#so much rage against this singular pond

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

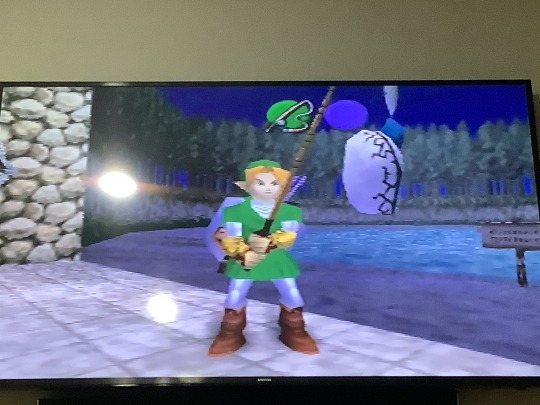

why did Nintendo have to make the fishing in oot so unnecessarily hard. at least on the n64 version- I MEAN- BRO I SPENT LIKE 3 DAYS TRYING TO GET THE GOLDEN SCALE MAN I JUST WANTED MY PIECE OF HEARTT 😭😭😭

THE AMOUNT OF TIME I SPENT IN THAT POND IS ASTRONOMICAL-

i spent over like 500+ rupees trying to get that big fish i am filled with rage.

also you can steal the fisher guy’s hat it’s hilarious. sorry the photo is kinda bad I was just taking a picture of my tv 😭

#oot#loz#legend zelda#Ocarina of time#rant#loz fishing#oot fishing pond#steal the hat#he’s like bald underneath it’s so funny#so much rage against this singular pond#i was so close to jumping through the screen and grabbing the guy by his shirt collar and aggressively shaking him#rambles from the ocean

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

No offense to Albert, and I cannot speak to the original context, but that is far too narrow and simplistic and even narcissistic a perspective, I’m afraid.

Everything that comes about—or “exists,” as it were—does so due to an indeterminably complex churning of interactions and relationships, a nonstop vortex of causes/effects, a single-field dynamic that ripples in all directions simultaneously, spatially and temporarily, and ceaselessly transforms within itself to unfold this singular, uninterrupted Now.

Think of the surface of a pond in the midst of a raging thunderstorm. That’s the level of incessant interaction we are speaking about. Do we really think a raindrop—even a sentient one—has that much influence?

Our actions, or inactions, though seemingly monumental at times from our own narrow little perspective, hold remarkably little sway over Reality, despite our terrified denials and desires for it be different. I know that goes against the whole “self-sufficient or self-determined person” concept, but any real investigation into our actual circumstances shows it to be the deeper Truth. While local influence is possible, striving for anything even remotely resembling “control” is a fool’s errand that leads to a lot of suffering.

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Untitled Goose Erotica

Part 1: Plowing the Groundskeeper

A ringing of a bell. A rustle of a bush. A light slapping and sloshing of a miniature wave as it moistens the dirt on the pond shore. A discordant honk.

The Goose emerges.

It leaves a gaping hole in the bush. With a shake, it releases the leaves which clung to it like forlorn lovers. Used and forgotten. Wasted and abandoned. Left to rot in the ground like so many treasures. The Goose does not have room in its heart for sentiment.

With a squat waddle, the Goose makes its way to the Pit, where it peers down, basking in its glory. Remembering its raison d’être, so beautifully encapsulated in a singular object. It would own them all. So it begins again the cycle of its dominance.

The Goose raises its wings for a moment, stretching above the Pit, then turns and waddles to the edge of the pond, stepping in with a knowing grace. The liquid is a soft caress against its rump, which floats effortlessly and refuses the wetness. Kicking its legs, the Goose propels itself over the depths of the pond. Depths that contain mysteries only the Goose knows. Not a thought crosses the mind of the Goose as it traverses the quaint body of water, not a thought save for the everlasting lust for absolute sexual supremacy.

