#that is very different than being taught the alphabet and grammatical structures and how the language itself works.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

are there any apps/websites out there that actually teach you a language?

#duolingo does not teach you a language. it gives you some phrases to memorize.#that is very different than being taught the alphabet and grammatical structures and how the language itself works.#i want to learn languages!!#duolingo will not halo me do that.#i need something formatted to TEACH.#unityrain.txt#language

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comprehensive guide to writing deaf characters

Despite not being intented as a blog resource for writers, we get a lot of questions regarding how to write deaf characters. (and by a lot, I mean like half of questions are about writing)

Since lot of these questions are similar anyway, I wrote up this guide for anyone intending to add deaf characters into their writing. From now on, we shall only answer questions related to writing which AREN’T covered in this guide.

Please, keep in mind that deaf people aren’t a hive mind and this guide is based on our personal experience. We recommend a sensitivity deaf reader if you plan to make any deaf character a big part of your story.

Rest of guide under the cut.

Medical basics

- Deafness can be caused by many factors.

- For people born deaf, common causes are: genetics, illnesses of mother during pregnancy (and meds taken), complicated birth, premature birth, etc.

- For people who become deaf later in life: old age, noise damage, several infectious illnesses (for example meningitis), medication (cancer meds or certain antibiotics), tumours on auditory nerve and in brain, chronic inflammations of middle ear, etc.

- Most people with hearing loss still have some degree of hearing

Terminology

- “deaf” – person with hearing loss

- “hard of hearing” – person with hearing loss, still has some degree of hearing

- “Deaf” – person with hearing loss who is proud of their deafness, is member of Deaf community and culture, communicates in sign language

- “deafened” – person who lost their hearing in later life, often as adult

- “deaf and dumb” – old terminology, now considered insulting

- “hearing impaired” – medical term, often disliked by deaf people

Compensation

- Most hard of hearing and some deaf people wear hearing aids. Their function is similar to glasses, they enhances the remaining sense.

- Hearing aids are often pricey, not covered by insurance and need batteries to recharge

- They can be colourful, however most people use brown to make them less noticeable

- They need to be taken off for sleeping and bathing

- It’s considered rude to touch another’s person hearing aid. Hearing people should not try them out, as they can damage normal hearing.

- Cochlear implant are more complicated, require surgery to insert. They compromise of two parts – inner part (under skull), which stimulates hair cells in cochlea, and outer part (outside on the head and ear), which is sound processor, microphone and battery. Both parts are connected via magnet.

- Hearing via CI is more electrical than normal hearing and doesn’t sound same. After the operation, users must train their hearing and attend many sessions where CI is adjusted. It can take years for users to hear speech or use telephone. Success is very individual.

- CIs are often disliked and criticized by Deaf community as they are seen as a threat to Deaf culture and language. There is also a question of consent – for CI to be successful, children must be implanted at young age (1-7 years) and the decision is usually made by their hearing parents.

- Other compensation: Vibration and light alarms, alarm clocks, baby monitors, door bells. Special phones and headphones. Etc.

Communication

- Children who are born deaf cannot naturally acquire spoken language. (aka from their parents/family) It cannot be learned by lip-reading. They learn it as a second language, often at school.

- Despite the stereotype of deaf people being also mute, most deaf people can speak. However, they often have so called “deaf accents”, because they cannot hear themselves speak. Because of that, some deaf people prefer not to talk, to not be mocked for their accent.

- Natural language of deaf people are sign languages. They are not universal, they have their own grammar and rules, they are not simple pantomime and they are not easy to learn. (see Sign Languages)

- Not all deaf people use sign languages, especially those who become deafened later in life.

- There are specific communication system, which combine spoken languages and sign languages, often used in education. They usually use signs from sign languages and spoken language grammar. The most common is Pidgin Signed English (PSE) or Signing Exact English (SEE). Some deaf people use them instead of sign language, since they grew up with it.

- SimCom is simultaneous communication, speaking and using sign language at the same time. As its basically using two languages at one time, it’s difficult and one language often starts following grammatical structure of other.

- Lip-reading is taxing, difficult and often based on talent. It must be taught. To properly lip-read, there must be good light conditions and you must be able to see the face of speaker.

- Some deaf people use writing to communicate with hearing people – either with paper and pen, or on phone. This way of communication is often time-consuming.

- Deaf people often use interpreters to help them communicate. They usually accompany the deaf person to doctors, authorities, important meetings, etc.

Sign language

- Sign languages are natural languages and not created by one person. They appeared organically over time.

- Every country has their own national sign language. The ones most known and researched are ASL (American Sign Language), LFS (French Sign Language), BSL (British Sign Language), AUSLan (Australian Sign Language). There is about 137+ sign languages in the world.

- Grammar in sign languages is based on 3D spaces and use of face expressions and movement of body. Signs are composed of hands in specific shapes, their movement and placement on the body.

- Most sign language have their own finger alphabet. Most common are one-handed (ASL, LFS) and two-handed (BSL, AUSlan).

- Sign languages are not inferior to spoken languages and can express the same things.

- It takes time and dedication to learn any sign language. Usually at least 3 years for being able to communicate properly and more than 5 to be fluent.

- You can sign with just one hand (that’s how deaf people communicate while eating or holding something, for example)

Education

- Until 1970s, the most common way of teaching deaf children was oralism, a teaching tradition which supressed and forbid the use of sign language and insisted on deaf children learning to speak. It is still often used, despite the fact that many studies prove it fails to properly educate deaf people.

- Modern research has proven that use of sign language in education is beneficial for deaf children and helps them to better understand the material.

- Deaf children can either study at school for deaf or be integrated into regular school. Deaf schools used to be very common in past, as they were only available means of education for most deaf people. Kids lived in dormitories. Whether sign language was/is used there depends on the school. Some even had/have deaf teachers.

- Nowadays, most kids study in regular school along with hearing kids. If the school is good, they offer proper compensation – eg. interpreter in class, note taking services, hearing devices, etc. Some schools still sucks, however.

- Integrated kids can suffer from isolation, bullying and discrimination from teachers.

- There are colleges in USA which focus on deaf students and sign language. The most famous is Gallaudet University, Washington, D.C.

Family

- 90% of deaf kids are born to hearing parents. Hearing parents often struggle with the disability of their child. In general, lot of hearing parents prefer to give their kids CI, to make them more “hearing”.

- Deaf parents generally have hearing kids. Those kids are then called CODA – children of deaf adults. CODA often speak sign language well. In general, they are either very involved with Deaf community or not all and avoid it all costs. Lot of CODA children become interpreters.

