#the entire series is referencing her and her presence is felt all over every single book

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the locked tomb is literally the most haunted narrative i have ever witnessed. you cannot point at any single character, and say "this is their story", because everyone else is touching and has touched the story in some way. every character has their fingerprints all over the story. everybody's a ghost and they're all haunting these books.

that's because you're not reading one story. you're reading an entire universe of stories, some of which have already played out, some of which are actively playing out somewhere where you can't see them. you can smell and taste and sense these stories all over the one you're actually being told.

everytime a character dies or fails to die or dies in all ways except physical, they start haunting the narrative too. the original lyctors have been haunting the narrative since gideon the ninth, wake and alecto were both quite literally haunting harrow the ninth, both of the first two books are haunting nona the ninth. i can only assume alecto the ninth is going to be the book where we confront the ghosts.

and it's not just the narrative being haunted. individual characters are haunted by other characters. griddlehark are haunting each others' narratives. same with the tridentarii. john's somehow haunted by himself, which is impressive, and kind of overkill, considering all the other characters he's also haunted by, including the earth herself.

there are so many possible interpretations as to whose story the locked tomb is, and all of them are equally correct, because the story itself doesn't seem to know, and i mean that in the best way possible. i mean that in the way that this could be the story of two kids who grew up together. this could be the story of what happened to those two kids, or of what happened long before either of them were born. this could be a story, where everyone's story is actually about someone else.

everybody can have their own opinions. personally, i like the idea that the thing haunting this story the most is what we see in the john chapters of nona the ninth: two beings stuck in an endless loop of making and remaking each other. and they're in love. and they will be and already have been the death of each other. that feels very on brand for this series.

#what im saying is wouldnt it be cool if atn was just an exorcism for the narrative#get all those ghosts out of the narrative and into the story!!#get cassiopeia in there!! fuck it. get all the original lyctors in there!!!#griddlehark reunion so they can finally stop haunting each others' narratives??#and alecto at the center of it all. because she is the ultimate haunter of the narrative#the entire series is referencing her and her presence is felt all over every single book#and yet this'll be her first real appearence as herself. not as nona. not as a memory or a hallucination.#she will finally be a character in the story about her.#tlt#the locked tomb#tlt spoilers#the locked tomb spoilers#gtn#htn#ntn#atn#gideon the ninth#harrow the ninth#nona the ninth#alecto the ninth#gtn spoilers#htn spoilers#ntn spoilers#alecto speculation#fritz rambles too much

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pretentious and Cringy: RoseBlood

For our very first condemnation to this library, we are given RoseBlood by A.G. Howard. Follow the read more for a full count of its sins and stupidity. Warning: it gets long.

This doesn’t count as a sin but great Satan the damn description is way too long! This was likely not the author’s choice though which is why it gets a pass.

This YA novel from New York Times bestselling author A. G. Howard marks the beginning of a new era for fans of the Splintered series. Rune Germain moves to a boarding school outside of Paris, only to discover that at this opera-house-turned-music-conservatory, phantoms really do exist. RoseBlood is a Phantom of the Opera–inspired retelling in which Rune’s biggest talent—her voice—is also her biggest curse. Fans of Daughter of Smoke and Bone and the Splintered series will find themselves captivated by this pulse-pounding spin on a classic tale. Rune, whose voice has been compared to that of an angel, has a mysterious affliction linked to her talent that leaves her sick and drained at the end of every performance. Convinced creative direction will cure her, her mother ships her off to a French boarding school for the arts, rumored to have a haunted past. Shortly after arriving at RoseBlood conservatory, Rune starts to believe something otherworldly is indeed afoot. The mystery boy she’s seen frequenting the graveyard beside the opera house doesn’t have any classes at the school, and vanishes almost as quickly as he appears. When Rune begins to develop a secret friendship with the elusive Thorn, who dresses in clothing straight out of the 19th century, she realizes that in his presence she feels cured. Thorn may be falling for Rune, but the phantom haunting RoseBlood wants her for a very specific and dangerous purpose. As their love continues to grow, Thorn is faced with an impossible choice: lead Rune to her destruction, or save her and face the wrath of the phantom, the only father he’s ever known.

