#the death of good duke humphrey

Text

Where no manuscripts are extant, matters are less easily resolved, as is illustrated by the late-fourteenth-century library of Eleanor de Bohun. An important part of the directions making up Eleanor's testament relates to books, as she took pains to distribute them amongst her children in a way which would be appropriate for their respective callings in life. To her daughter, Isabella, a minoress, for instance, she bequeathed a French bible and book of decretals, a book of lives of the fathers, 'les pastorelx Seint Gregoire', and other devotional books. To her son Humphrey, on the other hand, she left texts which centred on chivalry and the active life: a chronicle of France, Giles of Rome's De regimine principum, a book of vices and virtues, the Bohun ancestral romance of the 'chivaler a cigne', and a richly illuminated psalter which had belonged to her father, and which she wished to remain in the family line, passing from heir to heir. She is known to have commissioned, on her own account, the Edinburgh Psalter, National Library of Scotland Advocates' MS 18.6.5. Her concerns are quite consistent with those displayed by other members of her family, in particular her father, and her younger sister, Mary, both of whom were active as patrons. Now Eleanor was married to Thomas, duke of Gloucester, whose death in 1397 occasioned the compilation of an inventory of goods which is justly famous for its collection of books. Yet few historians have acknowledged the role which Eleanor may have had to play in the establishing and augmenting of this library, in spite of her proven interest.

Carol M. Meale, "'. . . alle the bokes that I haue of latyn, englisch, and frensch': lay women and their books in late medieval England', Women and literature in Britain, 1150-1500 (Cambridge University Press, 1996)

#eleanor de bohun#thomas of woodstock#patronage#mary de bohun#humphrey de bohun 7th earl of hereford#historian: carol m. meale#bohun manuscripts

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE OLD ENGLISH BARON: A GOTHIC STORY.

In the minority of Henry the Sixth, King of England, when the renowned John, Duke of Bedford was Regent of France, and Humphrey, the good Duke of Gloucester, was Protector of England, a worthy knight, called Sir Philip Harclay, returned from his travels to England, his native country. He had served under the glorious King Henry the Fifth with distinguished valour, had acquired an honourable fame, and was no less esteemed for Christian virtues than for deeds of chivalry. After the death of his prince, he entered into the service of the Greek emperor, and distinguished his courage against the encroachments of the Saracens. In a battle there, he took prisoner a certain gentleman, by name M. Zadisky, of Greek extraction, but brought up by a Saracen officer; this man he converted to the Christian faith; after which he bound him to himself by the ties of friendship and gratitude, and he resolved to continue with his benefactor. After thirty years travel and warlike service, he determined to return to his native land, and to spend the remainder of his life in peace; and, by devoting himself to works of piety and charity, prepare for a better state hereafter.

0 notes

Note

Hi, I have a question about Henry V if thats ok?How reliable are reports about Henrys “wild youth” ? Are there any contemporary sources for it or is it a latter invention?

Hi, that is definitely more than OK! I love getting questions about my boy.

There are contemporary sources for Henry's wild youth. The earliest version of the "great change" from the riotous prince to dignified king is found Thomas Walsingham’s chronicle:

as soon as he was invested with the emblems of royalty, he suddenly became a different man. His care now was for self-restraint and goodness and gravity, and there was no kind of virtue which he put on one side and did not desire to practise himself. [1]

However, as much as I love him, Shakespeare's "madcap prince" Hal as depicted in Henry IV, Parts One and Two, has very little in common with the historical Henry. The story of his criminal tendencies and arrest by Chief Justice Gascoigne are 16th century inventions. Most of his Eastcheap associates are characters invented by Shakespeare - there was no historical counterparts for Poins, Mistress Quickly, Doll Tearsheet, Bardolph and Peto, and the historical counterparts for Falstaff (Sir John Oldcastle, Sir John Fastolf) have little in common with him.

So what did the historical Henry's wildness look like? The anonymous Vita et Gesta Henrici Quinti tells us Henry was:

an assiduous pursuer of fun, devoted to organ instruments [an intentional double entendre] which relaxed the rein on his modesty, although under the military service of Mars, he seethed youthfully with the flames of Venus too, and tended to be open to other novelties as befitted the age of his untamed youth. [2]

The Vita et Gesta had been commissioned by Walter, Lord Hungerford who was close to Henry (reportedly, Hungerford held him in his arms as he died) and similar sentiments are found in Tito Livio Frulovisi's Vita Henrici Quinti, commissioned by Henry's youngest brother, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester:

He delighted in song and musical instruments, he exercised meanly the feats of Venus and of Mars, and other pastimes of youth for so long as the King his father lived. [3]

Both of these texts were written in the mid-to-late 1430s after Henry's death and this, alongside with their sources, suggests that they should be taken seriously. Basically, they seem to be saying that he was young, he liked fun, he liked music, he liked sex and while he may have worked hard, he partied hard too.

Some of these claims are verifiable. We know Henry liked music, we know he played the harp, recorder and pipes/flutes and that he may have been the "Roy Henry" who composed two mass movements found in the Old Hall Manuscript collection, though the Vita et Gesta probably didn’t mean that kind of music. We know that much of Henry's adolescence was spent dealing with Owain Glyndŵr's revolt and that at sixteen, he fought at the Battle of Shrewsbury and was seriously wounded.

The claims that Henry "seethed youthfully with the flames of Venus" are more difficult to substantiate. There is no evidence Henry had mistresses or illegitimate children though it’s possible, even likely, that such evidence wouldn’t survive, particularly if he had no long term sexual relationships. Nor were there rumours that he engaged in relationships with favourites that were "not without some taint of an obscene relationship", to quote Walsingham on Richard II’s relationship with Robert de Vere [1]. One of Henry’s close friends, Richard Courtenay, Bishop of Norwich, apparently commented that he did not believe "that [Henry] had known women carnally after having received the crown" [4], which might, as some historians suggest, imply that this celibacy was notable in comparison to what came before. It also might be notable that Courtenay has been suggested to have been Henry’s lover. So the image of Henry as a playboy prince is more difficult to prove but not impossible.

The story that Henry banished his unsuitable companions upon his coronation first appears in an anonymous version of The Brut, written in 1478-1479. Gwilym Dodd attempted to find evidence of this story in contemporary records such as charter witnesses, household appointments and the coronation livery roll, and there is no evidence of a great purge of Henry’s household. He did distance himself from the “infamous heretic”, Sir John Oldcastle, and fourteen lower status men who had been retained for life by Henry when Prince of Wales did not appear to have been taken on by him as king. But “there is no other evidence to suggest that he turned his back on his former associates“. The story he did might simply reflect “the inevitable transformation of [...] the relatively small, exclusive ‘private’ affinity of a Prince into a much enlarged and inclusive 'public' affinity of a king” [5].

With all this caveats about Henry V’s “wildness” it might be worth noting that Dodd suggests the story of Henry’s household purge might be to allow the author to acknowledge some of the less... salubrious aspects of Henry’s behaviour as prince without blaming Henry himself but on the nameless unsuitable companions who had already been appropriately “dealt with” by Henry. James C. Bulman, editor of the Arden Henry IV, Part Two, also offers the possible solution that the “wild youth” might have disguised the more serious conflicts between Henry and his father.

In the last years of Henry IV’s reign, Henry was often in serious conflict with his father. This “wildness” might have been a way of talking about this conflict without acknowledging the often treasonous undertones and undercurrents of both patricide and filicide. The image we have of Henry in the last years of Henry IV’s reign is of, as Katherine J. Lewis puts it, “an ambitious young man refusing to wait his turn for power within the the patriarchal hierarchy patiently and submissively” [6]. There were rumours that he or Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester had urged Henry IV to abdicate in his favour, something that was hardly going to go down well with the king. There were also rumours that Henry had been plotting to usurp his father which Henry felt he had to strenuously denied and allegations of misconduct that he was eventually cleared of. On his part, Henry IV was rumoured to be considering disinheriting Prince Henry to allow the crown to pass to his second and favourite son, Thomas, Duke of Clarence, and may have been playing his sons off each other to maintain control of them. The First English Life of Henry the Fifth, written in 1513, contains a story where Prince Henry sought to reconcile with his father and, granted an audience with him, gave his father a knife and told him "I desire you in your honour of God, for the easing of your heart, here before your knees to slay me with this dagger" [7]. The fact that the First English Life was written 100 years after Henry IV’s death and it’s source for this story is unknown may make this story doubtful but it does speak to the tensions around Henry’s relationship with his father. In addition to the possibility that the “wild prince” story was a way of acknowledging this conflict indirectly, two of Henry’s biographers, Teresa Cole and John Matusiak, both speculated that Henry’s wayward behaviour might have been come as a reaction to this conflict.

