#then its important to reframe it in its . original frame? of that being so dramatic and stupid.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

something really stupid that actually helps me with suicidal ideations is imagining the shit people would talk abt it. like in my head i kind of glamorize being some sort of tragedy, how wonderful itd be to be missed, so instead it helps to imagine people gossiping abt the theoretical suicide. like ill imagine my friends venting to Their friends, talking abt how shitty the circumstances of my suicide were for them. “we had ONE argument and he killed himself, what a fucking dick! always needed the last word” “he sent a note in the middle of the fucking night, dude i was literally jerking off and now youre DEAD, how am i supposed to jerk off now??” “he sent me a letter about his biggest secret, but if he had like..literally just told me one time ever, we couldve actually communicated about it, but noooo jack was allergic to communicating and thought DEATH was easier”

like this doesnt help with really bad episodes, but when its a thought that wont leave my head, it helps to frame it less as a hauntingly sad scene with a tearful goodbye and people throwing themselves at the sky, and more like. “god what an asshole. he did this over dishes”

#jack in OFF#ask to tag#IDKAY the classic But think of how your mother will miss you…doesnt work bc i feel awful abt it but i Want to be missed#but if i think of my mother like ‘oh my god he killed himself because he couldnt transition but literlaly all he had to do was wait like#five seconds for me to set up the court date for his name change’ its like Huh. Yeah that would be stupid#LIKE. JOKES ABT KILLING URSELF TO PROVE A POINT ARE FUNNY UNTIL YOUR BRAIN ACTUALLY WANTS TO START DOING THAT#then its important to reframe it in its . original frame? of that being so dramatic and stupid.

0 notes

Text

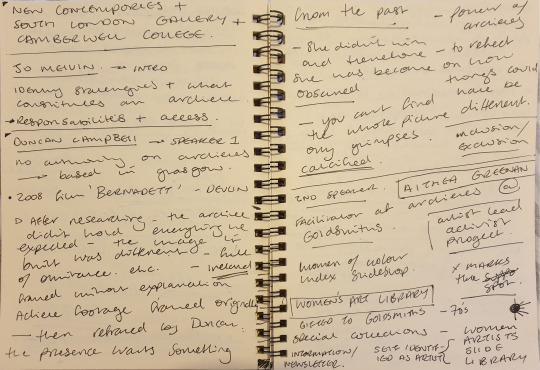

New Contemporaries: Archives & Identities - Part 1: Discussion Panel (03/03/21)

I signed up for two events hosted by New Contemporaries; the Archives & Identities Discussion Panel with Duncan Campbell, Althea Greenan, Sunil Gupta, and hosted by Jo Melvin on the 3rd of March , and the Sunil Gupta Workshop on the 4th of March.

(Screenshot from New Contemporaries Website)

I was drawn to these events as themes of archives and identities are ones that I think, even when my work isn’t explicitly dealing with, underpin much of the meaning of my work. The notion that we, as artists, are creating with our artwork archives for the future is one that to many queer and minority artists is really important; our archives often being limited as the archive is the legacy of the dominant culture. These were themes I dealt with heavily in my dissertation last trimester and Sunil Gupta is an artist who I did a considerable amount of research into while reading around the topic, so I was very interested in attending these events and learning more from his perspective.

The first event; the panel discussion was held via Zoom on the evening of the 3rd of March. IT was really interesting to hear the different artists present their perspectives on the use of archives within their work, and it made me reflect on the different forms an archive can take, and the different roles of archives within artistic practices.

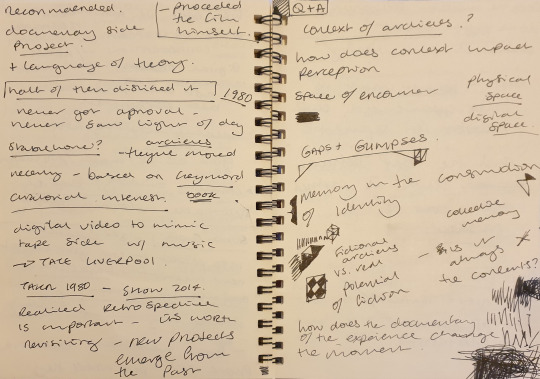

The first speaker Duncan Campell, winner of the 2014 Turner Prize, predominantly discussed his 2008 video piece Bernadett, a 40 minute exploration of the life of Irish dissident and political activist, Bernadette Devlin.

(Image from Duncan Campbell’s Bernadette, 2008)

It was really insightful to hear Campell speak on the process of producing this film and working with archive footage. He discussed the process of researching the archive and finding that it didn’t hold everything he expected; the image the archive has built through omittance was different to what he understood. He discussed the bias of archives; something that developed on the discussion of archives had by Danielle Braithwaite-Shirley and Ebun Sodipo in their artist talk together. He reflected on the way archival footage is framed in archives without explanation, and the fact that Devlin wasn’t the victor in her story, she was obscured in the archive. This reflection on inclusion and exclusion is something that I find really interesting- and hearing Campell discuss how he reflected this in his own work was really interesting; the process of reframing the footage for a present that wants something from the past.

He finished his discussion with a really thought provoking suggestion, that resonated with me and much of my own thinking about archives and how they record the past, saying that in the archive you can’t find the whole picture - only calcified glimpses. Reflecting on he archive, and why certain material gets preserved, who does the preservation, and what that material supports in its inclusion is something that I often explore within my own work and this notion that we are only afforded ‘calcified glimpses’ back to a past we long to connect to is one that I think is very pertinent.

