#sovietology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It is with a heavy heart that I have to announce my classmate who I've been doing homework with and generally employs a vaguely proletarian historiography in our discussions is an anarchist.

#its kind of a shame hes really bright i think he's just terminally poisoned by american sovietology#he did also say that he would near universally prefer the dictatorship of the proletariat over a country continuing under capital#probably the most respectful and well-intentioned “left wing bickering” session ive had

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

tagged by @oppenheimer-style

Last song I listened to:

youtube

let me live out my fantasies of being a depressed seaman in 1946 standing alone on a pier in sevastopol or odessa, staring out into the black sea on a cold winter night, with a full moon and smoking a fag, only my hands and head emerging out of my great full sized wool overcoat, battered by the freezing misty winds...

у чернооООГОО МОРЯЯЯЯЯЯ!!!

у чернооООГОО МОРЯЯЯЯЯЯ!!!

Books l'm currently reading:

I've just been window shopping through journals like Kritika and other Sovietology collections, reading a mish mash of different articles hoping to find something new after finishing Schattenberg's Brezhnev biography (which kicked ASS btw, across the board).

Currently watching:

brainrot of watching more House M.D. to understand properly the in-jokes of my buddies and also because I can't be bothered to slog through more of Fargo.

it's not lupus. it's never lupus. :-(

Movie watch list:

There are so many. You have no earthly idea. But a few:

I'm awful enough with watching shows, let alone managing to watch kino films. So I've been trying to cover what I can.

Not quite sure who to actually tag, as some of these questions were a bit out of my usual activities, but tagging @scrtchptch @strziga @kriegsherrin @towerjunkies @mauswife @henbane-heretic @ladabane and whoever else wants to move to the rhythm with it...!!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

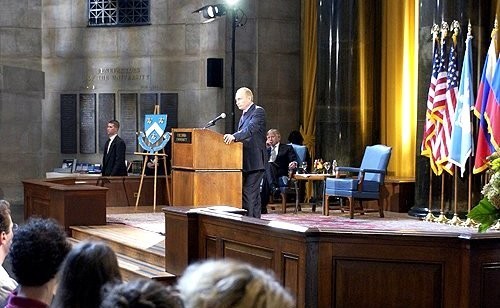

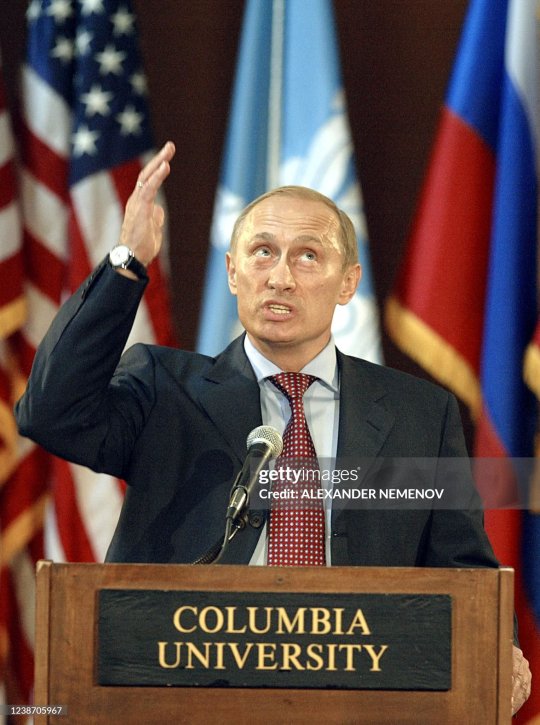

President Vladimir Putin visited Columbia University, where he answered questions from students and professors for an hour and a half on September 26, 2003, in New York.

The Russian leader urged those present to give up the concept of “Sovietology”. The inertia of old approaches is tenacious, the President said. The world has changed dramatically, the Soviet Union no longer exists, but still Sovietology survives.

That statement was not fortuitous: several centres at Columbia University study Russian history, politics, the Russian language and literature. About 500 students majoring in various subjects deal with Russian problems and many of them will shape Washington’s policy towards Moscow in the future.

After the speech President Putin answered a host of questions, about one-third of which were asked in Russian. The questions were about AIDS, the characteristics of the Russian language and even Vladimir Putin’s own speech, and various international problems.

