#story before Sote journey

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

[Item design] ✨🗡️

''Take my heart with you.''

→ item description

#story before Sote journey#elden ring fanart#radagon of the golden order#tarnished#oc: anna#elden ring#tarnished oc#shadow of the erdtree#elden ring comic#radanna#radagon the order#from the ashes#radagon#original item design#item design#design

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

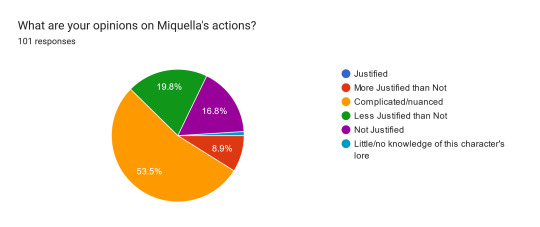

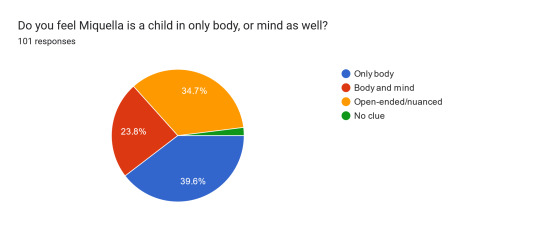

⚜️ SOTE Impressions Survey Results ⚜️

Earlier, I cycled around a survey to get opinions on the story of Elden Ring's DLC, and 101 respondents answered!! Following through with my promise, here are now all the results as recived.

Most all of these responders are likely from Tumblr, with potentially just a few from Twitter. To my knowledge this was never posted anywhere else, so these results can likely be best considered the thoughts of a good chunk in the Tumblr sphere of players!

I've done my best to make everything sufficiently readable, but there's still quite a bit in length here, apologies. The text on the actual charts may or may not be difficult to actually read, but I've given small summaries after each question to try and mitigate this.

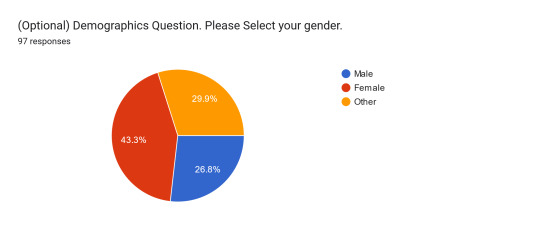

First, the basic demographic questions:

These two were optional, but almost entirely filled by all respondents nonetheless. It’s a pretty good split between gender! I half wish I’d made it more specific just for curiosity, but eh. Age range is primarily 19-25, with 26-30 second place.

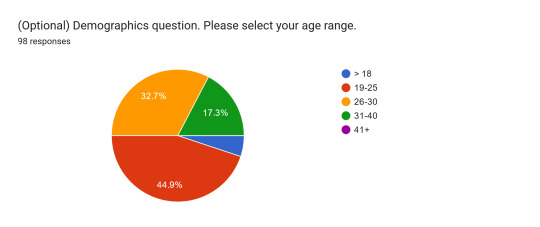

A question to determine how familiar players were with Fromsoft’s soulsborne genre and writing. Most respondents are indeed Fromsoft regulars.

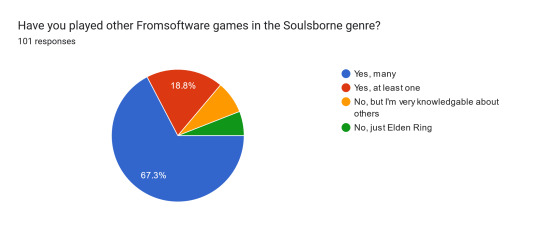

Most respondents fully expected Miquella to be Morally Grey before DLC release, with only a somewhat smaller amount expecting True Good over True Evil.

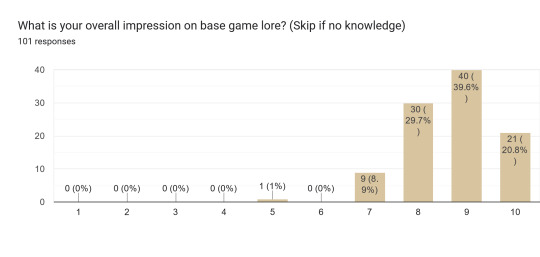

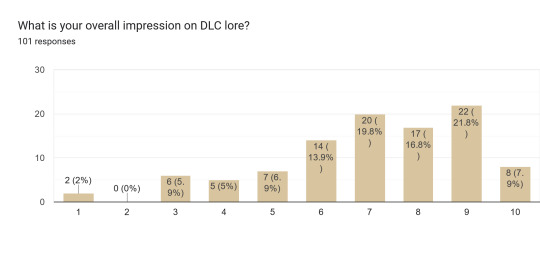

These speak for themselves. Base game lore has consistently high scores, whereas while DLC lore still has high peaks, there’s still much more of a spread haha.

