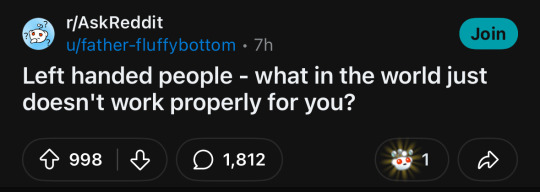

#the upright pyrex ones are better

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

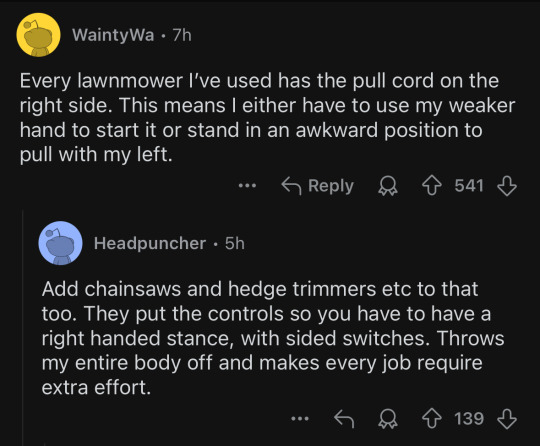

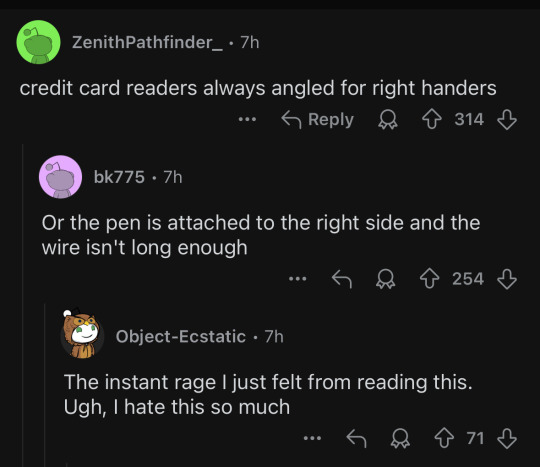

Measuring cups! The flat ones with long handles, if they have a spout, a lefty has to choose between the lack of control of pouring out of the edge with no spout, and the lack of control of pouring with one's off hand.

and my personal favorite:

i love getting validation as a lefty but also learning about new fun ways it continues to suck

#the upright pyrex ones are better#but our set at least has imperial volume marked on the side visible if held in the right hand#and metric on the left#and since i am not often making a recipe in milliliters#i generally have to set a measuring cup down and rotate it 180 degrees#to check that i filled it the right amount

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s a big ol’ chunk from a fic I’ve been working on for a while. Clint and Bucky get stuck on the old Barton Farm while the superhero world kind of has a crisis around them. Also there’s a baby.

Unfounded rumors don’t spread well in towns like Waverly.

There’s not enough people to warp a story like there are on the afternoon soaps. If you swap news with old Mrs. Kitchens while you tend to your garden, or if you hear a tale from Joe Mercer while you’re down at the bar, you’re likely to get a whole list of everyone that’s told them about it, too. Any tale too fishy usually fizzles out before it can make it down the first street.

That doesn’t mean the folks in Waverly don’t gossip. By the time Rachel Murphy finally gets the chance to bake a green bean casserole for her alleged new neighbors, she’s already been told by at least fifty people that one of the Barton boys has moved back in town.

It’s not happy gossip, like when Joyce Ellars gave birth to twins when she and Owen had been counting on just one. The Barton boys never got too much happy gossip, even when they were still in Waverly. Instead, Janice MacMillan tells Rachel the news just like Russell did, voice low and brows pinched with worry.

“You’d better keep Jack on your side of the fence,” Janice says as she helps Rachel wash off the green beans. “The Barton boys always were bad news.”

The Barton farmhouse doesn’t look much better now than it did for the last seventeen years, but even as Rachel picks her way around the collapsed fence posts in the front yard, she can tell someone’s been fixing the place up. The boards have already been pried off the second-floor windows, and the shutters have been thrown open to air out the place. Yesterday she saw the windows backlit late into the night as someone put in new bulbs, and as Rachel knocks against the familiar front door, she can tell someone’s already been scraping off the peeling brown paint in preparation for a new coat.

A window is open around back, near enough that Rachel can hear voices inside without knowing what they’re saying. The sound of footsteps tells her that her knock was heard, and she tightens her grip on her tupperware, wishing any of the town’s biggest busybodies had been able to tell her which Barton had come back home.

The door doesn’t swing open, though, and after a moment’s pause, the footsteps retreat. Rachel hovers on the front step, wondering if she should try the back door instead.

“Who was it?” A voice calls out, close enough to the open window that Rachel can hear it clear as day. There’s a muffled reply, and then footsteps again. “Bucky,” the voice scolds as it draws closer to the door. “You can’t just leave someone outside if they brought a casserole.” That gets an answer that Rachel still can’t hear, and then the door is thrown open.

