#the human condition and memory and symbolic accretion

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fruits of my labor.

The US is complicit in the genocide in Palestine. Shoe memorials are often constructed to represent those who have been killed in genocide, leaving behind a loud absence. Shoes are often considered "desire objects" in that they are finite , personal belongings that make that absence more apparent. This is a tiny shoe memorial but I will be presenting it proudly and loudly in class for my final tomorrow.

Guess I'll make a bunch of tiny shoes out of clay 😐

#shoe memorials have become very important to me#look up shoes on the danube#and then shoe memorial gaza#weep with me#wish everyone in the world could hold my hand and take public culture class with me#we are dissecting meaning in here#the human condition and memory and symbolic accretion#auuuuuuu#< what working on a project for more than 12 hours basically straight through will do to you

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

a very long post about hozier - unreal earth

Index:

Lyrical allusions

Visual imagery

Reading list

Interviews

Reviews

Lyrical allusions

The lyrics on Unreal Unearth are informed by texts such as Irish writer Flann O’Brien’s philosophical 1967 novel, The Third Policeman, Dante's Inferno, and Jonathon Swift.

De Selby (Part 1)

At last, when all of the world is asleep You take in the blackness of air The likes of a darkness so deep That God at the start couldn’t bear

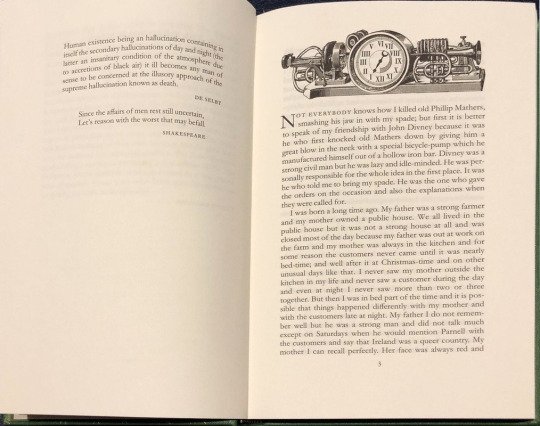

"Human existence being an hallucination containing in itself the secondary hallucinations of day and night (the latter an insanitary condition of the atmosphere due to accretions of black air) it ill becomes any man of sense to be concerned at the illusory approach of the supreme hallucination known as death." The Third Policeman - Flann O'Brien

Bhfuilis soranna sorcha Ach tagais 'nós na hoíche Trína chéile; le chéile Bhfuilis soranna sorcha Claochlaithe is claochlú an ealaín Is ealaín dubh í Bhfuilis soranna sorcha Ach tagais 'nós na hoíche Trína chéilе; le chéile Bhfuilis soranna sorcha Claochlaithe is claochlú an еalaín Is ealaín dubh í

Although your bright and light […] You arrived to me like nightfall, you come like nightfall You and I sort of mixed together You and I metamorphosized So that same idea of you can’t see where one begins and where one ends that, that is some kind of metamorphosis of some kind

“a body with another body inside it in turn, thousands of such bodies within each other like the skins of an onion, receding to some unimaginable ultimum”

De Selby (Part 2)

What you're given, what you live in Darlin', it finds a way to live in you

"The gross and net result of it is that people who spent most of their natural lives riding iron bicycles over the rocky roadsteads of this parish get their personalities mixed up with the personalities of their bicycle as a result of the interchanging of the atoms of each of them and you would be surprised at the number of people in these parts who are nearly half people and half bicycles"

First Time

Remember once I told you about How before I heard it from your mouth My name would always hit my ears as such an awful sound

First Time refers to Beatrice Smiles: Canto XXXI - Dante's meeting with Beatrice after being left by Virgil, where she rebukes him for his sins. Dante does not remember his name but recognises Beatrice. He was dunked into the River of Forgetting by Matelda

“Respond, you of poor memory, confess. _Lethe awaits. Your thoughts are undeterred.”

These days I think I owe my life To flowers that were left here by my mother Ain't that like them, giftin' life to you again

Francesca

In Dante's Inferno, the character of Beatrice embodies love inspired by God - she is a religious object that should inspire faith, devotion, and salvation. By contrast, the character of Francesca da Rimini is encountered in the Terrace of Lust. She was a medieval noblewoman who was killed by her husband, Giovanni Malatesta upon discovering an affair between her and Paolo Malatesta (his brother). She represents love that leads one's soul to destruction.

I would not change it each time Heaven is not fit to house a love like you and I I would not change it each time

"Love led us to one death, conjointly felled. __For him who slew us, Cäina waits below."

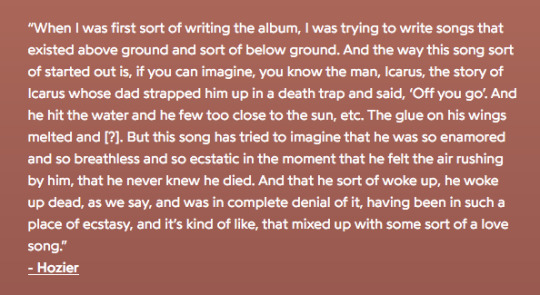

I Carrion (Icarian)

One deep breath out from the sky I've reached a rarer height now that I can confirm All our weight is just a burden offered to us by the world

This song has a connection with Inferno 17. Phaeton, Icarus, Daedalus and Arachne: are symbolic of Ulysses, the embodiment of transgression in Dante’s personal mythography. Icarus is a figure of fear for because he was equipped by his father to alter the boundaries of man's physical nature. It is the sin of pride that leads one to folly.

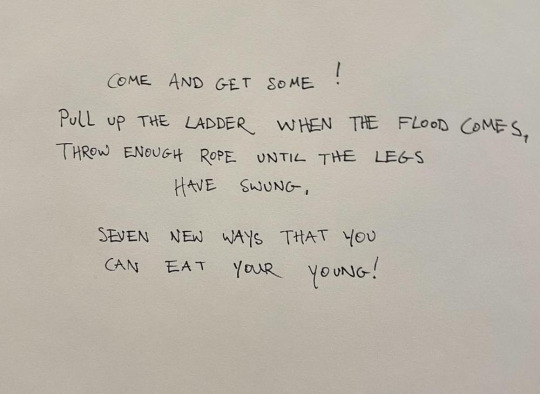

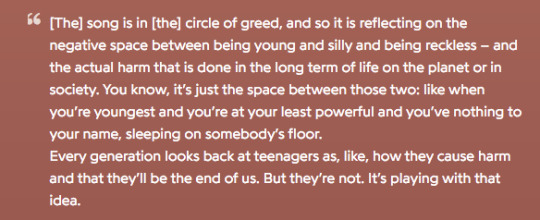

Eat Your Young

“Eat Your Young”, a contemporary riff on the Irish writer Jonathan Swift’s 1729 satirical essay “A Modest Proposal” that suggests Irish people eat their children to alleviate their hunger and poverty.

