#sonya's st. petersburg

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

an evening with spencer reid…

your fingers laced around his wavy hair as a soft melody played in the background. his head was placed on your lap, fingers flipping through pages of a book, one in russian that would be impossible for you to understand. the smell of cookies flooded the living room, a tray of them on the counter as they cooled. you hummed along to the melody of the song. your fingers rake through his hair, messily intertwining them with his soft curls. you rub your thumb along his cheekbone, tracing his jaw before placing a kiss to his forehead.

“what’s the book about” you ask, a certain tenderness in your voice.

“its called crime and punishment, it tells the story of Rodion Raskolnikov, a destitute and intellectually gifted student living in St. Petersburg, he becomes obsessed with the idea of committing a "perfect" crime to prove his superiority and test his theory that some individuals are inherently above moral law. He meticulously plans and then murders an elderly pawnbroker, Alyona Ivanovna, believing that her wealth will be better used for the benefit of society. However, the murder haunts him, and he struggles to justify his actions to himself and everyone around him. He becomes increasingly isolated and tormented by guilt, exacerbated by the suspicions of police detective Porfiry Petrovich and the moral scrutiny of Sonya. As Raskolnikov's mental state deteriorates, he grapples with his conscience and the consequences of his actions. Ultimately, he is forced to confront the true nature of his crime and the depths of his own humanity. its really interesting!” he carried on with the storyline, explaining the complexity of the character. you listened attentively, nodding at every stop and smiling when he got so passionate and carried away. when he apologized for talking so much you just shook your head and pressed reassuring kisses all over his face. earning a smile from him and crimson cheeks.

#spencer reid fluff#spencer reid imagine#spencer reid angst#spencer reid x you#spencer reid#spencer reid x reader#criminal minds imagine#criminal minds fic#criminal minds

460 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crime and Punishment: Part 1 Analysis (Spoilers !!)

Characters:

Rodion Raskolnikov: 23 years old; ex student living in St. Petersburg; currently unemployed and very behind on rent; kind of a shut in

Alyona Ivanovna: pawn broker; capricious; undervalues the items brought to her; is abusive toward her younger half-sister; very rich

Lizaveta Ivanovna: younger half sister of Alyona Ivanovna; intellectually disabled; very "agreeable and uncomplaining" due to her disability and is pregnant often; cooks and cleans her sister's home; makes clothes; and cleans other's homes for a fee; gives all of her money to Alyona Ivanovna

Semyon Marmeladov: councilor; severe alcoholic; married to Katerina Ivanovna; was sober for one year but fired after drinking again; when the family moved and he found a new job, he was fired again; recently found his current job after begging a man for the position; after getting paid he took the money and spent it on alcohol and hasn't been home for five days; almost brags about his incompetence and how much it is destroying his wife, daughter, and step children

Katerina Ivanovna: second wife of Marmeladov; has three children from her previous marriage; sick; married Marmeladov "weeping and sobbing and wringing her hands" because she had nowhere else to go after her first husband died

Sonya Marmeladova: Marmeladov's daughter from his first wife; seems intelligent but was not able to make money doing handiwork and was bullied into prostitution by her step mother so that she could provide for the family

Nastasya: servant at the place Raskolnikov rents from; she seems to genuinely care about Raskolnikov, especially when he's sick

Praskovya Pavlovna: Raskolnikov's landlord; allegedly wants to get the police to evict him because he does not pay rent

Pulcheria Raskolnikov: Rodion's mother who sends him money to live off of, more so now that he has dropped out of university and stopped giving lessons for money: lives away from St. Petersburg, probably from the area the family is all originally from

Dunya Raskolnikov: Rodion's sister: younger than him: was a governess but the position was taken from her when the man of the household, Mr. Svidrigailov, kept trying to get her to have an affair with him and his wife saw; her reputation was ruined by Marfa Petrovna, his wife, and she and her mother were treated poorly by others; her reputation was saved when Mr. Svidrigailov told the truth and Marfa Petrovna's distant relative found out about Dunya through her story; the relative, Pyotr Luzhin, visited Dunya and Pulcheria and proposed to Dunya, which she agreed to; does not love Mr. Luzhin

Mr. Svidrigailov: the man who tried to preposition Dunya into an affair

Marfa Petrovna: wife of Mr. Svidrigailov; tarnished Dunya's reputation and kicked her out of their home after she found her husband trying to convince Dunya to be in a relationship with him; distant relative of Pyotr Luzhin

Pyotr Luzhin: 45 years old; relative of Marfa Petrovna, who told him about Dunya Raskolnikov; proposed to her the day after they met; arrogant; does not love Dunya; is open to meeting Raskolnikov and giving him a job at his business

Razumikhin: a former friend of Raskolnikov's from university; cheerful; friendly; well loved by others; physically strong; also left university for the time being

Themes:

Women Sacrificing Themselves to Save the Men They Love: seen so far in Sonya Marmeladova literally selling herself to provide for her father and her stepfamily, and Dunya Raskolnikov becoming, as Raskolnikov put it, "Mr. Luzhin's lawful concubine" to provide for her family, but mostly her brother; also, kind of seen in Lizaveta Ivanovna, although she does not sacrifice herself for a man, but her sister

Poverty: almost every character lives in poverty to some degree so far, besides Mr. Luzhin, Alyona Ivanovna and the Svidrigilovs, all for various reasons; for example, I believe Raskolnikov and Marmeladov are very different characters, but they are similar in the sense that they both rely on their female relatives to provide for them currently in the novel. There are other characters like Sonya, Lizaveta, Dunya, and Pulcheria who live in poverty because they give all or most of their money to someone else. There is also Katerina Ivanovna, who is ill and has to take care of her three young children, as cruel as she may be to Sonya. Razumikhin apparently had to leave university like Raskolnikov due to financial struggles, but we have not been told why

Morality of Criminality: It is revealed that the novel is asking us a question about crime when we hear Raskolnikov's reason for murdering Alyona Ivanovna: is one death worth it if it saves thousands of other lives? Raskolnikov believes so, but his crime goes wrong, and he ends up having to murder Lizaveta as well when he gets to their home too late, and she gets home before he can leave. Now he believes he has committed a crime, whereas before he thought that Alyona's death was a net positive for society. I wonder how his opinion on this will change as he processes what he has done or if the book will leave it up to us to decide for ourselves Christianity: during Marmeladov's story about his life he sort of compares himself to Christ, saying he should be crucified, etc. However, I believe Sonya is the more Christ-like figure in their dynamic in the way that she sacrifices herself for the greater good of her loved ones

Memorable Quotes:

"On that day He will come and ask, 'Where is the daughter who gave herself for a wicked and consumptive stepmother, for a stranger's little children? Where is the daughter who pitied her earthly father, a foul drunkard, not shrinking from his beastliness?' And He will say, 'Come! I have already forgiven you once…I have forgiven you once…And now, too, your many sins are forgiven, for you have loved much…'" (p. 41)

"'…It's clear that the one who gets first notice, the one who stands in the forefront, is none other than Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov. Oh, yes, of course, his happiness can be arranged, he can be kept at the university, made a partner in the office, his whole fate can be secured; maybe later he'll be rich, honored, respected, and perhaps he'll even end his life a famous man! And mother? But we're talking about Rodya, precious Rodya, her firstborn! How can she not sacrifice even such a daughter for the sake of such a firstborn son! Oh, dear and unjust hearts! Worse still, for this we might not even refuse Sonechka's lot! Sonechka, Sonechka Marmeladov, eternal Sonechka, as long as the world stands! But the sacrifice, have the two of you taken full measure of the sacrifice? Is it right? Are you strong enough? Is it any use? Is it reasonable? Do you know, Dunechka, that Sonechka's lot is in no way worse than yours with Mr. Luzhin?…" (p. 62-63)

"His thoughts were distracted…And generally it was painful for him at that moment to think about anything at all. He would have liked to become totally oblivious, oblivious of everything, and then wake up and start totally anew…" (p. 69)

"'…what do you think, wouldn't thousands of good deeds make up for one tiny little crime?…'" (p. 86)

#crime and punishment#book blog#bookish#bookblr#books#19th century literature#booklr#books and reading#classic lit#classic literature#russian literature#dostoevksy#fyodor dostoevsky#russian lit#russia#dostoevsky quotes#book quotes#classic lit quotes#I'm doing it in parts so I have stuff to post and also so I don't have to write as much at the end lol#I'm unsure of if certain words on here will get the post flagged but I hope not?#the post is educational?#idk man

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

spotify wrapped sounds cool!!

how about jamie and trevor and #83?

alright, so this wound up being the first song in a musical called "Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812" lol.....so it's au time!!!

