#the nuclear family structure is a heteronormative and patriarchal concept

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Do you have any thoughts on the abolition of the family?

why did this ask get formatted into a column?

edit: okay so now its normal

#the nuclear family structure is a heteronormative and patriarchal concept#designed to align with class interests that enforce typical western gender roles

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Module 2 - Week 8 Family

This week's required readings were "The origin of the Family" by Kathleen Gough and "Kiss the Family Goodbye" by Adolph Reed Jr.

I'll be honest, at first glance, I disagreed with the main ideas in this week's readings because I grew up in a heteronormative nuclear family that feels like how Tyler Childers's song sounds. However, after some reflection, I realize that there is more to the argument than simply being against the "family."

Both Gough and Reed demonstrate that the concept of family is not as fixed as I believed it to be. Modern-day North Americans traditionally consisted of and idolized the nuclear family, which consists of a female-identifying partner and a male-identifying partner that are legally bound to each other and are committed to raising children. However, due to changes in our social, cultural, and economic structures, we are growing to accept an even more diverse version of "family." This includes but is not limited to families with single parents, same-sex parents and chosen families.

These new family structures are challenging the traditional patriarchal values that are ingrained into us. Reframing how we define family offers new ways to include those who feel disconnected from the nuclear family narrative. The work of Gough and Reed shows that family can be based on shared values and common interests rather than biological and legal definitions. Further, representing these alternative families in popular media like television shows helps normalize their structure in society.

Gough's study of family and kinship across cultures and time periods suggests that the idea of "family" was highly influenced by cultural factors like the division of labour and social hierarchies (767). She then compares how the family was constructed and utilized in everyday life among Eskmio societies, the society of the congo Pigmies, to show that the subordination of women plays a key role in the creation and maintenance of the nuclear family (765-6). Gough also describes the nuclear family as an institution (767). I thought that this take on the family was super interesting and helped me comprehend the lure of the nuclear family and why the conservative party is enchanted by it.

Similarly, Reed uses critical analysis to argue that family is a social construct shaped by capitalism that promotes conservative values and supports traditional gender roles (115-16). I have seen memes on Reddit and Facebook that both agree and disagree with Reed's statement. These relatable memes show the pressure to produce a nuclear family in North America and playfully oppose or support conservative ideology. For example:

After some reflection, I have realized that the discourse present in Gough and Reed's work centred on family is part of a larger conversation about identity. The family socializes individuals as well as shapes a sense of identity. I agree with Gough and Reed that the origin of the nuclear family is problematic in terms of its subordination of women and therefore has social and personal effects. These effects are reflected in the media we consume. Most notably, I think of the Gossip Girl books I read in middle school that influenced me to believe that family (and money) were the most important parts of one's identity.

In reading Gough and Reed's work, I learned that there is a huge difference between advocating for the cancellation of the nuclear family entirely and the urge to redefine the concept of family in a way that accentuates each group's unique authenticity. Gough and Reed make it clear that the solution to combat the family rhetoric of conservative politics is to achieve the latter. I think that using popular forms of media, such as TV shows, would achieve a redefinition resulting in more acceptance for families that divert from the norm.

In terms of how the family is presented in media like TV shows it is overwhelmingly similar to the conservative ideology. However, a popular positive diversified example that comes to mind is the hit TV sitcom, Modern Family. While the show is far from perfect, it is a step in the right direction in depicting a reformed version of family. Newer examples include Eleven and Hopper's family in Stranger Things and Shaline Woodly's character's family in Big Little Lies. As were have discussed throughout the course, representation matters and shapes how we think about the world. I am excited to see how future sitcoms will reinforce or fight patriarchal stereotypes.

I have included some iconic moments of the gay couple Cam and Mitch from Modern Family, just because I love this show!

youtube

0 notes

Text

Why Black Lives Matter? An explanation for those who do not understand.

Photographer: Clay Banks | Source: Unsplash

What does Black Lives Matter mean?

