#so like aliens didn’t even attack us during the age of strife. it was all Jimmy Space.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I’ve got a pretty solid theory on the Emperor, and it’s that he was literally just some guy, until he wasn’t. Sure, he was a Perpetual, but he wasn’t really anything interesting until someone gave him the idea to unite humanity under his manner during the late Age of Technology.

And we’ve all been suffering ever since then.

#warhammer 40000#god emperor of mankind#I of course mean to imply he led the MoI uprisings#trying to give humanity a Them to be terrified of#and then when that didn’t work he false-flagged as countless xenos raiders#so like aliens didn’t even attack us during the age of strife. it was all Jimmy Space.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Icarus cursed and gripped his restraint harness tighter as the Thunderhawk shuddered like a child’s rattle toy. “Damn it Hirvik, can you keep from giving us all head trauma?” The response crackled over the vox in the former Space Wolf’s irritatingly cheerful voice. “You wanna come up here and fly through a war zone? How about you stick to stealing and leave the flying to the genius!” Icarus cut the link as Hirvik launched into another rowdy song of his homeworld and imagined how good it would feel to strangle his battle brother. Then the gunship shook again and he tried not to think of the void battle occurring around them. His beloved strike cruiser *Night Hunger* had plowed into the orbit of the unnamed demon world alongside the *Soul Eater* and *Final Dance*, tearing down orbital platforms with concentrated Lance strikes. The resident fleet has scrambled to meet them, erupting in a orchestra of fire and steel in the void. The fleet didn’t matter, in the end it wan’t the true target. This world has an artificial moon, an orbital fortress constructed by the Dark Mechanicus for one who called himself The Apostle of Bliss. Once a warrior of the Emperor’s Children and avid follower of the Prince of Pleasure, he’d built a fierce reputation as a Warband leader and duelist. This raid had been specially planned to target the Apostle and take from his collection something of special interest. No great assault force here but rather a targeted strike by a select small team. That was how he’d found himself here in the belly of a gunship flown by a Fenrisian madman. Alongside him were the rest of the selected, strapped in and ready for battle. Hulking Drogan snarling as the demon within shifted his flesh to the war form, steadfast Talorax in his indomitable terminator suit, ever confidant Vico tending final rites to his power sword, and silent Moloch holding his ever present bolter. Hirvik crackled back to life through the link, “Everybody brace yourselves!”

To be fair, it was only Hirvik’s skills as a pilot that saw them get through it. He guided the gunship at high speed through the hail of defensive fire, past the void shields as they momentarily overloaded, and slipped into one of the still open docking bay. He pulled the throttle hard, firing afterburners in an attempt to slow down even as he twisted into a skidding 180. The wing mounted bolsters spat death, chewing up anything in their sight line. The Thunderbird finally ground to a halt and the restraint harnesses sprang open as the the boarding ramp hissed open. Drogan and Talorax were out first, charging into the wave of gunfire that greeted them. Icarus and Moloch thundered out after them with Vico close on their heels. A swarm of foes came crawling out to defend the ship of their masters, cultists wielding auto guns and las-weapons alongside gun servitors hauling heavy stubbers. Numbers meant nothing before the Space Marines though. Talorax storm bolter roared, shredding heavy weapon servitors as Icarus and Moloch picked off any attempt at flankers. Drogan and Vico tore a path through with demonically enhanced strength and energy shrouded blade. Nothing could stand before their might. When the carnage settled the group divided. Drogan and Moloch dug in to guard their escape craft with Hirvik while Talorax, Icarus, and Vico moved on the target.

The deeper they went into the fortress the less resistance they met. It was fact that unnerved Icarus, even more so that they had met no Astartes resistance. When the last bulkhead slid open he knew why. The chamber they entered was large and circular, lit with bright overhead lumens. Rich gold veined white marble clicked underfoot, an awful terrible racket blasting from hidden vox speakers, an overpowering mix of so many sweet perfumes and foul odors assaulted the senses. The walls were truly amazing, lined with rack upon rack of weapons. Icarus saw mauls, blades, spears, hammers, daggers, all manner of melee weapons. He saw weapons of Imperial craft, chaos icons, everything xenos from an Orc choppa to Necron warscythe. It was a collection that might even rival the Vault’s own armory. As the three warriors spread out, a single opponent awaited them. Etiad Colos, the Apostle of Bliss, greeted his intruders with a broad smile and theatrical bow. He might have been handsome once, before his fine patrician features had been ruined by serpentine tattoos, heavily caked colorful powders, and a forest of steel piercing exposed flesh. His white hair was left in long plaits down his back, each movement causing them to jangle raucously with interwoven bells and chimes. His power armor was a riot of bright, garish, conflicting colors that might drive a mortal man insane. His voice was fluent and smooth, seemingly unaltered unlike the rest of him. “Ah welcome friends. I hope you don’t mind but I sent my brothers away. The Dark Prince foretold me of your arrival and I wanted to be a gracious host. Would you perhaps like some refreshment? I am sure there are delights here your goddess could never let you experience.” The silence that followed was filled with only the rasp of drawn steel. Vico leveled his sword in a duelist’s stance, Talorax revved his chainaxe, and Icarus drew his short bladed combat knife. Etiad grinned at them through teeth filed down to points. Laughing, he strode over to the wall and selected a blade. “Do you know what this is? This a Charnabal Sabre forged upon Terra during the age of strife, gifted to me by the Phoenician himself. You should be honored that such a weapon shall take your lives.” With a shout he leapt forward and battle was joined.

