#the idea that any artistic medium is an independent activity is an illusion

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

if i were an academic i would love to write a book about all the unseen human labor and lives that make it possible to produce a single quilt.

i don't use commissioned longarm services for my quilting because i can't afford it, but i also used to really struggle with the idea of having another person complete such a prominent part of my project. i thought i wouldn't be able to say 'i made this.'

but i didn't grow the cotton that got woven into the fabric i'm using.

i didn't design the printed fabric collection.

or paint the batik.

i didn't do the math and writing that went into the patterns i use.

i didn't drive any of the ships and trucks that transported the fabric.

i didn't mine the metal that turned into the needles in my machine or hand.

i wasn't the shelf stocker at the chain store or the owner of the indie shop i bought from.

quilting is an inherently collaborative art form. the creativity didn't start with me.

#the idea that any artistic medium is an independent activity is an illusion#a thick 350-page book with color photos in the middle#OR a solid 90 minute documentary#quilting#crafting#sewing#(the idea that any human activity is an independent event is an illusion)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

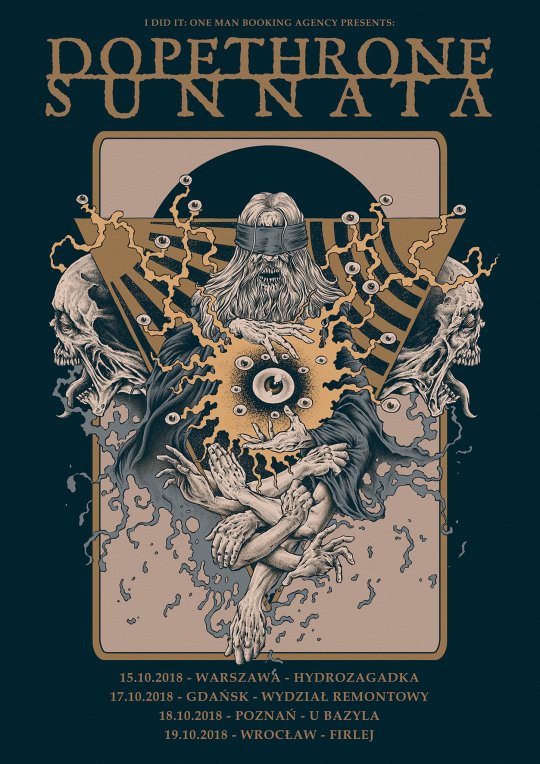

Tripping Through the Void with SUNNATA

It's been four years since Doomed & Stoned visited SUNNATA and my how they've grown in the interim! Three successful independent releases, legendary live performances, an exponentially growing fanbase, and broad critical acclaim have shifted the spotlight on the Warsaw doomers. Long before they became the juggernaut of the heavy underground, we knew them as an exciting upstart called Satellite Beaver. This week, we give Sunnata’s latest collections of songs a thorough going over and speak with Szymon Ewertowski (guitar, vox), Adrian Gadomski (guitar), Michał Dobrzański (bass), and Robert Ruszczyk (drums) about what fuels their fire.

Heart of Storm

By Simon Howard

Polish loners Sunnata offer the melodic pilgrim a ritualistic, dark, heavy journey into the atmospheric Outlands, hypnotizing us with an eternal 48 minutes of tripping. Pineal glands will decalcify, doors of perception will be cleansed, and the listener will be enlightened.

Sunnata have been creating a musical Zenith in a blend of genres since 'Climbing the Colossus' (2014) and 'Zorya' (2016). This well-crafted album is hard to believe, in the fact that this band have only been around since 2014. Incorrect. Jump in the TARDIS of Tunes, and rewind ourselves back to 2008. Under the moniker of Satellite Beaver, they released two demos and one final EP in 2012, aptly named, The Last Bow. If the reader is not familiar with Satellite Beaver, then you have an amazing musical journey ahead of you.