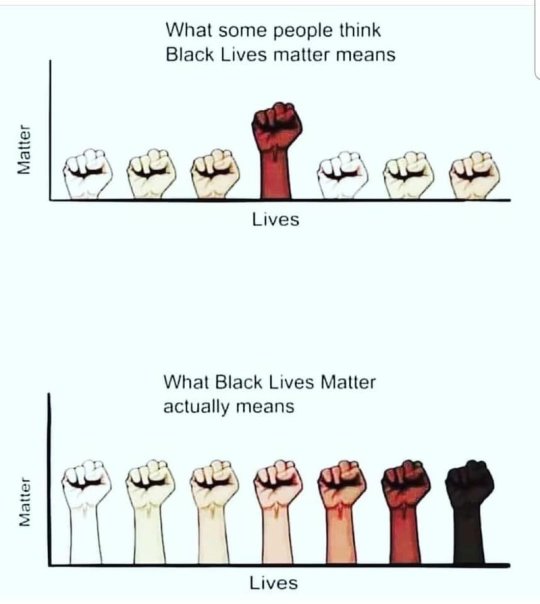

Black Lives Matter simply means that the lives of Black people are important. It does not mean that Black people are more important than others. It serves as a reminder that they are important. If you feel that Black Lives Matter is an unfair statement remove the invisible “only” from the beginning of the statement and add an invisible “also” to the end (Only Black Lives Matter versus Black Lives Matter Also). Here is a chart to help explain this further.

The movement vs the organization

There is a huge misconception on multiple fronts regarding Black Lives Matter (BLM), so I am going to try and clear up some of the confusion. On one hand many believe that Black Lives Matter is an organization that is behind the movement Black Lives Matter and many do not want to participate in the movement because they do not agree with the tenants of the organization. While there is an organization called Black Lives Matter and it does support the Black Lives Matter movement, it is not entirely responsible for the Black Lives Matter civil rights movement.

While the organization does support the movement that shares its name, the org does not own the phrase Black Lives Matter. There are many organizations and individuals involved in and supporting the movement who have nothing to do with the Black Lives Matter organization. A person can attend a march, protest, or even say Black Lives Matter without agreeing with or supporting the organization Black Lives Matter. For those just learning about the Black Lives Matter organization and wondering what they are about and what may be disagreeable or controversial about it, I will give more information and try to remain unbiased.

youtube

Here is a history of the BLM Movement through the lens of a British news channel. I chose this because I felt that having a foreign perspective would help remove some bias.

Black Lives Matter organization

The Black Lives Matter organization was born from the #blacklivesmatter movement. In fact, one of its founders came up with the hashtag. Here is what the organization is according to its website BlackLivesMatter.com/About

Black Lives Matter Foundation, Inc is a global organization in the US, UK, and Canada, whose mission is to eradicate white supremacy and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes. By combating and countering acts of violence, creating space for Black imagination and innovation, and centering Black joy, we are winning immediate improvements in our lives.

What the Black Lives Matter organization believes

Here are the tenants of the Black Lives Matter foundation also found on its website at blacklivesmatter.com/what-we-believe/

We acknowledge, respect, and celebrate differences and commonalities.

We work vigorously for freedom and justice for Black people and, by extension, all people.

We intentionally build and nurture a beloved community that is bonded together through a beautiful struggle that is restorative, not depleting.

We are unapologetically Black in our positioning. In affirming that Black Lives Matter, we need not qualify our position. To love and desire freedom and justice for ourselves is a prerequisite for wanting the same for others.

We see ourselves as part of the global Black family, and we are aware of the different ways we are impacted or privileged as Black people who exist in different parts of the world.

We are guided by the fact that all Black lives matter, regardless of actual or perceived sexual identity, gender identity, gender expression, economic status, ability, disability, religious beliefs or disbeliefs, immigration status, or location.

We make space for transgender brothers and sisters to participate and lead.

We are self-reflexive and do the work required to dismantle cisgender privilege and uplift Black trans folk, especially Black trans women who continue to be disproportionately impacted by trans-antagonistic violence.

We build a space that affirms Black women and is free from sexism, misogyny, and environments in which men are centered.

We practice empathy. We engage comrades with the intent to learn about and connect with their contexts.

We make our spaces family-friendly and enable parents to fully participate with their children. We dismantle the patriarchal practice that requires mothers to work “double shifts” so that they can mother in private even as they participate in public justice work.

We disrupt the Western-prescribed nuclear family structure requirement by supporting each other as extended families and “villages” that collectively care for one another, especially our children, to the degree that mothers, parents, and children are comfortable.

We foster a queer‐affirming network. When we gather, we do so with the intention of freeing ourselves from the tight grip of heteronormative thinking, or rather, the belief that all in the world are heterosexual (unless s/he or they disclose otherwise).

We cultivate an intergenerational and communal network free from ageism. We believe that all people, regardless of age, show up with the capacity to lead and learn.

We embody and practice justice, liberation, and peace in our engagements with one another.

