#suzuri kai

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Mikoto with Minamo and Suzuri!

Now that the Kai Sister designs have been found I'll try to draw them all at some point.

🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍🐍

Bluesky

Instagram

DeviantArt

Patreon

Twitch

#touhou#marine benefit#touhou kaikeidou#touhou project#mikoto yaobi#minamo kai#suzuri kai#servants of the feast#touhou fangame#touhou fanon#my art#art#fan art

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yume boundaries F / O list

⭕ = it's okay If you want to sharing with me

✅ = I'm will accepted if you being nice with me

⁉️ = new Yume debut announcement

❎ = i don't feel comfortable to talking about when drama related

❌ = sorry no sharing i don't have friends related

Platonic

Harvard Marks (Decapolice) ❌

Ban Van Yamano (Danball Senki) ❌

Prince Kaiser (Duel Master Win) ❌

Sawyer Haru Tomura (Tosochu Great Mission) ❌

Morris Shoemakers (Tosochu Great Mission) ❌

Ixa (Otome Yuusha) ⭕

Veloute (The Snack World) ⭕

Zwijo (Yugioh Go Rush) ⭕

Wisdom (Buddyfight) ❌

Suruga Yagyu / Thierry Reyes (Inazuma Eleven Victory road) ⭕

Tsubasa Akai (Kaitou Joker) ❌

Matsunosuke Agata (Ride Kamens) ⭕

Kaito Gosho (Hero Bank) ❌

Yuujin Ozora (Digimon Universe Appli monsters) ❌

Narushi Kamui (Ride Kamens) ⭕

Nagare Amano (Hero Bank) ❌

Sekito Sakuraba (Hero Bank) ❌

Optimus Prime (Transformers) ⭕

Wataru Hoshibe (Mashin Creator Wataru) ❌

Kota Koka (Cap Revolution Bottleman dx) ❌

Eiji Nagasumi (Digimon Seekers) ❌

Q (Tribe Nine) ✅

Yo Kuronaka (Tribe Nine) ✅

Kazuki Aoyaka (Tribe Nine) ✅

Jio Takinogawa (Tribe Nine) ✅

Medicine Pocket (Reverse 1999) ⭕

A Knight (Reverse 1999) ⭕

Druvis iii (Reverse 1999) ⭕

Eternity (Reverse 1999) ⭕

Ms NewBabel (Reverse 1999) ⭕

Xavier (Love and Deepspace) ✅

Zayne (Love and Deepspace) ✅

Caleb (Love and Deepspace) ✅

Calcharo (Wuthering Waves) ❎

Xiangli Yao (Wuthering Waves) ❎

Lingyang (Wuthering Waves) ❎

Aalto (Wuthering Waves) ❎

Mortefi (Wuthering Waves) ❎

Kuaidul Velgear (Yugioh Go Rush) ❌

Yuki Tendo (Buddyfight) ❌

Satoshi Tsukimura (Tosochu Great Mission) ❌

Shouta Soramine (Buddyfight) ❌

Kezuru (Mazica Party) ❌

Kobirabi Cookie (Cookie run tower of adventure) ⭕

Takashi Taiga (Puzzdra) ❌

Ace (Pazudora Cross) ❌

Cache (Rich Police Cash) ❌

Shun Kazami (Bakugan battle planet) ❌

Rei Katsura (Digimon Universe Appli monsters) ❌

Hayato Hayasugi (Shinkalion Animation) ❌

Shin Arata (Shinkalion Z Animation) ❌

Romantic

Carl Oxford (Decapolice) ❌

Hideto Suzuri (BattleSpirits) ❌

Daiki Dak Sendou (Danball Senki) ❌

Sigma Redwing (Tosochu Great Mission) ❌

Yukinojo (Tosochu Great Mission) ❌

Gakuto Gavin Sogetsu (Yugioh Sevens) ⭕

Grimoire (Buddyfight) ❌

Kirameki Sasuga (Yo-kai Watch Jam) ⭕

Garyu Shisendo / Alix La Fontaine (Inazuma Eleven Victory road) ⭕

Chrono (Space Time Police / Rewinder of Fate) ❌

Haru Shinkai (Digimon Universe Appli monsters) ❌

Knight Unryuji (Digimon Universe Appli monsters) ❌

Kyosuke Araki (Ride Kamens) ⭕

Eplison (Pluto) ❌

Kakeru Amabe (Mashin Creator Wataru) ❌

Ryo Hokari (Cap Revolution Bottleman dx) ❌

Sui Yakumo (Tribe Nine) ✅

Zero (Tribe Nine) ✅

Shun Kamiya (Tribe Nine) ✅

Kazuma Ichinose (Tribe Nine) ✅

Yutaka Gotanda (Tribe Nine) ✅

Koishi Kohinata (Tribe Nine) ✅

Hyakuichitaro Senju (Tribe Nine) ✅

X (Reverse 1999) ⭕

Shamane (Reverse 1999) ⭕

Mercuria (Reverse 1999) ⭕

Yoyager (Reverse 1999) ⭕

Mr Duncan (Reverse 1999) ⭕

Horrorpedia (Reverse 1999) ⭕

Rafayel (Love and Deepspace) ✅

Sylus (Love and Deepspace) ✅

Brant (Wuthering Waves) ❎

Jiyan (Wuthering Waves) ❎

Yuanwu (Wuthering Waves) ❎

Male / Female Rover (Wuthering Waves) ❎

Makoto Tsukimiya (Buddyfight) ❌

Yuo Goha (Yugioh Sevens) ❌

Silver (Mazica Party) ❌

Masato Kazami (Bakugan battle planet) ❌

Ryuji Matsubara (Puzzdra) ❌

Lance (Pazudora Cross) ❌

J Genesis (Buddyfight) ❌

Seiryu (Shinkalion Animation) ❌

Abuto Usui (Shinkalion Z Animation) ❌

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