Come and get some Skinnin' the children for a war drum Puttin' food on the table sellin' bombs and guns It's quicker and easier to eat your young

The first verse also contains allusions to Canto 6 of Inferno - this level is related to "gluttony" but it's used by Dante to discuss the political landscape and moral failures of the City of Florence. Gluttony, in this case, is defined as excessive desire for dominion and power. So Hozier comments on inequality and poverty with a distinctly political air.

Damage Gets Done

Here Hozier refers to Canto 7 of Inferno and the concept of misura - a lack of moderation or self-control

And darlin', I haven't felt it since then I don't know how the feelin' ended But I know being reckless and young Is not how the damage gets done

In this Canto, Dante is discussing wealth management - hoarding and wasteful spending. While avarice is a traditionally Christian sin, Dante inserts the sin of prodigality by himself. This tells us that Dante's moral standard is not essentially Christian. Hozier also plays with the intentions of the texts he refers to and inserts his own takes on philosophy and biography. Very Dantean, if you ask me.

Who We Are

I think this is a narrative shift similar to Canto 8-9 where the fallibility of Virgil is explored and the tension between faith and fear.

You only feel it when it's lost Gettin' through still has a cost Quietly, it slips through your fingers, love Falling from you drop by drop What I had left here I just held it tight So someone with your eyes might come in time To hold me like water Or Christ, hold me like a knife

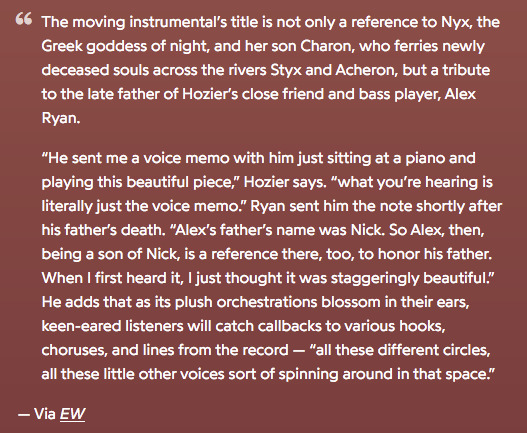

Son of Nyx

All Things End

The mystery at the heart of Inferno 10, the mystery that generates its enormous poetic power, is the connection of love to sin.

All Things End is superficially about the end of a relationship but it's also about heresy. The specific heresy in the canto is Epicureanism: materialism that suggests the soul dies with the body. It is a denial of the idea of an immortal soul and a "wilful separation of the soul from God". The Epicureans in Canto 10 are represented as eternally trapped in the temporary and ephemeral materialistic reality of the present. They are denied what is eternal and transcendent (ie divine)

And all things end All that we intend is scrawled in sand And slips right through our hands And just knowing That everything will end Should not change our plans When wе begin again

To Someone From A Warm Climate (Uiscefhuarithe)

‘Uiscefhuarithe’, as described by Hozier, is an irish word for ‘something that has been made cold by water’.

Butchered Tongue

The Genius annotation gives a lot of detail here: In “Butchered Tongue”, Hozier tackles the 7th Circle of Hell Canto XII to XVII, known as the ‘Circle of Violence or Hell of the Violent and Bestial’ which is one of the lower circles of Hell and is divided into three distinct rings, each punishing different types of violence. The track focuses mainly on the first ring called the ‘Outer Ring’ where those who commit violence against others and their property are punished by being submerged in a river of boiling blood called the Phlegethôn, and centaurs patrol the area, shooting arrows at those who emerge from the blood.

The song has a number of allusions to the horrors of colonial violence.

Anything But

I think this song refers to Canto 26 which establishes the critical metaphor that equates desire with flying. Here Dante encounters Ulysses - the embodiment of the epic wandering hero.

"But here one must fly, I mean with the swift wings and the pinions of great desire."

Canto 26 is critical of imperial ambitions and expansionism as Dante casts the city of Florence as a giant bird of prey whose wings beat over land and sea. This is thought as representing a specter of tyranny.

Dante presents Ulysses as the ultimate flawed hero that embodies the expression of desire as flight. Hozier expresses his desire for flight and wandering in Anything But.

I wanna be the shadow when my bright future's behind me I wanna be the last thing anybody ever sees I hear he touches your hand, and then you fly away together If I had his job, you would live forever

Abstract (Psychopomp)

Here Hozier references a childhood trauma of witnessing an animal being hit by a car and Canto 28. It's somewhat alike to the canto in a metatextual sense because it presents a gruesome picture. In Inferno 28 souls are mutilated by devils. The language is pretty clinical and graphic, like the song.

"Who, even with untrammeled words and many attempts at telling, ever could recount in full the blood and wounds that I now saw?."

The poor thing in the road, its eye still glistening The cold wet of your nose, the earth from a distance

Unknown / Nth

This one has a lot of references that have been discussed by Hozier for its allusions to the ninth circle of Hell and Cantos 34. The ninth circle is sometimes referred to as treachery but the sin is fraud.

betrayal is fraud committed against those who trust us

Hozier said he conceived of Satan/the Devil as the first prisoner of hell. I've got to link the Digital Dante article about this Canto because it's very relevant:

You know the distance never made a difference to me I swam a lake of fire, I'd have walked across the floor of any sea Ignored the vastness between all that can be seen And all that we believe So I thought you were like an angel to me

First Light

One bright morning changes all things Soft and easy as your breathing, you wake Your eyes open at first a thousand miles away But turning shoot a silver bullet point-blank range And I can scarce believe what I'm believing in Could this be how every day begins?