Is Black Lives Matter a Marxist organization

One of the biggest problems I’ve heard people say that they have with the Black Lives Matter organization and movement is that it was founded by a Marxist. While there have been interviews where the founders have mentioned that they are trained Marxists I have not read any particularly Marxist ideology in any of the literature about the Black Lives Matter organization and I do not see any Marxist ideology reflected in the movement. I do think that the average person does not understand what Marxism is so I will provide a definition. Marxism is a doctrine developed by Karl Marx that included economic and political ideology that is considered the foundation for socialism. Where Marxism gets its bad wrap is its variation, Soviet Marxism adapted by Vladamir Lenin and Joseph Stalin that became the foundation for communism. While I do not know which type of Marxism the founders of the organization were trained in; I will assume it was the original version that gave way to socialism. I came to this conclusion because many of the policy changes both the organization and movement are advocating for, involve reallocating government funds to programs and resources for communities. I am including two short videos one explaining the original form of Marxism and the other explaining Soviet Marxism.

youtube

An introduction to Classical Marxism

youtube

An explanation of Leninism or Soviet Marxism

Why is it not alright to say All Lives Matter?

While answering this question I am making one assumption about the person asking the question and that is that this person truly believes that everyone’s life has meaning and is important so they believe that Black Lives Matter is an extension of All Lives Matter and therefore saying All Lives Matter includes Black people. While this sentiment seems obvious it is not that simple. All Lives Matter has become a phrase that is used in response to Black Lives Matter in order to discredit issues brought up by the Black Lives Matter movement. The analogy I find helpful is saying All Lives Matter in response to Black Lives Matter is like saying all diseases are harmful when someone is talking about the dangers of breast cancer. Here are a few other analogies others have found helpful.

youtube

youtube

youtube

Takin from Ben Brainard on TikTok

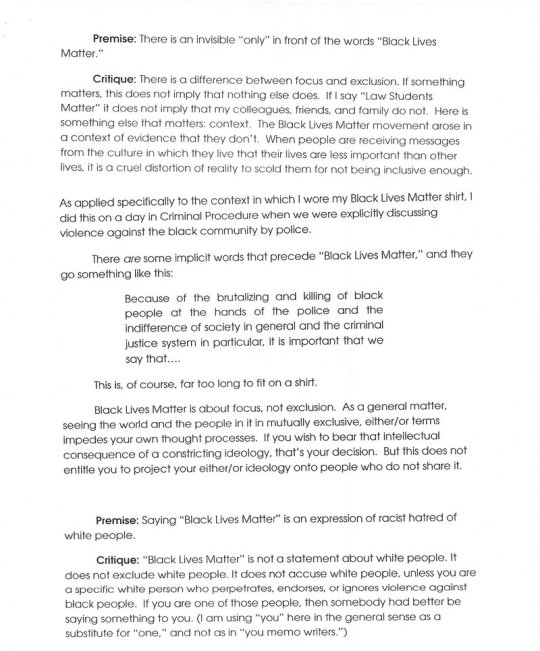

Taken from a Law Professors Response to a BLM Shirt Complaint

What about black on black crime (aka crime)?

After hearing about the Black Lives Matter movement many people ask about black on black crime and what the movement is doing to solve this issue OR why it hasn’t done anything about this issue. First, as someone who has studied the migration and settlement of people and people groups as well as community and economic development I would like to say, backed up by all of my formal and elective education, that black on black crime is not real. It is just crime. Black on black crime is a concept that was created to support the stereotype that black people are inherently more violent than others.

In America, crime is committed by people in close proximity. This means that the majority of crimes are committed by people in the same community as their victims and unfortunately (at least in my opinion) many communities are still segregated. This means that most white people live in communities that are predominantly white, most black people live in communities that are predominantly black, most Hispanic people live in communities that are predominately Hispanic, etc. This means that white people are more likely to commit a crime against another white person, black people are more likely to commit a crime against another black person, and so on. Many people know the statistic that one is more likely to be sexually assaulted by someone they know than by a stranger, well this statistic holds true across all types of crime.

With that being said, I would like to address the portion of the argument that asks why BLM is not addressing crime in the black community. The answer is because this is not the mission of the movement or the organization. There are specific organizations such as the National Urban League that actively address issues that cause crime in urban areas. Here are a couple of videos that provide additional points of view.

youtube

youtube

Takin from Ben Brainard on TikTok

Conclusion

I just wanted to add a bit more of my opinion. While I attempted to remain unbiased I’m sure some of my own implicit biases made their way into this article. I would like to add some context so that anyone who reads this may see where I’m coming from and understand those biases. I am a 34-year-old black woman who graduated from the United States Military Academy (GO ARMY!) and served for 5 years on active duty to include one tour to Iraq. I love my country and desire for it to be everything and more than I could ever imagine.

