#survey of british literature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Excerpt from this National Geographic story:

There are few animals so beloved in literature as the character of Ratty, one of the most endearing and widely quoted characters in Kenneth Graham’s children’s classic The Wind in The Willows.

Fans of the book will know of course that Ratty is not actually a rat but a water vole—a much cuter creature, with rich dark-brown fur, a bulbous nose, bright inquisitive eyes, and little furry ears tucked close to its head.

Back in 1908, when Wind in The Willows first appeared in print, water voles were a familiar sight along Britain’s riverbanks and canals, their distinctive “plop” as they as dived into the water as much a part of a river idyll as swans or birdsong.

But today things aren’t going quite so swimmingly. Water voles are Britain’s fastest disappearing mammal and face possible extinction. A recent wildlife survey showed an alarming 94 percent drop in water vole numbers from their healthy population of about 8 million of a century ago. Now listed as an endangered species in England and Wales, and threatened in Scotland, they have already vanished entirely from many parts of Britain.

Yet there’s reason to hope for these beloved animals: The voles’ decline, which has been gathering pace since the early 2000s, has prompted a flurry of reintroduction programs around the country to try to save Ratty—and in March the British government set aside £25 million (about U.S. $30 million) for restoring habitat for iconic wildlife such as water voles and otters.

“We’ve been so focused on otters over the years that I think we lost sight of what was happening with the voles,” says Paul Wilkinson, an ecologist with the Canal & River Trust, which has been rolling out miles of coir matting along the towpaths and riverbanks to encourage vole-friendly plant diversity. “Now otters are making a comeback, and it’s the voles we’re worried about.”

Like the character in the Wind in the Willows, water voles are model citizens, what ecologists call a keystone species, playing a role similar to that of beavers in helping to maintain a healthy wetland ecosystem.

Their burrowing and feeding activity aerates the soil, shifts seeds and nutrients, and helps to promote biodiversity, encouraging habitat for wildflowers, insects, reptiles, and amphibians.

On a less cuddly, but equally important note, they’re also natural prey for otters, foxes, pike and barn owls who have their own livings to make in Britain’s woodlands and waterways.

527 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello !! do u have any recommendations for books that demystify intelligence ? and/or historical analyses that pertain to its scientific construction ? I'm actually not picky at all, an extended reading list if you already have one available would be perfectly fine. I hope I'm being clear in my request bc English isn't my 1st language... if not, sorry

<3 bisou

for sure -- there's lots of writing about the historical context of IQ in particular, as well as other measures of 'intelligence' (binet-simon, galton, etc); there's also a lot of writing that's on specific national and regional contexts. so i'm not pulling anything close to an exhaustive list here lol but these are some i found at least somewhat helpful. im presuming you're a french speaker but if not just disregard the ones in french lol

The Mismeasure of Man by Stephen Jay Gould -- this is probably the no. 1 recommendation you will receive in english on this topic. it's not necessarily crucial if you've read other historical literature critiquing psychometry, but if not, it's a very solid text and is intended to be an easy entry point into the topic, so it can be a convenient place to start if you just need a leading-off point

‘The Intelligent and the Rest’: British Mensa and the Contested Status of High Intelligence (2020). Schregel, Susanne. History of the Human Sciences 33.5, 12-36. DOI: 10.1177/0952695120970029

Child prodigies in Paris in the belle époque: Between child stars and psychological subjects (2021). Graus, Andrea. History of Psychology 24.3, 255-274. DOI: 10.1037/hop0000192

Searching for South Asian Intelligence: Psychometry in British India, 1919--1940 (2014). Setlur, Shivrang. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 50.4, 359-375. DOI: 10.1002/jhbs.21692

La mesure de l'intelligence: Jeux des forces vitales et réductionnisme cérébral selon les anthropologues français (1860-1880) (1994). Blanckaert, Claude. Ludus Vitalis: Revista de Filosofía de las Ciencias de la Vida 2.3, 35-68

The Measure of Merit: Talents, Intelligence, and Inequality in the French and American Republics, 1750--1940 (2007). Carson, John S. Princeton University Press, ISBN: 0691017158

Ambiguities of Racial Science in Colonial Africa: The African Research Survey and the Fields of Eugenics, Social Anthropology, and Biomedicine, 1920--1940 (2005). Tilley, Helen. In Science across the European Empires, 1800--1950 (ed. Stuchtey, Benedikt. Oxford University Press, ISBN: 0199276292), pp. 245–287

Ribot, Binet, and the Emergence from the Anthropological Shadow (2007). Staum, Martin S. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 43, 1-18

La mesure en psychologie de Binet à Thurstone (1997). Martin, Olivier. Revue de Synthèse 118, 457-493

W. E. B. DuBois, Anthropometric Science, and the Limits of Racial Uplift (2006). Farland, Maria. American Quarterly 58, 1017-1044

The Mismeasure of Minds: Debating Race and Intelligence between Brown and The Bell Curve (2018). Staub, Michael E. University of North Carolina Press, ISBN: 9781469643595

After Binet: French intelligence testing, 1900-1950 (1992). Schneider, William H. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 28, 111-132

Woman's Brain, Man's Brain: Feminism and Anthropology in Late Nineteenth-Century France (2003). Sowerwinea, Charles. Women's History Review 12, 289-308

#book recs#there may also be a list of a few articles (like journalism not academic articles) tagged as either 'academia' or 'lit and literacy'

234 notes

·

View notes

Note

I would love to hear you talk about the overlooked history of vampire literature.....

the "vampires in gothic literature" episode of the podcast you're dead to me is the most comprehensive and accessible single look at the topic I've been able to find, but the thing that always annoys me the most in surveys of the history of vampire literature is that basically everyone forgets about all the poetry. there were a bunch of notable and popular english language poems featuring vampires before that famous lake geneva ghost story competition where byron spitballed the start of a vampire story that john polidori later expanded upon and published, and some of the big hitters include "thalaba the destroyer" (1801), "the vampyre" (1810), and "the giaour" (1813). also of note are "lenore" (1773) and "christabel" (1797), as even though neither explicitly contains vampires they both went on to be extremely influential on dracula and carmilla, respectively.

I believe there were also several notable early vampire poems in german, but my area of study is specifically british literature so that is a bit out of my wheelhouse, hence my focus on just english language stuff.

#the diction in christabel can be a bit difficult to get your head around if you aren't already quite familiar with Romantic poetry#but I really love it and definitely think it's worth giving a go if you're interested in perhaps Thee lesbian vampire blueprint#vampires#answered#anons

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

A MASTERLIST OF ALL THE BOOKS I COULD FIND IN TIM'S BOOKSHELVES

As someone who basically sees Tim Laughlin as my own version of Jesus Christ (I kind of wish I was lying but I have a 'beyond measure' tattoo branding my skin so perhaps I'm entirely serious), I simply needed to know what was on those shelves of his. And this was a hard task to achieve, believe me... but I got much farther than I initially thought I would.

(I've got so much to say about all of these books and how they might string together to create a deeper understanding of Tim as a character but I won't go into it here... maybe in a future post or video essay, who knows).

If you wish to help a girl out and attempt to figure out any of the other books I simply can not crack no matter how I look at the screenshots and mess with the adjustments... here's a folder full of 2k sized screenshots of those shelves.

Before I list the books one by one, I want to make a couple observations:

1) Almost all of the books I was able to pinpoint are non-fiction. The ones that aren't are children's books.

2) Topically, we see an interdisciplinary interest in:

History: from a book on a king in 4BC, to a survey of landholding in England in the 11th century.

Somewhat current historical events: books on World War I and II.

Western Philosophers: specially from the 16th to the 18th century.

Aesthetics: there's at least 2 books on the subject matter, but I couldn't find the second one, sadly.

Spirituality: not only christian/catholic; some of these books touch on Eastern practices such as Buddhism and Hinduism.

Fairy tales / children's books.

Psychology: specially in regards to mysticism and sexuality.

Science and scientific discovery/research.

3) A lot of the history, current events, and spirituality books are autobiographies/memoirs.

4) A lot of books (specially those on sciences and philosophy) tend to be more so anthologies or overviews on a subject matter rather than a book written by one specific author on one very concrete topic.

Overall, this all reflects very well an idea Jonathan Bailey himself expressed in a brilliant interview you can watch here if you haven't yet:

"Tim has buddhist flags in his 1980s flat in San Francisco, he has crystals, he is someone who is always seeking other ways to understand human experience. Which is probably tiring for him. Throughout the decades, he sort of appears as completely different people. At the crux of it there's this extreme grinding, contrasting, aggressive duality between feeling lovable and not feeling lovable. There's such shame in Tim. But it's the push and the pull which keeps him alive.”

