#then 1000% more when I saw the guest historian

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I'm listening to a podcast episode about Eleanor of Aquitaine, who was married to a couple of kings and mother to more kings, and the podcast host just about slew me by saying:

"How many kings are in and out of this woman's vagina is quite impressive."

#betwixt the sheets#Kate Lister#I mean I was 1000% on board when I saw the episode topic#then 1000% more when I saw the guest historian#(Eleanor Janega my beloved)#this is just icing on the cake and honestly par for the course with these two

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

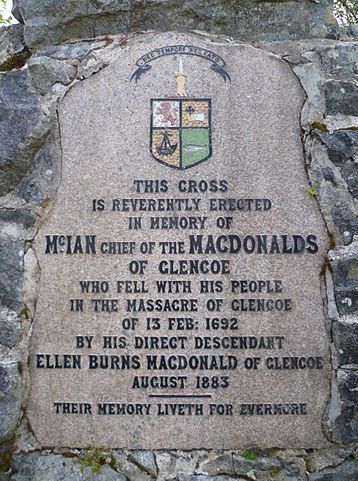

On February 13th 1692, a Royalist force, under the command of Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon, carried out the Massacre of Glencoe.

A rather long post but I feel that some people are under the illusion that the events that occurred at Glencoe 326 years ago was a Clan thing between the MacDonalds and the Campbells.

Early that morning in the aftermath of what has been termed the Glorious Revolution and the Jacobite uprising of 1689 led by John Graham of Claverhouse, a massacre took place in Glencoe, in the Highlands of Scotland. This incident is referred to as the massacre of Glencoe, or in Scottish Gaelic Mort Ghlinne Comhann or murder of Glencoe.

The massacre began simultaneously in three settlements along the glen—Invercoe, Inverrigan, and Achnacon—although the killing took place all over the glen as fleeing MacDonalds were pursued. Thirty-eight MacDonalds from the Clan MacDonald of Glencoe were killed by the guests who had accepted their hospitality, on the grounds that the MacDonalds had not been prompt in pledging allegiance to the new monarchs, William and Mary. Many more died due to the harsh weather conditions as they fled the carnage.

So why did this atrocity happen? Well the Highland Chiefs were given an ultimatum to swear an allegiance to William and Mary or suffer the consequences, a deadline was set of January 1st 1692, MacIain of Glencoe, the-old Chief of the MacDonald Clan left it late, he also mistakenly set out for Fort William, where the governor, Lieutenant Colonel John Hill told him he was not authorized to receive the Oath, Hill sent MacIain to Inverary with a letter for the local magistrate, Sir Colin Campbell. The letter confirmed MacIain's arrival before the deadline and asked Sir Colin to administer the Oath. He did so on 6 January and MacIain returned home.

With that the oath signatures, the letter, and other business was sent by dispatch to Edinburgh Privy Council. Colonel John Hill sent a letter to MacIain in Glencoe, as was the protocol, stating that clan MacDonald was now under the protection of the garrison at Fort William.

When the package of oaths was presented before the Privy Council in Edinburgh, among them was another letter from the sheriff asking whether Chief MacIain’s signature should be accepted or not. The clerks of the Privy Council, among whom were powerful Campbell lawyers, would first have put all the information into a presentable order to come before the Privy Council. Historians suspect that some corruption of the information may have taken place here, but this can’t be proved. Whatever was presented to the Privy Council caused them to declare that MacIain’s signature was unacceptable, an illegal late submission, and to order it be struck from the record.

Just five days after MacIain had signed the oath, Dallrymple received word that his name had been removed from the list due to a ‘technical fault’. Dallrymple, the joint Secretary of State for Scotland was gleeful, he had a deep hatred of the Highland clans and so no place for them in scheme of things in a modern Scotland.

He wrote: ‘just now my Lord Argyll tells me that Glencoe hath not taken the oath, at which I rejoice.’ Other clans had not taken the oath either, bad weather or refusal had prevented them. But Dallrymple singled out the MacDonald Clan. He went on to say ‘It’s an act of great charity to be exact in routing out that damnable sept, the worst in all the highlands.’ Quite why he hated the MacDonalds more than any other clan is not known. They may have been naturally rebellious and given to banditry, but they were certainly not the only clan with those qualities. Other rebellious clans, were more powerful, with better connections. The MacDonalds though were insignificant enough to be made an example of without reprisals from other clans. Fate and circumstance had dealt an already unfortunate clan a nasty card.