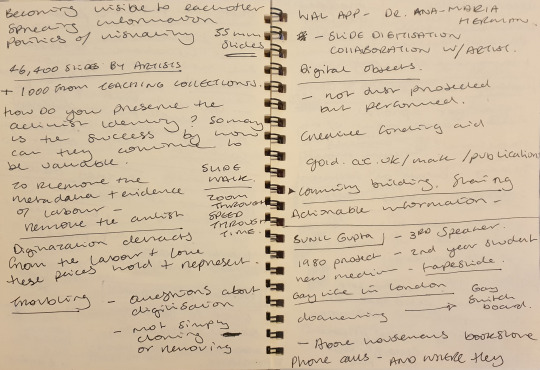

The second speaker, Dr Althea Greenan, is the facilitator of Archives at Goldsmiths, and she discussed the artistit lead activist project the Women’s Art Library which was gifted to Goldsmiths in the 1970s.

The Women’s Art library encouraged self-identifying female artists to document their artwork work; forming a collection of 46,400 35mm slides. Through this process of documenting and sharing, these artists were made visible to each other and able to spread information. This original college creates a huge archive of artwork by women, particularly women of colour, who in the 1970s, had much less opportunity to exhibit work and be conscious in the public eye. It is archives like this that reveal this critical - often otherwise undocumented - histories of people working in ways that do not uphold the values of the dominant culture.

(Image from Barbican Young Curators visit to the Women’s Art Library in 2019)

Greenan is particularly interested in preserving these archives, and how they continue to be valuable, particularly as technology becomes redundant. It was really interesting to hear Greenan discuss how she tackles presenting this archive while preserving the activist identity and integrity of it’s form. She reflects on the form of the documentation, the slides themselves with their metadata and evidence of labour, as being half of the archive themselves - more than just the images, and that to remove these components would be to remove the artist; directly contradicting the archive’s original purpose.

She argues that the process of digitization detracts from the labour and love these pieces hold and represent- yet keeping the archive hidden away in boxes at Goldsmiths too, is keeping the archive from serving its purpose as a legacy of the creativity of often subjugated women. I think this conversation is particularly interesting in this context; where the archive in discussion is predominantly a working class, black women’s archive, and now it is only made accessible within Goldsmiths; an institution, which therefore is subject to institutional issues of racism and structural discrimination.

She discussed the various ways she had explored this process of making the archive available without sacrificing it’s integrity, through presentations, certain digital documentations; not just projecting the artwork but performing it- the slides being preserved not just as images but digital objects.

Overall I thought this was a really interesting discussion about the purpose and legacies of archives, and what happens to them when the technology they are recorded with becomes redundant.

Sunil Gupta spoke next, discussing in particular his work with the Gay Switchboard which until recently hasn’t been publicly presented.

The Gay Switchboard began above Housemans bookshop near Kings Cross in 1974, and served a resource for LGBTQ+ individuals after coming out, and as a way of locating safe spaces, developing in the 80s into a critical resource for the dissemination of information surrounding HIV and AIDS.

vimeo

As a student in 1980, Gupta spent time documenting the work of the Gay Switchboard and wider ‘scene’ in London that the switchboard connected callers too. This work was presented as a tape-slide work with audio, and upon showing the Switchboard their material, it did not receive approval and it was shelved. Recently however there has been curatorial interest in the work, and the work was shown in 2014 at Tate Liverpool as part of Keywords: Art, Culture and Society in 1980s Britain.

This raises interesting questions about the importance and legacy of archives, while at the time the value of Gupta’s work couldn’t be fully realized- this archive of gay life in th early 1980s is extremely valuble now that images and documentation of LGBTQ+ lives in the 1980s are predominantly concerned with the AIDS crisis or otherwise lacking.

In the Q&A portion of the panel, discussion predominantly turned to ‘gaps & glimpses’, with the panelists discussing the context in which archives are consumed and how this impacts the perception of them. The discussion was really insightful, considering the nuance of documentation, the process of fictionalising and the potential of fiction, as well as the way gaps in archives inform the archives themselves.

I left the discussion thinking about the positive potential of archives and their pull, as well as reflecting on the archives we create now - we all document so much of our lives each day online- in many ways our art instagrams serve the same purpose as the Women’s Art Library - and presumably one day, instagram too with be defunct and what will happen then to the archives created and shared there. Furthermore, the pandemic has shown us firsthand the way things can dramatically change in the blink of an eye- and now, looking back at photographs of nights out, clubbing, crowds of people, even just being in the studios with friends, these serve as an archive and a portal of something we can currently no longer access- these documents now having a weight and a purpose that couldn’t have been predicted.

https://www.newcontemporaries.org.uk/exhibitions-and-events/events/-archives-identities-panel-discussion https://www.newcontemporaries.org.uk/current/archives-identities-workshops#:~:text=Archives%20%26%20Identities%20is%20an%20online,arts%20practice%20to%20explore%20identities. https://www.southlondongallery.org/events/archives-identities-workshops/ https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/dec/01/turner-prize-2014-duncan-campbell-wins https://lux.org.uk/work/bernadette https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/duncan-campbell-12393 https://www.gold.ac.uk/make/artistsdocs/ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/10/goldsmiths-university-to-tackle-racism-after-damning-report https://www.gold.ac.uk/make/collection/ https://switchboard.lgbt/about-us/ https://muse.jhu.edu/article/777711 https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-liverpool/exhibition/keywords-art-culture-and-society-1980s-britain

1 note

·

View note

Text

Here we are, the penultimate episode, and I’m already a little sad. As much as I’m going to miss this surprisingly loveable little show, I think I might miss our after reviewing tradition even more. OK maybe not more, it really is a very sweet show, but just as much!