- Every family is different in how they communicate. Some use sign language. Some only spoken language, requiring the deaf member to lip-read. Some use combination of two or create their own home signs. If only certain members of family learn to sign, it’s usually mother or some other female family member (sister, grandmother).

Deaf culture/community

- A community of Deaf individuals who use sign language as their primary means of communication, are proud of their deafness and their culture. They do not see their deafness as disability/disease, but something that connects them, makes them different from others.

- Deaf people often meet up in clubs, there is big emphasis on community, meeting together, communal experience, etc.

- Term “Deaf gain” is used – what deafness gives us, instead of the usual what deafness takes away from us. What is important is “seeing”, not “absence of hearing”.

- Deaf culture has its own set of social rules/etiquette. Deaf people are generally more blunt and to the point than hearing people. There are special rules for getting attention – eg tapping on shoulder, turning lights on and off.

- There is a big tradition in storytelling and poetry in sign language, especially ASL. Other visual art – videos, paintings and sculpture are also popular.

- Deaf community has lot of members who are LGBT+ and has its own deaf organizations for said people. Generally, deaf community is more accepting when it comes to LGBT+ issues then general public, although exceptions exists.

- Not every country has a strong Deaf community – the biggest one is in USA. In some countries, deaf people are isolated.

Discrimination

- Specific term for discrimination against deaf people is “audism” (not to confuse with autism). General term for discrimination against disabled people, “ableism”, is also used sometimes.

- Deaf people often face discrimination especially when it comes to access to information and unwillingness to offer proper accommodation to them.

- Movies/Tv shows/videos lack subtitles or closed captioning. Video games have no alternative way of showing audio cues. Lectures, festivals and public events are often without interpreters.

- There have been numerous cases of arrests and deaths of deaf people after encounters with police due to communication.

- Hospitals and doctors are often without interpreters and neglect to inform the deaf patients properly. Access to authorities and courts is also problematic.

- Deaf people have difficult time finding employment due to prejudice. Even if they do find a job, employers often refuse to offer proper accommodation.

- Many deaf people also struggle in education – see above.

Common mistakes and stereotypes when writing deaf characters

- Lip-reading as a superpower, which makes deaf person basically hearing anyway

- Wearing Hearing aids at night and/or other people touching them and taking them off.

- Cochlear Implants presented as “cure” or “miracle” which makes a deaf person into hearing person

- Being able to learn sign language in record time (aka in several days)

- “Happy” ending being deaf person losing their deafness via cure/miracle/magic

- Deaf people being bitter and lonely (yes, there are deaf people who are bitter and lonely, but it’s not our defining trait and it’s not *that* common)

- Using deafness as a “cute” trope to increase angst levels in your story because being deaf sucks, right? ( -_________-)

- Deaf person only having hearing friends (it’s often the opposite, aka most friends of Deaf people are also Deaf). Same goes for dating.

- Superpowers or magic that basically cancels out deafness

- Creating your own Name signs for your characters (pls really don’t)

- Sign language = English with signs

- Framing the narrative as a “person overcoming their disability”

- Including deafness as a punishment for the character

- The only deaf character in the story is the villain (“bonus” points for ‘deafness turned them evil’)

- Inspiration porn – see the link

Also, keep in mind that:

- Deafness isn’t a disease and isn’t actually contagious (can’t believe I have to say this)

- We very rarely date people who don’t bother to learn how to communicate with us.

- Deaf people can and do drive. We also travel. Use internet. Swim. Read.

- “Shockingly”, we can tell apart yawning and screaming.

- People who were born deaf think in sign language and asking about it really doesn’t make you a philosopher

2K notes

·

View notes

Link

“SEE is good for learning English because it includes all the grammatical aspects of English such as past tense. SgSL is broken English just like Singlish![1]”

“No! SEE is not a language but a system/code. SgSL is a true language!”

I vividly recall the summer of 2016. I attended the Singapore National Deaf Youth Camp that occurred from May 20 to 22, 2016 as part of my 7-week internship at the Singapore Association for the Deaf (SADeaf). Through observations and my interactions with the camp participants, I realized that a hybrid of different languages and manual communication systems were being used by different individuals in Singapore to communicate with one another. These included Singapore Sign Language (SgSL), American Sign Language (ASL), Pidgin Signed English (PSE), Signing Exact English II (SEE-II) and spoken English. It was all very fascinating to observe.

One of the sessions scheduled in the camp programme which aroused my curiosity was the SgSL versus SEE-II debate. Although I have heard that there are still debates between the exact manual representations of the grammar of the spoken language which is akin to SEE-II, and the national sign language happening in various parts of the world, I had never personally encountered anything like it before in any of the Deaf camps and workshops I had attended while living abroad. At the camp, participants were divided into the group they supported and they were given opportunities to debate their position. The quote at the start of this essay introduced the fundamental arguments of each side.

As I reflected further, I began to see that this debate was connected to my life, and to fundamental issues of being d/Deaf in Singapore. Using my own lived experiences as a way to think about these issues, I examine what this history means, and argue that being Deaf is a reflection of the need to identify with Deaf culture and with sign language.

Between deaf and Deaf

Deaf Studies as a field of study is concerned with the experiences of the Deaf. It grew out of the Deaf Rights Movement historically and focuses on the experiences of Deaf people, Deaf history and Deaf culture (Myers & Fernandes, 2010). Within the Deaf community, there is a distinction made between being “deaf” and being “Deaf”. Being deaf refers to the medical condition of not being able to hear or having hearing loss, while being “Deaf” refers to one’s identity and affinity with the Deaf community, usage of sign language, and Deaf culture. Members of the Deaf community have different degrees of hearing loss ranging from mild to profound levels.

In this vein, I have a confession to make. I never used to identify as “Deaf” or even “deaf”. Since young, I have unknowingly categorically rejected the identity of being d/Deaf.

The reason for this is simple. I had no idea that the word “Deaf” even existed. It was beyond my realm of experience. As for “deaf”, I thought it strange to label myself that, when I could hear conversations relatively well depending on the situation. I also have intelligible speech. To 8-year-old me, “deaf” meant that I could not hear completely nor speak at all. It just didn’t make sense for me to identify as “deaf”.

Instead, I referred to myself as “hearing impaired”. At other times, I would say that I was “partially deaf” or “hard-of-hearing”. I used the term “hearing impaired” during my childhood and teenage years also because it was a term that was imposed on me by my audiologist, my parents, and my teachers at the Canossian School for the Hearing Impaired and St Anthony’s Canossian Primary School. I knew no other more appropriate term to label myself. It also appeared to be the most fitting term to describe myself to other people at that time because people generally understood it as someone with a certain degree of hearing loss with some speech ability. To me and the people around me, the term “deaf” was more degrading than “hearing impaired”. In other words, there is a stigma with being “deaf”.