They were losing, badly. Icarus has known excellent swordsmen, fought plenty of them, but he’d never encountered anything like this. Etiad moved with a level of speed and grace he could only compare to the filthy Eldar, his attacks so fluid it looked more like a dance. He weaved around blows or slid them off his blade only to strike back viper fast and draw blood. He dodged a blow from Talorax that would have bisected him, twirling around to slice at the vulnerable joints on the back of the terminator legs sending the Iron Warrior to his knees. Icarus leapt in then, attempting to drive his knife up through the rips, only to have it torn from his grip. He jerked his head back as fast as he could and grunted in pain as the blade sliced deeply across he cheek rather than through his eye. A split second later a fist crashed into his jaw with a painful crack of teeth. He stumbled away as steel crashed against steel once again, Vico darting in to take the lead. The Blood Angel was the greatest swordsman in the Eternal Vaults and Icarus has never seen him so hard pressed, every iota of focus harnessed just on the defensive. All the while Etiad was laughing and singing, crying out for them to do more, try harder, it was enraging. He needed a new weapon and scanned the many mounted around the chamber. His gaze fell upon a long bladed polearm, a glaive he’d seen wielded by the pain loving breed of Eldar xenos. Spitting a mouthful blood Icarus snatched the glaive, the weapon feeling good in his hands if a bit light. Talorax was back on his feet and Vico had pulled out, a fresh cut on his face already healing. They all shared quick glances, each knowing they had to end this soon.

Etiad came at them again, laughing with mad joy. But this time they were ready. The charnabal sabre crashed down onto Vick’s waiting blade. But before the Appstle of Bliss could twirl away Icarus came in from the side, smashing the foe in the face with the butt of the glaive. Etiad stumbled right into the waiting bulk of Talorax. The mighty terminator gripped his wrists in a crushing grip and pulled. Etiad screamed in agonized ecstasy as flesh tore and ceramite cracked. He screamed anew as Icarus drove the glaive through his spine, the crackling blade bursting from gaudy chest plate. The Apostle of Bliss gave them a ruined smile, his last words choked through a mouthful of blood. “So..... exquisite.....”. Then Vico’s crackling sword descended and his head rolled free.

Icarus waited only the deep forged of the Eternal Vaults, watching Talorax at work. The Iron Warrior pulled the shaft of white hot metal from the forge and thrust it into the waiting water bucket, cooling in a hissing cloud of steam. He withdrew it, inspected his work, and with a nod of approval handed it to Icarus. The Archite Glaive has been reforged, made more suitable for an Astartes with more heft and weight. The blade was a shimmering thing, the alien metal mixed with the fragments of his old power sword. The Eternal hefted his new weapon and grinned. It felt good.

@fuukonomiko @just-another-warsmith @askvicothefallenbloodangel

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sound of Fury

“America, as a social and political organization, is committed to a cheerful view of life,” Robert Warshow wrote in his seminal 1948 essay “The Gangster as Tragic Hero.” Democracies depend on the conviction that they are making life better and happier for their citizens; only feudal and monarchical societies can enjoy the luxury of fatalism or a fundamentally pessimistic view of life. Praising the gangster genre as a form of modern tragedy, Warshow also accounts for film noir in his statement that, “There always exists a current of opposition, seeking to express by whatever means are available to it that sense of desperation and inevitable failure which optimism itself helps to create.” The gangster’s demise is the purest American tragedy because it is driven by his mania to climb the ladder of success. The end of his saga is inevitable, so in chasing success he is really chasing failure; his self-destructiveness expresses defiance at the inevitability of defeat, but also confirms it.

This underground river of pessimism and disillusionment unites the pre-Code films of the early thirties and postwar film noir; they share a tone of bitter gallows humor; a satisfaction in being wised-up, knowing the score; they flaunt the scars and calluses of lost innocence. Pre-Code movies reflected the free-fall of the Depression, the farce of Prohibition and the dizziness of a society edging towards anarchy. Noir exposed the suppressed anguish of WWII, the anxiety of the Cold War, the stresses of conformity and materialism.

Films like Cry Danger (1951)—recently restored to full glory by the Film Noir Foundation—depict a battered, abraded country that has turned cynicism into a running gag. A man just out of prison after serving five years for something he didn’t do trades sour wisecracks with a one-legged, alcoholic ex-Marine. They make their home in a dilapidated trailer in a scruffy park perched on Bunker Hill, where the proprietor sits around strumming a ukulele and ignoring the busted showers. The vet (Richard Erdman) falls for a pickpocket who steals his wallet whenever he gets drunk. The ex-con (Dick Powell) idealistically tries to vindicate his best friend, who’s still in jail, only to find out he’s a double-crossing liar. The film achieves an extraordinary blend of the glum and the snappy, a deadpan insolence that saturates the air like smog. “What’s five years?” Powell says of his stretch. “You could do that just waiting around.”

While pre-Code movies gleefully portrayed an “age of chiselry,” a country where everyone was looking for an angle, they never plumbed the depths of alienation, fatalism and misanthropy that noir opened up. For all their knowing skepticism, Depression-era films evoke a sense of camaraderie, a shared body heat from people huddled and jostling together—maybe cheating each other, but still sharing jokes and boxcars, Murphy beds and stolen hot-dogs. Noir, by contrast, purveys a chilling sense of isolation and social atomization; not only institutions but individual relationships are corrupt and predatory. There’s no longer a hard-times sense of being all in the same boat. As Kirk Douglas nastily smirks at his colleagues in Ace in the Hole: “I’m in the boat. You’re in the water.”