This desire to understand human psychology, spirituality, and the ways of the universe through as many diverse lenses as possible, as well as a predilection for non-fiction, expresses very much to me that insatiable thirst for truth that defines his character so strongly.

OKAY, THAT BEING SAID. Here's the list in chronological order of publication.

PS. if you decided to click on any of the following titles it'd definitely not take you to a google drive link of the pdf file where you could download and read these books for yourself. Because that would be illegal and wrong.

Journeys through Bookland by Charles H. Sylvester (1901?) (1922 Edition)

I don't know which specific volume he owns, sorry, I tried my best but the number is not discernible (hell, the title barely is). If anyone wants the download link to these hmu because I'm not about to individually download all 10 right now.

10 volumes of poems, myths, Bible stories, fairy tales, and excerpts from children's novels, as well as a guide to the series. It has been lauded as ‘a new and original plan for reading, applied to the world’s best literature for children.’

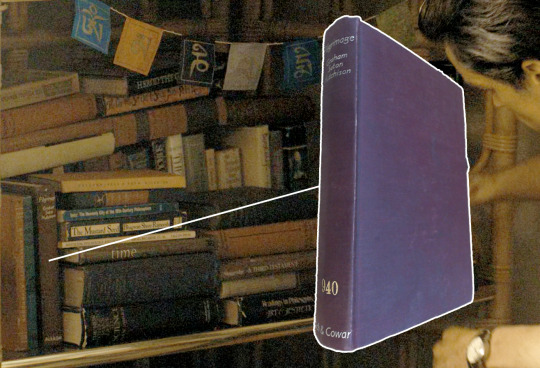

Pilgrimage by Graham Seton Hutchison (1936)

This book provides a view of the battlefields of WW I through the eyes of the average fighting man.

One curious thing about this book is that it's author, a British First World War army officer and military theorist, went on to become a fascist activist later in his life. Straight from Wikipedia:

"Seton Hutchison became a celebrated figure in military circles for his tactical innovations during the First World War but would later become associated with a series of fringe fascist movements which failed to capture much support even by the standards of the far right in Britain in the interbellum period." He made a contribution to First World War fiction with his espionage novel, The W Plan."

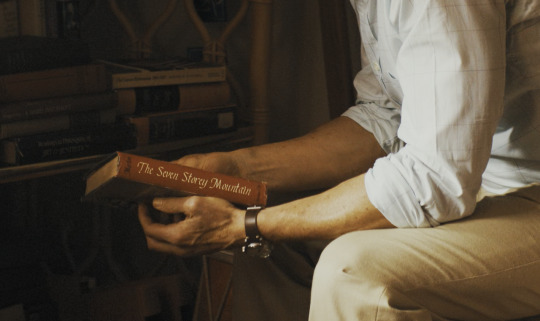

The Seven Storey Mountain by Thomas Merton (1948)

The Seven Storey Mountain tells of the growing restlessness of a brilliant and passionate young man, who at the age of twenty-six, takes vows in one of the most demanding Catholic orders—the Trappist monks. At the Abbey of Gethsemani, "the four walls of my new freedom," Thomas Merton struggles to withdraw from the world, but only after he has fully immersed himself in it. At the abbey, he wrote this extraordinary testament, a unique spiritual autobiography that has been recognized as one of the most influential religious works of our time. Translated into more than twenty languages, it has touched millions of lives.

This book requires no introduction. It's the one he keeps the Fire Island's postcard in and the one we see him re-reading in episode 8 after Hawk brings it to the hospital with him at the end of episode 7.

Just a little detail I noticed:

Apparently he liked the book so much he visited Gethsemani, which was the home of its author all the way up till 1968.

For all we know, he might have even met its author!

Sexual Behavior in the Human Male by Alfred Charles Kinsey, Wardell B. Pomeroy (1948)

When published in 1948 this volume encountered a storm of condemnation and acclaim. It is, however, a milestone on the path toward a scientific approach to the understanding of human sexual behavior. Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey and his fellow researchers sought to accumulate an objective body of facts regarding sex. They employed first hand interviews to gather this data. This volume is based upon histories of approximately 5,300 males which were collected during a fifteen year period. This text describes the methodology, sampling, coding, interviewing, statistical analyses, and then examines factors and sources of sexual outlet.

Yes, Charles Kinsey is indeed behind the Kinsey scale that has done so much for the LGBTQ+ community.

Their Finest Hour (1949), The Grand Alliance (1950), and Closing the Ring (1951) by Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill's six-volume history of the cataclysm that swept the world remains the definitive history of the Second World War. Lucid, dramatic, remarkable both for its breadth and sweep and for its sense of personal involvement, it is universally acknowledged as a magnificent reconstruction and is an enduring, compelling work that led to his being awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1953.

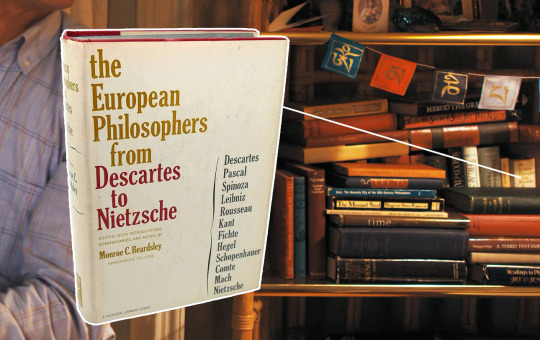

The European Philosophers from Descartes to Nietzsche by Monroe C. Beardsley (1960)

In so far as we reflect upon ourselves and our world, and what we are doing in it, says the editor of this anthology, we are all philosophers. And therefore we are very much concerned with what the twelve men represented in this book--the major philosophers on the Continent of Europe--have to say to us, to help us build our own philosophy, to think things out in our own way. For the issues that we face today are partly determined by the work of thinkers of earlier generations, and no other time is more important to the development of Western thought than is the 250-year period covered by this anthology. Monroe. C. Beardsley, Professor of Philosophy at Swarthmore College, has chosen major works, or large selections from them, by each man, with supplementary passages to amplify or clarify important points. These include: Descartes - Discourse on Method (Descartes), Thoughts (Pascal), The Nature of Evil (Spinoza), The Relation Between Soul and Body (Leibniz), The Social Construct (Rousseau), Critique of Pure Reason (Kant), The Vocation of Man (Fichte), Introducciton to the Philosophy of History (Hegel), The World as Will and Idea (Schopenhauer), A General View of Positivism (Comte), The Analysis of Sensations and the Relation of the Physical to the Psychical (Mach), Beyond Good and Evil (Nietzsche).

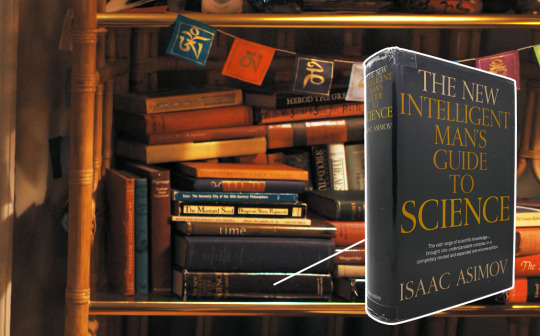

The New Intelligent Man's Guide to Science by Isaac Asimov (1965)

Asimov tells the stories behind the science: the men and women who made the important discoveries and how they did it. Ranging from Galilei, Achimedes, Newton and Einstein, he takes the most complex concepts and explains it in such a way that a first-time reader on the subject feels confident on his/her understanding. Assists today's readers in keeping abreast of all recent discoveries and advances in physics, the biological sciences, astronomy, computer technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and other sciences.

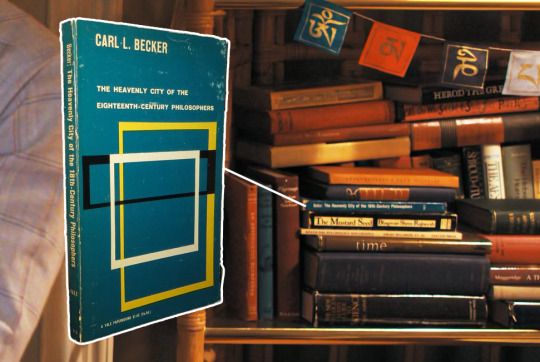

The Heavenly City of the 18th Philosophers by Carl L. Becker (1932) (1962 reprint)

Here a distinguished American historian challenges the belief that the eighteenth century was essentially modern in its temper. In crystalline prose Carl Becker demonstrates that the period commonly described as the Age of Reason was, in fact, very far from that; that Voltaire, Hume, Diderot, and Locke were living in a medieval world, and that these philosophers “demolished the Heavenly City of St. Augustine only to rebuild it with more up-to-date materials.” In a new foreword, Johnson Kent Wright looks at the book’s continuing relevance within the context of current discussion about the Enlightenment.