Henry also clashed with some of the “old guard” of his father’s regime, most notably Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury and possibly William Gascoigne, the Chief Justice of England in Henry IV’s reign, who was either removed from office or resigned shortly after Henry V’s accession. Peter McNiven in also makes a convincing case for Prince Henry having some sympathies with or at least tolerance for Lollardy, which might made him an alarming prospect for those, such as Henry IV and Archbishop Arundel, who supported a hardline approach the “Lollard problem” (the second year of Henry IV’s reign saw the passing of De heretico comburendo, a law which punished heresy by burning at the stake; it is largely viewed to be Arundel’s pet project). It might be that Henry V’s wildness might have been, to build on Bulman’s suggestion, a way to disguise less acceptable and more controversial positions Henry might have held.

Personally, yes, I think that the idea of the “wild youth” might be to disguise the more serious conflicts going on at the centre of power and in some ways makes for a “sexier” story than political conflicts. I also think that if there is truth to the “worked hard, partied hard” image, this may have come as a reaction to the situation Henry found himself in. Henry had come to adulthood in the midst of immense pressures, from civil war, rebellion and conflict with his father and brother. He turned thirteen in the middle of his father’s usurpation of the throne and the deposition of Richard II - someone Henry seems to have been fond of. A handful of months after Henry’s thirteenth birthday, he survived the Epiphany Rising, a plot to restore Richard II to the throne and to kill his father - and, allegedly, to kill himself and his three younger brothers. He was just sixteen years old at the Battle of Shrewsbury, one of the bloodiest battles fought on English soil. He was severely injured, taking an arrow to the face, and left permanently disfigured - no doubt a traumatic experience. It would be hardly surprising if he sought outlets for these stresses and trauma in sex, alcohol and other wayward behaviour.

----

[1] The Chronica Maiora of Thomas Walsingham, trans. David Preest (The Boydell Press 2005)

[2] Anne Curry, Henry V: From Playboy Prince to Warrior King (Penguin Monarchs 2015), annotations as in text.

[3] my modernisation of "He delighted in songe and musicall Instruments, he exercised meanelie the feates of Venus; and of Mars, and other pastimes of youth, for so longe as the Kinge his father liued" from C.L. Kingsford, ed., The First English Life of Henry V (Clarendon Press 1911)). The First English Life is largely a translation of Frulovisi's Vita and the only English translation.

[4] original Latin: "non credebat quod cognovisset mulierem carnaliter post quam ipse coronam susceperat”

[5] “Henry V’s Establishment: Service, Loyalty and Reward in 1413“ in Henry V: New Interpretations, ed. Gwilym Dodd (York Medieval Press 2018). All quotes in this paragraph come from here.

[6] Kingship and Masculinity in Late Medieval England (Routledge 2013)

[7] A. R. Myers, ed. English Historical Documents: 1327-1485 (Routledge 1969), modernised from C.L. Kingsford, ed., The First English Life of Henry V (Clarendon Press 1911)).

Other sources mentioned:

Cole, Teresa, Henry V: The Life of the Warrior King & the Battle of Agincourt (Amberley 2016)

Matusiak, John, Henry V (Routledge 2013)

McNiven, Peter, Heresy and Politics in the Reign of Henry IV: The Burning of John Badby (The Boydell Press 1987)

Shakespeare, William, King Henry IV, Part 2, ed. James C. Bulman (Bloomsbury 2016)

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did Margaret's father really kill himself? Would she have known about it, it would her mother have covered it up to protect her?

[content warning for discussions of suicide]

Hi, anon! I'm sorry, I received this ask some two months ago but it got buried in my inbox. All we know about John Beaufort (Margaret's father)'s death is that it happened suddenly. He had just come back from a campaign in France where he had performed less than nobly by committing war crimes against civilians, squandering the crown's funds to advance his own interests and even bizarrely attacking one of England's allies against France (Brittany). His actions deeply angered Henry VI; according to a contemporary chronicle (Ingulf's Chronicle), the Duke of Somerset was summoned to court upon his return and ‘being accused of treason there, was forbidden to appear in the king’s presence’. Disgraced, John Beaufort withdrew to his Dorset estates, and on the 27th of May 1444:

The noble heart of a man of such high rank upon hearing this most unhappy news, was moved to extreme indignation; and being unable to bear the stain of so great a disgrace, he accelerated his death by putting an end to his existence, it is generally said; preferring thus to cut short his sorrow, rather than pass a life of misery, labouring under so disgraceful a charge.

The Croyland Chronicle is the only chronicle to suggest John Beaufort died by suicide. Other chroniclers simply said John Beaufort died suddenly. Interestingly, Henry VI's uncle, Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, would also die suddenly after being accused of treason and denied access to the king, but suicide was ruled out in his case — admittedly, Humphrey died whilst in the king's custody when John Beaufort did not, but there might be another explanation for the suicide allegations. The Croyland Chronicler was not exactly a fan of the Duke of Somerset. John Beaufort owned lands near the abbey, and the chronicler complained that ‘tolls were levied by his servants in the vills’ while ‘all the cattle were driven away’. There was a dispute between Croyland's Abbot and John Beaufort because the latter had declared that the abbey's monks were forbidden from using the embankment he had built to transport goods to and from the abbey. The Abbot protested to King Henry VI, which apparently only displeased the duke further. The result of their dispute is unknown.

It might be that the Croyland Chronicler was unhappy enough about John Beaufort to repeat the suicide rumour, but I wouldn't say the chronicler was the one who created it. Whatever the case, it's hard to believe in suicide considering Beaufort died intestate (without a will) and he had gone to extreme lengths before his French campaign to make sure his daughter (Margaret) would be well-provided for in the case of his death and his illegitimate daughter Tacine would be made an English citizen in his absence. In that regard, he seems to have been a careful man, but on the contrary, perhaps he deemed this earlier arrangement all that was sufficient for his children. His wife was pregnant again at the time, and we don't know if she miscarried upon his death or if the baby died very young but it wasn't talked about again.

Who can tell? Suicide is not always logical or follows a logical order of events. John Beaufort was the English nobleman who spent the longest time in captivity in France during the Hundred Years' War: he spent no less than 17 years as a prisoner from the time he was a teenager captured at the Battle of Baugé to the time he was ransomed for an astronomical sum that left him impoverished. I imagine that kind of situation must leave deep psychological scars. However, it should also be said that John's father had died around the same age John died (40), not as suddenly, but still, even younger (37-38). John Beaufort had taken a long time to depart to France and whilst that might be because he was expecting the birth of his daughter Margaret, it might be that he had been ill too. Being in the king's bad books might have added additional stress to his earlier condition.

Would Margaret have known about her father's alleged suicide? I don't know! Croyland was the only chronicle to mention it but he also claimed that the rumour was 'generally said' at the time of the duke's death. It might be that Margaret heard about it at some point as she grew up. She was evidently interested enough in her father's soul to order prayers for him at Cambridge and at Wimborne where she ordered a double tomb for him and her mother. The fact that she ordered prayers for his soul though doesn't tell us much because it was an established custom to order prayers for one's parents.

Considering no other chronicle repeated the rumours, I would say they had died by the time Henry VII became king. I'd imagine Richard III would also have used it against Henry at the time of his smear campaign if the rumour was still circulating by 1485. If Margaret ever heard about her father's alleged suicide, I imagine it would have been during her childhood and not later on. Would her mother have told her about it? Would the servants have gossiped about that? Now, that's some speculation that historical fiction could explore better.

Thanks for the ask! 🌹x

#ask#anon#margaret beaufort#john beaufort 1st duke of somerset#tw: suicide#suicide mention /#suicide mention tw

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE PRETTY RECKLESS Shares Acoustic Version Of 'Harley Darling' From 'Other Worlds' Collection

THE PRETTY RECKLESS will release a new collection of music, "Other Worlds", on November 4 via Fearless Records. The effort sees the group delivering its first proper acoustic recordings, unexpected covers and other reimaginings.

Today, the band has shared the visualizer for the acoustic version of "Harley Darling". Watch it below.

THE PRETTY RECKLESS dressed down this favorite from the band's latest album, "Death By Rock And Roll", to its bare essence with a stirring and striking acoustic performance.