While I have not experienced first hand some of the experiences of those who are active in the BLM movement, I have experienced overt racism on many occasions in my life and I do believe that less obvious forms of racism, such as systemic racism and unconscious negative biases toward people of color, exist in our country. I recognize that I grew up privileged in that my parents made the decision to give me a private school education, even though it made things more difficult for them financially. I had the privilege of growing up with a mother who went to college and was very active in helping me take the necessary steps to apply to and get accepted into one of the best institutions of higher learning in the country. I recognize that as a heterosexual, cisgender, able-bodied person I have the privilege of fitting into society’s idea of what a “normal” woman’s life looks like. In acknowledging the ways that I am privileged I am in no way saying that my life is easy. I have had many struggles and hardships but none of them were because of my gender identity, sexual orientation, physical abilities, or education.

That being said, I will do everything in my power to make this country one where every person, regardless of their identity, is treated with the dignity and respect that every human life deserves.

if(window.strchfSettings === undefined) window.strchfSettings = {}; window.strchfSettings.stats = {url: "https://kesha-janaan.storychief.io/en/why-black-lives-matter?id=2038645149&type=27",title: "Why Black Lives Matter?",id: "2f87ac84-0907-4b5a-922a-1efc62960e90"}; (function(d, s, id) { var js, sjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) {window.strchf.update(); return;} js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "https://d37oebn0w9ir6a.cloudfront.net/scripts/v0/strchf.js"; js.async = true; sjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, sjs); }(document, 'script', 'storychief-jssdk'))

0 notes

Photo

The Color Purple (1985) dir. Steven Spielberg

Queering Black Patriarchy: The Salvific Wish and Masculine Possibility in Alice Walker'sThe Color Purple

Candice M. Jenkins

Family has come to stand for community, for race, for nation. It is a short-cut to solidarity. The discourse of family and the discourse of nation are very closely connected.

—Paul Gilroy, Small Acts

In her 1989 essay "Reading Family Matters," Deborah McDowell examines a pattern of hostile critical responses directed toward a "very small sample" of contemporary black women writers by some black reviewers and critics, mostly male (75). 1 McDowell describes the critical narrative employed by these figures as a black "family romance," the creation of a "totalizing fiction" of community wholeness—a fiction which, if realized, could rehabilitate a fragmented and painfully complex racial past (78). Gesturing toward the overwhelmingly masculinist ideology of black cultural nationalism, whose disciples she posits as the most powerful proponents of this family fiction, McDowell writes: "[T]his story of the Black Family cum Black Community headed by the Black Male who does [End Page 969] battle with an oppressive White world, continues to be told, though in ever more subtle variations" (78). Indeed, part of the increasing "subtlety" of such narratives is their extension into broader spheres of cultural influence than the putatively "political" arena, including the space of black literary production and analysis.

As McDowell goes on to note, Alice Walker has received more than her share of black (male) critical attack for disrupting this notion of family romance in her fiction; at least in part, that attack has been in response to the 1985 film adaptation of Walker's novel The Color Purple by Steven Spielberg, which brought a great deal of additional publicity to Walker and her work. Walker, accused by various critics of being unduly influenced by white feminists and of harboring animosity toward black men, seems to have written herself out of the so-called black family embrace, even out of the black community as a whole, by "expos[ing] black women's subordination within the nuclear family, rethink[ing] and configur[ing] its structures, and plac[ing] utterance outside the father's preserve and control" (McDowell 85). In other words, Walker's work (along with the work of such writers as Ntozake Shange and Gayl Jones, who have been similarly criticized) deconstructs a black family romance and represents unequivocally the ways in which "traditional"—and traditionally idealized—family structures can endanger black women both physically and psychically, largely because of the patriarchal power that such structures grant to black men.

Perhaps even more significantly, however, Walker's writing, and particularly her 1982 novel The Color Purple, also engages in a project of "queering" the black family, reshaping it in unconventional ways that divest its black male members of a good deal of power, thereby reconfiguring the very meaning of kinship for black sons, brothers, and especially fathers. 2 Indeed I invoke McDowell's essay, and the generally masculine critical furor to which it refers, at the opening of this essay on Walker's The Color Purple because I believe there are crucial connections to be made between the ways in which Walker's text calls for a queering or refashioning of family dynamics and the manner in which Walker herself, as author, has been scripted by a black (male) critical establishment as a delinquent daughter who has strayed from the black family fold. Not only do Walker's characters repeatedly find ways to subvert the shape and order of the heteronormative, patriarchal family, but in many ways [End Page 970] Walker's authorly body functions as an apparent source of subversion or betrayal in its own right, imagined by her critics to be waging treacherous assault upon a mythologically unified black community.

