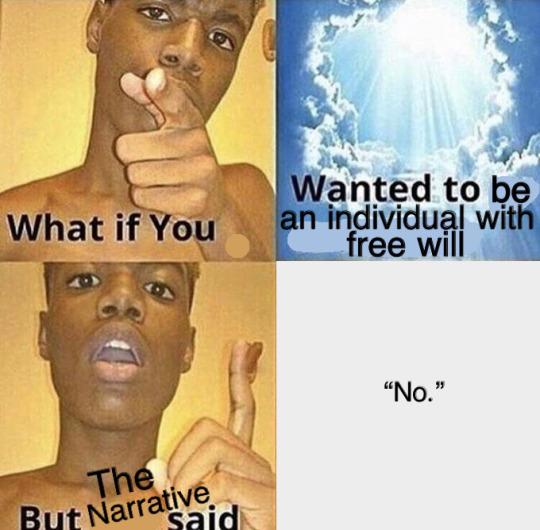

#the idea that characters must concede their very humanity to The Narrative is so brutal and horrifying and i’m in love with it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A review of Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

This was a really disappointing book. It’s on so many 100-best-books lists, but who is putting it there?

So first, the good: clearly Heller had ideas. The titular idea — that one must do X before one can do Y, but simultaneously must first do Y before one can do X — is clever. I concede that. Additionally there are a few humorous episodes, such as the story of Major Major, and character arcs, such as the chapters about Milo Minderbinder, where I can see the author’s satire and I think it’s effective. Surely this struck a nerve in the 60s, when McCarthyism was in recent memory, and awareness and skepticism of the military-industrial complex was growing. Also I admit the last 40 pages or so were quite riveting, where Heller lays on the human pathos with a knife, and you get Hieronymus Bosch levels of debauched brutality and visceral emotional scenes, and I was very into that.

Now, the bad: The book is unbelievably sexist. Every single female character, without exception, is a 2-dimensional sex object, only on the page to have sex with our hero Yossarian, or if not Yossarian then one of his buddies. Every single one. Eventually I just expected it whenever a woman appeared — Oh a girl? Cue the talk about her breasts. Oh someone’s fucking her (if not straight up raping her). Oh she’s gone.

Honestly if Heller had created even one human woman rather than propping up a series of breasts and vaginas, with a shrieking head somewhere in there, I might have forgiven this as typical men-writing-women and appreciated the good parts of the novel more. But he didn’t. And this book was published in 1961. Not Ancient Greece (where I expect women to be flowerpots and mere narrative devices)!

Additionally, this book is 450 pages (in my edition). It’s been said before, so I needn’t repeat it, but satire shouldn’t be this long-winded. For comparison, Juvenal’s Satires were usually a couple hundred lines of verse each. Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal is 48 pages. Animal Farm is 120 pages.

In conclusion: Am I glad I read it? Yea, but only because now I know that the critical praise doesn’t count for shit!! I stand by my assertion that there are no good American novelists. They don’t exist.

1 note

·

View note

Text

#this is the meme version of that intro to The Philoctetes#when Philoctetes is like ‘are you asking me to go to Troy for my benefit or for the benefit of the Atreidae?’#and it’s like ‘neither king 😔 it’s for the benefit of The Narrative’#the idea that characters must concede their very humanity to The Narrative is so brutal and horrifying and i’m in love with it#and OBVIOUSLY it can also be applied to Black Sails#Silver going through the whole story resisting The Narrative every step of the way but ultimately getting sucked into it entirely and#fully taking its side in the end#and being the one to enforce what the audience knows was inevitable from the start…#(Silver has some Aeneas energy going on but we don’t have time to unpack all of that rn)#but ANYWAY!!!!!!#yeah. i am Upset.#very much considered making the last box say ‘lol no’ but I ultimately decided against it 😂😂#hopefully the Energy still shines through

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantasy Racism™ Sure is Pretty White: A Critique of “Carnival Row”

One of the problems with the “politically relevant” fantasy genre is that it frequently offers “representation” and “relevant” critiques of social problems in ways which favor the representation of the oppressions people face, rather than of the people themselves--meaning metaphors which parallel fantasy races to people of color while using a predominantly white cast. Often times this further reifies the unmarked categories of the cultural context the work is produced in (ie whiteness as the dominant & default category), further marginalizes and dehumanizes people of color, and positions white folks as the victims of metaphorical white supremacy. Amazon’s new streaming original Carnival Row is an unfortunately clear example of this continued fetishization of white poverty/desperation/vulnerability at the expense of communities of color.