"'Harley Darling' is a love letter to [late THE PRETTY RECKLESS producer] Kato Khandwala," says singer Taylor Momsen. "It's as simple as that. So many of us have stories of losing loved ones, especially now, and I hope this song can be used in other's healing as it was in my own."

"Other Worlds" collates striking acoustic renditions of personal favorites accompanied by some very special guests. The recording of Elvis Costello's "(What's So Funny 'Bout) Peace, Love And Understanding" served as Momsen's first cover originally performed for the "Fearless At Home" livestream in the midst of COVID. As another pandemic-era cover, Matt Cameron played guitar and sang as Taylor powered an airy and lithe reimagining of SOUNDGARDEN's "Halfway There" from "King Animal", generating hundreds of thousands of views on its initial post. Iconic multi-instrumentalist, producer and artist Alain Johannes handled guitar on THE PRETTY RECKLESS' pensive and poetic interpretation of "The Keeper", originally by Chris Cornell, while David Bowie pianist Mike Garson performed a stirring piano movement for THE THIN WHITE DUKE's "Quicksand".

"For a long time, we've been trying to figure out an alternative way of releasing music, including songs we love that didn't make our records, covers, and alternate versions," explains Momsen. "We found a way to do this coherently and consistently with 'Other Worlds'. We're a rock band, so there are lots of electric guitars on our records. However, we've gotten incredible feedback from fans about our acoustic performances, and we'd never put those out in any real format. So, this is a different take on the traditional format of a record and a stripped back version of us that our fans haven't really heard before, but it's still us."

"You get to hear a different side of Taylor's vocals," adds guitarist Ben Phillips. "It was a chance for us to see what she would sound like singing songs by people who have inspired us. It also gave us some perspective of where we need to go and what we need to be if we want to be that good."

"Other Worlds" track listing:

01. Got So High (remix)

02. Loud Love

03. The Keeper (feat. Alain Johannes)

04. Quicksand (feat. Mike Garson)

05. 25 (acoustic)

06. Only Love Can Save Me Now (acoustic)

07. Death By Rock And Roll (acoustic)

08. Halfway There (feat. Matt Cameron)

09. (What's So Funny 'Bout) Peace, Love And Understanding

10. Harley Darling (acoustic)

11. Got So High (album version)

"Death By Rock And Roll" was made available in February 2021 via Fearless Records in the U.S. and Century Media Records in the rest of the world.

Upon release, "Death By Rock And Roll" topped multiple sales charts — including Billboard's Top Albums, Rock, Hard Music, and Digital charts. The record also yielded three back-to-back No. 1 singles — "Death By Rock And Roll", "And So It Went" (featuring Tom Morello of RAGE AGAINST THE MACHINE) and "Only Love Can Save Me Now" (featuring Kim Thayil and Matt Cameron of SOUNDGARDEN). The band has tallied seven No. 1 singles at the rock format throughout its career.

"Death By Rock And Roll" is THE PRETTY RECKLESS's first album to be made without longtime producer Kato Khandwala, who died in April 2018 from injuries sustained in a motorcycle accident.

THE PRETTY RECKLESS formed in 2009 and is rounded out by bassist Mark Damon and drummer Jamie Perkins.

Last year, Momsen — who rose to fame portraying the character of edgy little sister Jenny Humphrey on The CW's "Gossip Girl" — described "Death By Rock And Roll" in an interview with ABC Audio as a "battle cry for life and for hope."

"I think that that's something that we can all use a little bit more of, especially right now," she said. "We could always use a little more hope, and we could always use a little more rock and roll."

youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journey to Bosworth, conclusion. Why did Richard III lose?

Before starting, I have to say that this is my personal opinion. For me, this is why the last Plantagenet king falled. As you will see, I do not consider that it was the most probable outcome, far from it.

At Bosworth, Richard III lost while he had more men, more support and was an experienced commander with experienced lieutenants

Many argued that he lost because he was sold out by the magnates. After all, Northumberland and Lord Stanley didn't move to help him, and Sir William Stanley 'betrayed' him.

This explanation is helpful but reductive and simplistic. Betrayal was very common in the War of the Roses. Richard III had witnessed it all his life. In 1459, while Richard was seven years old, his father fled to Ireland because one of his lieutenants had defected to Henry VI. He saw his father's castle in Ludlow be stormed out by Lancastrians. Richard III also saw his closest ally, the duke of Buckingham, turn on him for little reason in 1483. He was used to it.

Stanley and Northumberland's defection was utterly predictable Richard III knew that Northumberland intentionally brought as little troops as he could and Richard put so little faith toward lord Stanley that he took hostage his heir (a maneuver which did work at buying his neutrality).

As for Sir William Stanley's decisive defection, it wasn't even a surprise. Richard III branded him a traitor a few weeks before. He acted accordingly.

Nor did Richard III lacked information about his enemies. Henry Tudor was openly his rival since the beginning of his reign. His chief commander, John de Vere, was known from Richard. He fought against him at Barnet, stole his lands, and tried to have him executed in 1484. He also knew that the french disliked him as well as he disliked them. Their investment in the Tudor cause is hardly surprising.

To sum it up: there was little asymmetry of information between Richard III and his rivals. Richard knew his friends, knew who wasn't reliable, and knew his enemies. True, he didn't know some key information such as where would Henry Tudor would land, just as some minor defections came out as a bitter surprise. Seeing Rhys ap Thomas defect to the Tudors after he pensioned him 10 marks a year was an unwelcome surprise, but hardly a fatal one.

Few contemporaries thought that Henry Tudor would actually win (partly because they didn't know the intentions of some key magnates). There are many examples of that. In 1484, Queen Elizabeth Woodville accepted to quit her sanctuary and made peace with her (alleged) brother-in-law in exchange for a correct treatment of her daughters. She did hand some of her daughters to him. Her brother Richard Woodville did make his peace with Richard III, and her son the Marquess of Dorset also attempted to run from France to make his personal peace before being stopped by the Tudors.

Pierre Landais tried to sold-out Henry Tudor to Richard III in 1484, showing how little faith he had in a Tudor victory. After Henry landed and marched from Wales toward England, the city of Swhresbury obstinately refused to let him pass, fearing Richard's wrath (and possible lawlessness). Only Sir William Stanley's intervention would convince them.

In no way Henry Tudor had massive support. From his landing to the battle of Bosworth, defections to his side were few. Rhys ap Thomas, Sir John Savage, Sir Gilbert Talbot, and lesser noteworthy welsh were all local figures. Compared to the 1483 rebellion (ill-named Buckingham's rebellion) in which three different areas revolted with some major rebellious figures such as the duke of Buckingham, Sir Thomas Saint-Leger, and the Wydevilles, the defections during the invasion look marginal. Especially when one considers that Henry Tudor landed in Wales because he thought he had support there, and conversely Richard III had little.

Henry Tudor had little chance of winning. He tried because no compromise was possible with Richard III, who showed often his ruthlessness. Most of the surviving rebels in 1483 had joined Henry in exile and pressed him to act. Their lands were already forfeited and distributed to Richard's supporters, and only Richard's death could vindicate and restore their wealth completely. As Henry Tudor knew in the Britton court, foreign support to English pretenders was erratic and highly conjunctural at best. The Brittons supported him in 1483, and a court faction attempted to sell him out the very next year. So, when France proposed limited financial and military support during the summer of 1485, he couldn't hesitate. It was his best shot.

Richard III on the reverse had real reasons to quiet himself and be confident in his victory. Why he most certainly wasn't might be due to private reasons. His wife and son died during his brief reign. This might have awakened a sense of insecurity. At its core, Richard might have felt insecure about his legitimacy. He had parliamentary approval of his regal title with Titus Regulus, he had been sacred and anointed but was he legitimate? The allegation of bastardy toward his nephews was based on oral claims, which was weak evidence at best.

The best proof of his legitimacy, and that God approved his reign was a battle. A winning battle would re-assert his reputation as a martial ruler, and more importantly, showed that God favored his claim in an ordeal by combat. In a martial, zealously religious society, a battle would be the final seal of his legitimacy, just as his brother, who reasserted his claim during numerous victorious battles. This was a fitting narrative for him. He was one of the best English military commanders alive, with an undeniably good military record. He could surely win against a nobody with no military experience. His spiteful royal denunciation of Henry Tudor in 1484 might be evidence that Richard III viewed the Tudor challenge as highly personal. Henry itself was the threat, more than those that supported him or were propping him up.

