#sophie richie grainge

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Is there a difference between an icon and a trademark? What the Summer 2023 Barbie fashion party might tell us…

Well, summer is almost over, and, unless you’ve been on Mars (scratch that- you probably could have seen the sea of pink from space!), you’ve had or you've at least been living in the greater context of a Barbie-filled summer. You might have mixed feelings about this. As Vanessa Friedman put it, you might be “all pinked out” and never want to see another piece of Barbie-merch in your life. On the other hand, you might be like the countless other people celebrating the Barbie movie’s empowering message(s), its musical number for Ken, or just reveling in the fact that a film helmed by a woman director made over 1 billion at the box office. Whichever camp you fall into, there is one aspect of our Barbie-filled summer which has made all this celebrating, critique, and dress-up possible: intellectual property and, we might even say, its limits.

A central part of Margot Robbie’s promotion of the Barbie film has centered on how lucrative and full of potential the Barbie-world IP was/is; on how Robbie knew this while negotiating with Mattel and during the production of the film. As VOGUE reported in its Summer 2023 issue, Robbie observed, “The word [Barbie] itself is more globally recognized than practically everything else other than Coca-Cola.” (p. 82). And this emphasis on leveraging global recognition through Barbie’s IP fit Mattel’s own conception of itself as a company. As Ynon Kreiz, Mattel’s CEO, told The New York Times Magazine, “We used to think of ourselves and present ourselves as a manufacturing company…The specialty was: We make items. Now we are an I.P. company that is managing franchises.” (p. 26) But there is something important buttressing Kreiz’s characterization of Mattel as a company focused not on tangible products or items for sale but on the IP that makes those products/items possible: the cultural meaning of Barbie. Central in management’s mind is “[t]hat Barbie is not a toy; she is a pop-culture icon. That she does not have customers; she has fans. If you take that seriously, it outlines how to proceed. An icon who wants to stay at the center of the culture can’t keep putting out the same old thing and suing anyone who riffs on it. She has to stay current.”

And this points to a tension- and a question- that has implicitly animated and informed each one of our reactions, interpretations, and emulation of Barbie this summer. What is the difference between an icon and perhaps the strongest part of Mattel’s Barbie IP arsenal, a trademark? Does managing a cultural icon automatically mean a strong trademark on the market, or does having a cultural icon in your arsenal require ceding some proverbial trademark ground to your consumers or even to the public at large?

An icon is defined in a myriad of ways: it can be “a person or thing widely admired especially for having great influence or significance in a particular sphere”; an “emblem or symbol”, a sign, pictorial representation or image; or “a representation of sacred events or especially of a sacred individual (such as Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, or a saint) used as an object of veneration or a tool for instruction.” (For this last definition, I wouldn’t go so far as to compare Barbie to a saint, but the characterization of Barbie as a sacred individual is apt- haven’t we been venerating her since our childhoods? There may also be more to say about the woman/Virgin Mary/Barbie female triangle, but I digress…) The definition of “iconic” the adjective places even more emphasis on influence and significance and symbolism. Iconic is defined as “very famous or popular, especially being considered to represent particular opinions or a particular time”; “showing a relationship between the form of a sign, such as a word or a symbol, and its meaning”; and “of, relating to, or having the characteristics of an icon.” Complicating our common understanding of icon and iconic, however, is its ubiquitous use in, to name just a few,

the titles of creative works (looking forward to binge-watching what VOGUE deems “four iconic supers” in the Apple TV miniseries “The Supermodels” as I currently lose myself in PBS’ “Iconic America”)

marketing campaigns (I’m looking at you Fendi and the “iconic shape” of the Baguette not to mention less luxury fair like JCrew’s “iconic Edie bag”)

and on TikTok (Sophia Richie Grainge dancing to “Lifestyles of the Rich & Famous” sung by her brother-in-law was “iconic”), which we might even count as everyday conversation….