Outlands by SUNNATA

'Outlands' (2018) was recorded at Monochrom Studio, mixed and mastered by Haldor Grunberg of Satanic Audio, and brilliantly saturated in the artwork by Maciej Kamuda.

I really cannot attest to what was in the Kool-Aid at Monochrom Studio, but the results are spiritually absorbed into the listener's soul. Mind expanding mantras like "Lucid Dream," "The Ascender," and the epically entrancing closing track "Hollow Kingdom" appeal to me on planes we can only experience ourselves. Outlands transitions from mellow meditational hymns to heavenly heavy riffs, blending this album into something transcendental for avid or new fans of Sunnata. This journey will be taken upon by many, and many times. Musical Mecca has been found. The void has been filled.

Soon It Will All Be Gone

A Conversation with Sunnata

Interview by Billy Goate | Photos by Justyna Kamińska

How would you characterize the evolution of sunnata from ‘Climbing the Colossus’ to ‘Zorya’ to your latest record, ‘Outlands’?

It’s been a long way. I would describe it as emotional trip from anger on our debut Climbing the Colossus, through spatial epicness and a need for air on Zorya to introverted melancholia you can dive into on Outlands. In general, we have always been the "sad guys" who were into kind of a gloomy, dark state of mind and soul and our approach towards the music evolved along with our skills of using instruments to express what we feel inside. That’s why I’d characterize our evolution as a path to greater complexity of emotions, where our debut was the simplest and our latest album the most complicated, emotion-wise.

Are there thematic motifs that the band finds attractive when writing songs? Which themes were most influential on 'Outlands’?

We definitely have become more lyrically confident since our previous album and even though we still consider the role of our lyrics as backing for the rest, I think we can finally admit that Sunnata actually has something to say! (laughs) It might not be your most positive answer ever, but our motifs on Outlands consist of loneliness, despair, the negative influence of religious fanaticism, helplessness, and development of the self and whatever conflict you have inside of you. We dig deep, reopen wounds, and push to get to the core. We prefer fighting yourself to fighting others, until you turn into none.

Are the songs on the new album connected in any way? Is this all a “Lucid Dream” that culminates in a journey into the “Outlands,” with “The Ascender” climbing some forbidden mountain of the gods? And what is the “Gordian Knot” -- an internal fight-or-flight struggle? At the end of the journey, is the prize the conquest of a “Hollow Kingdom”? So many questions!

Sure! Song order always comes last, so we have no intention in putting a story together in any way. However, this sort of lyrical consistency allows us to arrange one after another in a way that triggers certain emotions and impressions. Let’s get through the album piece by piece:

"Lucid Dream" encourages you to give, not to receive; to understand that if you separate your self-esteem from the external world and build value of self and the will to explore, you will grow as a human.

"Scars" is a story of being misled, lied to, cheated on, and abandoned on the one hand, but also a story of growing strength and power to end whatever harms you.

"Outlands" was actually inspired by some politically related events. It's all about sacrifice as a way to bring attention to an idea or social problem ignored before. Too deep to dig into it in a single interview.

"The Ascender" track is focused around any sort of radicalism giving an illusion of being permitted to force your point of view on others. We disagree with anyone’s feeling to be justified for actions that do harm. It’s an illusion that keeps you away from self.

"Gordian Knot" is exactly what you have interpreted: inner struggle -- one that can make you fall apart or disintegrate, in any way.

"Hollow Kingdom" has been chosen as climax, the ending song in praise of emptiness. Its structure, repetitive feeling, and overwhelming melancholia are the best ending of an album we could choose from this track list.

Tell us about the artwork, the artist you chose, and the layers of meaning behind this many-faced wraith?

The only constant is change to us. That’s why this time, instead of going with the magnificent Jeffrey Smith of Ascending Storm once again, we decided to go with another talented artist, Maciej Kamuda, who is also author of Weedpecker and Major Kong artwork. We felt a strong urge to do something different. Deity presented on the front cover is a variation on deep symbolism of Goddess Kali. We didn’t want her to look in a way she’s known from Hinduism. We were inspired more by deep, complex symbolism behind her various forms. If you read about her, you will instantly get it.

