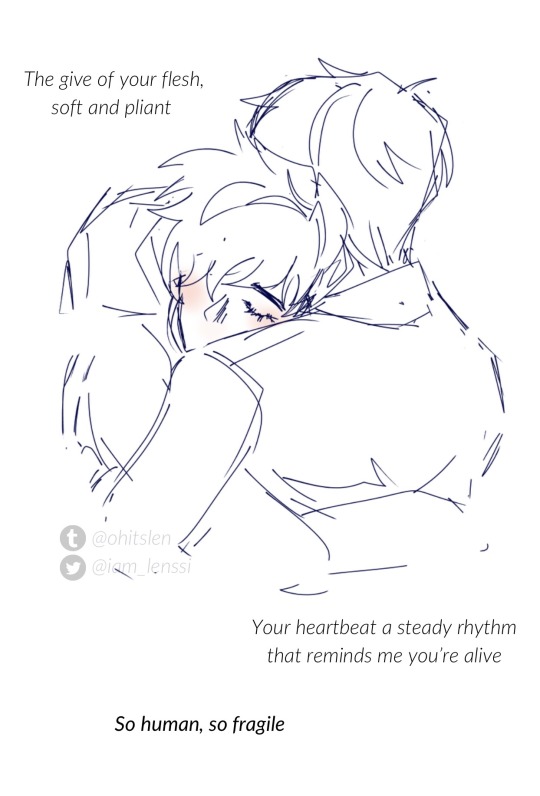

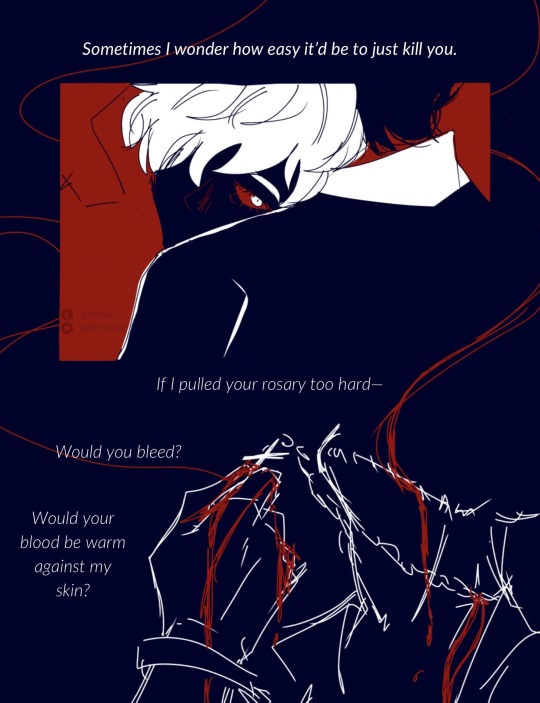

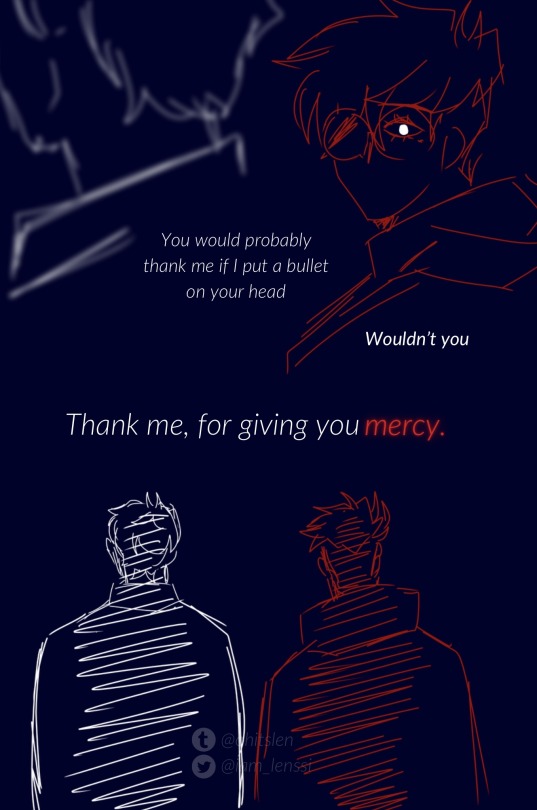

#they are turbo traumatized so it’s even worse at times. this is what I would say one of the tamest instances if that means anything

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Intrusive thoughts

#nothing like thinking about how it’d be to murder your homie. we all do that aaaall the time right#a passion of mine is writing dialogue in a way that you could interchange who says it and it’d still make sense when it comes to Vashwood#they both get insane intrusive thoughts and that’s a matter of fact#they are turbo traumatized so it’s even worse at times. this is what I would say one of the tamest instances if that means anything#Vash would feel so guilty abt them too. bc they don’t feel like his thoughts. it’s almost as if it was someone else’s#they have pointed their guns at each other but never shoot. the thoughts have lost another day <3#Vashwood is: having thoughts and rarely do anything abt them (positive and negative)#everybody who has intrusive thoughts say hell yeah. HELL YEAH!!!#gentle reminder that intrusive thoughts are just that and don’t define you as a person. they are. I’m fact. intrusive#intrusive thoughts#cw intrusive thoughts#tw intrusive thoughts#for those who may need to filter those out#trigun#vash the stampede#nicholas d wolfwood#trigun stampede#vashwood#trigun fanart#vash#wolfwood#nicholas trigun#lenssi draws#lenssi writes#because I wrote the lines first and THEN I did the drawings#still fixated on Vash’s eyes btw if you didn’t notice

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

New Year, Same Me

So we survived 2020 - congratulations!

What a supreme, turbo-load, cluster-fuck of a shit show that year was, just a little bit!-

For me personally, there was a lot going on regardless of a global pandemic that shuts down most of the world. So it’s been a rough time and I’m glad to see this back of it. I would be remiss though if I didn’t take one major thing away from this year and that GRATITUDE! If you’ve reached then end of 2020 then you should have heaps of gratitude. The things I am most grateful for in spite of 2020 being the year that it was;

- Health; my own health and the health of my loved ones. I (so far) have no contracted Covid myself and can luckily only count a small number of people who I know I have had it. Very fortunately, no one I know has passed away from it or because of it so every day I wake up able to breathe, I am grateful!

- Therapy; with 2020 being...well 2020, safe to say my mental health was at it’s limit. I am grateful for having the access and the means to afford private therapy. I am also grateful that because of modern technology I was able to continue therapy via video chat and to enjoy everyone’s physical safety too.

- My Siblings; given my parents separation this year, my siblings and I have all been through a lot. Whilst we are all still very different people and bicker about the in-noxious things that siblings argue over, being able to have them by my side whilst going through this madness so something I’ll never take for granted. My siblings and I don’t get along 90% of the time however they are the only other people who experienced the type of traumatic childhood that we did and although we have differing experiences and issues from those traumas, they get it.