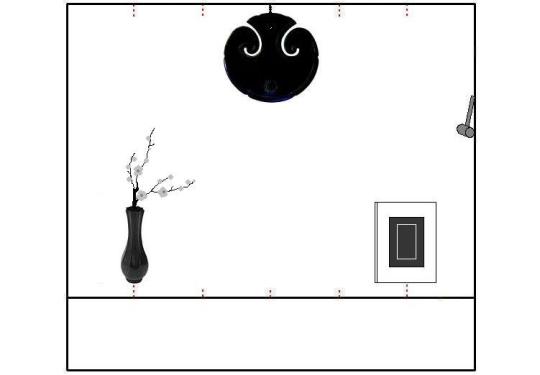

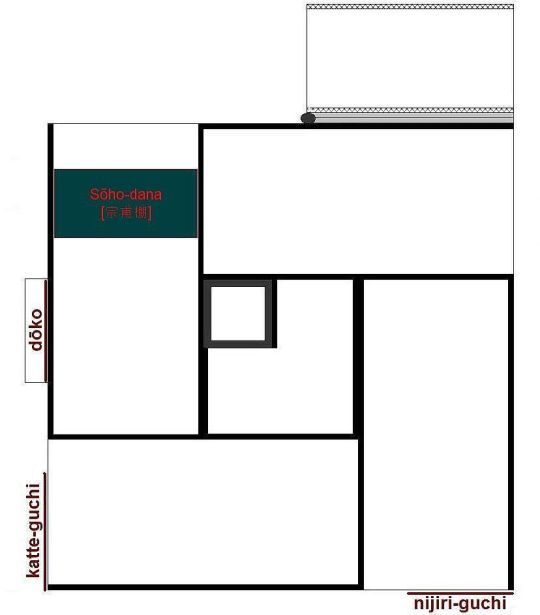

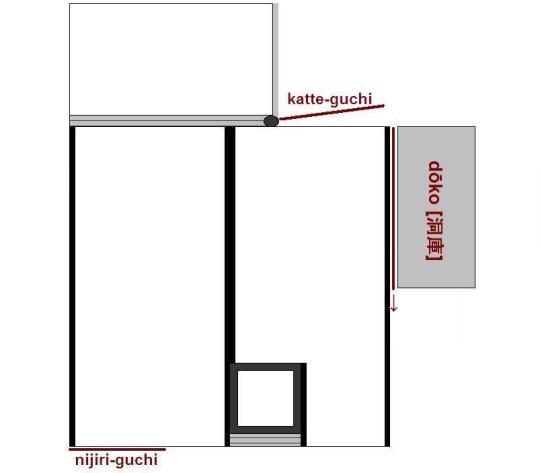

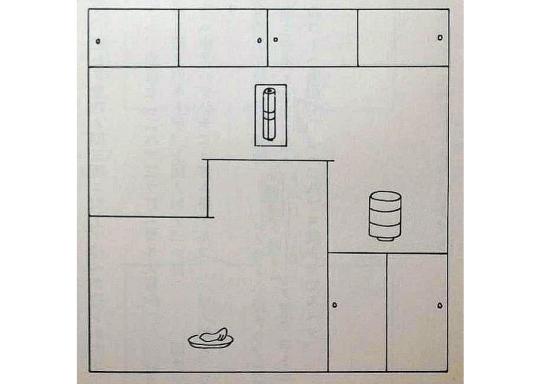

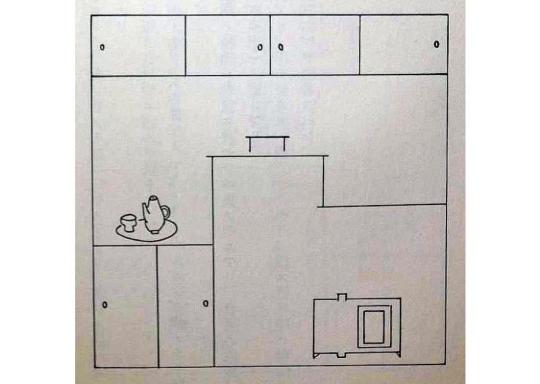

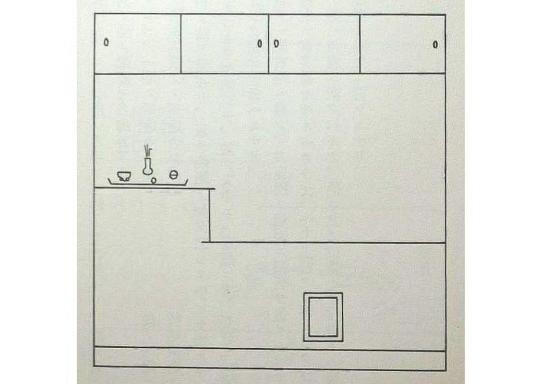

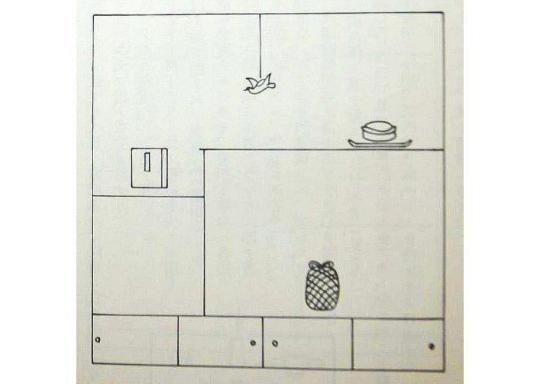

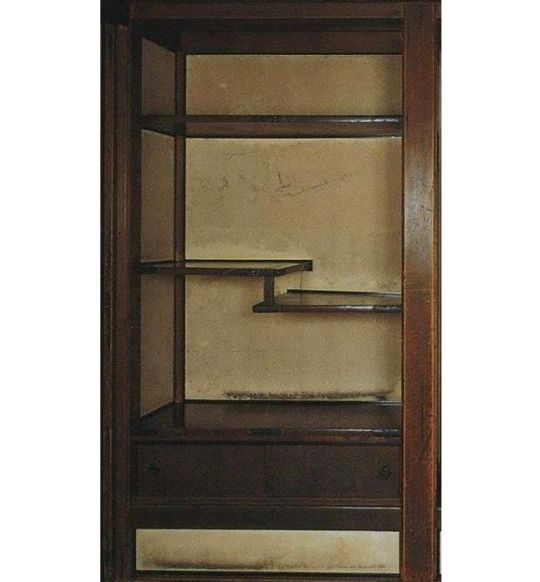

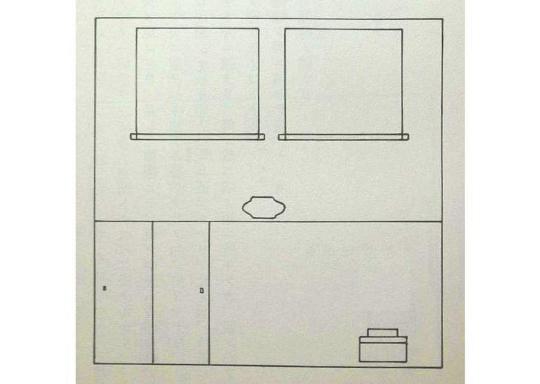

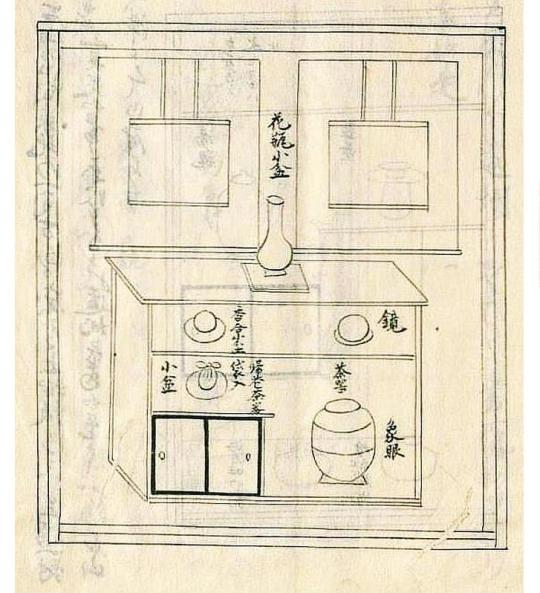

Nampō Roku, Book 4 (24.2): Four Arrangements for the Dashi-fuzukue [出文机] (Tsuke-shoin [付書院]), Part 2; and Rikyū’s Brief Closing Remarks.

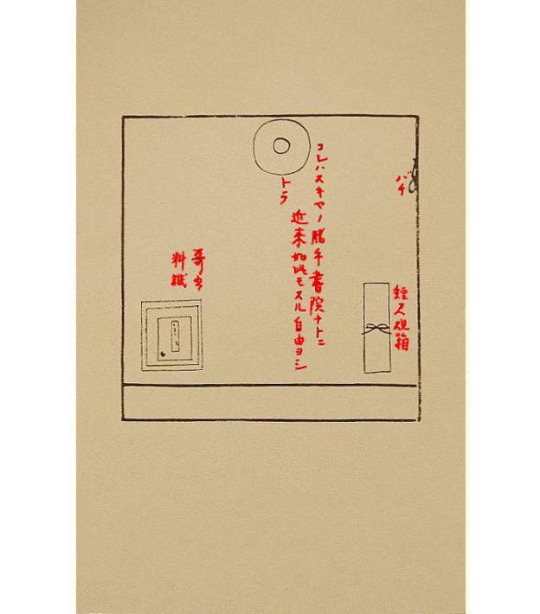

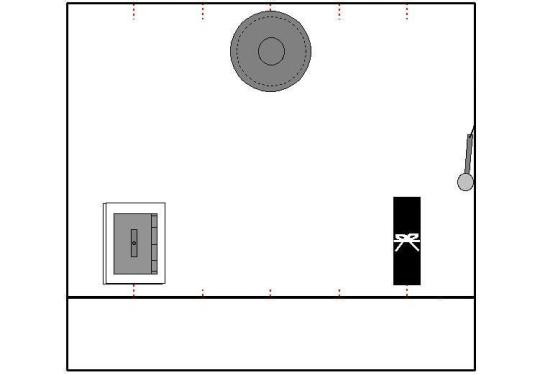

[The writing reads (from right to left): bachi (バチ)¹; tanzaku・suzuri-bako (短尺・硯箱)²; kore ha sukiya no katte-shoin nado ni, chika-goro konna mo suru, ji-yū yoshi (コレハスキヤノ勝手書院ナトニ、近來���此モスル、自由ヨシ)³; dora (トラ)⁴; kasho・ryōshi (哥書・料紙)⁵.]

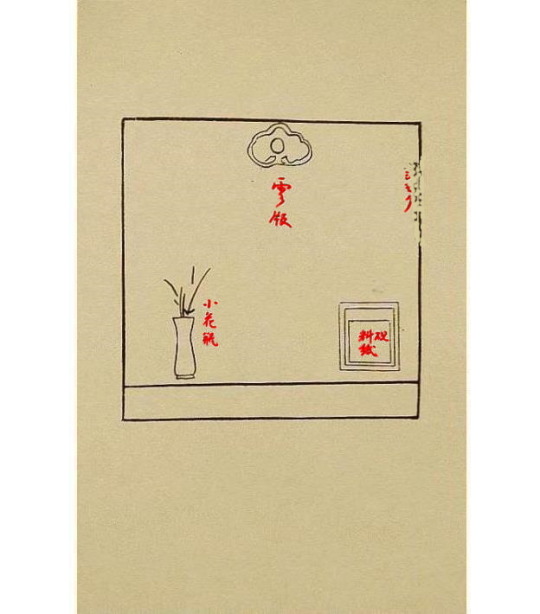

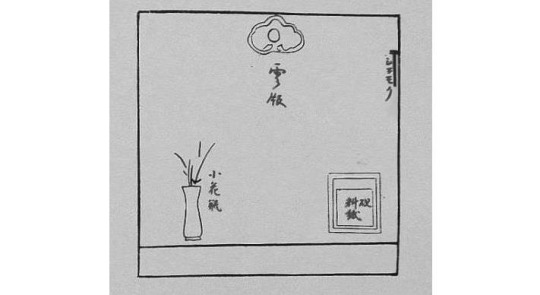

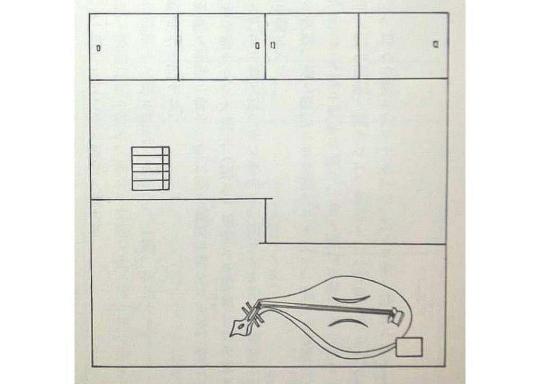

[The writing reads (from the right): shimoku (シモク)⁶; suzuri・ryōshi (硯・料紙)⁷; un-pan (雲版)⁸; ko-kabin (小花瓶)⁹.]

_________________________

¹Bachi (バチ).

This is the striker for a gong. It consists of a relatively short wooden haft, to which a round, ball-like head (usually made of leather secured at the neck over a ball of twine, for the necessary resilience).

As with the kanshō [喚鐘] (which was mentioned in the previous post), the gong was struck with the bachi while the host sat on the floor in front of the dashi-fuzukue.

²Tanzaku・suzuri-bako [短尺・硯箱].

A tanzaku・suzuri-bako [短冊硯箱] is a rather elongated* sort of suzuri-bako, with a lower compartment in which tanzaku [短冊] (poetry cards) could be stored.

The box for the tanzaku is shown on the left, and the lid is on the right. Above the rather elongated suzuri is a silver mizu-ire [水入]. The lid is usually tied on with a pair of cords that are attached to small kan [鐶] near the bottom of the box (the cords are not shown in this photo). ___________ *Tanzaku are usually 1-shaku 2-sun long, and 2-sun wide, and the box would have had to be perhaps 1-sun larger than this in order to allow the tanzaku to be removed easily.

³Kore ha sukiya no katte-shoin nado ni, chika-goro kon-na mo suru, ji-yū yoshi [コレハスキヤノ勝手書院ナトニ、近來如此モスル���自由ヨシ].

Kore ha sukiya no katte-shoin nado ni [コレハスキヤノ勝手書院ナトニ]: a katte-shoin is a construction more commonly seen in the early sukiya [数奇屋] (a wabi-style tearoom -- in this case, a 4.5-mat room with a 6-shaku toko, with a dashi-fuzukue on one side of it*).

Chika-goro konna mo suru [近來如此モスル]: chika-goro [近來]† means “at this time,” “in the present,” “recently;” konna mo suru [如此も爲る] means “it is still done like this.”

Ji-yū yoshi [自由ヨシ]: ji-yū [自由] means “to do as one likes”: thus, “it is appropriate to do as one feels best.”

The dora [銅鑼]‡ was more commonly used in the wabi-sukiya, rather than in the more formal shoin (where the gakki [樂器] were usually percussion instruments originally used in the temple setting). ___________ *We must remember that the Shū-un-an documents with which these sketches were associated dated from the beginning of Jōō’s public career. The small room did not appear until 1554; prior to that time, the sukiya was always a 4.5-mat room, with a 6-shaku toko.

†It is also important to keep in mind that these kaki-ire [書入] were added to the sketches sometime after Jitsuzan presented his copy of the Nampō Roku to the Enkaku-ji. Thus “chika-goro” refers to sometime during the eighteenth century (or after -- it is not clear precisely when these notes were added, though some speculate it was during Jitsuzan’s lifetime, when the secret discussions on the way to interpret these drawings were beginning).

‡The dora [銅鑼] was first used by ships as a sort of fog-horn -- to announce their presence (and intended entry into port) during foggy weather. They were, thus, much more “humble” than the percussion instruments that were created to be played in the temple, to accompany the chanting of prayers.