Spoilers below.

While one might rightly critique the “trauma porn” genre and the way that people of color are often brutalized on screen or depicted only as victims of violence in discussions of oppression, with the solidarity and resistance of communities of color erased from dominant narratives, substituting white bodies into these sequences of violence does not offer us a useful subversion. In her book What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, Elizabeth Catte talks about the historical and contemporary use of a particular image of white poverty. The focal example of Catte’s book is J.D. Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy (2016) where Vance consistently uses the image of the bad, dependent poor white to reify racist images of poverty and undermine the need for programs and systems to support poor folks--just one example of this is the way he insists that the “welfare queen” is real and implicitly argues that the use of this stereotype to undermine welfare programs is not racist because he has known white welfare queens. Outside of contemporary use, Catte also gives examples such as how in the 1960s “white poverty offered [white people uncomfortable with images of civil rights struggles] an escape--a window into a more recognizable world of suffering” (59), and the quotes Appalachian historian John Alexander Williams comments on the way that, in the displays of Appalachian poverty, “‘the nation took obvious relish in the white skins and blue eyes of the region’s hungry children’” (qtd Catte 82). This obsession with white poverty has little to do with addressing the actual problem; instead, it is a tool used to obscure oppression, resistance, and transformative solutions to these problems.

Carnival Row offers a discourse on colonialism, racism, and xenophobia intended to mirror the political climate of the real world, namely the violence experienced by refugees and undocumented immigrants. It also attempts to comment on the way that Global North/colonial nations often create or are implicit in the creation of catastrophes which cause Global South/colonized nations and regions to become unsafe and result in refugee migrations, as well as the subsequent way that many times when refugees end up immigrating to the very nations that played a role in the collapse of their homelands, they are met with violence on multiple levels and their traumas are ongoing. In this current moment, this kind of discourse/intervention is “relevant” (I use scare-quotes because while the treatment of refugees in many Global North nations is horrendous in this current moment, this is not a new problem the way it sometimes is imagined) and I’m even willing to concede that there are some things which I think are done well. However--and this is a big however--the choice to make a predominantly white non-human population the metaphorical stand in for real life people who are predominantly of color greatly undermines what the series is attempting to accomplish. The implicit message is that it is easier for general audiences to sympathize with and recognize the personhood in non-human white figures than it is to sympathize with and recognize the personhood in real life people of color who are actively experiencing the violence fictionalized in this series. Furthermore, even as the victims obscure the real role white supremacy plays in xenophobia and the violence experienced by migrants and refugees, it still is a form of trauma porn. The only real difference is that because of the dominant whiteness of the victims, this version of trauma porn allows for the voyeuristic participation in systems of violence wherein many who are passively complicit (or even actively responsible) in the very systems causing violence are able to relate to the victims and experience a sort of cathartic release which allows them to maintain their complicity, feeling “good” that they consumed “politically relevant” content which allowed them to “care” safely, without having to address the reality that they are part of the brutalizers not the brutalized.