I find the particular choice of adding this book very curious and on brand, since it explores the idea that philosophers of the Enlightenment very much resembled religious dogma/faith in their structure and purpose. Just... A+ of the props department to not just add any kind of book on philosophy anthology.

Herod The Great by Michael Grant (1971)

The Herod of popular tradition is the tyrannical King of Judaea who ordered the Massacre of the Innocents and died a terrible death in 4 BC as the judgment of God. But this biography paints a much more complex picture of this contemporary of Mark Antony, Cleopatra, and the Emperor Augustus. Herod devoted his life to the task of keeping the Jews prosperous and racially intact. To judge by the two disastrous Jewish rebellions that occurred within a hundred and fifty years of his death -- those the Jews called the First and Second Roman Wars -- he was not, in the long run, completely successful. For forty years Herod walked the most precarious of political tightropes. For he had to be enough of a Jew to retain control of his Jewish subjects, and enough of a pro-Roman to preserve the confidence of Rome, within whose territory his kingdom fell. For more than a quarter of a century he was one of the chief bulwarks of Augustus' empire in the east. He made Judaea a large and prosperous country. He founded cities and built public works on a scale never seen before: of these, recently excavated Masada is a spectacular example. And he did all this in spite of a continuous undercurrent of protest and underground resistance. The numerous illustrations presents portraits and coins, buildings and articles of everyday use, landscapes and fortresses, and subsequent generations' interpretations of the more famous events, actual and mythical, of Herod's career.

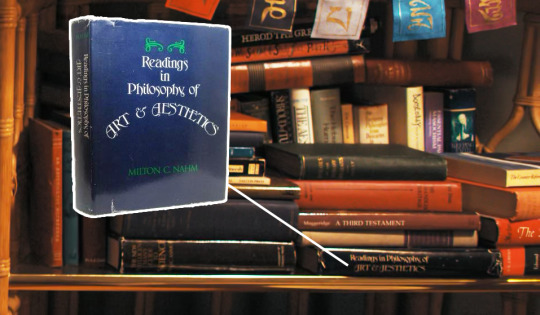

Readings in the Philosophy of Art and Aesthetics compiled by Milton Charles Nahm (1975)

A college level comprehensive anthology of essays written on the arts and the field of aesthetic philosophy.

The Mustard Seed: Discourses on the Sayings of Jesus Taken from the Gospel According to Thomas by Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (1975)

This timely book explores the wisdom of the Gnostic Jesus, who challenges our preconceptions about the world and ourselves. Based on the Gospel of Thomas, the book recounts the missing years in Jesus’ life and his time in Egypt and India, learning from Egyptian secret societies, then Buddhist schools, then Hindu Vedanta. Each of Jesus' original sayings is the "seed" for a chapter of the book; each examines one aspect of life — birth, death, love, fear, anger, and more — counterpointed by Osho’s penetrating comments and responses to questions from his audience.

(You don't know how fulfilling it was to find some of these books and just sit there like "oh my god, yessss, he'd SO read that".)

A Third Testament by Malcolm Muggeridge (1976)

A modern pilgrim explores the spiritual wanderings of Augustine, Pascal, Blake, Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Bonhoeffer. A Third Testament brings to life seven men whose names are familiar enough, but whose iconoclastic spiritual wanderings make for unforgettable reading. Muggeridge's concise biographies are an accessible and manageable introduction to these spiritual giants who carried on the testament to the reality of God begun in the Old and New Testaments. - St. Augustine, a headstrong young hedonist and speechwriter who turned his back on money and prestige in order to serve Christ - Blaise Pascal, a brilliant mathematician who pursued scientific knowledge but warned people against thinking they could live without God - William Blake, a magnificent artist-poet who pled passionately for the life of the spirit and warned of the blight that materialism would usher in - Soren Kierkegaard, a renegade philosopher who spent most of his life at odds with the church, and insisted that every person must find his own way to God - Fyodor Dostoevsky, a debt-ridden writer and sometime prisoner who found, in the midst of squalor and political turmoil, the still small voice of God - Leo Tolstoy, a grand old novelist who swung between idealism and depression, loneliness and fame and a duel awareness of his sinfulness and God s grace - Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a pastor whose writings and agonized involvement in a plot to kill Hitler cost him his life, but continue to inspire millions

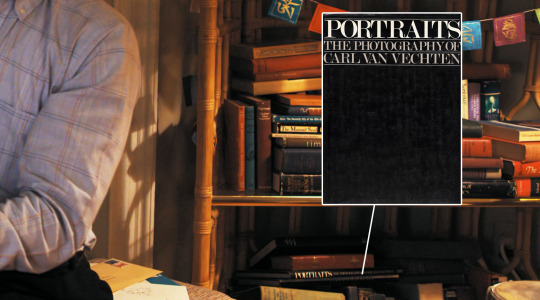

Portraits: The photography of Carl Van Vechten (1978)

Can't find a file but you can borrow it from archive.com in the link provided.

During his career as a photographer, Carl Van Vechten’s subjects, many of whom were his friends and social acquaintances, included dancers, actors, writers, artists, activists, singers, costumiers, photographers, social critics, educators, journalists, and aesthetes. [...] As a promoter of literary talent and a critic of dance, theater, and opera, Carl Van Vechten was as interested in the cultural margin as he was in the day’s most acclaimed and successful people. His diverse subjects give a sense of both Carl Van Vechten’s interests and his considerable role in defining the cultural landscape of the twentieth century; among his many sitters one finds the leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance, the premier actors and writers of the American stage, the world’s greatest opera stars and ballerinas, the most important and influential writers of the day, among many others.

Report of the Shroud of Turin by John H Heller (1983)

Heller, while a man of science, was nevertheless a devout man (Southern Baptist). He viewed his task concerning The Shroud with great scepticism; there have been far too many hoaxes in the world of religion. The book describes in great detail the events leading up to the team's conviction that the Shroud was genuine; last - not least - being Heller and Adler's verification of "heme" (blood) and the inexplicable "burned image" of the crucified man. Although carbon dating indicates that the image is not 2000 years old and that the cloth is from the Middle Ages, there is not enough evidence to disprove Heller's assertion that the Shroud is indeed genuine.

Context for those who may not know (though I doubt it's necessary): The shroud of Turin "is a length of linen cloth that bears a faint image of the front and back of a man. It has been venerated for centuries, especially by members of the Catholic Church, as the actual burial shroud used to wrap the body of Jesus of Nazareth after his crucifixion, and upon which Jesus's bodily image is miraculously imprinted."

It is a very controversial subject matter and I definitely don't know that from going to an Opus Dei school since the day I was born till the day I graduated high school.

Mysticism, Psychology and Oedipus by Israel Regardie (1985)

I've tried my hardest but despite many Israel Regardie books being on the world wide web, I can't find a copy of this specific one.

Mysticism, Psychology and Oedipus, from the Small Gems series is one of these mysterious alchemys which Regardie and Spiegelman crafted for the serious student of mysticism. Mysticism, Psychology and Oedipus by Dr. Israel Regardie and his friend, world renowned Jungian Psychologist, J. Marvin Spiegelman, Ph.D. was created to reach the serious student at the intersecting paths of magic, mysticism and psychology. While each area of study overlaps they also maintain their own individual paths of truth. One of Regardie’s greatest gifts was his rare ability to combine these difficult and diverse subjects and make them understandable.

Domesday Book Through Nine Centuries by Elizabeth M. Hallam (1986)

In 1086 a great survey of landholding in England was carried out on the orders of William the Conqueror, and its results were recorded in the two volumes, which, within less than a century, were to acquire the name of Domesday, or the Book of Judgment 'because its decisions, like those of the last Judgment, are unalterable'. This detailed survey of the kingdom, unprecedented at that time in its scope, gives us an extraordinarily vivid impression of the life of the eleventh century.

The following two are a fuck up on the props department part because they were published after 1987 but we'll forgive them because they were not expecting for me to do all this to figure out the titles of these books, I'm sure:

The One Who Set Out to Study Fear by Peter Redgrove (1989)

This book barely exists physically, rest assured it does not exist online... LOL.