It’s been great! I hope you’ve felt as creatively free as I have!

Crow (crowsworldofanime.com) and I have been pretty united in out praise of Zombieland Saga so far but this was an odd episode. Let’s see if the trend can stay true to the end. Not that I’m teaching you guys anything but Crow is bold man.

Well, bold-ish…

this is meta, why is Zombieland showing me watching the show?

Straight off the bat, this episode was a bit of a gamble for Zombieland. Not that it’s unusual to have the before last episode take a tonal turn, it’s actually fairly common. However, this week’s Zombieland wasn’t only uncharacteristically sober, it reframed the main character into something that may not be as likable to the core audience. Effectively throwing out a lot of character clichés and even robbing Sakura of any real redemption arc. Any feelings about the narrative shuffle?

You’ve honed in on exactly the part of the episode that left me feeling uneasy — at least, emotionally jolted. Sakura’s despair and self-reproach are almost too familiar! And at the same time, those apparent failures in her life, and her reaction to them, robbed her of the ability to understand something important: That she really helped those old ladies. That she really had friends who rooted for her. The insight changed how we have to interpret the entire Sakura arc, and it also raises an important psychological “what if…” But let’s leave that for later.

sort of…

As soon as the episode started I got excited. Last week’s cliffhanger was one of the best I’ve seen in a while and I couldn’t wait to see how they were going to resolve it with so little time left. I never expected them to play it straight. Although, I’m not sure what I expected at all.

You and me both! The show’s conditioned me to expect subtle irreverence at every turn, but this time, they plowed straight ahead.

Sakura has lost her memories of being a zombie but remembers her life. Which turns out to be frustrating and unsatisfying. Moreover, her traumatic death is just the last straw in what she considers an utter failure of a life. Completely demoralized, Sakura more or less shuts down, and pushes everyone and everything else away.

she’s pretty much always like this

The opening scenes, with Sakura freaking out over the zombies, were a nice way to call back to episode 1 and bookend the series though. Even the visuals were parallel.

And, of course, she just had to meet Tae first! And Tae has such a gentle way of saying “Good morning!”

Saki looked so worried about Sakura and it was adorable!

All of their reactions were just heartbreaking!

agreed

I must say, that was an impressively down to earth portrayal of depression. It was a bit obvious, although I’m not sure they could have done otherwise considering the time constraints, but it was also unflinching. There was something weirdly admirable about Zombieland’s resolve to not just let Sakura magically snap out of it.

That’s another aspect that left me feeling so unsettled — and I don’t mean that in a bad way. It was too spot on. But given who Sakura is, and given what this show’s presented so far, I can think of only a handful of other shows that could trigger this kind of reaction.

this framing is brilliant

Equally laudable, in my opinion, was the grim repercussions on Saki, Junko and Lily who attempted to help.These situations don’t just affect one person, they affect everyone around as well. And they affected them all in different ways. This was far from a flattering depiction of Sakura but sometimes, when you fall far enough, you just don’t have the strength to empathise anymore.

I couldn’t believe how bad I felt for the others as they tried to help her! Especially Saki and poor Lily! For Lily to go from “Before you said you thought that star and my smile were cute!” to sobbing uncontrollably into her pillow drove home a critical point: That until now, these zombie idols have supported each other; and now that one of those pillars of support is crumbling, all of them are in turmoil.

and the repetition makes it truly special

Once again, Zombieland Saga is tackling a fairly serious and not at all funny subject openly and resisting the urge to turn it into farce. I really didn’t expect any of this when I started the show!

I remember the old M*A*S*H series. Great comedy for its time, but because of the comedic expectations, it had an opportunity to make powerfully dramatic points — as long as they didn’t do it too often. I get that vibe from this show!

You know what, I see it now. I loved M*A*S*H (use to watch reruns with my folks). That cutting sensibility is very much like Zombieland!

most of us feel this way

After having hurt the people closest to her (and having them retreat helpless, not knowing what to do), Sakura just aimlessly wanders the night ending up in a park.

Here we see the return of the creepy police officer. He didn’t really have much to do other than once again instill the feeling of déjà vue. But just like everything else this week, the familiar scene played out completely differently. The downtrodden and hurt Sakura was almost pleading to be shot. A sort of balm to her intangible pain. The entire thing was extremely unsettling and yet, oddly pretty.

I remember thinking it was tragically beautiful.

this scene was delicae, poignant and solemnly meaningful…

I should have realized it sooner of course. Sakura has always been a bit helpless after all. I should have seen that she was being set up as a damsel in distress. Still, such an unusual distress for anime.

In the end though, Sakura at her worst, brought our Kotarou at his best. Manager made his glorious entrance in the nick of time. Knocking out the cop (that poor guy has to have some long term brain damage by now) and swooping in to save the day.

Maybe that’s why he’s so creepy? One (or ten) too many blows to the head?

he’s had a few shocks

Manager has never been that great with words. It’s part of the gag. And although Zombieland played the scene seriously, he still wasn’t exactly inspiring. Sakura was more confused than motivated. This said, there was enough feeling, care and passion behind his words to at least give her something to latch onto!