One consistent word that comes up in all the descriptions of your music -- live performances especially -- is “ritualistic.” Whether it is the careful setting of the stage, the lighting of the incense, or the hypnotic, trance-like rhythms of the music. What is the importance of ritual for the band and what does this bring to your compositions and performances.

Ritualism in our music comes from trance-inducing forms we create. Immersed in void and drugged with noise, we jam a lot in search of the desired emotion trigger -- we can’t name it, we just get the feeling. If we do, we proceed further. Our work routine and who we are as people actually doesn’t have much to do with dark shamanism, but everything changes once we take instruments and start playing together. It’s similar to being possessed with something. All other details you mentioned -- stage setting, light, clothes, and merch -- are secondary to this and their role is to create certain atmosphere to take people on the journey with us.

I've heard rumors of a music video in the works?

Videos are our curse. We’ve been working on them for every album, but for various reasons all these projects were abandoned. Right now, we are at the beginning of production process for video of "The Ascender" song and we really do hope that it will work out this time. I can’t tell much yet, but we would like the outcome to be something similar to our music -- '90s aesthetics in a psychedelic, doomy setting. We’ll see what time will tell.

Let’s close by giving our readers a peek at your touring plans for 2018 and beyond. What “Outlands” are you off to in the days and months ahead?

We can’t reveal many dates since they are not officially announced yet, but after the our spring tour of Scandinavia with the crazy lads of Boss Keloid, we have various festivals in the summertime confirmed and good perspectives on touring Europe with Dopethrone in October, plus an appearance at Gizzardfest in Rotherham, UK. I believe that best is yet about to come. We just need to follow our own path.

Ruling Land of Emptiness

By Shawn Gibson & Billy Goate

To understand the significance of Sunnata's musical achievements, we need at least a cursory understanding of the soil in which the band is planted. Poland's heavy music scene has been experiencing a surge of activity over the past decade or two, but its music roots are deep-seated and stretch back generations to the darkly complex oeuvre of composers like Frederic Chopin, Leopold Godowsky, Karol Szymanowski, Henryk Górecki, and so many others.

Sunnata's home base of Warsaw encompasses an impressive if turbulent history, evolving from a smattering of villages more than 1400 years ago to become one of the ten largest capital cities in Europe. Warsaw has had more than its share of doom to contend with, too, from disease and famine to regional and global wars -- including the devastating Nazi occupation, which spurred the great underground resistance movement known as the Warsaw Uprising.

Given this context, it's significant that Sunnata has adopted a name representing one of the fundamental principles of Buddhism. Śūnyatā is a transliteration of the Sanskrit word शून्यता (pronounced as "shoonyataa"), which signifies voidness. Think of it as a meditative state of "emptiness" in which the mind is devoid of desire, specifically the stubborn presence of that word we all learn by age two: mine. Śūnyatā involves the diminishing of one's ego, and the band that wears this name has dedicated the better part of a decade to exploring this philosophy through the medium of ritual heavy music.

Photo by Aleksandra Burska

"Hollow Kingdom," the closing track on Outlands, is one example of Sunnata's approach to voidness, with its droning ups and downs and subtle twists. Sunnata let this song be the pedals of a cherry blossom drifting in the breeze. Another highlight is "The Ascender" (my favorite of the record). It's the kind of vessel one imagines boarding to cross over to निर्वाण (nirvana). The backing vocals near the beginning of the song calls to mind prayers and mantras of Tibetan monks. Guitars buzz like propellers, shuttling you along to another plane of existence. The heavy psychedelic vibe and stirring chorus makes for an uplifting experience that is, one imagines, not unlike astral projection. Sunnata are your gurus fixed atop the mountain, lulling you ever closer on an ascendant journey skyward. Along the way, there's an avalanche of emotions.