Reaching the far shore, it steps aground and shakes. It peers from side to side, beady eyes taking in the scene: a picket fence dead ahead, closed to intruders; a pillar of memorial to its left; a picnic cloth to the right, basket left unattended.

The Groundskeeper opens the gate and carries out a radio. He places it against the fence and returns to his work on the far side, latching the gate shut behind him. The Goose approaches the radio and takes it in its beak. It feels the weight of the machine, heavy for its supple neck but light in comparison to the sins of the Goose. It was ready to sin again.

It laid the radio flat on the ground and stepped on the buttons, dancing with abandon atop the sorry machine. The radio blared to life, new wave music protruding from the speaker, filthying the air around it.

The Groundskeeper perks his ears, summoned by the sound of a genre he did not allow himself to listen to for ages. The genre that defined a relationship, a life. His world. His world for a long, long time. Now a distant memory, distant more in time, it felt, than in space; and he had made sure to create space. He wished sometimes, in the dark lonely nights of a snowy winter, or the empty summer afternoons, or the brisk and solemn fall mornings, or the bright spring days that still gave him hope year after year, he wished in all those times he used to hold his lover that they had parted on worse terms. It would be easier to rationalize. It would hurt less, knowing there was an irrevocable reason to leave. If only real damage had been done to them both! If only trust had been breached like the hull of their boat as they sailed the Mediterranean. If only he had let those empty summer afternoons keep him, let the meaning of those moments — now all too well realized in their absence — anchor him. He knew now what he’d feared: that he might be happy. That for once in his life he might have found a relationship as healthy and balanced as the Mediterranean, and one that made him feel as light. He was afraid he’d found himself, and who he found was far more than he believed he should be. So he left with neither a word nor a trace, treaded lightly across the dock in Cannes, and took a train far, far away. To be nothing more than a Groundskeeper in a small town where his importance would be limited, if noticed. Where there was no possibility of again accidentally becoming more than he should be.

The Goose could smell the Groundskeeper’s story, and the knowledge pleased it. Those that already thought lowly of themselves proved easiest to dominate. They would give in without hesitation, would willingly surrender to a punishment they believe they deserved. Perhaps, even, it would be deserved.

The Groundskeeper arrives at the gate as the Goose makes itself small by the hinges. The gate swings open and the Groundskeeper steps through, lumbering, weighed down with regret. He leans over to pick up the radio.

HONK

The Goose makes itself known, closing the gate behind the Groundskeeper.

HONK

The Goose grabs the Groundskeeper by the belt and drags him backwards. The strength of the Goose surprises the Groundskeeper, but he regains his footing and lurches forward. The Goose swings itself around him with the momentum, landing with wings spread.

HONK HONK HONK HONK

The Goose cries a cacophony and flaps its wings, summoning a rage the Groundskeeper had never seen paralleled. He cowers for a moment. The Goose strikes a deft a pluck at the belt of the Groundskeeper, snapping off the buckle. The two sides of leather strap hang limp against his thighs, and the waist of his pants sag down an inch. He swats at the Goose, but his arms move slow and the Goose ducks beneath, pecking again at the Groundskeeper, just below the belt line. The Goose can feel the girth of the Groundskeeper through two layers of cloth as its beak makes hard contact. The Groundskeeper doubles over. The Goose grabs the bottom of the crotch of the pants and backs away, pulling the Groundskeeper’s pants down around his ankles. The Groundskeeper begins to rise and chase the Goose but trips over his fallen trousers.

He is taken, for a moment, back to the Mediterranean, when he had been standing on the bow of their boat, his lover laying back, sunning on the deck. His lover had reached up and pulled his swim trunks down around his ankle, and had given him a push. He tripped over the trunks and splashed in absolute surprise into the water. When he came to the surface, his lover was laughing, and he could not help but burst into a fit of laughter himself. He pulled his trunks off his feet and threw them in a wad at his lover, a direct hit to the face, and they laughed harder, the Groundskeeper submerging as he forgot to tread water. He regained control of himself and watched as his lover undressed, then in a motion with as much fluidity as the sea itself, dove in.