The author of The Wise Wound presents here a re-telling of Grimm's famous fairy tales, written in a manner and spirit more suited to the present day. Each story is rooted in the original, but cast in an energetic style that is both disrespectful and humorous.

Essential Papers on Masochism by Margaret Ann Fitzpatrick Hanly (1995)

The contested psychoanalytic concept of masochism has served to open up pathways into less-explored regions of the human mind and behavior. Here, rituals of pain and sexual abusiveness prevail, and sometimes gruesome details of unconscious fantasies are constructed out of psychological pain, desperate need, and sexually excited, self- destructive violence. In this significant addition to the "Essential Papers in Psychoanalysis" series, Margaret Ann Fitzpatrick Hanly presents an anthology of the most outstanding writings in the psychoanalytic study of masochism. In bringing these essays together, Dr. Fitzpatrick Hanly expertly combines classic and contemporary theories by the most respected scholars in the field to create a varied and integrated volume. This collection features papers by S. Nacht, R. Loewenstein, Victor Smirnoff, Sigmund Freud, Jacques Laplanche, Robert Bak, Leonard Shengold, K. Novick, J. Novick, S. Coen, Margaret Brenman, Esther Menaker, S. Lorand, M. Balint, Bernhard Berliner, Charles Brenner, Helene Deutsch, Annie Reich, Marie Bonaparte, Jessica Benjamin, S.L. Olinick, Arnold Modell, Betty Joseph, and Janine Chasseguet-Smirgel.

Let's not forget another book we know has been present in his shelves at some point:

Look Homeward, Angel by Thomas Wolfe (1929)

It is Wolfe's first novel, and is considered a highly autobiographical American coming-of-age story. The character of Eugene Gant is generally believed to be a depiction of Wolfe himself. The novel briefly recounts Eugene's father's early life, but primarily covers the span of time from Eugene's birth in 1900 to his definitive departure from home at the age of 19. The setting is a fictionalization of his home town of Asheville, North Carolina, called Altamont in the novel.

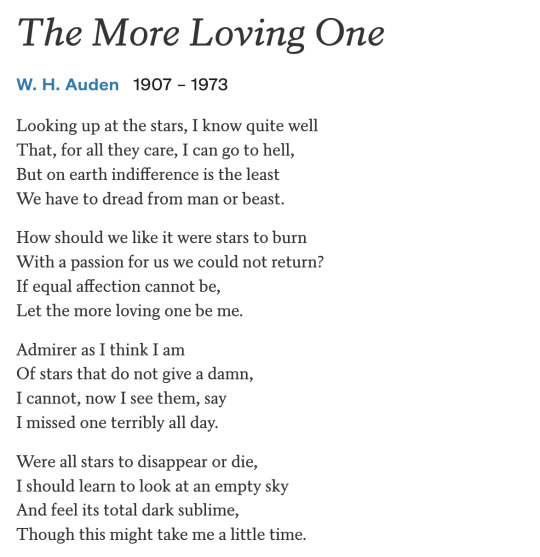

And Ron Nyswaner mentioned in a podcast (might be this one? I'm not sure) that he scrapped from the script a line where Tim recommends this poem at some point:

He specially emphasized the line "If equal affection cannot be, Let the more loving one be me".

And lastly, if anyone wanted to know:

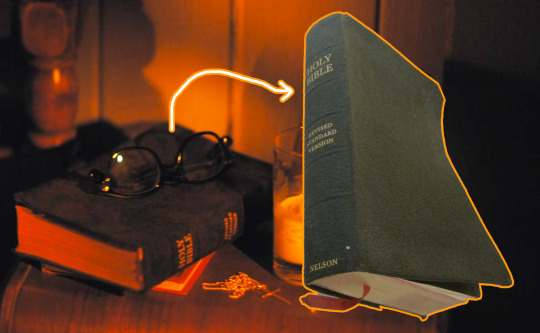

His copy of the bible is the Revised Standard Version by Thomas Nelson from either 1952 or 1953.

Because why the hell not figure out what specific translation of the holy bible a fictional character was basing his beliefs on — as if the set designers cared nearly as much as I do.

#fellow travelers#fellow travelers meta#tim laughlin#fellowtravelersedit#i know it doesnt precisely fit the tag but hey.. theres a gif right there#this is such a jobless thread... but i AM jobless

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

something that annoys me about anti-swifties is prior to the release of TTPD when the track list dropped someone said “yall, she has a song called down bad and loml. she is not as deep as yall like to believe” and just tell me you’ve never studied any form of literature seriously. because all the poets and writers we think of today who have deep and meaningful texts that we must study did not write it for that reason back in the day.

my entire survey of early british literature class was mainly just my professor trying to deconstruct our idea of what classic literature was and show us it was still modern and relevant and that it was raunchy and proactive at times too. like she had us read select passages from the faerie queen and when she told us the plot between several parts cause we were jumping she dropped so many bombs that after she was done every hand shot up with a different question about a different part (mine was on the giant penis that haunted red cross knight after he had premarital sex if you were curious).

so like… yeah the titles aren’t that deep cause it’s modern slang but you’re all going to be shocked to learn that a lot of older literature had slang both in them and as their titles! i hate to break it to you but you know jack shit about literature and what it means.

also this isn’t me saying you have to think her songs are deep and meaningful. because it depends on what you feel and interpret the songs as. you dont have to like the songs. but if you’re going to woefully misunderstand them to paint someone out as a villian with actual zero evidence, i worry about your reading comprehension skills and media literacy as a whole. because to make big ass declarations when you have zero knowledge of literature is very fucking telling.

#this isn’t also me saying#they are deep#but man the lot of yall know jack shit about literature and are acting like fucking police over it#kelly babels#taylor swift

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Woah. Not exaggerating: The very same week you tagged me here, I was submitting a final draft paper about spectacle and British use of animal imagery and caricatures of South Asian resistance, especially on stages and in "ethnographic" exhibitions. Part of this involved the weaponization of spectacle, media, and public display. And part of this involved British imagination of "exotic" animals. And the article shown here kinda invokes both of those subjects.

That afternoon, I had been reading through a 2012 article with new-to-me info about the staging of theatre-esque mass trials/executions of Thugee by British administrators 1820s-1850s. (More on that below.)

In the pictured article/link shown here, similarly, Shanahan describes fig trees and mass hangings of Indian rebels. He lists about a dozen instances of when British authorities used fig trees to perform quasi-ritualized mass executions between 1806 and 1871.

Among them, he notes two in particular:

1857, hanging 144 rebels from a single tree in Nanaro Park at Kanpur (Shanahan cites a T!mes of !nd!a article, which itself cites a history department professor at Christ Church College)

March 1860, hanging 257 rebels from a single tree in Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, in retaliation for their revolt in May/June 1857, when rallying under Khan Bahadur Khan (Shanahan again cites T!mes of !nd!a, who cite an ancient history and culture professor at Mahatma Jyotiba Phule Rohilkhand University)

---

The same afternoon you tagged me, I was straight-up reading:

Maire ni Fhlathuin, "Staging Criminality and Colonial Authority: The Execution of Thug Criminals in British India." Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film, Volume 37, Issue 1, October 2012.

She "examines the staging and response to the public executions of thugs, focusing on the British authorities' 'scripting' of the execution ritual (as documented in East India Company records and the writings of the officials involved) to include [...] the crowd's appreciation of the eradication of that criminality."

---

British animalization and/or dehumanization in depictions of South Asia, what they both call "interspecies/multispecies empire," more directly explored by Rohan Deb Roy (insects/bugs in India) and Jonathan Saha (elephants/cattle in Burma). But another thing I had been referencing in my own little paper was British fixation on re-enacting the defeat of Indian rebels, which you might especially notice in stage plays about Tipu Sultan (the "Tiger of Mysore" beaten by "the British bulldog," defeated in 1799, who became the central villain/character of multiple spectacular and popular plays in London from 1790s-1830s, to such an extent that British schoolchildren decades later would still understand references to villianous "Tipu"; and historian Daniel O'Quinn, who's written much about British popular discourses about crises in the Age of Revolutions, called the plays comparable to "precinema"; after his defeat, the East India Company could secure sandalwood resources and perform sweeping cartographic surveys for land/revenue administration). Probably worth noting nineteenth-century Britain played host to the explosion of newly-affordable mass-market print media of all kinds; recalcitrant South Asian rebels show up in stage, sportsmen's magazines, travel literature genre, novels, etc.

On the subject of weaponizing newly-emergent media, the author linked/pictured here (Shanahan) too, also lists in his bibliography:

Sean Willcock. "Aesthetic Bodies: Posing on Sites of Violence in India, 1857-1900." History of Photography, Volume 39 (2015), Issue 2, pages 142-159.

