#the in game sequence to discovering the temple and entering it to the music made me so nostalgic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

To the temple in the woods

#loz#legend of zelda#twilight princess#loz tp#link#that’s where we are headed#the fucking temple of time#now I know this is not what the way looked like in the game#and at this point link has the Hylian shield and master sword#I spliced a whole lot of references for the vibe the journey had#not accuracy#the in game sequence to discovering the temple and entering it to the music made me so nostalgic#I definitely cried a lil

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jet Li - China’s Hero

By Sam Cave

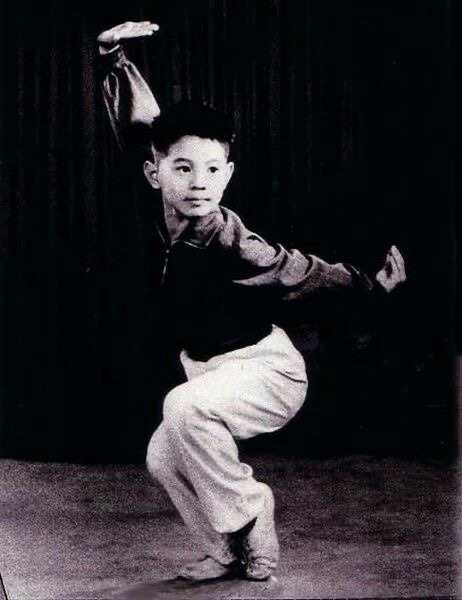

Beijing, 1963. A child is born into poverty, the youngest of five. By two years old, his father has passed away. His family can’t afford meat, so young Lie Liajie is often hungry but never complains. When he is eight years old, his mother enrolls him in a summer course for martial arts. He shows a natural talent for Wushu, and his instructor takes notice. The boy attends a non-sparring Wushu event. Soon after, the instructor refers him to Wu Bin, coach for the Beijing Wushu Team. With his family’s permission, he is allowed to join. The coach takes a special interest in the boy, making him practice twice as hard as the other students. The criticism is harsh and constant, but he has good to food to eat and a sense of purpose that will help him to rise above his environment - China’s rocky crossroads between the Great Leap Forward and Mao’s cultural revolution.

A few years pass. Once a year the team is allowed to go to the movies. They watch Shaw Brothers and Shaolin five venoms, and sometimes Jimmmy Chang. One night the team gets to see a film called Fist of fury, Starring a westerner name Bruce Lee. the older boys love the film, and they clap and cheer, some of them smoking cigarettes and drinking rice wine. Their instructor chaperones hush them but also smile and laugh. Even as strict as the coaches can be, these boys need to blow off steam. The boy sits and watches the film, wide eyed. A friend passes him a Coca-Cola but he doesn’t notice. He is mesmerized by Lee Little Dragon’s screams and whoops, his speed and tempo. It is not so much Bruce Lee’s skills - the boy has seen Wing Chun and Southern Style Kung Fu before many times. It is the pauses, the stare, the speed with which he executes each maneuver. These are the things that a young Lie Lianjie would incorporate into his own fighting style, as the years ahead transformed him into the Martial Arts idol in known as Jet Li.

Asian cinema is a vast genre, with very different subsets. When I think of Japanese film, I picture ghost stories and bloody action like The Grudge or Battle Royale. Korea has the darkly comic revenge films of Chan Wook Park (Oldboy, Lady Vengeance). John Woo (Hard-Boiled) and Wong Kar Wai (2046, In The Mood For Love) both hail from Hong Kong. Historically, Mainland China’s identity in film has been firmly rooted in martial arts and Wushu-style historical epic tales. This makes sense, since the Wushu novels of writers like Jin Yong hold a place not unlike Tolkien in Chinese literary culture. Jet Li’s characters in Once Upon A Time in China, Fist of Legend and Fearless are based on real historical figures, and the China depicted in these stories is an honorable, decent place worth fighting for. The nationalistic message is often heavy-handed, but considering the China of twenty or thirty years ago, perhaps people needed to believe in not just heroes, but Chinese heroes.