"Whichever day it was, it was a gentle day – mild, magical and innocent with great sailings of white cloud serene and impregnable in the high sky, moving along like kingly swans on quiet water. The sun was in the neighbourhood also, distributing his enchantment unobtrusively, colouring the sides of things that were unalive and livening the hearts of living things" - The Third Policeman

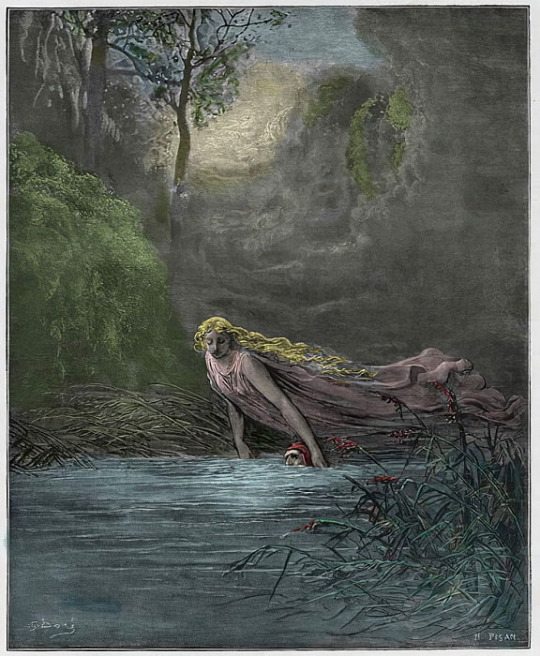

Visual imagery

"Down into the earth where dead men go I would go soon and maybe come out of it again in some healthy way, free and innocent of all human perplexity." - The Third Policeman

"Not everyone know how I killed old Phillip Mathers, smashing his jaw in with my spade." - The Third Policeman - Flann O'Brien

“If a man stands before a mirror and sees in it his reflection, what he sees is not a true reproduction of himself but a picture of himself when he was a younger man”

Reading list

“Eat Your Young”, a contemporary riff on the Irish writer Jonathan Swift’s 1729 essay “A Modest Proposal”

The Third Policeman by Flann O’Brien: an expert investigation

Bestselling author Michael Foley celebrates a comic, Kafkaesque masterpiece and explores what makes it great. But why was it cannibalised

The Irish Times

The Icarian Community Nauvoo | Paul M. Angle

Re-admitted to France, Cabet made plans to move his ideal society from the printed page to reality. In December 1847, he announced that Ic

fee.org|Paul M. Angle

An overview of the 1798 Irish rebellion

Interviews

“We betray ourselves in the act of opening up to somebody and believing so much,” Hozier says, passing a hand across his face. He looks weary, all of a sudden, voice cracking a little. “Our eyes betray us, our hearts betray us, our minds betray us. And that’s the ‘Nth’ reference: we open ourselves up to something, only to betray ourselves…”

Hell, at Least According to Hozier, Never Sounded Sweeter

On the eve of his return to the spotlight, the Irish crooner mulls over Ovid, 'Inferno,' and his status as the internet’s forest king.

Vanity Fair|Condé Nast

Hozier: ‘I think everyone goes through their version of hell’

The Irish artist is releasing his long-awaited third record ‘Unreal Unearth’, which was inspired by Dante’s Inferno. He speaks to Roisin O’C

The Independent

“There’s a subtle element and I wanted to be light and playful with it. The album can be taken as a collection of songs, but also as a little bit of a journey. It starts with a descent and I’ve arranged the songs according to their themes into nine circles, just playfully reflecting Dante’s nine circles and then an ascent at the end”

the album reflects upon two of the nine circles of hell: gluttony and heresy.

“There’s some moments that are a bit more old school and stuff that’s Nineties grunge sounding too. For other moments we were leaning into playing with a lot of synthesisers. But we’ve arranged the album into circles and the EP just represents two of those – those soul moments within it.” - Rolling Stone Interview

Divine Comedy explainers

Dante's 9 Circles of Hell: A Guide to the Structure of 'Inferno'

Here's a structural overview for the nine circles of hell in Book 1 (Inferno) of Dante Alighier's Divine Comedy.

ThoughtCo

Full Glossary for The Divine Comedy: Inferno

Absalom Bible. David's favorite son; killed after rebelling against his father: 2 Samuel 18.Acheron the River of Sorrow.Achilles Greek Mytho

cliffsnotes.com

Dante Alighieri: Mythology in the Divine Comedy

Mythology in the Divine Comedy Throughout Dante’s work “The Divine Comedy”, the author uses Greek and Roman mythology to elevate and to pro

ITAL3550SLU - Medieval & Renaissance Italian Literature

Reviews

Hozier - 'Unreal Unearth' review: Epic, expansive and ethereal

On his third album, the Irish sing-songwriter utilizes simplicity and space while venturing into new sonic territory — Read the NME review

NME|Aliya Chaudhry

Hozier: Unreal Unearth album review — solitude, spirituality and a touch of Dante | Financial Times

The singer’s roar is as impressive as ever but he also deploys other vocal styles to fine effect in his third album

ft.com

On Unreal Unearth, Hozier Makes His Boldest Work Yet

On Unreal Unearth, Hozier works through biblical source material and Dante's Inferno to make sense of isolation and human sorrow.

Paste Magazine

Hozier – ‘Unreal Unearth’ album review: A beautiful, angst-filled journey through the nine circles of hell

'Unreal Unearth' dives into the concept of Dante's Inferno.

Far Out Magazine

Unreal Unearth review | Hozier merges pop with profound prose

From the haunting echoes of Irish folklore to the pulsating beats of indie pop, this is Hozier at his artistic peak. Read our Unreal Unearth

whynow

Album: Hozier - Unreal, Unearth

Only a few artists can be said to have exploded on to the scene like Hozier. The solo, Irish musician – full name Andrew John Hozier-Byrne –

theartsdesk.com

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Realistic phoneme inventories 1: Vowels

All of the old webpages that I used to rely on for at-a-glance information about vowel systems when designing new phoneme inventories for my conlangs seem to have succumbed to various forms of link rot; and I’ve never found a good overview of how to build consonant inventories in a systematic way. So I want to set out, for my own reference and for others, an overview of both vowel and consonant systems as they tend to exist in natural languages, with an eye to creating conlangs with natural-feeling distributions of sounds.

A phoneme inventory is, of course, only one of the most basic elements of a conlang. I won’t be dealing with phonotactics, with suprasegmental features like tones, and certainly not with grammar or syntax or anything like that. A good starting point for lots of those topics is the LCK, either online or in print.

Also, phonology is not my strong suit; I’m more of a morphology person by inclination, and all my knowledge of linguistics comes essentially from years spent conlanging as a hobby. So apologies in advance if I get any terminology messed up. My primary references for this post specifically are this paper on vowel systems, this paper on consonant systems, the relevant chapters from the WALS, and conlanging resources like the LCK.

For length reasons, I’ve broken this post into multiple parts. Part 1 will deal with vowels; part 2 will deal with consonants.

1. Background information

You could, when creating a conlang, select sound arbitrarily based on what sounds pleasing to your ear, what you can easily pronounce, your favorite natural language, or your favorite IPA symbols. For conlanging as a purely artistic enterprise, those are all perfectly fine criteria; but if you want your conlang to reflect trends in natural languages--perhaps as for conlangs which are the putative natural languages of science fiction and fantasy settings--it’s helpful to understand why humans make the noises they do with their faces, and how.