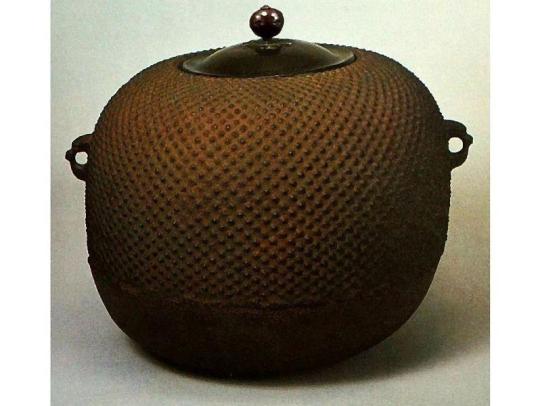

⁴Dora [トラ].

The dora [銅鑼] is a gong. The sketch shows a Chinese nipple-gong. The face of Korean gongs was usually flat (though sometimes incised with concentric circles to indicate the center). The sound of the two are similar -- though more care has to be taken to hit the Korean gong in the center, since otherwise the sound will be discordant†.

It is said that the Chinese gongs were originally made for ships to announce their approach to the harbor -- since the deep sound carries well in fog*.

The similarity of the sound of a dora to a temple bell heard at a distance was noted very early (probably already on the continent, among the townsmen followers of wabi‡, long before chanoyu was brought to Japan), so that the way to play the gong was intended to imitate the sound of a temple bell (and its echo). ___________ *Many of the antique dora that appeared in Japan during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are said to have been brought from the Philippines, where the natives were apparently using them as war-shields. However, the aborigines are not known to have possessed bronze-making abilities at that time; and these gongs seem to have come into their possession as a result of the wrecks of Chinese shipping in their territories.

Japanese-based merchants from Sakai and Hakata began to visit the Philippines during the fifteenth and sixteenth century, to trade with the Europeans, in addition to their port calls in other East and Southeast Asian countries.

†Korean gongs seem to have originated as instruments intended to scare away malicious influences during purification rituals. Thus their ability to produce audibly disturbing sounds was considered a benefit.

‡These people seemed to admire the spiritual aspect of things like chanoyu, though they were not monks. Playing the gong so that it resembled a temple bell was, therefore, a sort of fiction. This is an attitude that deeply influenced the development of wabi tea.

⁵Ka-sho・ryōshi [哥書・料紙].

A ka-sho [歌書]* is a book of poems.

Ryōshi [料紙] is writing paper. Possibly just one or two pieces, folded in half, to keep the book from coming into direct contact with the surface of the desk (which might have dust or ink residue present that could damage the book). ___________ *Ka-sho [哥書] is a rather inelegant abbreviation, though this form is commonly found in machi-shū writings. It is difficult to believe that it was ever used in Jōō’s authentic writings.

—————————————————-—————————————————

Shibayama Fugen begins by noting that the present arrangement of the dashi-fuzukue would be appropriate for an uta-kai [歌會], or a renga-kai [連歌會], or a gathering of that sort*.

The dora is suspended from a hook attached to the middle of the ceiling above the dashi-fuzukue. The bachi [撥] is suspended on the side of the writing desk closest to the katte (in other words, the opposite side from where the tokonoma is located).

A tanzaku・suzuri-bako [短冊硯箱] is shown on the right, and ka-sho [歌書]† (a book of poetry) is shown, resting on a piece of ryōshi, on the left. The object resting on top of the book is a bun-chin [文鎮]‡. ___________ *Kono kazari ha uta-kai, renga-kai nado no kazari naru-beshi [此ノ飾ハ歌会、連歌会ナドノ飾ナルベシ].

An uta-kai [歌会] is a poetry competition, where two teams compete with each other, proposing verses according to a specific series of topics; a renga-kai [連歌会] is a linked-verse competition, where the contestants utilize part of the preceding participant’s verse to create a new one, with the purpose being to create a single, long poem of a certain number of links.

†A ka-sho [歌書] is a book of poems.

‡A bun-chin [文鎮] is a paperweight. While a generic sort of bun-chin (a long bar of polished brass, with a small knob by means of which it can be handled) is shown in the sketch, more fanciful shapes were also common -- and likely would have been used, if available, and if the shape were appropriate to the occasion.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

⁶Shimoku [シモク].

Shimoku [シモク] appears to be a miscopying of the word shumoku [シュモク = 撞木], probably because the original manuscript was already in a poor state of preservation when Jitsuzan took his copy. The sketch may be reconstructed as follows.

The shumoku is a mallet-shaped striker, used to sound the un-pan [雲版] while the host remains seated in front of the dashi-fuzukue.

The shumoku used for an un-pan has a shorter handle, and a broader head than the one used to sound the kanshō. This kind of shumoku is sometimes suspended (upside-down) from a loop of cord inserted through the hole in the handle (and some of the versions of this sketch show that orientation).

⁷Suzuri・ryōshi [硯・料紙].

A suzuri [硯] (ink stone), displayed on top of a packet of ryōshi [料紙] (writing paper) that has been folded in half.

⁸Un-pan [雲版].

An un-pan [雲版] is a rather flat, bronze percussion instrument, which produces a sound somewhere between a gong and a pair of cymbals (depending on the size and shape). As the name suggests, it is more or less cloud-shaped.

The un-pan is not usually flat, but generally has a recurved rim (the deeper the rim, the more gong-like the sound). This was another of the traditional Buddhist instruments installed in the bell-hall along with the large bell, drum, and wooden gong. (These instruments were usually played by the monks at dawn and dusk, as the sun rose above, or slipped below, the horizon.)

Like the kanshō, it, too, was played by striking with a wooden mallet.

⁹Ko-kabin [小花瓶].

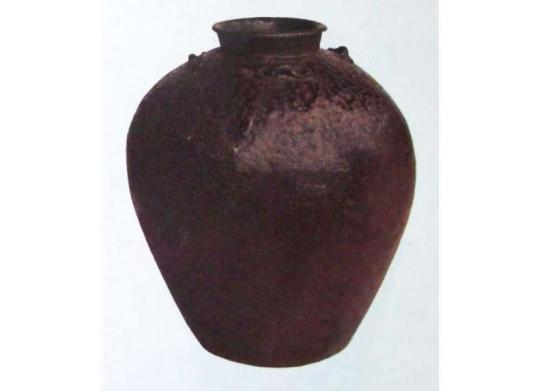

A small flower-vase, such as Rikyū’s treasured Tsuru-no-hito-koe [鶴ノ一聲]*, shown below.

The word ko-kabin specifically refers to a vase that was much too small to hold a formal rikka [立華] style arrangement.

Only a single flower (or a small twig)† could be placed in this kind of hanaire -- and, indeed, the flowers as arranged in a ko-kabin were the precedent for the “cha-bana” [茶花]‡. ___________ *Early sources give the original name as Tsuru-no-hashi [鶴ノ波子] (which describes the pattern of waves around the foot of the hanaire). Rikyū changed its name to memorialize an episode that seems to have occurred in the 1570s.

†Rather than being considered to be a “flower arrangement,” this kind of thing was usually done as a way to appreciate the flower in question. For example, a small branch of plum blossoms would be placed in this kind of vase so that the color and fragrance could be enjoyed close at hand.

‡In Chinese, cháhuā [茶花] refers to the late autumn- and winter-flowering forms of the camellia, as well as those cultivars of the tea plant that are grown for their attractive flowers. The former are all hybrids between the true camellia (Camellia japonica), which flowers in the spring, and the tea plant (Camellia sinensis) -- which can flower at any time of the year, but predominantly in the early autumn. Some of these are ancient, natural hybrids (and so appear to us to be purely camellias, rather than hybrids), while others are what the Japanese refer to as sazanka [山茶花] (Camellia sasanqua). According to the Japanese horticultural definition, tsubaki [椿] (the “true” camellias) are distinguished from the sazanka by the fact that sazanka loose their petals one by one, while tsubaki drop the entire corolla as a unit. While this is valid in first generation hybrids, complex natural hybrids often behave more like camellias than their tea parent.

Be that as it may, classical references dating to the Ming dynasty times (and possibly earlier), speak of Chinese connoisseurs of tea drinking who would display a twig of the tea plant, when in bloom, in such small vases on their desks or tea tables, and it was apparently from this practice that the tradition of cha-bana developed.

——————————————————————————————————

Shibayama Fugen explains that the kane employed in this sketch are exactly the same as in the previous example.

The un-pan is suspended from the ceiling on the central kane; and the suzuri and flower-vase stand on the right-most and left-most kane, respectively.

==============================================

[Rikyū’s concluding remarks¹:]

Migi ichi-ran mōshi-sōrō shoin-kazari ika-hodo mo shina ōku sōrae-domo, korera no wakare ni te ichi-dan koto ka mōsu majiku sōrō [右一覧申候書院飾いか程も品多く候得共、此等之分にて一段事欠申間敷候]².

Kashiku [かしく]³.

Sōeki han [宗易判]⁴.

Nambō [南��]⁵.

_________________________

¹This title is not present in the original. These remarks simply follow the last sketch.

²“Having read through the foregoing, [I am amazed at] the great number of arrangements for the shoin [that you have collected together]. But for all your understanding of these things, there is still so much more that you do not [yet understand].”

³Kashiku [かしく] is a traditional, standard -- albeit somewhat effete -- closing for letters and things of that sort. It is usually translated* “sincerely yours,” or “respectfully yours.”

Shibayama Fugen’s teihon [底本] has kashiko [かしこ], but this is simply another form of the same greeting. ___________ *The actual meaning would depend on the kanji with which the expression is written -- ranging from auspicious wishes, to fear (of having given offense). Traditionally this term seems to have been used by women -- and affected by the excessively effete chajin of the old capital during the Edo period.

Rikyū’s authentic writings are never signed in this way.

⁴Sōeki han [宗易判] means Sōeki’s name-seal. Perhaps his stylized signature (kaō [花押]) was written here.

⁵Nambō [南坊], Nambō Sōkei [南坊宗啓; ? ~ 1594], the purported recipient of these comments.

The closing suggests that Sōkei presented a collection of documents to Rikyū for his review, and his comment was that while the collection is exhaustive, there is still much that Sōkei does not know. This is the way that the first six books of the Nampō Roku end.

These concluding remarks are assumed to have been fabricated by Tachibana Jitsuzan, though it is entirely possible that one of the other parties who had accessed the Shū-un-an documents between 1595 and 1680 (agents of the Edo bakufu, and representatives of the Sen family) might have added these remarks -- to disguise the actual origins of this material. This was because it was at this time that efforts were being made to discredit both Jōō and Furuta Sōshitsu, in favor of Rikyū (since, in the absence of access to Rikyū’s actual teachings -- the result of the damnatio memoriae imposed by Hideyoshi, and furthered by the efforts of the machi-shū under Imai Sōkyu, who attempted to restore chanoyu to its state during Jōō’s middle period -- his importance and influence had to be demonstrated somewhere, and this was most easily accomplished by stating that many of the practices that were known to have started in the sixteenth century, actually originated with him). Thus, most of what we commonly understand to be the achievements of Rikyū today, were actually things begun by Jōō and Oribe (even when those practices were could also be confirmed as having been indulged in by Rikyū himself).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Record of Kaikeidou Servants (excerpts 11 through 15)

Excerpt from the Sea God Bookstore's "Record of Kaikeidou Servants:" a text whose author and editor are both unknown.

Negoro: CHEEERS! Sarasa: Cheeers!