I first discovered Jet Li when I saw Lethal Weapon 4. He played a silent martial arts villain with a ponytail who could dismantle a gun in seconds. His pre-combat stare was like nothing I’d ever seen onscreen before. It is his trademark - when he glares at his enemy he eminates both pure calm and pure danger. LW4 was Li’s first time crossing over into American films, after making over 30 movies in China since his debut in the 1980’s. Becore Jet Li started acting, there was an effort to find a successor to Bruce Lee, as evidenced by the early films of another Chinese martial artist, Jackie Chan. Chan was ten years older than Jet Li, and had been trained at the Chinese Opera. By Contrast, Li’s training focused purely on martial arts. He specialized in Wushu from the age of eight. Unlike Bruce Lee, who broke with Kung Fu tradition to establish his own style of fighting, Jet Li would become a Kung-Fu formalist. His trained at the Shao-Lin temple and spent years becoming an expert in Northern-style Kung Fu. Before the age of 10, Li won gold medals at the All China Games, and his team performed for Richard Nixon at the White House. According to Wikipedia:

he was asked by Nixon to be his personal bodyguard. Li replied, "I don't want to protect any individual. When I grow up, I want to defend my one billion Chinese countrymen!"

Jet Li would not be groomed as Chan was, to carry on Bruce Lee’s legacy. Too much time had passed and the industry had moved on from Bruce-sploitation and the legacy of Enter the Dragon. When Li first emerged in the 1986 film Shaolin Temple, his Northern Wushu and Tai Chi background was evident in every move, every trap, every aerial spinning kick. His fighting and performing style harkened back to old-school Kung Fu films by Shaw Brothers like Five Venoms and (bla).

…

The storyline of a typical Jet Li film goes something like this: A guy from mainland China (cop, soldier, fill in the blank) is tasked with the responsibility of protecting someone or exacting revenge for a dead master. He goes to Hong Kong, Japan or America, where his upstanding and honorable values are called into question by his new surroundings. There’s a girl, a villain, and much flying of fists and feet until finally the hero returns to China, happy to be home (in The Defender, he is killed and his body goes back to China).

After a few years as a supporting, utility player, Jet Li got the role of a lifetime playing Wong in Once Upon A Time in China. The film, directed by Tsui Hark, was a retro/throwback style historical epic with sharp cinematography and high-flying wire assisted wushu fight choreography and stunts. It was a leap forward for Hong Kong film, and spawned 3 sequels with Li reprising the main role. The films that followed could be described as Jet Li’s Hong Kong period. Fist of Legend, The Defender (also titled Bodyguard from Beijing), The Enforcer, Meltdown, Hitman, Tai Chi Master, Swordsman series. The list goes on.

Some of these movies showcased Li’s martial arts skills better than others. Sometimes he had guns, like Chow Yun Fat in Hard Boiled. Sometimes he had a kid sidekick or a love interest. One thing is for sure - playing in a Hong Kong action movie in the 90’s was not for the faint if heart. Cut-rate action techniques and low-budgets loaned themselves to accidents. The fighting was often full-contact. Actors could end up with a face full of glass from explosions. Still, the Beijing Wushu prodigy found his place amongst other martial artists like Donnie Yen and Michelle Yeoh, churning out epics, gangster films and cop dramas for audiences in Hong Kong (now hurtling towards its handover to the mainland) as well as the rest of Asia and beyond.

The only unfortunate aspect of Jet Li’s Chinese catalogue lies in the poor production values of most of these films. The overdubbed English is poorly translated, the action has a cartoonish quality and the characters are usually stock and cheesy. In other words, they are typical ‘Chop-Socky’ Kung Fu films made in the style of Bruce Lee’s catalogue, before the technical achievements of later films like Crouching Tiger, Hideen Dragon and Iron Monkey. There are some clear exceptions, such as the Once Upon a Time in China series, expertly directed by Tsui Hark and featuring another Kung Fu prodigy, Donnie Yen.

