#source: stacy schiff ‘the witches’ on the 1692 salem witchcraft trials

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

acknowledging that the history is horrible and all, i still think that one of the most whack ass things i’ve ever read about europe was the following:

1. in britain, people convicted of witchcraft mostly were hanged

2. in france, people convicted of witchcraft mostly were burned at the stake

HOWEVER: in the channel islands, geographically & culturally right between britain & france, people weren’t sure which nation’s witch murder method to use, so they would hang people and then burn them, just to reeeeally cover their bases

#source: stacy schiff ‘the witches’ on the 1692 salem witchcraft trials#don’t have the exact page on me but its bookmarked hmu if u want it#witchcraft#history

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A History of Witches: a non-fiction list

The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present by Ronald Hutton

Why have societies all across the world feared witchcraft? This book delves deeply into its context, beliefs, and origins in Europe’s history.

The witch came to prominence—and often a painful death—in early modern Europe, yet her origins are much more geographically diverse and historically deep. In this landmark book, Ronald Hutton traces witchcraft from the ancient world to the early-modern stake. This book sets the notorious European witch trials in the widest and deepest possible perspective and traces the major historiographical developments of witchcraft. Hutton, a renowned expert on ancient, medieval, and modern paganism and witchcraft beliefs, combines Anglo-American and continental scholarly approaches to examine attitudes on witchcraft and the treatment of suspected witches across the world, including in Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, Australia, and North and South America, and from ancient pagan times to current interpretations. His fresh anthropological and ethnographical approach focuses on cultural inheritance and change while considering shamanism, folk religion, the range of witch trials, and how the fear of witchcraft might be eradicated.

Witchcraft: A Secret History��by Michael Streeter

Witchcraft: A Secret History unravels the myth from the mystery, the facts from the legends. Meet all the witches of your imagination and discover the meanings of their rituals and rites, their lore, and their craft. Discover the significance of their sabbats and covens, their chalices and wands, their robes and their religion. Unlock the secrets of the legendary witches of mythology and folk tales and find out how these early stories influenced the persecutions and witch-hunts of the Middle Ages. Learn about the people who inspired the pagan revival and how their work in literature and magic rekindled the fires of the sabbats across Europe and the New World today.

A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience by Emerson W. Baker

Beginning in January 1692, Salem Village in colonial Massachusetts witnessed the largest and most lethal outbreak of witchcraft in early America. Villagers—mainly young women—suffered from unseen torments that caused them to writhe, shriek, and contort their bodies, complaining of pins stuck into their flesh and of being haunted by specters. Believing that they suffered from assaults by an invisible spirit, the community began a hunt to track down those responsible for the demonic work. The resulting Salem Witch Trials, culminating in the execution of 19 villagers, persists as one of the most mysterious and fascinating events in American history. Historians have speculated on a web of possible causes for the witchcraft that started in Salem and spread across the region—religious crisis, ergot poisoning, an encephalitis outbreak, frontier war hysteria—but most agree that there was no single factor. Rather, as Emerson Baker illustrates in this seminal new work, Salem was "a perfect storm": a unique convergence of conditions and events that produced something extraordinary throughout New England in 1692 and the following years, and which has haunted us ever since. Baker shows how a range of factors in the Bay colony in the 1690s, including a new charter and government, a lethal frontier war, and religious and political conflicts, set the stage for the dramatic events in Salem. Engaging a range of perspectives, he looks at the key players in the outbreak—the accused witches and the people they allegedly bewitched, as well as the judges and government officials who prosecuted them—and wrestles with questions about why the Salem tragedy unfolded as it did, and why it has become an enduring legacy.

Royal Witches: Witchcraft and the Nobility in Fifteenth-Century England by Gemma Hollman

Until the mass hysteria of the seventeenth century, accusations of witchcraft in England were rare. However, four royal women, related in family and in court ties—Joan of Navarre, Eleanor Cobham, Jacquetta of Luxembourg and Elizabeth Woodville—were accused of practicing witchcraft in order to kill or influence the king. Some of these women may have turned to the “dark arts” in order to divine the future or obtain healing potions, but the purpose of the accusations was purely political. Despite their status, these women were vulnerable because of their gender, as the men around them moved them like pawns for political gains. In Royal Witches, Gemma Hollman explores the lives and the cases of these so-called witches, placing them in the historical context of fifteenth-century England, a setting rife with political upheaval and war. In a time when the line between science and magic was blurred, these trials offer a tantalizing insight into how malicious magic would be used and would later cause such mass hysteria in centuries to come.

