of the movie felt like it was a funeral, with mourning as a theme, where Kaiba was just stuck in a state of perpetual denial and grief. Moreso in the Japanese version than the English version; where in the former he feels unable to replicate Yami Yugi’s likeness for the hologram battle, and in the latter he doesn’t feel a sense of true accomplishment or fulfillment of revenge. Except, y’know, being the forward thinking man he is, he ends up screwing the Acceptance stage, and just makes his own Defying Laws of Physics stage.

I went a couple times in theatre, and my friends all over the world also went a few times, and we all had similar experiences to share. That there seems to be a great majority of viewers in theatres who were in awe at Kaiba’s dedication to Yami/Atem, be it men, women, or children. The theatres were either filled with hollering, clapping, or both; so I really felt as if Kaiba’s dedication and emotions reached out to many viewers. Like, a lot of straight guys confessed this. And when you consider his actions and facial expressions throughout DSoD, he really went above and beyond (literally), denying everything and anyone that stood in his way, going through plans A to Z just to get to the one person he wanted to meet. The first time I watched it I honestly couldn’t believe what I had seen. I saw Kaiba’s obsession and insanity, but also his obscure gentleness and sadness. It’s kind of hard to think of all his great efforts as something less than love.

Anyway, I hope this post has stirred some cogwheels. Last but not least, I kind of wanted to wrap up with talking about death. In a lot of Asian cultures and beliefs, death isn’t the end of the road. It’s not described as nor does it give off the feeling of finite, and so “death” doesn’t really signify the “end of life”. It’s more simply put a transitional pause in time, or relocation of the soul. After earthly life, the soul ascends to a different space, where it (temporarily) rests. A different dimension so to say. You’ll see this depicted a lot. Very famously in say...Dragon Ball, Bleach, and my favourite Houshin Engi, where the soul is held in a different dimension ready for reincarnation, or ready for transformation, or even ready to travel different dimensions (look up transmigration novels, they’re a popular thing...). So what I’m saying is I don’t think Kaiba’s “dead”, and I find it weird that this is so often talked about. That’s not his style. He’s smart and cocky enough to get himself there, so he’s smart and cocky enough to get himself back. I guess he figures if he can’t draw Atem to him, he will go to Atem.

#blog post#dsod spoilers#yu-gi-oh! the dark side of dimensions#gosh im in such a writing mood these days#no but seriously this movie has me so wrecked#seto kaiba

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detention

by Ronan Wills

Thursday, 11 October 2018

Taiwan's history of martial law makes for an excellent portable horror game

Oooh! This is in the Axis of Awesome!~

Horror video games are in an odd spot right now. With my beloved Silent Hill buried beneath the ashes of Konami and the genre dormant in the big-budget space (although Capcom might be giving it a sharp poke back into wakefulness, if Resident Evil 7 and the upcoming Resident Evil 2 remake are anything to go by), gamers looking for a scary good time have increasingly turned to the indie scene to get their fix.

But even that’s starting to stagnate, with a plethora of shabby titles ripping off whatever the latest big trend is. The

Amnesia: The Dark Descent

clones weren’t too bad, but things got really dire once

Five Night’s At Freddy’s

came along.

There is, however, another trend that’s flown under the radar. In recent years, indie horror games from south-east Asia have started to crop up here and there. Developed with an international audience in mind but touting their local culture and mythology as a selling point, these games stand out both due to their point of origin and because they tend to take inspiration from older, more well-regarded horror classics, instead of chasing the latest flash in the pan. The trend seems to have begun with

DreadOut

, a Kickstarted game from Indonesia heavily inspired by the Fatal Frame/Project Zero franchise, and over the last few years more and more have popped up on Steam and other digital platforms.

Jonesing for something spooky to play and realizing that I hadn’t dipped my toe into this particular corner of the market yet, I browsed the Nintendo Switch online store and spotted

Detention

, a Taiwanese game from developer Red Candle. I remembered hearing good things about it when it was released on the PC early last year, but I didn’t know much about it past the basic plot setup and that it’s a 2D side-scrolling game.

Now I’m just kicking myself for not playing it sooner. Everyone who loves classic horror games and who harbours hope for the future of the genre needs to play this game immediately.

Detention

takes place in the 1960s, during the period of Taiwanese history known as the White Terror. The country is under the rule of the nationalist Kuomintang, who use anti-Communist paranoia and tension with neighbouring China to brutally stamp out any hint of dissent among the populace. Our protagonist is Fang Ray Shin, a seventeen year old high school student on the cusp of graduation and adulthood.

Trapped in her school during an unseasonable typhoon, Ray finds herself in a nightmarish version of her familiar world, where ghostly creatures roam the halls and supernatural manifestations force her to confront the events of her recent past--events that she either doesn’t remember, or is trying desperately to forget.

If that setup sounds just a wee bit familiar, then you’ll understand why I sat up and gasped in delight more or less the moment I started playing

Detention

. It’s very clearly and obviously riffing on the older

Silent Hill

games, and unlike many horror games that have tried to do this over the years, it both successfully distills the essence of what made

Silent Hill

so memorable and also manages to retain its own identity.