Because they were made before the age of DVD and HD, Li’s films could only be seen by Western audiences in rare Chinatown screenings in a few major cities. In the late 1990’s a new pop culture trend would change this pattern, and the trajectory of Li’s career – catapulting the Wushu prodigy from China to the United States. When Wu-Tang Clan first arrived on the American hip-hop scene in 1993, no one was prepared. Their albums were soundscapes comprised of hard-hitting verses, skits, and samples from Kung Fu and martial arts films. Along with Nas, DMX and others, Wu-Tang popularized Jet Li’s films by referencing him directly in their music. Li noticed, and his late 90’s output reflected this unlikely alliance. Black Mask, Romeo Must Die, and Cradle 2 the Grave featured Li’s action sequences cut to high-energy hip-hop. The films were successful, proving that Jet Li’s Wushu could be imported to the West.

Like Jackie Chan, Jet Li’s late 90’s crossover into Hollywood films was inevitable. It was a career move probably not based on financial need (he was already wealthy), but more based on the fact that he had outgrown the Hong Kong film scene. After his role in Lethal Weapon 4, he starred in a string of ambitious but fairly crappy vehicles like Romeo Must Die, Kiss of the Dragon, and Cradle 2 the Grave. These films, though largely panned by critics, served the purpose of greater exposure to US audiences and access to directors and filmmaker

In 2006, Jet Li announced his retirement from martial arts movies. The final entries into Jet Li’s martial arts catalogue, all made around this time, are easily the best. Hero, Unleashed, and Fearless are examples of bigger-budget Jet Li, not so different from his Chinese films but with an emphasis on acting and emotional content.

Hero is an epic historical tale in the style of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. In the film Li plays Nameless, an assassin tasked by an Emperor to eliminate those warriors perceived as threats to his his throne. Filmed in wild and beautiful colors with flawless cinematography, Hero is an example of contemporary Chinese cinema, and how much technical ground has been gained in the past 15 years. The film has been hopelessly replicated and borrowed from since its release in 2002, mostly due to its historical accuracy, dark tone and operatic fight sequences. It was at the time the most expensive mainland Chinese film ever made, and sits at the beginning of a trio of martial arts films by director Zhang Zimou, who before Hero was mostly known in art house circles for his dramatic collaborations with actress Gong Li.

The casting of Hero was an eclectic mix of non-martial artists and experts, with Jet Li (the mainland’s biggest star) in perhaps his biggest starring role to date. Donnie Yen, who at that time was still a supporting player, was brought in for the first fight scene. Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung, coming off the huge success of Wong Kar Wai’s In The Mood For Love, played the feuding lovers Broken Sword and Flying Snow. And Crouching Tiger’s Ziyi Zhang played Moon, the loyal servant. Leung and Cheung were both veteran Hong Kong actors, neither one from strictly martial arts but with 20 years of experience in all genres. Zhang came from a ballet background, and though she had a breakthrough performance in a Crouching Tiger, her martial arts skills were limited. Jet Li recognized her talent and mentored her on set, and joked about his short legs being the reason for his never trying ballet. It made sense for Li to reach out to the younger Zhang, also from the mainland and twenty years his junior. For so long he himself had been the young Wushu prodigy, but now at over 40 years old he was sliding into an elder-statesman role.

The action sequences in Hero used wires extensively - not just as a tool to exaggerate aerial jumps and spins but to make the characters fly and soar the air, dreamlike and surreal. This deliberate wire choreography may have been influenced by The Matrix and Crouching Tiger, but Hero has its own sort of Cecil B DeMille outrageousness to it that is totally out of balance with the serious tone. In fact, Hero is almost weighed down by its own sense of gravity, and is sometimes unintentionally funny when it’s adding more and more layers to each action sequence. (Arrows). It is here that Jet Li is the films saving grace. His sense of form, toughness and his skill not just as a martial artist but as an actor corrects the balance. When Li extends both arms in front of his face and slides his sword back into its sheath with a resounding and satisfying ‘click’, the film resets itself and we, the audience are given a break from the proceedings.