May favourite line of dialogue was manager exclaiming “It doesn’t matter if you don’t have it, because I do!” The I’m good enough to make you good pep talk is not what we usually hear and I loved it. Would have worked on me! How about you?

It would have been so unexpected that it’d have a good chance at loosening my defenses. And did you catch how the show played with the trope of the voice of reason (the manager, in this case) storming off to let the main character wallow in a miserable soliloquy? Just as Sakura is descending into a self-loathing speech, Koutarou startles her with “Yeah, you thought I was done, huh?” Loved it. This show knows how to teeter right on the edge of melodrama!

surprisingly, that might be true

One of the few straight up jokes in this episode, was Yuguri dressing up in full geisha get up, and looking mightily impressive I might add, just to realize Sakura’s already left. I really would have loved to see Yuuri in that outfit longer. Any thoughts?

My first thought was the typical male response. I mean, Good Lord, she looked amazing! But then I had this sudden chill and realized that Yuguri had slapped before, and she could slap again! I was in fear for Sakura’s face!

I’m not thinking about anyone else’s face

This episode brought up a fascinating question: Just how profound an impact do our life experiences have on our hopes? In Sakura’s case, she weathered a seriously frustrating series of events. From an operant conditioning perspective alone, I can understand her reaction! But to be running out of the house, all excited to be back on track, and get killed? Jeesh!

But in her case, and apparently in her case alone, her amnesia was a complete blessing.

I still can’t get the image if Lily sobbing into her pillow out of my head. All of them are standing on such thin ice…

Saki is all of us

For me it was Saki. Frustrated, lost and a little scared Saki. First time we are seeing hr shaken up. If Saki can’t just make it all better and shrug it off, what are we going to do?

Seeing her check her thumb nail was such a perfect way to show her pain.

[ Did you want to mention anything about Koutarou’s conversation in the bar? In the comments on the ZLS 11 review on Random Curiosity, https://randomc.net/2018/12/13/zombieland-saga-11/, users Nene and Panino Manino had some really interesting theories…

This was a difficult episode to watch — and to review! Thanks for setting up the frame! ]

risk it, it’s worth it

Guys, this little bracketed text is in fact just meant for me. I’m leaving it in. I like seeing behind the curtain stuff on posts so I think you guys might enjoy it too. I also really like that Crow pays attention to his fellow bloggers and readers. He often points out comments or posts I have missed and I am very much richer for it.

You should go read Nene and Panino’s theories.I unfortunately don’t know enough to add anything interesting.

This said, manager’s bar scene was very intriguing. I didn’t originally comment on it in the post proper because I had so many things to get to, I didn’t want to overcrowd it but you know what – clarity has never been my brand.

flashback scene without warning or context!

There’s a reason your blog’s so popular! (dawwww)

These are my random takeaways from that scene. The village of Saga itself is responsible for the zombie phenomenon in some way, and Koutarou is not the only one who knows. He also plans to make it public at some point.

Koutarou himself has been around for a while. Since it’s very reasonable to think that he’s also not quite human, he could be hundreds of years old for all we know. This may be one of dozens of attempts to save Saga.

Maybe that’s why Saga’s still there at all?

this took a turn

The bartender seemed to have a very close personal relationship with Yuguri. Considering the family theme so far, I’m tempted to say he’s her dad.

Yuguri is a courtesan, which implies a lot of things. Although she is certainly charming and imposing, she has so far avoided being openly seductive or sexual. This could simply be because of the tone of the series but it may also have something to do with her life. Did she leave someone important behind?

I’m still wondering about the scar around her neck!

what do you mean just one episode left?

There cannot just be one episode left. We have so very much to explore still!

I’ll second that. It seems like this season has just given us a brief glimpse into a zombie world that’s coexisted with the human world — apparently for hundreds of years! Are there other zombies out and about? It seems they’ve kept themselves private, but I think you’re right when you say Koutarou wants to make it public — why else do something as obvious as an idol group?

And I’m just not ready to say goodbye to Franchouchou!

Despite using do many in the post, I actually still have a few screencaps left. I hope you enjoy them. This week was great for caps.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Irina and Crow in Zombieland (Saga) ep11: It’s Always Darkest Before the Dawn Here we are, the penultimate episode, and I’m already a little sad. As much as I’m going to miss this surprisingly loveable little show, I think I might miss our after reviewing tradition even more.

0 notes

Link

THE 19TH CENTURY, violent and progressive and anxious and confident all at once, seems to be getting closer to us the further it recedes into the past. Many of the defining characteristics of the age, roughly bracketed in Europe and the United States by the French Revolution and World War I, are no longer so foreign. We, too, know what accelerated technological change feels like, how it can rearrange the experience of reality and unsettle the future of work. We have our own callous oligarchs and grotesque inequalities. We are readjusting to the geopolitical jockeying of rival powers, to the brittleness of our inherited structures for international peace. Like the men and women of the 19th century, we can sense that our world is both hyper-connected and coming apart at the seams. In 1895, Oscar Wilde skewered his own paradoxical century as “an age of surfaces” in which a veneer of rationalist optimism concealed subcutaneous truths: hypocrisy, suffering, cruelty, resentment.