The human vocal tract is a resonant column of air, stretching from the vocal cords to the lips (and nostrils, for nasal sounds), not unlike the pipe of a pipe organ, or the body of a flute. Air expelled from the lungs moves through the vocal tract and, thanks to our well-developed throat, mouth, and facial muscles, and the elaborate control over them provided by a region of the brain called Broca’s Area, we can rapidly reshape our vocal tract and manipulate the resonances of the air passing through it, producing speech.

In principle, we could make an almost infinite number of subtly different motions with our various speech-producing organs to produce an equally limitless quantity of different sounds. In practice, however, speech has to be an effective way of encoding information, or it’s useless as a communication tool. Therefore, we want sounds to be as different from one another as possible, as distinct to the ear as they can be, so they can be clearly distinguished from one another, and clearly heard over noises like wind and crackling fires and loud music. And because we talk constantly, we want speech to be as easy as possible; we are going to tend to restrict ourselves to the easiest sounds for the human vocal tract to produce.

So the IPA, the system for transcribing human speech sounds, only has about 107 basic symbols for consonants and vowels.

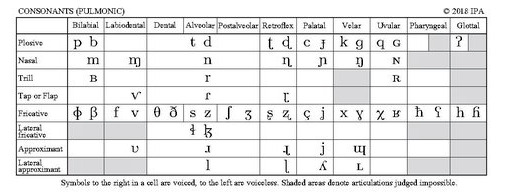

The IPA consonant chart. Shaded areas are “articulations judged impossible.” White areas with no symbol are sounds that aren’t impossible, but which aren’t widely attested in the world’s languages to need a specific transcription.

Of all the sounds covered by the IPA which actually show up in natural languages, only a small subset are truly common. Some, like the plosives /p t k/, are nearly universal. In general, the easier to produce (and more acoustically distinct) a sound, the more common it is; and languages will tend to make use of commoner sounds first (like plain plosives) as their phoneme inventory grows, before they have recourse to less common sounds (like pharyngealized plosives).[1]

The other important thing to note about phonemes is that they’re not atomic. The human brain is an extremely powerful pattern-recognition machine, and whether we’re learning our L1 as babies or learning our sixth L2 as an adult, we break languages down into many different patterns and systems as we learn them. It’s easier to learn, for instance, the general pattern that “third-person present verbs in English end in -s” than to learn, as separate pieces of information, “okay, after ‘he, she, it’ the verb ‘put’ is ‘puts’ and the verb ‘see’ is ‘sees’ and the verb ‘run’ is ‘runs’...” etc.[2] But we usually do not learn these patterns explicitly, and even when sitting down in a classroom to learn a language, there’s only so much use you can get out of memorizing a table of conjugations or declensions--it’s hard to speak fluently if you have to pause in a conversation to go, “hmm, okay, but what’s the dative femine form of the article?” Most language learning requires acquiring an intuitive grasp of the patterns of language; and you only acquire that intuition through lots of speaking and listening.

A consequence of our dependence on intuitive understanding is that two people’s intuition can differ. For instance, many people learn the rule in English that “I” is nominative, and “me” is objective; and so, unless the first person pronoun is the object of a verb or preposition, you must use “I”: “Gowron is better at Klingon politics than I.” Sometimes, this is analyzed as having an implied verb: “Gowron is better at Klingon politics than I [am].” But over the centuries of people speaking English, many people internalized a different rule. Because pronouns crop up as the objects of verbs or prepositions more than as the subjects of verbs, the objective forms came to be reanalyzed as the default forms. The nominative form became a special, marked form--one that only occured in certain cases, which was, over time, simplified into “only when the subject of a verb.” Therefore, for these speakers of English (me included), the rule became: “when appearing to the left of a verb, use ‘I’; otherwise, use ‘me.’”

Out of the steady accumulation of such petty reanalyses, great changes in grammar are born.

The same process is at work in the sounds of a language. Just like grammar, sound is heavily systematized, and encapsulated by the brain as a set of patterns. Only instead of cases or persons or numbers, the component features of sounds on which patterns are based are called their “features.” And, as with any good Saussurian principle of sign-distinction,[3] we only care about a minimal set of features which, as a community of language-speakers, we all agree are the relevant ones for distinguishing sounds. For instance, if our language has the consonant sounds /p t k b d g m n/ (the unvoiced and voiced plosives, and some unvoiced fricatives), we might need only the feature [voiced] and [nasal] to distinguish the sounds of our language. But, because we learn these rules implicitly, and we don’t have to give our youngsters a background in up-do-date phonetics research before they can say “papa”, maybe later generations of speakers, or the next village over, notices a different set of features. After all, we have to physically produce these sounds with our mouth; they don’t exist in a perfectly idealized acoustic realm. Some speakers of our language may come to see the defining feature of the voiced stops as only [+voiced], and since there are no fricatives which they can be confused with, start pronouncing them with a less constricted airflow to make them sound even more distinct from the unvoiced stops. So gradually /b d g/ become /v ð ɣ/, the voiced fricatives produced at the same place in the mouth. As far as the speakers of the language are concerned, the sounds haven’t changed--[+fricative] is not a phonemic feature of their language! The pattern isn’t changed, at least not yet. But more sound changes will accrete over time, and they may affect the new series of fricatives differently than they do the stops; and with a few more changes like this, soon you may have a version of the language that sounds completely different and is entirely mutually unintelligible.

Sound changes are 1) regular, and 2) have no memory. While sound changes can be triggered only by certain phonetic environments (say, the voicing of /p/ to /b/ between two vowels), if the conditions for a sound change are met, it will be triggered everywhere it applies.[4] And later speakers of the language won’t remember that /v ð ɣ/ used to exist in opposition to /p t k/ (unless they take a class in historical linguistics); they’ll treat these sounds on their own terms.

When the exact production of a sound varies within a language, usually altered by context due to the physiological considerations surrounding making that particular face-noise, this phenomenon is called allophony. Different versions of the same underlying sound are allophones. The sound as a unit of the formalized pattern stored in your brain is a phoneme. A phonemic transcription (between slashes /like this/) is a transcription of a sound or sounds as these abstract phonemes. A phonetic transcription (between brackets [like this]) is a transcription of a sound or sounds as something like their actual acoustic realization.