Thus, I never identified as part of the Deaf community in Singapore during my growing up years. My first contact with any form of signing occurred when my mum brought me to Wesley Methodist Church in 2000 as she had heard that they had a Ministry of the Hearing Impaired (MHI). When I walked into the church service one Sunday morning, I saw someone on stage moving her hands about in sync with the song. A number of people with hearing aids just like me sat in rows on the right end of the auditorium. Some were moving their hands about mimicking the person on stage. When the pastor delivered his sermon, a different person came on stage and moved his hands about to convey the sermon visually to the audience.

My mum also took me to MHI’s SEE-II classes to pick up sign language. As a result, I believed that SEE-II was real sign language and that sign language was merely about signing each word in an English sentence. I learned how to sign the alphabet and picked up some basic signs. I also attended MHI events. Still, I had very little interest in signing and mixing with other people that wore hearing aids like me. After 6 months of attending the church, I lost interest altogether and left.

My exposure to SEE-II under the church ministry was a result of developments in Deaf education in Singapore since the 1950s. It all started when Mr Peng Tsu Ying, who moved from Shanghai to Singapore, established a small deaf school in his home in the 1950s and introduced Shanghainese Sign Language (SSL) as the language of instruction. In 1963, the Red Cross Society’s oral deaf school, which taught deaf children to lip read and orally articulate words merged with Mr Peng’s school to become the Singapore School for the Deaf (SSD). The school had an oral section and a Chinese Sign Section. As such, earlier generations of the Deaf in Singapore were educated in SSL.

In the mid-1970s, Lim Chin Heng, former student at the SSD returned to Singapore after completing his undergraduate education at Gallaudet University in Washington D.C. He introduced the Total Communication (TC) philosophy, ASL and SEE-II to SSD. The shift towards SEE-II as the main mode in educating the deaf was also cemented with the visit of Frances Parson in 1976. Parsons was the global ambassador of TC from Gallaudet College. She trained educators of the deaf in Singapore to use TC, a combined method where sign and speech were used simultaneously (Signal, 2005). Lim subsequently went back to Gallaudet to pursue a Master in Education of the Hearing Impaired in the late 1970s.

Consequently, Mr Peng decided to move away from SSL and implemented the use of the structured SEE-II that followed the rules and conventions of the English language, since English was Singapore’s main official written language. He arrived at this decision after observing that the signing of the deaf students were unstructured (Signal, 2005).

Yet, even while SEE-II was adopted as the official language of instruction in SSD, and younger generations of Deaf and hard-of-hearing children grew up with it, the use of SEE-II has divided the community with some believing it to be effective for teaching literacy in English while others do not see it as a proper language. Some of the Deaf in Singapore have gravitated towards the use of SgSL, which they claim as the language of the Singapore Deaf Community.

I used SEE-II only for a few months in my teens. The whole time I had an inherent bias that sign languages were inferior to spoken languages and that the ability to speak set me apart from other deaf people. To me, it was more important to learn to speak and integrate into the hearing-centric world that we live in. Subsequently, I expended much time and energy attempting to be “hearing” by trying to fit into academic and social contexts with hearing people in order to appear “normal”. As a result, such situations often became a source of stress and anxiety for me. However, I thought I simply had to try to listen harder or I needed a more powerful hearing aid.

For many years the erroneous beliefs I held about myself, other deaf people and sign languages were so deeply embedded in my psyche that I lived in complete oblivion to Deaf culture and community. In short, I was an audist because of such views and attitudes ingrained in me. Audism, a term coined by Dr Tom Humphries in 1977, refers to the discrimination of deaf people based on their inability to speak and hear (Berke, 2018). It is the belief that the ability to hear and speak makes one superior to those that do not possess these abilities.

The road to becoming Deaf

When I graduated from the Singapore education system in 2002, I decided that I wanted to become a teacher of the Deaf. I chose to go to Australia to start a one-year foundation studies program to prepare for entry to university.

In 2004, when I commenced my undergraduate degree at Griffith University, I contacted the Deaf Student Support Program (DSSP) to enquire about accessibility services. As I did not know Australian Sign Language (Auslan), I was provided with a laptop notetaker to sit next to me during lectures and tutorials so I could look at the screen and follow what the professor was saying in class. As I expressed a desire to be able to access Auslan interpreters later on, DSSP arranged for me to meet with a native Deaf signer for an hour weekly to learn Auslan.

My progress in learning Auslan was excruciatingly slow because apart from that one hour of practice every week, I was mostly interacting with hearing people outside of university classes and I had no Deaf friends nor access to Deaf events. At that point, it didn’t occur to me to actively seek them out. I only wanted to learn some sign language as I believed it was good for me to have some sign support via an interpreter. I was still not convinced that sign languages were legitimate languages.

After I picked up some basic Auslan, I was provided with interpreters in my lectures and tutorials. However, my brain kept trying to decipher signs in English grammatical word order while in fact Auslan was “grammatically incorrect” according to the rules of the English grammar. I made progress through interacting with Deaf people and hearing signers on campus. However, I still associated Auslan with “broken English”.

In 2007, the final year of my undergraduate program and taking specialized courses in Deaf education, I developed an understanding of Deaf culture and started to explore what it meant to be Deaf, as well as a deeper understanding of the grammatical structure of Auslan.

I remember one class particularly well. It was a class on Sign Bilingual education where a lecturer showed us examples of how homonyms (words which are spelt the same and have more than one meaning) and homographs (words that have the same spelling that have more than one pronunciation and meaning) were taught using Auslan-English bilingual strategies to Deaf and hearing children in the classroom:

English translation: “The boy kicked the ball.”

Auslan translation (video): BALL BOY KICK

English translation: “The lady is going to the ball.”

Auslan translation: LADY GO DANCE PARTY

English translation: “The children are having a ball.”

Auslan translation: CHILDREN FUN HAVE

The word BALL in each of the 3 sentences was signed differently. It was signed in a way that made sense visually and was conceptually accurate. Selected readings from Johnston and Schembri’s (2007) Australian Sign Language: An introduction to sign language linguistics also gave me a better understanding of how Auslan functions as a language. I realized that Auslan was a bona fide language with its own distinct grammar and structure. It was not “broken English” nor was it an “incomplete language” as I had previously thought, and could enhance reading comprehension.