Noir used unpretentious, low-budget crime thrillers to smuggle this caustic vision into movie theaters during a time when, on the surface, America was at the height of prosperity and social cohesion. Unlike the early-thirties gangster cycle, which reflected a real wave of lawlessness, the crime movies of the fifties were made during a time when the murder rate was lower than in previous or succeeding decades, perhaps as a channel for other, submerged anxieties. Noir’s prophetic vision of disintegrating communities has become only more compelling with time, a development that may explain the passionate revival of interest in film noir in the last decades of the twentieth century.

Healthy, functioning groups don’t exist in noir; even gangs and criminal “organizations” fall apart because their members are out for themselves, ready to betray each other for a payoff or a bigger share of the take. Institutions like politics and business appear only in stories revealing their corruption. The police are the only representatives of government commonly seen, and they are often bullying and crooked, hounding innocent suspects with sadistic relish. Even films that take the side of law enforcement underline hostility between cops and the people they protect. Apart from the justice system, the public sphere does not exist: the town meetings and popular movements that crowd the screen in thirties films, with indignant and excitable citizens marching, rioting or celebrating, are unimaginable in film noir. People seem to exist in a vacuum.

In part, this vision reflects the privatization of life that accelerated in the postwar era, as cars replaced trains; television replaced movie theaters; appliances eliminated the need for servants, milkmen and ice men; suburban back yards took the place of parks, all part of the glorification of the detached home for the “nuclear” family. The homogeneity of the suburbs and the intrusiveness of media and advertising paradoxically diminished any sense of place or community. Meanwhile, Cold War paranoia meant that expressions of communitarian spirit or calls for collective action could rouse suspicions of communist sympathies.

Many of the writers, directors and actors associated with film noir were liberals, often former Communist Party members who had seen the left-wing idealism of the thirties buried by World War II and then vilified during the Cold War. Disillusioned, they used crime movies to indict a culture of rampant greed and cut-throat competition. Thieves’ Highway(1949), the last film directed by Jules Dassin before he left the country to escape the blacklist, slices open the produce business to reveal the rotten heart of capitalism. Even something as pure and nourishing as an apple becomes a poisoned agent of strife when it’s equated with money. A Polish farmer, enraged at being paid less than he was promised for his apples, flings boxes of them off a truck, screaming, “Seventy-five cents! Seventy-five cents!” The apples roll wastefully across the ground, an image foreshadowing the film’s most famous shot, when after the same truck has careened off the road and exploded, apples roll silently down the hillside toward the flaming wreck. When the dead trucker’s partner finds out that money-grubbers have gone out to collect the scattered load to sell, he begins kicking over crates of apples, fuming, “Four bits a box! Four bits a box!” Everyone in the movie is “just trying to make a buck,” and cash haunts the film, dirty crumpled bills changing hands in a series of soiled, coercive transactions.

It is easy to see why the House Un-American Activities Committee wanted to drive people like Dassin out of Hollywood. Films such as Joseph Losey’s The Prowler (another Film Noir Foundation restoration) and Cy Endfield’s The Sound of Fury, (a.k.a Try and Get Me! 1950, the FNF’s next project) are scathing attacks on a materialistic society, unmasking the American dream as a shallow and shabby illusion that breeds crime and shreds the social fabric. (Both directors fled to England in the early fifties to avoid persecution by HUAC.)

Endfield’s stark anti-lynching drama opens with a down-on-his-luck family man hitch-hiking on a dark highway; he tells the trucker who picks him up that he’s been looking in vain for a job. Howard Tyler (Frank Lovejoy) moved his wife and son out to the postwar California suburb of Santa Sierra, hoping for a better life; “I can’t help it if a million other guys had the same idea,” he complains bitterly. They live in a shabby little bungalow behind a wire fence that makes the place look like a miniature P.O.W. camp. Howard’s pregnant wife hates the idea of using a charity clinic, and frets over money owed for groceries, while his whiny little boy begs for money to go the baseball game (“All the other kids are goin’!”) A bartender at a bowling alley sneers at his cheap customer: “You take a beer drinker, you got a jerk.” If Howard weren’t so dejected and humiliated, he would never fall under the spell of Jerry (Lloyd Bridges), the vain braggart he meets at the bowling alley.

Primping and preening, flexing his muscles and showing off his fancy aftershave (“Smells expensive!”), the manic Jerry boasts about his sexual conquests and the big money he makes, and he treats the modest, submissive Howard like his valet. He offers to put him onto something good—“nothing risky”—just driving the car for his hold-ups. When Howard hesitates, Jerry snorts, “You guys kill me! The more you get kicked in the teeth the better you like it.” Their first job is knocking over the grocery store at a cheap motel (“The Rambler’s Rest”), where Jerry easily intimidates an elderly couple and pistol-whips their son. Intoxicated with the easy money—and a few stiff drinks—Howard bursts in on his family with armfuls of groceries. His wife gasps at the extravagance of baked ham and canned peaches, and he brags that now they can get their own TV, and won’t have to go over and watch their neighbors’. “And we’ll throw this piece of junk away!” he crows, pointing to the family’s radio. Soon Howard is buying his wife new shoes and dresses with hot money, telling her he has a night job at a cannery. His little boy sports a cowboy outfit and ambushes his jumpy father with toy guns.

Unsatisfied with these penny-ante crimes, Jerry comes up with a scheme to kidnap a wealthy young man and hold him for ransom. He’s overcome by envy as he fingers the victim’s suit, tailor-made in New York, and after they’ve taken him out to a gravel pit in a disused army base, Jerry panics and kills him. When Howard gets home, dazed with horror and guilt, his wife wakes and tells him about the lovely dream she was having: she had the baby and this time there was no pain at all; “I got right up out of the hospital and took her shopping. I was buying her a pinafore.” Even in her dreams she’s a consumer, subconsciously linking commercial goods with the fantasy of a painless life.