Negoro: Man, I'm totally beat. I mean, geeze, I had to fight through a volley of danmaku every time just to ask them a few questions.

Sarasa: Wha~a? Are you telling me you didn't get permission from them?

Negoro: C'mon, that'd be such a pain in the butt. Talking back and forth, writing all those formal letters... it's way better to just get up in their face like "tell me about such-and-such if I win this fight," isn't it?

Sarasa: Is THAT why everyone was making those suspicious faces? C'mo~on, the Sea God Bookstore is gonna get su~uch bad reviews for this...

Negoro: Eh, not my problem.

Sarasa: Miss Kaidou's gonna get so~o mad at us again...

Negoro: What are you talking about? We're Kaidous too, aren't we?

Sarasa: Bringing out the old wordplay again, I se~ee.

Negoro: Hey, speaking of which-- let's do that thing again! It's been forever!

Sarasa: Huh? Who would we even be addressing, tho~ough?

***

Negoro: The people's gossip lasts for 75 days-- and stretches to 75 fathoms below!

Sarasa: We hold all the wonders of those depths in our very hands!

Negoro: We are scholars who pursue both the written and divine word!

Sarasa: A publishing company that births a vast sea of printed type!

Both: Together, we are...! The Sea God Bookstore's Kaidou branch!!

***

Negoro: We said it! We said our signature lines, Sarasa!

The Sea God Bookstore's Berliner Lady Negoro Kaidou (海堂 ねごろ)

Sarasa: C'mo~on, quit hugging me so tightly! You're making it hard to breathe!

The Sea God Bookstore's Blanket Girl Sarasa Kaidou (海堂 さらさ)

Negoro: Y'know, though. That last one we interviewed, uh... Miss Owari, right? The other sisters clammed right up when it came to her.

Sarasa: Oh, abo~out that. Miss Hananishiki, the next youngest, told me why. They were worried that their Eldest Sister would, like, punish them or something if they said too much, so they were all trying to avoid making any inconvenient comments~.

Negoro: Ah, that explains why they were all so cagey. I guess she's kind of intimidating, being the oldest and all, huh?

Sarasa: Both of us are ba~asically only children, so I guess we wouldn't really know. When you think about it, having nine whole sisters would be pretty amazing even for humans, right? Let alone mermaids.

Negoro: Oh, speaking of humans. I just remembered that some time ago, the Kaikeidou tried to invite some humans in so that they could make a bigger name for themselves. According to Lady Mikoto and Megumi and the like.

Sarasa: They said that our ocean isn't a place people visit very often, so at the rate things were go~oing, the whole ocean itself would disappear from Gensokyo.

Negoro: Wait, doesn't that mean we were in some pretty big trouble, too?!

Sarasa: Miss Kaidou didn't seem very panicked about it, though. When she was giving me the manuscript for the article, I asked her abo~out it, but she just said "nah, does that really matter?".

Negoro: Uh, Miss Kaidou's definitely not that laid-back?!

Sarasa: Whenever I go to talk to her about work, she's aa~allways casual.

Negoro: Whenever I send in my reports, she sends them back totally covered in red pen...

Sarasa: Anywa~ay, getting back on topi~ic...

Negoro: Sarasa, you can be real cold sometimes.

Sarasa: Miss Hananishiki was the one who said that all the sisters' abilities were the same, except for Miss Owari's.

Negoro: Oh, yeah. In the first place, Miss Owari was born as Lady Mikoto's immediate daughter, and all the other sisters were-- at least on paper-- born from Miss Owari. When you think about it, that would normally make Miss Owari the other nine sisters' mother...

Sarasa: But both Miss Owari and the other nine sisters were born from foam by Lady Miko~oto, so all ten of them are effectively siblings.

Negoro: Apparently, the sisters from Hananishiki on down were originally meant to be created as 'second attempts' if Owari failed, so they would've been born with divine powers like hers too. But since Owari learned how to wield her divine nature right off the bat, they just made her a bunch of regular sisters with no divinity instead.

Sarasa: Miss Kasumi the clam youkai knew a lo~ot about that part. She was the very first guardian of the Kaikeidou's front door, after all.

Negoro: And so, the nine other sisters aren't equipped with any special powers. They've got the same capabilities as average mermaids like us.

Sarasa: If I had to think of any bi~ig difference, I guess Miss Hananishiki is re~eally good at cooking? This one time, she let me have ju~ust a few of these green sturgeon eggs she whipped up.

Negoro: BWH-- Oh my god, why didn't I hear about that...?! WHY DIDN'T SHE INVITE ME TOOOOO?!

Negoro: Hey, now that I think about it... if the goddess of the entire sea came to Gensokyo, is the outside world, like, doing okay?

Sarasa: Oh, yeah, they're doing fi~ine. I heard a~all about it from Lady Mikoto.

Negoro: Huh? When, exactly?!

Sarasa: Lady Mikoto sa~aid that she's just one descendant of the sea gods from ancient lege~ends, and there's plenty of others besides her, so it's still okay out the~ere.

Negoro: Huh!

Sarasa: Y'see, Lady Mikoto used to be a sea goddess who lived in a bi~ig lake, with that special power of hers that can create life. But with just lakewater, she couldn't support all the creatures she'd created.

Negoro: 'Cause it was fresh water, yeah.

Sarasa: And as she was worrying about that, this one gi~irl-- the one named Lady Otohime, who were interviewing toda~ay-- she helped Lady Mikoto turn the lakewater into a fountain of life that could support a~all the sea creatures.

Negoro: And that's how this little "ocean" that we live in was born.

Sarasa: Ye~ep. But then, since they made the lake wa~ay too big in the process, Gensokyo was about to like, burst at the seams...! So that one lady-- the Hakurei shrine maiden, I think? She came down here and told them to stop.

Negoro: Aaaah! I remember that part! I was THERE for it!

Sarasa: Huh? Did something happe~en?

Negoro: Not just SOMETHING! That Hakurei maiden or whatever slapped me right outta the water on her way down!

Sarasa: ...Oh~h, yeah, you did have that big bump on your head that one ti~ime.

Negoro: See, all of a sudden it sounded like there was this big commotion up on the surface, right? And I was like "ooh what's happening...?" and I went on up to look, right? When suddenly, BAM! Some what's-her-face cannonballs down in here, and as soon as she sees me, she starts hurling amulets and whacking me with a giant ritual rod! ...And then, later, someone else started throwing weird stars that tasted like candy, a-and, and shooting huge lasers and stuff... *snf* a-and... *sniff* and on t-top of everything else... there, there were! There were these, like, nuclear kaboom things, a-and... *gross sobbing*

Sarasa: Oh~h, there, there. You did your best out there, Negoro. I know it must have been re~eally scary...

Negoro: *snrf.* .....And then, like, a little after that is when the ocean shrank back down and stuff. Was that 'cause of-- what did you call her? The Hack-and-Slash shrine maiden?

Sarasa: Hakurei shrine maiden.

Negoro: Yeah, her. ...Okay, wow, we're getting off-topic. So, basically, the reason we, Miss Kaidou and the Bookstore, and the Kaikeidou itself are all here, is because of Lady Mikoto and that Lady Otohime you mentioned?

Sarasa: Yep, that's basically it. When we head over there next time to give them a finished copy of the book, maybe we should give them something to show our thanks?

Negoro: Hm. What kind of present can we even give them...? Like, they're gods, but we're just youkai, y'know?

Sarasa: How about we bring them some of our scales?

Negoro: Uh. That seems kind of... blood sacrificey.

Negoro: Although, the Kaikeidou and its sea being created are what led to us and the Sea God Bookstore existing, so I guess just writing this book is a thank-you in its own way?

Sarasa: Yeah, you could put it like that.

Negoro: We can't dance or fight like the Kai sisters, either. I'm so jealous of all those cool games they get to play...

Sarasa: Negoro, you want to fight?

Negoro: Well, I wanna play-fight.

Sarasa: Why not play-fight with Miss Kaidou, the~en?

Negoro: You really think she'd deign to play with us? Plus, there's her ability to worry about too... even if we had a proper match, it'd probably end with her reading every single one of my moves.

Sarasa: Then... how about me?

Negoro: You're way too slow. It wouldn't even be a competition.

Sarasa: Aww...

Negoro: Hey, now that I think about it. When I went to do interviews at the Kaikeidou this one other time, there was this kind of weirdly dramatic atmosphere, right? And everyone was in such a hurry that I couldn't get any info out of them at all. I think they said there was an intruder there...

Sarasa: Really~?

Negoro: I never met whoever it was, but apparently some super-strong youkai broke in, and Minamo and Suzuri were all sprawled out on the ground...

Sarasa: Sounds really dangerous.

Negoro: Well, I got as far as the entry hall and then high-tailed it outta there. What do you think it was, though?

Sarasa: I wo~onder... Maybe it was, like, a really big-name youkai~? Y'know, like the ones we've heard rumours about lately.

Negoro: A really big one... well, you've got your nurarihyons, your orochis... oh, not to mention the kuda--

Sarasa: Hey, Miss Kaidou's back!

Negoro: Miss Kaidou...!

Production:

Sea God Bookstore: "Kaidou" ・A bookstore that produces books detailing key events in the deep seas of fantasy. Deep, deep down, at depths that humans can't hope to reach, they keep a quiet collection of books found nowhere else; records of mysteries more distant than the stars. The only ones who know whether these events are fantasy or reality are the various "studios" lined up within the Bookstore's walls.

・"Kaidou" is one of the studios within the Sea God Bookstore, run by one of the Bookstore's managers, Minogiku Kaidou. Its employees all receive the surname "Kaidou," based on Minogiku's studio name. The other studios mainly do archival work, but "Kaidou" is one of the few that publish books and magazines. They serialize magazines, journals and tabloids, compile, edit and publish full-fledged books, and so on.

Authors:

Sarasa Kaidou (海堂 さらさ) ・A journalist employed at "Kaidou" in the Sea God Bookstore. She is Minogiku Kaidou's direct subordinate, and in this book, she conducted the interviews for the six elder Kai sisters. One of the mermaids native to the ocean surrounding the Kaikeidou; after coming into existence in Gensokyo due to certain particular circumstances, she was adopted by Minogiku Kaidou. It seems she has some past connection to the outside world...?

Negoro Kaidou (海堂 ねごろ) ・A journalist employed at "Kaidou" in the Sea God Bookstore. She came to work at the Bookstore with Sarasa's help, and is currently employed as one of Minogiku Kaidou's subordinates. She conducted the interviews for the four youngest Kai sisters. Hails from the ocean surrounding the Kaikeidou; were it not for her job at the Bookstore, she would be like any other mermaid who swims carefree in the sea.

etc...

Editor:

Minogiku Kaidou (海堂 水乃菊) ・The administrator of the Sea God Bookstore's "Kaidou" studio; within the studio itself, she serves as the chief editor. She's a mermaid with a keen sense for information, which she makes full use of to produce the various serial publications she oversees. On top of her deep craving for information, she makes a strong habit of guessing what people are thinking, so she's often mistaken for a satori; however, she's 100% mermaid. As can be inferred from how she gives the Kaidou studio name to all her direct subordinates, she's deeply possessive in addition to knowledge-hungry. If you're foolish enough to spark her interest in you, she may very well steal all the information you have. Prepare thyself.