"Imagined" is, of course, the operative word in the foregoing sentence; nothing in Walker's published reflections on the filming (and resulting criticism) of The Color Purple suggests that her intention in writing this novel was to betray the black family/community. 3 Instead, what is at stake here is the behavior assigned to Walker by her critics, the motivations and loyalties she is assumed to hold, in short, the writerly persona grafted onto Walker's not-so-willing body by an act of critical storytelling. We might say, in fact, that Walker's writerly body is subject to interpretation in the same way that the narrative body of her fiction is. Indeed, the conclusion of "Reading Family Matters" cautions against the ways in which black women's "bodies" (in both senses of the term) might be reduced to the terrain upon which white and black men enact a struggle for power and control of the literary landscape.

While McDowell's point is well taken, my interest in drawing such a link between Walker's authorly body and the textual body of her novel is to call attention to a different set of issues entirely—namely, the gendered and sexualized complexities that underlie the black drive toward a patriarchal "family romance." The power of this drive, and the particular vehemence of critical responses to Walker, has to do with the manner in which patriarchy's hierarchalized kinship structure has generative consequences for black (hetero)sexual subjectivity—and particularly black masculinity. Disruptions of this kinship structure, such as those effected in Walker's novel, thus have the potential to unsettle black gender difference, even to render it incoherent. If, as Michael Awkward has suggested, "monolithic and/or normative maleness" is conventionally defined by the "powerful, domineering patriarch" (3), then a family in which men no longer dominate is a family in which masculinity itself is called into question.

This challenge to heteronormative masculinity is precisely why Alice Walker herself is imagined as a kind of racial turncoat for her portrayals of black men—not merely, as McDowell suggests, because these portrayals present black manhood in a supposedly negative light, or simply shift the focus of black fictional narrative away from the black male. In fact, it is the radical reshaping of the family effected in Walker's novel that [End Page 971] leads to her rejection by the black (male) critical establishment; Walker's transformative revision of black domesticity in The Color Purpleaccomplishes no less than the emptying of "black masculinity" as a term, insofar as that term has been dependent upon an assumption of black men's authoritative role in the family sphere.

In other words, Walker's refashioning of the black family "queers" the very notion of the potent black patriarch. Her text goes beyond simply representing an absent father, one who has abdicated from the legitimate seat of patriarchal rule; nor does it portray merely a father inadequately fulfilling the requirements of his (again, assumed rightful) authority. Indeed, both of these possibilities evoke what Sharon Holland, following Hortense Spillers, identifies as "fatherlack": "the idea of a dream/nightmare deferred [. . .] an inevitable and unattainable fatherhood" (387). For Holland, the cultural trauma of this lack—or the difficulty of fulfilling what Spillers names the "provisions of patriarchy"—is a "founding and necessary condition/experience of what it means to be black" (387). In this schema, the very concept of black patriarchy becomes a conceptual impossibility, precisely because of a fatherly absence contained within the cultural signifier "black."

I would differentiate the queered black father of Walker's novel from Holland's idea, however. Walker's subversive transformation of the black family, and of the black father, responds more to ahistorical fantasies of black patriarchy (erected, perhaps, as a defensive response to fatherlack), of which the black community harbors many. As Ashraf Rushdy notes, "African American intellectuals espousing black nationalism have long argued that the family represents the site for the development of the black nation" (109); for nationalists, "those families representing the race can form a nation only when [. . .] patriarchal power is evident" (110). Ultimately, it is in playing with, literally queering, such patriarchal fantasies that Walker's novel invites hostile critical scrutiny, for by the conclusion of the text, Walker's black family contains a possibility far more bewildering than the father's absence: a father who is present, but nonetheless no longer dominant or even interested in domination. It is no wonder, then, that Walker's narrative is viewed by many critics as an affront to black community wholeness, for it posits a community without a (male) leader, a masculinity without even the desire for what has traditionally been understood as masculinity's hallmark: power. [End Page 972]

READ WHOLE ARTICLE: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/21729

0 notes

Text

Project 3: Home is Where the Hiatt Is

Examples:

Moonlight Brokeback Mountain Mad Men The Simpsons (Abraham Simpson II) Rick and Morty The Secret Life of the American Teenager That 70’s Show Heteronormative greeting cards Preacher’s Daughters Every pop punk music video

Analysis and Campaign:

Throughout virtually all mainstream media, from reality television shows to songs, home is depicted in a nuclear, cisheteronormative, patriarchal way. These portrayals reflect the reality in which homes are the site of oppression for those who deviate from ideal norms. By presenting a standardized ideal of home, many people are ultimately excluded from experiencing the home as a safe and nurturing space.