That first paragraph would have sufficed for description and given the reader some mystery. The second could have stayed but it’s on thin ice. And we don’t have ice in hell.

To summarize the story: Rune Germain is a 16-17 year old girl from Pleasant, Texas who is, in her own words “possessed by music”. Thanks to a rich aunt and some nepotism, she gets the chance to go to RoseBlood, a conservatory in Paris that is a refurbished opera house that, according to Rune’s online research, is the place where Gaston Leroux’s Phantom Of The Opera story really took place. Upon arrival, Rune is immediately overtaken by music and makes an enemy in Katrina Nilsson by interrupting Kat’s audition for Renata in the school’s opera. She also makes friends with a few other students who really have no bearing on either the plot or Rune’s adventures. She eventually finds her Love Interest Thorn - real name Etalon, stalking her as she goes about her day to day life, and immediately falls in love with him because they are Twin Flame and Destined by Destiny. It is soon enough revealed that Rune, Thornalon, and Erik are all psychic vampires that must feed off humans to survive. It is also soon revealed that Rune and Thornalon are Christina Nilsson’s soul reincarnated and split and that Rune “has Christine’s voice”. It also turns out that Christina and Erik got married and tried to have a child who was born premature and died. Erik was driven mad(der) by the child’s death and somehow, in the 1900′s, managed to build a contraption that kept the baby “alive” until he could track down Christine’s soul and reunite the pieces and transfer it to the baby... Needless to say, he failed, Rune and Thornalon live happily ever after, and Rune suffers no consequences from any of her terrible actions through the whole novel.

Sin count time!

Sin 1: The school name! RoseBlood. What does it have to do with anything? There are bleeding roses later in the story but why would a school name itself RoseBlood? This choice is never explained. It has no French basis, no connection to the opera-house turned school, and no connection to Gaston Leroux’s original Phantom Of The Opera.

Sin 2: Overwrought descriptions right out of the gate.

At home, I have a poster on my wall of a rose that’s bleeding. Its petals are white, and red liquid oozes from its heart, thick and glistening warm.

Mom looks out her window where the wet trees have thickened to multicolored knots, like an afghan gilded with glitter.

I trace the window now curtained by mud, imagining the glass cracking and bursting; imagining myself sprouting wings to fly away through the opening—back to America and my two friends who were tolerant of my strange quirks.

These are all from chapter one. It only gets worse as you go.

Sin 3: Racism. Main character Rune Germain regularly describes herself as a “gypsy”. According to her, on her father’s side, she’s a g*psy. Moving through this review, I will be censoring the word. I’m a demon of hell, not a piece of shit. Rune never says Roma or Romani in the entire book. There’s no references to Romani culture, nothing about the problems Romani people face in the modern day, nothing. Rune is also as white as a piece of paper. You can see it on the cover

And in how she describes herself.

People say we could pass for sisters. We share her ivory complexion, the tiny freckles spattered across the bridge of her nose, the wide green eyes inside a framework of thick lashes, and her hair—black as a raven’s wings.

If you look up pictures of Romani people, you see that they’re far from ivory skinned.

It’s not only Rune. Her Aunt Charlotte does it too. The “Phantom” does it. And Roma culture is treated very poorly throughout the novel. Rune several times refers to her “g*psy blood” as “cursed” or “terrible”. One example:

Nausea sweeps through me at the thought. After our encounter, I realized why I was enchanted by the spider’s feeding rituals, that there was something in my g*psy blood—something tainted and wrong.

In this modern day and age, can’t humans stop demonizing and stereotyping an entire culture? Or using “half-g*psy” lineage to make characters “exotic” or “mystic”? No? Fine, I’ll see you down here eventually.

Sin 4: The Love Interest’s backstory..... TRIGGER WARNING FOR FURTHER DISCUSSION OF RAPE, CHILD TRAFFICKING, AND REFERENCED CHILD SEXUAL ASSAULT.