- My Nephew; although I haven’t been able to spend a lot of time with my nephew this year, the time that I have has been even more precious. He is 4 years old and has taken this pandemic all in his stride. I hasn’t moaned about not being able to go to nursery or to see his grandparents that often. He just understands that it’s because of germs and get’s on with his little life. That has been refreshing!

- Technology; now this is a huge catergory that encompasses quiet the variety of things but I am grateful that this pandemic happened in the 21st century and we have the technology available to stay in touch with loved-ones without face-to-face contact. Whether it’s endless zoom quizzes or a simply facetime, ironically, technology has made us all closer! Also, where in the world did Zoom come from - I feel like there was Skype for Business and that’s it, then Zoom came out of nowhere and dominated the game!! I would also like to give a shout out to Podcasts. I have discovered loads during the various lockdowns periods and they have been lifesavers from boredom and much appreciated!

- My Job; as stressful as it has been to work during this pandemic. I have to be grateful for the fact that I work for a medical supplies company and are business hasn’t been too badly affected by the pandemic. Also, I am very fortunate to still have a job and to have still been paid 100% by my employer through the pandemic so can’t complain.

As we head into the New Year, I’m going to try to manage expectation and just say that I hoped it doesn’t get worse! Try and lead this year with love, kindness, self-care and compassion. Remember that just getting through each day is more than enough.

x-x

0 notes

Text

The Volvo Wagon Armada

It was the Woodstock of press drives, a car launch fit for a Swedish king or, better yet, a Volvo wagon nut just like me. To commemorate the launch of the V90, its new and large but chic and sleek carryall, we persuaded Volvo to let us drive one of the first examples on U.S. soil—actually former North American CEO Lex Kerssemakers’ personal car—from the company’s corporate U.S. headquarters (since 1964) in Rockleigh, New Jersey, to the site of Volvo’s first-ever and still very much under-construction U.S. factory in Ridgeville, South Carolina. Then back again. Close to 2,000 miles.

The V90 marks not just a new Volvo wagon but also the most upscale one. It’s also a welcome re-staking of the wagon flag on American soil for the Swedish firm, and we wanted to memorialize it properly. Ditto the new factory, even if it’s not finished being built, a facility made possible by a deep-pocketed new owner—China’s Geely—and generous subsidies from the state of South Carolina. It reflects not just the record sales success Volvo has enjoyed lately but also what a fresh credit line worth more than $11 billion and a friendly state government can do for the spring in one’s business plan.

Volvo loaned us its premium hauler ($53,295 base) and helped us find, organize, and support a group of other wagons representing all eras of the company’s extensive history in the genre, along with the cars’ owners to drive them. I brought along my own light green 1967 122S wagon, bought with 80 original miles on the clock but now with 5,000 miles. A few preflight repairs, and it was ready to go the distance.

Loyal Volvo Club of America (VCOA) members all, the owners who answered Volvo’s call to join the wagon armada were mellow, their cars gloriously representing each decade since the first Volvo wagons of the 1950s and all of the carmaker’s successive wagon eras. We had mostly everything—from a show-winning 1959 445 Duett through the 122, 245, 745, 850, 240, V50, V60, all of the V70s, and a handsome 1800ES from the company’s own collection that accompanied us as far as Delaware. I’m only sorry there isn’t room here to thank everyone by name.

What didn’t turn up was a Mitsubishi-derived V40 or any representative of the 900 series, the ultimate evolution of the 700 series wagons, renamed in honor of its independent rear suspension and, in the case of the one we’d like to have seen, the 960, a straight-six motor. A much better car than it gets credit for, cursed by a short lifespan, its absence was noticed.

The 2017 V90 is svelte and comfortable as it leads its historic counterparts on a 2,000-mile road trip.

The final omission from our cavalcade of Volvos was the 145, the progenitor (1968-’74) of all the “boxes” to come, the cars that cemented the Volvo wagon thing by looking more or less the same for a quarter of a century, from the late ’60s until 1993. But divine providence intervened to correct an unconscionable oversight as we ran across a 145, a runner in only semimoderate dishabille, when we stopped at the Sub Rosa Bakery in Richmond, Virginia.

To ensure this crowd of Volvo volunteers wouldn’t go hungry on our station wagon sojourn, we brought along a couple of knowledgeable food professionals for dining tips along the way. Adam Sachs is the editor of Saveur and drives a V70. Jay Strell, a food communications strategist and fellow Brooklyn dweller, keeps a V50. Along for the ride and some light driving duty, they’d leave their own cars at home. Ditto my old friend, painter Fred Ingrams. He left his car—a too-slow-for-America V50 1.6-liter—at home in Norfolk, England, to come on a forced march to South Carolina as a passenger in a different Volvo wagon. He just hadn’t counted on it being 50 years old. Another drop-in from NYC, Jake Gouverneur, owns a Saab 9-5 wagon, but it has a blown head gasket and isn’t going anywhere.

There would, however, be no shotgun seat for Steve Ohlinger of The Auto Shop of Salisbury, Connecticut. A veteran independent Volvo mechanic, former racer, and (something tells me) former hippie, Steve brought his brown 1984 five-speed manual 245 Turbo, a rare bird. His role, to which he readily assented, was to carry The Knowledge and useful spares for when older pieces of Swedish iron fell in the line of interstate duty—except this happened not once.

Throw in a couple of Volvo PR honchos, a videographer in a V90 Cross Country, an event planner or two, plus our Automobile photographers, and there must have been 25 or more of us driving or riding along at any given moment. Teenaged me would have appreciated this concept.

Funny enough, no one ever did get an exact count on the number of participants. I later realized I was too busy driving to notice. Berkeley County, South Carolina, is a long way from Bergen County, northern New Jersey, especially in an 87-horsepower car with a pushrod engine geared to turn something like 3,800 rpm at 65 mph. The journey seems even longer and more sapping when it is conducted during a two-day rainstorm, with ’60s wipers clapping and a ’60s defroster fan hyperventilating while trying to keep up. But like all the old wagons on this trip, the 122S completed the journey without incident and no worse for the wear.

Swedish cream puff: This 1970s P1800ES “shooting brake” still cuts a stylish profile today.

Older models from the last century are one reason Volvo still has a good reputation to fall back on. Return solely to the early part of the 21st century for your wagon memories, and you’ll find Volvos with some major technical failings to answer for, cars that tarnished the company’s long-running longevity and reliability pitch. We definitely feel better about its new cars nowadays, but there is no predicting what age will bring.

On first acquaintance, though, we are impressed with just about everything to do with the black V90 T6 AWD R-Design wagon we’re driving here, though even in a fast, all-wheel-drive car we hoped for something better than the 26 mpg over some 2,000 mostly highway miles. There were undoubtedly economy-sapping power surges for which we were responsible, as there will always be with 316 hp turbo and supercharged 2.0-liter fours. But there were many more hours of economy-minded highway driving. Results closer to the EPA’s suggested 30 mpg (highway) are not too much to ask for.