Unleashed raises a poignant question: can a man who has been reduced to an animal find salvation? In this film Jet Li plays Danny, a childlike soul with violent tendencies, trained since childhood to fight and kill on demand. His aggression is symbolized by a metal collar, which is controlled by his brutal ‘master’. Li is passive until the collar comes off, at which time he becomes an attack dog, dispatching his opponents in a flying, screaming rage. Unleashed is pure pulp, but it is elevated by the presence of Morgan Freeman (as Danny’s kind savior), and by Jet Li’s performance. Danny is a kid, full of wonder and innocence, but unable to escape the violence that has defined his existence. Li plays it with subtle, quiet emotion and dignity. The action in Unleashed is as usual exciting and well mounted, choreographed by longtime collaborator Yuen Woo Ping. There are even some darkly funny moments, like when Danny kills an opponent with one poke to the Adam’s apple. Yikes.

Fearless is an atypical Chinese martial arts film, because it shows the hero as lacking virtue (at least for the first half of the film). Li plays Huo Yuanjia, Godfather of Wushu and undefeated champion of Tianjin. After murdering a rival in the ring, the rival’s disciple takes revenge and kills Huo’s family. In his grief, Huo goes into exile and lives amongst simple farmers. Finally he returns home, humbled but also disgusted by the imperialist influx of foreigners taking over China. He begins to fight again, but this time for the honor and reputation of China – essentially for China’s place in the world. His final fight before dying from poisoned tea is against Tanaka, a Japanese samurai. It is worth noting that the Japanese occupation is a common theme amongst Chinese and Korean films. Both countries suffered under Japan at different times, and in the world of Fist of Legend and Fearless (two parts of the same story) the scars are still fresh. Fearless is actually titled Jet Li’s Fearless, and this film finds the actor back in his comfort zone of pure Wushu action and Chinese history. Where in Fist of Legend he reprised Bruce Lee’s performance in Fist of Fury as Chen Zheng, student of Huo Yuanjia and avenger of his master’s death, Li gets to play the master himself. Fearless is a mainland production, not as artsy as Hero and more in the vein of Once Upon a Time in China.

In the wake of Bruce Lee’s untimely death, the martial arts world was fractured. In the West, Karate was gaining speed and this popularity gave actors like Chuck Norris (a contemporary of Lee’s) and Jean-Claude Van Damme

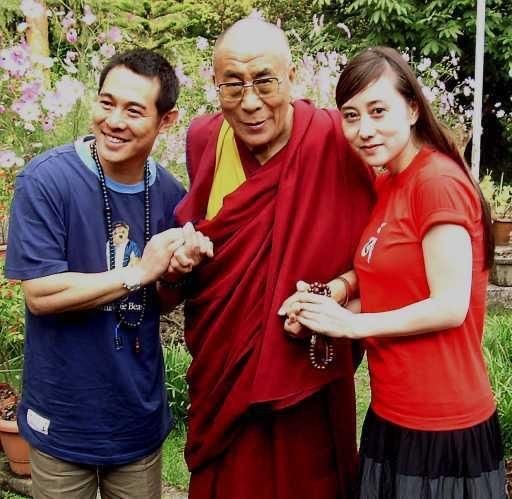

It would seem the sun has set on Jet Li’s career. He left his audience wanting more, and with Disney hinting that he might return to his martial arts roots in Mulan, there may be more to see. In his personal life, Li occupies the rare position of the a mainland Chinese with wealth, who, now living in Singapore, is somewhat beyond the reach of the communist government. As a devout a Buddhist he has in fact visited the Dalai Lama (while making sure to voice his belief in a united China). He