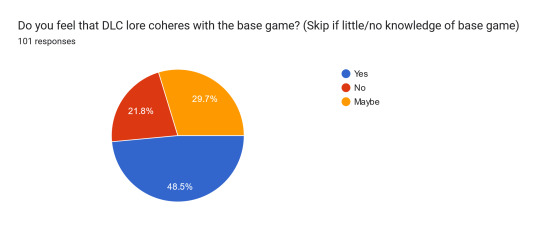

Despite it all there’s more people saying the DLC lore coheres with base game more than not??

Have you changed opinions on the DLC's lore at any time since it's release? If so, how?

No (no elaboration) - 18 No change, i feel negative- 15 No change, i feel positive- 10 Yes, I feel worse- 2 Yes, I feel better now- 18 Yes (no elaboration)- 6 N/A- 7

And wherever there’s nuance it’s usually a lot of “yeah I see the vision, but some execution could ultimately have been better.” In hindsight this is also a question I should’ve made multiple choice…

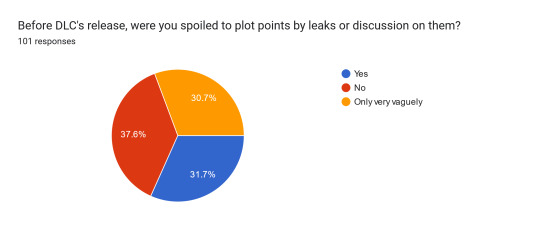

A very high chunk of people were spoiled to any degree beforehand!

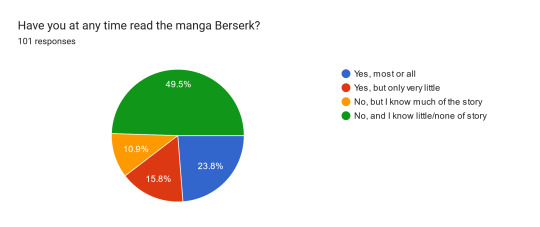

This question was due to all of the comparisons to Miquella as being similar to Griffith/initially expecting that of him before DLC. I think Berserk is a bit more popular in the Twitter/Reddit circles of fans, though.

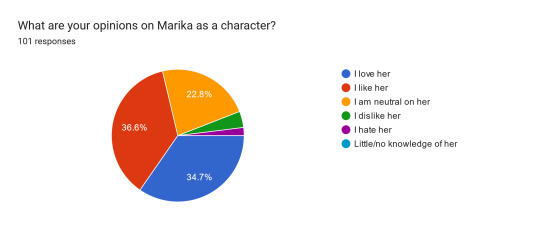

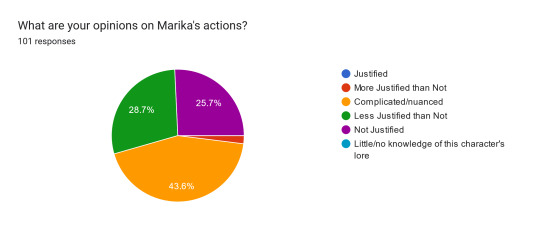

Primarily high impressions of Marika, with veeeryy low levels of believing she’s justified. Only a sliver of hate.

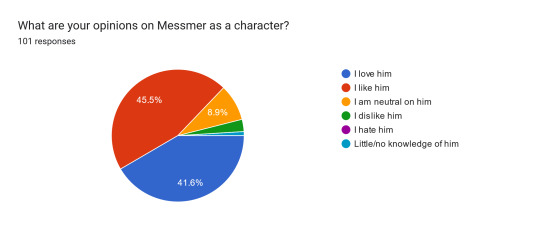

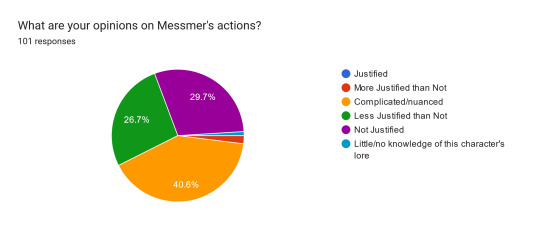

VERY high opinions of Messmer! Very small justifications of his actions, much in line with his mother.