The Goose takes the opportunity to round the back of the Groundskeeper and bites a hole through his underwear, exposing his anus: clean-shaven, as if he knew what was going to happen. The Goose breached the Groundskeeper’s tight hole and tongued inside him with abandon. The Groundskeeper sank further and further into his memory, too humiliated to face the horror of his reality.

He imagined it was his lover, who had swam under him, performing analingus in the salty sea. He felt his girth swell, and was in such throes of ecstasy he could not mind a single thought to how long his lover had been underwater for. He dared not even touch himself, his hands in their frantic circles keeping him afloat. His breath short and manic. He did not need to touch himself, the expert motions of his lover’s tongue did all the work. He felt hot semen pump through his girth and explode into the water, one more salty load lost in the sea. They only swam nude after that day.

The Goose feels the rhythmic contractions of the Groundskeeper’s prostate as he explodes a sadly small wad into his undergarments. The Goose hears, but takes no mind of, the Groundskeeper’s sobs. The Goose cares not why his victims wallow in misery; it cares only that they do. With its work finished — work because the Goose took no pleasure in these sexual acts, pleasure too small an emotion, no this work layered into a more complex fabric of being, a transcendence of mere sexuality — the Goose waddles around the side of the garden and enters through a hole in the shrubs. It plucks the single rose and hides it among the weeds. It sows nothing but chaos and fosters nothing but regret.

The Goose leaves the garden and finds its way into the alley.

1 note

·

View note

Text

He screamed. And that’s what ended up ending his life.

Belly down in the snowbank feeling the icy coldness seep in through her tattered canvas jacket Jean slows her breathing as she’d been trained to do. That wash of clarity settling over her like a blanket as she lines the sights of the rifle up with the unsuspecting deer’s honey brown eye. Beside her, though he says nothing, Maxamillion observes with clinical coldness. This is a test after all.

There’s a cough from the silenced rifle and a small flock of birds that had roosted in the trees near her snowbank take flight in alarm as the deer crumples into the snow. Behind it the trunk of the tree it had been standing next to is painted with gore. A clean shot right through the eye. Counting three more breaths before she stands the girl of 17 goes to clean her kill and field dress it.

Once again Maxamillion watches from just far enough away that Jean can still feel him lingering. Though perhaps that’s the wrong word. No, she can feel her father haunting the air that she breathes, making it heavy. For the past three years after Stephan had left her lying there in the snow, Jean had been the sole recipient of all of Maxamillion’s attention. She had all the scars to prove it. Along with one singular scratchy tattoo in the shape of an eye that covered a knob of scarred flesh that hid a small GPS tracker. A particular modification that had been made after Stephan had fled.

“Too bad I didn’t think to tag your brother. Though I don’t think you have it in you to actually hunt down and kill anyone do you, little bird? You were always the soft one.” His words came out with a sneer, punctuated with the slow hiss of his knife across the sharpening strap. Jean kept these words bottled inside of her chest knowing that one day they would be needed to fuel whatever rage it would take to finally kill the old man in his sleep.

What if all those words that he’d thrown at her just before the sharp sting of the belt buckle, or better yet the blade of his favorite knife, found her body were true? Plunging her field knife deep into the deer’s neck, feeling the hot sticky rush of blood over her hands brought Jean back into the moment. No. Her brain stated coldly. Those words were not true because if they were that means she was a failure and Maxamillion would have cut her throat and dumped her in the small pond on the property with the other’s long ago.

She would be laid with all the so-called ‘strays’ that he found on the property that he deemed were chasing them or spying on them for one vague reason or another. Most of them had been runaways. The other’s homeless that were just caught in the wrong hunting lands. Her father’s hunting lands.

