#textiles of india

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Muslin, that diaphanous cotton of India, is steeped in a bleak history of colonialism, Imperialism, and human atrocity. That's a way to start a Monday, isn't it? But that's the thing about fashion history.

Looking at a gown like this, which dates from the late 1840s, it's easy to get lost in the beauty: the pattern, the layers, the absolute Romantic gorgeousness.

It is, undoubtedly, a work of art, making use of that thin, breathable fabric, with delicate ruching, a genius use of pattern, and a shape that's reminiscent of the 18th century.

The demand for muslin fabric was immense, bolstered by the impact of the British East India Company, beginning in the 18th century. The finest muslins were from the Dhaka region and 2000 thread count *made by hand*. Starting with Marie Antoinette and her famous chemise a la reine, the craze for muslin among the elites of Europe came at a devastating cost--eventually contributing to the loss of the art and the death of millions of people in the regions.

Because once Europeans figured out how to manufacture muslin on their own (as they did with silk, paisley, pashminas, etc) they stopped all trade with India.

And of course, the great irony is that Europeans didn't just take the art and design, but directly appropriated patterns, styles, and more. There's a reason "question beauty relentlessly" is the Thread Talk motto. Lots more info on the subject over at my blog.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

#threadtalk#historical costuming#silk dress#textiles#fashion history#costume#costume history#history of fashion#muslin#textiles of india

625 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weavers showcasing their intricately handwoven work, Kashmir, 1961 by Slim Aarons

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ikkat is a traditional textile printing technique originating from India and Southeast Asia. It's known for its unique, blurred, and feathered patterns. The word ikat is derived from the Malay word mengikat, which means to tie or bind. The ikkat fabric is created by tying the threads in a specific pattern and then dyeing them in various colors. Once the threads are dyed, they are woven into patterns and designs. Ikkat patterns have soft, blurred edges due to the resist-dyeing process, and often feature feathered or cloud-like designs, which are achieved by binding and dyeing the fabric. Ikkat prints typically feature geometric patterns, such as stripes, dots, and chevrons dyed in vibrant and bold colors. Ikkat print is used in various textiles, such as scarves, saris, dress materials, and home decor fabrics.

1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 | textile series

#textiles#textile history#southeast asia#south asia#india#indian textiles#south asian textiles#fashion#fashion history#desi fashion#desi tumblr#desiblr#ikkat#ikkat print#ots

371 notes

·

View notes

Text

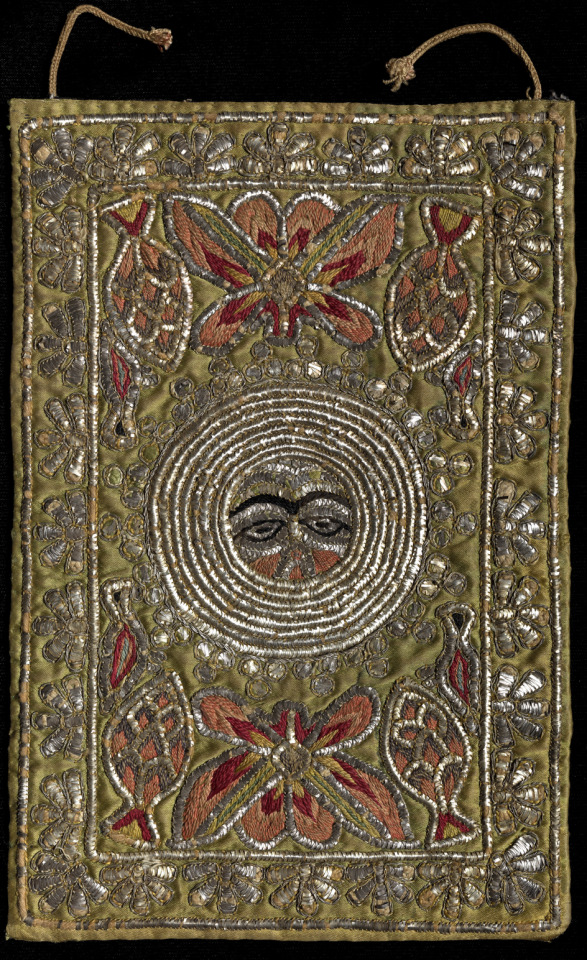

embroidered textile, silk gold and silver thread on satin, india, 1800s.

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fragment of a floor cover (India, Mughal dynasty, late 17th or early 18th century).

Painted and dyed cotton.

Image and text information courtesy MFA Boston.

337 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yesterday at Textile Research Centre Leiden: Mirror embroidery from India, Pakistan, Afghanistan.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hanging (Qalamkar)

India or Iran, 1920 - 1960

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ceremonial cloth with mata hari (‘eye of the day’) design, 18th or 19th century, Coromandel Coast, India, dyes and mordants on cotton.