The V90 looks great, and its leather-lined interior compares favorably to several Germanic alternatives. If nothing else, it’s airy and different. The car drives and rides especially well, with a nimbleness that belies its size. A little more than 16 feet long, it feels like a big, opulent car in the best sense but drives like a smaller one. Naturally, this executive-priced load hauler also comes with all of the tech and telematics features you expect. That is, expect to love, expect to regret, and one that still has us scratching our heads: Pilot Assist II, Volvo’s second-gen semi-autonomous driving system.

With $600 million of Volvo’s own money invested so far and $200 million in state incentives, Volvo expects to have spent $1 billion on the new factory and to have created 4,000 jobs here by 2030.

The latest Pilot Assist no longer requires you to track a lead vehicle, and it operates in self-driving mode at speeds up to 80 mph, which is nice. (Its predecessor topped out at a considerably less useful 32 mph.) But as “semi-autonomous” suggests, Pilot Assist II only steers for you for 18 seconds at a time, at which point a human must provide input, or the car will come gradually to a halt, which seemed dangerous to me. Another concern? The camera-based system orients the vehicle by using painted road lines on either side of the road.

Will the new V90 still be on public roads decades from now? If its forebears are any indication, the outlook is good.

As you might expect once you know how the system works, the car made large corrections following the white lines into corners, often steering later than we would have with more roll and general back and forth than an attentive, sober skipper would have allowed. Also failing to inspire confidence was the discovery that the V90 seemed willing to veer off the highway around bends where the white paint was worn off or pieces of roadway had fallen away, taking the white line with them. Last-minute driver intervention was most emphatically required. So, as with similar systems from other makers, you can’t fully rely on Pilot Assist II because you still can’t take your eyes off the road. It might make you wonder, beyond tech boasts and consumer beta testing, what is the exact point?

A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity.

Speaking of points, on the ride back to our hotel one night we got a chance to admire Ohlinger’s 245 Turbo in action. By action, I don’t mean heavy acceleration or drifting but merely having its headlamps turned on. That’s because they’re airport runway lights, an unlikely fitment the Volvo guru realized one day was a more or less straight swap, so he tried it, and guess what? They light up a road as if you plan to land a commercial jetliner on it, waking up everyone for miles and inducing post-traumatic stress syndrome in those unlucky enough to be in front of you when they suddenly catch your light show in their rearview mirror. We kind of liked it and made a mental note to look into the conversion. Although, as Ohlinger pointed out, “When they’re great, they’re great. But when they’re not, they’re really not.”

Bonding bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.

Bonding Bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.The following day we headed to the factory site, about an hour’s drive, to inspect it from a distance while photographing all the participants in our station wagon safari. With the plant rising in the background, and the rain miraculously halted, it’s a rare photo that speaks to Volvo’s storied history and equally strong present. Carved here out of swampy woodlands, it represents a minimum investment of $600 million of Volvo’s own money and $200 million in state incentives. Volvo expects to have spent a billion dollars here by 2030 and to have created 4,000 jobs. Perhaps not what you thought of, old timer, when you saw your first 122S wagon all those years ago.

Like the wagons, I was in good shape when we arrived in Charleston for a late lunch. In fairness, however, I must admit I turned over the 122S on several occasions to other drivers while I enjoyed long stints behind the wheel of the V90. The newest, fanciest Volvo wagon yet seemed rocket-ship fast yet delightfully restful, one of the most comfortable rides going, with better seats than most all its modern competition much less those in the 122S, its ancestor from a half century ago. Lack of wind noise lends an amazing quietness to the V90’s cabin, too. Indeed Gouverneur, playing with a decibel-meter app on his phone, explained that the all-wheel-drive model was significantly quieter at 115 mph in the rain with wipers at full chat than the 122S was cruising at 65 mph with wipers off. I can’t speak to the accuracy of this because I was driving, and we all know I would never drive anywhere near that fast.

The Duett was built as a dual-purpose work and personal car and was the only body-on-frame passenger vehicle in Volvo’s U.S. lineup.

This magazine has long maintained that the station wagon format provides the most practical automotive solution for millions more Americans than are buying them now. We understand the auto industry passes time by chasing the latest styling fads, but after being rocked by the ungainly minivan and then crushed by the SUV and the hulking crossovers that followed, the once-best-selling wagon’s pendulum, which swung highest in the 1960s and 1970s, is long overdue to swing back. To the extent that logic plays any part in the matter, which is probably a dubious idea at best, the wagon is more efficient—lighter and more aerodynamic—than its crossover alternative. A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity. Almost half the vehicles sold in Europe are wagons. Is life there so much different? We don’t think so.

Gimmicks and scarcity marketing are cool, I guess, but The whole idea presumes scarcity. And our trip to Volvo’s new plant proved the V90 wagon is way too good to be scarce.

Volvo has had success with sedans and even sports cars in America, but it is best known for its wagons, which are standard fixtures of the landscape in many American neighborhoods to this day. In a world of ever-changing automotive ideals, the Volvo wagon is a basic unit of automotive currency for many, the kind that spans generations. In my life, my parents drove a Volvo wagon, I drove them, my kids drove them, and with luck their kids might. Unlike some makers, Volvo’s never left the wagon field behind, and new proof in the form of the V90 warms the heart.

Yet recognizing fashion and catering to what it thinks most people think they want, the company has hastened in the 21st century to keep its lineup of crossovers and SUVs fresh, lively, and growing. Although there’s really nothing bad to say about the XC60, XC90, and upcoming XC40 models, we still prefer these platforms set up for wagon duty, pure and unadulterated. We don’t begrudge Volvo its high riders—they help pay the rent and the high taxes of super-socialist Sweden. We wish the V90, which shares its platform with the XC90, had as an option a third row of seats as does the SUV.

This affection for the wagon form generally and Volvo’s biggest wagon ever specifically is why we can’t help but second-guess the decision to soft sell the model, which is only available via internet order and not off the showroom floor. Dealers will receive as many of the Cross Country version of the V90 as they can afford to stock but no regular wagon V90s without an internet order, which is a shame.

Seven decades of Volvo wagon evolution stages at the brand’s new South Carolina plant after 1,000 miles of driving.

Gimmicks and scarcity marketing are cool, I guess, but something is wrong. The whole idea presumes scarcity. And our trip to Volvo’s new plant (which won’t build the V90 but rather the 60 series sedan and SUV) proved the V90 wagon is way too good to be scarce. With a little work, it could be the belle of the ball in affluent communities across America, a big ol’ posh station wagon for our times, an anti-SUV. Wagons rule, and if anyone ought to know that, it’s Volvo.

Source: http://chicagoautohaus.com/the-volvo-wagon-armada/

from Chicago Today https://chicagocarspot.wordpress.com/2017/12/18/the-volvo-wagon-armada/

0 notes

Text

The Volvo Wagon Armada

It was the Woodstock of press drives, a car launch fit for a Swedish king or, better yet, a Volvo wagon nut just like me. To commemorate the launch of the V90, its new and large but chic and sleek carryall, we persuaded Volvo to let us drive one of the first examples on U.S. soil—actually former North American CEO Lex Kerssemakers’ personal car—from the company’s corporate U.S. headquarters (since 1964) in Rockleigh, New Jersey, to the site of Volvo’s first-ever and still very much under-construction U.S. factory in Ridgeville, South Carolina. Then back again. Close to 2,000 miles.

