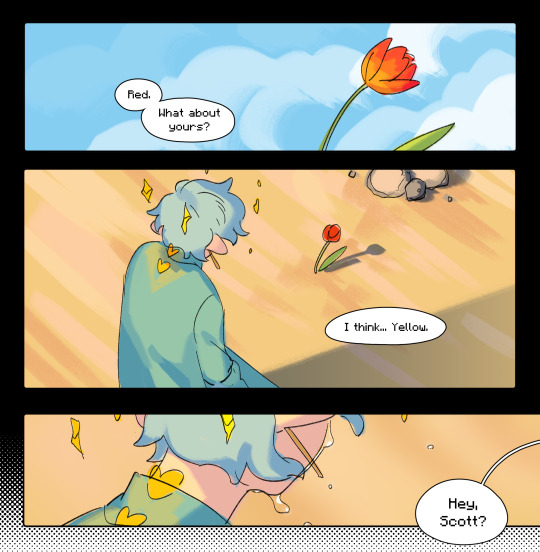

#they are the pinnacle of a couple doomed by the narrative

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

planning for the future

#please know that this was all written and thumbnailed in june#and i remembered it three days ago#and decided to finish it#anyways.#so flower husbands amirite#they are the pinnacle of a couple doomed by the narrative#they know each other through a hundred lives and only fall in love during the one where they can never have their happy ending#they still have an iron grip on me#as you can tell#scott smajor#jimmy solidarity#mcyt#traffic smp#trafficblr#comic#3rd life smp#life series#art#digital art#grian#gtwscar for like a single panel#also ignore all the inconsistencies this was all done from my memory of 3rd life#i know grian isnt in the bunker but i dont care enough to fix it#also literally just ignore any typos i beg of you#cw blood#cw corpse#cw death#long post

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

NEVER-ENDING PICTURES — The PASSING of ANDRIJA PIVČEVIC´ and the RESURRECTION of MARTINAC’ S HOUSE on the SAND

In a curious twist of fate, a great Croatian cinematographer, Andrija Pivčević (Gata near Omiš, 1945 – Split, 2019), passed away last year — same year when the most impressive feature film he had ever made—Ivan Martinac’s House on the Sand (Kuća na pijesku, 1985) — was restored and digitized, now ready to be shown. While Pivčević worked on many shorts for his colleague from Cine Club Split, the pinnacle of their collaboration is Martinac’s sole feature film, an impressive poetic achievement that the two men made together with film score composer Mirko Krstičević. The three Splitbased artists had conspired on set for the first time a few years before, in the film Exile (Izgnanstvo, 1979 –1981), produced by the professional film production company Marjan film—the same company that would be behind Martinac’s feature debut, as well as his three shorts to follow. Exile is an impressive 12-minute fiction film shot in colour by the ingenious Pivčević, directed, written and edited by Martinac himself, with Krstičević behind the inspirational experimental score, anticipating the topics and techniques used in House on the Sand.

Relying on two different expository levels, Martinac structures the film reality of Exile as a collection of subjective images from the mind of a young girl (Iskra Kovačević), at first dreaming, and then waking up and looking at a portrait of a man hanging directly opposite her bed, which the camera zooms on. The imaginary here, or rather scenes oneiric in nature, is evoked in/by the documentary shots of a boat on fire, as captured by Pivčević, exuding the seldom-seen audacity and impeccable sensibility for improvisation which are necessary to shoot the burning interiors of a doomed boat. There are also kinetic scenes shot from a moving car, perfect in their execution, following a motorcycle which the girl and the young man are driving on. In the scenes that follow, a girl is waking up and confronting the absence of her lover as illustrated in the conspicuous absence of the painted portrait. The film ends with a resurrection, with Arcadian views of Split all dressed up in snow, which marks the end of the spiritual journey framed with symbols of core elements—fire, air, earth and, finally, water.