In some ways the definition of a trademark chooses a slice of the definition of an icon/iconic, protecting or extending a legal right to police the relationship between a sign and its meaning, which may include influence and fame. We might say that a trademark right effectively extends a legal right to the owner of a trademark to police the relationship between a word, name, symbol, or design and a specific message that it conveys to consumers- who produces the goods to which the mark is applied. And ideally this should not extend to who produces the ideas within the goods. As the holding in the Dastar case outlined “origin” in the phrase “origin of the goods” should not extend to “the person or entity that originated the ideas or communications that ‘goods’ embody or contain” but rather to “the producer of the tangible product sold in the marketplace” including “the actual producer, but also the trademark owner who commissioned or assumed responsibility for (“stood behind”) production of the physical product.” (p. 31- 32) Of course, trademark law also encompasses a number of other meanings and messages beyond who the producer of goods is, including who has sponsored or who is affiliated with the product. And with a claim like trademark dilution that goes beyond the concept of consumer confusion, trademark law (or, we might say trademark owner(s)) are arguably trying to claim a larger piece of the pie of meanings, messages, and symbolisms that exist between culture and commerce in their marks. And this should come as no surprise given the increasing role that managers of brands see themselves playing in culture. And as fashion, culture, and heritage continue to cross-pollinate (see the latest teasers and campaign for Fall/Winter 2023 Ferragamo fashion which showcase images of cultural properties and artwork in the Uffizi), we might more seriously consider reading fashion brands’ cease-and-desist letters and actions to police their trademarks in a wider cultural lens.

Do brands have a responsibility to police their marks while allowing for remixing, uses beyond those that are fair under the law, and even, perhaps, creations that may be trademark uses but communicate messages with which the brand would disagree (I'm looking at you Hermès)? And, to challenge Justice Scalia’s assumption, do consumers “who bu[y] a branded product… [at times]...assume that the brand-name company is the same entity that came up with the idea for the product, or designed the product”, especially if there is a marketing campaign that equates the producer or designer with the creation and dissemination of ideas embedded in the product? (p. 32) And might we, as consumers, care about who came up with the idea for a product as part of the meanings we identify with a trademark? The fact that we in fact do care might be the very reason we are so obsessed with authenticity on the fashion market in the first place.

The question of whether icon=trademark, or how these two terms overlap in a Venn diagram like space, is rife for more research and analysis (and is the topic of an academic paper I am currently finishing- full disclosure!). And there are some indications that “iconic” is doing potentially heavy lifting to convince judges and examiners that a brand has a strong mark, that a design has obtained secondary meaning, or is famous. In the VIP v. Jack Daniels opinion, iconic was used to describe the Jack Daniels mark at issue (“VIP sells products mimicking Jack Daniel's iconic marks and trade dress that mislead consumers….”) and Jack Daniels was described as only one of many “iconic brands” founded in the 19th century, among them Campbell’s Soup (pre-Warhol!), Quaker Oats, and Coca-Cola. (p. 3, 9-10). An early empirical observation that iconic is being imported into the application of trademark’s likelihood of confusion test and even into dilution actions raises questions about what legal weight we should give “iconic”, as a normative question (if we give it any weight at all). But there are some takeaways we might already observe about similarities and differences between icons and trademarks from our collective Summer 2023 Barbie fashion party. And central to those takeaways is the fact that we do seem to care about the ideas contained within the Barbie marks, whether registered or not. (For a deeper dive into Barbie's registered trademarks, and Barbie Pink as not yet registered in the United States see Rachael Dickson's great and informative videos and tweets).