One imagines the many plagues, fires, wars, and uprisings that might have influenced "Scars." The song strikes a thrash-like tempo, with jazzy cymbals and a psyched-out tambourine. Then, at the five-minute mark, all hell breaks loose with a thundering bassline, fuzzed-out guitars, and a pummeling drumbeat. Doom has come to claim its reign! Similarly, "Gordian Knot" attacks like a nest of pissed-off hornets. Still rocking hard by the two-minute mark, things lighten up for a spell as fuzzy desert riffs and reassuring chants (with those wonderful backing vocals) lull you to sanctuary. The aggressive pace returns, leading to a crescendo of screaming vox to chase every worry from your mind. Only the journey consumes you now.

youtube

Taken in sum, Outlands is an exhilarating magic carpet ride, albeit with some turbulence. Sunnata hone the powerful elements of rock and metal like master alchemists, dispensing measured doses of doom, sludge, psychedelic, and stoner, melding them seamlessly, and transcending boundaries only few conceived possible. The heavy doom passages are somehow made even heavier by this psychedelic blend, which brings one closer to a state of voidness.

High spiritual concept meets the earthy might of doom in Outlands. It is the enlightenment of the yogis, the ascension of gurus, a musical Kathmandu. I've visited the temple now multiple times over the course of weeks and months and it continues to be a cathartic experience for me. Outlands will make your heart flutter and embolden your spirit with its mesmerizing riffs and hypnotic rhythms. It will usher you down a river of feeling and bury you in a cascade of sonic desolation. The chants and mantras sent my spirit soaring heavenward. Returning to earth, I felt as if I have been everyplace in existence and at the same time perfectly still, third eye open -- mind, body, and spirit aligned. Awareness is the gift I received from this Outlands. Who knows? In listening, perhaps you will find your own Śūnyatā, as well.

Follow The Band

Get Their Music

#D&S Reviews#D&S Interviews#sunnata#Warsaw#Poland#doom#sludge#metal#doom metal#Svempa Alveving#photography#Justyna Kamińska#Simon Howard#Shawn Gibson#Doomed & Stoned

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Serious Play: An Interview with Sam Cornish

Installation view of “Kaleidoscope: Color and Sequence in 1960s British Art” (2017), Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park (© artists and estates. Photo by Jonty Wilde)

As a period in postwar art the Sixties has perhaps been subject to more scrutiny than any other. But what is the purpose of such activity? To reinforce existing narratives, or to produce new ones? In Britain, specifically, there has been a tendency to link artistic production to a festive attitude that marked the decade as a whole, melding it with a broader cultural image of “Swinging London.” Kaleidoscope: Color and Sequence in 1960s British Abstract Art draws on works held in the Art Council Collection to make a focused appraisal of such assumptions. The exhibition presents the viewer with artworks that are very much at play, and yet it points to the integral role symmetry and repetition played as underlying principles. Sam Cornish, one of its organisers, is an independent curator based in London. In addition to having recently produced a number of projects analyzing art made during the 1960s and 1970s, he also edited the online journal abstractcritical.com.

* * *

Neil Clements: I wanted to begin by asking about the curatorial premise of the exhibition. There is a real sense that both repeated sequences and a sustained interrogation of color were central to the practices of each of the artists you’ve included. The question I found myself mulling over was precisely how color and sequence interact with one another. Does color interrupt sequence, or reinforce it? Or both?

Sam Cornish: When the Arts Council asked me to put together a proposal, they had a very open brief. I first thought of the idea of sequence and symmetry because I’d noticed that they featured in the so-called “New Generation” sculpture of artists such as Phillip King, Tim Scott, Michael Bolus, William Tucker and David Annesley. I then quickly realised that these attributes were also present in very different ways in Pop and Constructionism [the name sometimes given to post-war British Constructivism]. As well as enabling us to pose the art historical questions of what sequence or symmetry meant to these different artists, sequence and symmetry appealed to me because it is very directly communicated. Even without any knowledge of the period, I think a reasonably attentive, sensitive viewer could understand that the works are linked in this way.