During Buckingham's rebellion, Richard III didn't fight despite rushing to the south where the rebels were. The Howards and Sir Humphrey Stafford put down the rebellion without him. And Henry Tudor could flee.

So Richard III had a practical and a theological/theoretical reason to force combat between his and the Tudor. Reasserting and confirming his legitimacy was one, and making sure that Henry Tudor would cause no more trouble was the other.

A decay in mental health is also possible from Richard III. He was a man who was highly confident in his skills and his worth. However, the atmosphere of betrayal and the loss of his family in the last few years did pull a tool on him. His legendary 'bad dream' on the eve of Bosworth was the most remarkable example of that.

So when the rebel army did come in England, Richard III rushed toward them. He had reinforcement still coming on the day of the battle. York men were on their way and more forces certainly were coming from elsewhere. Time was on his side. He rushed toward the enemy perhaps because, in a spike of paranoia, he didn't want more defections and more betrayal, or because he wanted to put an end to it. What if the rebels fled at the sight of his numerically larger army, like his father at Ludlow? He didn't want that, he didn't want to endure a decade-long pretender like Edward IV would endure with Henry VI or Henry Tudor with 'Richard' (Perkin Warbeck)

When Northumberland refused to support Howard against Oxford, it didn't matter for Richard III. He knew Northumberland's opportunism. Catesby proposed to retreat like his father at Ludlow, like his brother when key magnates turned on him in 1470. He refused. Richard III simply couldn't admit his defeat on the battlefield, even as a temporary setback. His desire for legitimacy, his pride forbid it. He told so to Diego de Valera, the Spanish Ambassador, who reported it to his masters about the battle: "Now when Salazar, your little vassal, who was there in King Richard's service, saw the treason of the king's people, he went up to him and said: 'Sire, take steps to put your person in safety without expecting to have the victory in today's battle, owing to the manifest treason in your following.' But the King replied: 'Salazar, God forbid I yield one step. This day I will die as King or win'. "

At the battle, he wanted personal physical contact. He wanted to perform the deed of a knight, personally slain the Tudor dragon. He was a proud man of action, and couldn't let Howard once again defeat the core of the rebels while he was on the fence. Hence his fateful charge. This decision, more than any other, was fatal.

Richard III wanted Bosworth, Richard III made Bosworth. He accepted every odds. He accepted the disloyalty of Northumberland instead of assuming its consequences and retreat to reorganize. He ignored Sir William Stanley on his rear when he charged because he wanted to stick to his narrative. He was supremely confident in his skills and his capacity to slain Henry Tudor before Stanley could destroy him. And he was too insecure and proud to run. Run would be admitting his illegitimacy.

In other words, Richard III never admitted retreat as an option. Richard III also desperately wanted personal challenges. It is no coincidence that the last Plantagenet was both the last English king to die in battle and the only one to do so since the dawn of the Norman era.

When Richard III, in his last instants, shout 'treason' it was partly because Sir William Stanley's betrayal was relatively fresh in his mind, and to him, it was an English subject killing their king. It might have also been a way to cope. He was losing, he couldn't perform his martial ability in a winning way. Putting his failure on betrayal and a rigged battle was simply a way to cope

In conclusion, Richard III consciously and unconsciously shut down options that didn't fit his preferred narrative. This dysfunctional decision-making was partly created from his personal identity and value, and partly due to his society's views. This makes us understand why he chooses options that didn't favor his self-preservation and why he didn't retreat or acted differently. And it destroyed him.

#richard iii#henry vii of england#battle of bosworth#why henry vii won#And learned a lesson#we have no evidence of Henry VII putting himself in danger more than necessary during the many challenges of his reign

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

POCKET BLOGS: Saye Anything

Hey everyone! Mya here. I’m really excited today to introduce a new feature here on Good Tickle Brain: POCKET BLOGS! As regular readers will know, since 2019 I have been working on my comics with the world’s first, foremost, and possibly only pocket dramaturg, Kate Pitt. (For more on Kate, including the etymology of the term “pocket dramaturg”, check out this Q&A with her.)

Kate is, if anything, an even bigger Shakespeare geek than me, and certainly has a bigger Shakespeare brain. I will often text her a random Shakespeare fact and say “Isn’t this cool?”, only to receive back “YES, and…” followed by a dozen more related facts, complete with footnotes. As I am taking the month off, I thought it only fair to share some of her delightful geekery and expertise with all of you.

So sit back and get ready to peer into some of the most geeky, random, and entertaining corners of the Shakespeare-verse with Good Tickle Brain’s new series of POCKET BLOGS!

Spare a thought for poor Lord Saye. The ill-fated lord’s entrance in Henry VI Part II is often overlooked because he arrives at the same time as Queen Margaret. Margaret makes consistently dramatic entrances across the four Shakespeare plays she appears in and there is an excellent chance that someone is about to be stabbed, slapped, or screamed at if she is nearby.

In this scene, Margaret enters carrying the severed head of her very dead ex-lover the Duke of Suffolk, and talks affectionately to it while her husband King Henry desperately tries to work out how to put down a major rebellion.

Saye is in the middle of all this and spends most of his first scene (and he’s only got two) standing around awkwardly while the King and Queen talk to everyone who isn’t him. It can’t feel great to be ignored in favor of someone who is missing his trunk and all of his limbs, and when King Henry finally turns towards Saye it is to point out that the advancing rebels would very much like to turn his head into a tote bag just like Suffolk’s.

Cue the awkward laughter and a messenger running in with the news that the rebels have arrived and everyone present who still has their heels should immediately betake themselves to them and get out of town. King Henry reminds Lord Saye that everyone hates him (because he raised taxes and can speak French) and he should probably join the bravely-running-away royals.

Lord Saye however, declares that he will stay and face the rebels. He is innocent after all. Why should he flee when he has done nothing wrong? At this point, practiced Shakespearean audiences will be reaching for the popcorn. Declaring innocence never ever (ever) works when attempting to avoid unpleasant consequences in Shakespeare and indeed, Lord Saye is captured less than forty lines later and dragged before the rebels to be interrogated.

Jack Cade, the leader of the rebellion, accuses Saye of such abominable crimes as printing, teaching grammar to children, and dressing his horse in excessively fancy horse-clothes. Saye is definitely not guilty of the first indictment, as this scene takes place in 1450 and the first books in England weren’t printed until at least twenty-five years later.

Regardless, the rebels continue to hurl increasingly ridiculous accusations at Lord Saye – “thou hast men about thee that usually talk of a noun and a verb” – while he confidently bats them aside by speaking Latin and quoting Caesar’s Commentaries. Not necessarily the best strategy when negotiating with angry men with pikes, but Saye also demonstrates that he can speak eloquently in plain English:

Tell me, wherein have I offended most?

Have I affected wealth or honor? Speak.

Are my chests filled up with extorted gold?

Is my apparel sumptuous to behold?

Whom have I injured, that you seek my death?

These hands are free from guiltless blood-shedding,

This breast from harboring foul deceitful thoughts.

O, let me live!

Lord Saye’s contention that his hands are “free from guiltless blood-shedding” is equivocal, given that he menacingly indicates elsewhere that he has definitely shed some blood: “Great men have reaching hands. Oft have I struck those that I never saw, and struck them dead.” There were rumors that Saye was involved in the murder of Henry VI’s uncle Duke Humphrey, though Shakespeare depicts that death as definitely Suffolk’s fault.

In addition to being a cunning politician and a huge classics nerd, Lord Saye is also a war hero. Jack Cade contemptuously challenges him, “when struck’st thou one blow in the field?” but Saye fought with Henry V in France. He is now in his mid-fifties and past his fighting days (the rebels mock his palsy) but Lord Saye feels that his prior service to his country should save his life.

Cade disagrees. Even though he admits, “I feel remorse in myself with his words”, he orders Saye to be dragged offstage and beheaded. The rebels also break into Saye’s son-in-law’s house and behead him too. They then put both their heads on pikes and parade around London smushing the heads together to make them look like they are kissing because the rebels are apparently twelve.