Abstract includes: "This article looks at how aesthetic concerns inflected the dynamic of imperial relations during the 1857 Indian Uprising and its aftermath. The invention of photography inaugurated a period in which aesthetic imperatives increasingly came to structure the engagement of colonial bodies with the traumas of warfare in British India. The formal conventions of image-making practices were not consigned to a discreet virtual sphere; they were channelled into the contested terrains of the subcontinent through the poses that figures were striking for the camera. I trace how one pictorial convention - picturesque staffage - had the capacity to engender politically and psychologically disruptive tableaus on the contested terrains of empire, as colonial photographers arranged for Indian figures to pose on landscapes that were marked by disturbing wartime violence."

---

And finally, another of his citations includes:

Kim A Wagner. "'Calculated to Strike Terror': The Amritsar Massacre and the Spectacle of Colonial Violence." Past & Present, Volume 233, Issue 1, November 2016, pages 185-225.

And in her article, Wagner describes:

"Closely following the ritual model provided by judiciary practices in the imperial homeland, the British in India nevertheless favoured hanging [...] Controlling the symbolism of public executions, however, proved increasingly difficult within a colonial context, and the hanging of hundreds of highway robbers known as Thugs during the 1830s had fully exposed the porous nature of colonial rituals of power. The Thugs signally failed to conform [...]. [T]hey [...] climbed the scaffold and [...] tightened the noose around their own neck and then simply stepped off the platform [...]. As regiment after regiment broke out in mutiny across northern India during the summer of 1857, [...] the colonial state thus unleashed its entire arsenal of exemplary violence. [...] [A]nd it was in that context that the first mass execution of forty sepoys by cannon had been ordered in Peshawar on 13 June 1857 [...]. This was only the first of many such mass executions [...]. A contemporary British newspaper report elaborated on the cultural specificity of the ritual enacted in Peshawar: You must know that this is nearly the only form in which death has any terrors for a native … he knows that his body will be blown into a thousand pieces, and that it will be altogether impossible for his relatives, however devoted to him, to be sure of picking up all the fragments of his own particular body [...]. Execution by cannon could thus be presented as both justified and civilized or, as Lord Roberts put it, ‘Awe inspiring, certainly, but probably the most humane, as being a sure and instantaneous mode of execution’. [...] In the House of Commons, Lord Stanley expressed this sentiment in no uncertain terms: ‘Only by great exertions - by the employment of force, by making striking examples, and inspiring terror, could Sir J. Lawrence save the Punjab; and if the Punjab had been lost the whole of India would for the time have been lost with it’.

---

I do kinda wonder if, sometimes, contemporary people, today, might think: "Well, maybe we're unfairly retroactively ascribing motivations of malice to nineteenth-century imperial administrators. And even if they were sometimes spiteful or horrifically violent to that extent, surely they probably exercised discretion; they couldn't have been too explicit." But then you read about them performing executions by shooting cannonballs at groups of people. Or you read the words of major popular, industrial, or political figures casually describing this kind of thing when speaking directly to the public, the newspapers, or the House of Commons (you can read plenty more scary, explicit comments like this from other officials and administrators in all kinds of institutions).

As Shanahan describes here in "Trees of life that became agents of death," British administrators (and media in the metropole, too) whether deliberately or otherwise, manipulated or employed animals and plants in the popular conciousness; whole bunch of writing elsewhere about British fixation on "man-eating" tigers, lions, crocodiles, mosquitoes, flies, etc., and appropriating creatures (like appropriating fig trees in Shanahan's reading). Or idealization of the same and other creatures, like celebrating rubber, sugarcane, elephants, etc. Dovetails with long history of picturing and/or harnessing "tropical nature" in US, British, and European imaginaries.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Below are 10 articles from Wikipedia's featured articles list. Links and descriptions are below the cut.

On Saturday, May 1, 1920, the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Boston Braves played to a 1–1 tie in 26 innings, the most innings ever played in a single game in the history of Major League Baseball. Both Leon Cadore of Brooklyn and Joe Oeschger of Boston pitched complete games, and with 26 innings pitched, jointly hold the record for the longest pitching appearance in MLB history.

Clarence 13X, also known as Allah the Father (born Clarence Edward Smith) (February 22, 1928 – June 13, 1969), was an American religious leader and the founder of the Five-Percent Nation, sometimes referred to as the Nation of Gods and Earths.

Henry Edwards (27 August 1827 – 9 June 1891) was an English stage actor, writer and entomologist who gained fame in Australia, San Francisco and New York City for his theatre work.

The law school of Berytus (also known as the law school of Beirut) was a center for the study of Roman law in classical antiquity located in Berytus (modern-day Beirut, Lebanon). It flourished under the patronage of the Roman emperors and functioned as the Roman Empire's preeminent center of jurisprudence until its destruction in AD 551.

Minnie Pwerle (also Minnie Purla or Minnie Motorcar Apwerl; born between 1910 and 1922 – 18 March 2006) was an Australian Aboriginal artist. Minnie began painting in 2000 at about the age of 80, and her pictures soon became popular and sought-after works of contemporary Indigenous Australian art.

Ove Jørgensen (Danish pronunciation: [ˈoːvə ˈjœˀnsən]; 5 September 1877 – 31 October 1950) was a Danish scholar of classics, literature and ballet. He formulated Jørgensen's law, which describes the narrative conventions used in Homeric poetry when relating the actions of the gods.

Legends featuring pig-faced women originated roughly simultaneously in The Netherlands, England and France in the late 1630s. The stories tell of a wealthy woman whose body is of normal human appearance, but whose face is that of a pig.

The Private Case is a collection of erotica and pornography held initially by the British Museum and then, from 1973, by the British Library. The collection began between 1836 and 1870 and grew from the receipt of books from legal deposit, from the acquisition of bequests and, in some cases, from requests made to the police following their seizures of obscene material.

Qalaherriaq (Inuktun pronunciation: [qalahəχːiɑq], c. 1834 – June 14, 1856), baptized as Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua, was an Inughuit hunter from Cape York, Greenland. He was recruited in 1850 as an interpreter by the crew of the British survey barque HMS Assistance during the search for John Franklin's lost Arctic expedition.

Sophie Blanchard (French pronunciation: [sɔfi blɑ̃ʃaʁ]; 25 March 1778 – 6 July 1819), commonly referred to as Madame Blanchard, was a French aeronaut and the wife of ballooning pioneer Jean-Pierre Blanchard. Blanchard was the first woman to work as a professional balloonist, and after her husband's death she continued ballooning, making more than 60 ascents.

#Wikipedia polls#people said they liked the summaries-first format but it got fewer votes in total so i think I'll stick with summaries-after-the-cut#i would recommend checking out the readmore before you vote though. or don't I'm not your boss

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

interview with the vampire art history lesson part 2:

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, Francis Bacon, c. 1944. Held at the Tate Britain in London. Here is its catalog listing.

So! This is the painting that has been on the wall of Louis and Armand's apartment, and that Season 2 makes a point to emphasize that they're selling. Full disclosure, modern British art history is not my forte, but I have covered this in a British art history survey class, and this is arguably one of Bacon's most famous works, so there's a lot of literature you can find on this. Let's discuss!!!

Now, one claim that you can try to make here about the relationship of this painting with Armand specifically is that Armand is now connected to two 'Christian' artworks (see my post on The Adoration of the Shepherds with a Donor here): one that marks the beginning of Christ's (semi)mortal life, and one that marks the end of it, which is definitely interesting, but the thing is with this Three Studies piece is that Francis Bacon put a lot of emphasis on the fact that this is a crucifixion, not the Crucifixion. Francis Bacon was an atheist, however, a lot of his work does revolve around either critiquing or dealing with Christianity (this is not his only work to reference/allude to or show the Crucifixion, as well as his other very famous work, Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X). It was a very nuanced, complex topic for him that is way beyond the scope of this post.

Interestingly, though, Bacon has made a point to say that "faith is a fantasy" [1]----which is definitely something interesting in relation to Armand...

What Three Studies is definitely associated with, though, is World War II and Greek tragedy.

The catalog entry from the Tate spends a while discussing the process of this painting, and how Bacon may have drawn from his various experiences during World War II (he was in the ARP during the London Blitz), as well as other works made around this time (namely, Figure Getting Out of a Car and Man in a Cap) referencing various Nazi imagery that Bacon had seen impacting his process for creating this triptych. Various scholars have cited Bacon as interested in the dynamics of power and violence, and the imagery of the triptych can be interpreted as either the perpetrator and/or the victim [2]. Bacon has also confirmed that this painting references the Eumenides (the Furies who are responsible for enacting revenge in Greek mythology) [3 + 4].