Rune’s Love Interest is named Etalon. His mother was sexually assaulted by a psychic vampire who is apparently from Canada - I have no idea why Howard felt the need to include that - and it ruined her life to the point where she was forced to turn to prostitution to feed herself and Etalon. A man kept trying to “buy” Etalon from her because he was beautiful. She kept refusing, and eventually, she was murdered. Etalon was quickly snatched up into child trafficking where, at one point, he was forced to drink lye water to damage his vocal cords because he wouldn’t stop singing. He eventually escaped when Erik found him and took him in, renaming him Thorn.

Love Interests with tragic backstories are a staple of the YA genre. It makes them mysterious and interesting. It often drives the main character’s interest in the aloof and unusual bad boy. Quite often, these backstories involve dead or missing parents, being turned into a vampire or werewolf, or some combination of all of these things. It’s very rare that it gets so real. Child trafficking is a very real and prevalent issue in the world and it needs attention brought to it. But not like this. Using it as a character’s backstory is something that takes a level of skill Howard simply does not have. It needs to be written with respect to victims who might read it and not just be used to give characters a compelling but otherwise unused backstory. Thornalon never displays any indicators that the time spent in this situation traumatized him. There’s no signs of PTSD or other mental health issues that might arise from what he went through. There’s also no signs that Howard donated any money from book sales to charities like Child Fund, Save The Children, or ECPAT-USA. This is a very serious topic that NEEDS more attention brought to it and Howard glossed over it like it was nothing.

Sin 5: Underutilized setting. Rune comes from Pleasant, Texas and moves to Paris, France. But there’s no sense of wonder from her. She never talks about how beautiful the city is or learning French. Supposedly, the school only admits American students.

“How many foreign boarding schools offer admittance only to American kids? This is a rare opportunity . . . a taste of French culture in a setting that feels like home.”

Oooor the author couldn’t be bothered to deal with French translations or expanding the student body to include a diversity? There’s no French culture anywhere in this book. Any time Rune goes into Paris, it’s skipped over. There’s nothing about it that says Paris. It could have been set in New Jersey and it wouldn’t have made much of a difference.

Sin 6: Each chapter begins with a quote from a different author and work. Including, weirdly enough, Karl Marx... Beginning a chapter with a quote is fine, but it should be consistent. Picking a single work or author to use helps to reader see a consistency in the theme of the book. Since this is a Phantom of The Opera based story, it would make sense to use quotes from the book. Instead, the author uses a different work for each chapter, and it’s honestly just annoying.

Sin 7: All promise, no pay off. This book has a promise of action and mystery. It’s got a fabulous premise and a setting that could be beautifully used if in the hands of the right author. But it misses the mark on good characters, action, and keeping a consistent pace.

Punishments: For being tone-deaf and generally bad at writing, author A.G. Howard is condemned to have the dead tree in her backyard become home to her state’s buzzard population. For being a terrible protagonist, Rune Germain is condemned to find a mistake in the middle of her knitting projects just as she is about to finish them. For the terrible Phantom Iteration known as Erik, we condemn his instruments to always be just slightly out tune. And Thorn/Etalon... we order you to get a lot of therapy and a service dog.

So let it be recorded. Today’s story time is concluded.

#roseblood#ag howard#book snark#the library of hell#bad books#bad writing#roseblood ag howard#the phantom of the opera#phantom of the opera#tw child trafficking#tw rape#racist writing#g*psy slur use

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anya Taylor-Joy Infiltrates the Boys’ Club of Chess in The Queen’s Gambit

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

Netflix’s period piece miniseries The Queen’s Gambit spans a decade in the life of fictional chess prodigy Beth Harmon (Anya Taylor-Joy), a wunderkind whose natural aptitude for anticipating her opponents’ moves is blunted by her addiction to the tranquilizer pills with which she credits her wins. Following gawky teenage Beth through her early tournaments in the 1950s to the aloof redheaded beauty wowing spectators in Europe in the ’60s—and leaving a trail of defeated men in her wake—the seven-hour series was faced with the challenge of making every chess scene equally thrilling to enthusiasts and non-fans alike.