Homes have historically been a symbol of property, not only in terms of land and material wealth, but also ownership and control over every aspect of the residence, including other occupiers of the house (Household servants, the unpaid domestic work of wives and children or the paid work outside the home by wives and children, all means of accumulating wealth in the name of the householder). A nuclear home allows for this type of control as well as the hoarding of wealth/property within the immediate family unit via inheritance. By media stubbornly insisting upon such unnatural arrangements and power structures, the hyper-individualism and consequent obsession with personal property ensure minimum class mobility, and thus broader systems of power imbalance are kept intact.

According to Valentine, “it is women who traditionally have been charged with the responsibility of making and maintaining the home, hence its characterization as a ‘woman’s place’” (Valentine, 63). Indeed, the home is historically associated with the “private sphere” and thus with unpaid labor. Within the context of the nuclear family, the wife is the person tasked with completing the unpaid domestic labor, while the husband works in the “public sphere.” In this sense, the home can be seen as a source of women’s oppression as it is the site of domestic unpaid labor.

According to Whitson, “the ideal of the home rests on a heterosexual norm; that is, homes are heteronormative spaces which are tightly associated with the nuclear family” (Whitson, 54). Because the purpose of the home is for women to raise their children through unpaid domestic labor, the home is ultimately a heteronormative space, as well. This concept is extremely pervasive throughout all forms of media, where any type of relationship that is not heterosexual and monogamous is evidently deemed “other” or “out of the norm.” Therefore, the ideal home ultimately excludes those who do not uphold the heterosexual norm.

Our posters suggest, by calling out problematic structures within the traditional home and therefore implying favor toward the opposite, that the ideal structure of the home would be thoroughly inclusive of all identities, and without assigning gendered nor unfair roles to any resident, and would function completely without patriarchal power structures. Moreover, a nurturing combination of community-care and personal agency would be foundational to this progressive space. This might include shared domestic duties, and shared care of children both within and beyond the household, as well as residency with and care of elders, without inhibiting the agency or dignity of any partially-dependent people.

As for the graphic design aspects, we tried to incorporate some of the thematic elements into our visual elements. The motto “Home is where the ______ is” is presented in a stylized manner, presenting a stylized mid-1900’s font not unlike the pseudo-authoritarian font Futura. The hand-drawn scrawl suggests dissent, specifically radical dissent in the form of violence against property. These ideas of shaking up the status quo go hand in hand with far leftist views of home as place and identity. This is expressed in the slogan’s play on a classic phrase, “Home is where the heart is”. By turning something culturally understood on its head, we’ve set the kind of sarcastic, coy, and playful tone we want the campaign to have. This connects back to the ironic use of 50’s imagery as a means of conveying our message. By appropriating the imagery of oppression, we can use semiotics to tap into the already learned iconography associated with the American home. While the campaign may come across as snarky, we believe it’s somewhat impish nature will play well for the target demographics.

For an official Ad Council campaign it may have a bit of a radical bite to it, but this is the kind of project we would like to see them run sometime down the line. The way they commonly tackle issues- especially drugs and smoking- can sometimes have some edge to it to appeal to younger folks. Having fun with the designs was a key reason we think they work- this is a campaign aimed at the upcoming generations who will be in a position to change the problematic views of home.

0 notes

Text

preface: during this thing I use queer as an umbrella term for the broader LGBT community and wlw (woman loving woman) when specifying a subsection of woman aligned people who are attracted to other women which can encompass lesbian, bisexual, pansexual identities as well as woman aligned people on the aromantic spectrum and asexual spectrum who experience same gender attraction of some measure.

On a Sunbeam by Tillie Walden is a sci-fi webcomic (2016-2017) set an unknown but far way into the future where the galaxy has been colonized by people. Mia, a young woman, starts on a new job with a crew of four construction workers who travel into the long forgotten reaches of space and restore old buildings. Through this the reader learns about the crew and follows the present day actions. Simultaneously Mia’s story of growing up is told, as she goes to boarding school and meets Grace, a girl whose family controls part of the most dangerous places in space, the Staircase. Through these two parallel stories you see Mia and Grace’s relationship develop in the past, while in the present Mia struggles to find Grace on Staircase again.

On a Sunbeam is told in two parts. These two threads are interwoven and eventually come together with Mia going to Staircase and finding Grace. The parallels in these two opposing story lines speak to greater critical ideas that exist within queer theory. Although Walden has created a universe where every single person (with the exception of Elliot) identifies as a woman and every known romantic relationship is with another woman, the before and after aspect of queer identity is still present. This way of presenting narrative and the narrative arc itself strays from traditional storytelling, two stories existing, two separate identities the reader gets to know, both existing in tandem. The entire comic ends with Mia’s reconciliation of identities, with finding Grace and looking for some resolution to that chapter of her life. This is a common theme among coded queer fiction, the split identity or the journey from one world to another. When one examines sci-fi fantasy through a queer theory lens this is one of the ways queer themes can exist.