[#83] Prologue (Cast of Great Comet)

There's a war going on out there somewhere /And Andrey isn't here

• Trevor (in all his protagonist glory) is our Natasha. "Natasha is young," and Trevor is naive. He sees the good in everyone. It takes Alex to keep him tethered to Earth, content to float up into the sky and dream his silly dreams.

• Alex is our Sonya ("Natasha's cousin and closest friend") - a realist who loves Trevor like a brother. He came to Moscow to also wait out his beloved fighting in the war (Cam). But he can't see everything Trevor does. Every sticky situation he gets himself into...

• That's what Quinn is for, our Marya—the Dad™️ of the group ("Natasha's godmother, strict yet kind"), wrangling the two youngins and knocking some sense into them as needed. No one disgraces the family name in his house!!

• And more important than Alex, perhaps, Trevor has Mason, our Andrey. Trevor thinks he loves Mason, and he's stuck in Moscow until this stupid war is over and he can be married and whisked away on a troika back to St. Petersburg, back to his proper life. But until then, "Andrey isn't here."

• And in comes our Anatole, Jack. "Anatole is hot": he's a wily, smooth-talking noble who can't keep it in his pants and wants that cookie (Trevor) so effing bad. He's stubborn and impulsive, but you gotta give credit where credit's due—he's determined.

• Cole would be our Hélène (Jack's "brother") because "Hélène is a slut," and Nick Suzuki would agree. Cole's the "queen of society" - everyone wants to be him, and everyone wants him. Including....Jack, cuz they have this weird eroticism going on (real brojobs at worlds type shit), so...

• Jack's partner in crime is Luke, our Dolokhov, "Anatole's friend, a crazy good shot," who enables Jack in all his dumb plans until the last second, when he's like "Okay dude maybe this is actually dumb". He has a thing for Cole...even though Cole is married! Though that didn't stop Jack.

• Jack swindles captures Trevor's heart and they create a proper scandal by snogging at the opera. And even though Jack is already married (fuck it; to Nico), he wants to elope with Trevor.

• And is this the life Trevor wants? Is this what love is? A whirlwind romance? Or will he find the life he wants with someone quieter....and caring....kind......

• like Jamie! Our Pierre ("Dear, bewildered, and awkward Pierre"), who has a lot of growth over this story. Jamie is at a crossroads. He's unhappy in his marriage to Cole, who despises him. He writes his letters to his best friend Mason, and feels guilty he can't fight in the war (due to his injuries). Trevor is a shining light in his life, but he never once considered there could be something more between them.

• What will happen? We'll have to see....

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

High School Lit Tournament Side A

War and Peace: A sweeping, romantic saga of two noble families and their intertwined destiny, and a panoramic portrait of Russian society at the time of the Napoleonic Wars, Tolstoy's unforgettable masterpiece has inspired love and devotion in its readers for generations.

Crime and Punishment: Raskolnikov, a destitute and desperate former student, wanders through the slums of St Petersburg and commits a random murder without remorse or regret. He imagines himself to be a great man, a Napoleon: acting for a higher purpose beyond conventional moral law. But as he embarks on a dangerous game of cat and mouse with a suspicious police investigator, Raskolnikov is pursued by the growing voice of his conscience and finds the noose of his own guilt tightening around his neck. Only Sonya, a downtrodden sex worker, can offer the chance of redemption.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Interesting Russian Novels

Crime and Punishment - Raskolnikov, a destitute and desperate former student, wanders through the slums of St Petersburg and commits a random murder without remorse or regret. He imagines himself to be a great man, a Napoleon: acting for a higher purpose beyond conventional moral law. But as he embarks on a dangerous game of cat and mouse with a suspicious police investigator, Raskolnikov is pursued by the growing voice of his conscience and finds the noose of his own guilt tightening around his neck. Only Sonya, a downtrodden sex worker, can offer the chance of redemption. (GoodReads)

Anna Karenina - Acclaimed by many as the world's greatest novel, Anna Karenina provides a vast panorama of contemporary life in Russia and of humanity in general. In it Tolstoy uses his intense imaginative insight to create some of the most memorable characters in all of literature. Anna is a sophisticated woman who abandons her empty existence as the wife of Karenin and turns to Count Vronsky to fulfill her passionate nature - with tragic consequences. Levin is a reflection of Tolstoy himself, often expressing the author's own views and convictions. (GoodReads)

The Brothers Karamazov - The Brothers Karamazov tells the dramatic story of four brothers Dmitri, pleasure-seeking, impatient, unruly… Ivan, brilliant and morose… Alyosha, gentle, loving, honest… and the illegitimate Smerdyakov, sly, silent, cruel. Driven by intense passion, they become involved in the brutal murder of their own father, one of the most loathsome characters in all literature. (GoodReads)

War and Peace - War and Peace broadly focuses on Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 and follows three of the most well-known characters in literature: Pierre Bezukhov, the illegitimate son of a count who is fighting for his inheritance and yearning for spiritual fulfillment; Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, who leaves his family behind to fight in the war against Napoleon; and Natasha Rostov, the beautiful young daughter of a nobleman who intrigues both men. As Napoleon’s army invades, Tolstoy brilliantly follows characters from diverse backgrounds—peasants and nobility, civilians and soldiers—as they struggle with the problems unique to their era, their history, and their culture. And as the novel progresses, these characters transcend their specificity, becoming some of the most moving—and human—figures in world literature. (GoodReads)

Dead Souls - Dead Souls is eloquent on some occasions, lyrical on others, and pious and reverent elsewhere. Nicolai Gogol was a master of the spoof. The American students of today are not the only readers who have been confused by him. Russian literary history records more divergent interpretations of Gogol than perhaps of any other classic. In a new translation of the comic classic of Russian literature, Chichikov, an enigmatic stranger and conniving schemer, buys deceased serfs' names from their landlords' poll tax lists hoping to mortgage them for profit and to reinvent himself as a likable gentleman. (GoodReads)

The Master and Margarita - An audacious revision of the stories of Faust and Pontius Pilate, The Master and Margarita is recognized as one of the essential classics of modern Russian literature. The novel's vision of Soviet life in the 1930s is so ferociously accurate that it could not be published during its author's lifetime and appeared only in a censored edition in the 1960s. Its truths are so enduring that its language has become part of the common Russian speech. One hot spring, the devil arrives in Moscow, accompanied by a retinue that includes a beautiful naked witch and an immense talking black cat with a fondness for chess and vodka. The visitors quickly wreak havoc in a city that refuses to believe in either God or Satan. But they also bring peace to two unhappy Muscovites: one is the Master, a writer pilloried for daring to write a novel about Christ and Pontius Pilate; the other is Margarita, who loves the Master so deeply that she is willing literally to go to hell for him. What ensues is a novel of inexhaustible energy, humor, and philosophical depth, a work whose nuances emerge for the first time in Diana Burgin and Katherine Tiernan O'Connor's splendid English version. (GoodReads)

Doctor Zhivago - This epic tale about the effects of the Russian Revolution and its aftermath on a bourgeois family was not published in the Soviet Union until 1987. One of the results of its publication in the West was Pasternak's complete rejection by Soviet authorities; when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958 he was compelled to decline it. The book quickly became an international best-seller. Dr. Yury Zhivago, Pasternak's alter ego, is a poet, philosopher, and physician whose life is disrupted by the war and by his love for Lara, the wife of a revolutionary. His artistic nature makes him vulnerable to the brutality and harshness of the Bolsheviks. The poems he writes constitute some of the most beautiful writing featured in the novel. (GoodReads)

Fathers and Sons - Bazarov—a gifted, impatient, and caustic young man—has journeyed from school to the home of his friend Arkady Kirsanov. But soon Bazarov’s outspoken rejection of authority and social conventions touches off quarrels, misunderstandings, and romantic entanglements that will utterly transform the Kirsanov household and reflect the changes taking place across all of nineteenth-century Russia. Fathers and Sons enraged the old and the young, reactionaries, romantics, and radicals alike when it was first published. At the same time, Turgenev won the acclaim of Flaubert, Maupassant, and Henry James for his craftsmanship as a writer and his psychological insight. Fathers and Sons is now considered one of the greatest novels of the nineteenth century. A timeless depiction of generational conflict during social upheaval, it vividly portrays the clash between the older Russian aristocracy and the youthful radicalism that foreshadowed the revolution to come—and offers modern-day readers much to reflect upon as they look around at their own tumultuous, ever changing world. (GoodReads)