After meeting with the students, Mr Putin took a short tour of the university. He looked at the Bakhmetyev Archive, one of the largest collections of Russian documents abroad. The President was given a copy of one of Leo Tolstoy’s letters. President Putin gave the archive a copy of a letter from Russian Foreign Minister Prince Gorchakov to the Russian envoy to the US regarding the Russian position on the American Civil War. The President also gave the archive a copy of Tsar Alexander I’s decree of 1808 appointing Andrei Dashkov (1775–1831) the first Russian Consul-General and charge d’affaires to the US.

President Putin also watched a baseball game between the Russian and American children’s teams.

#vladimir vladimirovich putin#vladdy daddy#new york#columbia state university#Президент России Владимир Путин

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decodificare la Russia: da Gorbaciov a Putin, com’è cambiata l’arte della cremlinologia

Sotto Breznev i cosiddetti sovietologi erano costretti a interpretare quello che accadeva dietro le quinte da una serie di segnali astrusi e di messaggi in codice, costruendo elaborate teorie. Gorbaciov aprì alla libertà di stampa. Con Putin è tornata la censura di sovietica… source

View On WordPress

#aggiornamenti da Italia e Mondo#Mmondo#Mmondo tutte le notizie#mmondo tutte le notizie sempre aggiornate#mondo tutte le notizie

0 notes

Text

How to cope with decease in science

How to cope with decease in science

Modern aspiring persons live in a dilemma. As opposed to ancient polymaths, we are working way too many hours to know everything. Plus, the aggregate body of knowledge is now colossal. If ‘everything’ is your goal, it is nowadays much harder to know ‘everything’. This is why many people choose the other extreme, which is knowing a very specific topic rather too well. This is a valid academic…

View On WordPress

#china#Energy#international affairs#International Relations#Natural Gas#russia#science#Sinology#social science#Sovietology

0 notes

Text

“Imagine a creature left behind by evolution. It is obedient, passive, and dependent on others for its care. Devoid of morals, it lies in order to survive. Such is the fate of Homo Sovieticus, the personality type identified by Yuri Levada’s sociological surveys on the ‘simple Soviet man’ of the late 80s. Homo Sovieticus was expected to go extinct with Russia’s post-Soviet transition, only to receive an alarming new lease of life. Scholars and journalists such as Masha Gessen and Joshua Yaffa have invoked the concept to attribute the country’s current brand of authoritarianism under Vladimir Putin to the subservient mindset of its citizens.

Gulnaz Sharafutdinova, a political scientist at King’s College London, rejects the ‘hopelessness’ and ‘Russophobia’ of such interpretations. She calls for ‘an emotionally intelligent’ approach that is focused on ‘empathizing with the Russian population, rather than pointing to where it went wrong’. In The Red Mirror, she attempts to diagnose the Russian condition without relying on Homo Sovieticus or assuming the superiority of its imagined foil, the liberal Western subject. She proposes that polling data like Levada’s can be stripped of its Cold War-era ideological foundations and retrofitted to produce a more convincing assessment of the collective psyche. ‘You can’t step twice into the same river—a classic saying’, she writes. ‘Or can you? . . . How can we use the insights in social psychology to arrive at a less biased understanding and give credit and the blame where they are due?’

Sharafutdinova grew up in the republic of Tatarstan, an oil-rich region with a majority Tatar population, and received her PhD from George Washington University. Her first book, Political Consequences of Crony Capitalism inside Russia (2010), examined the rise of corruption in the provinces. As privatization and free elections were introduced simultaneously in the early 90s, access to power meant access to property, and vice versa. Sharafutdinova identifies two political models that emerged: ‘centralized and noncompetitive’, the system favoured by the tight-knit Tatar elite, and ‘fragmented and competitive’, which characterized the Nizhnii Novgorod region under Yeltsin ally Boris Nemtsov. In the latter, politicians aired corruption scandals over the course of nasty campaigns, leading many voters to see elections as elite infighting and to respond with apathy and protest voting. As competitive democracy delegitimized itself, the Tatar model looked increasingly appealing. Popular disillusionment with democratic institutions united the self-interest of Putin’s circle with the desires of an alienated public. This, Sharafutdinova argues, is why most Russians didn’t mind when Putin abolished regional gubernatorial elections in 2004 (according to polls) and why his popularity remained high even as oil prices dropped.