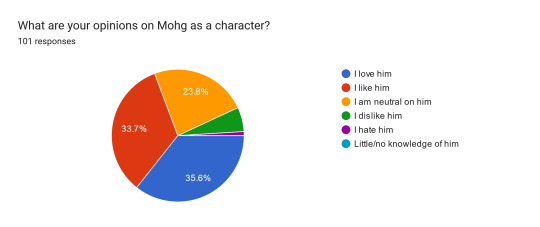

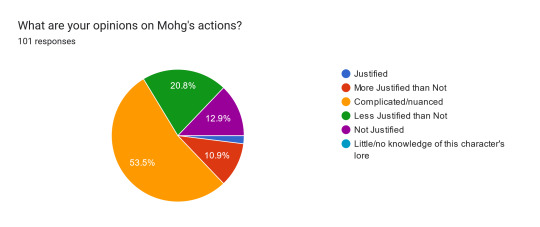

Very high impressions of Mohg overall, with a small slice of dislike, a tiny sliver of hate. People largely feel his actions are nuanced, with a small slice of more justified than not.

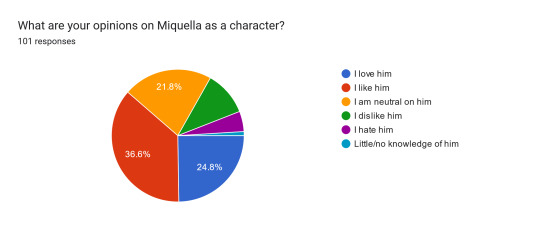

Miquella is by far the most divisive character! Albeit he still has some good chunks of Like and Love. Justification scores are much the same as Mohg, primarily complicated/nuanced.

More people feel Miquella is a child only in body, with a near-equal chunk feeling it’s open-ended/nuanced.

Surprisingly, most respondents do NOT believe in Mohg having sexual misconduct with Miquella… though perhaps some people felt this meant just with Mohg as a perpetrator, and not that there wasn’t iffy stuff at all? Nonetheless, this headcanon seems pretty prevalent in the community as a whole, but maybe that’s just due to all the loudest people with the crass jokes.

How do you feel about the writing choice of Radahn as Miquella's chosen king and consort?

Okay rather than try and take the stats for this one, I’m going to try and summarize the bulk of responses best as possible:

The least generous replies say this sucks ass. The most generous usually say “yeah, I see what they were going for, but the execution of this feels very flawed nonetheless.” One respondent states that the emphasis of Miquella’s plotline seemed to be on his choice of consort entirely, rather than his actual motivations or journey to get here.

Many people lament Malenia’s lack in things at all within DLC, past a single mention. A notable amount of people note that they would’ve been more accepting of the consort if it had ended up being Godwyn instead, because of the amount of weight he seemed to have in the base game lore alongside Miquella. At least one respondent laments the disservice “done to monsterfuckers everywhere” that we didn’t even get a physically monstrous boss in the end.

There’s a couple of people who go “oh yeah this makes sense for the both of them and/or I saw the signs along the way”, but they never go on to elaborate… the longest responses are always from people who are most unhappy, or are fairly understanding, but still ultimately unable to end up terribly pleased with this plot point.

Overall the reception to this plot point is decidedly poor, with the main grievances being how little foreshadowing or apparent basis there was, and how it changed the context of things in base game– such as Radahn’s first boss fight, the battle of Aeonia itself, Jerren’s wishes, and the sacrifices of all the soldiers between both armies. Even any concerns over implications of incest are honestly low priority here.

By far my personal favorite response is “I couldve written a better plot twist with three hoyrs of sleep and a coca col”, so shoutout to that one.

(Bonus) Optional because she's not relevant in the DLC. How do you feel about Ranni as a character and her actions?

I’ll be honest, this one was just because I think people’s thoughts on Ranni are a great judge of narrative comprehension. HAHAHA. But out of 91 responders to this one, most everyone cleared!

The bulk of responses are ultimately “yeah what she did to Godwyn was fucked up, but ultimately I understand it”. A few respondents note her narrative of female autonomy, and state their own reflection in this. Several note that she is selfish, but some aren’t particularly condescending with this and say that by all means, she’s just like the rest of the demigods if not still better than them.

A small handful also note that Ranni and Miquella are essentially foils to one another, where Miquella gives up everything for the sake of his Age of Compassion, but Ranni finds a means to keep her soul. It’s noted that even with his well-intentioned ambitions, he still ultimately fails as a reflection of Marika, whereas Ranni cuts herself from the cycle entirely.

A good handful of responses are little more than “hell yeah girlboss” and “fuck yeah that’s my wife” lol. On the other end, there’s a couple of responders who talk about how much they hate how she’s waifu’d, some disliking her purely because of this. Only about 2-3 responses in here are ones I’d truly consider character hate (without any seemingly justified reason) though.