Notes from Underground - A collection of powerful stories by one of the masters of Russian literature, illustrating the author's thoughts on political philosophy, religion and above all, humanity: Notes from Underground, White Nights, The Dream of a Ridiculous Man, and Selections from The House of the Dead. The compelling works presented in this volume were written at distinct periods in Dostoyevsky's life, at decisive moments in his groping for a political philosophy and a religious answer. From the primitive peasant who kills without understanding that he is destroying life to the anxious antihero of Notes from Underground—who both craves and despises affection—the writer's often-tormented characters showcase his evolving outlook on our fate. Thomas Mann described Dostoyevsky as "an author whose Christian sympathy is ordinarily devoted to human misery, sin, vice, the depths of lust and crime, rather than to nobility of body and soul" and Notes from Underground as "an awe- and terror- inspiring example of this sympathy." (GoodReads)

Heart of the Dog - This satirical novel tells the story of the surgical transformation of a dog into a man, and is an obvious criticism of Soviet society, especially the new rich that arose after the Bolshevik revolution. (GoodReads)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crime and Punishment Summary: Actions and Consequences Unraveled

Chapter 1 What's Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky

"Crime and Punishment" by Fyodor Dostoevsky is a novel that explores the moral and psychological consequences of committing a crime. The story follows Rodion Raskolnikov, a young and impoverished ex-student who murders a pawnbroker in an attempt to prove his theory that some people are above the law. As Raskolnikov grapples with guilt and paranoia, he is ultimately brought to justice and forced to confront the consequences of his actions. The novel delves into themes of morality, redemption, and the complexities of human nature. It is considered a masterpiece of Russian literature and a seminal work in the genre of psychological fiction.

Chapter 2 Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky Summary

Crime and Punishment is a novel by Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky that was first published in 1866. The novel follows the story of Rodion Raskolnikov, a young and impoverished former student living in St. Petersburg. Raskolnikov is consumed by a belief in his own intellectual superiority and becomes convinced that he is above the law.

Driven by his theory of the “extraordinary man” who has the right to commit crimes for the greater good, Raskolnikov decides to kill a pawnbroker and steal her money. After the crime, Raskolnikov is wracked with guilt and paranoia, and struggles to reconcile his actions with his conscience.

As Raskolnikov grapples with his moral crisis, he becomes entangled with a variety of characters, including his family, friends, a compassionate prostitute named Sonya, and a determined police detective named Porfiry Petrovich. Through these interactions, Raskolnikov begins to confront the consequences of his crime and ultimately finds redemption through suffering and repentance.

Crime and Punishment explores themes of morality, guilt, redemption, and the nature of good and evil. It is considered one of Dostoevsky’s masterpieces and a seminal work of Russian literature.

Chapter 3 Crime and Punishment Author

Fyodor Dostoevsky, a Russian novelist, wrote Crime and Punishment, which was first published in 1866. Dostoevsky is also known for other works such as The Brothers Karamazov, Notes from the Underground, The Idiot, and Demons.

Among Dostoevsky's works, The Brothers Karamazov is often considered his masterpiece and one of the greatest novels in world literature. It has been praised for its complex characters, philosophical themes, and intricate plot. In terms of editions, there are many acclaimed translations of The Brothers Karamazov, with the Constance Garnett version being a popular and widely respected choice.

Chapter 4 Crime and Punishment Meaning & Theme

Crime and Punishment Meaning

Crime and Punishment is a novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky that explores the psychological and moral dilemmas of a young man, Rodion Raskolnikov, who commits a murder and struggles with his guilt and redemption. The novel delves into themes of morality, justice, and the nature of evil, as well as the complexities of human nature and the consequences of our actions. It ultimately raises questions about the nature of punishment and redemption, and the possibility of finding meaning and salvation in a world filled with suffering and moral ambiguity.

Crime and Punishment Theme

One of the central themes in Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel "Crime and Punishment" is the idea of moral responsibility and redemption. The main character, Rodion Raskolnikov, commits a gruesome crime by murdering an elderly pawnbroker and her sister. Throughout the novel, Raskolnikov grapples with his guilt and ultimately comes to understand the consequences of his actions.

Another theme in the novel is the battle between good and evil within the human psyche. Raskolnikov is torn between his rationalization for committing the murder (the idea of the "extraordinary man" who is above societal laws) and his moral conscience. This inner conflict leads Raskolnikov to eventually confess to his crime and seek redemption.

The novel also explores the effects of poverty and social inequality on individuals. Raskolnikov's impoverished circumstances and his desperation to escape poverty are pivotal in driving him to commit the murder. Dostoevsky presents a bleak picture of 19th-century St. Petersburg, where characters struggle to survive in a harsh and unforgiving society.

Overall, "Crime and Punishment" delves deep into the complexities of human nature, morality, and the search for redemption. It serves as a timeless exploration of the human condition and the consequences of our actions.

Chapter 5 Quotes of Crime and Punishment

Crime and Punishment quotes as follows:

1. "The darker the night, the brighter the stars, The deeper the grief, the closer is God!"

2. "Man grows used to everything, the scoundrel."

3. "To go wrong in one's own way is better than to go right in someone else's."

4. "Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart."

5. "All is in God's hands."

6. "It takes something more than intelligence to act intelligently."

7. "We sometimes encounter people, even perfect strangers, who begin to interest us at first sight, somehow suddenly, all at once, before a word has been spoken."

8. "The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for."

9. "If you want to overcome the whole world, overcome yourself."

10. "I am a man because I err! You never reach any truth without making fourteen mistakes and very likely a hundred and fourteen."

Chapter 6 Similar Books Like Crime and Punishment

1. "To Kill a Mockingbird" by Harper Lee - This classic novel tackles issues of racial injustice, morality, and courage through the eyes of young Scout Finch as her father, Atticus, defends a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman in the Deep South.

2. "The Great Gatsby" by F. Scott Fitzgerald - Set in the Roaring Twenties, this novel follows the mysterious millionaire Jay Gatsby as he pursues his lost love, Daisy Buchanan, while exposing the emptiness of the American Dream in the glamorous world of wealth and excess.

3. "Pride and Prejudice" by Jane Austen - This beloved novel tells the story of Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy as their pride and prejudices clash, leading to misunderstandings, heartbreak, and ultimately true love in Regency England.

4. JD 塞林格的《麦田里的守望者》——这部成长小说讲述了幻灭的少年霍尔顿·考尔菲尔德在二战后美国经历青春期、疏离感和身份认同等复杂问题的故事,是一部永恒而又老少皆宜的读物。

Book bookey.app/book/crime-and-punishment

Author bookey.app/quote-author/fyodor-dostoevsky

Quotes bookey.app/quote-book/crime-and-punishment

The Great Gatsby bookey.app/book/the-great-gatsby

To Kill a Mockingbird bookey.app/book/to-kill-a-mockingbird

Youtube youtube.com/watch?v=yZVQk7j_Lw0

Amazon amazon.com/Crime-Punishment-Fyodor-Dostoyevsky/dp/0486415872

Goodreads goodreads.com/book/show/7144.Crime_and_Punishment

1 note

·

View note

Text

War and Peace 150/198 -Leo Tolstoy

141

The Rostofs remained in Moscow until September 13, the day before the enemy arrived, when Petya went to Byelaya Tserkov, the Countess felt a great fear. “The thought that both her sons had gone to war, that both had left the shelter of her wing, that today or tomorrow either one of them, or perhaps both of them, might be killed,”p.498 The Count had him transferred to Bezukhof’s regiment near Moscow so he’d be closer to her and had the hope of arranging it so he wouldn’t be sent away more and not be exposed to battle. (then why did you let the sixteen-year-old enlist) She loved her eldest more (because she’s that type of mother) but after her youngest also left she loved him now more than all her children and only wanted him and would not leave until he returned. He arrived on the nineth and wasn't pleased and so treated his mother coldly and only spoke to Natasha. (because he’s sixteen and still a brat)

Thanks to the Count’s characteristic unconcern nothing was ready to leave and had to postpone till the twelfth. Each day thousands of wounded and fleeing cluttered the streets and thanks to Rostopchin’s placards rumors were flying. The Count was scrambling the Countess was only concerned with Petya, only Sonya looked after the affairs, but she was melancholy lately after Rostof’s letter about Maria and the Countess’s excitement that the meeting was God’s providence. She wasn’t happy that Andrei was engaged to Natasha but Rostof with Maria will turn out wonderful. (this is the same family what’s so different now)

Sonya knew it would be an excellent match, (again it’s still the same haughty family) but she was bitter so took it upon herself the labor of preparations. The household was happy again for having a reason to be again. Petya left and returned a hero, and a possible battle any day. (that’s not something to be happy about) Natasha, because Petya was someone to admire her. “Moreover, she was happy, because there was someone who admired her-admiration was an absolutely essential lubricant if her ego was to function with perfect harmony,”p.500 (ah she’s the type that can’t handle it when the attention isn’t on her) Mostly they were happy because war had come to the city barrier, a great event in the air provides good spirits in people especially the young. (again this isn’t something to be excited about war is literally at your doorstep both your sons could die)

142

The house was turned upside down in preparation, Natasha sat in her empty room holding an out-of-style ball gown she wore to her first Petersburg ball. (it’s been what a few years how out of style could it be) She heard voices and looked out the window, a train of wounded were halted in the street, Natasha asked if they would like to stay in their empty house. She didn't ask her father, what difference would it make, but does ask her mother and father after they had already moved onto the lawn. (better to ask forgiveness than permission) They hurried to pack, shouting scolding and contradictory orders, Natasha almost cried because no one was in the mood to hear her quips. (see she’s like Rory from Gilmore Girls) When she did help with zeal it had to be done her way, but they grew confident in her management. That night more wounded were brought into the house, a valet brought in a man of great distinction, Andrei Bolkonsky.