The V90 marks not just a new Volvo wagon but also the most upscale one. It’s also a welcome re-staking of the wagon flag on American soil for the Swedish firm, and we wanted to memorialize it properly. Ditto the new factory, even if it’s not finished being built, a facility made possible by a deep-pocketed new owner—China’s Geely—and generous subsidies from the state of South Carolina. It reflects not just the record sales success Volvo has enjoyed lately but also what a fresh credit line worth more than $11 billion and a friendly state government can do for the spring in one’s business plan.

Volvo loaned us its premium hauler ($53,295 base) and helped us find, organize, and support a group of other wagons representing all eras of the company’s extensive history in the genre, along with the cars’ owners to drive them. I brought along my own light green 1967 122S wagon, bought with 80 original miles on the clock but now with 5,000 miles. A few preflight repairs, and it was ready to go the distance.

Loyal Volvo Club of America (VCOA) members all, the owners who answered Volvo’s call to join the wagon armada were mellow, their cars gloriously representing each decade since the first Volvo wagons of the 1950s and all of the carmaker’s successive wagon eras. We had mostly everything—from a show-winning 1959 445 Duett through the 122, 245, 745, 850, 240, V50, V60, all of the V70s, and a handsome 1800ES from the company’s own collection that accompanied us as far as Delaware. I’m only sorry there isn’t room here to thank everyone by name.

What didn’t turn up was a Mitsubishi-derived V40 or any representative of the 900 series, the ultimate evolution of the 700 series wagons, renamed in honor of its independent rear suspension and, in the case of the one we’d like to have seen, the 960, a straight-six motor. A much better car than it gets credit for, cursed by a short lifespan, its absence was noticed.

The 2017 V90 is svelte and comfortable as it leads its historic counterparts on a 2,000-mile road trip.

The final omission from our cavalcade of Volvos was the 145, the progenitor (1968-’74) of all the “boxes” to come, the cars that cemented the Volvo wagon thing by looking more or less the same for a quarter of a century, from the late ’60s until 1993. But divine providence intervened to correct an unconscionable oversight as we ran across a 145, a runner in only semimoderate dishabille, when we stopped at the Sub Rosa Bakery in Richmond, Virginia.

To ensure this crowd of Volvo volunteers wouldn’t go hungry on our station wagon sojourn, we brought along a couple of knowledgeable food professionals for dining tips along the way. Adam Sachs is the editor of Saveur and drives a V70. Jay Strell, a food communications strategist and fellow Brooklyn dweller, keeps a V50. Along for the ride and some light driving duty, they’d leave their own cars at home. Ditto my old friend, painter Fred Ingrams. He left his car—a too-slow-for-America V50 1.6-liter—at home in Norfolk, England, to come on a forced march to South Carolina as a passenger in a different Volvo wagon. He just hadn’t counted on it being 50 years old. Another drop-in from NYC, Jake Gouverneur, owns a Saab 9-5 wagon, but it has a blown head gasket and isn’t going anywhere.

There would, however, be no shotgun seat for Steve Ohlinger of The Auto Shop of Salisbury, Connecticut. A veteran independent Volvo mechanic, former racer, and (something tells me) former hippie, Steve brought his brown 1984 five-speed manual 245 Turbo, a rare bird. His role, to which he readily assented, was to carry The Knowledge and useful spares for when older pieces of Swedish iron fell in the line of interstate duty—except this happened not once.

Throw in a couple of Volvo PR honchos, a videographer in a V90 Cross Country, an event planner or two, plus our Automobile photographers, and there must have been 25 or more of us driving or riding along at any given moment. Teenaged me would have appreciated this concept.

Funny enough, no one ever did get an exact count on the number of participants. I later realized I was too busy driving to notice. Berkeley County, South Carolina, is a long way from Bergen County, northern New Jersey, especially in an 87-horsepower car with a pushrod engine geared to turn something like 3,800 rpm at 65 mph. The journey seems even longer and more sapping when it is conducted during a two-day rainstorm, with ’60s wipers clapping and a ’60s defroster fan hyperventilating while trying to keep up. But like all the old wagons on this trip, the 122S completed the journey without incident and no worse for the wear.

Swedish cream puff: This 1970s P1800ES “shooting brake” still cuts a stylish profile today.

Older models from the last century are one reason Volvo still has a good reputation to fall back on. Return solely to the early part of the 21st century for your wagon memories, and you’ll find Volvos with some major technical failings to answer for, cars that tarnished the company’s long-running longevity and reliability pitch. We definitely feel better about its new cars nowadays, but there is no predicting what age will bring.

On first acquaintance, though, we are impressed with just about everything to do with the black V90 T6 AWD R-Design wagon we’re driving here, though even in a fast, all-wheel-drive car we hoped for something better than the 26 mpg over some 2,000 mostly highway miles. There were undoubtedly economy-sapping power surges for which we were responsible, as there will always be with 316 hp turbo and supercharged 2.0-liter fours. But there were many more hours of economy-minded highway driving. Results closer to the EPA’s suggested 30 mpg (highway) are not too much to ask for.

The V90 looks great, and its leather-lined interior compares favorably to several Germanic alternatives. If nothing else, it’s airy and different. The car drives and rides especially well, with a nimbleness that belies its size. A little more than 16 feet long, it feels like a big, opulent car in the best sense but drives like a smaller one. Naturally, this executive-priced load hauler also comes with all of the tech and telematics features you expect. That is, expect to love, expect to regret, and one that still has us scratching our heads: Pilot Assist II, Volvo’s second-gen semi-autonomous driving system.

With $600 million of Volvo’s own money invested so far and $200 million in state incentives, Volvo expects to have spent $1 billion on the new factory and to have created 4,000 jobs here by 2030.

The latest Pilot Assist no longer requires you to track a lead vehicle, and it operates in self-driving mode at speeds up to 80 mph, which is nice. (Its predecessor topped out at a considerably less useful 32 mph.) But as “semi-autonomous” suggests, Pilot Assist II only steers for you for 18 seconds at a time, at which point a human must provide input, or the car will come gradually to a halt, which seemed dangerous to me. Another concern? The camera-based system orients the vehicle by using painted road lines on either side of the road.

Will the new V90 still be on public roads decades from now? If its forebears are any indication, the outlook is good.

As you might expect once you know how the system works, the car made large corrections following the white lines into corners, often steering later than we would have with more roll and general back and forth than an attentive, sober skipper would have allowed. Also failing to inspire confidence was the discovery that the V90 seemed willing to veer off the highway around bends where the white paint was worn off or pieces of roadway had fallen away, taking the white line with them. Last-minute driver intervention was most emphatically required. So, as with similar systems from other makers, you can’t fully rely on Pilot Assist II because you still can’t take your eyes off the road. It might make you wonder, beyond tech boasts and consumer beta testing, what is the exact point?