In science fiction the idea of Other is key. In cases involving alien races or new customs, or even futuristic technologies, when creating a fictional Other, that will be rooted in our cultures concept of Other. In this case unlike a lot of science fiction there is no masquerading an unknown entity as an Other, but this concept is now given to us, the reader to process what is like, and unlike our culture now, which is what defines science fiction essentially.

One interesting feature of On a Sunbeam is the fact that it is specifically not diverse. Every character in this webcomic (again barring Elliot who is gender neutral) is assumed to be a woman, and every discussed romantic relationship is gay. This brings in the idea of the reader creating the science fiction, and creating the Other, reconciling differences between our world and the fictional world.

On A Sunbeam is pointedly not inclusive in respects to sexuality and for a reason. Walden’s comic speaks of separatism and the specific catering to a wlw (woman loving woman) audience, a lesbian only piece of media leads to the lesbian Separatist movement that emerged in the 70s, where the idea was to be self-sufficient and independent from a patriarchal society. Lesbian only spaces are a form of resistance against the heterosexual institution.

Through this Walden points out the heteronormativity of media where queerness has to conform to an idea of reality. When consuming media it’s not a surprise to have an all straight cast of characters, it’s not questioned at all. Opposed to when the majority (or even a portion) of the characters are queer it is immediately noticed and the rules of “reality” are applied, whether having that many queer characters is realistic, especially in a narrative that is not a typical gay narrative. It is rare to find media where every character is queer opposed to finding a mass amount of media where every single character is straight. Side note if I have to hear that the diversity of a piece of media is just trying to reflect the world's demographic then clearly I’m missing the statistic that said that most of the world is white, everyone is gorgeous, and vampires and werewolves are better represented than trans people. GLAAD’s 2016 report of LGBTQ representation sits at 4.8% of characters on primetime television which is 43 characters out of 897. So my point here is that we can have this enormous mass of straight characters and not question it which is a direct result of heteronormativity. Only having wlw characters is a direct challenge of the heteronormative structure of the media we consume, and by doing this Walden asks readers to acknowledge this, the immediate discomfort with the unexplained fact that every single known character in her comic is a wlw and consider it rationally.

Why are queer identities a feature of science fiction? Why is one of the things that is striking not the fact that there are space ships that are giant robotic fish, or that there is a place called The goddamn Staircase which has glowing giant fox beasts in it. Where does the true other lay? Not in the world we live in entirely, but where we see ourselves fit in. Ain’t that poignant enough for y’all.

Last point my man. The theme of family and community is prevalent in queer media too because so much of queer identity (or at least what media leads us to believe) is about acceptance. Acceptance into the community around (be it the general community or the LGBT one), acceptance into ones family, or acceptance into the greater world. Found family comes into play in many queer stories in opposition to biological family, “The blood of the covenant is thicker than the water of the womb” maybe?

The dynamic between Mia and the team on the ship and Grace and her family demonstrates this concept pretty accurately. This plays into the idea of building a community which can be more supportive and healthy than the community one is born into. This is really part of the queer identity because unlike some other intersecting identities as a queer individual you aren’t typically born into a queer community, you go and seek out one, or build one yourself. Part of being queer is trying to find other people who are queer and building a network of individuals who aren’t necessarily blood related but feel like family. This also can be coupled with the rejection of the patriarchal structure of the nuclear family, which plays directly into queer identity, which is inherently aberrant and maladjusted to fit into the heteronormative idea of it. The whole story, of two wlw girls who meet when they are separated from their families, in an institution which they both don’t fit into and get into trouble because they can’t conform and find companionship because of their isolation and dissatisfaction speaks to the reality of living as a queer woman.

Anyways that’s my analysis! On a Sunbeam is written by Tillie Walden who is is super bomb and very great for letting me use these images

0 notes

Text

Uma Kotwal, ‘Turfing out the TERFs’

Uma Kotwals’s recent talk for Warwick Pride LGBT+ History Month explored the conflict between trans erasing radical feminism (TERF) and trans women.

Debunking the myths

Many radical feminists are not transphobic; many are themselves trans. However, there is some radical feminists regard trans women as a threat to feminism. Kotwal explored this trope through certain themes.

Gender essentialism

Radical or gender critical feminists often argue for reframing activism beyond the heteronormative gender system (sometimes referred to as gender nihilism). Some see in trans women a form of gender essentialism and reinforcement of gender roles.