Finishing the deer and slinging the long rifle against her chest Jean crouches and hefts the cleaned dressed corpse up across her shoulders, holding tight onto the two thick straps that were looped around the carcass. Work like this had made the young woman strong. Chopping wood, carrying kills, choking the life out of-

closing her eyes and taking an even breath Jean forces the look of horror on that one man’s face out of her mind. But he doesn’t leave.

He’d been a stray. Some run away that was from Vermont from what his ID had said. Only about 19 years old and on the verge of starving to death. It didn’t take much to kill him, and unlike the deer, she was accustomed to, he struggled. That’s what made the bile rise in her throat. Real honest to god fear and loathing of herself for stooping just as low as her father. But the kid had screamed. That’s what ended up ending his life is the scream and how Jean knew that the beating she would receive and the nights in the shed naked in the elements would be much worse than this.

Jackson had been the name on the ID. He had dark blue eyes set into a face that might have been handsome save for the deep circles and lips so chapped there was a little scab of blood in one corner of his mouth. Jackson had already looked like a corpse. Jean just took him that extra step.

Remembering the way her hands shook and how she had scrambled back away from the broken body of the boy she had just murdered Jean remembers the acid burn of her own vomit.

This hadn’t been the way Maxamillion had spoken of relishing a kill. This was awful, but the alternative would have been so much worse. Fingers aching as they roughly patted through Jackson’s pockets for anything useful she came up with his wallet and stared for a long time at the face of a boy that would have been very handsome if he had lived much past today.

The lie that she’d told her father that evening to why her hands and arms were scratched to hell was that she’d fallen through a dead bramble bush. Jean didn’t think he believed her, but those cold mismatched eyes did not ask any more questions. Instead, the young woman had been left with her own deeds. One thing Maxamillion had told her rang true. You never would forget your first kill. And still, there are times when Jackson visits her in the night, standing in some dark corner with one blood-filled eye and that look of abject slack-jawed horror on his skeletal face.

“You killed me.”

0 notes

Text

George Bancroft, The History of New Hampshire, 1842

Page 111: To the people of New Hampshire this peace gave a grateful respite. They were dispirited and reduced. The war had broken up their trade and husbandry, and weighed them down with a heavy burden of debt. The earth also was less fruitful than before; as if the kindly skies withheld their gifts at such an exhibition of the follies and cruelties of man. The governor was obliged to impress men to guard the outposts; and sometimes these were dismissed for want of provisions. In this situation, they applied to Massachusetts for assistance. Their application found that colony overwhelmed with witchcraft, and rent with feuds about the charter. Superstition and party spirit had usurped the place of reason, and the defense of themselves and their neighbors was neglected for the ghostly orgies of the witch-finder and the quarrels of the old and new chartists.

Page 138: The growing unpopularity of Shute admonished him, at this time, to return to England. Although the people of New Hampshire were quiet under his administration, yet there was rising in Massachusetts a violent and increasing opposition. Having been a solider in his youth, and accustomed to military command and obedience, he was poorly prepared to brook the crosses and perplexities of political life. He did not possess that evenness of temper and calmness, which are so necessary for the management of difficult affairs. It was in the midst of an Indian war, when difficulties surrounded the government, that he left for England, and Lieutenant Governor Wentworth succeeded to the chair. It was resolved to prosecute the war vigorously. Wentworth, in the absence of Shute, took the field as commander-in-chief, and displayed the prudence and energy of an able leader. He was careful to supply the garrisons with stores and to visit them in person, to see that the duties of all were strictly performed.

Page 146: The battle of Lovewell’s pond was the most obstinate and destructive encounter in the war. Commissioners were now despatched, on the part of New England, to Vaudruil, governor of Canada, to complain of the countenance he had given to the Indians. This procured the ransom of some captives, and exerted an influence favorable to peace. After a few months, a treaty was ratified at Falmouth. Never were the people of New Hampshire so well trained to war as at this period. Ranging parties constantly traversed the woods, as far north as the White Mountains. Every man of forty years had seen twenty years of war. They had been taught to handle arms from the cradle, and, by long practice, had become expert marksmen. They were hardy and intrepid, and knew the lurking places of the foe. Accustomed to fatigue and familiar with danger, they bore with composure the greatest privations, and surmounted with alacrity the most formidable difficulties.