A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity.

Speaking of points, on the ride back to our hotel one night we got a chance to admire Ohlinger’s 245 Turbo in action. By action, I don’t mean heavy acceleration or drifting but merely having its headlamps turned on. That’s because they’re airport runway lights, an unlikely fitment the Volvo guru realized one day was a more or less straight swap, so he tried it, and guess what? They light up a road as if you plan to land a commercial jetliner on it, waking up everyone for miles and inducing post-traumatic stress syndrome in those unlucky enough to be in front of you when they suddenly catch your light show in their rearview mirror. We kind of liked it and made a mental note to look into the conversion. Although, as Ohlinger pointed out, “When they’re great, they’re great. But when they’re not, they’re really not.”

Bonding bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.

Bonding Bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.The following day we headed to the factory site, about an hour’s drive, to inspect it from a distance while photographing all the participants in our station wagon safari. With the plant rising in the background, and the rain miraculously halted, it’s a rare photo that speaks to Volvo’s storied history and equally strong present. Carved here out of swampy woodlands, it represents a minimum investment of $600 million of Volvo’s own money and $200 million in state incentives. Volvo expects to have spent a billion dollars here by 2030 and to have created 4,000 jobs. Perhaps not what you thought of, old timer, when you saw your first 122S wagon all those years ago.

Like the wagons, I was in good shape when we arrived in Charleston for a late lunch. In fairness, however, I must admit I turned over the 122S on several occasions to other drivers while I enjoyed long stints behind the wheel of the V90. The newest, fanciest Volvo wagon yet seemed rocket-ship fast yet delightfully restful, one of the most comfortable rides going, with better seats than most all its modern competition much less those in the 122S, its ancestor from a half century ago. Lack of wind noise lends an amazing quietness to the V90’s cabin, too. Indeed Gouverneur, playing with a decibel-meter app on his phone, explained that the all-wheel-drive model was significantly quieter at 115 mph in the rain with wipers at full chat than the 122S was cruising at 65 mph with wipers off. I can’t speak to the accuracy of this because I was driving, and we all know I would never drive anywhere near that fast.

The Duett was built as a dual-purpose work and personal car and was the only body-on-frame passenger vehicle in Volvo’s U.S. lineup.

This magazine has long maintained that the station wagon format provides the most practical automotive solution for millions more Americans than are buying them now. We understand the auto industry passes time by chasing the latest styling fads, but after being rocked by the ungainly minivan and then crushed by the SUV and the hulking crossovers that followed, the once-best-selling wagon’s pendulum, which swung highest in the 1960s and 1970s, is long overdue to swing back. To the extent that logic plays any part in the matter, which is probably a dubious idea at best, the wagon is more efficient—lighter and more aerodynamic—than its crossover alternative. A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity. Almost half the vehicles sold in Europe are wagons. Is life there so much different? We don’t think so.

Gimmicks and scarcity marketing are cool, I guess, but The whole idea presumes scarcity. And our trip to Volvo’s new plant proved the V90 wagon is way too good to be scarce.

Volvo has had success with sedans and even sports cars in America, but it is best known for its wagons, which are standard fixtures of the landscape in many American neighborhoods to this day. In a world of ever-changing automotive ideals, the Volvo wagon is a basic unit of automotive currency for many, the kind that spans generations. In my life, my parents drove a Volvo wagon, I drove them, my kids drove them, and with luck their kids might. Unlike some makers, Volvo’s never left the wagon field behind, and new proof in the form of the V90 warms the heart.

Yet recognizing fashion and catering to what it thinks most people think they want, the company has hastened in the 21st century to keep its lineup of crossovers and SUVs fresh, lively, and growing. Although there’s really nothing bad to say about the XC60, XC90, and upcoming XC40 models, we still prefer these platforms set up for wagon duty, pure and unadulterated. We don’t begrudge Volvo its high riders—they help pay the rent and the high taxes of super-socialist Sweden. We wish the V90, which shares its platform with the XC90, had as an option a third row of seats as does the SUV.

This affection for the wagon form generally and Volvo’s biggest wagon ever specifically is why we can’t help but second-guess the decision to soft sell the model, which is only available via internet order and not off the showroom floor. Dealers will receive as many of the Cross Country version of the V90 as they can afford to stock but no regular wagon V90s without an internet orde from Performance Junk WP Feed 4 http://ift.tt/2yT2zt6 via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

The Volvo Wagon Armada

It was the Woodstock of press drives, a car launch fit for a Swedish king or, better yet, a Volvo wagon nut just like me. To commemorate the launch of the V90, its new and large but chic and sleek carryall, we persuaded Volvo to let us drive one of the first examples on U.S. soil—actually former North American CEO Lex Kerssemakers’ personal car—from the company’s corporate U.S. headquarters (since 1964) in Rockleigh, New Jersey, to the site of Volvo’s first-ever and still very much under-construction U.S. factory in Ridgeville, South Carolina. Then back again. Close to 2,000 miles.

The V90 marks not just a new Volvo wagon but also the most upscale one. It’s also a welcome re-staking of the wagon flag on American soil for the Swedish firm, and we wanted to memorialize it properly. Ditto the new factory, even if it’s not finished being built, a facility made possible by a deep-pocketed new owner—China’s Geely—and generous subsidies from the state of South Carolina. It reflects not just the record sales success Volvo has enjoyed lately but also what a fresh credit line worth more than $11 billion and a friendly state government can do for the spring in one’s business plan.

Volvo loaned us its premium hauler ($53,295 base) and helped us find, organize, and support a group of other wagons representing all eras of the company’s extensive history in the genre, along with the cars’ owners to drive them. I brought along my own light green 1967 122S wagon, bought with 80 original miles on the clock but now with 5,000 miles. A few preflight repairs, and it was ready to go the distance.

Loyal Volvo Club of America (VCOA) members all, the owners who answered Volvo’s call to join the wagon armada were mellow, their cars gloriously representing each decade since the first Volvo wagons of the 1950s and all of the carmaker’s successive wagon eras. We had mostly everything—from a show-winning 1959 445 Duett through the 122, 245, 745, 850, 240, V50, V60, all of the V70s, and a handsome 1800ES from the company’s own collection that accompanied us as far as Delaware. I’m only sorry there isn’t room here to thank everyone by name.

What didn’t turn up was a Mitsubishi-derived V40 or any representative of the 900 series, the ultimate evolution of the 700 series wagons, renamed in honor of its independent rear suspension and, in the case of the one we’d like to have seen, the 960, a straight-six motor. A much better car than it gets credit for, cursed by a short lifespan, its absence was noticed.

The 2017 V90 is svelte and comfortable as it leads its historic counterparts on a 2,000-mile road trip.

The final omission from our cavalcade of Volvos was the 145, the progenitor (1968-’74) of all the “boxes” to come, the cars that cemented the Volvo wagon thing by looking more or less the same for a quarter of a century, from the late ’60s until 1993. But divine providence intervened to correct an unconscionable oversight as we ran across a 145, a runner in only semimoderate dishabille, when we stopped at the Sub Rosa Bakery in Richmond, Virginia.