2. The vowel space and vowel planes

Consonants involve obstructing or redirecting the flow of air through the vocal tract, often entirely (as with plosives), or turbulently (as with fricatives). Combined with the large number of distinct places of articulation, involving the teeth and tongue and palate, consonants can all sound very distinct from one another. As a consequence, small consonant inventories can restrict themselves to a small subset of the full space of possible consonants, and still be fairly distinct from one another. In fact, in languages like Hawaiian or Rotokas, with very small consonant inventories ( /m n p t~k ʔ h w~v l~ɾ/ for Hawaiian and only /p t k b~β d~ɾ g~ɣ/ for Central Rotokas; the ~ symbol indicates allophonic variation between two sounds, depending on speaker or context), it’s very unlikely there’s going to be any sound that’s really difficult for a speaker of a language with a more complicated consonant inventory like English to pronounce.[5]

Vowels, though, don’t involve specific points of contact between different parts of the vocal tract in the same way as consonants; vowels are produced by the relative position of the tongue in the mouth, with an unimpeded air flow and the vocal cords engaged. This means that vowels can vary subtly--and, as a consequence, that languages tend to spread the vowels they have out, throughout the entire articulatory and acoustic space available to them, in a way they don’t have to do with consonants.

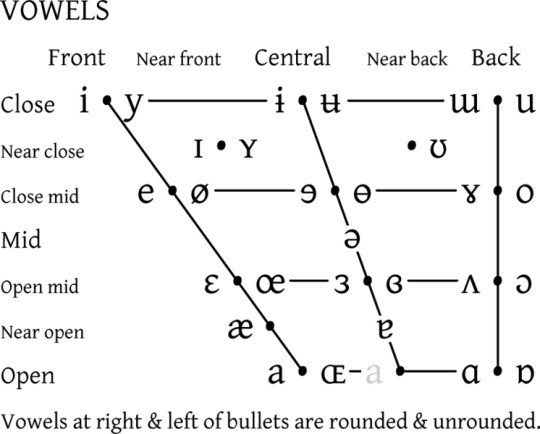

Here’s the IPA vowel chart:

The reason it’s longer at the top and on the left side is because there is more acoustic differentiation possible when the mouth is more closed versus more open, and when the tongue is more front than back. Languages will especially tend to have more close (or “high”) vowels than open (“low”) vowels. That’s not the only property that affects how vowels tend to be distributed though. Here’s a schematized diagram of the vowel space based on the actual acoustic components of the vowels:

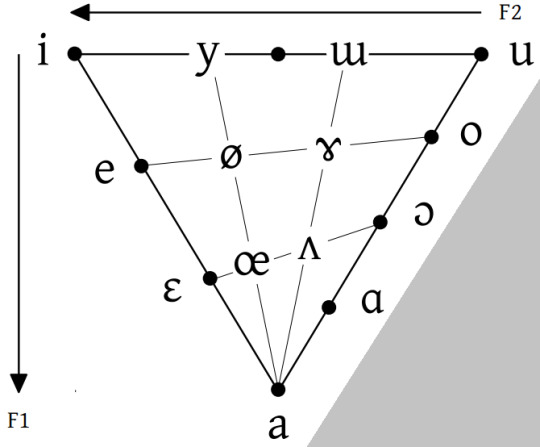

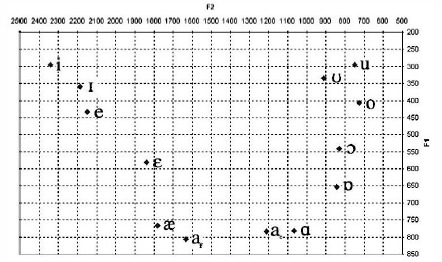

Speech sounds are composed of different-frequency elements called “formants;” the lowest-pitch formant is F1, the next-lowest F2, and so forth. For most vowels most of the time, F1 and F2 are the really important formants. Open vowels have higher first formants, and close vowels lower first formants; front vowels have higher second formants, and back vowels have higher low formants. Here’s a similar chart, showing actual values, from the Hitch paper:

But we don’t recognize vowels just using their pitch. If it did, we could in theory have languages with hundreds of vowels: the ear and brain together can detect extremely subtle gradations of tone. Rather, what matters more is the relative value of vowels, the distinctive features like [+front] or [-high].

Most languages have small vowel inventories; in terms of the psychological perception of vowels, the vowel space is quite small. WALS classified any language with 4 or fewer values as “small,” languages with 5-7 vowels as “average,” and any language with more than 7 as having a “large” vowel inventory. Germanic languages like English, which have anywhere from 10 to 17 (!) vowels, are monstrously bloated by global standards. Usually for larger vowel inventories, additional features will be added besides the spatial features so that vowels don’t have to compete for space: Latin doubles its vowel inventory (/a e i o u a: e: i: o: u:/) by adding a length feature, and Turkish (/i y ɯ u ɛ œ a o/) accomplishes something similar with rounding.

Additional sets of distinctions like these, which are not spatial distinctions, create different vowel planes, where vowels do not have to compete for space with one another directly. Vowel planes may be parallel (as in Latin or Turkish), or not. There may be phonological or grammatical processes that trigger vowels moving from one vowel plane to another, as languages with vowel harmony, where vowels in a word must share a particular feature like frontness or roundedness, or vowel planes may simply exist to provide additional acoustic contrast within a language’s vowel inventory.

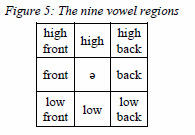

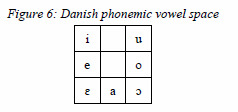

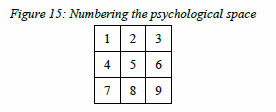

Traditionally, languages with large vowel inventories have been analyzed as having many degrees of front/back or height distinction: four, in languages like Danish, or even sometimes five, as in the case of one Bavarian dialect Hitch cites in his paper. However, Hitch argues that the psychological space available for the vowel plane is really divided by reference to a perceived “neutral” vowel, one that may not be phonemic in a language, but will still crop up in paralinguistic utterances (like English “ugh” or “uh-huh”). It is by comparison to this vowel that vowels acquire distinctive spatial features, and as such, there are really only nine ways, at most, to divy up the vowel plane:

No language, in Hitch’s analysis, really has more than three distinctions of height or backness. When you think you have more, as in Danish, it’s time to take a look at the possibility that some apparently spatial feature really reflects an underlying contrast that isn’t spatial. Remember, it’s only the phonemic features of a sound that are fixed: the non-phonemic features can vary, sometimes by quite a lot.[6] Anything higher and fronter than the neutral vowel will count as a “high front” vowel, and its exact spatial realization may not be the same in each vowel plane.

Danish, for instance, has the vowel inventory /i e ɛ a y ø oe u o ɔ/ and is analyzed as Hitch as having the primary vowel plane

The three front rounded vowels /y ø oe/ form a distinct plane, one in which the only distinctive feature is height: high round, mid round, low round. The “frontness” of these vowels is a phonetic feature, but not an important phonemic feature. They don’t contrast directly with the rounded back vowels, because back vowels are usually rounded--it makes them more acoustically distinct from mid vowels, and round back vowels show up in tons of languages, like Latin, that don’t make a phonemic contrast for rounding. And rounding has a side effect on front vowels, making them sound a more central: thus, the “front round plane” is, perceptually speaking, more of a mid round plane distinguished by the [+round] feature. Languages can have multiple secondary planes. According to Hitch, Jalapa Mazatec “may have six parallel planes.”