Page 230: Everything indicated that the people of New Hampshire were fast uniting with the views of Massachusetts and the other colonies. In vain did the governor labor to prevent the free action of the people. In vain did he dissolve and adjourn their meetings. In vain did he declare them illegal. The rose when he entered among them to declare their proceedings void; but no sooner had he retired than they resumed their seats and proceeded, unrestricted by forms. An authority was rising in the province above the authority of the governor—an authority founded on the broad basis of the people’s will—an authority before which the shadow of royal government was destined to pass away. The people appointed committees of correspondence, and chose delegates to the provincial congress at Philadelphia; and nowhere were the proceedings of the congress more universally approved. “Our atmosphere threatens a hurricane,” wrote the governor to a confidential friend. “I have strove in vain, almost to death, to prevent it. If I can, at last, bring out of it safety to my country, and honor to our sovereign, my labors will be joyful.”

Page 231: The people of New Hampshire soon gave an example of the spirit by which the whole country was animated equally with themselves. An order had been passed by the king in council prohibiting the exportation of gunpowder to America. A copy of it was brought by express to Portsmouth, at a time when a ship of war was daily expected from Boston to take possession of fort William and Mary. The committee of the town, with secrecy and despatch, collected a company from Portsmouth and some of the neighboring towns, and, before the governor had any suspicion of their intentions, they proceeded to Newcastle and assaulted the fort before the troops had arrived. The captain and five men, who were the whole of the garrison, were taken into custody, and one hundred barrels of powder were carried off. The next day another company removed fifteen of the lighter cannon, together with all the small arms and other warlike stores. These were carefully secreted in the several towns, under the care of the committees, and afterwards did effectual service at Bunker’s Hill. Major John Sullivan and John Langdon were the leaders in this expedition. No sooner was it accomplished, than the Scarborough frigate and sloop of war Canseau arrived, with several companies of soldiers. They took possession of the fort, but found only the heavy cannon. Sullivan and Langdon were afterwards chosen delegates to the next general congress, to be holden on the tenth of May.

Page 247: While such was the enthusiasm for liberty, it was but natural that a violent resentment should be kindled against those who still adhered to the royal cause. These took the name of tories; their opponents, the name of whigs, or sons of liberty. The tories were persecuted with relentless fury. Some of them were arrested and imprisoned. Some fled to Nova Scotia, or to England, some joined the British army in Boston. Others were restricted to certain limits, and their motions continually watched. The passions of jealousy, hatred and revenge were under no restraint. Although many lamented these excesses, there seemed to be no effectual remedy. All the bands of ancient authority were broken. The courts were shut; the sword of magistracy was sheathed. But amidst the general laxity in the forms of government, order prevailed; reputation, life and property were still secure; thus proving that it is not in outward forms of austerity, or sanguinary punishments, or nicely written codes, or veneration for what is old, that our rights find protection—but in the potent, though unseen, influence of family ties, virtuous habits and lofty example. These contributed more, at this time, to maintain order than any other authority; thus illustrating how much stronger are the secret than the apparent bonds of society. But the people of New Hampshire proceeded to perfect, as far as possible, their provisional government. The convention which had assembled at Exeter, was elected but for six months. Previous to their dissolution in November, they made provisions, pursuant to the recommendations of congress, for calling a new convention, which should be a more full representation of the people. They sent copies of these provisions to the several towns, and dissolved. The elections were forthwith held. The new convention promptly assembled, and drew up a temporary form of government.