Lord Saye is one in a long line of Shakespeare characters who appear briefly and die quickly. Cinna the Poet in Caesar, Young Seward and The Family Macduff in Macbeth, Cornwall’s servant in Lear: all of their deaths, like Saye’s, serve to make the bad guys look worse. However, Jack Cade and his crew have already murdered innocent people before Saye comes on the scene, so what does his death teach the audience that they don’t already know? Dramatically, there may be an argument for cutting this scene. Next week however, I’ll explain the extravagantly silly reasons why I am delighted by Lord Saye and think he should be in every production. (Hint: he’s related to Shakespeare!)

by Kate Pitt

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

round up // NOVEMBER 20

Hi, I’m tired. Actually, my friend Celeste created a piece of art that puts the emphasis needed on that sentiment:

I’m very tired. November felt like it was three years and also felt like it went by in a blink and also I’m not sure where October ended and November began—how does time work like that? (I’ve yet to see Tenet, but maybe that will explain it.) But like Michael Scott, somehow I manage, and lately it’s been like this:

Late-night Etsy scrolling. Browsing beautiful, non-big-box-store artwork is very calming just before I go to bed. I’d recommend Etsy stores like Celeste’s chr paperie shop, which I know from experience is full of great Christmas gift ideas.

Taking a day off of work to do laundry. I’m not sure if it’s more #adulting that I did that or that I was excited to do that.

Eating Ghiradelli chocolate chips straight from the bag. I actually don’t recommend this as a healthy option, but this is also not a health blog.

Watching lots and lots of ‘80s movies. One day I’ll ask a therapist why this decade of films is so comforting for me despite its many flaws, but for now I’m just rolling with it.

Reading. Have you heard of this? It’s a form of entertainment but doesn’t require screens—wild!

Memes. All good Pippin “Fool of a” Took jokes are welcome here.

Leaning into the Christmas spirit by ordering that Starbucks peppermint mocha, making plans to watch everything in that TCM Christmas book I haven’t seen, and keeping the lights on my hot pink tinsel tree on all day as I work from home.

This month’s Round Up is full of stuff that made me smile and stuff that sucked me into its world—I think they’ll do the same for you, too.

November Crowd-Pleasers

Sister Act (1992)

If in four years you aren’t in an emotional state to watch election results roll in, I recommend watching Whoopi Goldberg pretend to be a nun for 100 minutes. (Though, incidentally, if you want to watch that clip edited to specifically depict how the results came in this year, you’ll need to watch Sister Act 2.) This musical-comedy is about as feel-good as it gets, meaning there’s no reason you should wait four more years to watch it. Crowd: 9/10 // Critic: 7.5/10

Nevada Memes

Speaking of election results, Nevada memes. That’s it—that’s the tweet. Vulture has a round up of some of the best.

youtube

SNL Round Up

Laugh and enjoy!

“Cinema Classics: The Birds” (4605 with John Mulaney)

“Uncle Ben” (4606 with Dave Chappelle)

RoboCop (1987)

I’m not surprised I liked RoboCop, but I am surprised at why I liked RoboCop. Not only is this a boss action blockbuster, it’s an investigation into consumerism and the commodification of the human body. It’s also a critique of institutions that treat crime like statistics instead of actions done by people that impact people. That said, it’s also movie about a guy who’s fused with a robot and melts another guy’s face off with toxic sludge, so there’s a reason I’m not listing this under the Critic section. Crowd: 9/10 // Critic: 8/10

Double Feature – ‘80s Comedies: National Lampoon’s Vacation (1983) + Major League (1989)

The ‘80s-palooza is in full swing! In Vacation (Crowd: 9.5/10 // Critic: 8/10), Chevy Chase just wants to spend time with his family on a vacation to Wally World, but wouldn’t you know it, Murphy’s Law kicks into gear as soon as the Griswold family shifts from out of Park. The brilliance of the movie is that every one of these terrible things is plausible, but the Griswolds create the biggest problems themselves. In Major League (Crowd: 8.5/10 // Critic: 6.5/10), Tom Berenger, Charlie Sheen, and Wesley Snipes are Cleveland’s last hope for a winning baseball team. Like the Griswolds, mishaps and hijinks ensue in their attempt to prevent their greedy owner from moving the Indians to Miami, but the real win is this movie totally gets baseball fans. Like most ‘80s movies, not everything in this pair has aged well, but they brought some laughs when I needed them most.

This Time Next Year by Sophie Cousens (2020)

They’re born a minute apart in the same hospital, but they don’t meet until their 30th birthday on New Year’s Day. So, yes, it’s a little bit Serendipity, and it’s a little bit sappy, but those are both marks in this book’s favor. This Time Next Year is a time-hopping rom-com with lots of almost-meet-cutes that will have you laughing, believing in romantic twists of fate, and finding hope for the new year.

Double Feature – ‘80s Angsty Teens: Teen Wolf (1985) + Uncle Buck (1989)

In the ‘80s, Hollywood finally understood the angsty teen, and this pair of comedies isn’t interested in the melodrama earlier movies like Rebel Without a Cause were depicting. (I’d recommend Rebel, but not if you want to look back on your teen years with any sense of humor.) In Teen Wolf (Crowd: 8/10 // Critic: 5/10), Michael J. Fox discovers he’s a werewolf.one that looks more like the kid in Jumanji than any other portrayal of a werewolf you’ve seen. It’s a plot so ‘80s and so bizarre you won’t believe this movie was greenlit.

In Uncle Buck (Crowd: 8/10 // Critic: 7.5/10), John Candy is attempting to connect with the nieces and nephew he hasn’t seen in years, including one moody high schooler. (Plus, baby Gaby Hoffman and pre-Home Alone Macauley Culkin!) This is my second pick from one of my all-time fave filmmakers, John Hughes (along with National Lampoon’s Vacation, above), and it’s one more entry that balances heart and humor in a way only he could do. You can see where I rank this movie in Hughes’s pantheon on Letterboxd.

Lord of the Rings memes

This month on SO IT’S A SHOW?, Kyla and I revisited The Lord of the Rings, a trilogy we love almost as much as we love Gilmore Girls. You can listen to our episode about the series on your fave podcast app, and you can laugh through hundreds of memes like I did for “research” on Twitter.

Nothing to See Here by Kevin Wilson (2019)

Most adults are afraid of children’s temper tantrums, but can you imagine how terrified you’d be if they caught on fire in their fits of rage? That’s the premise of this novel, which begins when an aimless twentysomething becomes the nanny of a Tennessee politician’s twins who burst into flames when they get emotional. The book is filled with laugh-out-loud moments but never leaves behind the human emotion you need to make a magical realistic story.

An Officer and a Gentlemen (1982)

Speaking of aimless twentysomethings and emotion, feel free to laugh, cry, and swoon through this melodrama in the ‘80s canon. Richard Gere meanders his way into the Navy when he has nowhere else to go, and he tries to survive basic training, work through his family issues, and figure out his future as he also falls in love with Debra Winger. So, yeah, it’s a schamltzier version of Top Gun, but it’s schmaltz at its finest. Crowd: 8.5/10 // Critic: 7.5/10

November Critic Picks

Double Feature – ‘40s Amensia Romances: Random Harvest (1942) + The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947)

Speaking of schmaltz at its finest, let me share a few more titles fitting that description. In Random Harvest (Crowd: 8/10 // Critic: 8.5/10), Greer Garson falls in love with a veteran who can’t remember his life before he left for war. In The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (Crowd: 8.5/10 // Critic: 8.5/10), Gene Tierney discovers a ghost played by a crotchety Rex Harrison in her new home. Mild spoiler: Both feature amnesiac plot developments, and while amnesia has become a cliché in the long history of romance films, Harvest is moving enough and Mr. Muir is charming enough that you won’t roll your eyes. You can see these and more romances complicated by forced forgetfulness in this Letterboxd round up.