Vowel harmony doesn’t have to operate across planes: Hitch provides the example of the three-vowel language Jingulu, which as /a i u/. A suffix in /u/ or /i/ will raise the preceding vowel unless a high vowel intervenes: bardarda, “younger brother” + -rni > birdirdirni, “younger sister.” But if often does, with apparent height distinctions being better understood as plane distinctions: “In these languages, the vowels in a particular word will all be from one plane or the other. It seems that the choice of plane is determined at the lexical level. In the lexicon, the words contain archiphonemes spanning both planes, and each word is marked with a feature indicating plane membership.”[8] Even if a language doesn’t have clearly non-spatial articulatory features distinguishing its planes like nasalization or length, it can still have two vowel planes that exist side by side. For Ogbia, a language of Nigeria, Hitch gives two vowel planes corresponding to one with the advance tongue root feature (+ATR) /i e u o ɐ/ and one without (-ATR) /ɪ ʊ ɛ ɔ a/. For Nez Perce, five surface vowels /i u o æ ɑ/ correspond to two planes /i u æ/ and /i o ɑ/; a word can have vowels from one plane in it, but not both. /i/ happens to exist in both planes (possibly due to a merger of two distinct underlying vowels).

3. Vowel systems

So for any vowel system on a single plane, we’re going to have a maximum of nine vowels. Secondary systems may be the same size as the primary vowel plane; or they may be smaller. Either way, our vowel systems will tend to have one of two shapes, triangular or rectangular. In a triangular vowel system, acoustic considerations are dominant. We will have fewer open vowels, and more close vowels. In a rectangular vowel system, the psychological considerations are instead dominant, and vowels will be distributed in the nine-vowel grid in a more symmetric fashion.

These nine potential positions or “archiphonemes” don’t always reflect the same division of the vowel space given on the IPA. 7 and 9, for instance, might be open-mid vowels rather than true open vowels. 2 might be a rounded front close vowel. 5 may or may not be a schwa. 8, the bottom of the IPA trapezoid or the idealized acoustic triangle, is usually [a], despite [a] being, tecnically, a front vowel! I will simply quote Hitch at length here:

With those caveats, we can then look at the possible arrangements of vowel systems, from zero vowels to nine.

Zero vowels. “A zero-vowel language would insert vowels according to rules of epenthesis, then colour the vowels according to phonetic context. It sounds theoretically possible, but no completely convincing cases have yet been identified.”

One vowel. “There would seem to be no indisputable examples of one-vowel systems on a primary plane.” But there are languages with one-vowel secondary planes. If a language has one long vowel, for instance, it will be /a:/. But if a language has one nasalized vowel, it can be just about anything.

Two vowels. This includes languages with a two-vowel front round plane; also, languages with a primary plane that has just a height distinction. All Northwest Caucasian languages have /ə a/ (but feature lots of allophones). Most examples Hitch cites for two-vowel systems have some kind of central vowel (/ə/ or /ɨ/) plus /a/; but Witchita has /i a/. “But this type reveals something fundamental about vowels: that [low] is the most basic of the four spatial features.”

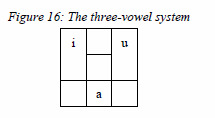

Three Vowels. The triangular system /i u a/ is a very common system among the world’s languages, with /i/ and /u/ having lots of vertical freedom.

Hitch is very down on the idea of a three-vowel on the primary plane; of the potential examples he cites, none are undisputed. But “Parisian French has a vertical three-vowel configuration /y ø oe/ on a front-rounded plane (primary /i u e ə o ɛ a ɔ/). While vertical three-vowel systems may not exist, primary plane triangular three-vowel systems are exceedingly common.”

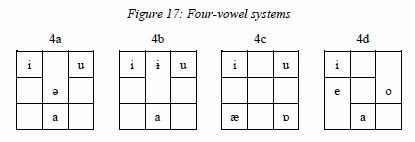

Four vowels. The triangular 4-vowel systems (4a and 4b) add a neutral vowel to the classic 3-vowel system. A straightforward rectangular system is possible (4c); as well as a slightly more complicated variation with more room for allophony (4d).

He also gives the unusual example of the Lummi dialect of North Straits Salish, which “appears to have no low vowels” /i e ə o/, though this is clearly an outlier.

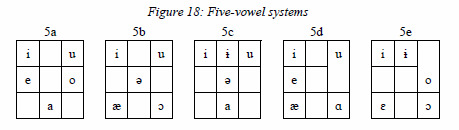

Five vowels. The Latin vowel system (5a) is an extremely common triangular system; a rectangular 5-vowel system is also pretty common (5b). Three other five-vowel systems are given that are “relatively rare,” being a triangular system that combines 4a and 4b (5c), a 4c-like rectangular system with a mid front vowel added (5d), which is “asymmetrical, because the acoustic space is dominant,” and a different variation on 4c that instead adds a high central vowel. As an unusual exception, Hitch notes that Tohono O’odham “appears not to fit the pattern of any other language, and to violate a universal by having more back than front vowels with /i ɨ u o a/.”

Six vowels. Adding a central mid or central high vowel to 5a gives two common triangular six-vowel systems (6a and 6b). A rectangular six-vowel system, with no central vowels, is also possible.

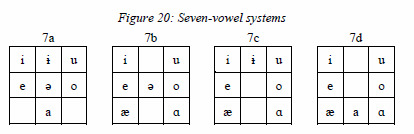

Seven vowels. There is one possible triangular configuration, 7a, with one low vowel. Otherwise, 7-vowel systems are rectangular systems that differ only on where they place the central vowel.

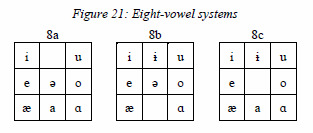

Eight vowels. Similarly restricted: there are only three possible configurations of eight vowel systems, depending on which central vowel is omitted. None appear to be very common, however.

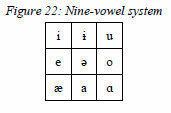

Nine vowels. Nine is the maximum number of vowels on a single plane, and therefore there is only one nine-vowel configuration possible. All analyses of more than nine “basic” vowels means you should start examining the possibility of multiple vowel planes.

In the next post, we’ll take a look at consonant systems.

Footnotes:

[1] https://wals.info/chapter/1 (ctrl+f “size principle”)

[2] Languages do have irregularities, where historic patterns have been obscured by sound change or other processes. But there’s a reason irregularities or fossilized forms tend to occur in commonly-used words and phrases rather than rarely used ones: it is harder to remember variant patterns for rarely used words, and so they tend to become regular by analogy.