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (11c): the Kaki-ire [書入], Part 2: the Uma no Hi-ai [午ノ火相] and the Tori no Hi-ai [酉ノ火相].

(Continuing the kaki-ire [書入].)

○ When we speak about the Uma no hi-ai [午の火相], this is the hi-ai for a gathering [that will be] held in the afternoon¹.

Around noon, the interior of the ro [containing the remains of the fire] from the morning should be refreshed, and a full set of charcoal should be laid². This [fire] will develop into the shita-bi [下火], that will [be used] when the guests enter [for a gathering in mid-afternoon]³. 〚[It is necessary to rebuild the fire at this time because] the strength of the dawn fire will be fading away⁴.〛

○ As for the Tori no hi-ai [酉ノ火相], this is the hi-ai for the night gathering⁵.

○ This [Tori no hi-ai] has the same feeling as [the hi-ai established] at dawn⁶. 〚From the time when the light starts to fade from the sky, guests might arrive [early],〛so [the host] should understand that the way things are done mirrors [what was done] at dawn [if guests arrive early at that time]⁷.

○ Around the [Hour of the] Rooster, the hi-ai should be refreshed.

After the interior of the ro has been cleaned, [it is possible for guests] to enter the room [early]. [In this case,] things are done in a manner similar to an ordinary night gathering⁸. If they came before [the host] had cleaned [the ro], they should sit [in the koshi-kake] chatting leisurely. This kind of guest should not ask to be allowed to watch [the host's actions] until after the shita-bi [has been arranged in the ro]⁹.

○ If the host is a master, [the guests] should certainly [consider] doing something like that -- and it is the same at dawn¹⁰.

○ Whether at dawn, or at dusk, because there will be nothing to entertain [the guests] while they wait [for the kama filled with cold water to come to a boil, so tea can be served], there is the case where an incense burner, or something of the sort, is brought out [so that the guests can pass the time appreciating incense]. This is the usual way things are done [on occasions of this sort]¹¹.

In a 4.5-mat room, there is [also] the case where a [box of] tanzaku [短尺], a suzuri [硯], and other such things, are placed out [on the tsuke-shoin, or in the toko], so that -- according to [the inclinations of] the guests -- they may [enjoy writing or reading] poetry¹².

But [when the guests are invited to entertain themselves like this] it is very important for the host to control the length of time that is passed in this way¹³.

_________________________

◎ In this section, the discussion moves on to the Uma no hi-ai [午ノ火相] and the Tori no hi-ai [酉ノ火相] -- the hi-ai at noon and at dusk respectively.

It is extremely important to clarify something, since nothing is really said about this in the text*, and the idea is the complete opposite of what we usually imagine chanoyu to be today, based upon the teachings and practices of the modern schools.

What we would consider to be a “full” sumi-temae, where a complete set of charcoal is arranged in the ro around a shita-bi (a process similar, in most of its technical details, to what is usually called the sho-zumi temae [初炭手前] today, the arrangement of the charcoal at the beginning of the shoza) is what the host was supposed to do at dawn (to establish the Tora no hi-ai), at noon (when he repairs the fire to establish the Uma no hi-ai), and at dusk (to establish the Tori no hi-ai). Almost always, these processes were never witnessed by the guests†; and the attention to the fire at dawn, noon, and dusk, was supposed to be undertaken every single day, regardless of the time of the chakai -- or, indeed, irrespective of whether a chakai was going to be held on that day or not.

In contrast to this, the sumi-temae at the beginning of a chakai -- whether in the morning (for an asa-kai [朝會]), in the afternoon (for a hiru-kai [晝會]), or at night (for a yo-kai [夜會]) -- most closely resembled the modern schools’ go-sumi-temae [後炭手前] -- the sumi-temae that is inserted between the service of koicha and usucha (when these are prepared in separate temae) -- which entails repairing the fire by adding no more charcoal than the host deems necessary to keep the kama boiling until the service of the gathering has been concluded. This is how far modern-day chanoyu has diverged from the chanoyu of Rikyū and Jōō, and it is the reason why the old writings are nearly impossible for modern people to understand. ___________ *Because its intended audience were aware that the most common times for chanoyu were mid-morning and in the early evening (and only rarely in mid-afternoon) -- this is why the old writings always focus their attention on the asa-kai [朝會] (which usually was scheduled to begin either in the middle of the Tatsu-no-koku [辰の刻], around 8:00 AM, or at the beginning of the Mi-no-koku [巳の刻], around 9:00 AM) and the yo-kai [夜會] (which typically started either during the second half of the Tori-no-koku [酉の刻], or at the beginning of the Inu-no-koku [戌の刻], in other words, at 6:00 or 7:00 PM), while things like the (modern-preferred) shōgo chaji [正午茶事] (which requires the guests to gather at the site of the chakai around 11:30 AM) are never mentioned at all.

†Because these occasions were regarded as “maintenance work,” it was inappropriate for guests to be invited to come at such times -- so the documented instances where a guest was present were usually the result of a guest arriving spontaneously (this is the way most scholars interpret the “Tennōji-ya Sōkyū and the snowy dawn” episode -- though that is actually not correct), or of one coming early for a gathering that was scheduled for later in the day.

¹Uma no hi-ai to iu ha, hiru no kai no hi-ai nari [午ノ火相ト云ハ、ヒルノ會ノ火相也].

Uma no hi-ai [午の火相] is the hi-ai that is established at noon.

In other words, the fire that is repaired* at noon is what will be used at a gathering held in the afternoon†.

Hiru no kai [晝の會] refers to a chakai hosted sometime between noon and dusk‡. Here it refers to a gathering that saw the guests arrive at the middle of the Hitsuji-no-koku [未の刻]** (2:00 PM), or the beginning of the Saru-no-koku [申の刻] (3:00 PM). ___________ *At dawn and at dusk the ro is emptied, and a full set of charcoal is laid around embers. These fires are based on a dō-sumi [胴炭], a long piece of charcoal (it measures 5-sun long, and is usually between 1-sun 8-bu and 2-sun 1-bu in diameter) which is laid on its side on the side of the ro that faces toward the guests’ seats.

At noon, however, the remnants of the dawn fire are collected together in the middle of the ro, and the charcoal arranged around this. At noon, the foundation for the fire is a wa-dō [輪胴], a cylindrical piece of charcoal (it measures 2-sun long, and is usually a little over 2-sun in diameter) that is stood upright on the side of the ro toward the guests.

The reason why the largest piece of charcoal should be placed on the side of the ro that is facing toward the guests is because it both moderates the heat that radiates in that direction (this is most important when one of the guests is seated near the ro, such as when it is a mukō-ro), and also tends to prevent an eruption of sparks from shooting out of the ro toward them (which could be disconcerting, if not usually dangerous).

†According to Rikyū’s own kai-ki [會記], such gatherings usually started at the beginning of the Saru-no-koku [申の刻] (3:00 PM).

‡The use of hiru [晝] to mean noon is relatively recent. Classically, it referred to the daytime hours, the hours when the sun is in the sky. And, together with asa [朝], it defined the daylight hours -- asa being used for the part of the day from dawn to noon, and hiru being used to designate the time between noon and dusk.

**I have seen Hitsuji-no-koku [未の刻] written Hitsuji-no-koku [羊の刻], using the kanji for sheep (hitsuji [羊]), since this is the “Hour of the Sheep;” however, this rendering is certainly non-standard (and many would argue that it is wrong).

²Asa yori no ro-chū Uma-no-toki no koro ni aratame, ittan suru [朝ヨリノ爐中午ノ時ノ頃ニアラタメ、一炭スル].

Ro-chū [爐中] means inside the ro; the interior of the ro.

In other words, around noon the interior of the ro should be cleaned up. The white coating of ash should be scraped off (using the hibashi), the dō-zumi [胴炭] (which will be almost burned through at this point in time) should be broken in half (again, using the hibashi), with the halves being stood upright, and then all of the burning pieces of charcoal should be collected together in the middle of the ro. Then shimeshi-bai is sprinkled around the perimeter of the fire, where the new charcoal will be stood.

Ittan suru [一炭する]: the layer of gitcho that were piled on top (in the fukube) are moved into the hai-ki until the wa-dō [輪胴] (see the first sub-note under the previous footnote -- the wa-dō is placed on the bottom of the fukube, along with one more dō-sumi, and then they are covered over with gitchō) is exposed. Then the wa-dō is moved into the ro and stood on the side of the fire toward the guests’ seats. Then gitchō (selected from those in the hai-ki) are arranged in a semi-circle around the burning embers.

The gitchō should be leaning inward slightly, since this helps them to catch fire more easily.

³Kore sunawachi kyaku-iri no shita-bi ni naru nari [コレ則客入ノ下火ニナル也].

Kore sunawachi [これ則ち] means this will be (what serves as the shita-bi after the guests enter the room).

Kyaku-iri [客入] means the arrival (or entry) of the guests. However, it is extremely important to understand that the arrival of the guests is not imminent at the time when this set of charcoal is being laid*. The hi-ai established at noon will be used as the shita-bi for a gathering that begins in mid-afternoon (around 3:00 PM). ___________ *Even some scholars (most of whom have close ties to one of the modern schools) seem to be confused over this point -- a result of the overwhelming prevalence of the shōgo-chaji in the modern tea world.

⁴Following the preceding sentence, Shibayama Fugen’s teihon [底本] adds the words akatsuki no hi-kagen to ha tou nari [曉ノ火加減トハ遠フナリ], which means “the strength of the dawn fire is fading away*.” ___________ *Tou [遠ふ = 遠う] is a rarely seen archaism.

Cf. the first example cited here: https://furigana.info/w/%E9%81%A0:%E3%81%A8

Here, tou [遠う] means something like “receding into the past,” “fading into the past;” “becoming more distant all the time.”

⁵Tori no hi-ai to ha yo-kai no hi-ai no koto nari [酉ノ火相トハ夜會ノ火相ノコト也].

Tori no hi-ai [酉の火相] refers to the hi-ai established at dusk. As in the previous instances, the guests are usually not present when this is done.

The procedure is similar to what is done at dawn, albeit the ro has to be cleaned out first.

The host begins by bringing a handa-hōroku [半田炮烙] and soko-tori [底取] (and, today, a pair of naga-hibashi [長火箸]*, though in Rikyū’s day it seems that the ordinary ro-hibashi -- with wooden handles to protect from the heat -- were used) out to the utensil mat. After removing the kama to the mizuya, all of the remaining pieces of charcoal and larger embers are moved into the handa-hōroku. Then the soko-tori is used to scoop up the surface layer of ash and minute embers within the circle defined by the legs of the gotoku, and this is also poured into the handa-hōroku. Then, using the hibashi and soko-tori, the ash surface is smoothed into a slightly depressed bowl shape, and then shimeshi-bai is sprinkled over the entire surface of the ash in the ro.