143

It was an ordinary Sunday, at the Rostof house the disintegration of the life showed little and the demand of their valuables from others who wanted to escape Moscow. The major-domo had to leae the wounded behind. There weren't enough carriages for all, but the Count listened to an officer beg and had a few teams unloaded, what’s the hurry anyway. The Countess knew that tone which would cost them and made it her duty to oppose anything in that tone. She won’t consent to it, it’s the government’s job to look after the wounded, (and they deliberately suck at it) they’re idiots, everyone on the street already left, have pity on the children. Two teams had already been unloaded, Petya told her and Natasha became angry and went to her mother and told her it was shameful, to look in the ,so the Countess gave way. Natasha now gave orders, take only what they need and more wounded from other houses came to their yard and Sonya labeled things that were left behind and taken as much as possible.

144

By two, teams with the wounded already left and the family prepared to leave and said goodbye to staff that was staying. Out the window Natasha could see the passing carriages not knowing Andrei was in one. At Sadovaya they passed Sukhovet tower and Natasha saw Pierre and wanted to stop but they couldn't or hold up traffic. Pierre heard and ran over, he said he had to stay behind and Natasha wished she were a man to stay too and would if her mother would allow it. Pierre says looks like he was in battle, when asked why he isn't like himself says he doesn't know and farewell, Natasha kept a smile as they drove away.

145

In the two days since he left his home Pierre had been staring at the late Bazdeyef’s, at his home, when he was given his wife’s letter, he felt helpless and embarrassed. “All at once he realized that everything was now at an end, that ruin and destruction were at hand, that there was no distinction between right and wrong, that there was no future, and that there was no escape from this condition of things.”p.512 (feels a lot like the 2020s) A messenger came to get the late Bazdeyef’s things and the Frenchman with his wife’s message was anxious to see him. Pierre snuck out the back and went to Bazdeyef’s under the pretext of sorting his books and just sat in the study thinking for two hours. He had peasant clothes and a pistol sent for and several days later went with an old servant to Sukharef where he met the Rostofs.

Russian troops poured through Moscow all morning taking the fleeing and wounded. A few soldiers snuck into the Red Square to loot and in Gostinyi Dvor, merchants helped them carry off wares. Officers tried to round them up but the only way is to march faster so the rear can’t drop out, but there’s a halt at the bridge. Even merchants begged the officer protection in exchange for goods, the officer declared it’s not his business and rode to the front line.

146

For the most part the city was deserted, all night Rostopchin gave orders to the ceaseless men, someone had to take responsibility. By nine the troops were moving across Moscow and no one came for more orders. “All who could leave had left on their own responsibility; those who remained behind decided for themselves what they should do.”p.515 A crowd was waiting for Rostopchin at Sokohiki ready to be a mob for a victim. Rostopchin also wanted a victim for his wrath.

A man wearing chains stumbled on the steps and Rostopchin proclaimed he, Vereshchagin, had lost Moscow, a traitor who sold himself to Napoleon, take the law into their own hands, kill him. The crowd did,n't move the officers drew their sabers and a dragoon struck him with a dull broadsword, the shriek he gave triggered the mob. “The tense barrier of humane feeling which had held back the mob suddenly broke, The crime was begun, and it had to be accomplished.”p.518 The dragoons pulled Vereshchagin away as he was half beaten to death, the crowd only stopped in horror as he gave his death rattle, as his corpse was dragged away the mob surged away from it.

Instead of watching the crime Rostopchin went to his rooms, someone else had to lead him to his carriage and drive to Sokolniki. On the way he began to feel pangs of conscience and was dissatisfied at his terror he displayed in front of his subordinates. The populace is terrible and like wolves can only be appeased by flesh and he remembered Vereshchagin’s words there’s only one God above them. (he was only sentenced to hard labor not death) He told himself the people had to be pleased, other victims perished for the good of the public, he didn't reproach himself but found congratulations for taking advantage of circumstances. (on our day you’d be tried for murder) By the time he reached his house he was calm and didn't think of it only to yell at Kutuzof for deceiving him, Moscow was no more, the army is all that’s left. (what army) Kutuzof told him they are not giving up Moscow without a struggle, Rostopchin didn't reply and turned away to order along the teams blocking the bridge.

147

At four Murat’s troops entered Moscow followed by Wustemberg hussars and the King of Naples. They found cannons at the gateway when the walls of the Kremlin fell a flock of jackdaws rose above the walls and two Russians fired back, the firefight ended in four dead, three wounded and two fleeing. The French poured in Senate Square and made camp in the deserted mansions becoming marauders for five weeks. After they left Moscow, they fought to keep what they obtained and were doomed to perish as a monkey refusing to let go of a nut. The men became uncontrollable when finding pastured lands of an opulent city with its comforts and enjoyments. “The French attributed the burning of Moscow to the fierce patriotism of Rostopchin; the Russians, to the savagery of the French.”p.523 Really it was a timber-built city prone to fires before. “Moscow was burned but its citizens-that is true; not, however, by the citizens who remained, but by those who went away.”p.523

The French did not reach the quarter where Pierre was living until the fourteenth, after two days Pierre was near insanity by an idea to remain in Moscow and kill Napoleon, put an end to the misery in Europe. (a monster this large is a hydra cut off the head it won’t just die there will be a power grab and following chaos vacuum) His physical condition corresponded with his mental state sustaining on little food and vodka and little sleep. Pierre did not think of firing the shot or Napoleon’s death but only his own ruin and heroic courage, or perish and rehearsed the words to say in the moment.

148

Pierre decided until it was time he wouldn't disclose his identity on knowledge of the French, he stayed in the corridor as two French entered asking if the owner was home. The valet, Gerasim, struggled to understand and opened the kitchen door to reveal Bazdeyef’s halfwit brother Makar holding up a pistol. Before Pierre could stop him he fired at the Frenchmen ran to the door, Pierre flung away the pistol and ran after them. They listened to Pierre as he was French and let Makar be. They looked over the house and and Captain Ramball won over Pierre. He owes his life to Pierre and now owes favor, they ate and drank and the Captain spoke without cessation offering anything in friendship, Pierre refused so they drank more.

The Captain told Pierre about his ancestors, his family, childhood and estates and about all of his adventures, believing only he understood the delights of love. He holds in contempt sensual passion of his wife and romantic flame of Natasha that Pierre feels the Captain told his love of the trinity, five-year-old marquise and a seventeen year old maiden, the marquise’s daughter, the affair ending with the marquise deciding her lover should marry her daughter. (puking noises) Pierre listened to his stories and under the influence of wine comprehended it all and personal recollections connected and compared his love of Natasha to Captain Ramball’s. A story between love and duty, he saw himself at Sukharef, the meeting now seemed significant and poetic. Pierre told him how he could only love one woman who could never be his, him a bastard, her too young and told the Captain his whole story and even disclosed his name amazing the Captain he gave up everything to stay in the city. They gazed at the glow from the fire in the vast city, Pierre called it beautiful and stumbled to bed.

149

The fire was seen by various roads by escaping citizens and troops, the roads were so crowded the Rostofs had to stay at Mitishchi’s three miles from Moscow. The next day they again started late, with so many delays they got no farther than Bolshiya, by night the village of Maliya was set fire by Mamonof’s Cossacks, servants commented it looked like Moscow was burning. Natasha didn’t care to look and was in a stupor since finding out Sonya didn't tell her Andrei was one of the injured. The Countess urged Natasha to go to bed, they all but her readied and put out the lamp, there was still light from the street fire. Natasha didn't stir until everyone was asleep and walked outside to see Andrei, she had made up her mind that morning to see him but now filled with horror at what she might see. Other men were on the floor of the cottage, Andrei smiled and reached out to her.