William Tucker, “Thebes” (1966), Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London (© the artist)

Color was, for me at least, of secondary importance. It is difficult to avoid in the art — at least in that of younger artists — produced in Britain at this time. If you’re going to include the ’60s sculpture of King, Scott, Bolus, Tucker, Annesley or the paintings of John Hoyland or Jeremy Moon, you are going to get color — and a very typical color at that: bright, saturated, more artificial than it is naturalistic.

NC: Given that so many of the artworks take the form of painted sculpture, or shaped canvases, I was wondering if you could say something about the way in which artists at the time saw distinctions between disciplines like painting and sculpture as operating?

SC: Natalie Rudd, who I curated the exhibition with, quotes the very active Whitechapel Gallery curator Bryan Robertson in her introduction to the exhibition: “For a long while painting, in many ways, has tried to approximate to the condition of sculpture, which, in turn, has pushed increasingly towards the special plasticity, fluidity and freedom of painting.” It’s interesting that modernism is often described solely in terms of medium specificity, when in actual fact there was quite a lot of interaction, sometimes involving the subsuming of one in the other, elsewhere leading to hybrid forms. Certainly a significant tranche of painting became flatter, threw out 3-D illusionistic effects etc., and it would be very misguided to ignore the importance artists placed upon advancing the categories of “Painting” and “Sculpture.” But sculpture in a huge variety of ways looked to painting to lead the way — as Robertson realized, the use of color was only the most obvious. Even very flat Color Field painting, by denying recessive illusion, can emphasize its status as a physical presence in the room, and so resembles, in effect, a flattened sculpture.

Installation view of “Kaleidoscope: Color and Sequence in 1960s British Art” (2017), Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park (© artists and estates. Photo by Jonty Wilde)

NC: A lot of scholarship on 1960s British art focuses on its relation to work being made in the United States. This is particularly the case with abstraction. How much do you think the work in the show represents either the influence of American art, or operates as a deliberate refutation of its values?

SC: It is undeniable that many British artists looked to American art at this time: the Color-Field Painting of Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski and Morris Louis was a decisive influence on much of the work in this exhibition. I am a little wary, though, of posing the question of British versus American art. For example, if you look at something like the exhibition catalogue of American Sculpture of the Sixties, which was held at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1967, there was a huge diversity of work being produced. American art was not a monolithic category. It’s also notable that Caro was included in that exhibition as an honorary American. For a time the influence of Caro can be seen in a number of American sculptors, like Willard Boepple or James Wolfe.

John Hoyland, “15.5.64” (1964)

, The John Hoyland Estate (courtesy the Estate of John Hoyland)

John Hoyland, whose catalogue raisonné I am currently working on, is an interesting case, too. The example of American art was hugely important to him, but their example was tempered by his interest in the more complex, illusionistic, and less expansive art of earlier European modernists, such as Nicolas de Staël. Part of the distinction of Hoyland’s art from that of painters such as Noland and Olitski is the sense of weight and physical presence he imparts to the areas of color in his paintings. This is very noticeable in “15.5.64,” which is shown in Kaleidoscope, and can be directly traced to British sculpture by Tucker or Caro.

It is also worth distinguishing New Generation abstract sculpture from American Minimalism, particularly as there seems [to be] a growing trend to label all reductive art “minimal.” One way to do this is to look at their differing use of Brancusi: American sculptors seemed to have emphasized the exterior, space-occupying aspects of his art, as they moved toward the environmental and the literal, whereas British sculptors emphasized the illusionistic aspects, the rhythms within Brancusi’s structures, as well as his mystical or symbolic side. This is a generalization, but perhaps a useful one.