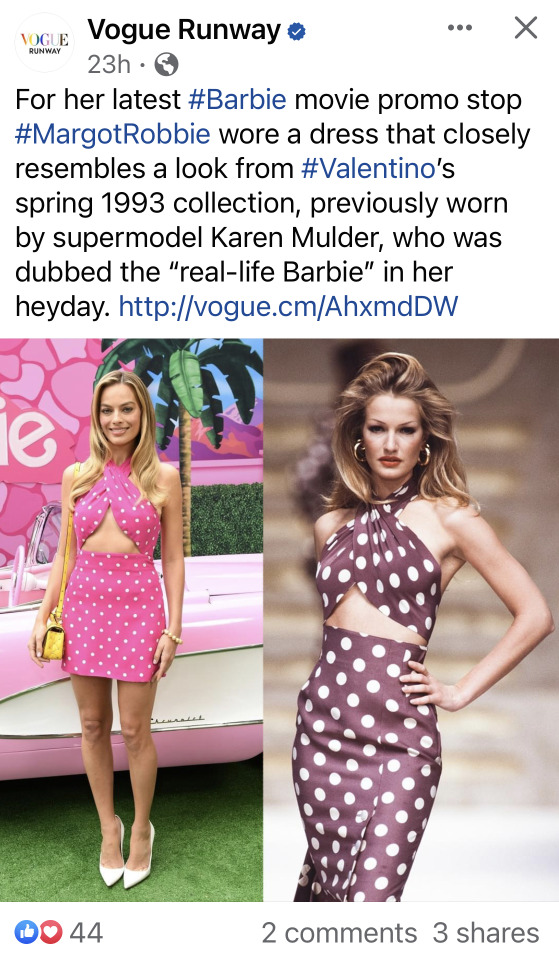

First, “iconic” has been part of the Barbie marketing campaign, especially during Margot Robbie’s red carpet re-interpretations of Barbie’s celebrated looks and fashion magazine’s editorials commenting on these re-interpretations (we might even call them copies). As Glamour put it “There’s no way we will ever forget how iconic all of Margot Robbie’s Barbie looks have been…” Side by side comparisons between Robbie’s iconic looks and the “iconic Barbie dolls that inspired them” beg the question of what meaning iconic has here. Are Robbie’s outfits iconic because they point back to the iconic Barbie outfit, thereby making consumers think of Mattel even though Mattel did not make the outfit Robbie is wearing? While some of Robbie’s outfits approximate Barbie’s outfits very closely (see Day to Night Barbie, 1985 compared to Robbie in a Versace Day to Night replica) others repeat a pink and gingham pattern in more freely inspired looks designed by Prada and Chanel, among others (I’m thinking of you two, Quick Curl Barbie, 1973 and Barbie Movie Barbie, 2023). What exactly is the symbol here within the fashion that is “iconic” of Barbie? If it is the entire outfit or design, iconic-icity might run up against the doctrine of functionality in trademark law if we were to contemplate whether the outfit/design could function as a trademark. If it is a combination of colors or the pink and gingham pattern, how do we conceive of secondary meaning in this case, especially when fashion brands known for using those colors or the color pattern in question have helped to create the outfit beyond the category of toys and in clothing? And Robbie’s outfits naturally bring Barbie’s outfits into 2023, with all the contemporary style and timeliness that implies (crimped hair aside, in this Pucci look, the headband was a no go). If a contemporary fashion outfit worn by Robbie is iconic of Barbie and indicates Mattel as its origin, what is the icon and what type of origin are we talking about? Is the icon/sign the idea of Barbie and the origin the cultural meanings we have caught up in the particular Barbies Robbie is citing? Or, is the icon/sign to which Robbie’s outfit is referring the particular Barbie doll product in its tangible form and the origin Mattel as a producer? With what would consumers say they most associate these contemporary fashion outfits? Is the answer Barbie the doll, Barbie the idea, or even, perhaps, Barbie the movie?

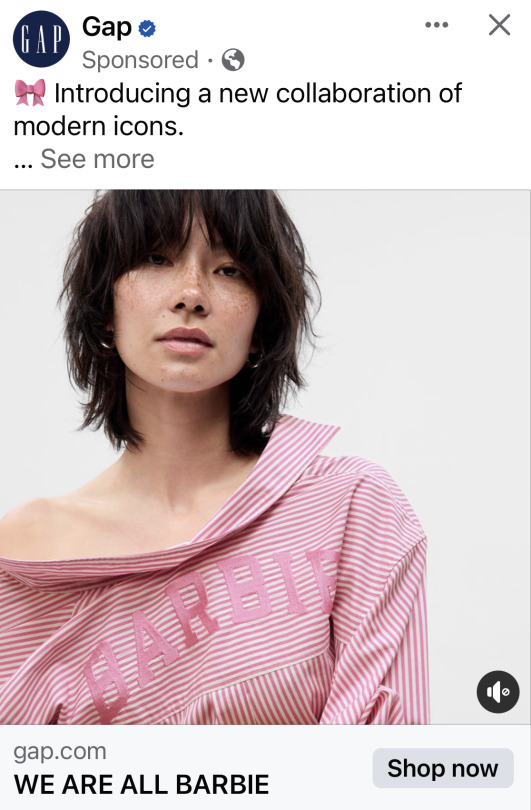

Complicating the question of what is the icon in Robbie’s replications of Barbie’s outfits are the added IP layers that the fashion brand collaborators bring to the table. Mattel’s multiple collaborations with fashion brands have blurred the lines between brand icons and Barbie icons. A whole fashion editorial team at VOGUE seems dedicated to spotting how fashion and luxury brands have referenced their own archives while catering to the Barbie universe (consider Valentino’s 1993 polka dots). Collaborations with still other, more commercial fashion brands and companies- a Barbie rug!- might seem to make Mattel’s trademarks more or just as recognizable as those of the fashion brand or other company with which it is partnering. Consider the Gap x Barbie collab described by Gap as “a new collaboration of modern icons.” Here, the word Barbie and Gap are prominent, and the color pink (whether in the Barbie Pink Pantone color or not) may only help to make these products particularly Barbie association prone. At the same time, however, collabs with brands that have historically used similar colors to Barbie Pink or that are now known on the market for their presence on a pink or Barbiecore aesthetic spectrum risk subsuming consumers’ identification of Mattel as the source of these products. Instyle may have said that “Greta Gerwig’s hot pink Valentino look at the Barbie premiere was MADE for this moment” but which comes first in consumers’ minds when they see Gerwig in this outfit at the Barbie premiere- Valentino the brand, Mattel the producer of Barbie, the idea of and the creative product generated by Barbie, or even more general emotional feelings linked to pink?