Overall she’s more praised than not, with most everyone acknowledging her motivations, complexity, and role in the story. She’s often noted for her foils with Miquella, her goals of autonomy and the subsequent sympathy here from cis and trans female responders alike, with many acknowledgments that she is still by no means a saint.

And that's all! Thanks again to all of those who responded, and once more to those who've now read all the results. I still have the individual responses saved, so if I wanted I could go through and try to discern if there's any patterns related to how certain outcomes in opinion happen... but I'm tired!!! Hopefully if nothing else, this survey was a nice way to reflect and to sate some curiosity ✨

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

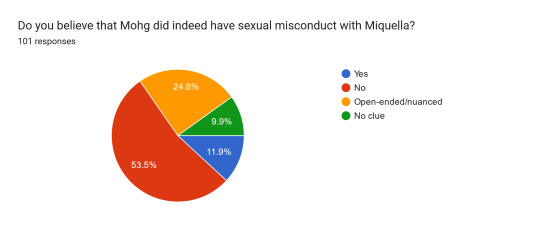

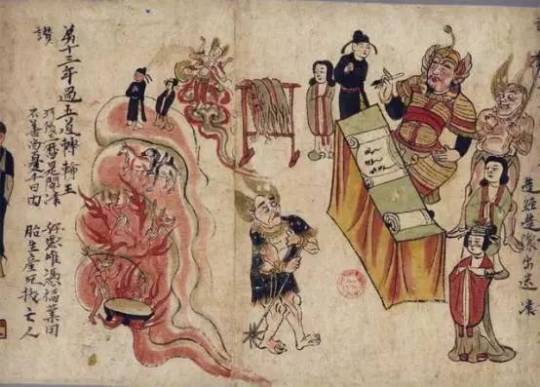

The Ten Kings of Hell: a history

The main judge of the dead in many schools of Buddhism, known as Enma Daiō in Japan and Yanluo Wang in China is a well known figure, in no small part thanks to numerous popculture adaptations. However, the exact history behind Yama, a Hindu deity, transforming into a Chinese bureaucrat, as well as the identities of Enma's subordinate kings of hell and lesser courtiers are relatively obscure. Under the cut I will discuss the development of the idea of ten kings of hell, the history of Enma himself (and why in theory you could say there's two of him), as well as a number of associated figures. Read on if you want to find out which mythical figure the historical Buddha was purportedly disappointed with, how popular imagination turned a completely mundane government official into Yanluo's human guise centuries after his death, and much more.