150

It was a week since Andrei was in the hospital at Borodino in fevered anguish, losing consciousness when moved. Awake he asked for tea and spoke to Timokhin, he wanted the New Testament, the doctor promised to get one as he laughed over his wounds, the gangrene was spreading. In delirious agony Andrei begged for the book and suddenly remembered what happened to him and where he was and the man he hated being in the hospital and had happy obscure thoughts again, happiness found in the spirit of love. “but not that love which loves for a purpose, for a personal end, but this love which I for the first time experienced, when, dying, I saw the enemy and could still love him.”p.535 That divine love for one’s enemies, what became of him, he has hated many in his life but not loved and hated and Natasha.

Now he understood her and saw his cruelty with her, (now you do) he went back to delirium until he came to his senses and saw Natasha over him on her knees. She begged for forgiveness, Andrei told her he loves her and asked what does he have to forgive, (yeah she’s young and dumb but what’s your excuse) for what she did, he told her he loves her. The doctor sent her out and she fell on her bed sobbing. During all the rests on the journey, Natasha was by his side and even the doctor confessed he never expected such skill in nursing from a young girl. Despite the fact it would be terrible for Andrei to die in Natasha’s arms her mother couldn't refuse her. The couple didn't speak about if he recovered the engagement might be reestablished. “The undecided question of life and death which hung over not Bolkonsky alone, but over Russia as well, kept all other considerations in the background.”p537

NEXT

0 notes

Text

Today, we attended a fire show by a group known as Palyachi. They perform dances with fire sticks, and the show was indeed fiery, both literally and in the slang sense of the word. It's still too soon to change the hashtag from #YourGaluispampered; our Galu is still pampered.

To be fair, the music selection was quite good—pagan and fiery, fitting the theme well. However, the performance didn't quite live up to the music, although it seemed to appeal to the younger audience. We had seen them in Burgas a few years back. Sonya recalls enjoying it less than I did. But upon discussing it, we realized we had different branches of reality; I don't recall it like other. For me, this show was too slow.

Also, a note to anyone putting on a show: please refrain from inviting the mayor, your grandmother, your sponsor, your colleague, the second entertainer, or the show manager—or at least don't let them speak. Honestly, it's tedious and uninteresting. The audience doesn't care. They came to watch, not to listen, so the focus should be on the performance, not the speeches. And please, don't repeatedly solicit applause; it comes across as desperate. If the performance is outstanding, the audience will applaud on their own. There's no need for excessive bows or pleas for recognition. From the audience's perspective, it can seem quite unbecoming, as if you're begging for approval. Those who have come to see you likely already appreciate your work, but such behavior can detract from the experience. And that's the feeling that lingers after the show, even a successful one—the memory of how you pleaded and the perception that you weren't well-received.

However, the grand fire was impressive, and afterward, attendees were invited to jump over the fire for purification—an old Christian tradition, as the presenter informed us. The Bulgarians have their unique Orthodox practices, like slaughtering a lamb in the church, throwing a cross into the Sea for good luck, jumping over fires, weaving wreaths, walking barefoot in the dew to collect herbs, dressing as monsters, and singing from house to house—well-known Christian traditions, apparently. After leaping over the coals, we felt cleansed and blissful as we headed to our car.

An incident occurred when a girl spotted Ol, and it seemed as if her entire troubled fate flashed before her eyes, prompting her to lunge at Ol. From my perspective, I was leading Ol through the crowd when she suddenly reached out to stop a girl who, in desperation, was screaming and flailing, trying to grab onto Ol. I stepped forward to intervene, but Ol urged, "Let's get out of here quickly!" And so, I swiftly guided her away from the crowd. It's a dull story, recounting who offended whom, who made a misstep, who misunderstood, and who ended up in a mess.

But what's interesting is that we have some statistics. Several years ago, Lenochka visited a temple in St. Petersburg to seek blessings from some relics. It seems the blessings were granted, as on her way back, she intervened when a man was harassing a woman at a bus stop and beat shit out him. So, what I'm getting at is that Ol and Lenochka's creator - Mefis, must have a different understanding of blessing. How does one convey ideas in batches, as it's on a picture?

0 notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

SONYA WAKES UP ―

CW ― panic attack, intimate whumper, religious guilt

TIMELINE ― immediately (approx. 12hrs?) after Pyotr ‘rescues’ Sonya from his cabin

Sonya drifts towards wakefulness slowly. Memories dig at his mind, sharp fragments that hurt to think about: his father’s hands over his, helping him milk a cow. His brother ― a name that slips through his fingers ― weaving flower crowns in a meadow, laughing in sun-dusted glory. His mother working away at her lathe, showering him with scraps of sawdust.

Or perhaps they’re not his family at all. Perhaps they’re strangers. Perhaps ― the darkness is bigger than all three of them, bigger than him, yawning, gulping him into its black maw ―

He blinks. His eyelids are heavy. His body is sharp, and hot, and wrong. There’s light, light that hurts, light that burns― danger―

Trying to sit up, Sonya finds that he can’t. His limbs are weak, flimsy; he’s lying on a bed, and the sheets scrape against his skin, and he’s hot, he’s cold -- his chest heaves with terrified breaths, heartbeat dancing in his ears. Where is he?

A tiny, cramped room, one he doesn’t recognise from the shards of his past; it thrums and rattles beneath him, and he wonders whether it’s going to fall apart. Whether he’s trapped ― of course he’s trapped, rabbit in a trap, prey, he’s prey ―

His train of thought skitters to a halt when he notices the man, watching him from a chair. Again, not a face he knows, not his father: a tough, rock-cut face, dark eyebrows shadowing biting blue eyes. Sonya instincts label it a predator’s face, with a sharp, cruel mouth, only barely hidden by the man’s beard. Predator ― that makes him prey, food for this man, the hunter who’s trapped him, hobbled him.

Get out. That’s the only thought he can cling to. He thinks the man has spoken, but the words glance off his terror, subsumed by the need to go.

Scrabbling at the sheets, Sonya sits up, trying to drag himself off the bed. Oh, the world spins, head pounding fiercely, but he has to ― he needs to. He stumbles to his feet, trying to make those wobbly, aching legs do his bidding.

The man stands with him, whispering words Sonya can’t understand. They stare at each other, gauging: predator, prey. Hunter, hunted.

As the man reaches out, Sonya darts forward, towards the door. Get out, go, go, his mind screams, an animalistic desperation burning through him.

His legs won’t work, though. Stumbling, he careens into the man. No. No -- the man’s arms close around him, and Sonya’s chest tightens, raw instinct bubbling forward. He tries to bite the man, sinking teeth into his arm, thrashing desperately; a scream slides out around a leather sleeve, raw and desperate. No. If he can’t escape, he’ll be eaten. And he can’t ― he thrashes, fighting exhaustion, fixed bloody-mindedly on the door.

The man’s grip remains firm. Sonya’s lungs scream; he releases the man, howling, squirming desperately. No no no nonono. Now the man’s mouth is against his ear, tickling, whispering: shhh. But he can’t, he can’t just lie down and offer himself up, he can’t bear the thought of jaws around his throat ―

The memory. The memory, the memory― the―

At last, Sonya goes limp in the man’s arms, tears burning down his cheeks. He can’t fight it anymore: death comes for everyone. For lambs, brought to slaughter, for stupid little ― creatures ― who can’t run fast enough.

His breath comes in short gasps, waiting for the inevitable. The man maneuvers him back onto the bed, cradling him; Sonya can hear his heartbeat, slow, methodical, thumping under the dancing rhythm of his own.

Sonya waits for the final blow. The teeth. Feels the man’s breath flutter against his neck. Please, just do it quickly.

It doesn’t come. A moment trickles by, and all the man does is sigh.

“It’s alright, little one,” he says, voice a low rumble. “No more of that, please.”

“But ― you’re, you’re―” Sonya’s voice aches from disuse.

“I’m not going to hurt you, darling.” The man’s hand finds his hair, stroking through it gently. Part of Sonya hates himself for how easily he melts into it. “See?”

He whimpers. It would be so easy to trust. So easy, if there wasn’t the memory―

“Here, I know,” says the man. Sonya’s glad he can’t see his predator-face; his voice is steady. Grounding. “I’ll tell you a bit about me. Then you’ll have something of me.”

Sonya nods. He’ll agree to anything, if it doesn’t end with his innards splashed around the room.

“My name is Pyotr Vitalievich Zaytsev. I’m forty-six years old, and I live in St. Petersburg. I’m the governor, actually. My mother was from the Volga region.”