As Howard mentally unravels, the shoddy vulgarity of the culture around him takes on a sinister cast. Jerry shows him the ransom note he’s written in a diner while ordering a steak sandwich (“Cow on a slab!” the waitress yells.) For cover, they go out of town to mail the letter, taking along Jerry’s girlfriend, a glossy blonde, and a lonely manicurist she has dug up for Howard. In a nightclub, he’s subjected to a string of dumb jokes and parlor magic tricks from a burlesque comedian. “Blame my psychiatrist,” the comic quips, “I didn’t pay my bill last month and he’s letting me go crazy.”

From its opening moments, the film depicts the crowd as a mindless and malevolent force, which will eventually be stirred to frenzy by sensationalizing newspaper articles. Crowds in noir are always bloodthirsty mobs, surrounding and destroying strangers in their midst; the communal desire for security is tainted by bigotry and ignorance. This is a dark inversion of Capra’s rallying citizens, or even the all-for-one armies of bums who fight for their squatters’ rights in Wild Boys of the Road. Movies of the Depression era never saw anything wrong with wanting money, good food, a pair of shoes, or even fur coats and diamond bracelets. They are tolerant of people—especially women—who do whatever they have to do get ahead. By contrast, The Sound of Fury shows materialism—the desire to keep up with the neighbors, to make a better life for your family—as a force that corrodes souls and breaks down social decency. The deepest well of pessimism in noir is a distrust of change, desire and ambition. “I just want to be somebody,” people are always saying, but the urge to squeeze more out of life, to grab a chance at happiness, is brutally punished.

Below the surface, the force driving noir stories is the urge to escape: from the past, from the law, from the ordinary, from poverty, from constricting relationships, from the limitations of the self. Noir found its fullest expression in America because the American psyche harbors a passion for independence, an impulse to be, in the words of Walt Whitman, “loosed of limits, and imaginary lines, / Going where I list, my own master, total and absolute.” With this desire for autonomy comes a corresponding fear of loneliness and exile. The more we crave success, the more we dread failure; the more we crave freedom, the more we dread confinement. This is the shadow that spawns all of noir’s shadows: the anxiety imposed by living in a country that elevates opportunity above security; one that instills a compulsion to “make it big,” but offers little sympathy to those who fall short. Film noir is about people who break the rules, pursuing their own interests outside the boundaries of decent society, and about how they are destroyed by society—or by themselves.

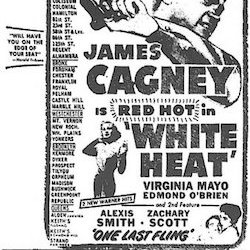

The gangster, Robert Warshow wrote, is driven by the need to separate himself from the crowd, but in doing so he isolates and dooms himself. White Heat (1949), which brought James Cagney back to the gangster persona that made him a star, came out one year after the publication of “The Gangster as Tragic Hero.” It took the “man of the city” (as Warshow defined the gangster) out of the city, but Cagney’s explosive death atop an industrial gas tank is the supreme illustration of Warshow’s observation that the gangster’s pursuit of success—“Made it, Ma! Top of the world!”—is a pursuit of death.

White Heat is also a perfect example of what Edward Dimendberg (in Film Noir and the Spaces of Modernity) called “centrifugal” noir: it’s a film without a center, about a world flying apart like the cooling fragments of an exploded star. Cagney’s gang, decaying under the strains of resentment, betrayal and madness, moves between equally bleak urban and rural hideouts. After robbing a train in a rocky no-man’s-land, they hole up in a frigid, creaky old farmhouse “a hundred miles from nowhere,” as Cagney’s wife gripes. Cooped up together in this gloomy Gothic house, surrounded by split-rail fences and naked, rolling hills, they snipe at each other and grumble about their leader. Cody Jarrett (James Cagney) suffers debilitating migraine headaches and huddles in the lap of his gaunt, fiercely loyal Ma. The realization that came to Cagney in Public Enemy as he stumbled into the gutter in the rain—“I ain’t so tough”—is here amplified into an infantile weakness, perpetually on the verge of breakdown. Cody’s frailty only makes him more vicious. At his orders the gang leaves a wounded member behind, bandaged and in pain, to freeze to death once they make their move to a motor court in LA. The motel is typical of the “non-places” (in Marc Augé’s term) where noir flourishes: marginal, transient spaces where “people are always, and never, at home.”

The banality of the modern west makes room for Cagney’s majestically psychotic performance, fine-tuned and sensitive as a landmine. Cody Jarrett crumples inward under the crushing pain and then erupts, and White Heat similarly closes in and then shatters people are either cramped in suffocating enclosures (Cody shoots a man while he’s locked in the trunk of a car, cruelly offering to “give him some air”), or stranded in vacant, inhospitable spaces. At the rural hideout, the wind is always blowing bitterly around the house, tossing the trees; Cody walks alone at night, talking to his dead mother, who was shot in the back by his wife while he was in jail. He tells a friend—really a police plant who will betray him—how lonesome he is, because “all I ever had was Ma,” and how hard his mother’s life was, “always on the run, always on the move.” White Heat brings together the ultra-modern—radio tracking devices; drive-in movie theaters—with the pre-modern, even the primitive. It proves not just that film noir can thrive in the country as well as the city, but that noir was not merely a response to the new—industrialization, the bomb, etc.—but drew on deep veins in the American psyche and the American landscape: the desire to stand alone on top of the hill, even if there’s nowhere to go from there but death; and an accompanying fear of being buried “on the lone prairie,” having no one to talk to but the night wind.