The African Queen (1951)

It’s Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn directed by John Huston—I mean, I don’t feel like I need to explain why this is a winner. Bogart (in his Oscar-winning role) and Hepburn star in a two-hander script, dominating the screen time except for a select few scenes with supporting cast. The pair fight for survival while cruising on a small boat called The African Queen during World War I (in Africa, natch), and the two make this small story feel grand and epic. Crowd: 8.5/10 // Critic: 9/10

Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949)

A young man’s (Dennis Price) mother is disowned from their wealthy family because she marries for love. After her death, he seeks vengeance by killing all of the family members ahead of him in line to be the Duke D'Ascoyne. The twist? All of his victims are played by Sir Alec Guinness! Almost every character in this black comedy is a terrible person, so you won’t be too sorry to see them go—you can just enjoy the creative “accidents” he stages and stay in suspense on whether our “hero” gets his comeuppance. Crowd: 8/10 // Critic: 8.5/10

Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife (1937)

What would you do if you found out you were to be someone’s eighth wife? Well, it’s probably not what Claudette Colbert does in this screwball comedy that reminds me a bit of Love Crazy. This isn’t the first time I’ve recommended Colbert, Gary Cooper, or Ernst Lubitsch films, so it’s no surprise these stars and this director can make magic together in this hilarious battle of the wills. Crowd: 9/10 // Critic: 8.5/10

The Red Shoes (1948)

I love stories about the competition between your life and your art, and The Red Shoes makes that competition literal. Moira Shearer plays a ballerina who feels life is meaningless without dancing—then she falls in love. That’s an oversimplification of a rich character study and some of the most beautiful ballet on film, but I can’t do it justice in a short paragraph. Just watch (perhaps while you’re putting up your hot pink tinsel tree?) and soak in all the goodness. Crowd: 8/10 // Critic: 10/10

The Third Man (1949)

Everybody loves to talk about Citizen Kane, and with the release of Mank on Netflix, it’s newsworthy again. But don’t miss this other ‘40s team up of Joseph Cotten and Orson Welles. Cotten is a writer digging for the truth of his friend’s (Welles) death in a mysterious car accident. Eyewitness accounts differ on what happened, and who was the third man at the scene only one witness remembers? 71 years later, this movie is still tense, and this actor pairing is still electric. Crowd: 8.5/10 // Critic: 9/10

The Untouchables (1987)

At the end of October, we lost Sean Connery. I looked back on his career first by writing a remembrance for ZekeFilm and then by watching The Untouchables. (In a perfect world I would’ve reversed that order, but c’est la vie.) In my last selection from the ‘80s, Connery and Kevin Costner attempt to convict Robert De Niro’s Al Capone of anything that will stick and end his reign of crime in Chicago. Directed by Brian De Palma and set to an Ennio Morricone soundtrack, this film is both an exciting action flick and an artistic achievement that we literally discussed in one of my college film classes. Connery won his Oscar, and K. Cos is giving one of the best of his career, too. Crowd: 9/10 // Critic: 9.5/10

Remember the Night (1940)

Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck in my favorite team up yet! Double Indemnity may be the bona fide classic in the canon, but this Christmas story—with MacMurray as a district attorney prosecuting shoplifter Stanwyck— is a charmer. I’ve added it to my list of must-watch Christmas movies—watch for some holiday cheer and rom-com feels. Crowd: 8.5/10 // Critic: 8.5/10

Photo credits: chr paperie. Books my own. All others IMDb.com.

#The Untouchables#The Third Man#The African Queen#The Red Shoes#Kind Hearts and Coronets#Bluebeard's Eighth Wife#The Ghost and Mrs. Muir#Random Harvest#An Officer and a Gentlemen#Nothing to See Here#Kevin Wilson#This Time in Next Year#Sophie Cousens#The Lord of the Rings#Teen Wolf#Uncle Buck#National Lampoon's Vacation#Major League#SNL#Sister Act#RoboCop#Remember the Night#Round Up

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

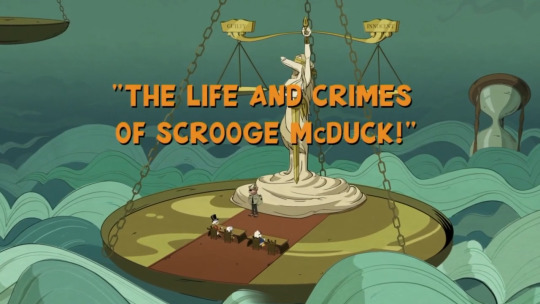

DuckTales 2017 - "The Life and Crimes of Scrooge McDuck!"

Story by: Francisco Angones, Madison Bateman, Colleen Evanson, Christian Magalhaes, Ben Siemon, Bob Snow

Written by: Bob Snow

Storyboard by: Stephanie Gonzaga, Krystal Ureta, Brandon Warren, Hayley Foster

Directed by: Matthew Humphreys

I'm not the only judge around here.

The episode begins with Scrooge and Louie dealing with a bunch of furry, multiplying monsters that are in no way supposed to be the Tribbles from Star Trek. They're Gribbles, they're completely different. Before they can deal with them entirely, and almost immediately after Scrooge tells Louie how he should accept responsibility, they are suddenly summoned into the All-Powerful Karmic Court. This otherworldly court features a seemingly all-powerful bailiff, and a giant Lady Justice holding a scale that will hold Scrooge's innocence and guilt. Who was responsible for getting Scrooge and Louie into this Karmic Court?

None other than Doofus Drake, who is just as creepy as he always was in this reboot. He makes his entrance by being wheeled in while wearing a strait-jacket, an obvious reference to Silence of the Lambs, he puts chap-stick all over his face, and, right before a commercial break, he appears to start an attempt to lick Louie's face. We get it, the character was bad and unlikeable in the original, so the new version of the character has to be disgusting and intentionally unlikeable. They could have just not have him appear, put him on a milk carton somewhere, or, since this is a reboot, they could have made him a different character entirely like they did with Burger Beagle, but instead, we get this Licky McCreepo.

Using the combined money and supernatural powers of him and his witnesses, Doofus, wanting revenge, er, justice over losing his inheritance to his own family, managed to get a supernatural summon to sue Scrooge McDuck out of the fortune, land-holdings, and treasure that would have been Louie's inheritance. Why? Because he ruined their lives! Scrooge immediately balks at these accusation that he can be guilty of ruining anyone's life, saying that he got everything fair and square and he has done nothing wrong. The Bailiff, acting as the judge as the giant Lady Justice can only nod or shake her head, has to keep telling him to sit down and be quiet as the plaintiff and his witnesses bear their case. As Scrooge can't help but make himself look guilty in the face of the all-powerful and all-seeing Karmic Court, it's up to Louie, the irresponsible schemer that Scrooge was scolding minutes before, to help him against three different shorts, er, three different witnesses! Our first one is...

Witness #1: Flintheart Glomgold!

Or, as he puts it as he jumps out of the door:

Flintheart: FLINTHEART GLOMGOLD, HA HA HA HA HA!

Yes, he even introduces himself with lightning strikes behind him. I'd like to think he requested the court supply those, as that was also the explanation for the Hannibal impression. It does not matter to the Karmic Court that the plaintiff and witnesses are acting like villains, as the case is supposed to be that Scrooge's actions have led them this way in the first place. We get a flashback, courtesy of the Karmic Courts power to get video clips of anything that happened in the past. Having video clips of things that couldn't possibly have been recorded is a reason for the supernatural element to this court. It is magic, it does not need to be explained.

No, this isn't about his former Duke Baloney persona, though I like how they mention that right in the beginning, but how he managed to steal the heart of Duckburg from him. It happened all the way back in 1987, as they sure liked that year for reasons that should be obvious. Back then, Duckburg was in a state of Glomgold Fever, as reported by Webra Walters. Her joke, besides being an obvious parody of Barbara Walters, is that she has a lisp. In the beloved adventurers latest adventure, he's going into a cave full of sharks and booby traps to get a large, sharktooth-shaped diamond for the people of Duckburg. He even takes Webra Walters and a cameraman with him, all so they can report on his benevolence. He is trying so hard to make himself look like a hero, though I'd argue putting a reporter in danger for the sake of his own ego is a hint that things are not right with this. Well, besides the fact that he's Glomgold, but the people in 1987 didn't know that.

However, that unapproachable and miserly billionaire, Scrooge McDuck, shows up with a grappling hook, swinging effortlessly. Glomgold, in his anger, accidentally pushes Webra off the rock she was standing on. As she grabs onto the ledge for dear life, Glomgold sees this reporter struggling to not get eaten by sharks and accuses her of being in cahoots with Scrooge, and jumps away to that diamond without even trying to save her. As Scrooge manages to get to the diamond and Glomgold ending up holding on to a stalactite after accidentally hitting a booby trap that caused that rock Webra barely managed to climb back up to start sinking. As Debra starts with what she thinks is her last report on how Glomgold has revealed his stupidity and cowardice, assumedly ending Glomgold Fever for good, Scrooge uses the grappling hook to save her and the cameraman, the diamond still strapped to his back.