One of the ways that the show attempts to somewhat skirt around this problematic of white victimhood is by giving many of the white refugees, namely the main character Vignette (played by British actor/model Cara Delevigne), Irish accents and setting it in a time period which ambiguously mirrors the time before (as Noel Ignatiev puts it) “the Irish became white”. Celtic whiteness is used both in Carnival Row and with the case of Appalachia, and seems to be a particular favorite flavor for the fetization of white poverty. My personal theory is that this is because, when used in this way, the British colonization of Celtic peoples works to simultaneously obscure the racialized realities of both poverty and colonialism--in this fashion, Celtic whiteness is Othered just enough to justify the creation of white victimhood as a fetish object, but still undeniably white enough to connect this victimhood to the universal construction of whiteness. While there is nothing inherently wrong with including Ireland (or Scotland or Wales) in discourses of colonialism/neocolonialism because Ireland and other Celtic lands were and are colonized by the British and this colonization has had a clear and lasting impact on these regions and these peoples, using it as part of the fetishization of white poverty does not further anti-colonial goals, and again is being used to displace and obscure the way racism and white supremacy are central to anti-refugee and anti-immigrant rhetoric, policies, and popular practices.

During the first few episodes, I tentatively imagined myself commenting on the only semi-positive aspect I saw in the show’s use of whiteness: while obscuring metaphors for white-supremacist politics are deployed in many fantasy works, they often position people (humans) of color as being members of the human-supremacist groups which are meant to reflect real life white supremacy, further obscuring the real stakes of the topic being discussed. For the first four episodes, Carnival Row avoids this problematic and gives a representation of the metaphorical anti-immigrant/“pro-Brexit” crowd exclusively through white humans--and bonus points, they can be found in both the political elite and the working class/poor. While the whiteness of fantasy races means that the real life targets of white supremacist violence (people of color) are obscured, at least this allows us to remain clear on who is responsible. That, unfortunately, changes in episode five. One of the major places where we can see this change is in the introduction of Sophie, a woman of color, who takes over her (white) father’s seat in parliament after his death. Sophie gives a speech where she mobilizes her status as a woman of color to further fantasy-racism, stating that her mother had “desert blood” and experienced racism, but that the city overcoming racism and recognizing the value of racial diversity does not apply to the “Critch” because “our differences are more than skin-deep” (ep 5, 34:15). While this is predominantly intended to differentiate real racism (which I guess has been solved?) from Fantasy Racism™, it also serves to undermine the dehumanizing politics of racism which are continuously deployed. It reassures audiences that real life racism can be solved because race is just skin deep and we’re ultimately all pretty similar. This obscures the historical and contemporary claims about “race science” and “racial difference” which often explicitly and implicitly justify racism. While in this present moment “race science” has become a more latent belief--most people laugh at the idea of measuring skulls--everyone with a White™ Facebook friend who's taken a 23-and-Me to prove they’re 0.005% African can speak to continuing beliefs in biological race theory.

Ultimately, like many other “politically relevant” fantasy works, Carnival Row’s use of a white washed Fantasy Racism™ as a metaphor for the systems of oppression that, in the real world, affect people of color remains highly problematic. In both our personal viewing practices and in our practices of creating and curating stories, we must think critically. Storytelling is a powerful tool in shaping how we perceive and consider reality, so when we choose to tell stories that represent marginalized communities exclusively by their oppressions, and especially when we choose metaphors that participate in the fetishization of white desperation and whitewash these communities we are doing real harm.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Belle Sauvage, by Philip Pullman

This book is quite something. When I finished it, it left me with a weird mixture of feeling amused and confused at the same time, and two days later I still can’t make sense of the experience that is reading this book entirely. In that respect it goes well with the original series, His Dark Materials, to which this new series (The Book of Dust) acts as a prequel. I was a lot younger when I last read His Dark Materials, so I’m not sure if this assessment still stands, but I remember this same feeling of being intrigued and confused at the same time, of not knowing exactly what to make of it all. Which doesn’t mean it’s bad at all, I quite liked His Dark Materials, and I really (mostly) liked this book, and I’m looking forward to the next installment.

First of all, I like the title. The book is named after a canoe that plays an important role in the story, and I know it’s an evil orientalist/racist stereotype, but it has such a beautiful ring to it, and weird as it sounds, I think it fits its bearer. It’s beautiful, it knows how to survive, it’s there to help when you need it... Yes I’m still talking about a canoe, for some reason I loved the boat and the protagonist Malcolm’s relationship to it most of all, and I was heartbroken when it finally sank.