It dawned on me that SEE-II was conceptually inaccurate as the same sign was often used to represent a word even when that same word had different meanings in different contexts. Therefore, SEE-II did not make any sense at all visually. It is not real sign language but rather just an exact representation of the English language. The usage of SEE-II in reading can hinder comprehension of the text and result in miscommunication.

In addition, after watching a set of Deaf History videotapes, I understood more deeply what Deaf Culture was. Being deaf is not a disability and deaf people including myself are not “disabled”.

I realised that the term “hearing impaired” indicates a defect and implies that something is wrong with the person with hearing loss. The word ‘deaf’ is a pathological term. On the other hand, ���Deaf’ represents a distinct cultural minority with its own norms.

In other words, I was becoming Deaf. With my acquisition of Auslan and interaction with the Deaf community, I could become part of the community. I had a desire to discover more about the Australian Deaf Community. I started attending the Auslan Club organized by Deaf Services Queensland and volunteered at the Australian Deaf Games in January 2008. At the Deaf Games, I ended up chatting with hearing interpreters or hearing volunteers wanting an opportunity to practice their Auslan. I did get the opportunity to have brief conversations with a few Deaf people but felt somewhat out of place as they seemed to mingle with their white Australian friends or people they already knew.

I felt inferior to local Deaf signers as I couldn’t sign or understand Auslan fluently. I still adopted the practices of “hearing” culture in some ways and used my voice at times because I had grown up oral. When I eventually shared with a Deaf friend that it was challenging to fit in with the Deaf community, her response was “You are not deaf enough”.

So even as I had close friends who are Deaf and my Auslan improved, I had difficulty assimilating into the Australian Deaf community. I felt that as an Asian foreigner and oral deaf who learnt Auslan as a second language as an adult, I struggled to find my place and sense of belonging in Australian Deaf culture.

I wondered if I had grown up being Deaf in Singapore, rather than rejecting my Deaf identity, would I have been able to develop a stronger sense of self and be more resilient? Would I not have tried so hard to fit in with hearing people all the time?

From Deaf to Intersectional Identities

When I first stepped into the Gallaudet University campus to start my Masters program, I felt a mixture of trepidation and exhilaration. On one hand, I wondered if I would be able to fit in as a late signer especially since Gallaudet was the epitome of Deaf culture and I was, in the eyes of some, “not Deaf enough”. On the other hand, I was excited to be for the first time living on-campus in a signing environment

Much to my surprise, I soon discovered that my initial fears were unfounded. It was at Gallaudet that I finally found acceptance as well as the freedom to be myself.

I was enthralled by the diversity at Gallaudet. There were Deaf, Deafblind and hearing American as well as international students from all over the world, each with their own sign language – Korean, Japanese, Chinese, Omani and many others. I had expected discussions at Gallaudet to center on the lived experiences of d/Deaf and Deaf identity, but it turned out that there were so many other aspects to consider and reflect on.

At Gallaudet, I was introduced to the term “intersectionality”, coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw. Intersectionality refers to how the many social categories such as race, gender, class, religion, sexuality, disability, and so on, that constitute the individual or group, are interconnected and overlap (Crenshaw, 2016). In other words, each person or group consist of multiple overlapping identities which are intricately interwoven. From an intersectional lens, we can identify how dynamics of oppression and power such as racism, sexism, classism, audism, etc. are created; how power structures marginalize individuals and groups in society.

By adopting an intersectional lens, I began to understand why I never quite found my place in the Australian Deaf Community, which is predominantly white. This new-found understanding compelled me to critically examine other identities that I held. I identify as not only Deaf and/or Hard-of-Hearing but as a woman, a Southeast Asian, a Christian, Chinese-Singaporean, cisgender, English-speaking, oral, and from a hearing family. To discuss and define myself as only a Deaf person is to deny my personhood. My eyes were opened to the rich diversity prevalent within individuals and Deaf communities around the world.

As part of the Chinese race, I am a member of the majority, and I am all too aware of having “Chinese privilege” in Singapore. I had experienced some degree of discrimination in Singapore on account of my perceived hearing disability. However, my experience would differ from those of non-Chinese d/Deaf individuals in multi-racial Singapore.

It is how powerful groups in society construct normalcy and disability that disables me and portrays me as “disabled”. I grew up learning that signing was ‘not normal’ and that the ‘normal’ was to integrate with hearing people and to be able to speak and hear. However, at Gallaudet, I felt “normal” to be able to communicate in sign language. To not know sign language was “not normal”. Accessibility such as voice interpreters for events on the Gallaudet campus was provided for the “signing impaired”, not the “hearing impaired”. When we had a hearing presenter that didn’t know ASL, interpreters were provided for the audience so that they could have access to the presentation in ASL.

had thought I had learned everything there was to learn about being Deaf when I was in Australia. The discussions at Gallaudet helped me to realize that it was only the tip of the ice-berg. In fact, every Deaf person in the world would have a different lived experience even though we all share one thing in common – a Deaf identity.

I also came to learn through reading about Deaf and hard-of-hearing identity labels and through interaction with other Deaf and hard-of-hearing people at Gallaudet, that the term “hard-of-hearing” can be fluid. A friend said to me that she was proud to identify as hard-of-hearing because it meant that she is able to fit in both the Deaf and the hearing cultures with her ability to sign as well as speak. She could simply adjust her language modality to suit the social context.

I had identified as Deaf when I learned Auslan. At the time, I thought that the label “hard-of-hearing” was neither here nor there; neither part of the signing Deaf Community nor part of the hearing community. I realized from my friend’s statement that I could identify as both Deaf and hard-of-hearing, and have done so.

Deafhood

To me, “Deafhood”, a term coined by Paddy Ladd in 1993, refers to having a deep insight into one’s personal journey toward becoming Deaf. In this journey, one experiences identity shifting and learns how sign language and Deaf culture are intricately linked. It is about understanding my own lived experience as a Deaf person as well as those of other Deaf individuals. It is about understanding the dynamics of oppression and how marginalization of Deaf people as a linguistic minority occurs due to the operations of power structures in society that do not give them a voice. It is about how I have come to terms with my past and my healing from painful encounters as I journey towards becoming Deaf. It is also about understanding that every Deaf individual is on his or her own unique journey and is at different points in his or her life. When the Deaf individual embraces his or her Deaf identity and sign language, he or she can truly blossom as an individual and express himself/herself fully.

Rather than see deafness or hearing loss as a problem to be cured, we need to understand that sign language has many benefits and embrace the concept of “Deaf Gain”. Deaf Gain focuses on how Deaf people and sign languages bring many benefits to Deaf people and also the world at large (Bauman & Murray, 2014). It posits that the world is actually a better place because of Deaf people and sign languages than it would be without them. Full access to sign language from birth enables deaf babies without other disabilities to acquire typical language developmental milestones like their hearing peers (Petitto, n.d.). Such accessibility enables the Deaf to achieve their full potential and pursue careers in all kinds of fields. Sign language empowers Deaf people and promotes equality.