“No, that’s not a me thing,” the man calls over his shoulder. “That’s a midwest thing, you goddamn city slicker.”

“Clint Barton,” Rachel says, gripping her casserole dish as she meets familiar cornflower-blue eyes. Recognition dawns on Clint’s face faster than she expects it to, and she sees his jaw stiffen.

“Rachel Wilkes,” Clint says, something guarded in his voice, almost suspicious. His gaze sweeps over her shoulder, like he’s scanning for the rest of the welcome wagon.

“It’s just me,” she says as Clint’s eyes settle back on her, taking in the changes of seventeen years. “Actually, it’s Rachel Murphy now.” Clint’s eyebrows raise, but he doesn’t look surprised. Politely disinterested, maybe.

“You stuck with Roy, huh?”

“I brought you a casserole.”

She’s deflecting, holding the pyrex dish out like a shield between old memories with sad blue eyes. Clint steps out of her way automatically, almost before his face has time to react. Something in the back of Rachel’s head wants to smile. You can take the boy out of Iowa, but a green bean casserole is still a peace offering nobody can turn down.

“Thanks,” Clint says, almost on autopilot. He starts to lead her toward the kitchen before he’s hit by some other thought, rocking back mid-step. “Aww, the kitchen’s full of junk right now. Some shelves broke when I was getting the fridge set up last night. It’s kinda treacherous.” They both look down at Rachel’s flats, clearly too dainty to navigate a floor full of splintered shelving. She pushes the tupperware into Clint’s hands instead.

“I’ll wait here.”

Clint nods before shooting a look into the living room, and Rachel remembers the second voice. She turns to the figure she’s just noticed as Clint slips into the back of the house.

There’s a man sitting on the dusty couch, legs pulled up off the floor and arm cradling a bundle. He’s got long hair, longer than Rachel’s ever seen on a guy, and there’s something dark and wary in his eyes. He seems to have tuned her out, though. He’s got something wedged on his shoulder, and the bundle in his arm is starting to make a high-pitched noise of complaint. It takes Rachel a moment to realize he’s trying to feed a baby one-handed.

There’s a cascading crash from the kitchen, which seems to tip the whining bundle over the edge, and the living room is suddenly filled with loud wails. The man with the long hair looks up, glaring through walls in the direction of Clint’s shouted “Sorry!” He tries to shift again, shushing the baby, or maybe Clint. Rachel chews her lip, hovering at the threshold of the living room.

“They won’t latch on at that angle,” she finally blurts out. The man looks up in surprise, and the bottle drops into his lap. Rachel steps forward cautiously, reaching out for the baby. The man frowns at her, his face creasing with worry.

“You a nurse?”

“A mother,” she says, and she thinks his face softens, if only a little. The man sighs, making room for Rachel on the couch. He lays the baby into her arms as she sits, and it only hits her then that he wasn’t feeding one-handed for the challenge. His left arm stops just a little past the shoulder.

Rachel shifts the baby around, ignoring the wails that have faded into wet sniffles. She brushes the tears from round cheeks before taking the bottle that the man hands her, settling the baby into the crook of her arm.

“Is it a boy or a girl?” she asks, pressing the bottle softly against the baby’s face. Cornflower-blue eyes look up at her, tear-flushed cheeks fading a bit as the baby latches onto the bottle almost right away.

“Girl,” the man says, leaning carefully over Rachel’s arm to watch. “How’d you get her to do that?”

“You had her too far upright,” Rachel answers, not looking away from the big blue eyes. “She’ll get fussy if you don’t lay her at the right angle.” The man makes a frustrated sound, and Rachel looks over to see him frowning at his left side, clearly trying to plan the logistics of future feedings. “I have some old nursing pillows in my basement,” she says. “I can bring them over, if you want. I think they would help.”

“You don’t need them?”

“My boys are nearly grown,” she tells him. “We live just down the road, so it’s no trouble. I can get my oldest to bring them by.”

The man looks down at the baby in Rachel’s arms, pressing his lips together as he thinks over the offer. He reaches for the baby’s hand with one finger, the corner of his mouth twitching up as she curls a tiny fist around it.

“That would help,” he says finally, his voice soft. Another moment passes before he looks back up at Rachel. “I’m Bucky.” His eyes are a stormy grey, and somehow familiar.

“Rachel,” she offers. Bucky really does smile, then.

“That was my sister’s name. Thought we could call her Rachel until Clint decides to keep her after all.” Bucky nods at the happily feeding baby, and Rachel is so surprised at the statement that Bucky talking about his sister in the past tense slips right past her.

“Clint’s not keeping his-?” She can’t get the question all the way out before Clint walks back into the living room, the palm of his right hand wrapped in bandages. Bucky rolls his eyes as Clint nurses his casserole-induced wound.

“She’s not my kid,” he says, fixing Rachel with the same blue eyes that the baby in her arms has.