Now that we've covered the very basics of this work, let's discuss how this might relate to Louis and Armand. This work being present in the show has raised some interesting points for me, and some questions:

The show makes a point of emphasizing that they're selling this work. Since this work is so closely related to World War II, and Louis and Armand are currently trying to relay their experiences during World War II, is the selling of it symbolic of either 1) 'selling' their story to Daniel or 2) finally closing out that chapter in their lives?

It is interesting that in their apartment, there is only modern and post-modern artwork and architecture. I wonder how deeply this ties to Armand's trauma, since he himself was modeled (whitewashed as he was) in Late Renaissance/Mannerism artwork from the 1500s. How much of that experience drives his taste in art?

Bacon's juxtaposition and struggle with violence, power, and the dynamic of the perpetrator/victim is extremely interesting... the thoughts are still cooking about this one.

What do u guys think.... i've been microwaving this in my head all day along with the other painting!

Works Cited + Referenced:

[1] D. Farson, The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon, London, 1994, p. 134. [Taken from this JSTOR article, further cited below] [2] Referencing the catalogue here, which cites: Ziva Amishai-Maissels, Depiction and Interpretation: The Influence of the Holocaust on the Visual Arts, Oxford, New York, Seoul and Tokyo 1993, pp.189-90, 225-6, 354. [3] M[ichael] C[ompton], letter to Francis Bacon, 6 Jan. 1959, Tate Gallery cataloguing files. [4] Francis Bacon, letter to Tate Gallery, [9 Jan. 1959], Tate Gallery cataloguing files. [5] Arya, Rina. “The Primal Cry of Horror: The A-Theology of Francis Bacon.” Artibus et Historiae 32, no. 63 (2011): 275–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41479747.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post 1: Introduction

Hello, Readers,

My first experience with poetry--or at least the first I can remember--began when I was eleven years old. My mom still had her high school copy of Immortal Poems of the English Language, a poetry anthology edited by the poet Oscar Williams. She was a nurse who often worked long, difficult hours, but if she was in the right mood, she'd dig out her copy of Immortal Poems and read to my brothers and me. Her favorite were the British Romantic poets: Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, and Keats.

This experience I mentioned above remains one of my most vivid childhood memories. It was stormy night, and we had lost power. In the flickering candlelight, she read the entirety of Coleridge's "The Rime of The Ancient Mariner." Though I was too young to really appreciate or even understand what Coleridge was getting at, I remember being amazed at the sounds and rhythms of the poem, it's forlorn-sounding ballad meter, and the idea of a sinner condemned to wander the earth for all eternity to tell his tale to anyone who would listen.

Childhood moments like this one that laid the foundation for my love of poetry, however, I did not take to poetry until much later in life. Throughout high school, I cared more for prose--short stories and novels. I didn't "get" poetry, or really care for it. About halfway through my undergraduate education, I decided to take a survey course in British literature. When I looked at the reading list for this course, I was surprised to see that almost every assigned text was verse. I remember the course began with William Blake's "The Garden of Love" and ended with Seamus Heaney's "Digging." I almost dropped the course, but I decided to stick it out. This decision changed my life.

I quickly discovered that I loved poetry! I just had never had a great teacher of poetry, someone who is passionate about form, meter, and rhythm, and cared for the effects of grammar and syntax on the reader as much as he cared for the philosophy and historical contexts informing the poem. He also read poetry with real emotion, conviction, and passion--something I had not encountered since my mother read to me as a child.

I became obsessed with the works of Keats in this course, and suffice it to say that I was hooked. I changed my major from History to English at the end of the semester.

I took many more classes with this instructor, and each one of them was verse-centered. Out of the 7 or 8 courses I had with him, I can count on one hand the amount of prose that we read. Together, we covered all the major periods of British poetry, and by the time I graduated, I had built up a substantial base of knowledge about poetry.

Without my first teacher--my mother--and this second teacher many years later, I do not think I would be here with you all today. For many years, I worked blue-collar jobs and drifted aimlessly. Even when I decided to begin college (and for quite a while after), I had no clue about what I wanted to do. I am eternally grateful to my teachers for drawing this love of verse out of me and lighting my path.

Some of my favorite poets are John Donne, Percy Shelley, John Keats, Robert Browning, Matthew Arnold, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Emily Dickinson, W.B. Yeats, Thomas Hardy, T.S. Eliot, and Wallace Stevens.

I know very little about contemporary poetry, so I am excited to read these poets in this course. Maybe I will discover a few new favorites.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading. I look forward to our time together this semester.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once again the gap between politics and media, on one hand, and the general public, on the other, continues to be revealed in its scale. Survey after survey bring us the news that things are changing. That the British public is becoming more progressive in attitude towards refugees and asylum seekers, immigration, unions and industrial action, net zero targets and, most recently, British history.

The National Centre for Social Research’s British social attitudes survey shows a country that has become less nationalistic and jingoistic and, most sharply, less “proud” or “very proud” of British history. Along with that, there were also declines in pride in Britain’s democracy, its political influence and its economic achievements. The only two spheres where pride remained constant and high were sport, and art and literature.

Some of these changes are demographic, or the result of “generational replacement”, according to the survey. Younger generations’ idea of Britishness revolves around a “civic identity” rather than an ethnic one. And while 70% of people over 65 feel “it is important for someone to have been born in Britain”, only 41% of those under 35 feel the same.

There is an ethnic angle as well, with younger, more diverse generations being less likely to be tethered to historical notions of Britishness as a deposit of empire or ethnic heritage that needs to be preserved. And some of these changes can be attributed to the increasing connective tissue between people that has replaced shared uniform notions of national identity. Instead, there is an emergence of new shared references and experiences that create civic notions of belonging, relatability and kinship : the sort of art, literature and sport that score so highly on the pride barometer.

Reading surveys is like reading tea leaves – because we have results rather than reasoning – but it is difficult to imagine that, even after factoring in generational replacement, the raising of questions about empire, history, enslavement and the legacies of colonialism by an entire cohort of writers, academics, media organisations, cultural institutions and researchers has not played a part in many divesting from history as a source of national pride. They have had to face down not just backlash and condemnation from triggered members of the public, but from the media and the political sphere. The new Britain that is emerging is one that has come about organically and over time, but it is also one that has been dragged there.

In that process, the contest is framed by critics of reappraisal as one between those who want to see only the bad in British history and those who also want to recognise the good. In reality, the contest is between those who look for sources of identity in notions of supremacy, and those who do in markers of equality. In other words, overreliance on history, defensiveness about it and an insistence on seeing it as something that says something special about British character betray a lack of confidence, a fragility and a resistance to less hierarchical conceptions of identity. If we dispense with a definition of national character that has been expressed only in terms of exceptionalism in the past, then what replaces it?

Once that question is asked and treated as legitimate, all manner of risks are introduced. If we look to our current nation, one whose features are expressed so strongly in the survey, then one has to reckon with all sorts of uncomfortable realities that some want to deny. That postwar immigration and the diversity it has resulted in have changed the nation’s racial and political character irreversibly. That ethnicity alone is no longer a guarantee of status. And that our place in the world is undermined by overlapping economic crises and community fractures. Modern life, in short, is atomising and anxiety inducing. All the more so when subject to the sort of austerity that weakens public spaces and services, and creates an existence that one increasingly has to navigate rather than thrive in.

For the sort of pride that rests in our historical political and economic prowess, one has to search very hard in a present where reality for those other than a privileged few is increasingly about managing the rising cost of housing, transport, energy and food, and the state of the NHS and schooling, all while contending with Brexit-induced political instability, the recklessness and diminution of the political class and widening economic equality.

It’s not a mystery, then, why English rightwing politicians and the media focus so hectically on “woke” assaults on British heritage and history. It is why such panics about universities changing curriculums or the acute threat to memorials and statues are regular features on GB News and in rightwing newspapers. The right has desecrated the present and so must sanctify the symbols of the past, depositing in its performative protection all its fear of a new country where its influence, demographically and ideologically, is waning. And it’s not a mystery why Labour has broadly abdicated the job of channelling the transformation in public attitudes on race, immigration and history, choosing instead to focus on a “patriotism” that it neither defines nor promotes in any meaningful way. It has internalised that confected panic, and is still beholden to the view that Britain is conservative at heart and must be pandered to, not provoked. The result is declining pride in the country’s democracy and political accomplishments.