The Witches: Salem, 1692 by Stacy Schiff

The panic began early in 1692, over an exceptionally raw Massachusetts winter, when a minister's niece began to writhe and roar. It spread quickly, confounding the most educated men and prominent politicians in the colony. Neighbors accused neighbors, husbands accused wives, parents and children one another. It ended less than a year later, but not before nineteen men and women had been hanged and an elderly man crushed to death. Speaking loudly and emphatically, adolescent girls stood at the center of the crisis. Along with suffrage and Prohibition, the Salem witch trials represent one of the few moments when women played the central role in American history. Drawing masterfully on the archives, Stacy Schiff introduces us to the strains on a Puritan adolescent's life and to the authorities whose delicate agendas were at risk. She illuminates the demands of a rigorous faith, the vulnerability of settlements adrift from the mother country, perched--at a politically tumultuous time--on the edge of what a visitor termed a "remote, rocky, barren, bushy, wild-woody wilderness." With devastating clarity, the textures and tension of colonial life emerge; hidden patterns subtly, startlingly detach themselves from the darkness. Schiff brings early American anxieties to the fore to align them brilliantly with our own. In an era of religious provocations, crowdsourcing, and invisible enemies, this enthralling story makes more sense than ever.

The Occult, Witchcraft and Magic: An Illustrated History by Christopher Dell

From the days of the earliest Paleolithic cave rituals, magic has gripped the imagination. Magic and magicians appear in early Babylonian texts, the Bible, Judaism, and Islam. Secret words, spells, and incantations lie at the heart of nearly every mythological tradition. But for every genuine magus there is an impostor. During the Middle Ages, religion, science, and magic were difficult to set apart. The Middle Ages also saw the pursuit of alchemy—the magical transformation of base materials—which led to a fascination with the occult, Freemasonry, and Rosicrucianism. The turn of the twentieth century witnessed a return to earlier magical traditions, and today, magic means many things: contemporary Wicca is practiced widely as a modern pagan religion in Europe and the US; “magic” also stretches to include the nonspiritual, rapid-fire sleight of hand performed by slick stage magicians who fill vast arenas. The Occult, Witchcraft and Magic is packed with authoritative text and a huge and inspired selection of images, some chosen from unusual sources, including some of the best-known representations of magic and the occult from around the world spanning ancient to modern times.

#nonfiction#non-fiction#witchcraft#witchcraft books#the history of witchcraft#tbr#Reading Recs#book recs#recommended reading#to read#library#public library#history books#history

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

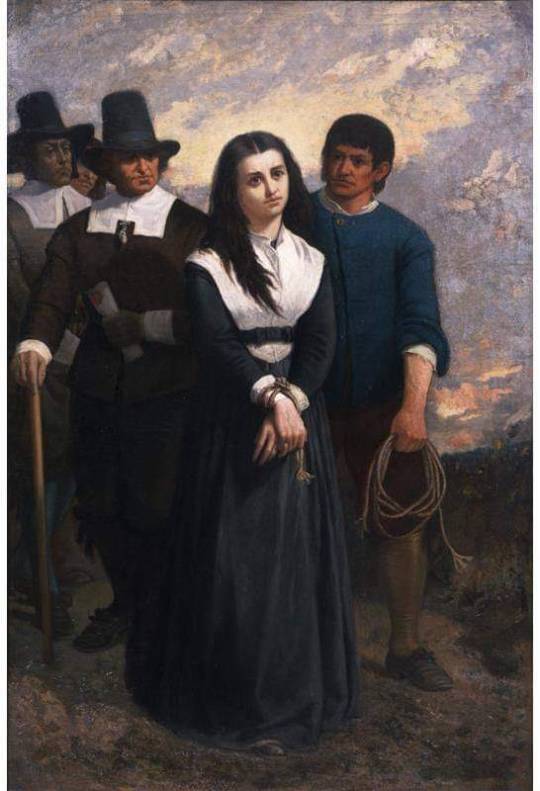

One of the darkest chapters occurred with the hanging of Bridget Bishop at Gallows Hill in Salem, Massachusetts for “certain detestable arts called witchcraft and sorceries" on June 10th, 1692.

To this day, despite the town’s openness to people of ever walks of life and being a safe haven for pagans and wiccans, the stigma of what occurred remains.