Despite the 2D presentation,

Detention’s

gameplay is as familiar and comfortable as a favourite pair of slippers. You explore spooky, elaborate environments, searching for clues and items to help you solve puzzles that usually operate on some amount of dream logic. You’ll use items on environmental objects, you’ll hunt down keys, you’ll find statues that look as though they’re meant to be holding something but are currently not holding anything...it’s very familiar survival horror fare. The puzzles are uniformly clever and intriguing; as the game goes on they ramp up in difficulty nicely, eventually requiring the sort of lateral thinking that leads to satisfying “ah ha!” moments. Smart environmental design means that you’ll never fail to progress simply because you didn’t press A on the right piece of background; things you’re meant to interact with are clearly signposted as such.

Where Detention diverges from its inspiration is in enemy encounters. Realizing that combat was always the worst part of classic horror games, Red Candle decided to do away with it entirely in favour of light stealth mechanics. You’ll be looking to avoid

Detention’s

eerie monsters rather than kill them, although I don’t want to spoil the main mechanic by which you do that because it’s pretty original. Enemies aren’t very common--they show up just enough that you’re always worried about running into one, but the game doesn’t throw them at you just for the sake of creating artificial difficulty. Puzzles and plot are the main focus here, particularly in the game's second half.

Said plot is easily

Detention’s

greatest asset. From the very first scene, where a teacher is called away by the school’s political officer for unknown reasons, the game establishes a heavy atmosphere of dread. Its handling of Taiwan’s history really demonstrates the difference between people telling the stories of their own culture and an outsider doing it. A western developer would likely have gone much heavier on the White Terror angle, rather than taking the much more nuanced approach that Red Candle did.

The White Terror is both ever-present and distant. Like all people who live through history, Ray isn’t aware that her experiences will one day seem extraordinary to future generations, or that the society she lives in will come to be viewed as a transient period of darkness between relative stretches of light. This is just her life; she and her classmates and family and teachers have the same daily concerns as anyone else living at any other time, they just happen to exist in an environment where mundane actions and worries can get people killed. Feeling stifled by her surroundings and her home life and yearning to escape, but not knowing what that would look like in practice, Ray takes the kinds of reckless actions that young people the world over are prone to. The fact that her life is engulfed in tragedy as a result isn’t treated as remarkable or even unfair; it’s just the reality of the time and place she happens to live in.

If you’re familiar with

Silent Hill

-inspired games, you’ll know that they like to have Big Plot Twists of a certain nature. Very early on, I figured out what I thought was going to be

Detention’s

Big Plot Twist, but it turns out that the developers were one step ahead of me. Obviously anticipating this reaction from savvy horror fans, they de-twist the twist by basically giving the game away well before the climax. The suggestive symbolism littered throughout the personalized hell that Ray finds herself in lays out the basic fundamentals of what happened to her and the other characters and why she’s in the situation she’s in very clearly, and then a combination of cut-scenes and documents makes it explicit if you’re paying any attention at all. This turns out to be a smart move on Red Candle’s part, as trying to conceal the truth for a Big Plot Twist would likely have failed, and the exact specifics of why everything happened is more interesting than the mere fact that it did happen.

Ray herself is one of the best-written videogame characters I’ve seen in years. Initially encountered through someone else’s perspective, she comes off at first glance as the sort of timid, helpless heroine that horror likes to go in for. But as you peel back the layers of the plot, she turns out to be something very different altogether, both stronger and weaker than she appeared at first, and heart-breakingly relatable even as she’s caught up in circumstances that most of the people playing as her will (hopefully) never experience.

More than just well-written, Detention is subtle and intelligent. Visuals, music, plot and dialogue weave together in eye-opening and unexpected ways, forcing you to constantly re-examine things you saw earlier in new light. It really does reach the heights of meaningful, subtle symbolism that Silent Hill achieved at its best. At times, it might exceed it.

I’m enough of a

Silent Hill

mega fan that that’s high praise indeed. In case it didn’t come through clear enough, I loved every single second of

Detention

, from its mysterious, foreboding opening to it's heart-breaking conclusion. As far as I’m concerned, it’s the successor to the throne of the top tier of videogame horror that Konami relinquished when they started farming Silent Hill out to inexperienced studios, and my anticipation for Red Candles’ next game is physically painful.

All that aside, the game has a few irritating flaws. The English version is plagued with a number of typos and grammatical errors, including the occasional straight up missing word; judging by Red Candles’ English website, it seems like they don’t have any entirely fluent speakers on staff, and it shows. The problems aren’t enough to be a deal breaker by any means, but the mistakes are jarring given how well written the dialogue is, and it’s disappointing to see these errors uncorrected in a version of the game released well over a year after the initial PC release.

At one point, the game brings up a student/teacher relationship which (reading between the lines) appears to have become sexual. Taken at face value, the way the story leaves off this plot point could be read as alarmingly positive. Thinking about it a bit more deeply in context, the rose-tinted way the relationship is portrayed is being filtered entirely through the perspective of the student--who has understandable reasons for feeling that way and wildly mis-interprets other adult dynamics--rather than any detached authorial voice. The only third-party opinion we get on the situation comes from another adult who's generally portrayed as an empathetic type with her head screwed on straight; the fact that she basically calls the teacher involved a predator is, I feel, a pretty clear indicator of where the developers' own feelings lie (there are also some horror elements of the game that don't exactly paint the adult party in a positive light).