When Buddhism entered China, it absorbed certain elements of local afterlife beliefs. Most important of these was the cult of Mt. Tai, one of the five sacred mountains of Taoism. Its deity, Taishan Fujun (泰山府君), is first attested in sources from the 4th century, but archaeological evidence and earlier references indicate that the landmark was an important site of religious rituals since antiquity. Like many other deities, Taishan was depicted in the garb of a monarch or court official. His main role was keeping track of human lifespans and judging the dead, and supposedly an underworld realm where the deceased lived existed under his mountain. For this reason, early Buddhist translators and interpreters in China sometimes translated the name of Buddhist hell, Naraka, as Mt. Tai. This in turn lead to a partial conflation of the Buddhist judge of the dead, Yama (Yanluo; 閻魔), with Taishan, resulting in the well known depictions of the former in the garb of a Chinese official. At times Yanluo was also portrayed with one of Taishan's symbols, the big dipper constellation, while a few texts and mandalas tried to identify Taishan as Citragupta, a Hindu deity considered to be Yama's scribe and assistant. It seems they were sometimes contrasted, with Yanluo depicted as compassionate and Taishan as harsh. Full conflation of Yanluo and Taishan never occurred – instead, an elaborate system of beliefs developed around them, elevating both of them to the rank of king of hell, and adding multiple other officials presiding over specific parts of the journey to a new incarnation after death. The concept of there specifically being ten kings determining the fate of each departed soul first developed in China during the reign of the Tang dynasty, with the names known today likely becoming the standard between the 9th and 10th centuries. The Sutra Spoken by the Buddha on the Prophecy of King Yama to the Four Orders concerning the Seven [Rituals] to Be Practiced Prior to Rebirth in the Pure Land (仏説閻羅王授記四衆預修生七往生浄土経), also known simply as Scripture of the Ten Kings (十王經) was the most influential work when it came to establishing the list of the kings, as well as the imagery which became a mainstay of Buddhist hell paintings in China and beyond. As some early sources, such as Sutra on Questions of Hells (問地獄經), attempt to link the kings of hell to the story about the death of the legendary Buddhist king Bimbisāra and his army, at times going as far claiming that the king became Yama himself after death, it's possible that this grouping of deities first developed in part as an extension of the well documented phenomenon of placating potentially vengeful spirits of dead military commanders by deifying them. Worth noting that in a few cases such figures, imagined as deities presiding over epidemics (as well as capable of protecting from them) were described as Taishan's subordinates. The belief in Ten Kings was most likely first introduced to Japan by the Tendai monk Jōjin (成尋; lived 1011–1081), as his travel diaries state that he obtained a copy of Scripture of the Ten Kings during his long pilgrimage to China. Japanese Buddhists eventually developed their own literature on the matter of hells and their kings – the most important example is The Scripture Spoken by the Buddha on the Causes of Bodhisattva Jizō Giving Rise to the Thought of Enlightenment and the Ten Kings (仏説地蔵菩薩発心因縁十王経), also known simply as The Sutra on Jizō and the Ten Kings (地蔵十王経). The popularity of Enma and his fellow monarchs of the afterlife grew considerably in Japan from the XIIIth century onward, with some Buddhist temples establishing separate halls housing figures of them, called Enmadō (閻魔堂- Hall of Enma) or Jūōdō (十王堂 - Hall of Ten Kings). The Ten Kings, as listed in aforementioned texts, are: #1: King Qinguang, or Shinko (秦広王): his name is seemingly derived from the state of Qin. No distinct iconography. Appears prominently in a text purportedly written by Nichiren, The Praise of the Ten Kings (十王讚歎鈔). #2: King Chujiang, or Shoko (初江王), “king of the river.” His name indicates he was seen as the overseer of the river separating the lands of the dead and the living, known as Sanzu in Japan. No distinct iconography. #3: King Songdi, or Sotei (宋帝王): his name is derived from the Song state (the one in the Zhou era, not the dynasty conquered by Mongols). No distinct iconography. #4: King Wuguan, or Gokan (五官王), “king of the five offices,” evaluated the weight of individual sins. The “offices” were understood as spirits serving under him who judged specific categories of evil deeds (killing, theft, fornication, lying and substance abuse), but the term was also a poetic way to refer to eyes, ears, mouth, nose and hands. He was seemingly significant in early Chinese sources even before the idea of ten kings fully developed, such as the 5th century Sutra of Consecration (灌頂經) as Yanluo's second in command, but it doesn't seem he was derived from a separate preexisting deity. Sometimes portrayed holding scales. He has assistants known as “the douji or good and evil” (善惡童子). #5: King Yanluo, or Enma (閻魔王), the Buddhist version of Hindu deity Yama, as described above. Some Chinese sources stated that he was originally the first among the kings, but was demoted to the position of the fifth due to his sympathy for the sinners. In Japan, he's often portrayed with two assistants named Shimyo, who reads the judgments, and Shiroku, who acts as a recording clerk. In some Chinese sources, the soil deity Tudi Gong is described as a subordinate of Yanluo. Curiously, Scripture of Ten Kings states that Yanluo will be eventually reborn as a Buddha called Puxian (普賢). #6: King Biancheng, or Hensei (変成王), “king of transformations,” probably due to presiding over the specifics of assigning a path of reincarnation. No distinct iconography #7: King Taishan, or Taizan (泰山王), the guardian of lifespans. Maintains the registry of human deeds. As noted in Compendium Sutra of the Six Perfections (六度集経), Taishan can be bribed. #8: King Pingdeng, or Byodo (平等王), “the impartial” or “the king of equality,” might have originally been Yanluo's title, upgraded to the status of a separate deity. Notably appears in Manichean(!) texts, such as Manichaean Hymns of the Lower Section (摩尼教下部讚) No distinct iconography regardless. #9: King Dushi, or Toshi (都市王), “king of the capital,” likely derived from pre-Buddhist Chinese folk deities like Duguan Wang and Duyang Wang. No distinct iconography. #10: King Wudao Zhuanlun, or Godō Tenrin (五道転輪王), “king of the five paths of reincarnation” (the six realms minus Asuras – the matter of adding or removing new realms of rebirth frankly deserves a separate post at somepoint), an adaptation of an older, though nonetheless Buddhist in origin, Chinese deity. He presided over reincarnation itself after the judgements. Depicted in a suit of ornate Chinese armor. In Japan he and Taizan were sometimes depicted as Enma’s assistants, in addition to Shimyo and Shiroku – to my knowledge, this has no direct precedent in Chinese art. The following example is stored in the Hoshakuji temple:

The Ten Kings were commonly associated with the bodhisattva Jizō , said to be a guardian of souls in hell. This topic frankly deserves a separate post, so I will not discuss it in detail here. Worth noting that its final stage were largely humorous Japanese depictions of Enma and Jizō engaging in various pastimes, such as this one by Ashi Kyōdō:

As noted above, the tenth king was, like Taishan, a preexisting deity integrated into the network of hell kings, known as Wudao Dashen/Godo Daishin (五道大神), and in Japan additionally as Godo Shogun (五道将軍) – the Great God or General of the Five Paths. Unlike well-established Taishan, Wudao is a figure whose origins are convoluted and puzzled writers as early in the 6th century. Prominent Taoist, Tao Hongjing (陶宏景; lived 452–536), noted that he was unable to pinpoint his textual origin: “I do not know who the Great God of the Five Paths is”(all translations in this entry courtesy of Frederick Shih-Chung Chen, from his article The Great God of Five Paths in Early Medieval China). It would appear that Wudao was a Chinese addition to the tales about the life of the historical Buddha, with the earliest versions mentioning him possibly dating as early as to the 3rd century. In these early texts, his name was Benshi (賁識 or 奔識) – his later one was merely a descriptive title. He was also sometimes known as “the great god among ghostly gods”. Benshi was described as a god of great martial prowess, armed with a sword and a bow. However, in all versions of the story, he casts his weapons aside as soon as he sees the approaching Buddha, and informs him he's destined to follow the path of devas. In a manuscript known as Puyao jing (普曜經), an interesting exchange occurs between them : Seeing the Bodhisattva coming, he [Benshi] released the bow, threw the arrows away, and untied the sword. He then stepped back. Then he kowtowed at the feet of the Bodhisattva. He said to the Bodhisattva: “In the era of Brahmadeva, I received the decree of the Celestial King to guard the Five Paths, but I do not know how this system works. I am not clever and lack understanding. I hope that you can tell me the meaning of it.” The Bodhisattva said: “Although you govern the Five Paths, you do not know where these beings are going or where they have originated. (...)”

Presumably, the Buddha was not impressed with Benshi's less than stellar performance; nonetheless, in the following paragraphs he entrusts him with guiding the dead to the correct realms of rebirth.

Wudao was commonly mentioned in the so-called „funerary passports” (the term is not metaphorical) and on votive objects, usually as a guardian guiding the dead through the afterlife and making sure they fulfilled the religious requirements. A later medieval Taoist source, Code of Nüqing for [Controlling] Demons (女青鬼律), claims that Wudao resides under the northwest spur of Mt. Tai. He was often invoked in exorcisms alongside the popular demon queller Zhong Kui. I found no source which would state directly when Wudao was introduced to Japan, but it is evident that he was featured in a number of esoteric Buddhist mandalas before the concept of ten kings became a fixed feature of the religious landscape of Japan, alongside fellow afterlife deities Enma and Taishan. All 3 of them were first and foremost bringers of longevity and prosperity in this context.

Enma in the context of esoteric mandalas is best understood as initially almost a fully separate entity from the Enma presiding over the ten kings. He was usually called Enma-ten (閻魔天) in them, and his depictions were much closer to the original Hindu Yama than to the Chinese bureaucrat he became in more mainstream Buddhism. An attribute he was portrayed with in them, the staff with one or two human heads, was nonetheless eventually absorbed into the image of Enma as a king of hell in Japan. Additionally, some of the latter mandalas, like the one below, combined both versions of Enma. Onmyodo rites such as Taizan Fukun no Sai and Enma-ten Ku also often invoked Enma as both a king of hell and esoteric deity capable of changing human fate, though it seems Taizan and other associated deities such as Myoken, Matara-jin or Shinra Myojin eventually became the default option in them, with Enma-ten being largely overshadowed by Enma as a king of hell.

One final matter worth discussing here is that in a bizarre twist of fate, real deceased officials eventually came to be associated with the Ten Kings in both China and Japan, as a bizarre echo of their possible origin as deified slain generals. In Japan, the most notable example is that of the Heian era courtier, scholar and poet Ono no Takamura (小野篁; lived 802–852); according to legends already well established in the Kamakura period, he found a pathway to hell, and due to his great skill was able to secure the position of Enma's third assistant for himself. Later sources, such as the Chikurinji illustrated scroll (篁山竹林寺縁起絵巻) elevate him to the rank of a king of hell in his own right, specifically as a replacement of Sotei. Evidently third official in the court of Enma was misinterpreted as third king at some point.