So, the question remains. What is your favourite Jet Li movie? And why does Jet Li Matter? In the opinion of this humble critic, Jet Li Matters because China matters. Mainland China needed a hero during times of extreme transition, when the Western idea of the Middle Kingdom was that it was a place that manufactured plastic trinkets. Audiences got used to Jet Li, Michelle Yeoh, and yes, Jackie Chan - as the heroes of Shao Lin or daring Beijing Police detectives, fighting their way through low-budget films made by an industry trying to keep up with the world, yet not afraid to have some fun in the moment. I still have only seen a handful of the original Jet Li movies, and so my perception of his work is top-heavy, weighed down by the performances from the end of a unique and amazing career. But what performances they are: Danny the Dog sitting next to Morgan Freeman at the piano, trying to find the courage to say his own name. Nameless and Flying Snow deflecting a sea of arrows with their swords, weightless in the air above a temple. And finally Huo Yuanjia, in the last moments of his life and with poison coursing through his veins, finishing his battle against Tanaka, Japan, Imperialist Britain, and himself. Jet Li Matters.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on http://www.classicfilmfreak.com/2017/05/18/the-most-dangerous-game-1932-starring-joel-mccrea-and-fay-wray/

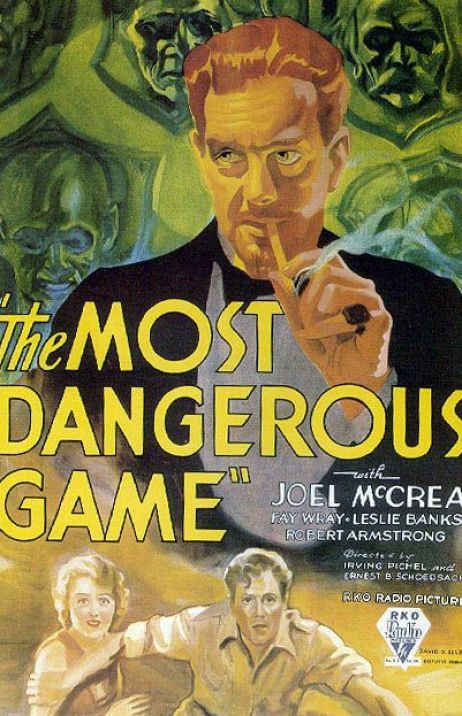

The Most Dangerous Game (1932) starring Joel McCrea and Fay Wray

Count Zaroff is an avid hunter, but exactly what he hunts is rather unique, as his guests soon discover.

Aside from both being horror films, King Kong shares numerous similarities with The Most Dangerous Game, released the year before in 1932. Both are produced by David O. Selznick, then head of RKO. Both are scored by Max Steiner. Both utilize some of the same sets, most strikingly the large one for the jungle. Both films star Fay Wray and Robert Armstrong in leading roles and a number of now forgotten supporting players, Noble Johnson, James Flavin, Arnold Gray and Steve Clemente, in minor parts.

The theme of The Most Dangerous Game, man hunting human beings for sport, is based on a short story by Richard Connell in a 1924 issue of Collier’s magazine. Connell (1893-1949) went to Hollywood and quickly became a screenwriter, most impressively for Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe (1941) and Two Girls and a Sailor (1944).

Presented at least three times as a radio drama, The Most Dangerous Game first appeared as an episode of Suspense, September 23, 1943, with Orson Welles as the notorious man hunter Count Zaroff, and Keenan Wynn as the American big game shooter.

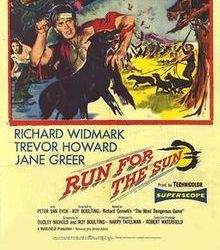

Following 1932, the theme of Connell’s story surfaced in, first, two films of sharply contrasting quality. In A Game of Death (1946) an undistinguished cast, providing undistinguished performances, helps make a surprising dud for director Robert Wise. Much better, perhaps even superior to the ’32 Game, with a few additional plot twists and a more developed love story, Run for the Sun (1956) throws Richard Widmark, Trevor Howard and Jane Greer into the jungle. Now the chief villain is a Nazi.

In the next film incarnation of the man-hunting-man subject, Bloodlust (1961), it’s teenagers who become prey for a wealthy recluse. Then followed John Woo’s Hard Target (1993) with Jean-Claude Van Damme, Surviving the Game (1994) with Rutger Hauer, Pest (1997), a comic, bottom-of-the-barrel take on the story with Jeffrey Jones, and, most recently, The Eliminator (2004).