NC: As well as a number of artists no doubt familiar to many, figures like Anthony Caro, Bridget Riley or Joe Tilson, there are a number of artists whose work people visiting the exhibition might be less familiar with. When you were selecting the show did you want to expand upon what we choose to remember about the period?

SC: Yes, certainly. One of the artists in the exhibition wrote to me yesterday saying they thought it “the first time that period is being properly looked at.” I’m not sure that is entirely the case, but it is true that the abstract art of this period has been neglected, beyond the isolated examples of figures such as Caro and Riley. In particular, we really need to have a large survey exhibition looking at “New Generation” abstract sculpture — there hasn’t been one since Alistair McAlpine’s collection was gifted to the Tate Gallery in 1971! As well as this large survey many artists deserve proper retrospectives — I think Tim Scott and Richard Smith spring to mind.

Installation view of “Kaleidoscope: Color and Sequence in 1960s British Art” (2017), Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park (© artists and estates. Photo by Jonty Wilde)

NC: A number of the artworks have been restored prior to the exhibition. I think this presents an interesting issue, because these artworks were initially celebrated for the sense of newness they radiated. But just how fresh should something that’s half a century old-plus look?

SC: You’re right that newness is part of the aesthetic effect of much of the art in the exhibition. I suppose there are different types of newness. Regardless of condition, a sense of newness is going to differ substantially when an object is fresh out of the studio to when it is re-displayed six decades later. The newness of Pop art will likely tend to an ability to read cultural clues. Newness is a part of abstract art (beyond the ’60s) perhaps because it is so often tied up with attempts to create an entirely unknown — and therefore “new” — thing.

The difficulty of storing and keeping pristine large painted steel and fibreglass sculptures is very likely one aspect behind the neglect of this work. However, I confess that I’m not very interested in the “conceptual” debates that are generated around restoration: if a work can be restored to its original condition then great, if not, that is also potentially okay.

Kaleidoscope: Color and Sequence in 1960s British Abstract Art continues at Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park (West Bretton, Wakefield, United Kingdom) through June 18.

The exhibition will travel to Nottingham Lakeside Arts at the University of Nottingham, Warwick Arts Centre at the University of Warwick, and the Walker Art Gallery at the National Museums Liverpool.

The post Serious Play: An Interview with Sam Cornish appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2sBfJbH via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Interview: Joe Banks + Disinformation

Joe Banks is a sound artist, author and researcher, originally specialising in radio phenomena and electromagnetic noise. For over twenty years Joe has been performing, releasing albums and exhibiting under the guise of Disinformation. This Disinformation brand name allows for a critique of corporate identities and modern communication, and uses a sonic palette sourced from errant radio waves, natural earth signals, and interference from the sun and from the National Grid, etc. In 2012, Joe published “Rorschach Audio – Art and Illusion for Sound” on Strange Attractor press, a book that explored the subject of EVP (ghost voice) research in contemporary sound art practice. Joe’s work currently focusses on language and evolutionary neuroscience. Joe lives in London, 40 metres from the spot where physicist Leo Szilard conceived the theory of the thermonuclear chain reaction.

For more information, please visit https://rorschachaudio.com/about/ All images courtesy of the artist.

………………

Ilia Rogatchevski: Disinformation began in the mid-1990s. What was the conceptual reasoning behind branding your creative output, rather than just making works under your given name? Has the conceptual framework behind the Disinformation handle changed or shifted in the last twenty years?

Joe Banks: To clarify when it was that all this activity started, the first Disinformation solo releases were published by the record company Ash International – an imprint of Touch Records – in 1996. The first collaborative recording, where I contributed Very Low Frequency (VLF) radio noise, to a track by Andrew Lagowski’s SETI project, appeared on a compilation CD called “Mesmer Variations” in 1995, and that contribution is credited to Disinformation in the printed CD sleeve-notes.