Dallrymple urged the king to act, making particular reference to the MacDonald Clan. The commander-in-chief in London received the king’s final instructions which he sent back to Dallrymple in Edinburgh. Colonel Hill tried to postpone military action against the highlanders. He wanted to give them a chance to make their case. But he was overruled. Two of his officers, Major Duncanson and Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton planned the attack, acting directly on specific orders from Dallrymple. Dallrymple knew that MacIain and the MacDonalds were under the illusion of safety, and he used that knowledge to plan a covert action. It was also an illegal action, a form of treason known as ‘slaughter under trust’.

Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon was given the command of two companies of about 120 men in total. On 1st February 1692, ten days before the massacre, they were ordered to march into Glencoe and await further instructions. It is unlikely that Glenlyon knew at this point what he would be ordered to do next.

At 60 years old Robert Campbell of Glenlyon had never made it higher than captain. He was not a successful man. He was a heavy drinker and an inveterate gambler, a black sheep of the Campbell family. Historians have speculated that this man was chosen especially for the job because of certain weaknesses in his character, and because no one would care if he took the fall. An even more cynical reason presents itself: Glenlyon was related to MacIain. The betrayal would be all the more acute.

When the MacDonalds of Glencoe saw the redcoats marching over their valley it must have been quite a shock, however they were under the protection of Fort William garrison and had no reason to fear these soldiers. Instead at the company’s request to be billeted, they welcomed them into their homes and gave them food and drink. Glenlyon told the Chief they were collecting taxes from each clan, by order of Colonel Hill. He could even produce papers to that effect. This satisfied the MacDonalds. The captain, Glenlyon, was billeted in the Clan Chief’s own house. Glenlyon’s neice was married to MacIain’s youngest son, and Glenlyon also visited daily with his niece and her new family. The rest of the company were billeted in homes up and down the valley about 3 or 4 to a house. Unknown to Clan MacDonald fatal danger now lay within the heart of each home.

For ten days the soldiers stayed, ate and drank, played cards, gambled and sang songs. Some even shared female beds. They belonged to the same highland culture; in that culture it is understood if you invite a stranger into your home and break bread with them, they are no longer a stranger but a trusted friend. Mutual protection was assumed. This code was sacred to Highlanders. Ten days and nights, then, of friendship and community the hosts shared with these soldiers, and the soldiers shared with their hosts. It makes what happened next all the more appalling.

On the night before the massacre Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon, who was dining with his host, Alistair MacIain and his family, received a dispatch from Major Duncanson, who was stationed outside the glen. The letter is now an infamous one. It said: by order of the king, at five o’clock the next morning every member of Clan MacDonald under seventy must be ‘put to the sword’, and on no account must the ‘old foxe and his sones’ escape the slaughter. If Glenlyon did not carry out this command he would be ‘dealt with as one not true to King nor government’ in other words he would be deemed guilty of treason. It is hard to imagine with what misgiving Glenlyon relayed this message secretly to the other soldiers billeted along the valley that night. But that was the command and it had to be carried out.

Major Duncanson told Captain Campbell he would join him, but he ordered him to start the action 2 hours before he was due to arrive on the scene. In the end bad weather forced him to arrive 6 hours later. A Campbell was to be the main instigator. Very few of the soldiers bore the Campbell name. Most were lowlanders. But the name Campbell had to stick to this crime one way or another.

Next morning on the 13th February 1692, in the dark of early morning, the massacre began. MacIain was slaughtered in his bed, but MacIain’s two eldest sons both managed to escape into the mountains. In total around 38 people were killed. All along the valley crofts were set on fire. It is not known exactly how many of the women and children who escaped later died of exposure. Estimates range between 40 and 300.