The key, Taylor-Joy explains to Den of Geek, was in having every single game be recognizably unique. “[Series creator and director] Scott [Frank] and I would have a lot of conversations about both the chess and the addiction scenes, and how we were going to make each of them different and each of them fresh,” she says. “Because this show is seven and a half hours, and if a lot of that is the same chess game, people are gonna wander off.”

The cast and crew imbued each chess match with specific emotion, matching Beth’s personal and professional growth, and unique physicality. For the latter, that involved bringing in chess consultant Bruce Pandolfini (who also consulted on Walter Tevis’ 1983 novel on which the series is based) and grandmaster Garry Kasparov to plan out the series’ many games down to every gambit and checkmate. Because neither Taylor-Joy nor her on-screen competitors had played much chess prior to shooting, treating the gameplay as choreography helped them pick up the moves.

“I saw the whole thing as a dance,” explains Taylor-Joy, a former ballet dancer. “I saw learning the choreography as dance, but just with your fingers.”

Costar Harry Melling, who plays one of Beth’s early rivals Harry Beltik, agrees that the authenticity was found in the tactile movements of the pieces themselves.

“One of the most important things in terms of the choreography was the feel of the pieces,” he says, “about how you take pieces—whether you slide it across the board or whether you lift it up or put it down. All of these little details [are] what makes it look like you��ve been doing it your entire life.”

“It’s like riding a horse,” says Thomas Brodie-Sangster, whose chess champion Benny Watts is known for a distinctive leather duster and laconic attitude. “It doesn’t really matter if you can ride a horse, it’s more about if you can get on the horse and get off the horse and look cool doing it. That’s what people pick up on; it shows that you actually look comfortable doing it.”

While Beltik and Benny are as fictional as Beth, the actors were encouraged to draw inspiration from current and historical grandmasters on which to base their characters’ games. “Every game in the show is based on a real game,” Brodie-Sangster says. “If you’ve got a really keen eye, you can probably recognize games from across the history of chess.” He modeled Benny’s moves after Bobby Fischer, while Melling devoted a lot of time to watching current World Chess Champion Magnus Carlsen play.

“That was really fascinating,” Melling says, “because I knew nothing about chess whatsoever—so [I was] starting from ground zero, really, working out how these people operate, what makes them tick.”

Equally important as the dance steps were the dance partners. Taylor-Joy credits the originality of each sequence to who Beth is playing at that moment in time—like Townes (Jacob Fortune-Lloyd), a hunky competitor who flusters young Beth. “The first time that Beth plays Townes, it’s the first time that she’s ever liked somebody that she’s playing opposite against,” she says, “so she wants to win, but she doesn’t necessarily enjoy seeing him crumble, which is a new experience for her.”

Taylor-Joy soon found the game as dramatic as Beth does. “For her, it is life or death,” she says. “This is her intellect being challenged, and her intellect is the only thing she has any faith in. So I definitely felt the pressure, and then—whenever she’s playing with somebody—the power high of that.”

It’s no surprise that Beth gets a power high from defeating her male opponents, as it is a very insular boys’ club into which she enters as a dowdily-dressed teenager in the ’50s. For her first match with Beltik at the Kentucky Chess Championship, Melling says, the former is very much in his element, “and then she sort of enters his sphere, and he becomes completely in awe of her talent, and he knows that she’s a better player than him. His bubble gets burst very quick.”

Though Benny saunters into their first match together, Brodie-Sangster acknowledges that there is also an immediate spark with Beth. “Her presence is a bit of a surprise, and a bit of an enigma for him,” he says. “She is very much in a man’s world and doesn’t really look like she really fits in there; neither does he, and I think there’s a kind of connection there.”

Beth grows up in the world of chess, both as an aspiring grandmaster and as a young woman. Taylor-Joy had a blast playing so many different versions of Beth, though she laughs recalling how Frank initially asked her how young she thought she could play. Fourteen or fifteen was her answer—“eight, you’re gonna have to get another actor to do that one”—and so she portrays Beth from her inelegant teenage years through to her mid-twenties.