by Imogen Sara Smith

#Imogen Sara Smith#The Chiseler#The Sound of Fury#James Cagney#White Heat#Raul Walsh#Noir#In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the Cit#Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy#the criterion collection

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Post has been published on Otaku Dome | The Latest News In Anime, Manga, Gaming, And More

New Post has been published on https://otakudome.com/reviews/final-fantasy-vii-remake-review/

Final Fantasy VII Remake Review

Final Fantasy returns with a newish entry into the storied franchise this time with a “from the grounds up” remake/reboot of classic RPG Final Fantasy 7. Like the original the game follows former soldier turned mercenary for hire Cloud Strife as he’s tasked with a job in aiding with the destruction of the evil Shinra corporation who’s using Earth’s energy or Mako for its own financial gain. While most of the game covers the original’s storyline it makes some key changes that will change the Final Fantasy 7 story and perhaps even the Final Fantasy universe as we currently know it.

Final Fantasy VII Remake is a 2020 remake and reboot of the original Final Fantasy VII from 1997. It is developed and published by Square Enix and is currently available as a timed exclusive on Playstation 4.

Editor’s Note: Near complete to complete spoilers for Final Fantasy VII Remake may be present within this review. Some spoilers for the 1997 original may be present for comparison’s sake with the new storyline. This review is done from the perspective of a first time playthrough experience of Final Fantasy VII as a whole.

A legendary RPG returns for the modern age in Final Fantasy VII Remake.

When Square Enix showed off what looked to be a revamped version of Final Fantasy VII merely to excite gamers with the possibilities of their then-new, in-house Crystal Engine for the Playstation 3 I can’t imagine they’d have thought excitement for the prospect would blow up into an actual retail project being developed. Now here we are a decade and a half later and the remake has been fully realized in retail stores and on gamer’s consoles. It’s perhaps the start of a new beginning for Cloud Strife and his friends as they take on the ever changing winds of destiny.

Revisit Final Fantasy VII in a new coat of paint.

THE GOOD: Final Fantasy VII starts just as the original game did with eco-terrorists Biggs, Wedge, Jessie, Barrett, and recently hired mercenary Cloud Strife invading a Shinra reactor. While the group move throughout the reactor they have Cloud do most of the fighting. This eventually leads to Cloud and Avalanche leader Barrett teaming up to do battle against a giant machine after setting off a bomb. Though they barely manage to escape the group begins to question themselves after witnessing the the destruction of their attack. Set on their resolve the group continue forward with their plans to eliminate Shinra to protect Earth and the Mako energy it provides along with Tifa, Aerith (whom Cloud encountered following the bombing), and Red XIII who joins the group after they invade a lab finding he was an experiment by Shinra scientist Hojo. As the story progresses Cloud begins to suffer from visions of Sephiroth; a soldier who became a legend during his and Zack Fair’s early military career. Meanwhile Barrett plans to bomb another Shinra reactor, but learn that Shinra themselves intend to drop the reactor’s plate on the city below with Avalanche taking the heat. While traversing the reactor they encounter Reno & Rude the former of the two Cloud had previously fought while protecting Aerith from their pursuit. The duo are there to ensure that the plate falls as planned, while Tifa, Barrett, and Cloud are distracted from the fight Rude sets off the self destruct of the plat succeeding and escaping with Reno. As Sector 7’s slums deal with the destruction caused by Shinra, Cloud & co. return to do what they can to help the citizens. In the midst of the chaos Aerith is taken hostage while protecting Barrett’s daughter Marlene. Upon rescuing Aerith she reveals she’s a member of a now near-extinct ancient race known as Cetra whom are connected to the “Promised Neverland” that Shinra has been using to absorb Mako. Sephiroth attacks Shinra HQ to acquire Jenova; an alien being responsible for the extinction of the Cetra people, killing the Shinra President in the process. Rufus, the President’s son assumes control of the company in wake of his father’s death. After being defeated by Cloud and his group they escape and face off against Sephiroth & the Whisperers. After separating Cloud from the others he attempts to convert him to his side, but fails & defeats Cloud in battle. Deciding to not kill Cloud he instead leaves him as Cloud and the remaining forces of Avalanche leave Midgar to stop Sephiroth. An alive Zack Fair seemingly from another dimension suddenly appears defeating Shinra soldiers and carrying an unconscious alternate dimension Cloud with him.

Final Fantasy VII trades its former strategic based combat system for a much more grounded action based combat system.

Final Fantasy VII changing from a strategic JRPG to more of an action-RPG for its combat formula feels a bit odd at firs, especially if you’ve never played any of the handful of modern mainline Final Fantasies. The slowed combat feels a bit casual at times and sort of simplifies things to a soft of embarrassing level. While it’s not quite hand holding level, it does get to a point where there’s not much heart-racing challenge until the middle bit of the game when enemies actually do require an adamant amount of time to figure out the best path to victory. Contrastingly, if you had come off of a playthrough of say Final Fantasy XV then you’ll feel right at home wit the not-so-new combat of Final Fantasy VII Remake. It’s been theorized that Square changed the Final Fantasy combat to appeal to Western audiences due to the prominent rise in action games. Given Square Enix’s own rise in the West he past decade and a half or so it makes sense for their 3D titles Kingdom Hearts become as popular as it is didn’t help the classic formula either. The story is full of emotionally driven characters with their own personal goals & determinations. Standouts for me personally were Cloud, Barrett, Aerith, Reno, Rude, and Jessie, especially in regards to voice acting. For this game to have a first-ever voice over experience (and by this game I obviously mean FFVII & not the series as a whole), the voice cast provided a wonderful performance throughout the run. The story itself has a great message about us needing to be a bit more mindful of our natural resources with pollution and what not which is a bit unique for a 90s game. It doesn’t go off the deep of being too preachy and is sensible with it’s arguments.