Anyway, on to the less bizarre things I wanted to talk about. The pacing in the first half is relatively slow: there’s a murder mystery, and some generally odd things happening that don’t make much sense while you read them - and even after you’ve finished there are still many threads that haven’t been resolved (to my knowledge). There’s a strict distinction between the good and the bad guys (the bad guys is everyone who belongs to the church, the good guys is everyone else), but for both sides it’s not quite made clear why they act as they do, or what they’re even fighting over. These two aspects - black-and-white sides of a conflict, and rather superficially drawn characters - cause the impression that this is a children’s book that’s more concerned with the young heroes having adventures and fighting off the bad guys when the adults prove incapable of doing so. But honestly, please don’t read this to your children, there are some pretty brutal scenes, and the main antagonist is a disturbing, very much disturbed, paedophiliac rapist who for most of the story doesn’t seem to die, whatever you do to him. Those last two parts of his characterization are only alluded to more or less subtly, but at least for adult readers it’s unmistakeable, and even if a child misses it, he’s still a haunting presence throughout most of the book that you just can’t get rid of. Really, he’s scary, not because you see lots of gory action, but because he’s always there in the periphery of your vision, and because pretty much everyone, even the most capable characters, are terrified of him and have no idea how to stop him. When he finally dies, it’s almost a bit surprising because I wasn’t quite sure he was entirely human at that point. It felt a bit anticlimactic to me, like Voldemort just getting hit by his own curse and... dying, like everyone else. His dying rips that carefully cultivated veil of his omnipresence and omnipotence apart and shows that it’s not that important what he seems to be, but what he is underneath.

I feel like this is true for the story in general. From his writing it’s quite obvious that Philip Pullman is an adamant atheist who’s very critical of the church, and probably organized religion and religiosity in general. The church and its followers are constantly presented to be the bad guys, while everyone who commits themselves to science and learning is (mostly) good. I think his clear preference of science (as knowledge of the material world) over belief also shows in the imagery and the narrative of La Belle Sauvage. Despite being a work of fantasy that is set in a world of prophecies and witches, the book never concedes any greater meaning, any allusion to a higher being or a higher reason, just because there’s magic. It’s set at a time of scientific discoveries that has a decidedly rational atmosphere where there may not be an explanation for every natural phenomenom yet - but at some point there will be, so the simple fact of not understanding something yet doesn’t mean that there must be a transcendent, omniscient and immortal being to make sense of it all. I don’t remember the plot of The Amber Spyglass (His Dark Materials #3) all that well anymore, but I do remember that it features angels and the being that’s commonly called God, and it turns out to be rather inglorious.

La Belle Sauvage doesn’t go that far yet, at this point the greater narrative has only been alluded to, but there are a few supernatural elements in the story (to our eyes and also to Malcolm’s), and we see the same principle at work. There’s this one episode when Malcolm and his companions enter some kind of cave where the fairies live, and which is protected by a river deity. Malcolm and his friend Alice are clearly surprised that such a place exists, and they wonder a bit about how they ended up there, but they never question the reality of it all. What matters is their experiences with the place, the feel and smell of it, and the impact it has on their journey. By telling the story rather matter-of-factly and just assuming that there is an explanation for it, even though it’s not accessible to the protagonists, the supernatural element is stripped of its mystery, and therefore of much of the power it holds over people. Of course the fairy cave can’t go through such a mundane process as dying, like the antagonist does, but the same principle holds true: once you’ve gone through the whole thing, you’ve seen it in its entirety. You still might not understand everything about it, but the mystery is gone, and with it much if not all of its power. This demystification is poisonous to belief. I might be reaching here, resting claims on a narrow basis of evidence, but it seems to me that the message of this entire parallel universe, one where the church has never lost its political power and where the era of Enlightenment probably never happened, is that faith is a lie. Opium for the masses, if you like. Once people stop believing, it dies.

4 notes

·

View notes