Needless to say, Scrooge becomes the hero of Duckburg as Webra reports that the originally "miserwy" Scrooge is now showing his "herowic" side, while Glomgold Glomgold then laments at the days he had to hang on to the stalactite, eventually having to make friends with the sharks that infested the cave's waters. It's here where we learn why Glomgold loves sharks so much: because it's the only love he had after that fateful day. Revealing key moments of the villain's past that shaped them into the villains they became is going to be a theme with all of the witnesses, bringing some more importance to this episode. I'll admit that this part is the weakest of the three to me, though I can't deny Glomgold's charm in his reminiscence of his friendship with the sharks. Also, his unforgettable intro.

There is one moment that definitely did not shape them into the villains they became: Scrooge. At least, according to Scrooge himself, who continues to blast the court for even considering this to be evidence against him. The bailiff has to conjure up a muzzle at some point, though even that does not last. Louie eventually comes up to the court and tells them that he was clearly evil even before this incident, and the court. This goes to show that the court is indeed all-seeing, though I do still have a feeling that this court seems to be really easily convinced, as they seem to accept it. They probably should have accepted the "dooming Webra to a shark-caused death" as evidence against the Plaintiff, but this isn't even the worst the court gets with this sort of thing. There's no reason to complain, it's currently Innocent 1, Guilty 0.

Witness #2: Ma Beagle!

Next, it's Ma Beagle, and she wants to get the deed for the town the Beagles rightfully owned before it was stolen by that crook. While the last story revealed Glomgold's shark affinity, this one is the very backstory for how the Beagle Boys became the enemies of Scrooge. We finally get the story behind that painting of Scrooge McDuck and Grandpappy Beagle on how he managed to get the deed for the place. It's been shown in that picture that hangs on Scrooge McDuck's wall, but this is the first time we actually get to see what events that picture depicted, taking place long ago in a place known as Fort Beagleburg.

To make a long story short, it was an arm wrestling match, with Grandpappy as the undefeated champion. Scrooge shows up, talking about how this place used to be known as Fort Duckburg, and he offers to buy the town with his endless riches. Putting his money down on the table, Grandpappy and Scrooge agree to an arm wrestle for the fort's deed, the former getting praise by his daughter that he never lost. However, Scrooge proves that "never" rarely lasts, as much sense as that makes, and manages to defeat him using his wit. He also reveals him to be a cheat, once again revealing some villainy on the part of the Plaintiff that the all-powerful Karmic Court seems to ignore. In fact, unlike Glomgold and his former Glomgold Fever, there's no sense of heroism with these guys at all. In fact, they're all wearing the masks that would be made famous by their descendants.

Scrooge: Pleasure doing business with you! (Takes deed and the cup of juice Young Ma was drinking)

Young Ma Beagle: (crying) Aw, I can't believe you-

(video pauses)

Sure, Grandpappy Beagle was a cheat, but Scrooge does admit that it was unnecessarily mean to young Ma Beagle, and this would be a major cornerstone in her becoming the evil mastermind that headed the Beagle Boys. Lady Justice decides this is a win for Guilty, teleporting Ma to the Guilty side. Much like the wrestling episode, the episode's tension would be completely gone if one side went 2-0 unless they were planning on more than three witnesses. However, Louie isn't going to deal with that, and points out that the young Ma Beagle's line was clearly cut off, which it was. Again, for an omnipotent and omniscient karmic court, not only can't they keep a muzzle on Scrooge, they sure like changing their mind. Then again, this seems to work for the villains as well. At 2-0, it seems like Doofus is doomed to have his case dismissed, but he has one more short, er, witness:

Witness #3: Magica De Spell!

Right from her appearance and despite Louie gloating that he can totally take her case on, Scrooge realizes this is the one that may outweigh the other two. We flash back to a time where Magica is currently controlling an entire town's wealth and food with the power of her magic. In fact, she's not alone, as she reveals she's not an only child.

We get to meet a brand new character: Magica's brother Poe De Spell, making his first appearance in the series. One may guess by the amount of guilt Scrooge is showing that it is also his only appearance, and they are correct. To give more of a description, these twin sorcerers are causing chaos among the people they ruthlessly rule over, turning people into various animals, including a daddy goat that is expected to give them milk. Don't think of that too hard. While Magica is just as evil as she ever will be, it's Poe that ends up being the closer to Earth one. This all changes when Scrooge comes up, and, much like the Beagles, he manages to defeat Magica and Poe with his wit and make off with the money. Some of it went to rebuilding farms.

Of course, the worst part is the reason why Poe is missing. I'll keep this one vague as it is a major crux of the episode, as this is mainly caused by Scrooge being selfish. Even though Magica and Poe are clearly villains, this is one true The episode does build up more and more in both Scrooge's guilt and the quality of the segments. One may guess Poe's fate judging by the author he's clearly named after, and if they can't guess, they haven't gotten to that part in their English class.

What's important is that this is the one where even Louie has to admit that he can't weasel his inheritance, er, Scrooge's innocence out of this one. The ending seems like it's going to go into this cliche where they just admit Scrooge's guilt and the court decides that's good enough to let him off the hook, but they throw a few curveballs at that. As much as I don't want to spoil it, it's hard to believe Scrooge and Louie are going to lose their fortune, land, and treasure, especially an episode before the finale, but I think the way the episode ends, while feeling a bit rushed as a lot of events happen in the last minute, is good enough for me to judge this episode as innocent.

How does it stack up?

I debated whether this should be 3 or 4 Scrooges, and I felt this shouldn't get the same rating as Kit Cloudkicker despite being a good showing of Louie's cleverness. With an okay first part, a second part that is good to see, and a third part that's quite interesting, I'd put this at the same level as the decent Split Sword of Swanstantine. Unfortunately, with DuckTales 2017, decent can only go so far. 3 Scrooges.

Finally, after facing off against all of these non-FOWL related villains in a Karmic Court, the McDucks get to face off against FOWL once and for all.

← The Lost Cargo of Kit Cloudkicker! 🦆 The Last Adventure! →

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE TRAGEDY OF AN INSECURE KING & THE OVERPROTECTIVE QUEEN

The Wars of the Roses was a far more complex civil war that didn’t just bottle down to a power struggle between the two dominant factions of the Plantagenet House: Lancaster & York. While the Duke of York wanted to take control of the country because he believed he could do a better job than all the people working for Henry VI; Margaret was aggresively trying to prevent him from having any influence because she believed that too much power in the hands of someone with a strong claim to the throne, could get ideas that he should be the one wearing the Confessor’s crown. Margaert also came from a line of authoritative women who didn’t shy away from the political scene, and took matters into their own hands to safeguard their families’ fortunes. In Margaret’s eyes, what she was doing was no different. Her prayers had finally been answered. She had a son, succeeded in her primary duty as royal consort. Now all that was left for her to do, was safeguarding her baby boy’s legacy.

“Henry VI may have been on the road to recovery, but he continued to display a lack of interest in the affairs of his realm. He turned more than ever to religion to find solace, leaving Queen Margaret and Somerset holding the reins of power. Her position had been immeasurably strengthened by the birth of her son, which gave her more reason than ever to safeguard the Crown. She turned her attention to trying to rally as much support as possible, as well as persuading her husband that York was vying for the throne. York, meanwhile, knew that his enemies would soon try and move against him and was not prepared to wait for them to strike. Together with Warwick and Salisbury, he began raising an army with which to confront them. All three men owned extensive estates in the north, and combined were a force to be reckoned with.

A great meeting of the King’s Council was planned for 21 May at Leicester, but York and his allies were deliberately excluded. Instead, they were all summoned to present themselves in front of the Council, but York was wary. Fearing the consequences now that Somerset was free, and suspecting that charges would be brought against him and his supporters, he took matters into his own hands: he and his army began to march south, intent on securing his own restoration to power and destroying Somerset for good.

On 1 May, Jasper Tudor left London with the King on the first stage of their journey to Leicester. When word reached them that York and his supporters were travelling south with an army, Somerset convinced Henry that York was coming to claim the throne. He immediately raised a force in readiness to defend the monarch, fully aware that he, himself, was York’s real target. A violent outcome seemed impossible to avoid: the Wars of the Roses were about to begin.

On 22 May, the political tension between the court party and the Duke of York and his supporters finally erupted into violence. Accompanied by Jasper Tudor, Somerset and ‘many lords’, Henry VI had reached St Albans, twenty-two miles north of London, when York intercepted them. Though he had the bigger force, neither he nor the royal party really wanted to fight. Instead, York attempted to persuade Henry to hear his complaints, and in so doing left him in no doubt as to his wishes: chiefly the removal and punishment of Somerset. His efforts were in vain, for the King –however weak- was not prepared to be dictated to and steadfastly refused to hand Somerset over. His men were heavily outnumbered, but his unyielding response made it clear that if York wanted to settle the matter, he would not be able to do peaceably.