Narrative-wise, the film functions as a metaphor for trying to capture what eludes us the most, that is, what we fail to approach, whereby the film even formally becomes set as in permanent exile. The camera is, at one point, trying to approach the flames eating away at the interiors of the shipwreck (i.e. a love-wreck), at another, it is zooming into the portrait of an absent lover (whose absence might be death by water, to use Eliot’s words) or chasing unattainable picture-perfect love with the help of tracking shots (as materialised in the scene with two young ones seated on the motorcycle); all of this, until it reaches its final destination—faced with the scene of the snow-covered city (in Joyce’s words, snow here is as mercy falling upon all the living and the dead). Exile is a film about the unattainable and its images, about a journey from love into death as the sole certainty. Its voluptuous visuals are among Pivčević’s most impressive feats, where the documentary segment of a boat burning is brought about with the same photographic confidence as the narrative chamber-like scenes of a sleeping, dreaming girl.

Several years later, Martinac returns to all of these preoccupations and techniques in House on the Sand, also graced with Pivčević’s impressive camerawork, which is impossible to miss, and Krstičević’s suggestive soundscapes, much like those from Alain Resnais’s documentaries from the 1950’s. The protagonist, a middle-aged archaeologist Josip Križanić, father of a girl, finds himself in spiritual exile after a divorce that he ends by suicide. Once again, we have a film structured as a vortex of images spurring from his mind, combined with scenes of his everyday life, so devoid of meaning. The pictures demonstrating the outsider lifestyle he leads are clear and raw, reduced to its ritualistic aspect, to mere gestures; while the ones representative of his inner world are in flux, dynamic and forceful to the eye. There are also scenes ‘in between’, marking the transition from one reality into another, in the form of long car drives. The masterful ending sequence is of particular note here; Pivčević keeps the focus on the reflection of a face in the car, when at one point the car enters the Split tunnel, and the urban scenery is replaced with an abstract play of light, evocative of a legendary light tunnel scene from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) by Stanley Kubrick. T he film is steered by impossibility — the impossibility of touch (no scene in the film shows direct physical contact), the impossibility of contact (the film keeps disrupting any meetings of the eyes, apart from one scene where the protagonist meets his daughter), as well as the impossibility of love as the ever elusive ideal which exists in material reality only as mere representation (zooming movement into the painting).

And while Pivčević zooms in — and quite masterfully so—on the Renaissance portrait of a young man in Exile (i.e. Titian’s Portrait of a Young Englishman), symbolising the lack of love in the female protagonist’s life, in House on the Sand, his focus is on the Renaissance portrait of the marital couple (Rembrandt’s Jewish Bride),which becomes an emblem of bliss missing from Josip Križanić’s marriage. In both cases, the camera is set on penetrating the absence as manifested in the presence of the Painting, treating it as a conundrum whose apparent verisimilitude is as a veil covering the real contents. Pivčević and Martinac mould the visuals as a mystery never to be solved, construed to arouse the viewer’s imagination and take the film beyond what is really present. The same technique is literally reflected in/on the filmed reality, which, in turn, these two deeply visionary films twist into endless anamorphoses, images intended to deceive, requiring of us to keep adjusting our field of vision, so as to uncover its secrets. I t was a curious twist of fate (which calls to mind Martinac’s first film from 1959, The Destiny, Sudbina) which made the death of a great man coincide with the resurrection of a film in which he re-shaped reality into a picture with no end, where the real boldly meets the imaginary. The restoration and digitization of House on the Sand was realised on the initiative of Martinac’s nephew, Ivan Vuković, helmed by Cine Club Split, and funded by the Croatian Audiovisual Centre. The challenging, long and complex restoration project of the film was personally supervised by Andrija Pivčević himself, who gave the green light to the final digital resurgence of House on the Sand, which will soon be available on the website www.ivanmartinac.com.

WRITTEN BY VIŠNJA VUKAŠINOVIĆ

TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BY MIRO FRAKIĆ

#Ivan Martinac#kuća na pijesku#House on the Sand#Andrija Pivčević#izgnanstvo#exile#Višnja Vukašinović#Miro Frakić

0 notes