Holly Case, an associate professor of history at Brown University, has wagered on the surfaces. Her ingenious and often demanding new book, The Age of Questions, is concerned less with the century’s lived experience and more with the language used by its leaders to understand and change it. The thorniest challenges, she shrewdly observes, were often framed as questions. The “social question” pondered the status of the working poor, how to soften their misery and either prevent — or provoke — a revolution. The “Jewish question” assessed the possibility of assimilation or integration. The “Eastern question” was frequently shorthand for the gradual disintegration of the Ottoman Empire. Debated by prime ministers and pamphleteers alike, questions were a widespread tool for structuring problems, from strategic puzzles and social upheaval to literary arguments (the Shakespeare question), professional regulations (the dentist question), and much else. “[A]ll the most important questions of Europe and humankind in our day are forever being raised simultaneously,” Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky commented in 1877. The conundrum, he continued, was to figure out precisely when and why all these questions had exploded onto the scene.

Taking up Dostoyevsky’s riddle, Case has produced a path-breaking account of the question form: its spectacular rise in the 1830s, its fall from grace after World War II, and (she hints) its possible resurrection in our own time. Roving and ambitious, with an unusual literary-philosophical sensibility, the book itself recalls the 19th century. And the full title is positively dizzying: The Age of Questions: Or, A First Attempt at an Aggregate History of the Eastern, Social, Woman, American, Jewish, Polish, Bullion, Tuberculosis, and Many Other Questions Over the Nineteenth Century, and Beyond. Joining erudition with a poetic if occasionally enigmatic style, this book shivers with the restless spirit of the age it describes.

The great queries of the 19th century resonate still. It was by framing issues as questions, after all, that men and women went about resolving the essential problem of modern politics: how to convert thought into action, bridging the gap between reality and ideals. But questions also whisper of a lost world. At the heart of this story lies the conviction — held by the leading lights of the period no less than Case herself — that political language matters, that the words we use to interpret the world are markers of possibility for finally changing it. That, in short, the frame of things defines our vision. Whether or not this remains true for a postmodern age of information overload, industrial-strength deceit, and atrophied political imagination is a question for us to answer.

¤

In the beginning was the American question. In the 1770s, as the inhabitants of the 13 Colonies clamored to be heard in London, British politicians began thinking about the problem as a query. Edmund Burke called the tensions “American questions” in a 1774 address to Parliament. Before long, parliamentarians and journalists were widely invoking “the grand American question” and “the question of sovereignty over America.” That question was answered by revolution and independence. Next came the bullion and India questions, parliamentary discussions over currency depreciation and the expanding authority of the British East India Company. The question form, then, first arrived as a peculiar kind of legislative convention — a formulaic way for British politicians to confront opponents, organize debates, and make decisions.

By the 1830s, questions had broken away from their British origins to shape political issues across the European continent. Suddenly, men and women from Paris to Moscow were discussing questions Belgian and Jewish and Polish and maritime, Algerian and Eastern and labor and Greek. And they were doing so within the parameters of a new global public sphere that made such transnational arguments possible. After the final defeat of Napoleon’s armies in 1815, European statesmen sought to guarantee order through diplomacy and cooperation — a system known as the Concert of Europe. Together with the expansion of periodicals and the press, the slow strengthening of parliaments and voting rights, and a rapid-fire sequence of startling international incidents, most of all revolutions in France, Belgium, and Greece, an arena emerged for which the question form was particularly well suited.

After all, the great questions of the 19th century were not genuine inquiries. They were not open-ended explorations seeking knowledge and truth. They were weapons. To reframe a complex issue as a question was a powerful way to define the terms of debate, foreclose alternatives, and advance a preferred course of action. As Marx succinctly put it, “the formulation of a question is its solution.” Regarding the Eastern question, pulpy German novelist Karl May noted in 1882 that “whoever can first define it gets to solve it.” Much like the -gate suffix does today, questions instantly organized the public’s understanding of a problem. Rather than implying scandals or cover-ups, however, questions told confident stories about how even the most overwhelming dilemmas might be analyzed, understood, and resolved. Questions were tools of progress. Those who posed them, Case says, “were prophets with one foot in the present and another in some imagined future.”

As the century drew to a close, questions gradually lost their force and urgency. But they returned with a vengeance after World War I and the Versailles peace settlement, when the undoing of empires and redrawing of borders made dramatic change seem once again possible, even desirable. Nobody was better at putting them to work than Adolf Hitler, the cruel yet natural heir to the long age of questions. That the Third Reich sought a Final Solution to the Jewish question is well known. But the Nazis also provoked a cluster of new territorial and ethnic problems as they consolidated power, each one framed (as Case astutely notes) as a question to be solved: the Saar question, the Austrian question, the Danzig question, the Sudeten-German question. Hitler argued that German greatness hinged on their simultaneous resolution. “Each of us will pass,” he said in 1933, “but Germany must live, and in order for her to live all questions of the day must be overridden and certain pre-conditions established.”

Throughout their lifespan, questions were effective devices for those determined to bring about revolutionary change. They helpfully translated the complexities of human life into simple problems to be clinically and rationally resolved. It is perhaps not all that surprising that they came to serve the megalomaniacs of the 20th century — or that the question form was so definitively forgotten after the Holocaust. “[T]he path to war and mass violence was paved with questions,” Case concludes. “The Final Solution was no perverse coda to the age of questions but rather its fullest realization.”

¤

From the 1770s to the 1970s, questions lived mostly in pamphlets and treaty negotiations and speeches and debates. That’s where Case has gone to find them, exhaustively digging through the archives of 11 countries and sources in 16 different languages. This is research of staggering breadth, certainly of a piece with the sprawling, interconnected 19th century. But this enormous scope seems necessary for the question form, too, a species of political language distinguished by especially great hubris and ambition during what was already, as Eric Hobsbawm wrote, “an age of superlatives.” And the longer certain questions lingered, the more universal and grandiose the solutions became. Intractable issues like European cooperation or the status of ethnic minorities appeared to demand not minor adjustments but rather the violent creation of a completely new world.

