#someone playing old hymns on the piano inside a chapel

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

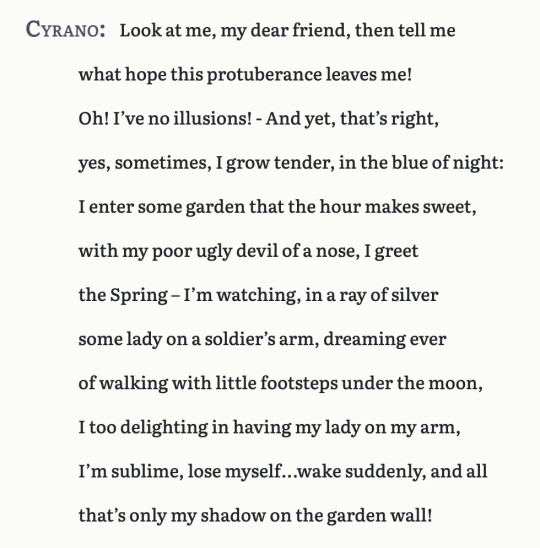

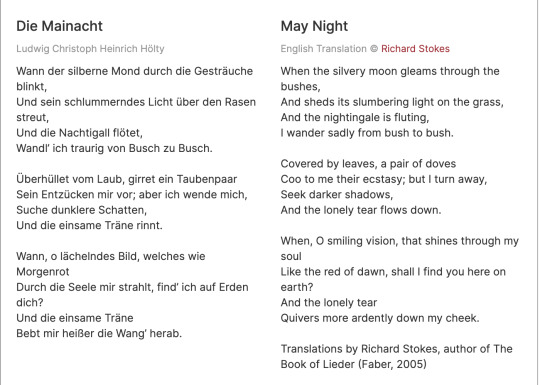

something about loneliness in the moonlight really gets me.

#same vibes from both.#i just envision cyrano spouting off the second poem (lyrics i should say) as he's watching christian kiss roxanne for the first time#and feeling his heart break#they would be the pair of doves in 'ecstasy' 👀#but i can just picture the despair and loneliness that each of these emotes#like#i can't really explain it#maybe cause i go on walks really late at night#when my phone's dead or turned off (not the best idea#i know)#and i just listen to the sounds of the world#a group of friends laughing#someone playing old hymns on the piano inside a chapel#the crickets chirping#idk it's just very beautiful#but also like. i'm reminded of my lack of someone to share it with#like i've never experienced having a romantic relationship where i could just. do that#and i've told myself for years that i “dont need one” but idk. i really want one#and i know that like... it'll happen whenever it happens or whatever but after a certain amount of time you start to get a little impatient#maybe it's just cause it's valentines day that i decided to be in the emotions today#meh#anyways#singleness awareness day and all#cyrano de bergerac#cyrano de bergerac kevin kline#cyrano de bergerac 1950#cyrano de bergerac original play#edmond rostand#die mainacht

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Angel In The Church

Content warning for gore, religious themes, and graphic violence to a child.

A man drives down the highway in an old sedan. He is running away from something. What it is, we do not know. Perhaps, we never will. He is speeding, dangerously above the limit, but there is nobody there to see it, not on this quiet road on this quiet morning. The light is soft, and almost beautiful, in the just-after-dawn, but he does not see it past the white of his knuckles cramped and clutching the steering wheel, and whatever he keeps looking over his shoulder hoping not to see.

He careens past the open-gated graveyards at the mouth of the road when he turns the corner onto the main street of a frosty little nowhere-town. He does not see her until it is too late. Her name is Celeste Leah Davidson. She is eight and three-quarters years old, and her favourite colour is lavender. Her mother did her hair this morning, and she likes her backpack because of the stars she glued on with her sister. She says they protect her from monsters by glowing in the dark. None of that matters when she is splayed backwards over the front of the car for a second, then under it, out of view. There is a scream held in the air like the last note of a song, suspended. There is a snap, then two dead-still thumps of the tires on the ground over her body, lying in the street.