By March 2014, when ‘little green men’ wearing unmarked uniforms appeared on the island of Crimea, apathy had given way to euphoria. The Red Mirror is focused on ‘high Putinism’—the enormous esteem the president enjoyed in the wake of the annexation, when his approval rating regularly exceeded 80 per cent. It fell to pre-Crimea levels of 65–70 per cent after the announcement of the highly unpopular pension reform in June 2018, which raised the retirement age by five years for men and eight for women, but has held relatively steady ever since. Like some liberal American writers who have made forays into Trump country, Sharafutdinova says that her study is motivated by a ‘personal urge’ to understand why many of her friends and family in Russia take a positive view of Putin. She does not accept that their perceptions stem from ‘brainwashing and propaganda’, ‘cultural preferences for a strong hand’, or ‘moral bankruptcy and the inability of Russian people to distinguish right from wrong’, as the Homo Sovieticus paradigm would suggest.

‘Homo Sovieticus’ inverted the Bolshevik concept of the New Man, which promised to reform human beings into a perfected, generalizable type. According to later observers, the revolutionary social experiment had gone horribly awry. Émigré sociologist Alexander Zinoviev created the first popular formulation of Homo Sovieticus in his novelistic depictions of Soviet life from the early 80s. Zinoviev’s interest in taxonomizing socialist man was expressed in a different key by Eastern Bloc dissidents who spoke out against what they saw as their peers’ passivity and conformity, captured by Vaclav Havel’s famous example of a greengrocer who puts a ‘Workers of the World, Unite!’ sign in his window. As Sharafutdinova explores here and in a 2019 article for Slavic Review (‘Was There a “Simple Soviet��� Person? Debating the Politics and Sociology of “Homo Sovieticus”’), these ideas dovetailed with the model of totalitarianism inspired by Hannah Arendt. Scholars of the totalitarian school, backed by generous funding from the US government, shared an assumption that the collective nature of state socialism destroyed the individual autonomy essential for democracy and free markets.

Levada put notions about the ‘simple Soviet man’ on an empirical foundation when he took over the All-Union Center for Public Opinion Research in the late 80s, as part of Gorbachev’s effort to enlist the social sciences in reforming the Soviet system. At the time, many members of the intelligentsia were decrying Russians’ degradation as a means of calling for change. Levada’s research combined concerns about the Soviet Union’s debased inhabitants (referred to in ironic domestic parlance as the ‘sovok’) with approaches derived from Talcott Parsons’ social systems theory. Levada discovered the cowering practitioner of doublethink that he had set out to find, while expressing confidence that this figure would die out along with the Soviet state.

While Western Sovietology faded away, criticism of the backward masses persisted among Russian intellectuals who sought a scapegoat for the country’s apparent failure to adapt to capitalist modernity. Levada’s successor Lev Gudkov, who has headed the independent Levada Center since 2006, announced that Soviet man was mutating and taking on increasingly cynical and aggressive forms. According to Gudkov’s Abortive Modernization (2011), ‘the main obstacle for Russia’s modernization “. . . is the type of the Soviet or post-Soviet man (homo sovieticus), his basic social distrust, his experience of adaptation to violence, that makes him incapable of receiving the more complex moral/ethical views and relationships, which, in turn, makes the institutionalization of new social forms of interaction impossible”. Gudkov’s argument became the go-to framing for Anglophone journalists in search of a hot (if reheated) take: ‘The Long Life of Homo Sovieticus’, a 2011 headline in The Economist proclaimed. Its usage intensified after Donald Trump’s election, when the increasingly ambiguous status of the liberal Western subject rekindled longings for its constituent other and the associated Cold War verities. The persistence of Soviet man is the central conceit of Gessen’s The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia (2017) and Yaffa’s Between Two Fires: Truth, Ambition and Compromise in Putin’s Russia (2020). Both authors are staff writers for The New Yorker.”

- JOY NEUMEYER, “BURYING HOMO SOVIETICUS.” New Left Review. Issue 129 May/June 2021.

#homo sovieticus#soviet union#sovietology#post-soviet#levada center#failure of sociology#cold war#putinism#russian federation#the russian character#national stereotypes

0 notes

Text

Grover Furr is nakedly & obviously ideological, but that fact does also raise the question of whether it's possible to research the history of Soviet Revisionism without being/becoming closely attached to a certain line of thought

#it doesnt help that so many takedowns of furr are so lackluster academic bad faith interactions#thinking esp abt kliman & radio free humanity 'taking down' it by restating standard western sovietology

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

meet soviet russia (1964 ed., cover design by al nagy)

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

💌!