“Oh.” Sonya’s head aches with the effort of comprehension. St. Petersburg. The capital. Home of the Tsar. Volga. He feels like ― knows ― he should recognise it, but the meaning falls flat.

“What’s your name, little one?” Asks the man.

“Um―” the only one Sonya can think of is plucked from a half-memory, straight from his mother’s lips. “Sonya.”

“Ah.” There’s a note of disappointment in Pyotr’s voice. “So you’re not―”

“I, I, I am a boy.” It just slips out; now Sonya understands why his body feels so wrong. That, at least, is a piece of the puzzle the fragments can solve.

“Thought so.”

Between Pyotr’s steady hand and the rocking of the room, Sonya feels drowsiness begin to creep up on him. Yet the uneasiness remains, gnawing away at his insides. Reminding him there’s so much he doesn’t know.

“Where― where, where are we?”

“On a train to St. Petersburg, darling.” The way Pyotr says darling, equal parts fondness and amusement, makes something pathetic flare in Sonya’s chest.

“Oh.”

In the silence, he feels so terribly out of place. Wrong, in his own skin, and not just because his body doesn’t fit. Everything’s too sharp, too clean cut ― every time his tongue moves in his mouth, it’s confronted with the sharpness of his canines.

Fangs. The memories don’t attest to them.

“What, what am I?” He almost doesn’t want to ask.

“An upyr, my little one.” Pyotr says it with such loving revulsion that a shiver dances over Sonya’s skin.

“Upyr,” Sonya repeats, feeling it out. Vampire. Unholy ― the thought twists his stomach, sets his heart skittering a little faster. Unholy and disgusting. “I’m―”

“Damned.” Pyotr speaks the word Sonya doesn’t dare to, the word that makes him feel sick. “I know, little one, but it’s alright― I’m here to save you.”

“Please.”

Pyotr just hums, tangling his fingers in Sonya’s hair. His nails scrape gently along his scalp, eliciting a moan of pleasure.

“It’ll be alright,” he murmurs, “You’ll be home soon. You’ll be safe. All you need to do is trust me.”

Of course, Sonya does.

#panic attack tw#whump#creepy whumper#intimate whumper#captive whump#psychological whump#religious trauma tw#vampire whump#supernatural whump#vampire whumpee#supernatural whumpee#sonya's st. petersburg#sonya petrovich zaytsev#pyotr vitalievich zaytsev

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich: Part 2- Background and Beginnings

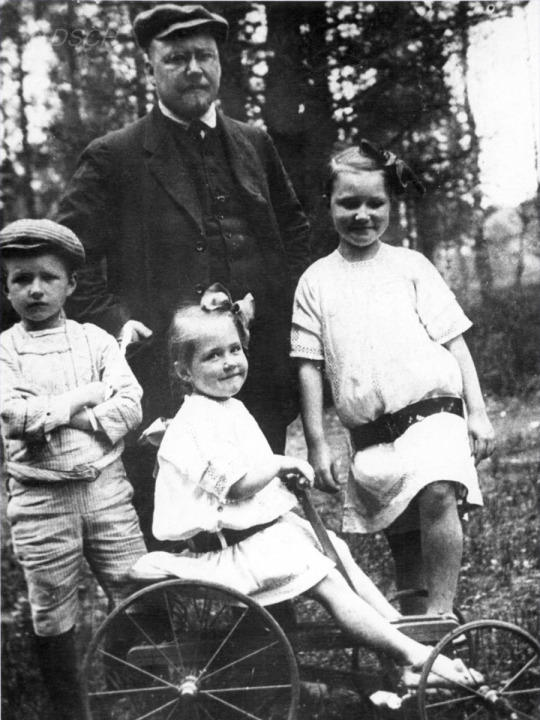

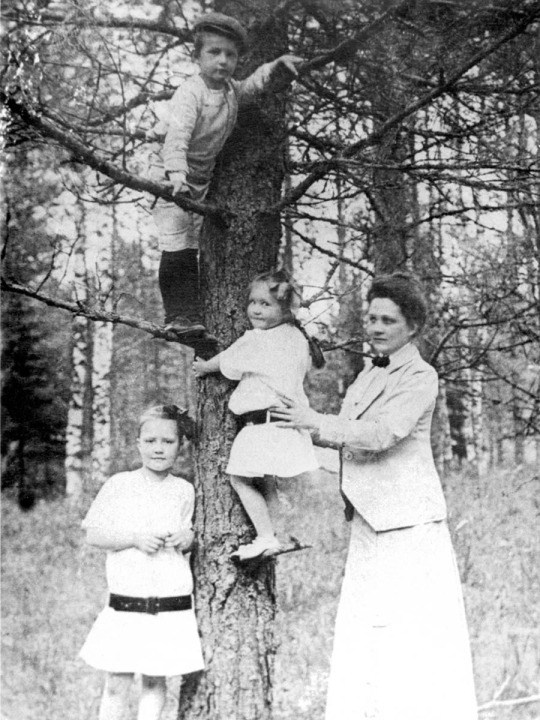

Hello, and welcome back to Tumblr's Guide to Shostakovich, the series where I talk about the life and works of Dmitri Shostakovich! Today, I want to talk some about his family background, and about his childhood. The main sources I'll be using for this post are Dmitri Shostakovich: The LIfe and Background of a Soviet Composer by Victor Seroff and Nadezhda Galli-Shohat (who was Shostakovich's aunt), Pages From the Life of Dmitri Shostakovich by Dmitri and Lyudmila Sollertinsky, and Shostakovich: A Life Remembered by Elizabeth Wilson. Photos are from Dmitri Shostakovich: The Life and Background of a Soviet Composer and the DSCH Publishers website.

Dmitri Shostakovich was born on September 25, 1906, to Dmitri Boleslavovich and Sofiya Vasiliyevna (nee Kokaoulina) Shostakovich in St. Petersburg, Russia. His maternal grandfather, Vasiliy Jakovlevich Kokaoulin, hailed from Siberia and advocated for improved working conditions for miners in the Lena Gold Field, where he became the manager. Sofiya Vasiliyevna was one of six children, and studied music at the Irkutsk Institute for Noblewomen; her brother Jasha became involved with the growing revolutionary movement. When a student protest on Kazan Square in February 1899 was violently disbanded by armed Cossacks, Sofiya and her siblings became more deeply sympathetic towards the revolutionaries; her sister Nadezhda Galli-Shohat would become a member of the Social Democratic Bolshevik Party (she would later come to disagree with Bolshevism and emigrate to the United States in 1923).

(Sofiya Vasiliyevna Shostakovich, the composer's mother. 1911.)

Shostakovich's father, Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, came from Polish origins ("Shostakovich" is actually a Russification of the Polish surname "Szostakowicz.") and worked as a senior keeper at the Palace of Weights and Measures. His father, Boleslav, was deeply involved in the Polish revolutionary movement, and organized the release of Jaroslav Dombrovsky, who had been imprisoned due to his part in the Polish Uprising. As a result, Boleslav was exiled to Siberia. (Side note- Shostakovich's first name was nearly "Jaroslav," but the Orthodox priest at his christening advised his parents to name him "Dmitri," after his father.)

(Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, the composer's father. 1903.)

(The composer around age one and his sister Maria ("Marusya"), 1907.)

By the time Shostakovich's parents were raising their three children in a middle-class household on Nikolaevskaya Street, revolutionary sentiments were sharply rising; Shostakovich himself was born just a year after the "Bloody Sunday" massacre of 1905. However, another major component of the artist young Mitya Shostakovich would become was highly present in their home- music. His mother was a skilled pianist, and his father- a "kind, jolly man" who would sing to her accompaniments. Shostakovich would listen to his neighbour, Boris Sass-Tisovsky, play the cello, and the Shostakoviches would take their children to the opera. Seroff and Galli-Shohat include an anecdote illustrating the contrasting personalities of Sofiya and Dmitri B. Shostakovich: "Sonya [Sofiya] gradually weeded out most of the Siberian friends of Dmitri's [Boleslavovich] student days because, for her, there was too much of the "muzhik" [term for a male peasant] about them and in these days she sought a different society. Dmitri took all this reform very good-naturedly and only retained, in spite of all that Sonya could do, his heavy gait and his rough, Siberian-peasant way of speaking. Sonya would have despaired of his slangy speech except that she knew his gay and lovable disposition always won him friends wherever he went. "Sonya, Sonya," he would say, shaking his head and looking at her over the top of his glasses, "I'm a bad one. Squirt me another glass of tea."

(Mitya, Maria, and Zoya Shostakovich with their parents, 1912.)