It takes the man two tries to open the car door, his hands shaking, and he falls to the bloody asphalt, head cradled in his hands as though he cannot bear the light of day.

“Dear God, what have I done?! What have I done?!”

If he is begging for forgiveness- an answer- from the Lord, the Lord does not hear him.

Still, he is aware of whatever is behind him getting closer and closer- an unrelenting pursuer, the constancy of whatever happens after grief. He trembles as he picks up the body from the road, delicately at first, but then rushing as the panic sets in. There’s a quiet crunch from the body as it is shoved into the trunk, and if anyone was watching, they would see the man shudder.

When he is driving again, his knuckles are drenched in blood, and the stains seem to creep into his bones. He scrubs at them, but it never seems to go away.

Something makes the man keep driving, that night. Something just at the edge of his head, on the tip of the devil’s tongue, waiting for him when the adrenaline fades.

The night after that, when he pulls over to the side of the road to sleep, he thinks he hears something. He wakes up in the middle of the night to what he thinks is the girl’s scream repeated in the wind. He tries to rest as little as he can after that, and when the quiet encroaches, he turns up the radio, but all he can find is static. He turns it up all the way anyways, until he starts to hear a voice in that too.

It is the middle of the night, a month in, when he is falling asleep, and the car begins to shake in the middle of the night- thumps and screams from the back of the car. He shakes like a leaf in the wind, slamming his hands into his temples until the light of the radio goes black with his vision cutting out, hoping that it will kill him.

The next night, he dreams of blood- soaking the walls, pooling in the road, filling the earth like a biblical flood. When he wakes up screaming, delirious with exhaustion, he stares down at his hands while the lid of the trunk rattles. At the bloodstains that will not come clean, no matter how long he scrubs them raw in gas station bathrooms. With hands delicate and steady- hands with skill from another life, he pulls out a penknife. Methodically, steadily, he makes a slit along the back of his left hand, and slowly, slowly, pulls away the skin until the edges are turned inside out. If it hurts him, he does not show it- perhaps he is past the point where pain ends already. He stops when the blood loss makes him woozy, and starts again the next morning. For two days in the sedan parked in a field, the man skins his arms up to the elbows, until the only bloodstains are his own.

The next day, he stops at the edge of a town, and finds someone who will take the car for a bundle of cash. When he’s walked to the next one, his shoes are soaked with the water from blisters and blood. His eyes are sunken and hollow. The man who he buys a gun from at the edge of town thinks he might be half-dead already, and says nothing about the gloves of scabs stretching painfully bloody around his knuckles when he is handed the wad of cash.

He shoots himself in a flax field that night at sundown, and they do not find him until harvest that fall, when the combine spikes drive through his bones, picked at by crows in the field til they are bare. When the teenaged boy driving it steps down to look at what has happened, he sees the blue flax flowers growing from where his eyes once were, and the skin cracked dry and rotten-wet in equal measure. He throws up, and the image haunts him every time he closes his eyes for the next month, until they find him hanging in the barn from a rope tied to the rafters, an old wooden chair tipped over underneath him.

The car waits, empty in the used car lot at the edge of town. Two months later, a man walks in and buys it for his son’s birthday. The owner brings out the paperwork. He does not tell the man how he has not had a night’s rest since he bought it- about the dreams he has of blood and skin and knocking in the middle of the night. He does not tell the man about how he swears he sees it shake at night sometimes. He does not tell the man about the one with the scabbed hands and empty eyes who left it behind. Perhaps he does not know how to say it, or perhaps he wants the money, or perhaps he is made desperate by his visions- desperate enough to pass them on to somebody else. He breathes deeply through his mouth when he drives the car over to deliver it, and tries not to think about the plastic shopping bag of skin rotting in the compartment in front of the passenger’s seat, no matter how much he knows the scent will cling to his skin afterwards.