Reflections and hopes for the future

My journey leading to the embracing of my Deaf identity, acquiring different sign languages and studying linguistics has led me to conclude that exposure to SgSL for Deaf children in Singapore in the early years is crucial for their language and Deaf identity development, and their resilience.

However, the SgSL versus SEE-II debate at the Deaf youth camp in 2016 which I introduced at the start of this essay points to the polarization between the different groups on the issue. While the Deaf in Australia and the USA are proud of Auslan and ASL respectively, the presence of various camps has meant that language issues in Singapore are more sensitive and delicate. There are d/Deaf individuals who are not convinced about the legitimacy of SgSL and there are those who support SgSL. There also appears to be confusion about what SgSL is. Most of us went through oralism when we were in school, and we do not have the experience of earlier generations of signers to build on. Consequently, there is still a lack of Deaf empowerment and awareness.

I realize it is also important to reflect on how changes in the Deaf community in the USA have impacted Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals in Singapore and the current state of Deaf education. One such event is the Deaf President Now protests of 1988 at Gallaudet University which resulted in the appointment of the university’s first Deaf president (Gallaudet University, n.d.). The protests led to greater activism and recognition of Deaf Culture and ASL, and the phasing out of SEE-II as the mode of instruction. Lim Chin Heng, who first introduced SEE-II to Singapore, was educated at Gallaudet in the 1970s before the DPN protests and when SEE-II was used widely. In contrast, I experienced Gallaudet in the post-DPN era and Deaf Education has undergone major changes since, notably with the implementation of ASL-bilingual methods. In the light of current debates between SgSL and SEE-II in Singapore, I wonder how such lived experiences of Gallaudet will also influence the directions activism over language issues for Deaf people in Singapore will take.

At the same time, I am also highly conscious of how much of my views I can project when interacting with Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals in Singapore. I have been away from home for the last 15 years or so, and often wonder if it is my place to comment or get involved in the SEE-II and the SgSL debate. Would I be influencing the local context with western centric views? However, there are misconceptions about language that need to be addressed. I do very much feel a sense of responsibility to give voice to issues pertaining to Deaf people and sign language, and want to make a contribution to my country where I can. In balancing my hope to share and the concerns of the various groups in the community, it feels as if I am walking on a tightrope at times.

As I navigate this path in the future, I do hope that Deaf and hard-of-hearing Singaporeans will have the opportunity to learn about the grammatical structures of SgSL and come to a deeper understanding of our own language and how it functions. I also hope that more Deaf and hard-of-hearing Singaporeans will have opportunities to develop their Deaf identity and a sense of empowerment. Last but not least, I hope to see future generations of Deaf children become strong advocates for the Deaf community, and for a Singapore that allows for full and equal participation of all its citizens.

Phoebe Tay is a Gallaudet alumni who graduated in 2017 with a MA in International Development and a MA in Linguistics. Prior to that, she worked as an educator of the deaf in Australia. She is currently working for the Deaf Bible Society as a Linguistic Research Specialist under their Institute of Sign Language Engagement and Training (ISLET). She hopes to be able to contribute to the Deaf community in Singapore in the future.

Notes

[1] **NOTE: The following dialogue has been translated directly from SgSL/SEE-II to English. SgSL structure differs from English structure. The contents are based on the author’s notes and memory of the event in 2016.

References

Bauman, D., & Murray, J. J. (2014, Nov 13). An introduction to deaf gain: Shifting our perceptions of deaf people from hearing loss to deaf gain. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/deaf-gain/201411/introduction-deaf-gain

Berke, J. (2018, June 18). The meaning and practice of audism: An audist attitude can be compared to other forms of discrimination. Retrieved from https://www.verywellhealth.com/deaf-culture-audism-1046267

Crenshaw, K. (2016). The urgency of intersectionality. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality?language=en

Gallaudet University. (n.d.) Deaf president now. Retrieved from https://www.gallaudet.edu/about/history-and-traditions/deaf-president-now

Johnston, T., & Schembri, A. (2007). Australian sign language: An introduction to sign language linguistics. Cambridge: University Press.

Ladd, P. (2003). Understanding deaf culture: In search of deafhood. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Myers, S. S., & Fernandes, J. K. (2010). Deaf studies: A critique of the predominant U.S theoretical direction. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 15(1), 30-49.

Petitto, L-A. (n.d.) How do babies acquire language? Retrieved from http://petitto.net/our-studies/mythbusters/how-do-babies-acquire-language/

Signal. (2005). Editorial. Singapore: The Singapore Association for the Deaf.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I was wondering if you could give some tips on learning korean? I have learnt the alphabet but i don't really know how to continue now... Do you have any tips for this? (I know you say you're a beginner but let's be real you know more than i do) Thank you!

Hi anon~! Thank you for your question!

I assume there are more people who have this question, so this will be a long post. Please do keep in mind that I am not an expert in learning languages or Korean for that matter, and I learn languages as a hobby so these will just be my personal tips and recommentations!

Where to start?

So as you mentioned you already taught yourself Hangul, the Korean alphabet. To those just starting out I would recommend starting with Hangul as you did, because many have said it before me, but I will say it again: learning Korean through romanized text only is very difficult. You will sabotage your own progress by doing this, because romanization of Korean is very variable and confusing at times. Please take a couple of hours in your first week to fully master reading and writing the script before you continue learning. It will help you a lot!!

Together with this you’ll want to work on pronunciation. Don’t worry or feel bad when it doesn’t sound well the first few times. Just keep trying. I recommend listening (see a little further down for some resources): pausing after sentences and repeating them. Imitation after all is one of the most important ways in which a human learns!

When it comes to theory, I think it’s best to follow online courses or buy textbooks that fit to your way of learning. You can also learn from separate resources but generally books/websites have a set order in which you learn things - and these orders are there because you need to know certain things before you can understand other things, so I recommend you just follow a series of lessons.

Online Theory Resources

I personally use the website howtostudykorean.com. It is completely free (except for the PDF files and exercise books, which go for a couple dollars a piece - which is still cheap AF tbh) and I really like the way and extend in which concepts are explained. The concepts are explained in such a way that you always understand WHY a piece of grammar works in the way it does, which I think is one of its strong points. I strongly recommend this website for learning Korean and I personally feel like this site as pretty much everything you need to get a good theoretical grasp. It starts on complete beginner level and extends out to hanja lessons even, so 10/10 points to them.