Reconstructing the vast question economy is a breathtaking scholarly feat, though it sharpens the contours of the 19th century more than it redraws them entirely. The question form ascended because it was brisk and snappy and able to generate headlines in a world choked with information. But it also appears to have tapped into deeper currents. Questions channeled not a particular political ideology so much as the spirit of the times — a rationalist, scientific, often masculine sensibility that ruled the century with confidence and a belief in progress. “With a little patience and attention,” noted one representative figure in 1865, writing on the Hungarian question, “everything that can be known […] can be simplified and solved.” Driven by quiet arrogance, questions wondered what was to be done about a given problem; it was assumed both that a solution existed and that those posing the query were, naturally, the ones to bring it about. This bourgeois sensibility, the engine of the century’s breakneck technological and industrial development, must be part of what made questions so authoritative. They are what it sounds like when power speaks.

Has the question form returned? Case suggests that maybe it has, detecting among recent geopolitical events a growing tendency to frame complex problems as queries. She finds Vladimir Putin discussing “the Ukrainian question” as well as journalists and critics analyzing the English, Irish, Scottish, Catalonian, and migrant questions. We might add the Russian question to this list. “Could it be that we are now on the cusp of another age of questions?” Case wonders. “Is it indeed part of the past, or are we still living in it?”

If the magic of questions lies in the form itself, this may be so. But it is difficult to read Case’s brilliant account and not sense that it is really about a certain kind of political imagination — one that we have mostly lost, for better and for worse. As citizens at least, we have generally turned away from the world-making assurance that shaped the age of questions. We know more than ever how our problems are inextricably tangled and interrelated, how our decisions affect the planet and each other. And our political cultures have been scarred by the violent totalitarian projects of the 20th century no less than by the constricting force of neoliberalism. We have generally come to favor tweaks and fixes over transformative, paradigm-breaking political change.

There are notable exceptions to this humbling of our imaginations, from the brash, disruptive faith of Silicon Valley to the burn-it-down bravado of the American right. For the most part, however, we have come to meet our political challenges with less certainty than our 19th-century forebears. Tracing the history of questions, then, is more than an exercise in form. It is an opportunity for us to hold our own political sensibilities up to the light and think anew about what it means to have the confidence to change the world.

¤

Ian P. Beacock is a historian of modern Europe and PhD candidate at Stanford University. His essays and reviews have appeared in The Atlantic, the New Republic, and elsewhere.

The post The Frame of Things appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2x4FeFU via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Your Truth, My Truth And The Truth

Charlie Woods

The story of the blindfolded men who each approach an elephant from different angles (at the tusk it’s described as a spear, at the tail a rope, at the leg a tree etc.) is a good example of how multiple truths can exist depending on the perspective you take. Different views can often be the starting point for disagreements. Mix in a few cognitive biases and things can quickly escalate. For example, as evidence is sought to back up an initial conclusion (confirmation bias) and the behaviour of others is interpreted to be a reflection of their underlying character, regardless of context (attribution error).

Cognitive biases are all around us and are entirely normal, they are a key feature of our evolutionary make up and were critical to our survival when energy was at a premium, danger was all around and being able to trust close neighbours was vital. Because they speed up our decision-making in the not so distant past they could often be the difference between life and death.

As the environment in which we live is now dramatically different from the one in which we evolved it is important that we develop a fuller understanding of how these biases might be influencing our understanding of events and our decision making. Psychologist, Daniel Kahneman in his book ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’, provides the most comprehensive exposition of the role that cognitive bias can play. Along with his colleague Amos Tversky, Kahneman identified many of the most influential biases. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for economics for the insights this work gave to how people make decisions in practice.

At the recent CIArb annual mediation symposium in London Ken Cloke and John Sturrock discussed some of the biases that can have most influence on conflict and its resolution, they included:

• Availability heuristic: The tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events with greater “availability” in memory – influenced by how recent the memories are or how unusual or emotionally charged they may be. • Anchoring: The tendency to rely too heavily, or “anchor”, on one trait or piece of information when making decisions (usually the first piece of information acquired on that subject). • Belief revision: The tendency to revise one’s belief insufficiently when presented with new evidence. • Empathy gap: The tendency to underestimate the influence or strength of feelings, in either oneself or others. • Endowment effect: People ascribe more value to things just because they own them. • Framing effect: Drawing different conclusions from the same information, depending on how that information is presented. • Loss Aversion: The pain of loss is greater than the pleasure from gain. • Over optimism / over estimating own ability: often experienced by advisers. • Priming: Exposure to one stimulus influences response to another stimulus. • Reactive devaluation /overvaluation: De/over-valuing proposals only because they purportedly originated with an adversary.

These are just the tip of the iceberg and they give a flavour of the influence bias can play.

In many ways the process of mediation offers the opportunity to engage the ‘slow’, energy intensive, thinking that is more rational and is needed to counter some of the biases resulting from ‘fast’ thinking. It can allow parties to a dispute to better understand issues and how they look from different perspectives, it offers the chance to bring the different perspectives to bear to try to explore options to increase the size of the pie before trying to divide it and it can help reality test possible ways forward.