The name Disinformation works well for performing concerts and publishing LP and CD tracks, but was intended as much as a brand name. At the time I was interested in exploring ideas around corporate communications, logo design, corporate identities and branding. The name Disinformation also suggests parallels with philosophical concepts like the Liar Paradox and so-called Strange Loop. The name is also useful in collaborating with other artists. Creating collaborative artworks and publishing under the authorship of “Joe Banks” could arguably be misleading for audiences and disrespectful to collaborating artists.

If I’m writing research, obviously I have to publish using my own name. However, I’m also careful to not just acknowledge, but to actively advertise all the inspirations and sources that I make use of, in terms of the artists who’ve inspired my artworks, and the authors of material used in research work like the “Rorschach Audio” project.

As for the name itself, with all this talk of “post truth” politics, “fake news”, and Michael Fallon’s recent statement about “weaponising misinformation”, if anything, the idea of encouraging scepticism is more prescient now than it has been at any point in the last twenty years.

youtube

IR: What attracted you to using sound as a medium? I’m particularly interested in finding out what your gateway to experimenting with radio waves (VLF, ELF, Noise from the sun and and the National Grid) was. What creative potential do you see in radio?

JB: Part of the appeal of making sonic art using VLF radio noise was that on the one hand the imagery associated with VLF is just extraordinary – electric and magnetic storms, radio science, electricity, space physics, communications science, defence electronics, etc. On the other hand the techniques required to record these phenomena are technically straightforward and cheap to realise. It was really about research, about ideas, and a creative thought-process, rather than being about technology as such.

IR: In the past you’ve described your work as being akin to natural wildlife recording. Do you find that recording storms or interference places you in a similar realm of debate as soundscape studies and acoustic ecology? Do you see interference, i.e. your source material, to be a pollutant on our (sonic) landscape?

JB: The idea of presenting recordings of electromagnetic interference as a form of wildlife recording is important, but only really applies to a few Disinformation tracks – unprocessed, un-remixed field recordings like “Theophany” (meaning “The Voice of God”), “Stargate” [both from the “Stargate” LP, 1996] and “Ghost Shells” [12”, 1996] for instance, and, later on the “London Underground” and “Bexleyheath to Dartford” tracks [from “Sense Data & Perception”, 2005], but the idea’s still relevant.

Compared to the acoustic ecology movement, part of the artistic strategy was to poke fun at some of these over-romanticised conventions about what’s considered “natural”. The idea that any electrical activity, and, even more so, any human activity, is or can be part of nature goes against the more sentimental notions that some people project onto what they see as being nature.

In contrast, it’s about stressing how electricity is an aspect of the natural world, as opposed to being exclusively and purely a product of technology, and about stressing how human activity is part of nature – stressing these facts as a positive, as an expression of idealism, to question traditional ideas about how we’re seen as distinct from other species and from the rest of the natural world.

youtube

IR: Reading through some of the materials you sent me, I’ve noticed that you place great emphasis on copyrighting your work, images, sounds and ideas. While this is not uncommon, I’m interested to find out what your relationship is to appropriation, synchronicity and originality in art? In the example of Tacita Dean’s ‘Sound Mirrors’, is it possible that there was overlap in interests, rather than outright theft of intellectual property? Have there been other examples where your work has been subjected to misuse or appropriation without your consent?

JB: It seems pretty obvious that from time to time artists do independently re-discover aspects of each others’ ideas, in good faith, so-to-speak. It seems equally obvious that problems with genuine rip-offs have as much to do with issues of professional and personal courtesy and common sense as they have to do with actual copyright law, but, to be honest, I don’t think there is any more emphasis on copyright in my work than you’d find in any mainstream cultural product.

It’s more a question of not being naive about the fact that today’s avant-garde cultural experiments become tomorrow’s mainstream and trying to protect yourself from exploitation in that context. Copyright is far too complex a subject to do justice to here, but I notice that in your own material you talk about being influenced by the Situationist writer Guy Debord, who is perceived as a famous, almost legendary, opponent of copyright.