Over the course of the series, we witness Beths who are alternately brilliant and awkward, shy and sexy, on top of the world and extremely vulnerable. “Because [the show] takes its time and because you do grow with her, you as an audience are allowed insight into why she is the way she is,” Taylor-Joy says. “You see the things that shape her, and you see her grow from it, and you understand why she’s grown in that direction.”

To move between those many phases, she would devise her own backstories for the different Beths: “She starts off walking very clumsily and awkwardly and almost side-to-side, and then I was like, ‘Oh, and this is the first time she’s ever seen an Audrey Hepburn movie’ and she starts wearing the black pants and the turtleneck and starts standing differently, if a boy’s around. And just trying on different personalities, as I think we all do, especially in that age range, and probably into our adult life. It was really fun.”

In contrast to her male opponents and love interests who inhabit the same sphere, the two key women in Beth’s life exist almost entirely outside of the chess world. Fellow orphan Jolene (Moses Ingram) shows her the ropes at the orphanage, much like an older sister, but resentment stretches between them when Beth is adopted and Jolene is left behind.

“It’s all in how they’ve grown up with each other and gotten to know each other,” says the theatrically trained Ingram of her first on-screen role and the difficult emotional history between Beth and Jolene. “I think people that truly love one another certainly get the very best, but also the very worst, of each other. When you can see someone that deeply, you can’t help but be locked in to one another.”

Complicating their relationship is the fact that preteen Jolene is the one who introduces eight-year-old Beth to the tranquilizer pills to which she immediately becomes addicted. “Jolene was just teaching her how to cope in the only way that Jolene has learned how to cope,” Ingram explains, but that simple act irrevocably shapes Beth’s approach to chess for the next decade. Initially used to “even out” the orphans’ disposition (and then later banned for their habit-forming tendencies), the pills help Beth envision a chessboard in the shadows of her bedroom ceiling at night. Taylor-Joy says she would track Beth’s mental and emotional state not just by the different matches, but by how the ghostly chess pieces appear to her: “Sometimes they’re familiar, sometimes they’re very threatening, it all very much depends on where she’s at.”

Unfortunately, where Beth is often at is relying too much on the pills to help her focus during chess games, believing herself unable to triumph when not in her altered state. Her dilemma is complicated by the fact that the tranquilizer pills come back into her life care of her adoptive mother Alma Wheatley (Marielle Heller), who initially comes off as a stereotypical ’50s housewife who can’t function without “Mother’s Little Helper.” (Though the pills go by the fictional name Xanzolam in the series, they seem to be a cousin of Azolam and other benzodiazepines.)

In the past four years, Heller has been best known behind the camera, as the director of such celebrated films as The Diary of a Teenage Girl (for which she also wrote the screenplay), Can You Ever Forgive Me?, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, and What the Constitution Means to Me. While Heller had always referenced her history as an actor as “part of my superpower as a director,” she says that she began to feel like “a fraud” when directing stars like Tom Hanks or Matthew Rhys. “I started to feel like, ‘Do I even remember what that feels like, to be an actor, to be asked to do these things, to be asked to go into these certain emotional places?’”

So when Frank, a long-time friend, invited her to join the series and spend a few months shooting in Berlin, Heller saw it as the perfect opportunity to, in her words, “keep my street cred as a director who was an actor.” As a director who seeks out projects about the uncomfortable things that people don’t talk about, Heller found that Alma embodied those same sensibilities: “She’s someone who has a lot of pain in her past, and that makes her most interesting; she’s not some version of a ’50s housewife that doesn’t feel real. So much of what I try to do as a director is to tap into that thing that has made somebody the way they are.”

Despite mother and daughter’s initial friction, as Beth carves out her niche in the chess world, and Alma begins accompanying her on her more glamorous tournaments, the older woman is inspired to revisit her own long-abandoned dreams of devoting her life to a creative pursuit. “For Alma,” Heller says, “she had this dream deferred. She was somebody who wanted to be a pianist and artist and never could, and that’s a pain that I feel is very human, and I totally connected to.”