To ensure this crowd of Volvo volunteers wouldn’t go hungry on our station wagon sojourn, we brought along a couple of knowledgeable food professionals for dining tips along the way. Adam Sachs is the editor of Saveur and drives a V70. Jay Strell, a food communications strategist and fellow Brooklyn dweller, keeps a V50. Along for the ride and some light driving duty, they’d leave their own cars at home. Ditto my old friend, painter Fred Ingrams. He left his car—a too-slow-for-America V50 1.6-liter—at home in Norfolk, England, to come on a forced march to South Carolina as a passenger in a different Volvo wagon. He just hadn’t counted on it being 50 years old. Another drop-in from NYC, Jake Gouverneur, owns a Saab 9-5 wagon, but it has a blown head gasket and isn’t going anywhere.

There would, however, be no shotgun seat for Steve Ohlinger of The Auto Shop of Salisbury, Connecticut. A veteran independent Volvo mechanic, former racer, and (something tells me) former hippie, Steve brought his brown 1984 five-speed manual 245 Turbo, a rare bird. His role, to which he readily assented, was to carry The Knowledge and useful spares for when older pieces of Swedish iron fell in the line of interstate duty—except this happened not once.

Throw in a couple of Volvo PR honchos, a videographer in a V90 Cross Country, an event planner or two, plus our Automobile photographers, and there must have been 25 or more of us driving or riding along at any given moment. Teenaged me would have appreciated this concept.

Funny enough, no one ever did get an exact count on the number of participants. I later realized I was too busy driving to notice. Berkeley County, South Carolina, is a long way from Bergen County, northern New Jersey, especially in an 87-horsepower car with a pushrod engine geared to turn something like 3,800 rpm at 65 mph. The journey seems even longer and more sapping when it is conducted during a two-day rainstorm, with ’60s wipers clapping and a ’60s defroster fan hyperventilating while trying to keep up. But like all the old wagons on this trip, the 122S completed the journey without incident and no worse for the wear.

Swedish cream puff: This 1970s P1800ES “shooting brake” still cuts a stylish profile today.

Older models from the last century are one reason Volvo still has a good reputation to fall back on. Return solely to the early part of the 21st century for your wagon memories, and you’ll find Volvos with some major technical failings to answer for, cars that tarnished the company’s long-running longevity and reliability pitch. We definitely feel better about its new cars nowadays, but there is no predicting what age will bring.

On first acquaintance, though, we are impressed with just about everything to do with the black V90 T6 AWD R-Design wagon we’re driving here, though even in a fast, all-wheel-drive car we hoped for something better than the 26 mpg over some 2,000 mostly highway miles. There were undoubtedly economy-sapping power surges for which we were responsible, as there will always be with 316 hp turbo and supercharged 2.0-liter fours. But there were many more hours of economy-minded highway driving. Results closer to the EPA’s suggested 30 mpg (highway) are not too much to ask for.

The V90 looks great, and its leather-lined interior compares favorably to several Germanic alternatives. If nothing else, it’s airy and different. The car drives and rides especially well, with a nimbleness that belies its size. A little more than 16 feet long, it feels like a big, opulent car in the best sense but drives like a smaller one. Naturally, this executive-priced load hauler also comes with all of the tech and telematics features you expect. That is, expect to love, expect to regret, and one that still has us scratching our heads: Pilot Assist II, Volvo’s second-gen semi-autonomous driving system.

With $600 million of Volvo’s own money invested so far and $200 million in state incentives, Volvo expects to have spent $1 billion on the new factory and to have created 4,000 jobs here by 2030.

The latest Pilot Assist no longer requires you to track a lead vehicle, and it operates in self-driving mode at speeds up to 80 mph, which is nice. (Its predecessor topped out at a considerably less useful 32 mph.) But as “semi-autonomous” suggests, Pilot Assist II only steers for you for 18 seconds at a time, at which point a human must provide input, or the car will come gradually to a halt, which seemed dangerous to me. Another concern? The camera-based system orients the vehicle by using painted road lines on either side of the road.

Will the new V90 still be on public roads decades from now? If its forebears are any indication, the outlook is good.

As you might expect once you know how the system works, the car made large corrections following the white lines into corners, often steering later than we would have with more roll and general back and forth than an attentive, sober skipper would have allowed. Also failing to inspire confidence was the discovery that the V90 seemed willing to veer off the highway around bends where the white paint was worn off or pieces of roadway had fallen away, taking the white line with them. Last-minute driver intervention was most emphatically required. So, as with similar systems from other makers, you can’t fully rely on Pilot Assist II because you still can’t take your eyes off the road. It might make you wonder, beyond tech boasts and consumer beta testing, what is the exact point?

A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity.

Speaking of points, on the ride back to our hotel one night we got a chance to admire Ohlinger’s 245 Turbo in action. By action, I don’t mean heavy acceleration or drifting but merely having its headlamps turned on. That’s because they’re airport runway lights, an unlikely fitment the Volvo guru realized one day was a more or less straight swap, so he tried it, and guess what? They light up a road as if you plan to land a commercial jetliner on it, waking up everyone for miles and inducing post-traumatic stress syndrome in those unlucky enough to be in front of you when they suddenly catch your light show in their rearview mirror. We kind of liked it and made a mental note to look into the conversion. Although, as Ohlinger pointed out, “When they’re great, they’re great. But when they’re not, they’re really not.”

Bonding bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.

Bonding Bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.The following day we headed to the factory site, about an hour’s drive, to inspect it from a distance while photographing all the participants in our station wagon safari. With the plant rising in the background, and the rain miraculously halted, it’s a rare photo that speaks to Volvo’s storied history and equally strong present. Carved here out of swampy woodlands, it represents a minimum investment of $600 million of Volvo’s own money and $200 million in state incentives. Volvo expects to have spent a billion dollars here by 2030 and to have created 4,000 jobs. Perhaps not what you thought of, old timer, when you saw your first 122S wagon all those years ago.

Like the wagons, I was in good shape when we arrived in Charleston for a late lunch. In fairness, however, I must admit I turned over the 122S on several occasions to other drivers while I enjoyed long stints behind the wheel of the V90. The newest, fanciest Volvo wagon yet seemed rocket-ship fast yet delightfully restful, one of the most comfortable rides going, with better seats than most all its modern competition much less those in the 122S, its ancestor from a half century ago. Lack of wind noise lends an amazing quietness to the V90’s cabin, too. Indeed Gouverneur, playing with a decibel-meter app on his phone, explained that the all-wheel-drive model was significantly quieter at 115 mph in the rain with wipers at full chat than the 122S was cruising at 65 mph with wipers off. I can’t speak to the accuracy of this because I was driving, and we all know I would never drive anywhere near that fast.

The Duett was built as a dual-purpose work and personal car and was the only body-on-frame passenger vehicle in Volvo’s U.S. lineup.