What is less well-known is that Guy Debord, his partner Alice Becker-Ho and Debord’s friend, Gianfranco Sanguinetti, all asserted and defended their own copyrights when they felt their ideas were being misused (and this is well documented on a pro-Situ website called “Not Bored“).

As a case in point, from 1999 to 2006 my research project “Rorschach Audio” generated between £0 and £150 per year, mostly in lecture fees. Then, after successfully fending-off a number of fairly blatant copyists, from 2007 to 2012 the project attracted £234,000 in AHRC funding. Suffice to say that I only got to see a small portion of that funding in terms of personal salary, but this does show how much ideas can go on to become worth, even, in some cases, after years of being marginalised and ignored.

IR: I’ve been reading “Rorschach Audio” with great interest and while I consider the subject of EVP to be a bit of a red herring, I wonder if you’ve come to a consensus regarding the reason why artists are attracted to and get sucked into working with EVP? Is there anything beyond the grief/loss factor or the lo-fi aesthetic?

JB: The Electronic Voice Phenomena – ghost voice – belief system is just so blatantly false that when I first got involved with sonic art my attitude to EVP was outright hostile. I didn’t become interested in EVP until it became apparent that the psychological processes which enable people to mishear poor-quality voice recordings as ghosts, are, in themselves, more interesting than the recordings themselves. But it never ceases to amaze me how many people in electronic music, alternative and mainstream art, even academia, seem sympathetic to the idea that EVP recordings are actual ghosts.

One reason, perhaps, that a few people get attracted to EVP, is, frankly but honestly, because they flunked science at school, so they don’t seem to understand why it is that using a bit of made-up technical jargon and messing around with electronic recording technology isn’t enough to make EVP experiments “scientific”.

From time to time, and particularly among some artists, you also come up against a kind of postmodernism-by-numbers, which is so anti-rational that some people don’t seem to understand what science is, why science is important, or how science works; who have little concept of the distinction between science and technology, and no concept of science being a methodology first and foremost.

Obviously bereavement can be a genuine motive, but in some cases artists choose to work with EVP because it seems to challenge conventional thinking, albeit on a very superficial level. And because EVP recordings are just really easy to make.

IR: How has your research developed since the publication of “Rorschach Audio” in 2012? I get a sense that you’re moving into a more language-focused direction. Is the technology that’s responsible for most electronic music now playing a smaller part in your practice?

JB: I should stress that I’m actively continuing to exhibit and to develop all the existing work; also, since 2012, a great deal of new material has been published on the “Rorschach Audio” website. “Rorschach Audio” features have been published in places as diverse as the lifestyle magazine of the Soho House hotel chain and “The Psychologist” – the magazine of the British Psychological Society.

Having said that, you’re absolutely spot-on – whereas in the early days “Rorschach Audio” focussed on illusions of sound, as the project progressed, the focus shifted towards illusions of language, then to language more generally. Technology itself has never really been the prime focus – as the “Rorschach Audio” book says, “the earliest form of sound recording technology was not a machine but was written language”.

Even when I was producing sound art almost exclusively with VLF radios, even that work was really about radio as a sensory extension. It was about psychology of perception, and this is something that makes this work qualitatively different from most work by artists who’ve used electromagnetic noise. It’s what Geoffrey Grigson called “the electricity of the mind”… it’s about excitement… it’s about ideas.

In light of what you say, if I may I’d also encourage your readers to check out an article I wrote about evolutionary neuroscience, with the subtitle “visual reality is in itself a carefully constructed optical illusion”, for the website of the AXNS [Art X Neuroscience] Collective (see below). That is one I’m particularly proud of, not least because it’s almost exclusively about visual perception, and, in fact, because it says almost nothing about sound at all.

AXNS Article Part 1 | AXNS Article Part 2

Ilia Rogatchevski Originally conducted for Resonance 104.4fm in November 2016 Published by Ear Room, 4 March 2017

0 notes