What’s remarkable about The Queen’s Gambit is that each of its female characters experiences a different and specific struggle for the time period. “Scott did that really beautifully,” Ingram says of playing adult Jolene, advocating for change during the Civil Rights movement while Beth is moving up through the ranks of the chess world. “He didn’t let us forget what point in time we were in the world—we’re in the ’60s, in the smack-dab [middle] of civil unrest, because people aren’t being treated fairly. And I loved that Jolene is out front and being a crusader, being a champion for change, when very clearly all she’s known is white people her whole life. So it was beautiful to see that she’s found herself later, in changing the world—trying to, at least.”

In that endeavor, Jolene describes herself as a radical, though Ingram also feels that the word was a fitting theme for the series overall.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

“I think it’s radical that Beth, as a woman, is this far into the chess world at this point in time,” she says. “It’s unheard of that she’s there, and everyone’s shocked by it. It’s definitely a story of radical love, and radical faith.”

The Queen’s Gambit premieres October 23 on Netflix.

The post Anya Taylor-Joy Infiltrates the Boys’ Club of Chess in The Queen’s Gambit appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3lT3Wky

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Will Photography Survive Its Art-Historical Karma?

via One Good Eye (Denver)

“I wanted to learn at all costs what Photography was ‘in itself,’ by what essential feature it was to be distinguished from the community of images.” – Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, 1980

Month of Photography is just about over, and again, it was a great set of shows, with a diverse array of aesthetics and concepts. But going around and looking at these shows, I can’t help but skew every single one of them with this train of thought, which was at the forefront of my mind even during the last MoP. What I’m talking about is this funny notion that like, what photography did to painting oh-so-many years ago, it’s now suffering itself next to the infinite scrollability of the internet, and as a fine-art discipline is now sort of scampering in painting’s footsteps, conceptually.

Okay, so what do I mean, exactly?

I remember a few years ago suddenly realizing, with everyone talking about how ISIS was using Instagram as their new principal recruitment vehicle, that this was the same Instagram that was in my pocket. Sure enough, a few copy-pasted arabic hashtags (who knows) later, and I was seeing the frontlines of the mythic War On Terror through the eyes of the enemy. Graphic Stuff. Not something many people would want to see, and yes, I definitely worried about the NSA liking my Facebook statuses in the future, but just pause and think about what I’m getting at here. If you can have an experience that shockingly unique on Instagram, an experience also by most accounts not-at-all-Art, where does that leave Photography, the medium of imagery, in its fine-art gallery context? Where does it find meaning anymore?

Without diving too deep into a conversation that is largely played out, this is just so obvious an echo to me of the art-historic birth of the photograph (among other technological revolutions) planting the modernist seeds of conceptual art in painting. Like, ‘okay, well, if we can’t just be images anymore, what can we be?’ Self-reference begets itself.

Today, it’s likewise the case that photographs in a gallery rarely seem to hold up merely by the merit of their imagery. Some do, sure. But as a whole, how much of the representative body of MoP 2017 were ‘just photos’, vs. how much seemed to raise the question of the taxonomical boundaries of Photography? Coincidence?

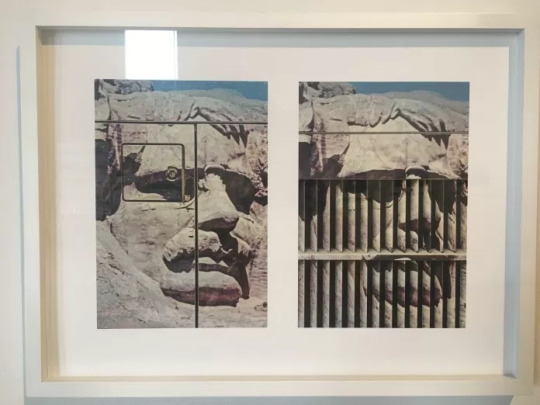

It’s interesting because much of the best work that was ‘purely photographic’ seemed to reference its own flatness (see: the sort of iconic moment of painting’s departure from photography, denying the illusionistic depth of the picture plane and calling attention to itself as an object). Take, for example, Michael Borek’s really wonderful series in the entry alcove of Redline’s Between the Medium, in which various immediately identifiable landmarks suddenly ‘freeze’ flat as you notice that they’re just photos of photos of the landmarks, applied as vinyl to the sides of buses or some other sort of metal industrially-paneled surfaces. These defining, contrasty fissures in the images’ surfaces carve their own space up like a Mondrian, referencing the perpendicular edges of the picture plane. The fact that multiple images wind up in a single frame in this body of work only further adds to the feeling that these things are really about themselves being viewed.