Despite an early recognition of his talents as a prodigy, Shostakovich was never pressed into music unwillingly; for the most part, he had a happy childhood with his sisters Zoya and Maria, gathering mushrooms, reading adventure books, and watching their father play solitaire (which would later become one of Shostakovich's favourite pastimes as well). However, at the age of nine, after attending a performance of Mussorgsky's The Tale of Tsar Saltan, Mitya was able to recite and sing most of the opera from memory the following day. That summer, in 1915, he began piano lessons. Among his first childhood works was the "Funeral March for Victims of the Revolution;" he recalled that he "composed a lot under the influence of external events," a trait that would come to follow him throughout his future career. He took lessons from Ignati Glyasser, and later Aleksandra Rozanova. By the time he entered the conservatoire at age thirteen, the city he was born in had been renamed to Petrograd; WWI had meant a Russification of the name "St. Petersburg" due to anti-German sentiment. In 1924, it would once again be renamed "Leningrad," following the death of Vladimir Lenin. (Today, the city is once again called "St. Petersburg," following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.) Shostakovich's enrollment was on the recommendation of the composer and professor Aleksandr Glazunov, who would play a highly significant role in his conservatory years.

(Aleksandra Aleksandrovna Rozanova, Shostakovich's piano teacher.)

(Ignati Albertovich Glyasser with his piano class, 1917. Dmitri Shostakovich is located second from the right in the first row; Maria Shostakovich is located fourth from the right in the second row.)

In the next few entries, I will talk more about his adolescence and conservatory years, along with some drama in his personal life. ;) See you then!

#dmitri shostakovich#classical music#music history#soviet history#russia#classical music history#composer#russian history#shostakovich#tumblr's guide to shostakovich

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday Wisdom: Selected Books of the week!

A world is not complete without books. Books teach readers about both the problems and the ways of life. There is no companion as faithful as a book, as Ernest Hemingway once wrote. Every student's life is fundamentally impacted by books because they open their eyes to the realm of imagination. Here are some of the week's top books. 1. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or as it's known in more recent editions. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, is a novel by American author Mark Twain. And that was first published in the United Kingdom in December 1884 and in the United States in February 1885. A nineteenth-century boy from a Mississippi River city recounts his adventures as he travels. Down the swash with a raw slave Encountering a family involved in a feud, two scoundrels pretending to be kingliness. And Tom Sawyer's aunt who miscalculations him for Tom. 2. Beloved by Toni Morrison Beloved is a 1987 novel by American novelist Toni Morrison. Set in the period after the American Civil War, the novel tells the story of a dysfunctional family of formerly enslaved people whose Cincinnati home is visited by a malignant spirit. This book is a Winner of the Pulitzer Prize, Toni Morrison’s Beloved is a spellbinding and brightly innovative portrayal of a woman visited by history. 3. The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer The Canterbury Tales is a collection of twenty- four stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. It's extensively regarded as Chaucer's magnum number. The procession that crosses Chaucer's runners is as full of life and as plushly textured as a medieval shade. The Knight, the Miller, the Friar, the Squire, the Prioress, the woman of Bath, and others who make up the cast of characters-- including Chaucer himself-- are real people, with mortal feelings and sins. When it flashed back to Chaucer writing in English at a time when Latin was the standard erudite language across Western Europe, the magnitude of his achievement is indeed more remarkable. But Chaucer's genius needs no literal preface; it bursts forth from every runner of The Canterbury Tales. 4. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor M Dostoyevsky Crime and Punishment is a novel by the Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky. It was first published in the erudite journal The Russian Messenger in twelve yearly inaugurations during 1866. And later on a single volume has published. Raskolnikov, a destitute and hopeless former pupil, wanders through the slums of St Petersburg and commits an arbitrary murder without guilt or remorse. He imagines himself to be a great man, a Napoleon acting for an advanced purpose beyond conventional moral law. But as he embarks on a dangerous game of cat and mouse with a suspicious police investigator, Raskolnikov is pursued by the growing voice of his heart. And finds the mesh of his own guilt tensing around his neck. Only Sonya, a crushed coitus worker, can offer the chance of redemption. Read the full article

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

High School Lit Tournament Round 2A

Crime and Punishment: Raskolnikov, a destitute and desperate former student, wanders through the slums of St Petersburg and commits a random murder without remorse or regret. He imagines himself to be a great man, a Napoleon: acting for a higher purpose beyond conventional moral law. But as he embarks on a dangerous game of cat and mouse with a suspicious police investigator, Raskolnikov is pursued by the growing voice of his conscience and finds the noose of his own guilt tightening around his neck. Only Sonya, a downtrodden sex worker, can offer the chance of redemption.

Animal Farm: A farm is taken over by its overworked, mistreated animals. With flaming idealism and stirring slogans, they set out to create a paradise of progress, justice, and equality. Thus the stage is set for one of the most telling satiric fables ever penned –a razor-edged fairy tale for grown-ups that records the evolution from revolution against tyranny to a totalitarianism just as terrible.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wise Beyond Her Years

summary: Pierre realizes he’s in love with his childhood best friend

pairing: Pierre Bezukhov x reader

word count: 1,489

warnings: fluff, soft Pierre moments

My dearest (Y/N),

Helene has become unbearable. She admitted to not wanting children although I persuaded her with having any amount of money she could ever want. I would like children one day, maybe Helene isn’t meant to be in my life after all. Thank you for listening.

Pierre Bezukhov

—————————————

As you carefully read Pierre’s letter, you cannot help but feel his unhappiness. He didn’t even originally want to marry Helene, her father thrust marriage upon them.

You’d known the man since you were children, you always felt a growing sense of love when you saw him but it was much more than a friendly love, it was a romantic one.

Once Pierre had come into the sum of his father’s inheritance, women were falling over themselves to get to him. It’s as if the socially awkward man they once saw had been erased from their minds.

He was still your Pierre though, the man that you loved and had since childhood. Your heart leaped anytime you saw him, but that was long ago. After getting thrown out of St. Petersburg, you hadn’t seen him in many months.

Once you received his letter, you immediately wrote back.

—————————————

Pierre,

I’m sorry to hear about your misfortune with Helene. Just know that there is a silver lining to your problems, my dear. You must come visit me, I get lonely most days without you here. The ice has frozen solid over the lake, it is now perfect for ice skating.

(Y/N) (L/N)

—————————————

The wind whipped through your hair as you skated across the frozen lake. Your warm coat kept out the cold. You skidded to a halt as you saw a figure in a fluffy ushanka marching towards you. It was Pierre, your Pierre.

He rushed towards you, nearly falling on his face. You met him in the middle, squeezing him tightly in a hug.

“Pyotr! So good to see you.” You exclaim, your mouth buried in the fur of his coat.

“Dearest (Y/N), it has been too long.” He mumbles into your hair as you pull away to look at him, your hands on his forearms.

“Come, let me show you how to skate.” You carefully pull him onto the ice with you as you skate backward, your eyes remaining on him. His gaze is wary as he slowly begins moving on the frozen water.

“This is much more fun than I ever anticipated.” He laughs softly as he looks down at his feet.

*******

Once you both return to the warmth of indoors, you take off your coat. You run your hands down the length of the smooth fabric of your dress. A soft sigh escapes your lips as you sit down next to the fire, the only sound being the popping of the fire.

“How have you been, (Y/N)?” Pierre startles you with his voice as he sits down in a chair next to you.

“Oh my! You gave me a fright.” You laugh softly as you put a hand to your chest.

“I’ve been lonely, Sonya and Natasha keep fine company but I miss our talks. I miss the way you used to make me laugh.” Your eyes flit to him, taking in his appearance. His hair a little longer than what you remember although the same glasses adorn his face.

“I see. I’ve missed you too, dearly. Helene only thinks of me as an oaf and a brute. She’s decided that she won’t mother any children either. The words she used were ‘you know I’m not the motherly type.’” He sighs, running a hand over his face.

“You deserve someone who will treat you better, Pierre. A kind woman who will happily bear your children.” You gently take his hand, he looks down at it. His eyes turn to you as he moves your hand up to his lips, kissing it softly.

Your breath catches in your throat as you turn to look away, your cheeks dusted with a faint blush.

“Pierre, you always flatter me.” You whisper as a smile graces your lips.

“You know that I’ve always found you to be wise beyond your years. You’re extraordinary! I’m four years your senior and yet you could outsmart me in almost any situation.” He’s doting on you now, making wild gestures with his hands. It always humored you when he became over dramatic.

“Oh, stop it Pierre. You’re too kind.” You laugh softly as he stands up, pulling you with him by your hands.

“It beguiles me that you can’t see your worth. You deserve a good man, (Y/N).”

