#shows that irrevocably changed the way I consume every other piece of media

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

aragorn trying to return the evenstar to arwen and her saying “it was a gift. keep it”

cas trying to return the zeppelin mixtape to dean and him saying “it’s a gift. you keep those”

#spn#destiel#I’m lotrnatural posting#shows that irrevocably changed the way I consume every other piece of media

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do you feel about derivative art? I'm guessing you approve since you're big into fanfics. Is art that's derivative as good as original art? Could a well made video critique of a film be better then the film? Or a fanmade rewrite be better then the original book? And yes I know nothing "original" exist, but that's not the same thing as art that is obviously derivative. And the big question. Should artist be allowed to make money off derivative art?

For me it’s an all around “Yes.” I’ve read fics leagues better than published novels. I’ve seen fanvids far better than films. Granted, when you get into the subject of visual media you run into things like finances and access to technology. Anyone can craft a story with words, but only a few have the budget and tools required to re-create the sort of Blockbuster films we’ve grown used to. But why in the world would that very specific style be the only “good” art out there? Obviously it’s not. If anything, we value limitations in our art. Six second vines shot on cell phones are adored and can lead to lucrative careers. Films like the Blair Witch Project want to mimic an armature cinematography, like these people really were just shooting what they could while running for their lives. Amateur does not in any way equal lesser. To say nothing of the fact that fans have shown time and time again that a passion for the material and a huge amount of work ethic is more than enough. As the recent Loki logo abomination attests, all the money and resources in the world doesn’t guarantee taste---or success. Outsiders to fandom love to criticize the “horrible” fics they found when they dove into AO3 for all of ten minutes, but fail to acknowledge that you’re just as likely to find a terrible book when you pull one randomly off of B&N’s shelves. If derivative art is somehow lesser than we need to re-evaluate the comics industry. And every formulaic western, rom-com, police procedural. And every great author (there are a LOT) who wrote “classics” based off of other’s characters and worlds. Art is art. Mainstream art is in no way superior to fan art, no matter how much people still want to convince us of that.

The money question is, admittedly, waaaaaay more complicated. For me though it’s still a “Yes” simply because of how fandom functions. That is, we need the canon. Even if it becomes outdated, or is considered offensive, or is absolutely terrible compared to what the fandom has now produced, people will STILL consume that material (and more importantly buy it) in order to get access to all the good fan stuff. I’ve simply never bought into the argument that derivative works are a threat to the livelihood of the original piece because they depend on that piece. All my friends are in a fun discord for TV Show X. They’re producing all these fics I want to read. I’ve heard that Show X is actually pretty bad, but I’m going to watch it anyway because that provides me with the context that produced all this other stuff. It’s the foundation, the blueprints, the golden ticket to get inside the fandom. Will every fan do this? No, some do bypass the canon and just dive right in, but the majority of them will. Meaning that rather than posing a threat to the original author’s livelihood as most people assume, fanworks help keep mainstream content alive. Adding a price to that doesn’t change anything. If someone offers me a fic for free I’m gonna tackle the canon book first. If someone offers me a fic for $10... I’m still gonna tackle the canon book first. Either way the author gets paid and are likely to get more if fans use their work as an entry point into the fandom. “I wouldn’t have read/watched your stuff at all, if it weren’t for the fact that I want to read the stories my friend is now producing.” Giving that friend some rent money is the least we can do.

(There are obviously other arguments against making money off of derivative works, two of which boil down to “It’s against the law”---which funnily enough we create and control and can change if perspectives change---and “They’re my creations and I don’t want you messing with them, let alone making money off them.” I’ve got a lot of feelings regarding that one and in an effort to save a bit of space I’ll boil it down to a very unkind response: Too bad. Transformation is at the heart of human interaction with art. If you didn’t want that you shouldn’t have given it to the public in the first place. Authors don’t get to police how fans interact with their work: “I love it when you take the time to write me glowing reviews! .... oh, but not when you write another story. Please continue making awesome fan posters that promote my work! ... but not one with those two characters kissing ew.” Authors don’t get to dictate how fans interact with the art they’ve put out there; how much of it is active and in what ways.)

We also have to consider that we’re already in a world where those lines are irrevocably blurred. Why does E.L. James or Anna Todd get to make a fortune off of their barely changed fics? Why do artists get to sell their fanart but fic writers are still largely terrified of lawsuits? Fans are already making money off their work---always have, really---and I doubt that’s something we can reverse. Whether or not it continues to grow is the real question.