Kotwal acknowledged that some trans women are reinforcing gender roles, but so are cisgender women. Gender still has a bearing on our lives. Trans women may have to perform femininity in order to access medical treatment, legal recognition and social recognition.

Much TERF ideology reinforces binary concepts of gender and is itself gender essentialist. For example, some radical feminists have argued against anti-discrimination protections based on gender identity in favour of anti-discrimination protections based only on sex. Some have expressed discomfort with the term ‘cisgender’, arguing that as gender is entwined with sex it is a moot term. However, Kotwal argues that this risks reducing womanhood to sex characteristics and reinforcing binary gender roles.

Coercion of children

Against the argument that gender (role) non-conforming children are being coerced into identifying as trans, Kotwal argued that trans children are often coerced to act according to their sex assigned at birth.

Male privilege

Against arguments that trans women experience male privilege by virtue of often being born with a penis, Kotwal argued that the experience of trans women is different to that cisgender men. Trans women are often very disempowered in society and experience higher rates of violence.

The penis is not inherently male or masculine; people of all genders have penises. Male power or domination does not arise from the penis, it is socially constructed. Women’s oppression is not based on sex characteristics but on gender.

Lesbian and bi women

Capitalism/nationalism

Lesbian and bi relationships are sometimes seen as a threat to the nuclear family. The reason the nuclear family structure is privileged under capitalism is because, as Christine Thomas writes, “Capitalists also required a workforce that was disciplined, obedient and deferential to authority. The patriarchal family, in which men had control over women and children, including through the use of physical violence, was a useful institution for instilling these values and for promoting appropriate gender roles.”

Furthermore, as Cheshire Calhoun writes, “The construction of gay men and lesbians as highly stigmatized outsiders to the family who engage in family disrupting behavior allays anxieties about the potential failure of the heterosexual nuclear family by externalizing the threat to the family. As a result, anxiety about the possibility that the family is disintegrating from within can be displaced on to the specter of the hostile outsider to the family.”

(However, I would argue that the emergence of rainbow families suggests that lesbian and bi women have a new utility to the capitalist state. This phenomenon has sometimes been referred to as homonationalism.Related to this are nationalist colonial discourses that portray non-Western LGBT+ women as disadvantaged. These discourses ignore the fact that non-binary women are recognised in some non-Western countries.)

Predatory behaviour

Pointing to the trope of ‘queer woman converts younger heterosexual woman’, which appears in novels and films of lesbianism, Ruby Lott-Lavigna argues that “converting the straight girl... is cinema’s idea of how the lesbian relationship functions.” This effectively portrays lesbian and bi women as coercive when, in reality, lesbian and bi women are often frightened of pursuing other women and can be subjected to homophobia or biphobia in shared women’s spaces.

Lesbian and bi TERFs

However, Kotwal noted that some cisgender lesbian and bi women are also TERFs and do use anti-phallus rhetoric against trans women. Lesbian and bi trans women can experience exclusion from other lesbian and bi women and spaces. As Avory Faucette writes, “You’re confused about what it means to be a lesbian, or a woman. I don’t care what your physical preferences are or what gender identity you prefer. I do care that you confuse those two things, and thereby insult trans women. I care that you don’t bother to interrogate the origins of your phallus-based distaste for trans women, and think about whether it’s actually a dislike of the organ that’s happening here or whether transphobia and a refusal to view trans women as women is involved.”

Re-thinking terminology

In an effort to be inclusive of trans and non-binary people, some organisations have started to use the term ‘non-men’ in the place of ‘women’. Some feminists have argued that this is effectively erasing women.

Kotwal argued for a language of womanhood that is not based on sex characteristics, and for a social rather than biological definition of (female) gender. She did acknowledge, however, that female sex characteristics do affect many women - they experience periods and experience discrimination on the basis of their sex characteristics (President Trump’s “grab her by the pussy” remarks being a case in point) - but should not be the sole definitional point for womanhood.

Ways forward

There are, unfortunately, transphobic academics and public intellectuals, including at University of Warwick. There are also, however, risks in no platforming or protesting TERFs as this is commonly raised as an attack on free speech.

Kotwal argued for the importance of talking about and understanding the everyday experiences and issues of trans women. The Museum of Transology is one example of this. Trans women need feminism and feminist spaces due to the misogyny they face. Trans women played and important role in Stonewall and continue to play an important role in the ensuing now global pride festivals; this should be recognised.

It is our responsibility to make feminist activist spaces and language explicitly welcoming to LGBT+ women.

0 notes