The boy’s name is Dylan, and he knows that his father doesn’t love him- knows that the car is made for him to open in front of his father’s friends, and nothing else- smells the heady, icy stench of rubbing alcohol on his father’s jacket and the sharp glint of eyeteeth in his father’s mouth when he hugs Dylan like he would never do without all eyes on him. Maybe that’s why the first thing Dylan opens is not the door of the car, but the trunk. Maybe he was looking for revenge, but what he finds is salvation instead.

The smell of months of shit and piss and rotting bedsores and the vomit from before the girl knew anything but this is still suffocating even after the trunk is opened, saturated into her skin and the fabric and the very essence of what she used to be. Her fingers were the first to go. “Delicate”, her mother had called them, once upon a time. “Artist’s hands”. She had lasted two days before sinking her teeth into her knuckles and lapping up the blood that swelled there, and another week before starting to rip into her fingertips with her canines. It has been night for so long. A long time ago, her mother told her she was named for the stars. She loved the stars. She does not remember the stars. She does not remember her mother. All she remembers is the infinite darkness, and the stench of her own decomposing and her broken bones healing curled up in the trunk, and the deep, animalistic pleasure of digging her teeth into meat and flesh still warm, still bloody, still breathing.

Her arms are a hollow framework all the way up to the elbows- like a man, lying as carrion in a field for the crows, with arms skinned up to the same spot. Her fingers, as delicately boned as before, are picked the cleanest- smooth white with bite marks across their surface. She had lost the beaded friendship ring from her best friend a day before the accident. The finger that it wrapped around is broken twice, once by the wheels of the car, and the second by her own teeth, sucking the marrow out.

As Dylan staggers back from the trunk, a whisper swoops across the crowd. “Godly,” they say. “Body and blood. A miracle.”

They lift her out gently, and snap all her bones when they splay her out from crumpled on the altar. The knife, good and sturdy from the basement kitchen, slices through the half-decomposed, abscessed skin above her shoulder blades, with the same firm hand as there must be the moment before you bring a chopping knife down on your fingers and slice all the way through bone. Pus leaks out, and the wings- made of white dove, stitched together alive and starved and dried, a frame of feathers- slip in. The meat hooks are pushed through the back of her arms, her collarbones, her sides, her thighs. Cleansed in fire, they brand her skin when they touch it, still hot. The flesh roasts. She has enough consciousness now, full on the communion, to know how to scream again. They hang her from the angled planks of the cathedral ceiling in the chapel, where the crucifix used to be.

A great joy in the parish is always best shared with the community. They hold a potluck in the chapel’s basement, and there is laughter and hymns and prayer. The widow’s son is a talent on the piano- he always plays in the balcony for services- and old Mrs. Hargreaves brings a pot roast from the recipe her mother always used. The girl who used to be named Celeste weeps above, scrabbling with skeletonized hands for a memory the scent rising from the basement brings up, of hiding behind her mother’s skirts, of playing tag on summer days, of dusty catechism books. She cannot remember, and for that she weeps more.

The wine always makes her head hazy, enough to slip away. They always give her a lot of it, to keep her from wailing during the sermons. Every year, for the first communions, they bring up the children to kneel in front of her. When her skin is pierced, they drink of the blood of heaven, and they all lie that it is as sweet as water. Her eyes watch the choir, as though she thinks she is already dead, but still her skeleton breathes, and her eyes blink glassily behind the curtained halo of her hair, tangled and matted with the ends still in the braids her mother carefully brushed out and tied so long ago.

They do not know her name from Before. If they did, they would not use it- would not care.

They call her Heaven now. Heaven Mercy Faith. The angel in the church on Crow’s-Elm Lane.

#horror#gore#gothic#religious#religon#catholic#catholicism#angels#death#creative writing#allusions to psychosis#suicide#corpses#car accidents#self cannibalism#cannibalism#cathedral#body horror#creative#my writing#writing#fiction#short story#angelcore#starcore#churchcore#cathedralcore

7 notes

·

View notes