Personally, I wouldn’t want to see derivative works commercialized, not because fans don’t deserve to earn money for their labor (we do), but just because that would irrevocably change fandom dynamics. We’re a gift economy and we’re built on that. Fandom has always been about progressive acts: be it writing about queer identities, providing accessibility accommodations decades before mainstream art did, or (and this is the kicker) helping to level out class differences. Meaning, mainstream art is often for the rich and the elite. Broadway shows are insanely expensive and impossible for most to get to. Movies prices have skyrocketed. Every company is creating their own streaming service, requiring that you pay three or four $20+ monthly subscriptions instead of just the one. It’s all about money and fandom is one of the few places where we still exchange art for praise and more art, rather than a paycheck. Fic is free. Fanvids are free. You guys want a cute drawing of this couple? All you have to do is send in a prompt ask and I’ll draw it! Sure, I’d also love it if you paid for a commission, but I’m going to keep creating free drawings on the side. When was the last time we saw a mainstream author go, “Please continue to buy my last story, but in the meantime here’s a free novel I’m putting up on my website. Hope you enjoy!” I mean yes, we do get things for free (especially when it comes to many games, apps, and some short stories), but not like in fandom. There’s a culture of giving that I never want to lose. Are we already doing commissions and con sales? Yes. Do we often ask for donations and payment? Yes. Should we be able to continue doing so without fear of legal action? I think so. But I don’t want a general sense of “I should be allowed to earn money off of this” get turned into “Well if I can earn money off of this why wouldn’t I?” I never want our work to exist fully behind a wall where the key in is your credit card number. Fandom is unique in its, “I made this thing because I wanted to and I shared it with you because I wanted to do that too, no strings attached” and that, I think, is worth protecting.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Going, going, (not quite but almost) gone: the sad state of local newspapers

True story: As a young, would-be journalist, I applied at the behest of my high school journalism teacher to the Hugh N. Boyd Minorities in Journalism Workshop. The program was a two-week intensive workshop open to high school students across New Jersey with an interest in journalism. It promised to provide the 15 or so selected participants with real-world experience in the field absolutely free of charge, as local newspapers across the state sponsored the event, covering all expenses for selected students. Having always been rather introverted and somewhat shy, I didn’t think my writing was good enough to make the cut. But to my surprise, I ended up being selected and was sponsored by my hometown newspaper, The Record of Bergen County, aka The Record (or, so it was called at the time). The experience was transformative for me, and gave me my first insight into life as a journalist. I’d go on to study journalism as an undergraduate student at the University of Florida, starting off in print but switching to broadcast, and working professionally in the field for more than a decade for CNN, NBC, ABC, Univision, and more. And for a time, I briefly took a job as the lead social media editor for none other than the local newspaper that helped give me my start in the business: The Record of Bergen County.

(fun fact: The Record broke the 2013 George Washington Bridge lane closure scandal which made national and global headlines) This week, I chose to take a closer look at local newspapers, and in doing so, briefly examine why they’ve struggled to remain relevant in a changing industry (I’ll only scratch the surface, because I could probably write an entire dissertation on this topic). It’s actually quite sad, as I firmly believe that local newspapers and beat reporters are critical to freedom of the press and unbiased, balanced, and fair reporting. Sadly, the digital age has done irrevocable damage to this industry. And I hate to say it, but digital and social media are almost solely responsible for the demise of newspapers, and sadly, I’m a part of that problem too. As a tail-end millennial who came of age with the internet, if the news isn’t on my smartphone or easily accessible via an app or a free website, I quickly lose interest and seek my information elsewhere. I can’t remember the last time I had a newspaper subscription, or even purchased a newspaper. I recognize how important they are, I just have so many other options for news consumption now that I just don’t turn to newspapers anymore. Freedom of the press

Local newspapers have been part of the fabric of this country since as early as the 1600’s. Every journalism student remembers studying the great circulation wars of the 1800’s between Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. If not, everybody remembers how fun it was when instead of class, our teachers took a day off from teaching and instead showed “Newsies” on VHS in history class. It never gets old.

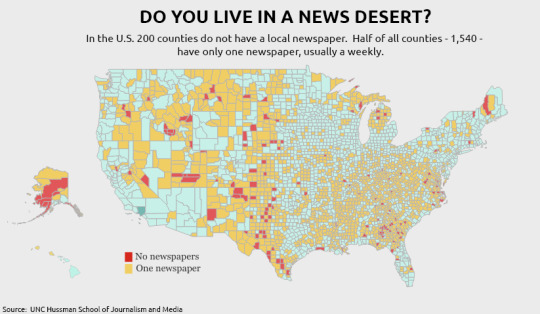

(truer words have never been said, Jack Kelly) But the rise of television news, and eventually digital and social media, pushed local newspapers aside, as audiences had a quicker, easier way to access news on-demand instead of waiting for the morning paper. According to a recent report by researchers at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 300 more newspapers failed since the fall of 2018 bringing the death toll to 2,100. That’s 25 percent of the 9,000 newspapers that were being published just 15 years ago. It also noted that there are about 200 “news deserts,” or communities without any local newspapers. Most of those news deserts are in economically challenged rural areas, but more and more, even the economically advantaged suburbs are feeling the pinch too.