And the result is an absence of open contest over who we are: where a dangerous, destabilising minority – egged on by a right overrepresented in our public discourse and media – runs amok. The growing progressive majority, meanwhile, is advocated for, at great peril and cost, by those individuals and institutions outside the political sphere. And as referee is a government gone awol that intervenes only to crack down and mop up when violence spills out on to the streets.

What is being precipitated is not the much-feared confrontation with the forces of reaction, but the alienation of new progressives who do not recognise the country they live in as presented in their media and politics.

The holdouts are loud, powerful and well capitalised, and their assault is allowed to continue, despite all the signs that tell us their constituency is getting smaller and smaller in the rearview mirror – and that the country is leaving them behind.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

What would be the most underrated of the 'great books' (as in, great novels, philosophical texts, plays, etc. that made it into the Western canon?

I won't speak for the whole West, but as far as English-language literature goes, it must be The Faerie Queene. I'm sure people don't want to hear this because of the poem's length and archaism or even because its author was a would-be genocidaire, and I'm sure other people think this is a Red-Scareish received opinion from everybody's favorite Italian-American lesbian contrarian guru (with whose reading of the poem I disagree, by the way, since she sees it as primarily Classical, and I see it as primarily Gothic). But in my experience if you read The Faerie Queene the whole continuum of British and American poetry and prose romance really does fall into place, and you will begin to understand more about what Milton, Blake, Keats, Hawthorne, Yeats, and more are doing.

It's not that I hadn't read The Faerie Queene at all before I finally finished the whole thing a couple of years ago. Like many an English major, I'd been assigned to read most of Book I in an undergrad survey course. That's a tempting approach because Book I is a self-contained allegorical romance and therefore teaches well, and it's kind of like a fantasy novel. But the more visionary and influential parts come later and are discontinuous, the parts that almost leap from medievalism into Romanticism: the Bower of Bliss, the Garden of Adonis, the Britomart story, the Talus episodes, the Mutabilitie Cantos. A lot of it is tedious and unmemorable, of course—Virginia Woolf's quip that no one has ever read it to the end obtains—but the extraordinary parts are extraordinary. And if sociopolitical relevance is a criterion of value, the questions Spenser poses about sex, gender, and politics remain pressing and unsolved, much as we may dislike his answers.

For anyone who's curious but doesn't want to commit to the entire block-like 1000-page Penguin Classic, I recommend the Norton Critical Edition of Spenser's poetry, which contains the most essential 50% or so of the whole.

(The Italian epic-romances by Ariosto and Tasso that influenced Spenser are probably neglected too, especially in English; I confess I haven't read them.)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

KODAIKANAL TRIP

EXPLORE & INSPIRE

The earliest references to Kodaikanal and the Palani hills are found in Tamil Sangam literature.[3] Tamil composition Kuṟuntokai, the second book of the anthology Ettuthokai, mentions the mountainous geographic region (thinai) of Kurinji. The region is associated with Hindu god Murugan and is described as a forest with lakes, waterfalls and trees like teak, bamboo and sandalwood.[4] The name of the region, Kurinji, derives from the name of the famous flower Kurinji found only in the hills and the occupants of the region were tribal people whose prime occupations were hunting, honey harvesting and millet cultivation.[5][6] The hills were populated by the Palaiyar tribal people.[7]Coakers Walk in 1900

In 1821, a British Lieutenant, B. S. Ward, climbed up from his headquarters in the Kunnavan village to Kodaikanal to survey the area and reported of beautiful hills with a healthy climate with about 4,000 people living in well-structured villages.[8] In 1834, J.C Wroughten, then revenue collector of Madura and C. R. Cotton, a member of the Madras Presidency's board of revenue, climbed up the hills from Devadanapatti.[9] In 1836, botanist Robert Wight visited Kodaikanal and recorded his observations in the 1837 Madras Journal of Literature and Science.[10] In 1852, Major J. M. Partridge of the Bombay Army built a house and was the person to settle there.[9] In 1853, only six to seven houses were there when then Governor of Madras Presidency Charles Trevelyan visited in 1860.[11] In 1862, American missionary David Coit Scudder arrived.[9] In 1863, acting on a suggestion of Vere Levinge, then collector of Madurai, an artificial lake was formed.[11]

In 1867, Major J. M. Partridge imported Australian eucalyptus and wattle trees and in 1872, Lt. Coaker cut a path along the steep south east facing ridge which overlooks the plains below and prepared a descriptive map the region.[12][13] In the later half of the 19th century, it became a regular summer retreat for American missionaries and other European diplomats as a refuge from the high temperatures and tropical diseases of the plains.[14][15] In 1901, the first observations commenced at the Kodaikanal Observatory.[16] In 1909, the area had developed into a small town with 151 houses and a functioning post office, churches, clubs, schools and shops.[14] In 1914, the ghat road was completed.[11] It continued to served as a summer retreat during the British Raj and became a popular hill station later.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In February 2024, creature enthusiasts and popular media outlets celebrated what has been described as the 200-year anniversary of the formal naming of the "first" dinosaur, Megalosaurus.

There are political implications of Megalosaurus and the creature's presentation to the public.

In 1824, the creature was named (Megalosaurus bucklandii, for Buckland, whose work had also helped popularize knowledge of the "Ice Ages"). In 1842, the creature was used as a reference when Owen first formally coined the term "Dinosauria". And in 1854, models of Megalosaurus and Iguanodon were famously displayed in exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London. (The Crystal Palace was regarded as a sort of central focal point to celebrate the power of the Empire by displaying industrial technology and environmental and cultural "riches" acquired from the colonies. It was built to house the spectacle of the "Great Exhibition" in 1851, attended by millions.)

The fame of Megalosaurus and the popularization of dinosaurs coincided at a time when Europe was contemplating new revelations and understandings of geological "deep time" and the vast scale of the distant past, learning that both humans and the planet were much older than previously known, which influenced narrativizing and historicity. (Is time linear, progressing until the Empire is at this current pinnacle, implying justified dominance over other more "primitive" people? Will Britain fall like Rome? What are the limits of the Empire in the face of vast time scales and environmental forces?) The formal disciplines of geology, paleontology, anthropology, and other sciences were being professionalized and institutionalized at this time (as Britain cemented global power, surveyed and catalogued ecosystems for administration, and interacted with perceived "primitive" peoples of India, Africa, and Australia; the mutiny against British rule in India would happen in 1857). Simultaneously, media periodicals and printed texts were becoming widely available to popular audiences. For Victorian-era Britain, stories and press reflected this anxiety about extinction, the intimidating scale of time, interaction with people of the colonies, and encounters with "beasts" and "monsters" at both the spatial and temporal edges of Empire.

---

Some stuff:

"Shaping the beast: the nineteenth-century poetics of palaeontology" (Laurence Talairach-Vielmas in European Journal of English Studies, 2013).

Fairy Tales, Natural History and Victorian Culture (Laurence Talairach-Vielmas, 2014).

"Literary Megatheriums and Loose Baggy Monsters: Paleontology and the Victorian Novel" (Gowan Dawson in Victorian Studies, 2011).

Bursting the Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution (Martin J.S. Rudwick, 2010).

Assembling the Dinosaur: Fossil Hunters, Tycoons, and the Making of a Spectacle (Lukas Rieppel, 2019).

Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2020).

"Making Historicity: Paleontology and the Proximity of the Past in Germany, 1775-1825" (Patrick Anthony in Journal of the History of Ideas, 2021).

'"A Dim World, Where Monsters Dwell": The Spatial Time of the Sydenham Crystal Palace Dinosaur Park' (Nancy Rose Marshall in Victorian Studies, 2007).

Articulating Dinosaurs: A Political Anthropology (Brian Noble, 2016).

The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O'Connor, 2007).

"Victorian Saurians: The Linguistic Prehistory of the Modern Dinosaur" (O'Connor in Journal of Victorian Culture, 2012).

"Hyena-Hunting and Byron-Bashing in the Old North: William Buckland, Geological Verse and the Radical Threat" (O'Connor in Uncommon Contexts: Encounters between Science and Literature, 1800-1914, 2013).

And some excerpts:

---

When the Crystal Palace at Sydenham opened in 1854, the extinct animal models and geological strata exhibited in its park grounds offered Victorians access to a reconstructed past - modelled there for the first time - and drastically transformed how they understood and engaged with the history of the Earth. The geological section, developed by British naturalists and modelled after and with local resources was, like the rest of the Crystal Palace, governed by a historical perspective meant to communicate the glory of Victorian Britain. The guidebook authored by Richard Owen, Geology and Inhabitants of the Ancient World, illustrates how Victorian naturalists placed nature in the service of the nation - even if those elements of nature, like the Iguanodon or the Megalosaurus, lived and died long before such human categories were established. The geological section of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, which educated the public about the past while celebrating the scale and might of modernity, was a discursive site of exchange between past and present, but one that favoured the human present by intimating that deep time had been domesticated, corralled and commoditised by the nation’s naturalists.

