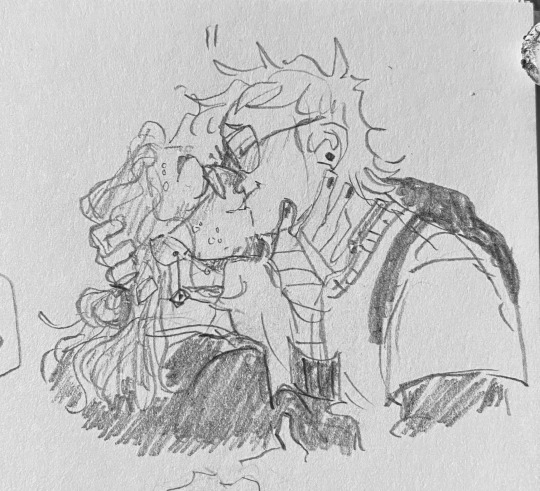

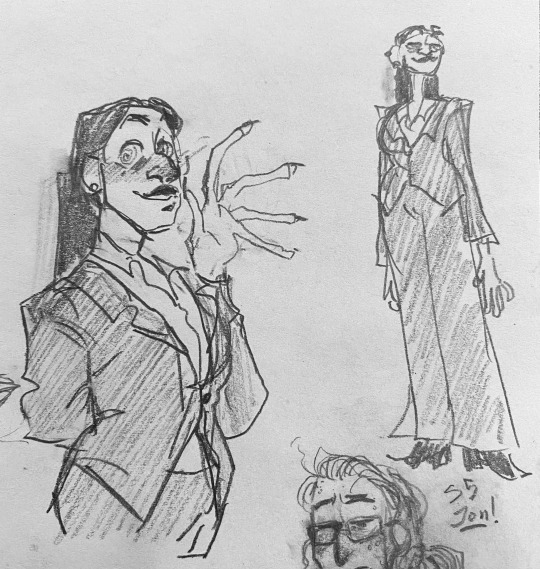

#tbh I wasn’t vibing with Martin at first but now he’s my silly guy I love him

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I love gay people 🫶🫶

#JON N MARTIN MY BELOVEDSSS#tbh I wasn’t vibing with Martin at first but now he’s my silly guy I love him#artists on tumblr#the magnus archives#the magnus archive fanart#tma#tma fanart#jmart#jonmartin#jmart fanart#jon sims#jonathan sims#martin blackwood#oliver banks#mike crew#terminal velocity#helen distortion#mag 168

7K notes

·

View notes