[3] Cf. Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics. This is one of those texts that was mind-blowing to me when we read it in our Critical Theory course in undergrad, but now seems so obvious as to not be worth discussing. The key insight can be summed up very succinctly, though: human brains care about differences between symbols, not their absolute values. When it comes to the kind of meaningful differentiation required for communication, it’s the relative differences between signs that matter--so any sign-system can be simplified to the minimum required number of distinctions, without the loss of information or without impeding communication. This insight is relevant to everything from linguistics to information theory.

[4] Apparently irregular sound changes--why does the Early Modern English sound spelled <gh> get pronounced as /f/ in “enough,” but is silent in “through”?--are usually the result of patterns being obscured by analogy or borrowing. In this case, it’s because the prestige dialect of English that coalesced around London in the Early Modern period, and was influenced by speakers of English from all over England, sometimes borrowed words from other dialects that had undergone different sound changes. In some of those dialects, the <gh>-sound was lost. In others, it changed to /f/.

[5] The only sounds in either Rotokas or Hawaiian given above that don’t crop up as a phoneme or allophone in English are probably [β ɣ]. The former is just [v] pronounced with only the lips; the latter, the voiced equivalent of German or Scottish [x].

[6] For instance, the Middle English long vowels /iː eː ɛː aː ɔː oː uː/, had as their distinctive feature their length, not the exact contour of their sound. That meant that these long vowels could “break,” becoming diphthongs, but as long as they remained mostly distinct from one another, no confusion resulted. That breaking, plus the general reorganization of the vowel system that changed the pitch of the pure long vowels (the high ones, which could not acquire a high offglide because there was no space above them acoustically) later yielded the corresponding modern long vowels /aɪ i: i: eɪ aʊ u: oʊ/

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

The great revelations of Jamie Lloyd's Pinter at the Pinter season have sprung from the way the director has taken all the author's short works and made plays that have been rarely seen seem suddenly essential. In looking at them afresh, he has brought them to life.

The revelation of his concluding production of Betrayal – not quite a short play, but certainly a concise 90-minutes – is to take a play that has become very familiar and make it unfamiliar and strange. What can often seem like a naturalistic description of the corrosive effects of a seven-year secret on a marriage and a friendship, which is distinguished mainly because it begins at the end and unfolds backwards, suddenly seems a chillier, darker piece. Lloyd has scraped off all the surface accretions and with the help of a devastating performance from Tom Hiddleston, uncovers the raw passion and terror beneath.

The freshness of the approach is clear from the opening scene. As Emma (Zawe Ashton) and Jerry (Charlie Cox) sit on chairs, having drinks, discussing the affair they once had behind the back of her husband and his best friend Robert (Hiddleston), Hiddleston actually stands at the back of the stage, like a dark figure of accusation and betrayal.

From then on, the triangle of their tangled relations doesn't remain an abstract notion, it is a physical presence, a brooding shadow that affects even the simplest of gestures. The three actors stand on a revolve and literally circle one another, like gladiators before a fight, sometimes speaking and present, sometimes silent, but never absent.

For example, one of the leitmotifs that runs through the play is Jerry's memory of throwing Emma and Robert's daughter Charlotte in the air. Here we see the act – the child caught, laughing. Throughout the subsequent scene, where Emma and Jerry meet in their love nest, Robert circles the stage, his daughter asleep in his arms.

The effect is like being plunged into the inside of someone's mind – somewhere between nightmare and memory. It's emphasised by Soutra Gilmour's neutral set, its marbled walls conjuring trendy living rooms and the streets of Venice with a minimal and stylised effort. Jon Clark's lighting is similarly both realistic and symbolic, full of shadows and sudden shafts of sun.

Lloyd directs to emphasise the silences, the long pauses where the trio simply look at one another, their faces full of feeling, their hearts full of passion, anger, despair, and doubt. Cox rises brilliantly to the challenge of sitting absolutely still and speaking volumes while saying not a word. His Jerry is a weak, charming man who seethes with the need to be loved, his constant half smile and warm eyes begging for forgiveness, absolution, understanding.

But it is the casting of Hiddleston in the traditionally less showy part of Robert that is the revelation. Betrayal is famously based on Pinter's long affair with the broadcaster Joan Bakewell, but time – and Bakewell's own commentary – have altered our view of the character of Emma and Zawe Ashton – all restless gestures and constant unhappiness – struggles to give her much force. At this distance, Betrayal feels less like a portrait of the destructive power of love and more like a study of men at bay, baring their souls under the veneer of not caring.

In this context, the long central section where Robert discovers Emma's betrayal through the arrival of a letter acquires astonishing weight and Hiddleston charts each moment of discovery. In the early part of the play, he has been all clipped control, delivering even the shocking line about hitting Emma – "the old itch"- with cold contempt.

But here we see the moment of his disillusion, and his pain, hardening to anger, to a fake casualness that is astonishing to watch. His eyes fill with tears and the emotion is almost overwhelming. The subsequent scene where he encounters Jerry over lunch, and disguises his feelings with ferocious eating and drinking, is simultaneously comic and heart-rending, wonderfully observed. It is a performance full of easy charisma and intense truth.

It makes the play boldly bleak, an examination of the human condition as savage as any offered by Samuel Beckett, full of torrents of language that sound like poems, and spaces between things that suggest a void. It is Betrayal as I've never seen it before, and like this entire season, it bathes Pinter in a brilliant new light.

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review: Betrayal (Harold Pinter Theatre)

"The great revelations of Jamie Lloyd's Pinter at the Pinter season have sprung from the way the director has taken all the author's short works and made plays that have been rarely seen seem suddenly essential. In looking at them afresh, he has brought them to life.

The revelation of his concluding production of Betrayal – not quite a short play, but certainly a concise 90-minutes – is to take a play that has become very familiar and make it unfamiliar and strange. What can often seem like a naturalistic description of the corrosive effects of a seven-year secret on a marriage and a friendship, which is distinguished mainly because it begins at the end and unfolds backwards, suddenly seems a chillier, darker piece. Lloyd has scraped off all the surface accretions and with the help of a devastating performance from Tom Hiddleston, uncovers the raw passion and terror beneath.

The freshness of the approach is clear from the opening scene. As Emma (Zawe Ashton) and Jerry (Charlie Cox) sit on chairs, having drinks, discussing the affair they once had behind the back of her husband and his best friend Robert (Hiddleston), Hiddleston actually stands at the back of the stage, like a dark figure of accusation and betrayal.