I have also tried Talk To Me In Korean (TTMIK) which seems to be really popular amongst most Korean learners but personally, I think the concepts aren’t explained very thoroughly and the way they explain the material makes me feel like a small child. BUT I am really positive about their YouTube channel so make sure to check that out!

Talking about YouTube, there are loads of interesting channels that can help you out! Some of my personal favorites are the TTMIK channel and the ever-sweet and funny Korean Unnie!

I think these are the most popular websites for learning Korean and I am about 99,99% sure that you won't need any textbooks if you use these, really.

Tumblr is also a really nice source of vocabulary lists andpeer-teached grammar lessons, and there is also a nice amount ofcultural lessons if you search good enough. Do pay attention though,because these types of materials are more likely to contain mistakesor typos. Besides that Tumblr is a really nice community to come intocontact with lots of other (Korean) language learners!

So. Besides getting your share of theory you will need practice. Especially if you don't live amongst Koreans (which I assume you don't) you will need to fill that up. How do we do that?

Listening

For practicing listening there are a couple things you can do.

Listen to Korean radio and/or K-pop

Korean radio is a good source of naturally occuring speech. Make sure you put on a station that has a DJ that talks (some stations just play music). You get commentary, interviews, conversations and as a bonus you get to listen to Korean music.

Korean listening exercises

You can find plenty of listening exercises on YouTube. Maybe give these a try:

- Korean Class 101

- TTMIK Listening in Slow Korean series

- TTMIK IYAGI - Natural Conversations in 100% Korean

Korean videos/TV/dramas

The internet offers access to loads of Korean video material. You can check out Korean TV programs (Running Man is very popular) or dramas (try Viki.com). Another way I like to incorporate listening practice into my learning is by watching Korean youtubers. The more popular channels are likely to have both English and Korean subs so that might help you out.

Speaking

The best way to learn to speak Korean naturally, fast is of course to talk to Korean speakers. Finding someone to chat with if you have no Korean friends can be somewhat of a challenge. My university organizes monthly 'language cafe's' that bring together students who are learning another language. Try searching for something similar in your own neighborhood. If you really can come into contact with native speakers, I recommend trying apps such as HelloTalk. I personally really like this app and have already earned a new friends because of it. It allows users to come into contact with others who are learning another language, and are willing to teach their own language to others. It is chat based but if you want to, you can also send voice messages or call.

Reading

As someone who doesn't have English as a first language, I canconfirm that reading is one of the best ways to gain proficiency in alanguage. It provides you with lots of vocabulary and makes youfamiliar with sentence structure, grammatical rules and more. Trystarting with simple texts such as children's books and slowly try towork your way up to news articles, short texts and ultimately actual(simple) books. A simple google search quiry will get you to loads ofKorean news pages and downloadable kids' books.

Other tools I use

Website: Naver English Dictionary

Basically the holy grail for Korean language learners. Gives you excellent detailed definitions and translations for both korean-english and english-korean. It also provides you with tons of example sentences, common word combinations, and my personal favorite: V-LIVE subtitles that have the word you searched in them. This function is AMAZING because you get to see how a certain word is being used in real, actual conversations. You can even click a link to go to the original video so you can hear the pronunciation and the context (conversation) in which it was used. Actual gold.

App: Rieul Korean (Android)

My go-to dictionary app. Has a link to four different online dictionaries (DAUM English, Naver English, DAUM Korean and Naver Korean), a vocab lookup section with hanja testing function, a conjugation section, pronunciation section, numbers section and a section on Korean idioms.

App: K'way and Grammar Haja (Android)

Both apps that explain grammar theory. Not recommended for learning but very handy to have as a reference.

App: TOPIK ONE (android)

Lets you take a fake version of the TOPIK I exam. Gives simple feedback. Very handy to keep track of your progress and to practice for the TOPIK exam if you plan to take that.

App: 라디오 한국 FM (Radio Hanguk) (android)

Just a very simple app with a list of Korean radio stations. I like listening to NCT Night Night on SBS Power FM!

These printable handwriting sheets - for giving your handwriting a fancy boost

Tips & Tricks

I like to set devices and applications to Korean to get some more exposure to the language. You can set sites like Google to Korean. The nice thing about this is that you learn new words that are used mostly online such as “닫기” (close) and “구독” (subscribe).

Try keeping a language journal. It is a fun way to bring your knowledge in to practice. I am actually making a post on that right now so keep an eye on my blog if you want to read it!

Get a study buddy. Nothing motivates better than a healthy dose of mutual support and a slight dose of pressure, hehe.

Study regularly, daily if you can. Even if it’s just half an hour a day, try to keep your study sessions consistant. Adapt the amount of time you put into the language based on your schedule and the goals you want to achieve. Want to keep up a decent conversation within a year? Plan on at least 8 hours a week.

Posts by others

List of free Korean resources by @onestopkorean

Nice lil’ list of resources by @elkstudies

I probably forgot to mention a TON of stuff but I hope this will help you on your way~! Lots of success and happy studying! 열심히 공부 하자!

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top Dead and Constructed Languages to Learn

Top Dead and Constructed Languages to Learn - Sciforce - Medium

As a rule, when we choose a language to learn, we have several reasons in mind: they might be useful for our professional growth or helpful in travels or in communication with certain communities. We might need a language because we move to another country or because we fall in love with a foreigner. However, a new language can be not only a means of communication: it is also a way to sharpen your mind, to find a deeper mental structure in what might first seem to be verbal chaos — and ultimately it can become a proxy to mastering computer logic and machine learning.

That is why it is a good idea to learn not a real live language — but a tongue that is dead and reconstructed or completely invented. Striped of numerous exceptions, variations and usage simplification that are inherent to natural languages we speak, they show only the ideal logical structure in the core of any language — be it human, computer, or mathematical.

In this blog post, we’ll present a list of our top of dead and artificial languages that might be useful to learn.

Dead Languages

Latin

Much more than a dead language of a dead ancient Empire, Latin is the language that had an enormous impact on the development of other European languages, as well as on the European culture and science.

Why to learn?

Latin is the parent of the modern Romance languages, which include Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese and others. Therefore, the knowledge of Latin can facilitate learning these languages — and train you to see and to use the connections and similarities between them. These connections are so huge that learning Latin will virtually open up access to the whole Romance language family — and boost your analytical skills.

Latin is a highly-inflected language, which means that you can alter the meanings of words by merely changing the ending suffice. On the one hand, it makes Latin difficult to learn; on the other hand, it gives you an idea of the power of minute changes and a good eye for detail. And you’ll see that Latin IS well-structured!