I love your passion and your range of interests! From Sovietology to Roman Roy to DOGS!!!!!, you show how much you care and want to share that care and knowledge and I look forward to it. I end up learning quite a bit (or, if I may already know it or something about it, I get more context and information added to it) and I enjoy it. I also sympathize with the grad grind and drain and nevertheless she persisted!

<3<3<3

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

these leftcom orgs are doomed to failure, what a waste of time. my most common tag? probably ‘sovietology,’ why do you ask

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

What books on the Soviet Union, American foreign policy, or politics in general would you recommend for a beginner? What sites do you get your news from?

As for the last ask, specially books/authors that give a more accurate total for communism’s failures/successes than the Black Book.

I keep up with the news the way every God fearing American does nowadays: staring at my social media feed. I try and practice critical thinking about the sources I’m exposed to and why they might be reporting the way they are, with Ed Herman’s propaganda model and Carl Sagan’s baloney detection kit as guides.

With regards to Sovietology, I think you just have to take a wide breadth look at empirical research by academic historians. There’s a lot of debate between “revisionist” historians like Sheila Fitzpatrick and J. Arch Getty who go against what was the Cold War “non-revisionist” mainstream represented by the likes of Robert Conquest. The latter is your typical “Black Book” affair, and typically heavily politicized. For pure history, I like Michael Ellman, who takes the Soviet economy as his focus (although because he’s not trained as an economist he typically takes Western economists at their word as to the causes of problems of the Soviet planned economy - on the historical facts he’s typically dead on accurate despite this).

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

di NICOLA R. PORRO ♦

Yuval Noah Harari è un pensatore israeliano di frontiera. I suoi interessi si collocano in quel territorio di confine fra sociologia, filosofia e storia del pensiero scientifico dove spesso fiorisce la creatività dei pensatori autentici. Dopo il successo del suo Homo Sapiens. Da animali a dei (2014) ha pubblicato una nuova riflessione, altrettanto originale e provocatoria, dedicata a Homo Deus. Breve storia del futuro (2017). Un lavoro che descrive e celebra la laica divinizzazione dell’umanità, resa possibile dalla rivoluzione tecnologica. Nella quale, secondo Harari, siamo tanto esistenzialmente immersi da non percepire più quanto radicale e profonda sia la sua discontinuità rispetto al passato. Peccato però che la profezia abbia scelto a esempio un caso destinato ad apparirci presto sinistramente paradossale. Sostiene infatti lo studioso israeliano che dalla seconda metà del XX secolo l’umanità avrebbe definitivamente acquisito la capacità di prevenire o domare le tre storiche maledizioni della vita sociale: carestie, pestilenze e guerre. Dati alla mano, parrebbe più probabile morire di congestione dopo un’abbuffata da McDonald’s piuttosto che rimanere vittime di eventi al di fuori del nostro controllo. La siccità, il virus Ebola o un attacco di al-Qaeda, per fare qualche esempio…

Certo: l’epidemia del coronavirus non sembra destinata a produrre le catastrofi del passato. La peste nera del XIV secolo sembra abbia causato fra i settantacinque e i duecento milioni di vittime. A partire dal XV secolo Il vaiolo e le altre malattie esportate nelle Americhe dai conquistatori europei provocarono non meno di venti milioni di decessi nel solo Messico. Fra il secondo e il terzo decennio del Novecento l’influenza spagnola avrebbe ucciso fra i cinquanta e i cento milioni di persone. Sessanta anni più tardi l’Aids ne avrebbe sterminate almeno trenta milioni.

Più di recente, nel 2014, il virus Ebola ha invece causato “appena” undicimila vittime e anche il più letale Covid-19 non produrrà gli effetti apocalittici delle peggiori epidemie del passato. A vedere il bicchiere mezzo pieno, insomma, possiamo riconoscere ad Harari le attenuanti generiche. In assenza di una controprova inoppugnabile, siamo autorizzati a ritenere che i progressi della ricerca e l’adozione di misure di contrasto ispirate a princìpi scientifici ci avrà risparmiato alla fine qualche milione di vittime. Occorre però riflettere su altri aspetti cruciali. Come dimenticare, ad esempio, che nel nostro Paese, uno di quelli colpiti prima e più aggressivamente dall’epidemia, sino a metà febbraio fosse ampiamente diffusa la convinzione che l’Italia se la sarebbe cavata senza troppi danni? Abbiamo celebrato come niente fosse carnevali, eventi sportivi a porte aperte, cerimonie religiose e manifestazioni pubbliche. E altrove è andata anche peggio. La festa dell’8 marzo in Spagna sembra abbia rappresentato la miccia del dramma consumatosi a scala di massa poche settimane dopo. Negli Usa e in Gran Bretagna, dove le misure di distanziamento sociale e di contenimento sono state introdotte con colpevole ritardo, l’epidemia è esplosa a scoppio ritardato ma altrettanto drammaticamente.