There have been countless analysis and retellings in the media about these witch trials. One (recent) theory that has gained a lot of traction is that besides fanaticism and want of attention, the girls’ hysteria was a product of wheat poisoning that was the result of a rye ergot –a hallucinogenic fungus.

The first person to offer proof of this was Linnda R. Caporael in 1976. Many historians have included her study in their assessment of this black chapter in American Colonial history. Among them is Stacy Schiff with her recent biography, “The Witches: Salem, 1692”.

A combination of mass hysteria brought about by this fungus and religious fanaticism is what culminated in the deaths of dozens of men and women falsely accused of witchcraft. Two hundred people were tried and close to twenty were executed –Bridget Bishop being the first.

Bridget Bishop was thrice married, first to Captain Samuel Wesselby from whom she had two children, then to a fellow widower, Thomas Oliver, from whom she had more children and finally to Edward Bishop, a prosperous sawyer. This last union produced no offspring.

Bridget Bishop’s accusers were five of the main afflicted girls: Ann Putnam, Mercy Lewis, Mary Walcott, Elizabeth Hubbard, and Abigail Williams two months before on the 19th of April. When she was brought before court, she was questioned by an equal number of men in whose eyes she was already guilty.

“The burden proof rested on the prosecution, but the prosecution enjoyed a few seventeenth-century advantages. An English trial of the time was inquisitorial, an informal, free-form, hectic, rapid-fire contest best described as “a relatively spontaneous bicker between accusers and accused.” Across the board, standards of proof were imprecise. A suspect had no idea of the evidence against her until she stepped into the courtroom, where she could be convicted of a different crime that the one for which she stood indicted. She had the right to defend herself but no guarantee she would be heard. Protests of innocence carried little weight …”

They wanted to hear her confession and reveal of other witches and warlocks. New England Puritan minister and science aficionado, Cotton Mather said in his later work “The Wonders of the Invisible World” that soon after the girls testified against her, other people showed up, presenting similar allegations. One of them was a middle aged man by the name of William Stacy who told the ministers that prior to her arrest, Bridget Bishop had told him that there were many in Salem who considered her a witch. Another man’s testimony followed his, accusing her of sending an affliction to his son.

“We know nothing of Bishop’s last words, of who tied her skirts around her ankles or her hands behind her back, who urged her up the ladder, placed the cloth over her head, or fitted the noose around her neck. Hangmen were not easy to come by. Sheriff Corwin may himself have delivered the push that left her suspended by the neck, thrashing desperately, twitching spasmodically, finally dangling, still and silent, in midair. She died by slow strangulation; the end could have taken as long as an hour. It was not necessarily quiet. It could be preceded by blood curling groans …

She died before noon; Corwin arranged for the corpse to be buried nearby, a detail he added to his report and later crossed out, presumably as he had exceeded his instructions. It is difficult to imagine who might have claimed the body. Bishop’s husband appears to have absented himself from the scene. From an earlier marriage, she had a twenty-five-year-old daughter, who could have kept her distance that season.

Across both Salems, villagers and townsfolk breathed a collective sigh of relief. They had dispatched a nuisance and a notorious sinner. Together they had engaged in a cathartic, calming ritual … such things were “painful, grotesque, but a scandal was after all a sort of service to the community.” The wise magistrates whose praises Mather sang in his charter-selling sermon … A decade earlier Bishop had pried a woman from her bed and nearly drowned her. The woman was thereafter insane, “a vexation to herself and all about her.” With Bishop’s arrest, her condition improved. And as Bishop swung from the gallows, the woman miraculous emerged from her decade of madness. The execution worked a spell of its own over Essex County, where –Mather would note- many “marvelously recovered their senses.” Accusations ceased over the next weeks, as did arrests …”

In the eyes of Puritan law, Bridget Bishop was beyond redemption, though there were those who still prayed for the good lord to bless their town and deliver them from evil. For a time, it seemed like God had answered their prayers but then the accusations resurfaced. The devil was still present and its agents hiding among them. People had to be vigilant and the ministers and judges act mercilessly against these offenders.

Source quoted: The Witches: Salem, 1692 by Stacy Schiff

Image: Posthumous painting of Bridget Bishop.

For additional information about the Ergo fungus, here's a link to a good article that is pretty straightforward: https://uh.edu/engines/epi1037.htm#:~:text=In%201976%20Linnda%20Caporael%20offered,when%20they're%20actually%20stoned.

25 notes

·

View notes