In China, the Song dynasty judge Bao Zheng (包拯; lived 999-1062), renowned in popular imagination for his dedication, willingness to punish not only commoners, but even nobles, and opposition to bribery (he famously stated that any of his descendants who will commit such a crime cannot be buried in the family mausoleum) came to be seen as either the human guise of Yanluo, or a replacement for him. It's likely the association between these historical and religious figures goes back to Bao's life – purportedly while he served as an official in Kaifeng, it was commonly said that he and Yanluo are the only judges in existence impossible to bribe.

Judge Bao's example illustrates well why the kings of hell remained a popular subject in art for centuries: for the average person, justice was unlikely to be served while they're alive, but the belief that everyone is equal in death, and the entities in charge of determining the fate of the dead are truly just and impartial, must've provided much needed hope. Simultaneously, the rare examples of truly just individuals in position of power must've seemed like almost supernatural occurrences, leading to the deification of figures such as Bao Zheng in folk religion.

Further reading:

Embracing Death and the Afterlife: Sculptures of Enma and His Entourage at Rokuharamitsuji by Ye-gee Kwon

Baogong as King Yama in the Literature and Religious Worship of Late-Imperial China by Noga Ganany

Officials of the Afterworld. Ono no Takamura and the Ten Kings of Hell in the Chikurinji engi Illustrated Scrolls by Haruko Wakayabashi

The Inflatable, Collapsible Kingdom of Retribution. A Primer on Japanese Hell Imagery and Imagination by Carolina Hirasawa

In Search of the Origin of the Enumeration of Hell-kings in an Early Medieval Chinese Buddhist Scripture: Why did King Bimbisāra become Yama after his Disastrous Defeat in Battle in the Wen diyu jing 問地獄經 (‘Sūtra on Questions on Hells’)? by Frederick Shih-Chung Chen

The Great God of the Five Paths (Wudao Dashen 五道大神) in Early Medieval China by Frederick Shih-Chung Chen

Indic Influences on Chinese Mythology: King Yama and his Acolytes as Gods of Destiny by Bernard Faure

The Scripture on the Ten Kings And the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism by Stephen F. Teiser

David K. Jordan’s Jade Guidebook site

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sote

Iranian producer* Sote (AKA Ata Ebtekar) has become an important, internationalising force in the experimental electronic scene. His 2002 release ‘Electric Deaf’ – a frenetic slice of Drum’n’Bass – was released on Warp Records, since then he’s expanded his musical claws into more introspective works that also showcase a greater influence from his home country, most recently on Sacred Horror in Design (released via Opal Tapes). Not only is Sote producing intense, engaging music, he is also a co-founder of Tehran’s SET, a series of events exploring the avant garde.

Regularly bridging the gap between East and West, it was no surprise MusicMap.Global caught Sote perform at this year’s TodaysArt Festival in The Hague with a Dutch and Iranian band of collaborators. Journeying between the sublime and full-frontal sonic attacks, the show convinced us to reach out to Sote to discuss the Sacred Horror project, the role of improvisation in his work, and Tehran’s experimental electronic scene.

MusicMap.Global: Let’s first talk about your recent performance ‘Sacred Horror in Design’ at TodaysArt festival, which you performed alongside Arash Bolouri, Behrouz Pashaei and visual artist Tarik Barri. What was the concept behind the show, and how did this grouping form?

Sote: I had been thinking about doing another Persian influenced electronic music project a couple of years prior to Sacred Horror In Design. However, I was struggling with concepts and aesthetics not being proper and honorable from several angles. I didn’t want to exploit the whole hot Iran topic either. I definitely did not want to repeat myself with my experimentation of Iranian music and electronic music on previous albums such as Persian Electronic Music – Yesterday and Today, Dastgaah and Ornamental/Ornamentalism.

I had mentioned to Jan Rohlf (CTM director) that I had been working on an Iranian electro-acoustic audio/visual show (mostly in my head). When CTM Festival and Goethe Institute commissioned me to put it together I became focused and there was no escaping it anymore. Finally, I knew that I wanted to compose for an Iranian electro-acoustic performance with Iranian instrumentalist performing live (the key word being ‘performance’). Initially, I wasn’t thinking composing for an album, contrary to my previous work.

I started with a long list of Iranian musicians, at one point, working with a whole Iranian ensemble crossed my mind, but it really wouldn’t have been very practical due to deadline limitations… Ultimately, I chose Arash Bolouri and Behrouz Pashaei because they’re both very talented musicians and most importantly are very open to challenging musical and sonic trial and error scenarios outside of their comfort zone.