*******

Pierre begins writing to you once more after he sees you. He would tell you about how many times Helene would be out and about and how each time he was more and more tempted into divorcing her.

The straw that broke the camel’s back was the truth of him finding out that Fedya Dolokhov, his own friend, was having an affair with Helene. Her restless behavior when he was around made sense now.

Pierre had challenged Dolokhov to a duel, in which he won. It was a miracle that he remained unscathed through it all. He wrote to you about his good fortune and each day after that. He began writing so often that you couldn’t keep up.

—————————————

My dearest (Y/N),

There is a ball being held soon. I would hope that you would be in attendance. This will be one of the first times that I make an appearance in public after separating from Helene. Please consider my proposal.

Pierre Bezukhov

—————————————

The thought of seeing Pierre again enticed you enough to bare the festivities of aristocratic life. With a heavy sigh, you prepared for the ball that’s taking place in the evening.

*******

The gold that lined the walls of the palace was illuminated as the darkness from outside seeped in. Everyone looked regal in their white clothes, especially the girls who lined up to meet their suitors.

You stood by your lonesome with your parents at your side as you surveyed the crowd. Andrei was somewhere in the crowd along with Pierre. You followed their gaze to see Natasha playfully looking away from their watchful eyes.

You felt wrong for coming, you felt like a fool. Of course Pierre could never love you when he was always so close with Natasha. Tears filled your eyes as you rushed off to another part of the palace, leaving your parents and the emotions of the ballroom behind.

You cried softly as you sunk to the floor, the only other bodies in the room being that of the footmen. The sound of boots against the tile filled your ears as you remained in your previous position.

“(Y/N)? Are you alright? What is the matter?” Pierre squatted down to your level as he beckoned you to look at him.

“I saw the way you looked at her, you love her don’t you?” You sniffled as you whipped your head up to look at him.

He opens his mouth to speak before closing it again, at a loss for words.

“...Never mind.” He stands up again as he begins to pace the small space.

“Never mind what? What is it, Pierre?” You demand as you approach him.

“I don’t love her, I love you.” He blurts out, his eyes a mix of fear and sadness.

You choose your words before vocalizing them.

“I love you too, Pierre. Ever since we were little.” You whisper the last part, staring at your shoes. He pulls you closer to him, his hands on either side of your face. He leans down and captures your lips in his own. The kiss is tender and soft as your lips move together as one.

Once you finally part, you feel as if a weight has been lifted off your shoulders. Your feelings no longer harbored, now out in the open.

“I’m delighted to hear that you feel the same way. Now, might you allow me the honor of dancing with you? If you’ll have me, that is.” He holds out his hand to you. You take it without a second thought, his deft, gloved fingers warm in your own.

He leads you out to the ballroom, this time your view of it is different. The faces seem a little more welcoming and you now notice just how handsome Pierre looks in his pale grey jacket. His eyes never leave yours as he holds you close. A slow melody fills the air as you hold him close.

Your hand in his, the other on his shoulder. You feel peace for the first time in years as you gaze at the man who loved you in return. That’s all you ever wanted in the end, is to be loved and love in return.

This was just the beginning of your new life with Pierre. Just the start of something wonderful.

#paul dano x reader#paul dano#pierre bezukhov#pierre bezukhov x reader#war and peace 2016#war and peace

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ten Interesting Russian Novels

Crime and Punishment - Fyodor Dostoevsky

Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov, a former student, lives in a tiny garret on the top floor of a run-down apartment building in St. Petersburg. He is sickly, dressed in rags, short on money, and talks to himself, but he is also handsome, proud, and intelligent. He is contemplating committing an awful crime, but the nature of the crime is not yet clear. He goes to the apartment of an old pawnbroker, Alyona Ivanovna, to get money for a watch and to plan the crime. Afterward, he stops for a drink at a tavern, where he meets a man named Marmeladov, who, in a fit of drunkenness, has abandoned his job and proceeded on a five-day drinking binge, afraid to return home to his family. Marmeladov tells Raskolnikov about his sickly wife, Katerina Ivanovna, and his daughter, Sonya , who has been forced into prostitution to support the family. Raskolnikov walks with Marmeladov to Marmeladov’s apartment, where he meets Katerina and sees firsthand the squalid conditions in which they live. (https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/crime/summary/)

Fathers and Sons - Ivan Turgenev

Bazarov is a young, cynical man, and he prides himself on his self-proclaimed nihilist outlook on life. He is a complete turnaround from his father and the previous generation as he strongly rejects their romanticized lens of society. Bazarov’s controversy comes as he chooses to forego the age-old traditions of the society he was born into and his father celebrates. (https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/crime/summary/)

Dead Souls - Nikolai Gogol

Set in Imperial Russia, the plot of Dead Souls follows scandalized government official Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov as he manipulates the inefficiencies of the Imperial Russian government by purchasing the rights of dead serfs from middle-class landowners to amass a personal fortune. The golden thread that ties the disparate, episodic encounters that comprise Gogol's picaresque novel together is the purchase of dead serfs, also called dead souls. The Russian government taxed landowners according to the number of souls on a property. The infrequent nature of official censuses meant that landowners were often taxed for deceased serfs. The following sections are a summary of the book Dead Souls. (https://study.com/learn/lesson/dead-souls-by-nikolai-gogol-summary-analysis.html)

A Hero of Our Time - Mikhail Lermontov

A Hero of Our Time - Mikhail Lermontov

Grigory Pechorin is a bored, self-cented, and cynical young army officer who believes in nothing. With impunity he toys with the love of women and the goodwill of men. He impulsively undertakes dangerous adventures, risks his life, and destroys women who care for him. (https://www.britannica.com/topic/A-Hero-of-Our-Time-novel-by-Lermontov)

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich - Alexander Solzhenitsyn

A wake-up call sounds in a Stalinist labor camp in 1951, on a bitterly cold winter morning. Ivan Denisovich Shukhov, a prisoner in Camp HQ, is usually up on time, but this morning he suffers a fever and aches, and yearns for a little more time in bed. Thinking that a kindly guard is on duty, he rests past the wake-up call a while. Unfortunately, a different guard is making the rounds, and he punishes Shukhov for oversleeping with three days in the solitary confinement cell, which the characters call “the hole.” Led off, Shukhov soon realizes that the sentence is just a threat, and that he will only have to wash the floors of the officers’ headquarters. Shukhov removes his shoes and efficiently completes the job, proceeding quickly to the mess hall, where he worries he has missed breakfast. He meets the sniveling Fetyukov, a colleague who has saved Shukhov’s gruel for him. After breakfast, Shukhov heads to sick bay to get his fever and aches examined. The medical orderly, Kolya, tells him he should have been ill the previous night, since the clinic is closed in the morning. Shukhov’s fever is not high enough to get him off work. (https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/denisovich/summary/)

The Funeral Party - Lyudmila Ulitskaya

August 1991. In a sweltering New York City apartment, a group of Russian émigrés gathers round the deathbed of an artist named Alik, a charismatic character beloved by them all, especially the women who take turns nursing him as he fades from this world. Their reminiscences of the dying man and of their lives in Russia are punctuated by debates and squabbles: Whom did Alik love most? Should he be baptized before he dies, as his alcoholic wife, Nina, desperately wishes, or be reconciled to the faith of his birth by a rabbi who happens to be on hand? And what will be the meaning for them of the Yeltsin putsch, which is happening across the world in their long-lost Moscow but also right before their eyes on CNN? This marvelous group of individuals inhabits the first novel by Ludmila Ulitskaya to be published in English, a book that was shortlisted for the Russian Booker Prize and has been praised wherever translated editions have appeared. Simultaneously funny and sad, lyrical in its Russian sorrow and devastatingly keen in its observation of character, The Funeral Party introduces to our shores a wonderful writer who captures, wryly and tenderly, our complex thoughts and emotions confronting life and death, love and loss, homeland and exile. (https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/837341.The_Funeral_Party)

Eugene Onegin - Alexander Pushkin

The main themes of the novel are poetry, literature, romance, passion, cynicism, and remorse. In contrasting Lensky’s hotheaded passion with Onegin’s cold cynicism, Pushkin shows the folly of both temperaments; while Lensky’s arguably unrequited, blind love for a woman leads him to his doom, Onegin’s cold aloofness causes him to miss an opportunity for romance which he will forever regret. Another core theme of the novel is the comparison between literature and real life; the poetic style in which the novel is narrated makes the reader share Tatyana’s suspicion that Onegin is not a real person but a tragic hero from one of his own novels. (https://www.supersummary.com/eugene-onegin/summary/)

Life and Fate - Vasily Grossman