Latin is not so dead as we might think. It is used, of course, in Catholic Church, but, more importantly, it is the basis of medical and biological classifications and to a certain extent of the academic slang.

Where to learn?

Latin might be offered to you at your university (it might be also a compulsory course), so grab the chance!

There are of course numerous courses and learning resources for any level:

Getting started on classical Latin is a free course that is aimed not at mastering the language itself but rather at discovering Latin grammar structures and its impact on English.

Learn Latin is a free app that provides users with vocabulary (verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs) that they can easily use to learn a word a day. Example sentences will also be provided to help learn the new word.

New Latin Grammar — a textbook for those who like explicit explanations.

unsplash.com

Sanskrit

Similar to Latin in Europe, Sanskrit was the lingua franca of the Indian subcontinent for three millennia and it provided the foundational texts for Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism.

Why to learn?

Sanskrit has a huge impact on modern Indo-Aryan languages, such as Hindi that directly borrows Sanskrit grammar and vocabulary. Its influence reaches other languages, including Austronesian, Sino-Tibetan, and the languages of Southeast Asia.

The 49-character alphabet arranges characters in a rational and systematic manner: both the vowels and consonants are arranged according to the shape of the mouth when these sounds are emitted.

The morphology of word formation is unique and of its own kind where a word is formed from a tiny seed root in a precise grammatical order which has been the same since the very beginning. Any number of new words could be created from the root with the help of an extremely detailed prefix and suffix system.

The current global interest in Sanskrit is connected with the spread of yoga practices and Indian way of life around the world, so it has become a trendy language among people who declare to live “clean”.

Where to learn?

Learn Sanskrit online — an online course for beginners that features a rather informal approach to learning a new language.

Sanskrit grammar — in case you don’t want to actually speak Sanskrit but would prefer to use it as a tool to train your mind.

Ancient Greek

Classical, or Ancient, Greek is often considered the most important language in the intellectual life of Western civilization. While it does use an older and more foreign alphabet, learning Ancient Greek can allow you to read many ancient intellectual texts.

Why to learn?

Though not as evident as Latin, Greek has traces in modern academic languages: for instance, many of the modern English names of scientific disciplines come from Ancient Greek, including psychology, philology, theology, philosophy, etc.

The Greek alphabet was taken over from the Semitic as used in the Phoenician area, which in turn was based on an Egyptian alphabet. That makes the Greek alphabet a link between Western alphabets and the morphology of alphabets across Asia. Being familiar with the Greek alphabet is a definite advantage: even now, many technical studies borrow from the Greek alphabet and use it to a considerable degree.

Learning Ancient Greek can improve your understanding of grammar, since the sentence structure and the number of forms require a great deal of attention. The words of sentences are placed for their emphasis, rather than in accordance with a specific pattern, making the knowledge of the inflections highly important. Besides, inflections are attributes not only of nouns, but also of adjectives, pronouns, verbs and articles, so you need to keep an eye on all parts of speech simultaneously.

Where to learn?

Learn Ancient Greek is a free online course to learn the fundamentals of Classical Greek.

Introduction to Ancient Greek — is a traditional textbook that provides a thorough explanation of Ancient Greek grammar and morphology.

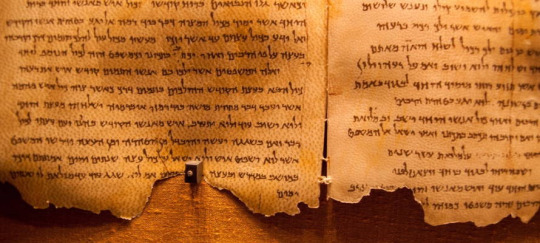

Hebrew

unitedwithisrael.org

Biblical Hebrew is the archaic form of modern Hebrew used to write the Old Testament of the Bible. Developed into a literary and liturgical language around 200 CE, it is currently taught in public schools in Israel, as an important way to understand modern Hebrew and the Jewish faith.

Why to learn?

It’s a very popular language for Jewish and Christian followers to study because it opens up the possibility for reading the Old Testament in its original language.

While it is similar to Modern Hebrew, the style, grammar, and vocabulary of Biblical Hebrew makes it much more difficult to learn. Having to establish the precise use of a case or mood or voice makes the interpreter consider all the various possibilities of meaning inherent in the language of the text. It sounds overcomplicated, but it is a perfect workout for your brains and the ability to consider all possibilities is a definite advantage.

Hebrew alphabet is also notoriously difficult to learn: in its traditional form, it consists only of consonants, written from right to left. It has 22 letters, five of which use different forms at the end of a word. Vowels are indicated by the weak consonants serving as vowel letters, or the letter can be combined with a previous vowel and becomes silent, or by imitation of such cases in the spelling of other forms. Bottom line, Biblical Hebrew is for those who like puzzles and mysteries hidden from the plain view.

Where to learn?

Biblical Hebrew Grammar — a course of 50 lessons covering the fundamentals of Ancient Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew — a set of online courses for different levels from absolute beginners to expert learners.

Old English

thoughtco.com

Old English, sometimes referred to as Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest historical form and the forefather of the contemporary English language. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers probably in the mid-5th century and was spoken in England and Southern and Eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages.

Why to learn?

Spoken in England before the Norman Conquest, Old English remains a truly Germanic language and shows the modern English connections to the Germanic family.

By learning Old English you can trace the evolution of a language over centuries on all levels from phonetic shifts to simplification of grammar and changes in vocabulary. This makes evident how a language responds to the changes in the society and how complicated grammar used to be.

Besides, it is written in the Anglo-Saxon variant of runes, so you can pretend to be a Viking.

Where to learn?

Old English Online is a course offered by the University of Texas where you will read through ancient texts building up your knowledge of Old English gradually.

Leornende Eald Englisc is a YouTube channel for those who likes less traditional and relaxed learning process.

Constructed Languages

Esperanto

Esperanto is the most successful international auxiliary language, with up to two million speakers. It was invented in the late 19th century by a Polish doctor, Ludwik Zamenhof, who wanted to end interethnic conflicts by providing everyone with a common and politically neutral tongue.

www.078.com.ua

Why to learn?

Contrary to old and dead languages, invented languages tend to simplify grammar and morphology. In Esperanto, word roots are mostly based on Latin and can be combined with affixes to form new words. The affixes can also stand alone: ejo = place, estro = leader/head, etc. The grammar has many traces of Slavic languages, although it is greatly simplified in comparison to them.