270 x 240 cm

Apollo Magazine / Collection of Karun Thakar

606 notes

·

View notes

Text

Man's hunting coat of embroidered satin with silk, India, ca. 1610-1630

This splendid coat was made for a man at the Mughal court in the first half of the 17th century. It is embroidered in fine chain stitch on a white satin ground, with images of flowers, trees, peacocks, wild cats and deer. The area around the neck is left free of embroidery, as a separate collar or tippet, probably of fur, would have been attached. Chain-stitch embroidery of this type is associated with professional, male embroiderers of Gujarat, where they were employed to embroider fine hangings and garments for the Mughal court, as well as for export to the West.

via Victoria & Albert Museum

#history#historical fashion#fashion history#mughal empire#17th century#textile#embroidery#silk#hunting coat#floral#nature#chain-stitch#mughal#india#indian art#posted art

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

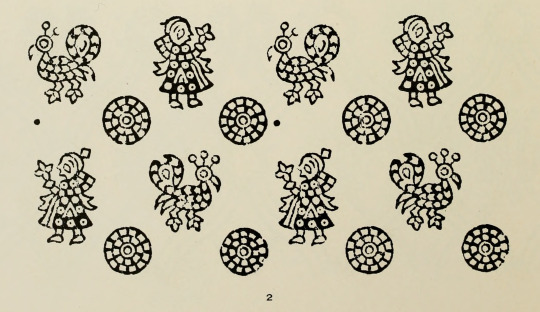

Textile pattern. Block prints from India for textiles. 1924.

Internet Archive

289 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The art of the textile label: a Bengaluru exhibition at MAP

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

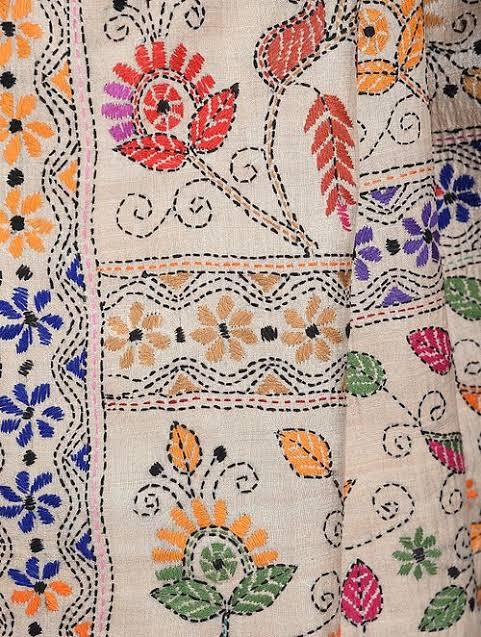

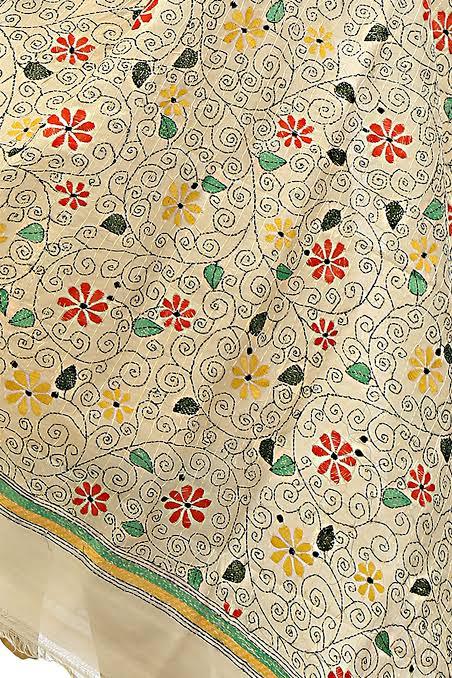

Kantha (Bengali: কাঁথা) is a form of embroidery originating in Bengal region, i.e. Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and parts of Assam. It has its roots in nakshi kantha, an ancient practice among bengali women of making quilts from old saris and rags by sewing them together. In modern usage, kantha generally refers to the specific type of stitch used. The kantha needlework is distinct and recognised for its delicacy. The stitching on the cloth gives it a slightly wrinkled, wavy effect. Today, kantha embroidery can be found on all types of garments as well as household items like pillowcases, bags and cushions.

While it is an increasingly diversifying art form, traditional kantha embroidery motifs are still sought after. Traditional kantha embroidery is two-dimensional and are usually of two distinct types: geometric forms with a central focal point, carried over from the nakshi kantha tradition and influenced by islamic art forms; and more fluid plant, floral, animal and rural motifs with stick-figure humans depicting folklores and rural life in Bengal.