Sephiroth returns to break Cloud and his friends.

THE BAD: It should be noted that despite being advertised as a “remake” Final Fantasy VII…let’s say “2020” is more of a reboot of sorts for that universe of characters and potentially the entirety of the Final Fantasy franchise as a whole. While it’s naturally expected for seasoned veterans to be upset by this most of the first main chapter of the game is intact with some sure to be nit-picky parts here and there such as the introduction of the Whispers; time traveling spirits that see to destiny remaining as such and going unchanged. This understandably feels like a cop out, but if Square honestly has plans to use Cloud & friends long term post this new “remake” universe then that’s also understandable. After all they’re almost certainly the most recognizable characters in the Final Fantasy franchise currently and maybe the Final Fantasy XV universe following close behind considering how huge that game got. The new combat mechanic while welcoming to newcomers does aide in a lack of challenge in the first half of the game. Almost to being frustratingly easy, thankfully enemy difficulty rectifies this as the game goes on. Side Quests also have a bad habit of feeling like uninspired busy work. You’d think that with the evolution of side stories in these types of games Square would do a bit more to make them worth while, but if this was for the sake of authenticity & faithfulness to the original game then that’s fair.

Square Enix brings about the dawn of a new era for Final Fantasy VII.

OVERALL THOUGHTS: Final Fantasy VII will have a love/hate relationship for old and new fans of the original and the series in its entirety, but for what it accomplishes as a remake I think it helps expand the Final Fantasy series keeping it’s longevity ensured. In addition to spinning off the Final Fantasy VII story into it’s own universe something Square Enix has previously attempted before with tie-in media and such. I think Square has what it takes to satisfy both sides of the Final Fantasy fandom with old and new fans, and so far this is a pretty excellent start.

0 notes

Text

How American Colonialism Paved the Way for Immigration

The continent of America has been a source of hope and a font of ambition for explorers since its first discovery by vikings in the Middle Ages. The original voyages here were undertaken by exiles living in Iceland and Greenland and adventurers seeking profit. When Columbus first sailed west, he was not looking for the Americas but rather overseas routes to India for access to the goods of the silk road which the fall of Constantinople made inaccessible for Europeans. The pilgrims on the Mayflower came seeking a safe haven to practice their faith when they had none in their own homeland. For many island and peninsular’d peoples, overseas expansion was their only means of acquiring new wealth and prosperity. The English, certainly, fit this bill. The failure of the Hundred Years’ war showed that there was no expansion to be had on Continental Europe for the British. They had two options: wage more futile wars of expansion, or seek virgin lands and new sources of power abroad. That they and many others found in the New World.

Though Colonialism has many negative connotations to the modern world - particularly leftists - it shouldn’t be eschewed entirely. It has important ramifications for how our ancestors who eventually declared independence from their overlords viewed themselves and foreigners - even natives upon who’s land they found a new home. Though conflict existed, it’s important to note that many years before the humanity of their future adversaries was declared by their colonizers. The Spanish recognized those living in the New World as human in many legal documents and granted them the same rights afforded to continental subjects, and this was a view generally held even by the English. Most assuredly their civilization was primitive by the standards of Europeans, but it was a civilization nonetheless. It is not racist or demeaning to acknowledge the obvious fact that a tribal society that barely mastered fire is inferior technologically to one that erects permanent structures of stone and has mastery over gunpowder. More important to my essay here though is that most colonizers didn’t view others coming to their homelands as outright enemies. They were not so clannish as many on the Right would have us believe. Some of Connecticut’s first legal documents, for example, spelled out that aliens living the colony had the same rights of citizens. Even women had rights comparable to what we have today in Connecticut.

To be sure since the beginning of our nation fear over influxes of foreigners have existed and many attacks on our nation’s homeland proved a threat existed. But that did not stop many once troublesome minorities - Spanish, Germans, Italians, Irish - from assimilating to our nation. They came for new opportunities and because of what we stood for as a nation, and so they wished fervently to be a part of our nation and to be held apart from those who caused trouble. When given freedom and equal opportunity and having rendered the Republic service, they found what they desired in spades.

What’s extremely curious is the attitude many new inhabitants of Columbia took towards new arrivals, and their own hopes - particularly during the Civil War. The Union employed many regiments that were notorious for their foreign composition. Garibaldians and Irish Brigades are perhaps the most well-known, and in song, word, and deed they expressed pride in fighting for the Republican Union and with hope we would send them soon to liberate their own homelands so oppressed. Michael Corcoran of the Irish American Legion most famously said he fought with hope that the Union would be a home for all the foreign and oppressed as it was to his own people.

But where does this mindset come from? What is it’s origin? In the colonial ambitions of our forerunners, and of course in those hopeful immigrants who stood in reverence as they passed the Statue of Liberty as they entered Hudson Bay. When our ancestors came here, they wanted a new home where they could breathe free. Is it a strange thing that others may have the same hope, seeing our forefathers succeeding as such? Our ancestors’ chief goal was not a pure ethnostate. If that was the case, they might have stayed at home. At most one might say some of our ancestors sought religious purity, but even Christianity mandates friendship to the foreigner and does not mandate hostility to those of differing creed.