The role and skills of the mediator in the process are critical as well. Ken offered a number of helpful examples of what can be done to both build on and address biases, these included:

• Create an environment with objects that “prime” or encourage collaboration and dialogue. • Slow, soften and relax your tone of voice, and create a context of acknowledgement and appreciation. • Listen closely to the words they use and search for ways of reframing them from negative to positive. • Use words that emphasize the outcomes you want to achieve, like “fair” or “satisfying” or “creative.” Try to avoid words like “tough” or “win” or “dissatisfied” or “hard”. • Seek unilateral, unexpected concessions from the parties.

By their very nature, cognitive biases will always be with us and thinking fast often serves us well. The more we’re aware of the downsides, the more we can be on guard for when they might be getting in the way and when it might be time to slow down.

More from our authors:

EU Mediation Law Handbook: Regulatory Robustness Ratings for Mediation Regimes by Nadja Alexander, Sabine Walsh, Martin Svatos (eds.) € 195 Essays on Mediation: Dealing with Disputes in the 21st Century by Ian Macduff (ed.) € 160.00

The post Your Truth, My Truth And The Truth appeared first on Kluwer Mediation Blog.

from Updates By Suzanne http://mediationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/2017/10/03/truth-truth-truth/

0 notes

Text

‘The Man That Got Away’ number in the 1954 version of A Star is Born directed by George Cukor is widely acknowledged as one of the very greatest in the history of the musical genre. There’s so much to admire: dramatically, the choice of a song of loss and longing as the moment that sparks admiration and love in the narrative is inspired — it’s at first unusual and original and later becomes prescient and structuring. The song itself, a Harold Arlen and Ira Gershwin tune, written for Garland, given a great brassy orchestration by Skip Martin, and so great it’s become a standard covered by practically everyone including a sparse version by Jeff Buckley accompanied only on guitar. Garland’s performance of the song, both the singing and the acting of it, are, as I will demonstrate later to any who doubt, legendary and beyond compare. As is the choice to film it as a noir in colour with most of the colour drained out and used sparingly but powerfully. Here director George Cukor acknowledges the contributions of production designer Gene Allen and legendary photographer George Hoyningen-Huene to the way the film looks. Sam Leavitt was Director of Photography.

What I want to deal with here is the direction, particularly in its use of the cinemascope frame: the fluid arrangement and re-arrangement of compositions, the forward move of the action, the creation of the illusion of three dimensional space and the way which the filmmakers manage to create a sense of horizon in a narrow rectangular frame. CinemaScope was relatively new then and, along with technicolour, prominently publicised in all the posters for the initial release. This number to me is a sublime example of brilliant use of it made even more gobsmacking by the singing of the number all being filmed in one shot.

If you’re interested have a look at the number, refresh your memory. delight in the brilliance of the singing, the acting, the direction, the look, the way the scene unfolds and the way the camera moves…

Shot 1 (14 seconds): Then let’s look at the first shot of the sequence. Note how the frame is divided into thirds, that the title of the club is the ‘bleu bleu’ — significantly narratively as a place one goes to drown one’s sorrows but ends driving the blues away and also as an indicator of the overall look and tone of the scene — advertised on different sides of James Mason’s back (see the first frame.) Then Mason advances towards the door, whilst the camera at first stays still, thus creating a new composition within the shot, now we have neon blue on one side, and a poster, pinkish with red overtones, advertising the band on the other. In the third reframing within the same shot, the camera has caught up with Norman Maine (James Mason) and as he opens the door to the club, the door occupies one third, the poster the other and Maine and the open door roughly occupy the centre. The open door gives a sense of horizon, the illusion of three-dimensional space so familiar from Renaissance painting, think of the Mona Lisa, and so hard to achieve in that narrowly rectangular cinemascope frame. The door opening coincides with the brass element of the orchestration trumpeting the refrain: something new is announced, a new space of possibility just beyond the horizon.

Shot 2 (3 seconds, see frame enlargement below): the second shot is only three seconds. It’s an establishing shot of Norman Maine looking. But note how the shot is almost drained of colour except for the neon red throwing its pool of light from outside to the inside of the club. Note also how the lighting is focussed on Norman Maine’s face, and how the furniture is arranged along with the post in the right hand side. This creates a triangular shape within the frame, a sense of horizon, this time from the reverse perspective that we saw in the previous shot and inside. What the shot establishes is Norman Maine’s point-of-view, which is what will anchor the whole sequence. His gaze on her is what’s important, it’s how she, through him, will demonstrate to us that she is in fact the great singer and star he will know her to be once the song ends and that we the audience, already know. According to Patrick MacGilligan,

‘The marriage of Technicolor and the wide-screen CinemaScope (a process still in its infancy) was partly responsible for the delay and cost. Color-test scenes had been filmed and re-filmed until everyone was satisfied’ (p.226). One can see in this shot how all those tests with the format and the colour paid off. It’s sparse, elegant, dramatic, like the work of a great painter, or here a great director elegantly mobilising all the talents of his cast and crew to purposeful and meaningful expression that delights the eyes and ears.