Several of the larger pieces of burning charcoal are returned to the ro, where they are grouped together in the center, to form the shita-bi. Then a full set of charcoal is arranged around the burning pieces, as usual†. Then the handa-hōroku, containing the remaining pieces of burning charcoal and hot ashes that were removed from the ro, is carried out to the mizuya.

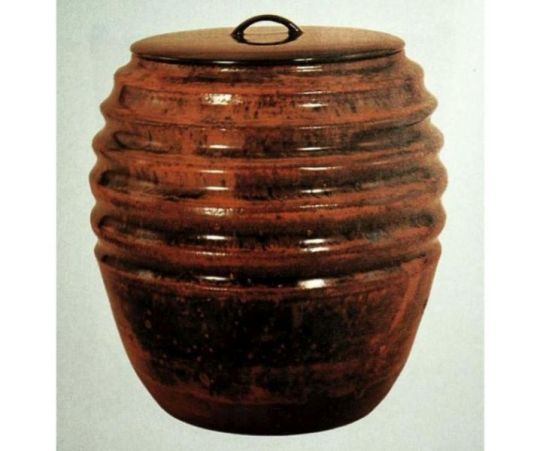

The host then cleans the kama by dipping hot water out with a hishaku and pouring this over the sides until it is half empty. Then, protecting the sides of the kama with a pair of folded towels (the oil of the hands can damage the patina of the iron), the kama is picked up and all of the remaining water poured into the chakin-darai. After rinsing the bottom of the kama by pouring hot water over it with a hishaku, it is scoured with a sort of brush called a kiri-wara [切り藁]‡. After rinsing, the kama is turned over again, and filled (to a point just below the bottom of the kan-tsuki) using the dawn water that was stored in the mizu-kame [水甕]**. Then the kama is carried out into the tearoom, and placed in the ro. And after sweeping the utensil mat, the host turns his attention to other tasks that he must undertake before darkness falls.

Tori no hi-ai to ha yo-kai no hi-ai no koto nari [酉の火相とは夜会の火相のことなり]: the charcoal that the host has just laid will burn and heat the kama. The kama will come to a full boil, and then, as the fire wanes and collapses, it declines to a sub-boiling state. This is the desired condition for the hi-ai and yu-ai when the guests enter the room for the shoza of a night gathering -- and so it is the remains of the fire that was started at dusk (the Tori no hi-ai) that will serve as the shita-bi for the sumi-temae that is performed at the beginning of the yo-kai††.

In Shibayama Fugen’s teihon, the phrases of this sentence are inverted: yo-kai no hi-ai wo Tori no hi-ai to iu [夜會ノ火相ヲ酉ノ火相ト云], but the meaning is identical -- the hi-ai for the night gathering is provided by the fire that was established at dusk. ___________ *These are especially long hibashi (usually with the ends of the handles wrapped in a piece of bamboo sheath, held in place by loosely coiling a length of dark-green cord around it; the handles usually have rings on the end, and they were formerly attached to each other by a short chain, preventing the host from inadvertently dropping them) that allow the host to work in the ro for a prolonged time without exposing his hands to the intense heat that has accumulated between dawn and now. (The original ro-dan was made of mud-plaster, and this tends to become very hot, and continue to remain so even as the fire in the ro goes into a decline.)

†The way the charcoal is laid resembles the ordinary ro no sho-zumi temae [爐の初炭手前] as taught by the modern schools, with the only difference being that the guests are not present.

‡The kiri-wara [切り藁] is made from the outer leaf-sheaths of the sago palm (Cycas revoluta), rolled into a bundle and then bound with a series of copper wires. The lower end is frayed, and this is used to scour the bottom of the kama. Unlike other scouring tools, the kiri-wara causes minimal damage the surface of the iron -- though, even still, the host should restrict the scouring to the bottom and sides below the scar left where the top and bottom halves of the kama mold met.

**Mizu-kame [水甕] is a large, usually glazed ceramic, jar, with a wooden lid, in which the remaining water that was drawn at dawn is stored until needed later in the day.

††The sumi-temae performed during the shoza of the yo-kai is similar to what the modern schools teach as the ordinary ro no go-sumi-temae [爐の後炭手前], the abbreviated sumi-temae usually used when repairing the fire during the goza, between the koicha-temae and the usucha-temae.

Because Rikyū felt that, especially in the wabi setting, it was inappropriate to add charcoal to the fire more than once (indeed, he says that the estimation of the skill of the host is based on his ability to arrange the charcoal in such a way that the fire does not fail while the guests are still in the room, yet begins to decline slightly after the host concludes his usucha-temae -- indicating that there was only as much fuel used as needed), he preferred to serve usucha during the koicha-temae -- using the matcha that remained in the chaire as a way not only to save time (since the host would not have to go through the motions of cleaning a new tea container and the chashaku), but so he could use as much of the tea as possible while it was still fresh, so it would not go to waste (each time the tea was exposed to the air, its quality was felt to decline, so by the end of the gathering, the tea remaining in the chaire could never be used to serve guests on a subsequent occasion).

⁶Akatsuki ni nitaru-kokoro ari [曉ニ似タル心アリ].

Nitaru-kokoro [似たる心] means to have the same feeling* as (the hi-ai that was established at dawn).

The reason for this was explained under the previous footnote: the ro is emptied and cleaned, and then a new fire is established from scratch.

There are two important differences here, however. First, at dawn the interior of the ro is cold, while at dusk, the ro is very hot; and, while the dawn fire was started by arranging the charcoal on top of a bed of embers that was spread within the circle defined by the gotoku, here the remnants of the earlier fire are gathered into the center of the ro, with the charcoal laid around the periphery. As a result of the heat and the shimeshi-bai (which creates a strong updraft as it evaporates), the fire catches quickly, but burns more smoothly (because the charcoal is burning sideways, rather than from the bottom up).

The foundation of the Tori no hi-ai is a dō-sumi [胴炭]†, just as was the fire at dawn. And, also as at dawn, the kama is wet when it is lowered into the ro‡. __________ *This idiomatic use of kokoro is extremely difficult to translate into English. While the kanji itself means heart or mind, when used in this way it refers to a feeling, mood, mindset; or an imitation, some situation that imitates another. So a more accurate translation might be that (the laying of the fire at dusk to establish the Tori no hi-ai) mimics the laying of the fire at dawn.

†Please refer to the first sub-note under footnote 1 for details.

‡While this outwardly looks the same, however, the water in the kama is now at room temperature (which, even in the winter, in Japan, would be almost always well above freezing by late afternoon), meaning it is warmer than when first drawn from the well. As a result, the kama will boil faster than at dawn.

⁷Akatsuki no hataraki kokoro-e-beshi [曉ノハタラキ可心得].

Shibayama’s teihon includes a phrase at the beginning of this sentence which helps to qualify the rest: yū-sari yori kuru-kyaku ari, akasuki no hataraki kokoro-e-beshi [夕サリヨリ來ル客アリ、曉ノハタラキ可心得].

Yū-sari yori [夕去りより]: yū-sari refers to the time of day when the light in the sky begins to fade. The sun has dipped below the horizon, and, slowly, the sky darkens from blue to gray to purple. Yū-sari yori [夕去りより] means “from this time....”

Kuru-kyaku [來る客] means guests who have arrived (for a scheduled chakai). In other words, this is referring to the case where one (or more) of the guests who were invited to a night gathering have, unexpectedly, arrived early (usually with the intention of watching the host’s preparations).

Akatsuki no hataraki kokoro-e-beshi [曉の働き心得べし] means that (the host) should understand (kokoro-e-beshi [心得べし]) that the way things are done (hataraki [働き]) is the same as at dawn (akatsuki [曉 ]).

In other words, when guests come early, in order to watch the host establish the Tori no hi-ai, what he does (in front of their eyes) should be the same as if guests came at dawn.

At dusk, the fire in the ro has been burning constantly since dawn. Thus, before the host can set about laying the fire for the Tori no hi-ai, he first has to clean out the ro -- as was explained in detail, in the previous two footnotes. Because this is somewhat dangerous, the host needs to be able to concentrate on what he is doing without any possibility of distraction. Thus, even if the guest has arrived earlier, he must wait in the koshi-kake until the ro is cleaned, the select embers are arranged in the center of the ro, and the handa-hōroku (containing the rest of the burning charcoal, embers, and hot ash) has been removed to the mizuya. At this point, the ro is in the same basic state as it was at dawn, so it is from this time that the guest can enter the tearoom and watch the host’s preparation of the Tori no hi-ai.

It is important to point out that, while the guests might come early at dawn and at dusk, there is nothing comparable to this at noon, when the host establishes the Uma no hi-ai (the hi-ai that is established at noon), because at that time the ro is not cleaned out. Rather, at noon, the host simply brushing the white coating of ash off of the charcoal with the hibashi, and the remnant of the dawn’s dō-sumi [胴炭] is broken in half (if necessary -- though by this time, what remains of any of the pieces will be little more than a small ember*), and then moves all of the pieces together into the middle of the ro. After that he sprinkles some shimeshi-bai around the sides of the ro (to cover any bits of white ash, mostly to make things look tidy), and so arranges a set of charcoal around the pile of embers.

The Uma no hi-ai (as mentioned above) is based on a wa-dō [輪胴]. A wa-dō is similar to a gitchō [毬杖], but with a diameter that might be close to twice that of the average gitchō†. The rest of the "set" will consist of gitchō and gitchō that broke in half when being cut -- while the total number of pieces depends on the host's experience of what is necessary‡. ___________ *The host would not usually give more than one chakai on any given day (and, indeed, when following this practice as an exercise in the cultivation of ones samadhi, hosting a chakai would be more the exception, rather than the rule). Thus, when we speak about rebuilding the fire here, it is what remains of the dawn fire that the host would usually be dealing with, not the fire after a morning gathering.

†In Jōō’s and Rikyū’s period, the host usually cut the charcoal himself, starting with the 3-shaku long pieces that were purchased in bundles of 30 from the charcoal seller. As these were made from pine branches, the end that was attached to the trunk was usually considerably thicker than the other end. Two or three lengths of charcoal would usually yield enough cut pieces to fill the fukube.

A wa-dō was cut off the end of the thickest piece, and dō-sumi, were cut off the ends of the other pieces. Then, what remained were cut into gitchō (and since some of the gitchō usually break in half lengthwise during the cutting process, these provided the host with smaller pieces that could be used when the larger gitchō would be too much).

How much charcoal to use was a matter of experience -- and also depended on whether there would be an afternoon chakai or not. If there was not going to be an afternoon gathering, then the fire would be arranged to burn more slowly, so there would still be some larger embers left when the host went to establish the Tori no hi-ai at dusk.

‡Including whether this fire will be used as the shita-bi for a gathering that will be hosted in the middle of the afternoon, or whether the fire will have to last until dusk, to provide the shita-bi for the Tori no hi-ai that will be established at that time.

⁸Tori no koro ni hi-ai aratame, ro-chū sōji shitaru ato ni, tori ge-koku za-iri ha tsune no yo-kai betsu no koto nashi [酉ノ頃ニ火相アラタメ、爐中掃除シタルアトニ、酉下刻座入ハ常ノ夜會別ノコトナシ].

Tori no koro ni [酉の頃に] means around the Tori-no-koku [酉の刻] -- during the hour or so before dusk starts to fall*.