1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 / 7 / 8 / 9 | textile series

#bangla tag#textiles#ots#kantha#nakshi kantha#bengal#bengali#bangladesh#india#embroidery#needlework#textile art#embroidery art#south asia#south asian

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sonam Kapoor wearing a bridal outfit by Rohit Bal at India Bridal Fashion Week 2013.

youtube

#RIP#Rohit Bal#fashion#bridalwear#wedding dress#bridal fashion#indian fashion#indian bride#sonam kapoor#2013#indian bridal fashion week#pattern#surface pattern#surface pattern design#pattern design#textile design#textiles#lehenga#runway#india bridal fashion week

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

[T]he Dutch Republic, like its successor the Kingdom of the Netherlands, [...] throughout the early modern period had an advanced maritime [trading, exports] and (financial) service [banking, insurance] sector. Moreover, Dutch involvement in Atlantic slavery stretched over two and a half centuries. [...] Carefully estimating the scope of all the activities involved in moving, processing and retailing the goods derived from the forced labour performed by the enslaved in the Atlantic world [...] [shows] more clearly in what ways the gains from slavery percolated through the Dutch economy. [...] [This web] connected them [...] to the enslaved in Suriname and other Dutch colonies, as well as in non-Dutch colonies such as Saint Domingue [Haiti], which was one of the main suppliers of slave-produced goods to the Dutch economy until the enslaved revolted in 1791 and brought an end to the trade. [...] A significant part of the eighteenth-century Dutch elite was actively engaged in financing, insuring, organising and enabling the slave system, and drew much wealth from it. [...] [A] staggering 19% (expressed in value) of the Dutch Republic's trade in 1770 consisted of Atlantic slave-produced goods such as sugar, coffee, or indigo [...].

---

One point that deserves considerable emphasis is that [this slave-based Dutch wealth] [...] did not just depend on the increasing output of the Dutch Atlantic slave colonies. By 1770, the Dutch imported over fl.8 million worth of sugar and coffee from French ports. [...] [T]hese [...] routes successfully linked the Dutch trade sector to the massive expansion of slavery in Saint Domingue [the French colony of Haiti], which continued until the early 1790s when the revolution of the enslaved on the French part of that island ended slavery.

Before that time, Dutch sugar mills processed tens of millions of pounds of sugar from the French Caribbean, which were then exported over the Rhine and through the Sound to the German and Eastern European ‘slavery hinterlands’.

---

Coffee and indigo flowed through the Dutch Republic via the same trans-imperial routes, while the Dutch also imported tobacco produced by slaves in the British colonies, [and] gold and tobacco produced [by slaves] in Brazil [...]. The value of all the different components of slave-based trade combined amounted to a sum of fl.57.3 million, more than 23% of all the Dutch trade in 1770. [...] However, trade statistics alone cannot answer the question about the weight of this sector within the economy. [...] 1770 was a peak year for the issuing of new plantation loans [...] [T]he main processing industry that was fully based on slave-produced goods was the Holland-based sugar industry [...]. It has been estimated that in 1770 Amsterdam alone housed 110 refineries, out of a total of 150 refineries in the province of Holland. These processed approximately 50 million pounds of raw sugar per year, employing over 4,000 workers. [...] [I]n the four decades from 1738 to 1779, the slave-based contribution to GDP alone grew by fl.20.5 million, thus contributing almost 40% of all growth generated in the economy of Holland in this period. [...]

---

These [slave-based Dutch commodity] chains ran from [the plantation itself, through maritime trade, through commodity processing sites like sugar refineries, through export of these goods] [...] and from there to European metropoles and hinterlands that in the eighteenth century became mass consumers of slave-produced goods such as sugar and coffee. These chains tied the Dutch economy to slave-based production in Suriname and other Dutch colonies, but also to the plantation complexes of other European powers, most crucially the French in Saint Domingue [Haiti], as the Dutch became major importers and processers of French coffee and sugar that they then redistributed to Northern and Central Europe. [...]

The explosive growth of production on slave plantations in the Dutch Guianas, combined with the international boom in coffee and sugar consumption, ensured that consistently high proportions (19% in 1770) of commodities entering and exiting Dutch harbors were produced on Atlantic slave plantations. [...] The Dutch economy profited from this Atlantic boom both as direct supplier of slave-produced goods [from slave plantations in the Dutch Guianas, from Dutch processing of sugar from slave plantations in French Haiti] and as intermediary [physically exporting sugar and coffee] between the Atlantic slave complexes of other European powers and the Northern and Central European hinterland.

---

Text above by: Pepijn Brandon and Ulbe Bosma. "Slavery and the Dutch economy, 1750-1800". Slavery & Abolition Volume 42, Issue 1. 2021. [Text within brackets added by me for clarity. Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#abolition#these authors lead by pointing out there is general lack of discussion on which metrics or data to use to demonstrate#extent of slaverys contribution to dutch metropolitan wealth when compared to extensive research#on how british slavery profits established infrastructure textiles banking and industrialisation at home domestically in england#so that rather than only considering direct blatant dutch slavery in guiana caribbean etc must also look at metropolitan business in europe#in this same issue another similar article looks at specifically dutch exporting of slave based coffee#and the previously unheralded importance of the dutch export businesses to establishing coffee mass consumption in europe#via shipment to germany#which ties the expansion of french haiti slavery to dutch businesses acting as intermediary by popularizing coffee in europe#which invokes the concept mentioned here as slavery hinterlands#and this just atlantic lets not forget dutch wealth from east india company and cinnamon and srilanka etc#and then in following decades the immense dutch wealth and power in java#tidalectics#caribbean#archipelagic thinking#carceral geography#ecologies#intimacies of four continents#indigenous#sacrifice zones#slavery hinterlands#european coffee#indigenous pedagogies#black methodologies

26 notes

·

View notes