Of course, informing the question of what exactly is the relationship between icon and trademark in the context of the cultural and commercial Barbie universe is the fact that the more we dress up as Barbie, think pink, and embrace Barbiecore, the more cultural power we give to Barbie and to its producer Mattel. The more we have the freedom to dress in Barbie Pink to attend the Barbie movie (whether or not we buy and wear a dress or accessory created through a licensing deal with Mattel) the more iconic – very famous or popular – Barbie may become in our minds. We might think Barbie when we see any shade of pink, any pink polka dots, any pink and white gingham. But thinking Barbie does not necessarily mean thinking Mattel, and this is where Kreiz’s plan to manage Barbie as a pop-culture icon and not a toy comes full circle for the company's, but not necessarily the public’s, benefit. Expanding its presence from products on the market to ideas contained in films and music progressively expands Mattel’s IP portfolio and its presence in the minds of consumers whether the product they are selling benefits from IP rights or not. Even if the validity of a trademark right in a Barbie doll fashion design or Barbie Pink is questionable, it might not matter so much if everyone if wearing Barbie colors, watching Barbie the movie, and talking about the cultural meanings and gender roles contained in the idea of Barbie herself and the movie about her. In other words, icons might mean strong trademark rights on the market in certain circumstances, but having an icon and managing it “at the center of the culture” might lessen concerns about managing third party uses of marks in commerce at a more general level. And in this sense, culture might trump commerce or, at the very least, commercial might become cultural, and vice versa.

Further Reading

Kate Spade LLC v. Wolv, Inc., Opposition No. 91241442, TTAB, April 25, 2022

In re Max Mara Fashion Group S.r.l., Application Serial No. 87786944, TTAB, February 12, 2020

Nike, Inc. v. Honest E Online LLC, Opposition No. 91254139, TTAB, April 20, 2021

Cartier International A.G. v. Lance Coachman, Opposition No. 91209815, TTAB

Chanel, Inc. v. Camacho & Camacho, LLP, Opposition No. 91229126, TTAB, January 12, 2018

Marc Fisher LLC v. Bottega Veneta, Opposition No. 9121425314

In re Bottega Veneta International S.a.r.l., Serial No. 77219184, TTAB, September 30, 2013

TESS, Registration Number 4527371, Registration Date May 13, 2014

The Coca-Cola Company v. Robert Troy Hoff, Opposition No. 91244286, TTAB, May 14, 2021

“Hello Barbie” in VOGUE Summer 2023

Willa Paskin, “Plastic Fantastic” in The New York Times Magazine, July 16, 2023

Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. et al., 539 U. S. 23, 31 (2003)

https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2023-08-04/beyond-being-feminist-barbie-preaches-more-kenpathy

https://ruggable.com/collections/barbie-rugs-and-doormats?gclid=CjwKCAjw5_GmBhBIEiwA5QSMxCjYs2t9St9CvS8bYIWzBF8SPGbcONfjR_4rrZ-Aodu1FvyyG8gqmhoCJoMQAvD_BwE

Jeanne Fromer, "Against Secondary Meaning", 98 Notre Dame L. Rev. 211 (2022), https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol98/iss1/4/#:~:text=The%20dangers%20of%20enshrining%20secondary,meaning%20creates%20which%20hurt%20smaller

Graeme Dinwoodie, "Trademark Law as a Normative Project" (forthcoming in the Singapore Journal of Legal Studies)

instagram

Images

From references above and screen shots from Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok

#barbiecore#barbie#trademark law#color#barbie pink#margot robbie#barbie the movie#pink#iconic#iconic copies#likelihood of confusion#trademark dilution#valentino#prada#VOGUE#sophie richie grainge#greta gerwig#culture#creativity#fashion law#luxury law#chanel#IP law#films#creative products#creative industries#Instagram

1 note

·

View note