So in closing, after examination of our heritage one can conclude that it’s not hard at all to see how the construction of our nation was built upon principles and not blood-and-soil. One cannot find in our founding documents any evidence it was so, and early documents prove our forefathers in the least accounted for those who would follow in their footsteps. However, they would never have intended to surrender our ideals and our nation haphazardly to the world. They must be defended, lest they be lost; kept safe from the Know-Nothing and the Foreign Terrorist as well. But, also, from ourselves.

It is a commonly held principle in the West that magnanimity is a privilege of the strong. One cannot be charitable if one does not have the means or security to do so; to do otherwise is folly. We must have some assurance that our good deeds are not taken advantage of. If we cannot safely take in migrants, we do not do ourselves nor the tired and poor any justice. For when chaos and strife reign, prosperity and justice cannot. It is our duty not just to ourselves but to those who would seek refuge in our fatherland that we keep it a land of prosperity and security. For it is not the desire of immigrants to join our nation that should concern us most, but the fact that one day they might not and worse yet our own people will seek a new home. Our nation must be strong so it can be sovereign, or the Empire of Liberty is forfeit and the dreams of the Revolutionary Generation will have been for not along with their sacrifices. If the Republic falls, not only we but the world shall suffer. If we shrink from the destiny Fortuna has allotted us than in the future we shall rue the day our cowardice consumed us and a far crueler master is the fulcrum upon which the world turns. Therefore, if it becomes unsafe to take immigrants we should most surely stop. We must use our judgment and be guided by prudence. Our immigration system is one of the most successful in the world, with a record stretching back almost 200 years. As Theodore Roosevelt succinctly pointed out, if we become a dis-unified patchwork of bickering ethnicities this country will no longer be safe for anyone!

As I have pointed out, the colonialism of our own ancestors paved the way for and inspired the immigrants who have joined our nation and will come to our country. One tempted to criticize colonialism must be at some point forced to admit that without it, the “liberal” order he values and enjoys would never have been built. Indeed, it might not be far fetched to say that our own Founding Fathers being so abused by the British realized the potential harm colonialism could bring not just upon foreigners and their homelands but the colonizers themselves! But at the same time it was this free spirit of exploration and this ambition to build an empire from sea to shining sea upon which the sun could not set that built this nation and become an inspiration to all the world, and drew many from their own lands to join us in the New Order of the Ages. Along the same line, one who praises colonialism and how it built our nation must admit the example they gave to others and that it is only natural that a nation built upon the great premise of Liberty and Justice For All would indeed bring the tired, poor, unwashed masses in awe to our great empire. Anyone who would shun the foreigner without just and reasonable cause must admit that in doing so he would dishonor his ancestors and is only by the mercy of Providence not placed into such a circumstance where he himself would be left adrift. Let us, therefore, in the spirit of our Founders, share our bounty with the world and keep it safe for posterity. For if this Light goes out, we may never see its like again to the misery of all the world. Let all four corners of the world come together and join us so we might shock them as we did at Lexington & Concord when we fired the Shot Heard ‘Round the World. Patriae Aeterna!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sensor Sweep: 9/30/2019

Weapons (Ammoland): On the Internet, and in print, many people claim that pistols lack efficacy in defending against bear attacks. Here is an example that occurred on freerepublic.com: “Actually, there are legions of people who have been badly mauled after using a handgun on a bear. Even some of the vaunted magnums.” OK, give us a few examples. As you claim “legions”, it should not be too hard. I never received a response.

Fiction (Walker’s Retreat): As the book just went live in paperback, product linking will take a few days, but both versions are meant to be linked. I’ve set it such that any paperback purchase gets you the ebook for free. The same applies to other features such as Look Inside.

BACKERS! I’ve ordered your copies. They’re due to arrive at my house between the 8th and the 16th. I will begin turning around and sending them to you as soon as they arrive.

RPG (RPG Pundit): Lion & Dragon contains a bestiary chapter, which has 40 different entries for creatures (not counting 13 animals and a bunch of entries for human NPCs; and also not counting Demons which have their own section in the “Summoning” rules of the magic chapter, alongside the homunculus and the golem). Many of these monsters have names that you would see in any number of OSR/D&D monster manuals, but their version in L&D is very different, being based on medieval lore and styling.

Fiction (Cirsova): The idea is that wars on Earth created a race of albino Khan Noonien Singh-esque Mutant supermen whose intellect and self-determination put them at odds with a socialist global superstate, so said superstate booted them and other non-Mutant freethinkers off to the moons of Jupiter. The societies and states on the moons of Jupiter have a nominal perpetual peace, except they’re actually in a state of perpetual strife and intrigue acted out via agents.

Comic Books (Paint Monk): It’s the same group who thought Avengers: No Road Home and Savage Avengers were good ideas. Editorial is a milkmaid and Conan is the cow.

I feel like I’m beating the same old drum. Conan the Barbarian is a terrible comic. Jason Aaron’s prose is just abysmal. Mahmud Asrar’s art is merely serviceable in that for every brilliant panel there are two or three he must have drawn while sleepwalking.

Ian Fleming (M Porcius): One of the issues one might raise about some of the first four 007 novels is that Fleming didn’t do much to flesh out the lead villains. For example, we spend very little time with the Spangs, the twin brothers who head an American crime family in Diamonds Are Forever before Bond sends them to hell with his .25 caliber Beretta or a handy 40mm anti-aircraft gun.