Shot 3 (7 seconds, see frame enlargement below)

The third shot is Norman’s point-of-view. He looks in the previous shot and this is what he and we see. Note how Esther Blodgett, soon to be transformed into Vicky Lester, superstar, and played by Judy Garland is a pinprick in a pool of light at the centre of the frame with her band. Her importance is signalled by her centrality but not quite yet made overt. Note how the frame is also divided into thirds. How the chairs on the right are closer to the lens, how the two musicians are framed by that pink/coral light we first saw on the poster on the right side of the frame in the first shot, accented by the pool of light that follows Norman Maine’s entrance into the club in the second shot. Note how this arrangement helps create a sense of three-dimensionality, gives a horizon to the space that would otherwise seem flat. Note how there’ a sense of drama in placing those chairs so as to impede but not quite block our view of Esther and the band. She, and her talent, will only fully be revealed to us later. It’s not only gorgeous and artful but dramatic and meaningful.

Shot 4: (23 second, see frame enlargements below)

The fourth shot is a plan sequence, a longer take, which can have different sequences within it created by camera movement and which involves the orchestration of various elements. This shot begins where shot 3 left off (see frame enlargement below on the left), with Norman Maine at the entrance of the club, triangularly placed on the horizon, with that hint of neon red just above him. He moves towards the camera, which is towards the sound of the band, towards Esther, and through pools of light and darkness. As he sits on by the pile of chairs, a waiter enters the frame from the left (see frame enlargement below, centre). At this point the camera leaves Norman and accompanies the waiter through the club, past chairs and pillars (John Ford claimed that nothing created a sense of three dimensionality as moving the camera past trees. This has a similar effect) to deposit his tray by the band (see frame enlargement on the right). The touch neon red behind Norman Maine has become the quasi coral pink that engulfs Esther Blodgett and her band, and her face is bathed in pure white light. The dramatic advantage of filming it in this way is that Norman and Esther are united in space and time, that his attention is focussed on her, he is watching she is doing performing. Symbolically his darkness, his troubled moving through dark and light ends with a hope of pure light in a coral setting. How better to represent was Esther/Vicky will represent to Norman?

Shot 5 (4 seconds)

The fifth shot is a closer look, Norman Maine’s look, on where the camera had deposited us previously. ‘Take it honey’ says the pianist. Esther rises as you can see below, occupying the left third of the frame. As the pianist reiterates ‘Take it from the top’, Esther will come to occupy the right of the third of the frame, so in one shot there’s an elegant move across the wide Cinemascope frame, from left to right, once more leaving the frame neatly organised in thirds, whilst the pianist, chiars and glasses behind the bar, all work together to create an illusion of depth.

Shot 6 (1 second):

Shot six barely lasts a second. It’s a medium closeup of Norman Maine straining to see through the darkness of the empty club. The editing here reminding us that it is Norman who is looking, like us, but unlike us, and as was established in shot four, Norman and Esther are united in time in space. We’re reminded of us as the voice-over to this shot is Esther repeating what the pianist had said but as a question ‘from the top?’. The sound is Esther, the image is Norman. He is the big star, she is the unknown band singer yet it is he who is looking, she who is being looked at.

Shot 7: (3.26 seconds. The frame enlargements below are representative examples of each time the camera moves and re-calibrates the composition, except for figures Gand H which are the same composition but where Esther commands the image, the arrangement of things and figures in the frame created in the ‘good riddance, goodbye moment’ with a wave of her hand on the goodbye moment which makes all the musicians bring down their instruments)

Every re-framing of ‘The Man That Got Away Moment’ can be analysed in at least as much detail as the shots discussed previously, which themselves can be discussed in greater detail than I’ve offered. I characteristically have run out of time just at the moment of greater interest so I just want to indicate certain things I marvel at. Note how Esther/Garland beckons the musician to her at the beginning. Throughout this sequence she will be in constant communication withe the various musicians (see figures A,E,L and Q as only representative examples), she will also be conveying the meaning of the song, losing herself in it, running to the camera (fig J), and fearlessly turning her back to it (fig K), whilst also conveying Esther, an insecure star-in-waiting, one of the boys in the band, who does this as if it’s nothing, yet giggling and winking at them at the end for the joy of a job well done (see figure Q). Garland must perform all of this whilst being conscious of always hitting her mark, always being in the light, always co-ordinating each of her movements with the band, which has been clearly choreographed compositionally. It’s a tour de force.

And it’s a tour de force of direction. Cukor performs a high-wire act of direction because Garland is always at the centre, the camera will tilt upward or move slightly to ensure she’s always in the frame; yet on the other hand every stop in the camera’s movement has been designed to create an abstract geometric shape amongst the musicians, usually framing Garland, usually at the top (figs D, E) or bottom (figure M, O) of a triangular shape.

Every area of the cinemascope frame is deployed expressively. Each shape made seems beautiful, each is meaningful. In the world of the film, we are introduced, through Norman Maine’s to his love, who will not save him from all the darkness he’s encased in. Note how they’re both wearing variants of the same outfit, black suit with a white collar. They’re meant for each other. But she, encased in light and amidst coral pink will not save him from himself. We’re also introduced to a great talent which the film tells us is Esther Blodgett but who will become Vicky Lester but who we know to be Judy Garland. The Judy Garland who can do the extraordinary things we’ve just witnessed thanks to George Cukor’s extraordinary use of colour and composition in one of the greatest of long takes.

Fig a

Fig B

Fig C

Fig D

FIG E

Fig G

Good riddance

Fig H

FIG I

FIG J

FIG K

FIG L

FIG M

FIG N

FIG O

FIG P

FIG Q

wink and giggle.

José Arroyo

The Man That Got Away ‘The Man That Got Away’ number in the 1954 version of A Star is Born directed by George Cukor is widely acknowledged as one of the very greatest in the history of the musical genre.

0 notes