Even further down the line of the ‘Expanded Field’ trajectory of painterly dialogue, another really exceptional body of work belongs to George Perez at Alto’s Denver Collage Club group show. Stacks of home photos with their centers carved out, like tunnels through remembrance of a vacation or something, are curled from being wrapped tightly in rubber bands. They become objects, almost. At least more than they would simply as a stack of images, which would read as a presentation strategy more than a state of being. The tension in their form, though, sort of snaps you out of viewing their content, and all you can pay attention to is the density of them together, in the room. There’s something very real and here-and-now that happens from this – it’s what Rauschenberg was seeking, on a humble scale.

This ‘in the room’ feeling seems to be one of the most prevalent trends for Month of Photography shows this year, in one way or another. At Leon’s Skins, Tya Alisa Anthony sheds the frames from her images, letting the prints ripple in the air conditioning, the texture of the images breathing the same air as us, getting us all the closer to the skin of her models, the face-value subject of the show.

A similar sort of relationship-to-the-body occurs in the best pieces at CVA’s Presence: Reflections on the Middle East, a series in which the ornately decorated windshields and interiors of various public transit buses fill the frame, life-sized, allowing us to sort of sit directly in front of these things, contemplating them as stand-in portraits of who might be driving them. You feel empathy for the ghost of the driver purely for the sake that you could almost step in there. Tableau-vivants.

I mean, I’ll admit, I’m definitely putting a spin on all of this, framing all this work this way. I’m biased, I’m a painter. But let’s take a step back from the as-painting conversation, and talk about MCA’s Ryan McGinley retro. Here is an utterly ‘just photo’ show, and what’s more, it’s totally the kind of thing that you would see on the internet. But where the show is interesting is that it’s there in physical space with you. It’s the fact that an art museum is willing to put blowjobs, pissing, coke-sniffing, and projectile-vomiting on their walls, larger than life. The difference between a computer screen and an art museum was really driven home here when a circa-eight-year-old girl ran ahead of her parents into the porniest room of the exhibition as I was leaving.

The most successful show this past month, in my opinion, was David B Smith’s Penelope Umbrico solo, because it really brought all of the things I’ve mentioned together in a dialogue that felt very nuanced and high-level. At first glance, it’s certainly the most painterly show, with large, manipulated images in various forms of prints and frames, repetitiously referencing fluorescence in various ways. As well as themselves, rather explicitly. But from the serial, tiled arrangements, even overlapping, of the photos, to the most resonant moments – rows of polaroids of lens flares and fireworks, hung just high enough so that the track lighting reflects into your eyes, the show is about the entire thing together, there, in the room. Which is why the way that these polaroids, sparklingly activated by their surroundings, are so much more interesting than the superficially similar arrangement of McGinley’s at MCA. When I asked a gallery attendant if Umbrico always made photography, I got the response that photography was her subject, not necessarily her medium. Nice.

Plenty of these shows had politically or otherwise relevant content, but let’s face it, none of them really dug into anything in a way more significant than what you’d get from a few seconds of googling their themes on your phone. There’s plenty to say about various work that was successful that I didn’t touch on, as well, sure. But at the end of the day, the only work that really felt like it was alive and thriving and not just there because it’s the biennial was the work that was aware of itself. Maybe aware of its own mortality. Which is where I go back to my original point — that the ‘aura’, the ineffable thing that was supposedly the last stand of painting in the face of photography, may be all that photography has left to set its fine-art status aside from the unending stream of images we see every day.

“Even the most perfect reproduction … is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” –Walter Benjamin, Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, 1936

2 notes

·

View notes