RPG (RPG Confessions): These vocabulary words are useful in that they summarize complicated concepts, and that leads to greater communication. But we live in a time where everyone skims, and no one is very good at reading for context anymore, and subtlety is gone and nuance is out the window, and…I guess what I’m saying is, “Sandbox” and “Railroad” are positioned in our current lexicon of geek patois as Yin and Yang, a positive and a negative, one to emulate and the other to assiduously avoid at all cost.

History (Swords Sorcery): During the French and Indian War (1754-63), the French capture of Fort Oswego on the shore of Lake Ontario opened the rich farmland of the valley and the homes of the British-allied Mohawk nation to military threat. The valley survived the war mostly intact. It was a very different story twelve years later in the American Revolution.

Book Review (Everyday Should be Tuesday): If it wasn’t entirely clear after Cold Iron that Cameron is writing an Epic Fantasy with a capital-E and capital-F, it certainly isn’t now. This is also definitely Flintlock Fantasy—early modern guns play a much more significant role in Dark Forge than they did in Cold Iron.

Cinema (Postmodern Pulps): Last Blood, on the other hand, appears to have been conceived for the sole purpose of getting to the last 20 minutes of the film, and no one gave any real thought or care as to how the film got there. In order to talk about this, I’m going to have to deal with some extensive plot spoilers, so now is your chance to bail now if you don’t want this.

Fiction (Hi Lo Brow): Sixty-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Fifties (1954–1963) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

D&D (Skulls in the Stars): WG5: Mordenkainen’s Fantastic Adventure (1984), by Robert J. Kuntz and Gary Gygax. This adventure is reeeeeally old school, even though it was published in 1984! The name sounds a bit silly, but don’t let it fool you: this adventure was first written in 1972/1973 by Robert Kuntz in order to challenge the skills of none other than Gary Gygax, who used his wizard Mordenkainen! It is a quite punishing dungeon.

Fiction (Superversive): The Goddess Gambit is the series’ first novel, telling the tale of a post apocalyptic Earth, ravaged by a mysterious event called “The Storm.” Humanity is now primarily concentrated around an immense fortress called the “Zigg,” with the fortunate pure ones living inside in relative luxury, the unfortunate– mutants, aliens, and general undesirables– living in slums clustered around it. (If you’re thinking Final Fantasy VII‘s Midgar, you’re on the right track.)

Storytelling (Wasteland and Sky): What I dislike the most is anything that makes the universe smaller. Any story device that clips the wings of potential from the outset is one I cannot get behind. And, unfortunately, this has happened more and more over the last decade. There are two examples that are functionally the same thing, but both are very good at making me lose interest in your story.

Gaming (Bell of Lost Souls): Come take a look at some of new rules and changes to existing ones that turn up the newest Warhammer Underworlds season’s competitive heat! Source: https://www.belloflostsouls.net/2019/09/warhammer-underworlds-beastgraves-seasonal-delights.html

Westerns (Paul Bishop): If I could only choose one Western novel to recommend, it would be The Cowboy and the Cossack. The traditional cattle drive formula is given a refreshing twist when fifteen Montana cowboys sail into Vladivostok, Russia, with a herd of five hundred longhorns. The experienced wranglers are fired up to drive their herd across a thousand miles of Siberian wilderness, but are startled to find a band of Cossacks—Russia’s elite horsemen and warriors—waiting to act as an unwanted escort.

Horror (Too Much Horror Fiction): So within a couple months I’d tracked down Lansdale’s 1987 novel The Nightrunners (Dark Harvest hardcover 1987, paperback by Tor, March 1989). I recall coming home one afternoon from the bookstore I worked at with my brand-new copy, going into my room, locking the door and then reading it in one white-hot unputdownable session. That had never happened to me before; I usually savored my horror fiction over several late nights.

Edgar Rice Burroughs (DMR Books): February 1912 saw the ground-breaking publication of Under the Moons of Mars—later rechristened A Princess of Mars—in All-Story Magazine. Readers clamored for more adventures on Barsoom and Edgar Rice Burroughs gladly obliged. The first installment of The Gods of Mars was published in January of 1913. ERB, no fool, ended TGoM on a cliffhanger. John Carter fans demanded the conclusion to the saga and Burroughs delivered the goods. The Warlord of Mars saw its first publication in All-Story beginning with the December, 1913 issue.

Comic Books (Brian Niemeier): Everybody has a theory of how the American comic book industry died. “It was the early 90s investor boom,” some say. “The glut of variant covers and similar sales gimmicks created a bubble, and when it burst it took out the direct market.” Others lay the blame on publishers driving out seasoned writers and letting rock star artists run the show.

Detective (Moonlight Detective): An anonymous comment was left on my review of The Fort Terror Murders explaining Van Wych Mason’s long-running Captain Hugh North series has two main periods. The first period covers the fourteen novels published between 1930 and 1940, which have the word “murder” or “murders” in their title and “tend to have elements of the Golden Age detective story,” but the second period moved away from detection towards more spy-oriented intrigue novels – starting with The Rio Casino Intrigue (1941) and ending with The Deadly Orbit Mission (1968).

Dashiell Hammett (Black Gate): Sam Spade, the quintessential tough guy shamus, appeared in a five-part serial of The Maltese Falcon in Black Mask in 1929. Hammett carefully reworked the pieces into novel form for publication by Alfred E. Knopf in 1930 and detective fiction would have a benchmark that has yet to be surpassed. Hammett, who wrote over two dozen stories featuring a detective known as The Continental Op (well worth reading), never intended to write more about Samuel Spade, saying he was “done with him” after completing the book-length tale.

Sensor Sweep: 9/30/2019 published first on https://sixchexus.weebly.com/

0 notes