Feeling that there was no alternative, York made the drastic decision to attack. According to a Milanese envoy, informed by a messenger, when the King’s party ‘were outside the town they were immediately attacked by York’s men’. By taking such an aggressive stance, York was fully aware that many would believe he had taken up arms against his lawfully anointed king –and in so doing committed treason. The King’s forces, led by Humphrey, Duke of Buckingham –a man who would later be closely connected with Margaret Beaufort- were badly prepared and taken aback by the full ferocity of York’s charge. Despite being caught by surprise, the royal party initially held their own, but they were defeated when Warwick managed to lead a force into the town by unguarded back lanes. The result was disaster for the royal army, many of whom fled when they perceived the direction that the battle was taking. Although Henry’s men, including Jasper Tudor, fought valiantly, in less than an hour York had won the day thanks to the Earl of Warwick’s successful routing of the royal forces. The casualties on the King’s side were heavy and included the Earl of Northumberland and Lord Clifford. Many were also badly injured, among them Margaret’s cousin, Henry Beaufort, Somerset’s heir. He would survive his injuries, though his father would not be so fortunate.

Realizing that the battle was lost and that York was out for his blood, Margaret’s [Beaufort] uncle Somerset attempted to take refuge at the Castle Inn in the town. It was not long, however, before York’s men had surrounded it: for Somerset –so long protected by the King and Queen- this time there would be no escape. Though he attempted to fight his way out and did so bravely, killing four men in the process, he was soon struck down. As John Benet’s Chronicle reported, ‘all of the Duke of Somerset’s party were killed, wounded or at the least despoiled’. With his death, the battle ceased … But for the King, who had stood watching the violence that was playing out around him, there were to be more direct consequences. On Warwick’s orders, Yorkist archers began to shoot at his bodyguard, killing and injuring several in the process –the injured included Jasper Tudor, the Duke of Buckingham and the King himself.

Although Henry ‘was hurt with the shot of an arrow in the neck’, his injuries were not serious, but that was not an end to the matter. More alarming was that York succeeded in capturing him. Having gained control of the King’s person, according to the Milanese ambassador, ‘the Duke of York went to kneel before the king and ask pardon for himself and his followers, as they had not done this in order to inflict any hurt upon his Majesty, but in order to have Somerset. According, the king pardoned them’. York had successfully eliminated his enemy, and in so doing knew that he had taken a huge step in securing his return to power …” - The Uncrowned Queen by Nicola Tallis

Yet, as Nicola Tallis later pointed out in her biography of Margaert Beaufort, Margaret of Anjou’s mistake was expecting that she’d be allowed to play any part in her husband’s government.

England’s contempt for uppity consorts was still not far behind. Since the times of the Angevin kings with the would-be-Queen, Matilda and later with the Plantagenets with Isabella Capet, the lords distrusted any consort who made her ambitions known.

There is no reason to believe that prior to the first Battle of St. Albans (1455), York had any designs on the throne. Like so many other royal relatives, the most he might have aimed for to is reaping the benefits of doing a good job. Margaret’s animosity and suspicious nature, and Henry VI’s incurable indecisiveness, personal insecurites and eagerness to please everyone pushed a man like the Duke of York (who was the entire opposite of Henry VI) on the edge. Before long, BOTH Margaret and the Duke of York reached their breaking point.

In her biography of Henry VI, historian Lauren Johnson points out that the last Lancastrian King was one of the most brilliant minds of his age. Several of his contemporaries remarked in his early teens that he was a treasure trove of knowledge, but his strict upbringing and uncles’ quarrels had made him extremely insecure. It is nearly impossible to say how he would have turned out if Henry V lived. But given the huge emphasis his father put on education, balanced with military instruction, it can be assumed that Henry VI would have been less obsequious towards sycophant courtiers and probably handled the whole animosity towards Margaret of Anjou and the Duke of York (that’s assuming he would have still married Margaret) far better.

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

What exactly do you think Henry VI thinks of his uncle Humphrey?

I'm glad you said what I think Henry VI thought of his uncle! The personal thoughts of any medieval individual are generally out of reach for us (there are exceptions; for example, we can tell that Henry V was pretty pissed off at his brother, John, Duke of Bedford here). It's even more difficult in the case of Henry VI, where historians have such wildly diverse opinions. The likes of John Watts and K. B. MacFarlane, who view Henry as a void around which kingship in his name was exercised (by his minority council, by his "favourites" Suffolk and Somerset), would probably say that Henry didn't think very much about his uncle or, well, anything. But even looking at the historians (e.g. Ralph Griffiths, Bertram Wolffe and Lauren Johnson) who ascribe to Henry far more agency in his reign will give us vastly different ideas of the relationship between Henry and Humphrey.

Johnson, for examples, depicts Henry as Humphrey's victim, depicting his quarrels with Cardinal Beaufort and his pro-war stance as a source of mental distress for Henry. She also depicts Humphrey as fully complicit in his wife Eleanor's alleged plot against Henry (there is nothing alleged about the plot for Johnson, of course) and arranging for his nephew to be sexually harassed.* For Wolffe, Humphrey is more the victim of a spiteful Henry - for instance, he argues that the treatment of Eleanor was an angry overreaction by Henry, who still bitter that Humphrey opposed his intention to release Charles, Duke of Orleans the previous year.

But what do I think?

Humphrey was pretty obviously a thorn in Henry's side. He seems to have advocated for Henry to get more involved in ruling, even though the circumstances weren't great for an inexperienced king and it appears Henry disliked the experience. As Henry matured, the policies he favoured were frequently in conflict with the policies Humphrey advocated for - as Humphrey often made clear (cf. his actions around the release of Charles, Duke of Orleans). What was often a common thread in Humphrey's chosen policies were that these were Henry V's policies. Humphrey seemed to be simultaneously urging Henry VI to greater independence but insisting that he exercise this independence through following the policies of his father.

It's easy to imagine that this became a sore spot for Henry. It's not nice to be constantly compared to someone else and always be found lacking. It's not nice to be someone who others are trying to shape into someone you're not. The fact that Henry was constantly being compared to his dead father who was becoming heavily mythologised would have only made it worse. It's really easy to imagine Henry coming to resent his father for that and easier still to see him resenting Humphrey who seems to have been the one who stuck at the "your father would've done this, do this, you should be more like your father" the longest.

This advocation of Henry V's policies seems to have led to Humphrey becoming seen as "a man who embodied the qualities Henry V had made them accustomed in a king, and which they were beginning to realize were lacking in their actual king". If Henry believed this too, it may be that he initially found Humphrey to be an intimidating, but not necessarily dangerous, figure - the embodiment of the qualities he was supposed to have, the representative of his father. Even if he didn't share the same view of Humphrey's qualities, Humphrey was, alongside John Duke of Bedford, the closest paternal blood relation Henry VI had and the one Henry saw the most of. He may have seen Humphrey as a threatening figure because of the popular belief that he had the qualities for kingship that Henry himself lacked (though, IMO, he wouldn't have been a good king) and, following Bedford's death in 1435, was Henry VI's heir.

If Henry didn't already view Humphrey as a threat, the accusations of treasonable necromancy against Humphrey's wife Eleanor would have likely made Henry come to that view. Most historians argue that Humphrey ended up estranged from Henry and alienated at court as a result of his wife's downfall. It may be that Henry (and others) suspected Humphrey had been aware of or part of the plot - although there is no evidence that this was ever suspected, much less that Humphrey was involved. At the very least, the accusations suggested that Humphrey was a figure others could see as a king and that he was an untrustworthy figure of poor judgement.**

It's pretty clear that from 1441 on, Humphrey was on the outs with Henry but it doesn't seem to be motivated entirely by fear. Henry made a number of grants in the 1440s of titles that Humphrey held to various people in the event of Humphrey's death (one of the most notable is Suffolk receiving the reversion of the earldom of Pembroke). One chronicle claims that Henry had forbidden his uncle from his presence since 1445 or 1446 and reputedly an armoured guard to fortify himself against his uncle. In 1445, Henry publicly humiliated Humphrey in front of a French embassy (according to Wolffe, the French ambassadors claimed that Henry "openly express[ed] his pleasure at seeing his uncle's discomfiture" at the treaty).