This magazine has long maintained that the station wagon format provides the most practical automotive solution for millions more Americans than are buying them now. We understand the auto industry passes time by chasing the latest styling fads, but after being rocked by the ungainly minivan and then crushed by the SUV and the hulking crossovers that followed, the once-best-selling wagon’s pendulum, which swung highest in the 1960s and 1970s, is long overdue to swing back. To the extent that logic plays any part in the matter, which is probably a dubious idea at best, the wagon is more efficient—lighter and more aerodynamic—than its crossover alternative. A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity. Almost half the vehicles sold in Europe are wagons. Is life there so much different? We don’t think so.

Gimmicks and scarcity marketing are cool, I guess, but The whole idea presumes scarcity. And our trip to Volvo’s new plant proved the V90 wagon is way too good to be scarce.

Volvo has had success with sedans and even sports cars in America, but it is best known for its wagons, which are standard fixtures of the landscape in many American neighborhoods to this day. In a world of ever-changing automotive ideals, the Volvo wagon is a basic unit of automotive currency for many, the kind that spans generations. In my life, my parents drove a Volvo wagon, I drove them, my kids drove them, and with luck their kids might. Unlike some makers, Volvo’s never left the wagon field behind, and new proof in the form of the V90 warms the heart.

Yet recognizing fashion and catering to what it thinks most people think they want, the company has hastened in the 21st century to keep its lineup of crossovers and SUVs fresh, lively, and growing. Although there’s really nothing bad to say about the XC60, XC90, and upcoming XC40 models, we still prefer these platforms set up for wagon duty, pure and unadulterated. We don’t begrudge Volvo its high riders—they help pay the rent and the high taxes of super-socialist Sweden. We wish the V90, which shares its platform with the XC90, had as an option a third row of seats as does the SUV.

This affection for the wagon form generally and Volvo’s biggest wagon ever specifically is why we can’t help but second-guess the decision to soft sell the model, which is only available via internet order and not off the showroom floor. Dealers will receive as many of the Cross Country version of the V90 as they can afford to stock but no regular wagon V90s without an internet orde from Performance Junk Blogger Feed 4 http://ift.tt/2yT2zt6 via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

The Volvo Wagon Armada

It was the Woodstock of press drives, a car launch fit for a Swedish king or, better yet, a Volvo wagon nut just like me. To commemorate the launch of the V90, its new and large but chic and sleek carryall, we persuaded Volvo to let us drive one of the first examples on U.S. soil—actually former North American CEO Lex Kerssemakers’ personal car—from the company’s corporate U.S. headquarters (since 1964) in Rockleigh, New Jersey, to the site of Volvo’s first-ever and still very much under-construction U.S. factory in Ridgeville, South Carolina. Then back again. Close to 2,000 miles.

The V90 marks not just a new Volvo wagon but also the most upscale one. It’s also a welcome re-staking of the wagon flag on American soil for the Swedish firm, and we wanted to memorialize it properly. Ditto the new factory, even if it’s not finished being built, a facility made possible by a deep-pocketed new owner—China’s Geely—and generous subsidies from the state of South Carolina. It reflects not just the record sales success Volvo has enjoyed lately but also what a fresh credit line worth more than $11 billion and a friendly state government can do for the spring in one’s business plan.

Volvo loaned us its premium hauler ($53,295 base) and helped us find, organize, and support a group of other wagons representing all eras of the company’s extensive history in the genre, along with the cars’ owners to drive them. I brought along my own light green 1967 122S wagon, bought with 80 original miles on the clock but now with 5,000 miles. A few preflight repairs, and it was ready to go the distance.

Loyal Volvo Club of America (VCOA) members all, the owners who answered Volvo’s call to join the wagon armada were mellow, their cars gloriously representing each decade since the first Volvo wagons of the 1950s and all of the carmaker’s successive wagon eras. We had mostly everything—from a show-winning 1959 445 Duett through the 122, 245, 745, 850, 240, V50, V60, all of the V70s, and a handsome 1800ES from the company’s own collection that accompanied us as far as Delaware. I’m only sorry there isn’t room here to thank everyone by name.

What didn’t turn up was a Mitsubishi-derived V40 or any representative of the 900 series, the ultimate evolution of the 700 series wagons, renamed in honor of its independent rear suspension and, in the case of the one we’d like to have seen, the 960, a straight-six motor. A much better car than it gets credit for, cursed by a short lifespan, its absence was noticed.

The 2017 V90 is svelte and comfortable as it leads its historic counterparts on a 2,000-mile road trip.

The final omission from our cavalcade of Volvos was the 145, the progenitor (1968-’74) of all the “boxes” to come, the cars that cemented the Volvo wagon thing by looking more or less the same for a quarter of a century, from the late ’60s until 1993. But divine providence intervened to correct an unconscionable oversight as we ran across a 145, a runner in only semimoderate dishabille, when we stopped at the Sub Rosa Bakery in Richmond, Virginia.

To ensure this crowd of Volvo volunteers wouldn’t go hungry on our station wagon sojourn, we brought along a couple of knowledgeable food professionals for dining tips along the way. Adam Sachs is the editor of Saveur and drives a V70. Jay Strell, a food communications strategist and fellow Brooklyn dweller, keeps a V50. Along for the ride and some light driving duty, they’d leave their own cars at home. Ditto my old friend, painter Fred Ingrams. He left his car—a too-slow-for-America V50 1.6-liter—at home in Norfolk, England, to come on a forced march to South Carolina as a passenger in a different Volvo wagon. He just hadn’t counted on it being 50 years old. Another drop-in from NYC, Jake Gouverneur, owns a Saab 9-5 wagon, but it has a blown head gasket and isn’t going anywhere.

There would, however, be no shotgun seat for Steve Ohlinger of The Auto Shop of Salisbury, Connecticut. A veteran independent Volvo mechanic, former racer, and (something tells me) former hippie, Steve brought his brown 1984 five-speed manual 245 Turbo, a rare bird. His role, to which he readily assented, was to carry The Knowledge and useful spares for when older pieces of Swedish iron fell in the line of interstate duty—except this happened not once.

Throw in a couple of Volvo PR honchos, a videographer in a V90 Cross Country, an event planner or two, plus our Automobile photographers, and there must have been 25 or more of us driving or riding along at any given moment. Teenaged me would have appreciated this concept.

Funny enough, no one ever did get an exact count on the number of participants. I later realized I was too busy driving to notice. Berkeley County, South Carolina, is a long way from Bergen County, northern New Jersey, especially in an 87-horsepower car with a pushrod engine geared to turn something like 3,800 rpm at 65 mph. The journey seems even longer and more sapping when it is conducted during a two-day rainstorm, with ’60s wipers clapping and a ’60s defroster fan hyperventilating while trying to keep up. But like all the old wagons on this trip, the 122S completed the journey without incident and no worse for the wear.

Swedish cream puff: This 1970s P1800ES “shooting brake” still cuts a stylish profile today.

Older models from the last century are one reason Volvo still has a good reputation to fall back on. Return solely to the early part of the 21st century for your wagon memories, and you’ll find Volvos with some major technical failings to answer for, cars that tarnished the company’s long-running longevity and reliability pitch. We definitely feel better about its new cars nowadays, but there is no predicting what age will bring.