Text by: Alison Laurence. "A discourse with deep time: the extinct animals of Crystal Palace Park as heritage artefacts". Science Museum Group Journal (Spring 2019). Published 1 May 2019. [All text from the article's abstract.]

---

[There was a] fundamental European 'time revolution' of the nineteenth century [...]. In the late 1850s and 1860s, Europeans are said to have experienced ‘the bottom falling out of history’, when geologists confirmed that humanity had existed for far, far longer than the approximately 6,000 years previously believed to represent the entire history [...]. ‘[S]ecular time’ became for many ‘just time, period’: the ‘empty time’ of Walter Benjamin. […] The European discovery of ‘deep time’ hastened this shift. [....] Historicism views the past as developments, trends, eras and epochs. [...] Victorians were intensely aware of ‘historical time’, experiencing themselves as inhabiting a new age of civilization. They were obsessed with history and its apparent power to explain the present […].

Text by: Laura Rademaker. “60,000 Years is not forever: ‘time revolutions’ and Indigenous pasts.” Postcolonial Studies. September 2021.

---

At the time when geology and paleontology emerged as new scientific disciplines, [...] [g]oing back to the 1802 exhibition of the first Mastodon exhibited in London’s Pall Mall, […] showmanship ruled geology and ensured its popularity and public appeal [...]. Throughout the Victorian period, [...] geology was as much - if not more - sensational than the popular romances and sensation novels of the time [...]. [T]he "rhetoric of spectacular display" (26) before the 1830s [was] developed by geological writers (James Parkinson, John Playfair, William Buckland, Gideon Mantell, Robert Blakewell), "borrowing techniques from [...] commercial exhibition" [...]. The discovery of Kirkdale Cave in December 1821 where fossils of [extinct] hyena bones were discovered along with other species (elephant, mouse, hippopotamus) led Buckland to posit that the exotic animals [...] had lived in England [...]. Thus, the year 1822 was significant as Buckland’s hyena den theory gave a glimpse of the world before the Flood. [...] [G]eology became a market in its own right, in particular with the explosion of cheaper forms of printed science [...] in cheap miscellanies and fictional miscellanies, with geological romances [...] [...] or [fantastical] tropes pervading [...], "leading to a considerable degree of conservatism in the imagery of the ancient earth" (196). By 1846 the geological romances were often reminiscent of the narrative strategies found in Arabian Nights [...].

Text by: Laurence Talairach-Vielmas. A book review published as: “Ralph O’Connor, The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802 - 1856.” Review published by journal Miranda. Online since July 2010.

---

Dinosaurs, then, are malleable beasts. [...] [T]he constant reshaping of these popular animals has also been driven by cultural and political trends. [...] One of Britain’s first palaeontologists, Richard Owen, coined the term “Dinosauria” in 1842. The Victorians were relatively familiar with reptile fossils [...] [b]ut Owen's coinage brought a group of the most mysterious discoveries under one umbrella. [...] When attempting to rise to the top of British science, it helped to have the media on your side. Owen’s friendship with both Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray led to fond name-dropping by both novelists. Dickens’s Bleak House famously begins by imagining a Megalosaurus, one of Owen’s original dinosaurs. Both novelists even compared their own writing process to Owen’s palaeontological techniques. In the scientific community, Owen’s dinosaur research was first [criticized] by his [...] rival, Gideon Mantell, a surgeon and the describer of the Iguanodon. [...] Naming dinosaurs was a powerful way of claiming ownership [...]. Owen [...] knew the power of the press [...]. [M]useum exhibits [often] [...] flattered white patrons [...] by placing them at the apex of modernity. [...] Owen would not have been surprised to learn that the reconstruction of dinosaur bones is still an act that is entangled in politics.

Text by: Richard Fallon. "Our image of dinosaurs was shaped by Victorian popularity contests". The Conversation. 31 January 2020.

#abolition#ecology#paleo#imperial dinosaurs#victorian and edwardian popular culture#opacity and fugitivity

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good morning! I hope you slept well and feel rested? Currently sitting at my desk, in my study, attired only in my blue towelling robe, enjoying my first cuppa of the day. Welcome to Too Much Information Tuesday.

None of the Beatles were able to read music.

Actirasty is sexual arousal caused by sunshine.

An estimated 40% of your happiness is genetic.

The truth is never as painful as discovering a lie.

The record for most female orgasms in one hour is 134.

Marijuana can aid in slowing down the growth of cancer cells.

In 1800, the average age of an American was 16, today it is 38.

The Wikipedia page for 'Pedant' has been edited over 500 times.

The average American adult hasn’t made a new friend in five years.

In 2007, eight-year-old twin boys from Ohio invented wedgie-proof underpants.

The United States has been involved in some conflict for about 93% of its existence.

Just five minutes of movement every hour can reverse the harmful effects of inactivity.

Male coin spiders only have sex once. After mating, they chew off their own genitals.

People who spend money on experiences rather than material items tend to be happier.

Sex burns about 3-5 calories a minute. (One-Minute Man ain’t burning many calories!)

Sitting for more than three hours a day can reduce a person's life expectancy by two years.

South Korea shut down its entire space programme in 2014 when its only astronaut resigned.

Jay-Z is now the wealthiest musical artist in the world, with a net worth of about $2.5 billion.

If you are 16 or older, there's an 80% chance you've already met the person you are going to marry.

Drinking tea, particularly green tea, can help lower blood pressure. (Green tea is my first cuppa of the day!)

Out of the nearly 200 countries in the world, only 22 of them have never experienced a British invasion.

From 1700 to 1905, cows were tied to posts in St James's park and their milk sold 'straight from the udder'.

In 1952, the great smog of London was so bad that blind people led sighted people home from the train station.

The average woman absorbs up to five pounds of damaging chemicals a year thanks to beauty products.

According to its website, WD40 was once used by police to remove a naked burglar from an air-conditioning vent.

An attempt to make the world's biggest sandwich in Iran failed when the crowd ate it before it could be measured.

Even if they oppose it morally, roughly 40% of Americans surveyed would still help a loved one seeking an abortion.

The average man will spend 10 years of his life working, three years going to the toilet and four years waiting in line.

Erotomania is a psychological disorder where the sufferer has delusions that another person is in love with him or her.

In Japan, you can get QR codes imprinted on headstones. You simply scan the code, then watch a video about that person’s life.

When the first sewing factories opened, seamstresses complained of 'extreme genital excitement' caused by the sewing machines.

In the US, marijuana was initially made illegal by a man who testified the drug made white women want to hook up with black men.

Yellow teeth are stronger, the natural colour of our teeth is a light yellow colour. Whitening your teeth can permanently weaken them.

British politician Alan Johnson was mocked in 2005 when he had the role of Productivity, Engineering, and Industry Secretary (PEnIS).

In the 1670's, the Pope bought ‘St. Peter's beard’ from highwayman Dick Dudley and kissed it, not knowing it was actually a prostitute's pubic wig.

Although only 836 people live in the French village of Montolieu, it has one bookshop for every 56 residents as well several workshops and museums dedicated to the craft of making books.

The first occupational disease ever recorded in medical literature was 'chimney sweep's scrotum', testicular cancer caused by chronic irritation of the testicular skin by soot and chimney tars.

After movie studios declined, ‘Monty Python and the Holy Grail’ was instead financed by Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Genesis, Jethro Tull, and Elton John, all of whom saw it as “a good tax write-off."

Hawaiian pizza was invented in Canada by a man from Greece. He was inspired to put a South American ingredient on an Italian dish after eating Chinese food. It then went on to become the most popular kind of pizza in Australia.

The Japanese marathon runner Shizo Kanakuri fell asleep while taking a break during the 1912 Olympic marathon in Stockholm. In 1967, the Swedes invited him to return and finish the race. His final time was 54 years, 8 months, 6 days, 5 hours, 32 minutes and 20.3 seconds.

Okay, that’s enough information for one day. Have a tremendous and tumultuous Tuesday! I love you all.

#mixcloud#mi soul#dj#music#new blog#lockdown#coronavirus#books#democracy#brexit#cronyism#election#tuesdaymotivation#radio

4 notes

·

View notes

Text