Some historians suggest the troops must have known before the orders came that they were there to commit an atrocity. Some historians suggest that although the soldiers carried out their orders, they deliberately did it badly, or simply couldn’t do it. According to one account some soldiers broke their swords rather than murder their kin. Of the 1000 or so people who lived in Glencoe, 38 ambushed is by no means a large number for a company of 120 armed men.

Before nightfall on the 13th February, some of the survivors ventured down from the mountains to bury their dead relatives. The clan chief and his close family were given their due burial in the MacDonald burial ground, the island of Eileen Munde on Loch Leven. Others were buried in and around the glen.

Dallrymple, when he heard the news that the massacre had not been complete, that two of the ‘old fox’s’ sons still lived, was furious. He wanted to prove to the king that he was the man to control the Highlanders. He ordered that the survivors be hunted down, sent to the plantations or killed. He wrote letters urging this, but it was never carried out. His vengeful, unrepentant attitude was not shared by others, who were horrified at what had happened.

After the event Glenlyon was seen in Edinburgh getting drunk and lamenting what he had done. The soldiers too began to speak of it, of the terrible thing they had been ordered to do. Journalists picked up on the information with interest. Somehow Glenlyon lost the written order to attack. It was picked up and sent to Paris. There it was published in the Paris Gazette and news spread across a shocked Europe of the atrocity. It was not going to just go away.

King William was fighting battles in France, and, to his shame, ignored what was happening in Scotland. Dallrymple was never disciplined for the disreputable order. Colonel Hill too seemed unconcerned, despite recognising MacIain’s desire to make the oath. He wrote to the Lord Chancellor of Scotland telling him in a military report that he had ‘ruined Glencoe’, among other business. If he had misgivings he didn’t share them.

At this point Charles Leslie, Jacobite barrister, tabloid pamphleteer and political propagandist decided to seek the whole truth. He was thorough and precise, collecting documentary evidence, talking to the soldiers and recording eye-witness accounts. Parliament tried to dismiss his findings as a Jacobite conspiracy theory. Queen Mary, however, started asking questions. By 1693, with Charles Leslie stirring up the public and Queen Mary putting pressure on the government, King William was forced to hold an official enquiry. It was a cover-up, exonerating the King, and no one was satisfied with it. Questions continued to be raised in Parliament.

In 1695, the year following Queen Mary’s death, there was a second enquiry. This time the king was not allowed to look at the report before publication. The second enquiry went further. It concluded that an act of treason had been perpetrated on the people of Glencoe by their own government. But who would take the actual blame for this crime? In the first instance it decided a ‘mistake’ had been made not accepting MacIain’s oath.

The King was once again spared from blame. Dallrymple was deemed to have ‘wrongly interpreted’ the king’s wishes. He was dismissed from his post as secretary of State for Scotland. Later the 19th Century politican and historian, Thomas Macaulay, accused King William of a ‘great breach of duty’ in not disciplining Dallymple further. Not long after, through the revolving door of politics, Dallrymple was back in office. After William’s death in 1702, he played a key role in forming the single state of Great Britain.

The axe fell heaviest on Robert Campbell of Glenlyon and the other officers involved that day. They were found guilty of ‘slaughter under trust’, despite the fact they were following the orders of their superiors. Parliament recommended they stand trial. In the end no one did. Robert Campbell of Glenlyon died of alcoholism. He never recovered from the burden of following those orders. It was recommended to the king that Major Duncanson and Lieutenant-Colonel Hamilton should also be made to answer questions. The king declined to act.

As for the MacDonalds, they returned to their glen, they re-built their houses and re-settled their families. John MacIain, eldest son of Alistair, became the 13th Clan Chief, building his home on the site of his father’s house. Three hundred years later opinion is still sharply divided on whether Clan Campbell should be held accountable for the murders. The truth is too complicated to unravel. I myself can be a forgiving person and hold Dalrymple most accountable, it's a shame he was never brought to task for the murders. The Campbell's around the Highlands in my opinion were not complicit in the murders, the high heid yins in Edinburgh though were probably up to there ears in it, although to what extent they knew of the planned attack is debatable.

I was going to post a pic of Dalrymple but decided against it, instead we should remember the people of Glencoe who were wronged in a horrible way that day.

61 notes

·

View notes