On first acquaintance, though, we are impressed with just about everything to do with the black V90 T6 AWD R-Design wagon we’re driving here, though even in a fast, all-wheel-drive car we hoped for something better than the 26 mpg over some 2,000 mostly highway miles. There were undoubtedly economy-sapping power surges for which we were responsible, as there will always be with 316 hp turbo and supercharged 2.0-liter fours. But there were many more hours of economy-minded highway driving. Results closer to the EPA’s suggested 30 mpg (highway) are not too much to ask for.

The V90 looks great, and its leather-lined interior compares favorably to several Germanic alternatives. If nothing else, it’s airy and different. The car drives and rides especially well, with a nimbleness that belies its size. A little more than 16 feet long, it feels like a big, opulent car in the best sense but drives like a smaller one. Naturally, this executive-priced load hauler also comes with all of the tech and telematics features you expect. That is, expect to love, expect to regret, and one that still has us scratching our heads: Pilot Assist II, Volvo’s second-gen semi-autonomous driving system.

With $600 million of Volvo’s own money invested so far and $200 million in state incentives, Volvo expects to have spent $1 billion on the new factory and to have created 4,000 jobs here by 2030.

The latest Pilot Assist no longer requires you to track a lead vehicle, and it operates in self-driving mode at speeds up to 80 mph, which is nice. (Its predecessor topped out at a considerably less useful 32 mph.) But as “semi-autonomous” suggests, Pilot Assist II only steers for you for 18 seconds at a time, at which point a human must provide input, or the car will come gradually to a halt, which seemed dangerous to me. Another concern? The camera-based system orients the vehicle by using painted road lines on either side of the road.

Will the new V90 still be on public roads decades from now? If its forebears are any indication, the outlook is good.

As you might expect once you know how the system works, the car made large corrections following the white lines into corners, often steering later than we would have with more roll and general back and forth than an attentive, sober skipper would have allowed. Also failing to inspire confidence was the discovery that the V90 seemed willing to veer off the highway around bends where the white paint was worn off or pieces of roadway had fallen away, taking the white line with them. Last-minute driver intervention was most emphatically required. So, as with similar systems from other makers, you can’t fully rely on Pilot Assist II because you still can’t take your eyes off the road. It might make you wonder, beyond tech boasts and consumer beta testing, what is the exact point?

A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity.

Speaking of points, on the ride back to our hotel one night we got a chance to admire Ohlinger’s 245 Turbo in action. By action, I don’t mean heavy acceleration or drifting but merely having its headlamps turned on. That’s because they’re airport runway lights, an unlikely fitment the Volvo guru realized one day was a more or less straight swap, so he tried it, and guess what? They light up a road as if you plan to land a commercial jetliner on it, waking up everyone for miles and inducing post-traumatic stress syndrome in those unlucky enough to be in front of you when they suddenly catch your light show in their rearview mirror. We kind of liked it and made a mental note to look into the conversion. Although, as Ohlinger pointed out, “When they’re great, they’re great. But when they’re not, they’re really not.”

Bonding bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.

Bonding Bricks: No fewer than 60 years and 229 hp separate the V90 from the author’s 122S wagon. Both have their unique charms.The following day we headed to the factory site, about an hour’s drive, to inspect it from a distance while photographing all the participants in our station wagon safari. With the plant rising in the background, and the rain miraculously halted, it’s a rare photo that speaks to Volvo’s storied history and equally strong present. Carved here out of swampy woodlands, it represents a minimum investment of $600 million of Volvo’s own money and $200 million in state incentives. Volvo expects to have spent a billion dollars here by 2030 and to have created 4,000 jobs. Perhaps not what you thought of, old timer, when you saw your first 122S wagon all those years ago.

Like the wagons, I was in good shape when we arrived in Charleston for a late lunch. In fairness, however, I must admit I turned over the 122S on several occasions to other drivers while I enjoyed long stints behind the wheel of the V90. The newest, fanciest Volvo wagon yet seemed rocket-ship fast yet delightfully restful, one of the most comfortable rides going, with better seats than most all its modern competition much less those in the 122S, its ancestor from a half century ago. Lack of wind noise lends an amazing quietness to the V90’s cabin, too. Indeed Gouverneur, playing with a decibel-meter app on his phone, explained that the all-wheel-drive model was significantly quieter at 115 mph in the rain with wipers at full chat than the 122S was cruising at 65 mph with wipers off. I can’t speak to the accuracy of this because I was driving, and we all know I would never drive anywhere near that fast.

The Duett was built as a dual-purpose work and personal car and was the only body-on-frame passenger vehicle in Volvo’s U.S. lineup.

This magazine has long maintained that the station wagon format provides the most practical automotive solution for millions more Americans than are buying them now. We understand the auto industry passes time by chasing the latest styling fads, but after being rocked by the ungainly minivan and then crushed by the SUV and the hulking crossovers that followed, the once-best-selling wagon’s pendulum, which swung highest in the 1960s and 1970s, is long overdue to swing back. To the extent that logic plays any part in the matter, which is probably a dubious idea at best, the wagon is more efficient—lighter and more aerodynamic—than its crossover alternative. A wagon usually boasts the same or better interior space than its jacked-up relations and fraternal twins, and it probably handles better with its lower of center of gravity. Almost half the vehicles sold in Europe are wagons. Is life there so much different? We don’t think so.

Gimmicks and scarcity marketing are cool, I guess, but The whole idea presumes scarcity. And our trip to Volvo’s new plant proved the V90 wagon is way too good to be scarce.

Volvo has had success with sedans and even sports cars in America, but it is best known for its wagons, which are standard fixtures of the landscape in many American neighborhoods to this day. In a world of ever-changing automotive ideals, the Volvo wagon is a basic unit of automotive currency for many, the kind that spans generations. In my life, my parents drove a Volvo wagon, I drove them, my kids drove them, and with luck their kids might. Unlike some makers, Volvo’s never left the wagon field behind, and new proof in the form of the V90 warms the heart.

Yet recognizing fashion and catering to what it thinks most people think they want, the company has hastened in the 21st century to keep its lineup of crossovers and SUVs fresh, lively, and growing. Although there’s really nothing bad to say about the XC60, XC90, and upcoming XC40 models, we still prefer these platforms set up for wagon duty, pure and unadulterated. We don’t begrudge Volvo its high riders—they help pay the rent and the high taxes of super-socialist Sweden. We wish the V90, which shares its platform with the XC90, had as an option a third row of seats as does the SUV.

This affection for the wagon form generally and Volvo’s biggest wagon ever specifically is why we can’t help but second-guess the decision to soft sell the model, which is only available via internet order and not off the showroom floor. Dealers will receive as many of the Cross Country version of the V90 as they can afford to stock but no regular wagon V90s without an internet orde from Performance Junk Blogger 6 http://ift.tt/2yT2zt6 via IFTTT

0 notes