In any synopsis of The Most Dangerous Game, it would seem proper, even necessary, to include a running commentary on Max Steiner’s score. The music plays an integral part in the film, an equal participator, especially in the long jungle chase, where, with minimal dialogue, there is only the screen and the music.

The composer’s contribution here, coming in 1932, is early in the evolution of the extensive, nineteenth century style score that would, by the late 1930s and the further achievements of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, become standard procedure. King Kong, made at the same time as Game but released a year later, the delay owing perhaps to the time-consuming special effects required for Kong and the prehistoric creatures, has one of the first continuous, wall-to-wall scores in sound-on-film movie history.

Though music for Game occupies only about half of the film’s running time, the one sequence in the chase that lasts over four minutes demonstrates not only the competence and confidence of Steiner at this rather early stage in his film-scoring career, but shares a similar ambiance with the music he was simultaneously writing for King Kong. The composer would not reach his artistic peak until he joined Warner Bros. in 1936, beginning with The Charge of the Light Brigade, his inaugural score for that studio.

The main title is distinctive for the great iron door, and, unfortunately, the rather incongruously shy hand (why not a dramatic, insistent one?) that three times lifts the knocker, each timid knock bringing a new wipe of credits. First heard after the RKO telegraph-tower-atop-the-globe trademark is an ominous two-note motif on a solo horn, alternating with an uneasy disturbance in primarily the strings. Rather than the door opening, there’s a last wipe for a listing of the players.

The sinister music of the main title segues into a contrasting, soft lyrical theme, reminiscent, seven years later, of Steiner’s Dodge City score. On screen, it is night and a yacht is navigating a channel on the west coast of South America, guided by lights from several buoys.

The captain (William Davidson) is concerned that the location of the lights disagrees with his charts, but big game hunter Bob Rainsford (Joel McCrea) persuades him to sail on. The yacht runs aground and quickly sinks. After two companions are eaten by sharks, Rainsford swims alone to an island.

After wandering through the jungle, he approaches a fortress-like edifice and knocks on the huge entrance door (from the main title). The door slowly opens and he steps into an enormous room as the score fades. A bearded man (Johnson) behind the door pushes it closed. Dressed in a white tunic, he doesn’t speak when Rainsford quizzes him.

Descending a long flight of stone stairs, a man in a tuxedo and smoking a cigarette on an extender says his servant, Ivan, is dumb. He introduces himself as an expatriate Russian, Count Zaroff (Leslie Banks in his talkie début). During World War I, the left side of his face was scared, an injury he adapts to his screen personas—for good guys, the left side is away from the camera; for villains, that side is toward the camera. Here he openly refers to the scare—“this head of mine”—and frequently touches his fingers to the mark on his temple, a sign of insanity, perhaps?

Rainsford meets two other guests of the count, Eve Trowbridge (Wray) and her inebriated, blasé brother Martin (Armstrong). Both, the count announces, were also stranded by a sinking ship. Eve seems to subtly warn Rainsford that things aren’t right here.

In the course of the evening, the four discuss the fine art of hunting. “Here on my island,” Zaroff says, “I hunt the most dangerous game.” “Tigers?” Rainsford asks. The count touches his temple. “My one secret. I keep it as a surprise for my guests, against the rainy day of boredom.” (The last phrase is a bit uncolloquial, clearly a writer’s line.)

After Rainsford and Eve retire for the night, the count offers to show Martin his trophy room. “I’m sure,” Zaroff says, “you’ll find it most . . . interesting.” (First time that adjective was used so ominously? Perhaps not!)

After almost twenty minutes of absence, Steiner’s score returns as Rainsford, from his bed, hears the sounds of dogs and a knock at the door. Eve says her brother is not in his room. The two creep downstairs, accompanied by stalking double basses and, at one point, the horn motif, now buried in the orchestral texture. Inside the trophy room, they behold a human head mounted on the wall. (Other heads and some gruesome dialogue by Zaroff were deleted after the premiere.) The count, carrying a candelabrum, enters with two servants bearing, on a stretcher, a dead Martin.