Ro-chū sōji shitaru ato ni [爐中掃除したる後に] means “after (ato ni [後に]) the interior of the ro (ro-chū [爐中]) has been cleaned (sōji shitaru [掃除したる])” -- this preparation of the ro includes the laying of the new set of charcoal, and the placing of the wet kama in the ro.

Tori gekoku za-iri [酉下刻座入] means (the guests) enter the room (during) the second half of the “Hour of the Rooster” (sometime between 6:00 and 7:00 PM)†. The sky is still fairly light at this time, but dusk will be falling. The availability of natural lighting is important so that the guests can see the arrangement of the tokonoma (which usually contains the chabana on this occasion). But it is important that the za-iri does not take place until after the kama has begun to decline‡ -- otherwise, when the host tries to repair the fire, he will end up putting in too much charcoal, meaning the kama will be in danger of boiling over (and the fire going out again before the service of usucha can be concluded).

Tsune no yo-kai betsu no koto nashi [常の夜会別のことなし] means nothing is different from an ordinary yo-kai other than the time that the guests enter the room. The biggest difference is that the availability of natural lighting means that the guests will be able to appreciate the chabana (which, as mentioned above, is usually displayed during the shoza at a yū-sari gathering), since after dark artificial lighting usually makes the flower arrangement hard to see clearly. __________ *The host should undertake the work of establishing the Tori no hi-ai while the sky is still quite light, so he can clearly see what he is doing. The Tori-no-koku [酉の刻] extends from 5:00 to 7:00 PM, with the sky growing perceptibly darker after the middle of this “hour” (that is, from around 6:00 PM -- though this actually differs depending on the time of year, since the koku [刻], “hours” vary in length depending upon the amount of light versus darkness on any given day).

†This is not an ordinary yo-kai [夜會] (night gathering), however, even though the details of the two gatherings are generally similar. This kind of chakai is sometimes titled the yū-sari-no-kai [夕去りの會].

While most of the details are the same, there is one big difference: at a yū-sari gathering, the chabana is usually displayed during the shoza, with the kakemono not being shown until the goza. Putting yin and yang philosophizing aside, the simple fact is that flowers always look best when viewed under natural light.

At a night gathering (but never at a yu-sari no kai), especially in the small room, the chabana (which, during this gathering, was generally displayed during the goza) was often replaced by a kake-tō-dai [掛け燈臺], a hanging oil-lamp suspended from the hook in the middle of the back wall of the tokonoma (during Jōō and Rikyū's period). Hanging the oil lamp in the toko in this way was called tō-ka [燈華] (“lamp-flower”), which is a pun on the word for flower (ka [華]), and the word for flame (ka [火]).

The tō-ka was one of Jōō’s greatest secrets -- and one that confuses most scholars even today (since the practice of suspending the oil lamp at the back of the toko is unknown to most of the modern schools).

Regarding the kake-tō-dai, the saucer of oil is placed on what looks like a wa-nashi ichi-jū-giri [��無し一重切], a bamboo ichi-jū-giri that lacks the ring of bamboo usually found above the mouth -- though, in this case, the lower part is reduced to a ring no thicker than necessary to support the saucer of oil safely (as can be seen in the photo). This detail (which made its first appearance during Rikyū’s last years) makes it resemble a flower arrangement even more -- with the flame taking the place of the flower.

‡The burning pieces of charcoal that remained from the Uma no hi-ai [午の火相] (the fire that was established at noon) should have crumbled into ash by the time that the guests are admitted to the room for the shoza of a yū-sari chakai. Therefore, during the sumi-temae, the host moves several pieces of burning charcoal from the periphery into the middle of the ro, and fills in the spaces with fresh gitchō [毬杖] from the fukube. The dō-sumi [胴炭] should still be reasonably intact, however, so it may be left in situ -- since turning it around, or breaking it in half (as is done during the sumi-temae at a yo-kai) will likely make the resulting fire burn too hotly, meaning the kama might boil over, and then start to fade too early as the fast-burning fire starts to go out.

These are things that cannot be understood except from years of experience performing chanoyu with a charcoal fire. They cannot be learned from books, or even from watching it done once or twice in keiko. The result has been the rise of the “electric” ro -- so that most modern chajin really do not know how to use charcoal any more.

⁹Sōji-mae-yori kite, yuru-yuru katatte, shita-bi yori shosa-shite miru-beki shomō no kyaku ari [掃除前ヨリ來テ、ユル〰語テ、下火ヨリ所作シテ見ルベキ所望ノ客アリ].

Sōji-mae-yori kite [掃除前より來て] means (the guests) arrive before (the host) begins to clean (the ro -- at dusk). In other words, it is their intention to watch the host establish the Tori no hi-ai*.

Yuru-yuru katatte [緩々語って] means to chat leisurely. This is referring to the behavior of the guests, if they decided to come early. Even if they entered the roji before the host started cleaning the ro, they should wait in the koshi-kake, chatting leisurely, until the host has finished the cleaning, and the shita-bi has been arranged in the ro, before making the request to be allowed to watch what the host is doing. They should never try to watch his cleaning of the ro.

Shita-bi yori shosa-shite miru-beki shomō no kyaku ari [下火より所作して見るべき所望の客あり]: there are guests (kyaku ari [客あり]) who ask to be allowed to watch (miru-beki shomō [見るべき所望]) the preparations (shosa-shite [所作して]) starting from the shita-bi (shita-bi yori [下火より]).

While, since the Edo period, it became customarily to submit this request to the host beforehand, in Jōō’s and Rikyū’s day it seems that the guest would just show up early -- around the time that he knew the host would have entered the tearoom to begin his preparations (this is why it says sōji-mae yori kite [掃除前より来て], arriving before the cleaning begins).

However, even though he arrived around the time when he imagined the host was going to begin his preparations, the guest would be left to wait in the koshi-kake until the host had finished taking out the fire, cleaning the ro, spreading fresh shimeshi-bai, inserting the shita-bi, and removing the handa-hōroku from the room -- because this part of the process is inherently dangerous (on account of the extreme flammability of just about everything in the tearoom), so the host must be allowed to concentrate on what he is doing and not be inadvertently distracted by the presence of a guest and his conversation.

This is why it says shita-bi yori...miru-beki shomō [下火より...見るべき所望], which means he asks to watch starting from the shita-bi (rather than starting with the cleaning that precedes the laying of the charcoal around the shita-bi). In other words, he is going to watch the host’s sumi-temae (which would resemble the modern schools’ sho-zumi [初炭] -- albeit with the wet kama not being brought out from the mizuya until after the charcoal had been arranged in the ro). __________ *The same thing was sometimes done at dawn, but the earliness of the hour, and the fact that most people prefer to remain in bed during that coldest hour before dawn breaks in winter, means that anyone with an inclination to spy out the host's lapses (just for the sake of doing so) would prefer to wait until a more reasonable hour. And late afternoon is certainly a more reasonable hour -- especially, if the guest was already planning to attend the night gathering, coming an hour or so early would not really be a problem, since he would have most likely had to close up shop in the early afternoon, so he could go home to bathe and dress for the chakai.

¹⁰Kōsha no teishu ni kanarazu kaku-no-gotoki-no-koto ari, akatsuki no gotoku nari [功者ノ亭主ニカナラズ如此ノコトアリ、曉ノゴトク也].

Kosha no teishu [功者の亭主] means a host who is fully matured; an host who has many years of experience.

Kaku-no-gotoki-no-koto [如此のこと] is referring to the case discussed in the previous footnote, where one (or all) of the guests comes early, in order to watch the host's preparations.

Akatsuki no gotoku nari [曉の如くなり] means “it is also the same at dawn.”

In other words, when the host is a man of great experience, it will be a wonderful opportunity -- that might not occur again -- for the guests to avail themselves of his experience by arriving early to watch him execute his preparations.

And while this should always be done in the case of a gathering that was scheduled for the evening, it is also an excellent reason for the guests to put comfort aside and get up early, and so present themselves at the host’s gate at dawn, so they can watch this master’s preparations for the day from the beginning.

¹¹Akatsuki mo yū-sari mo, za-no-kyō nakute ha machi-hisashiki mono naru yue, kōro nado dasu-koto tsune no koto nari [曉モ夕サリモ、坐ノ興ナクテハ待久シキモノナルユヘ、香爐ナド出スコト常ノコト也].

Za-no-kyō [座の興]* means amusement, entertainment.

Machi-hisashii-mono [待ち久しい] means in this situation (they must) wait for a long time.

In other words, whether the guests come at dawn, or to watch the host's establishment of the Tori no hi-ai at dusk, because there will be nothing to amuse them while waiting for the kama to begin to boil†, an incense burner should be brought out, so the guests can pass the time appreciating kyara [伽羅] incense‡. Then this can be stopped at an appropriate time so that the guests can finish eating the meal, and kashi, before the kama comes to a boil. __________ *The word would be zakyō [座興] today.

†In both of these situations, the host is starting with a kama filled with cold water. At dawn, the ro is cold, as is the water, so it will take even longer; but even at dusk, where the ro is hot and the water room temperature, the delay before tea can be served will be very long -- too long for just the simple “one-soup, three-dishes-of-cooked-vegetables” meal that was typical of Rikyū’s chakai (as well as those of Jōō’s latter period) to fill comfortably. Since this meal was intended to take no more than 15 minutes to eat, there will be quite a lot of time left.

It is in voicing this concern that we see how far modern-day chanoyu has diverged from the path laid down by Jōō and Rikyū. Because, taking their cue from the way things were done in Jōō's middle period (when everything was still based on the Shino family’s kō-kai [香會]), where the practice was to serve a meal based on the court banquet, the problem is not that there will be too much time, but that there will still not be time enough to serve everything, before the kama begins to sputter. This makes this entry difficult for modern scholars to explain in the context of their school’s vision of the chaji, even if they can understand the meaning of the words.

‡Since people of that time usually brought along some of their own favorite kyara, there will be enough to occupy them for 45 minutes to an hour, if necessary. After which the ordinary simple meal, and then kashi, can be served, bringing everything up to schedule.

Since the gathering was actually scheduled for the evening, it is not likely that the meal would have been ready at the conclusion of the sumi-temae in any case. Thus, appreciating incense will give the host (or his assistants) time to put the meal together while the kama slowly heats.

¹²Yojō-han ni te tanzaku・suzuri nado oite, shiika-tō kyaku ni yorite aru koto nari [四疊半ニテ短尺・硯ナド置テ、詩哥等客ニヨリテアルコトナリ].

Tanzaku・suzurinado oite [短冊・硯など置いて]: the tanzaku* are usually placed in a special lacquered box (made to match their dimensions). It was also conventional for the box to contain a mixture of tanzaku that were written by (usually famous†) poets as well as a selection of blank strips, on which the guests could choose to write their own poems; a suzuri [硯] is an inkstone, but usually the word refers to a writing box, which contained not only the stone, but a stick of ink, a water dropper, and one or several writing brushes. If the host suspected that something like a renga challenge would materialize, he would also provide a pack of writing paper and a low writing desk on which the person elected secretary could keep a record of the poems (and, sometimes, of the participants’ evaluation that was traditionally directed at each). Such varied things are covered by the word “nado” [など].