Da dove ha dunque origine il disincanto verso le magnifiche sorti e progressive vagheggiate da Harari? È la non onniscienza della scienza che falsifica la sua teoria? O sono l’eredità del pensiero mitomagico, l’opportunismo della politica e il fatalismo scaramantico dell’inconscio collettivo a comprometterne l’efficacia? Insomma: con chi dobbiamo prendercela se l’homo sapiens non riesce a trasformarsi nell’homo deus?

La dimensione sociologica del problema, almeno quella, è tuttavia chiara. Essa riposa nella rappresentazione culturale della pandemia che noi stessi stiamo elaborando. Diffusa è la convinzione di vivere un evento epocale, inedito e forse irripetibile. Una percezione facilmente smentita dalla memoria storica della modernità. La sola autentica novità è rappresentata proprio dal vigore e dall’estensione assunte da questi inganni cognitivi, se è vero che una valente filosofa spagnola, Ana Carrasco Conde, si è spinta a prevedere che la tarda modernità produrrà una periodizzazione divisa fra un prima e un dopo la pandemia, così come tanti secoli fa si era convenuto di dividere il tempo lineare fra un prima e un dopo la venuta di Cristo. La questione, tuttavia, potrebbe non costituire soltanto una concessione all’ideologia autoreferenziale dell’eterno presente. La pandemia presenta infatti davvero caratteristiche che la differenziano da altri eventi di vasta portata. Non ha la brevità istantanea della catastrofe circoscritta nel tempo e nello spazio – un’esplosione nucleare, un terremoto -, che demarca con precisione un prima e un dopo in assenza di un mentre. Nemmeno però conosce la progressività temporale delle guerre tradizionali, eventi di lunga durata capaci di alimentare la speranza o l’illusione che l’azione umana che li ha generati possa prima o poi porvi fine attraverso la vittoria di una parte o una pace negoziata. Non per nulla, come testimoniano i grandi narratori del tempo, il carattere epocale delle guerre del Novecento verrà percepito solo a notevole distanza di tempo dalla fine dei conflitti. Per di più noi viviamo immersi in un sistema della comunicazione digitale che ci induce (o ci condanna?) a vivere l’offensiva del nemico invisibile in una sorta di temporalità ansiogena che mescola algide sequenze statistiche e fantasiose produzioni narrative. Al di là delle somiglianze apparenti la differenza esistenziale con l’esperienza vissuta dai nostri antenati recenti, si pensi alla spagnola, è abissale.

Senza infierire sulla profezia di Harari e tributando il dovuto omaggio a Francesco Guccini, si fa così strada l’dea che “un dio sia morto”. Non il Dio con la d maiuscola, quello trascendente della fede e della metafisica. No: il dio con la d minuscola, quello dell’ideologia del quotidiano. L’onnipotente divinità della tecnica, il sovrano dell’informazione, il signore della scienza applicata: un dio immanente, interamente umano. Una divinità della menzogna che ci aveva convertito alla religione del falso. Nel primo giorno del primo anno del dopovirus l’indicibile è rivelato. La tecnologia non può dominare la natura se non imparando a obbedirle: ce lo aveva insegnato il vecchio Bacone quattro secoli fa. La scienza, sconfinatamente più potente di quanto non sia mai stata nella storia umana, può sempre più spesso vincere le malattie. Ma non può eliminarle. L’illusione scientista dell’immortalità si è infranta.

Siamo dunque in presenza di un paradosso. Per un verso la conoscenza scientifica si erge come estremo baluardo di salvezza: dove si sono nascosti i nostri no-vax? Abbiamo almeno la speranza di esserci liberati delle idiozie no-qualcosa, linfa irrazionalistica per i populismi del Duemila?