Tarik Barri was suggested to me by Jan Rohlf, whose work I was certainly aware of and always respected the fact that each one of his collaborations with other artists looked completely different from the other. Jan introduced my work to him, I met with him once at his Berlin home discussing ideas where I expressed what I wanted to do musically and sonically, and we clicked and decided to work together.

We continued our collaboration online via emails and file sharing. I composed and rehearsed with the two musicians in Tehran, sending excerpts to Tarik.

About 10 days before the CTM premiere, I went to Berlin to be under one roof with Tarik, where Arash and Behrouz joined us a week before the actual show, and we rehearsed together every day.

youtube

The inclusion of the santoor and setar in that performance added textures which aren’t prominent in your recorded work, is working with acoustic instrumentation something you’ve done before, and/or something you’ll return to?

My collaboration with Alireza Mashayekhi’s ‘Iranian Orchestra For New Music’ involved a whole orchestra worth of acoustic instruments (Iranian and Western). But you’re right, most of my work is usually all synthesis, this is where my passion lies. However, as long as I feel that I have something substantial to say through electro-acoustic methods then I will incorporate acoustic instrumentation within my compositions.

A friend of mine said that the recordings feel very process/improvisation based, but to me they feel quite structred, as did the live performance. Which one of us is ‘right’?

You’re both right actually. As I already stated, ’Sacred Horror In Design’ before all else was constructed for a performance. Overall, Iranian music is very much improvisation based. However, my personal interests in music alway are about structures at the very end. In other words, even in my most extreme experimentation phases, the final work, I have to compose.

A couple of the pieces started out as improvisations during the rehearsals, but eventually turned out to be a fixed idea.

Of course during the performances, I’d like to leave room for some improvising for the traditional musicians, and I obviously do some processing in reaction to the acoustic instruments. All in all, this dialog of the traditional instruments and electronics are of utmost importance.

Talk to us about the history of noise and experimentalism in Iranian musical culture. Who inspired you to become involved with electronic music, and who else in your vicinity is dealing with these sorts of sounds?

I have highest respect for Alireza Mashayekhi, who is a pioneer of avant garde music in Iran. However, my exposure to electronic music started during my childhood in Iran around the revolution era where I started being interested in strange electronic sounds of various recorded music on cassette tapes that I got my hands on. During my teenage years in Germany, this matured via my obsessive listening to Electronic Body Music of the early and mid ’80s and eventually my involvement started in high school making electronic music.

youtube

Some of my top favorite Iranian electronic music producers are Siavash Amini, 9T Antiope, Dipole, Temp-Illusion, Leila Arab, Umchunga, Idlefon, Tegh, Bescolor, Pouya Ehsaei, Porya Hatami, Sara Bigdeli Shamloo, Nima Aghiani, and Arash Akbari.

A film called Raving Iran gained quite a bit of attention recently, and garnered some special screenings. I haven’t seen the film, but the trailer seemed to frame the story as people essentially risking their lifestyles for their love of music. How recognisable is this scenario to you?

I haven’t seen the film either. Along with most of the above mentioned artists, we are actively performing and making music here in Iran and our lives are definitely not in danger.

You’ve lived in Iran, Germany, the U.S., and are now based in Tehran. Very broad question, but how has each of those moves shaped you, and changed/enhanced your perspective on your home country?

This could be a very long answer, but I think one of the most important outcomes is the fact that I have a deeper appreciation for the positive elements of my cultural heritage.

In previous interviews you’ve discussed organically expanding the experimental scene in Iran, bringing diverse audiences into the fray. How do you think the European events you’ve played recently compare with your events in Tehran, do you think the audiences there also need ‘expanding’?

In general, I find the audiences at our SET Experimental Art Events as well as other events in Iran more attentive than the Western part of the world. This does not mean that I find the European audiences or events to be problematic or in need of any major improvement.

I absolutely adore and admire how European governments support art and culture so vastly. If anything, the American government needs to pay more attention to art and culture instead of all the nonsense and hypocrisy they waste their time on.

Interview by Nicholas Burman

*Edited 19/10/2017. The article originally stated that Sote was “Iranian born”. While he is Iranian and spent a majority of his childhood in Iran he was actually born in Hamburg.

#9T Antiope#Alireza Mashayekhi#Arash Akbari#Arash Bolouri#avant garde#Behrouz Pashaei#Bescolor#CTM Festival#Dipole#Goethe Institute#Idlefon#Iran#Leila Arab#Nima Aghiani#Porya Hatami#Pouya Ehsaei#Sara Bigdeli Shamloo#SET Experimental Art Events#Siavash Amini#Sote#tarik barri#Tegh#Tehran#Temp-Illusion#TodaysArt Festival#Umchunga#Warp Records

0 notes