From then on, the triangle of their tangled relations doesn't remain an abstract notion, it is a physical presence, a brooding shadow that affects even the simplest of gestures. The three actors stand on a revolve and literally circle one another, like gladiators before a fight, sometimes speaking and present, sometimes silent, but never absent.

For example, one of the leitmotifs that runs through the play is Jerry's memory of throwing Emma and Robert's daughter Charlotte in the air. Here we see the act – the child caught, laughing. Throughout the subsequent scene, where Emma and Jerry meet in their love nest, Robert circles the stage, his daughter asleep in his arms.

The effect is like being plunged into the inside of someone's mind – somewhere between nightmare and memory. It's emphasised by Soutra Gilmour's neutral set, its marbled walls conjuring trendy living rooms and the streets of Venice with a minimal and stylised effort. Jon Clark's lighting is similarly both realistic and symbolic, full of shadows and sudden shafts of sun.

Lloyd directs to emphasise the silences, the long pauses where the trio simply look at one another, their faces full of feeling, their hearts full of passion, anger, despair, and doubt. Cox rises brilliantly to the challenge of sitting absolutely still and speaking volumes while saying not a word. His Jerry is a weak, charming man who seethes with the need to be loved, his constant half smile and warm eyes begging for forgiveness, absolution, understanding.

But it is the casting of Hiddleston in the traditionally less showy part of Robert that is the revelation. Betrayal is famously based on Pinter's long affair with the broadcaster Joan Bakewell, but time – and Bakewell's own commentary – have altered our view of the character of Emma and Zawe Ashton – all restless gestures and constant unhappiness – struggles to give her much force. At this distance, Betrayal feels less like a portrait of the destructive power of love and more like a study of men at bay, baring their souls under the veneer of not caring.

In this context, the long central section where Robert discovers Emma's betrayal through the arrival of a letter acquires astonishing weight and Hiddleston charts each moment of discovery. In the early part of the play, he has been all clipped control, delivering even the shocking line about hitting Emma – "the old itch"- with cold contempt.

But here we see the moment of his disillusion, and his pain, hardening to anger, to a fake casualness that is astonishing to watch. His eyes fill with tears and the emotion is almost overwhelming. The subsequent scene where he encounters Jerry over lunch, and disguises his feelings with ferocious eating and drinking, is simultaneously comic and heart-rending, wonderfully observed. It is a performance full of easy charisma and intense truth.

It makes the play boldly bleak, an examination of the human condition as savage as any offered by Samuel Beckett, full of torrents of language that sound like poems, and spaces between things that suggest a void. It is Betrayal as I've never seen it before, and like this entire season, it bathes Pinter in a brilliant new light."

#betrayal#harold pinter theatre#tom hiddleston#zawe ashton#charlie cox#pinter 8#pinter at the pinter season#jamie lloyd production#harold pinter play betrayal#theatre tom#tom hiddleston stage performance#betrayal press night#betrayal review#march 13#hiddles 2019#tom hiddleston as robert#whats on stage

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Inquiry Into Fear

Driving down the short, steep grade into the canyon just beyond town, I passed a score of young people with shovels and buckets, obviously returning from trail work. From that point on I saw no one in three hours.

I parked in the last parking area before the locked gate at the end of the bumpy, gravel road. It’s less than a half-mile walk into the gorge, affording a stupendous view for meditation.

The “Diablo” winds from north to south have ceased in recent days, and smoke from the fires in wine country to the south have blanketed the skies in northern California in an otherworldly haze.

The hills are now bone dry, and desolate beyond description. Normally I welcome, even relish solitude, but there was something unearthly in the atmosphere that brought forth deep fear.

Photo Martin Lefevre

The combination of tinder-dry hillsides, total solitude, and miasma lent a dreamlike quality to the experience. It was no daydream however, but reality, outwardly and inwardly—without the division between “outward” and “inward.”

Except for one unseen plane, there wasn’t a sign or sound of humans and the man-made world for hours. Due to the physical and metaphysical conditions, I felt more alone than I ever have except while backpacking by myself. But was I alone?

If you’ve ever spent a night or two in the wilderness alone, you know there is a primal fear at the core of human consciousness.

Though it’s been a long time since I backpacked alone, I recall the ancient fear and chaotic mental activity the solitude induced on the first night. Why did I put myself through it?

At a deep level I wanted to stand alone and face fear. Not just ‘my fear,’ but fear itself.

Sure enough, after two days and nights of remaining with what is, psychological fear dissolved, like a bad dream on a beautiful morning.

Sitting on the lip of the gorge yesterday, a question I read earlier in the day came to mind: Is it that the whole structure of the cell is frightened of not being?

I don’t think the cells themselves are frightened of not being. Even the lowliest insect is imbued with a survival instinct, which, when confronted with danger, incites the flight or fight response. So fear is part of the survival instinct that is intrinsic to every living thing.

The questions, it seems to me are: Do we humans tend to live in fear because we’re social animals? Is fear intrinsic to the neo-mammalian brain dominated by symbolic thought?

Certainly the fear of standing alone, or even being alone for a few hours in nature, is linked with our social natures. Is fear the essence of conformity?

For tens of thousands of years, being cast out from the group into the wilderness meant almost certain death. There’s a subconscious memory of that fear, which infuses and confuses us in the modern world much more than we think.

Photo Martin Lefevre

In short, fear a necessary survival reaction in animals, but an unnecessary psychological condition in humans. It isn’t the condition of life that produces fear, but the accretion of conditioning that produces fear.

Isolation and loneliness lie at the root of fear within us. Of course there is the fear of poisonous snakes, for example, which is both instinctual and learned (the latter being fitting or phobic). But I’m referring the deep need to be part of a group, and the inability to be truly alone.

The root meaning of the word alone is “all one.” Initially what I experienced in the desolate canyon beyond town was not aloneness, or even solitude, but isolation and loneliness. This is what gave rise to fear.

Fear was the theme of the day, since I also read this bit of inanity yesterday: “Fear causes people to privilege psychological security over liberty.”

That evinces not only an utter lack of understanding of fear, but also a failure to perceive the fact that there is no such thing as psychological security. The need for security destroys security, for oneself and for others.

Psychological thought, fear and time are inextricably related, and form a single movement. Solitude, aloneness and isolation are distinct, though easily confused and conflated qualities of being.

Solitude is essential to aloneness, as all-oneness. Paradoxically, watchful solitude is also necessary to uncovering and transcending isolation, loneliness and fear.

When solitude brings forth loneliness, observe it and remain with it. Then solitude is the soil that engenders freedom from loneliness and fear, and opens the door to the sacred.

Martin LeFevre

An Inquiry Into Fear syndicated from http://ylangylangbeachresort.com/

0 notes