Contemporaneamente, però, il covid-19 ha drammaticamente sconfessato anche la narrazione simmetrica e speculare. Dove sono andati a finire la visione trans-umanista, quel surrogato di vita eterna promesso dall’intelligenza artificiale, la secolare divinizzazione del futuro annunciata dalla rivoluzione digitale?

Siamo precipitati nella voragine con leggerezza, come sonnambuli condannati a replicare per l’ennesima volta un antico copione. Ha ricordato a titolo di esempio Zygmunt Bauman come il 9 novembre del 1989, mentre una dichiarazione equivocata di Günter Schabowski provocava la caduta del Muro di Berlino, fosse in corso un solenne congresso di sovietologi impegnati da giorni in dotte dissertazioni e minuziose analisi delle relazioni Est-Ovest. Mentre i politologi si preparavano a redigere le conclusioni del dibattito crollava in poche ore il Muro che aveva diviso l’Europa, il mondo, la rappresentazione stessa della storia contemporanea. La polvere sollevata dalle macerie avvolgeva il crepuscolo repentino di quello che avremmo ribattezzato il secolo breve.

Allo stesso modo trenta anni dopo nessuno dei potenti algoritmi che presiedono alla nostra aspettativa di futuro ha saputo presagire la sfida della pandemia all’umanità.

Tutti guardavamo da un’altra parte mentre la mostruosa potenza degli algoritmi era impegnata a orientare la scelta del film che avremmo acquistato on demand, il thriller che avremmo scaricato sul nostro e-book, il modello di tosaerba che Amazon ci avrebbe recapitato in capo a poche ore. Infallibili nel catturare e orientare i nostri desideri, nel trasformarli in bisogni da soddisfare dentro il circuito claustrofobico dell’universo digitale, gli algoritmi non avevano avvertito il minimo sentore della più grande crisi globale dell’ultimo secolo. La dovuta deferenza al pensiero del dottor Pangloss aveva tempestivamente cancellato dai radar i pochi ma ben documentati “predicatori di sventura” che già da tre mesi andavano disperatamente urlando al vento la tempesta in arrivo.

La questione non risiede allora nello strumento, nella tecnologia, nell’antica mai risolta contraddizione fra physis e techne. Il problema riguarda non gli strumenti del sapere e la loro efficacia. Concerne la finalità, non la potenza della conoscenza, rivelandoci quanto selettivo sia l’ordine che presiede all’universo digitale. Ci illudiamo di conoscere i meandri del nuovo sistema-mondo ma ne ignoriamo le evidenze. La più palmare e stridente delle quali è che i pochi sono diventati più ricchi mentre non è granché migliorata la vita degli altri. Non amo le formule mutuate dalle vecchie ideologie. Però come negare che l’anima dell’innovazione sia stata un’anima mercantilista? Quali eufemismi escogiteremo per non chiamare col suo nome, neo-liberismo, la filosofia sociale che si è eretta a ideologia della Grande Trasformazione?

La tecnologia forse ha soltanto offerto lo spartito per il canto delle sirene mentre ovunque i governi riducevano gli investimenti in quei comparti della ricerca scientifica meno remunerativi a fini di profitto ma di maggiore utilità collettiva.

La ricerca scientifica, d’altronde, ha per missione quella di trasformare il denaro in conoscenza, mentre la tecnologia ha quella di trasformare la conoscenza in denaro. Il capitalismo digitale ha privilegiato la seconda ai danni della prima, come dimostrano con spietata eloquenza la radiografia sociale della pandemia e alcuni casi esemplari – anche italiani – su cui sarà doveroso tornare e interrogarsi.

Forse abbiamo semplicemente bisogno di modificare la priorità: non la mortale immortalità dell’Homo deus bensì la fragile dignità dei mortali. Il rovesciamento della prospettiva, per paradosso, può allora restituire significato etico-politico alla profezia di Harari da cui abbiamo preso le mosse. A condizione che il “progresso” non assecondi la vocazione autodistruttiva che si è insinuata negli anfratti della Grande Trasformazione. Perché il genere umano può adesso davvero rendere inconsapevolmente superflua l’umanità stessa abusando dei propri “divini” poteri.

Il XXI secolo non ci ha liberato dalle epidemie, non ha edificato il nuovo Eden, non ha trasformato l’«Homo sapiens» nell’«Homo Deus». Soprattutto, non sembra capace di regalarci l’immortalità e la felicità eterna. Le grandi promesse della robotica, dell’intelligenza artificiale e dell’ingegneria genetica non saranno mantenute. Ma intanto hanno preso corpo sogni mai sognati e incubi mai vissuti. Il contagio ci precipita metaforicamente nell’inferno della biopolitica: carcerieri e prigionieri dei nostro corpi, agitati da paure ancestrali, incapaci di governare l’incertezza oltre le soglie di un lockdown.