Now Rainsford learns which game Zaroff hunts, that Martin was his latest prey and that the madman has shifted the buoys to strand ship passengers on his island. By refusing to join the count in future hunts, Rainsford now becomes the hunted, provided with a woodsman knife and from sunset to sunrise to survive. Eve, rather than stay behind with Zaroff, joins Rainsford. The count himself won’t start “hunting” his two prey until midnight.

Rainsford first sets a Malay dead-fall or man-catcher, but Zaroff triggers the trip line with an arrow from his Tartar war bow, causing the dead tree trunk to fall harmlessly.

Next, a pitfall, with branches and brush over a crevice, fails to snare their pursuer. When Eve and Rainsford slip into a fog bank, making Zaroff’s rifle ineffective, the mad hunter signals on a hunting horn—the two-note horn motif from the score, no less. His dogs (Great Danes) are released, with Ivan holding the leashes to three or four of the animals.

Rainsford, at one point, sticks a sharp-ended branch in the ground, and Ivan is impaled upon it, leaving, now, Zaroff and only one servant in pursuit.

While most of the chase is music-accompanied, there are several long stretches where Steiner’s presence comes forth brilliantly. He gives the brass an amazing workout, especially the trumpets; the horn motif is sometimes heard as a solo, sometimes buried in the fabric of the orchestration. Much of the scoring, however, is standard action music, full of ostinato rhythms and various motifs in addition to the horn call, a montage suitable for any kind of chase, though nonetheless exciting. Some classical music “purists,” whoever they may be, would denigrate it out of hand as, “Oh, this is just film music,” as if that fact made it an automatic negative.

The chase climax, in screen action and music, occurs behind a waterfall. Rainsford kills the first dog, but Zaroff shoots and Rainsford and the second dog, locked in a death struggle, fall into the plunge pool of the falls. With a dramatically lighted close-up with deep shadows, the count’s eyes glare as he takes Eve back to the fortress as his prize. “Only after the kill,” Zaroff had said at the beginning of the hunt, “does man know the true ecstasy of love.”

The supposedly triumphant count now plays a waltz on his piano, a Steiner tune containing, persistently, the horn motif. Soon after Zaroff asks a servant to bring Eve to him, he is confronted by Rainsford, who says he took a chance and fell with the dog; it was the dog the count shot. Zaroff admits defeat, tossing the keys to the boathouse, but then pulls a pistol from a table drawer. The two men struggle, accompanied by Steiner’s fight music, and Rainsford stabs his opponent with one of his arrows. Even as Eve and Rainsford are fleeing in the motorboat, the wounded count staggers to a high window with his Tartar war bow, but dies and rolls out the window before he can shoot.

The small cast generally renders convincing performances, especially Joel McCrea, always excellent as the stalwart man of intelligence, and Fay Wray as the damsel in distress. For the chase, her nightgown attire, hardly improper today, would have been deemed too risqué if the then in operation Production Code had been doing its job, though strict enforcement did begin in 1934. There are no moments for an authentic romance between the two leads, so tied are they to the plot of their staying alive.

Armstrong often overacts, especially when he’s playing drunk. It’s hard to know whether he is the standard one-note comic relief in a generally humorless film or a bona fide actor trying to be serious. He may well be the weakest link among the leading stars.

Leslie Banks is the standout, if for no other reason than he, too, overacts, a little campy, but that somehow colors his identity as a suave, cultured villain. His Shakespearean training, with the somewhat old-fashioned cadenced tones, is misplaced, at least in this case. In Laurence Olivier’s Henry V (1945), he is relegated to being the chorus.

A MUSIC NOTE – For those interested, the excitement of both the film and the music may be “relived,” so to speak, through a NAXOS CD (8.570183), the only modern (2001) recording available of the Most Dangerous Game score. The disc is highly recommended for the excellent playing of the Moscow Symphony Orchestra, the sound engineering by Edvard Shakhnazarian, the extensive notes by Bill Whitaker and a generous thirty-two minutes from the score. Also included are forty-five minutes from another Max Steiner score, the 1933 Song of Kong, the sequel to King Kong.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_DXLTw22HOQ

0 notes