Spelling conventions are somewhat similar to Polish, though Zamenhof came up with some new letters for Esperanto (Ĉĉ, Ĝĝ, Ĥĥ, Ĵĵ, Ŝŝ, Ŭŭ). These letters are often replaced with ch, gh, jh or cx, gx, jx, or c’, g’, j’, etc.

Esperanto is an easy language to master with its small set of grammar rules and a transparent system of word endings: -o for nouns, -a for adjectives, -e for adverbs, -as for verbs in present tense. This makes grammar much clearer to a novice in language learning.

Where to learn?

Esperanto course– an app to learn basic Esperanto

Free Esperanto Course — a somewhat more traditional course explaining grammar rules and vocabulary.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toki_Pona#/media/File:Sitelen_sitelen_contract.jpg

Toki Pona

Toki Pona is a language created by the Canadian linguist and translator Sonja Lang as a philosophical language for the purpose of simplifying thoughts and communication.

Why to learn?

Lang designed Toki Pona to express maximal meaning with minimal complexity and to promote positive thinking. One of Toki Pona’s main goals is a focus on minimalism, as it focuses on simple concepts and universal elements. The language has 120–125 root words and 14 phonemes designed to be easy to pronounce for speakers of various language backgrounds. Therefore, learning this language can help switch the focus from complexity to the minimum repertoire.

Inspired by Taoist philosophy, the language is designed to help users remove complexity from the thought process. Even with the small vocabulary, speakers are able to communicate, mainly relying on context, which highlights the importance of non-linguistic means of communication.

Where to learn?

o kama sona e toki pona! — a Toki Pona course introducing grammar rules and vocabulary

speak toki pona — an introductory audio course

Klingon

https://daily-klingon.tumblr.com/post/179493082615/this-is-the-piqad-script-as-developed-by-michael

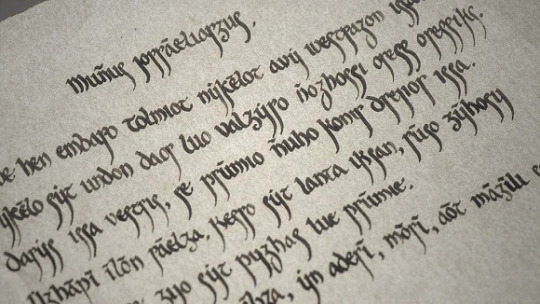

Klingon, the language of a fictional warrior alien race in the Star Trek created by Marc Okrand and it is maybe the most famous constructed language.

Why to learn?

Perhaps the most fully realized science fiction language, Klingon has a complete grammar and vocabulary of 3000 words, so fans can actually learn it. There are even translations of Shakespeare, Sun Tzu and the Bible into the language.

Klingon was mostly created by a linguist who deliberately added complex rules and sounds that are rare in human languages. Therefore, this language, though not fully natural, can serve us as a proxy to understanding an alien — or at least a foreign — way of thinking and conceptualizing the world.

Another possible difficulty for anyone wanting to communicate in Klingon is that, as a space-based language, it’s lacking a lot of normal Earth words.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K0cFLb-JmaQ Star Trek: Into Darkness

Where to learn?

There’s a Klingon Language Institute, the purpose of which is to promote the language and culture of this nonexistent people.

Learn Klingon the Easy(ish) Way — an online course of Klingon on You Tube

Learn Klingon Online — a complete course of Klingon

Quenya

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fictional_language

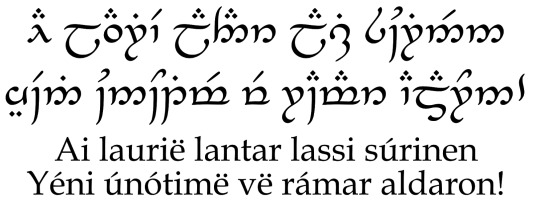

Quenya is one of the languages invented by JRR Tolkien in his Middle-earth world. A ceremonial Elvish tongue, it’s the most elaborate of all of Tolkien’s languages.

Why to learn?

First of all, Middle Earth was invented for Quenya and not vice versa: Tolkien began to write his stories in order to provide his language with a historical background. Tolkien tried to create the most beautiful language imaginable, and the sounds and grammar were taken mostly from the real Earth languages that he thought were the most beautiful: Finnish, Latin and Greek.

The most striking feature of Quenya is that it is a highly agglutinating language, meaning that multiple affixes are often added to words to express grammatical function. It is possible for one Quenya word to have the same meaning as an entire English sentence. Therefore, Quenya helps master a completely different way of building sentences and shows the possibilities of language economy.

It uses a special set of Elfish runes featuring, among others, representation of vowels with diacritics and the correspondence between shape features and sound features, and of the actual letter shapes.

https://www.looper.com/34326/things-you-didnt-know-about-the-ring-in-lord-of-the-rings/

Lord of the Rings (yes, we know that it’s the Black speech written in Tengwar)

Where to learn?

Quenya course — a textbook explaining Elfish grammar and introducing vocabulary.

Quenya — the Ancient Tongue — a brief survey providing the basics of Quenya grammar

High Valyrian

https://gameofthrones.fandom.com/wiki/High_Valyrian

High Valyrian is a ceremonial language from A Song of Ice and Fire series of fantasy novels by George R. R. Martin. While High Valyrian is not developed beyond a few words in the novels, for the TV series, linguist David J. Peterson created both the High Valyrian language, and its derivative languages Astapori and Meereenese Valyrian.

Why to learn?

This is the most recently developed language for the most popular TV series, so learning it at present is timely and trendy.

A dead language in the world of Westeros, High Valyrian occupies a cultural niche similar to that of Latin being the language of learning and education among the nobility, so learning it can make you feel double sophisticated (or nerd).

Despite its complicated inflectional grammar, High Valyrian does not have a special alphabet, so it is easier to master reading from the very beginning without additional obstacles.

https://gameofthrones.fandom.com/ru/wiki/%D0%9A%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%81%D0%BD%D1%8B%D0%B5_%D0%B6%D1%80%D0%B5%D1%86%D1%8B?file=%D0%9C%D0%B5%D0%BB%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%80%D0%B0_5x01.jpg

Where to learn?

High Valyrian Course — an app teaching the basic vocabulary and phrases

Learning High Valyrian — resources on grammar, phonology and vocabulary developed by fans

It might be that constructed languages lack the depth as they do not have actual system of idioms and metaphors behind them, or that dead languages are overcomplicated and outdated and no one would be able to communicate in them at present. However, learning such languages is an excellent exercise for our mind that help us develop more focus and attention and understand more about the logic of a language, the way we shape it and the way we want artificial languages — including machine ones — to work.

1 note

·

View note