È dunque un’illusione autoreferenziale, generata dall’inesorabile perdita della prospettiva storica prodotta dalla digitalizzazione dei saperi e stoltamente presentistica, quella di pensare a un passaggio d’epoca paragonabile alla cronologia storica pre-postcristiana. Certamente però dobbiamo dare risposte non rinviabili a interrogativi rimasti in sospeso . Dobbiamo cercarle in un universo di valori, interessi e identità – quello che sinotticamente, da Aristotele in poi, definiamo politica – che ci appare come un groviglio stretto in una tenaglia micidiale. Da una parte l’egemonia ideologica del liberismo in versione tecnocapitalista. Dall’altra, la sfida mortale dei nuovi populismi. Responsabili e vittime della crisi, tecnocapitalismo e nuovi populismi possono sopravvivere allo choc della pandemia solo imponendo un habitat culturale e sociale basato su una qualche sinergia fra i due modelli. Con il rischio di generare esiti autoritari e forme di crescente controllo sociale. La battaglia andrà perciò condotta innanzi tutto sul terreno della cultura, sulla costruzione di una nuova egemonia. L’ etica del sospetto, le farneticazioni antiscientiste, come la speculare demagogia sovranista, possono saldarsi con le logiche del tecnocapitalismo in un inedito patto scellerato. Capace di affermare ideologie regressive e di tracciare l’ordine politico del Medio Evo digitale.

La sfida è aperta a tutti gli esiti e non possiamo illuderci che “dopo” tutto sarà chiarito per sempre. La storia ci consegna esempi di grandi e felici innovazioni maturate come risposta collettiva alle crisi. Ma anche casi di declino irreversibile e di involuzione politica. Insomma: avremo ancora bisogno, come fu fra le due guerre del Novecento, di attingere al pessimismo della ragione perché prevalga l’ottimismo della volontà.

NICOLA R. PORRO

Nel tempo del virus. Incubi, sogni e profezie di NICOLA R. PORRO ♦ Yuval Noah Harari è un pensatore israeliano di frontiera. I suoi interessi si collocano in quel territorio di confine fra sociologia, filosofia e storia del pensiero scientifico dove spesso fiorisce la creatività dei pensatori autentici.

0 notes

Note

Spinx

𝐒𝐩𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐱 - What was the last book you read?

I’ve been abusing the poor librarians at my university thanks to the inter-library loan system, letting me get my hands on things I normally can’t.

This is a pretty nice text. It’s a compilation of a bunch of different articles / papers about different aspects of the Brezhnev period. For example, one chapter is about Brezhnev’s deft skill in the political intrigue needed to oust Khrushchev, showing that he was anything but an “easily controllable puppet” pushed on by other politburo members.

Another chapter explores how the “national question” was effectively a non-issue during the Brezhnev period, as minority nationalities in the USSR enjoyed far greater rights than they ever had before. The percentage of ethnic Russians was declining in almost every territory except Belarus and Ukraine, and in every single SSSR and besides the two latter, the local language and identity was generally preferred. Nationalist voices were kept on the fringe and were mostly a non-issue, as the titular nationalities of SSRs and ASSRs enjoyed a much greater level of autonomy and right to protect their culture that people never give Brezhnev credit for. The undoing of the “national question” was entirely a Gorbachevite creation.

There are other chapters, going over the details of his foreign policy, how domestic consumer industry progressed, the healthier state of academia under him (the Brezhnev period being a golden era, looked upon with nostalgia even today, with the criminal under funding and neglect of academia, etc.

I thought it was pretty refreshing as it came about only 11 years after the fall of the USSR in 2002, which is impressive as only today - thirty years after the collapse - is it finally becoming acceptable to host an academic discussion and analysis of the Soviet Union without accusations of communist sympathies. Sovietology is still a field that’s in it’s infancy, and gets relentlessly attacked (and no doubt will be only more now with recent events), but it surprised me to see a text like this come out so early.

There are some newer texts on Brezhnev from 2016 and 2019 that I want to check out, so I’ll see how those compare.

Thanks for the ask anon!

5 notes

·

View notes