“Oh, I’m sorry. I assumed-”

“She’s Barney’s.”

“Oh.”

Clint rubs his palm against the back of his neck, a habit he’s had since junior high, and it hits Rachel then, how much time has passed. Clint’s not the gangly teenager he was last time she saw him, but there’s still that roundness to his shoulders, the hunched stance of someone who spent their formative years trying to hide from the world.

“How’s Barney?” Rachel says, and it’s not one of the hundred or so questions she’d like to ask Clint, but it’s a start. Clint looks at the floor, trying for a nonchalant shrug even as he wrings his hands.

“Dunno. Dead, maybe. He was in jail the last time I saw him, but that was three years ago, so.” Clint shrugs again before planting his hands on his hips. “Thanks for the casserole.” It’s a clear dismissal, but Rachel’s still holding the baby and the bottle, and Bucky doesn’t move as if he wants her to go.

“Clint,” Bucky says, his voice gentle, and Clint drags his eyes up from the floor like he can’t stop himself. “Rachel has some old nursing pillows she’ll lend us.”

“We don’t need those,” Clint says, but it’s directed at Bucky. “We picked up all the baby stuff we need on drive over.”

“We could use the help,” Bucky says, and there’s something beneath the surface of his words, an undercurrent of meaning that Rachel isn’t sure she understands.

“We’re fine on our own.”

“There’s a splintered pile of wood in the kitchen.”

Clint sighs, looking between the two of them.

“Fine,” he says, shuffling closer and dropping into an armchair that’s almost as dusty as the couch. “We could use the pillows. I’ll pick them up tomorrow. I have to go into town anyways.”

“No, I’ll call my boys. Jack can bring them over.”

“Jack?” There’s a quirk to Clint’s brow that says he’s asking out of more than just politeness now.

“My oldest,” Rachel explains, setting down the now-empty bottle and moving to put the baby against her shoulder. There aren’t any burping cloths in sight, and Clint and Bucky haven’t moved to find her one, so she makes the executive decision that a little spit-up on her shoulder wouldn’t be the end of the world. “I’ve got two boys. Jack’s just turned seventeen, and Tommy is fifteen.”

“What’s Roy up to, these days?”

“He died in Afghanistan. Six years ago, next month.”

Clint blinks, his face caught between surprised and sympathetic. Rachel pats the baby against her shoulder.

“I’m sorry,” Clint offers after a moment, but Rachel shakes her head.

“It was a while ago.” She wants to say more. Something like It wasn’t all bad, or You were right about him, Clint. She doesn’t, though, and the room falls silent. Rachel feels Bucky lean in closer to her, and she almost thinks he’s about to hug her before she feels the baby being lifted off her shoulder.

“Well,” he says, propping her up against his own shoulder and craning his neck to watch her eyes droop. “I guess I can’t call her Rachel if you’ll be sticking around. Too confusing. What about Hannah?” The baby nestles against him, and Bucky hums as if she’s just given her approval. Clint snorts from his armchair.

“Stop trying to name my niece after your sisters,” he says, and Bucky pouts.

“Tzipporah?”

“Wow, someone got the short end of the stick in your family,” Clint says. Bucky glares at him.

“Just because your dumb ass can’t spell it doesn’t make it a bad name,” he grumbles. “I bet your family names aren’t any better, Clinton Francis.”

“You wound me. You really do,” Clint says. “Why does she need to be named after a relative, anyways? You’ll just get attached.”

“I’ll get attached anyways,” Bucky says as the baby snuffles into his shoulder. “I’ll name her after a friend, then. How about Dolores?”

“Hard pass.”

“Geraldine?” Bucky says, and Clint gives him a warning look.

“You’re doing this on purpose.”

“Ethel,” Bucky says with finality, and Clint throws up his hands, jumping up from the armchair.

“Don’t pull the old-fashioned innocence routine on me, Barnes. Those are terrible names, and you know it.”

“Irma?” Bucky offers, and Clint crosses his arms.

“You know what? Fine. Name her after your family. I don’t care. But when we get back to New York, I’m telling everyone she’s your kid and you’re gonna be stuck with her.”

Bucky looks satisfied with that, running his fingers through the baby’s soft brown hair.

“I’m calling her Naomi,” he says, and he beams when he realizes Clint hasn’t rejected it yet.

“Like the model?” He rubs a palm over the stubble on his jaw, considering it.

“Like my great-aunt. And Ruth’s mother-in-law.”

“I keep telling you, I don’t know any of your old girlfriends.”

“It’s from the bible, you heathen.” Bucky rolls his eyes, but presses a satisfied kiss to Naomi’s head.

“Barney’s gonna be so pissed if he comes back and finds out we raised his daughter Jewish.” But Clint looks fond, and Bucky beams at him.

“We’ll give her a bat mitzvah and everything. I hear they do them all fancy these days.”

Clint looks like he’s already developing an ulcer over the party expenses.

37 notes

·

View notes