Page 291: The legislation of this, as well as a few preceding and subsequent years, evinces at once great economy in the legislature and great financial distress among the people. In 1791, the salary of the governor was fixed at two hundred pounds, of the chief justice at one hundred and seventy pounds, and the secretary of state at fifty pounds per annum. Laws, granting relief to towns—directing the treasurer not to issue extents for outstanding taxes—providing for the receipt of specie in payment of public dues, at the rate of one pound for two in state notes—granting reviews and staying ,for a limited time, all proceedings against bondsmen, were of frequent occurrence, and indicated, in characters not to be mistaken, the severity of those financial embarrassments, which the expenses of the war had imposed upon the people of New Hampshire, and which neither the unrivaled industry nor the reviving enterprise of its citizens had yet been able to remove.

Page 294: In conclusion, they solemnly “remonstrated against the said act, so far as it relates to the assumption of the state debts,” and requested that, “if the assumption must be carried into effect, New Hampshire might be placed on an equal footing with other states.” Opposed as they then were in their political attachments, it is a singular circumstance, that, at this early period, Virginia and New Hampshire occupied the same ground upon this important question. Though generally belonging in name to that federal party, which was by many deemed to favor a concentration of all political power in the general government, the people of New Hampshire showed, on more occasions than one, a firm attachment to democratic principles, and a patriotic zeal for their rights as citizens of a sovereign state.

Page 362: The people of New Hampshire contributed no less to the success of the war than they did to its commencement. Its hardy citizens were to be found in every hard-fought field. Its seaboard contributed its weather-beaten seamen to man our navy, and sent whole companies to mingle in the conflict which raged on our frontiers. Recruits swarmed to the seat of war from every part of the state. Every village furnished its squad. Every scattered settlement among the mountains contributed its man. In some instances whole families came forward at the call of their country; and father and son left their little homestead in the wilderness and marched to the post of danger together. Had these brave men remained quietly by their own firesides, and left to others the noble task of defending their country, far different would have been the result of the elections at home; and far different, too, there is reason to believe, the result of some of those fierce conflicts on the frontier, in which the American flag floated in triumph over body fields and vanquished enemies.

Page 425: While such was the state of things at home, the people of New Hampshire had seen a revolution progressing in Connecticut, similar to that which was now beginning among themselves. Ever since the first settlement of Connecticut, the people had groaned under an oppressive system of religious intolerance. It was a complete and most odious union of church and state. None but the standing order of clergy could there obtain a legal support; and the laws for the support of that order were such a direct violation of the right of every man to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, that by many they were deemed “disgraceful to humanity.” Often was the parish collector seen robbing the humble dwelling of honest poverty of its table, chairs and andirons, or selling at vendue the cow of the poor laborer, on which the subsistence of his family depended, in order to load with luxuries the table of an indolent priest, or clothe in purple those who partook with him of the spoils of the poor. All ministers of the standing order were viewed as thieves and robbers—as wolves in sheep’s clothing—who had gained a dishonest entrance into the fold, and whom it was the duty of the standing order to drive out.

Page 426: In 1818, a bill was reported to the convention of that state, confirming freedom of conscience to all. Every man possessed of real independence and enlightened views, rejoiced at a revolution which sundered so monstrous a union of the church and the state in Connecticut. The clergy of the standing order deprecated—mourned—threatened, and exclaimed, “Alas! for that great city!” But the vast concourse of the people joined in thanksgiving for its destruction. Such was the change which the people of New Hampshire had witnessed in a neighboring state. They themselves were bound by a system less odious in the degree of practical evil which it inflicted, but in principle essentially the same. The act of the 13th of Anne, empowered towns to hire and settle ministers, and to pay them a stipulated salary from the town taxes. This was not directly a union of church and state; but it operated most oppressively. Each town could select a minister of a particular persuasion, and every citizen was compelled to contribute toward the support of the clergyman and to build the church, unless he could prove that he belonged to a different persuasion and regularly attended public worship elsewhere on the Lord’s day.

0 notes