If the room had a built-in writing desk (a dashi fu-zukue [出し文机], or tsuke-shoin [付書院]), these things would be arranged there. Otherwise, they were placed out on the floor of the toko.

Shiika-tō [詩歌等]‡ means poetics, the practice of poetry; the act of composing poems.

The suggestion might be something like renga [連歌] (which was very popular at the time), where a number of people take part in the composition of a long poem. This is probably why this activity is reserved to the yojō-han, since the small number of guests in the sō-an would make the activity much less interesting (so it is unlikely that it would occupy the time between the end of the sumi-temae and the time when the simple meal was to be served).

This is naturally premised on whether the guests are interested in such activities or not. ___________ *Tanzaku [短冊] (tanzaku [短尺] is a mistake that was common during the period) are strips of decorative paper (usually imported from the continent) on which a single waka poem could be written. Each piece measures 1-shaku 2-sun by 2-sun.

†Or, in the case of Rikyū, poems written by Hideyoshi or prominent members of his court who had a poetic turn of mind (several men from noble families were found among his court, and both poetry and calligraphy were elements of their training). The precise nature of the poems depended both on the circumstances of the gathering (such as the time of year), and the specific guests who were invited.

‡Once again, shiika [詩哥], though commonly used during the sixteenth century, is a mistake. The word is correctly written shiika [詩歌].

¹³Teishu no nobe chiji-me kan-yō nari [亭主ノノベチヾメ肝要也].

Nobe-chijime [延べ縮め]: noberu [延べる] means to draw out, prolong; chijimeru [縮める] means to reduce, abridge.

Kanyō [肝要] means crucial, essential, very important.

In other words when the guests, having come early, are doing something to pass the time while waiting for the water to boil -- whether it is appreciating incense*, or composing renga† -- they can all too easily loose track of time. Therefore, the host (if nobody else) has to keep an eye on the kama, and either put a stop to the proceedings, or encourage the guests to indulge in one more round as the present situation demands, so that the meal and kashi (which will be served after the present activity is concluded) will be finished just as the kama begins to reach a low boil. Because, regardless of how delightful these other activities might be to all concerned, the purpose of the present gathering is chanoyu, and so its demands must take precedence over all else. __________ *Since the host would have prepared at least two varieties of kyara [伽羅] for the guests to enjoy, and each guest would probably have brought along one or two varieties of his own as a matter of course (people carried small pieces of incense wood in their right sleeve to perfume their breath, by holding a piece under their tongue, in those days before the advent of mouthwash; and, in the years before the forced segregation of the different arts became a rule in the Edo period, most cultured people became competent in at least several different interests: most of Jōō's original guests were people whom he had met at the Shino family’s kō-kai, and even in Rikyū’s day the majority of the people interested in chanoyu were also drawn from the same cultural pool). As a result, the appreciation of incense, once started, could easily continue for several hours if there were four or five guests in the room (remember, each variety of incense was traditionally passed around the room at least three times, so that each guest could appreciate all different stages of burning that quality incense exhibited -- with each round often ending with a discussion of the merits or flaws in the kyara that was just sampled).

†People interested in renga also tended to loose track of time -- especially when the gathering was not formally structured (this is why official renga-kai [連歌會] usually included the expected number of links in the invitation) -- since each guest composed his next poem based on something suggested by the previous participant’s poem.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 1 (27): the Fu-ji [不時] Gathering.

27) With respect to the fu-ji [不時] gathering¹, [the host] should certainly use [some of] his treasured utensils on such occasions² -- one, or even two, of which should be brought out³.

The way [the gathering] is “staged”⁴ should be “shin” [眞]⁵, while it is better if the mood⁶ is “sō” [草]⁷. [This is explained in] a kuden⁸.

_________________________

◎ Hizō-no-dōgu [秘蔵の道具] (treasured utensils): aka-chawan by Chōjirō, named “Shirasagi” [長次郎 の赤茶碗・“白鷺”]; chashaku by Kobori Enshū, named “Mushi-kui” [小堀遠州の茶杓・“虫喰”], ko-Takatori chaire, named “Utsumi” [古高取の茶入・“内海”].

¹Fu-ji no kai [不時の會].

This expression is usually explained (by the modern schools) today to mean a gathering that is held at other than the “usual” times*.

But, in Japanese, the word fu-ji [不時] means “unscheduled,” “unexpected,” “unforeseen,” and “uninvited.” And, according to Rikyū's kaiki, it seems that in his period this expression was used to mean a spontaneous, totally unplanned, chakai, at which only kashi were served (if the gathering happened to take place between mealtimes)†.

This entry seems to be another of those that were added during the early Edo period, since the specific teaching regarding the importance of using treasured utensils‡ goes against the details of what Rikyū did himself on the occasions that he labeled fu-ji [no kai]** -- and, indeed, doing so also implies a degree of pre-planning that circumstances suggest would have been impossible in the real-life examples quoted from the Hyakkai Ki. __________ *The “standard times” for chanoyu (according to the modern schools) are asa-cha [朝會] (in the morning), the shōgo-chaji [正午茶事] (at the noon hour), and the yo-kai [夜會] (in the evening).

Rikyū’s hiru-kai [晝會], which was his counterpart of the so-called shōgo-chaji, was more flexible in terms of the time at which the gathering could commence, since people did not customarily take a meal at midday during that period (this is reflected by the somewhat reduced fare mentioned as being served at these kinds of gatherings).

†These gathering seem to have actually been completely unplanned affairs, at which Rikyū used whatever utensils happened to be in the mizuya at the time, serving the guests the kinds of kashi that could be readied while the host performed the sumi-temae, and offering what would have been tea left over from the preparations for the previous chakai.

‡Since most people do not make a habit of leaving their valuables lying about the mizuya (if only because of the danger of their being accidentally broken), using such things implies that the host has received sufficient forewarning that he can consider his tori-awase carefully, and then go into the storehouse and start ferreting out these treasures. Rikyū‘s kaiki, however, suggest that nothing of the sort was possible, with respect to those chakai that he labeled as “fu-ji.”

**Two fu-ji kai are described in the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki [利休百會記]: on the last day of the Eleventh Month, and on the 15th day of the First Month. The kaiki for these gatherings, as recorded in that source, follow.

==============================================

❖ Onaji misoka ・ fu-ji ni [同晦日 ・ 不時に]

◦ yojō-han [四疊半]

◦ chanoyu mae no gotoku [茶湯まへのごとく] tadashi chaire mentori [但シ茶入めんとり]

◦ fuchidaka ni, kashi okoshi-kome, tawarako [ふちだかに、菓子 おこし米、たはらこ].

This means “the same [month], last day; [the gathering was] unscheduled; [the gathering was held in] the 4.5-mat room; the chanoyu was the same as before, though the chaire was [changed to] a mentori[-nakatsugi]; the kashi were served in a fuchi-daka: okoshi-kome, tawarako.”

The room was his detached 4.5-mat room, and the guests were four courtiers, for whom Hideyoshi may have had some private instructions or advice that he wished to be conveyed to their lord, which he offered to them via Rikyū.

At the previous chakai (which was at midday, suggesting that the fu-ji no kai was in the late afternoon), Rikyū used:

◦ kiri no kama [きりノ釜]

◦ Seto mizusashi [瀬戸水指]

◦ Sōho-dana [宗甫棚]

◦ Hikigi-no-saya [ひきゞのさや]

◦ chaire ・ Konoha-zaru [茶入・木の葉ざる]

◦ kane no mizu-koboshi [かねの水こぼし]

◦ Bizen tsubo [びぜんつぼ].

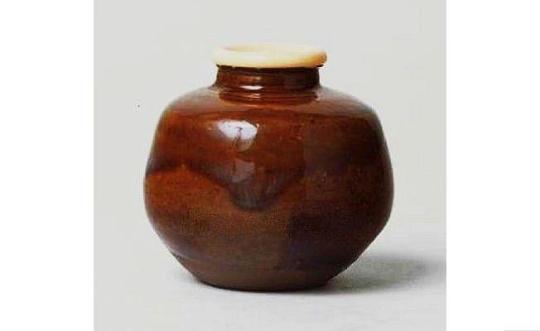

However, he notes that he substituted his tame-nuri mentori-nakatsugi [溜め塗面取中次], below, for the karamono Konoha-zaru chaire (thereby actually removing what had been the most treasured of the utensils that he had used at the earlier chakai):

◦ mentori [めんとり]

This mentori-nakatsugi was one of the containers in which either the excess tea (what remained after filling the chaire) was stored, or a container into which the chaire was emptied after the gathering (though such tea could not be used again to serve koicha, it could be used for usucha, and so it was preserved in a lacquered container that was as air-tight as possible).

Okoshi-kome [おこし米] is a sort of kashi made by mixing parched (“puffed”) rice with something like honey and then pressing this into a thick sheet, which was subsequently cut into more-or-less cubic or oblong pieces; tawarako [俵子] is sliced dried sea-cucumber, probably softened by boiling it briefly in broth.

==============================================

❖ Onaji jūgo-nichi ・ fu-ji [同十五日 ・ 不時]

◦ nijō-shiki [二疊敷]

◦ [arare-gama [あられ釜] -- the kama is not mentioned in this version of the kaiki, but it is elsewhere]

◦ wage-mizusashi [わげ水指]

◦ chaire ・ ko-natsume [茶入・小ナツメ]

◦ Ko-mamori no chawan [木守ノ茶碗]

◦ ori-tame [折撓]

◦ Hashi-date [はしだて]

◦ kashi ・ yaki-mochi, iri-kaya, shiidake [菓子 ・ やき餅、いりかや、しい竹].

This means “the same [month], fifteenth day; unscheduled; [the gathering was held in] the 2-mat room; wage-mizusashi, chaire ・ ko-natsume, Ko-mamori no chawan, ori-tame [chashaku], and the Hashi-date [cha-tsubo]; the kashi: yaki-mochi, iri-kaya, [and] shiidake.”

The guest was an advisor to the daimyō of Chiku-shū (in northern Kyūshū), to whom Rikyū was charged with delivering certain information for his lord, from Hideyoshi.

At this chakai, Rikyū changed the chaire (from his Shiri-bukura [���膨] to a small natsume), and also removed the objects (a Kokei scroll and meibutsu suzuri [硯]) that had been displayed in the tokonoma during the morning gathering.

As with the mentori-nakatsugi used during the previous fu-ji no kai, the small natsume was used either to preserve the matcha that was left over after filling the chaire for that morning's (scheduled) chakai, or was used as a receptacle into which the chaire was emptied at the end of that gathering (so the tea could be used later, to serve usucha).

Regarding the kashi, yaki-mochi [燒餅] is dried mochi that has been sliced into pieces and then toasted over a charcoal fire (which softens it) -- usually served on a skewer (by which it may be picked up and eaten, since it will be too hot to handle with the fingers); iri-kaya [煎り榧] are the roasted nuts of the Japanese allspice tree; and shiitake [椎茸] are lightly salted shiidake mushrooms that have been grilled over charcoal.

==============================================