(via UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media) The danger here? Local papers highlight and elevate local stories we might not otherwise know about, but we absolutely need to care about. What’s going on in our schools, with our local elected officials, within our communities, local zoning and budget decisions that impact our daily lives. They provide a micro-level guide to the things that impact us every single day. So if nearly all of your news is coming from social and digital media and their sometimes questionable algorithms, or television news that’s almost undoubtedly biased (at least in the U.S.), you really have to question whether you’re receiving fair, unbiased coverage. Dying, but not (quite) dead It was encouraging to see that while the industry is undoubtedly suffering, there are still some people who often consume their news via local newspapers. According to the Pew Research Center, people aged 65 and older account for most of the existing newspaper audience, roughly four in 10 of whom say they still often get their information from newspapers. This is about what I would expect from the older generation, but this sadly doesn’t say much for younger generations and their newspaper consumption. Only 18 percent of people age 50-64, 8 percent of people age 30 to 49, and a mere 2 percent of people age 18-29 say that they often get their news from newspapers.

And even among those 65 and older, newspapers are a pretty distant second in terms of the source they visit most often for news, as 81 percent of people in this age group cite television as the source they often use for news.

If you can’t beat them, join them In my brief time as social media editor for The Record, it was obvious to me that the paper was trying hard to adapt to a changing world, opening themselves up to methods they’d never had to use before. The same was true of most newspapers, even national newspapers like the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times. It has been interesting to see the ways in which these newspapers have branched out into new forms of media to adapt to the way people consume news today. I highlighted this in a previous post, but I’ve been impressed by the NYT’s foray into LinkedIn Live, creating immersive, engaging conversations on key stories, and giving the audience the chance to actively participate with the media. At its core, I’ve always said that the best thing about social/digital media was that it took what were always one-way conversations, and made them into two-way experiences for the audience and the content creator. And speaking of the Times, their efforts on Instagram are among my favorite. Beautiful portraits that would once only live on paper are now shared in a beautifully curated feed that is always so pleasing to the eye. Often, these are stories that wouldn’t typically make the front page of the paper, but the visuals are so stunning that they tell a story in and of themselves.

(via the New York Times on Instagram) Using local newspapers as a communications professional

Part of my renewed interest in newspapers came about when I was a communications manager for a small nonprofit organization. Our primary goal was to engage in state level advocacy on behalf of the state’s charter schools. Effectively that means, catch the eyes and ears of lawmakers and state your case so that when budget time comes around, they’ll make sure to enact a budget that ensures the survival of these schools. I learned that these lawmakers and influencers pay close attention to newspapers, perhaps even more than other forms of media, and so getting our agenda into the local newspaper was a large part of the work that I did. I would write (well, ghostwrite) opinion pieces for senior leadership, students and parents, and pitch them for placements in the local papers in the districts of the lawmakers we needed to reach, I would develop relationships with local education reporters, invite them to press events, give them quotes for their stories, organize editorial board meetings and more. Newspapers became a critical part of the work that I did, as were the relationships I built with members of the newspaper industry, and I’d imagine the same is true for other communications professionals. Much to my (pleasant) surprise, there are still some brands doing important work with traditional print newspapers. According to FORBES, “MasterCard placed a two-page spread in The New York Times, almost unheard of these days, to articulate its support for the LGBTQIA+ community and MasterCard’s support for GLAAD’s NEON Legacy Series, a photo and video collection produced by Black LGBTQIA+ creators. The ad states MasterCard’s commitment to equal treatment, equal opportunity and equal rights. The ad features both the MasterCard logo and the GLAAD logo.” I can’t find a photo of the ad anywhere, but I’m sure it was great! Of course, this is very different from the way the general public engages with newspapers, as they’re looking for unbiased updates on what’s going on in their communities. But it’s still nice to know there are still some communicators out here tapping into the power of local newspapers to promote their brands, and I was one of them.

(sigh. a beautiful sight)

A sad future for local newspapers Sadly, none of the statistics point to a revival of newspapers anytime soon, although I’m holding out hope. With fewer local papers, and increased reliance on (often biased) television and (often wrong) social media for news, I worry that this is just one of the unfortunate ills of the digital age we’re living in. Sadly, many local papers are unable to stay afloat despite employing every possible adaptation in the book, often succumbing to major buyouts by huge conglomerates, resulting in newspapers that are controlled by corporate interests and offer no true local, unbiased reporting.

And as for The Record? It suffered a similar fate in 2016 after it was ultimately bought out by Gannett, the nation’s largest newspaper chain. For folks like me from northern New Jersey, it was the end of an era. I still remember being saddened when I learned the news, even feeling a tad guilty that I didn’t stick around long enough to perhaps contribute to a more favorable outcome. While my time there was brief, I worked alongside some of the smartest, most passionate and hard-working people I’d ever met. They lived and breathed northern New Jersey, and they put their heart and soul into every letter of every story that went to print. But what happened with The Record has sadly happened to so many local newspapers with no signs of slowing down. As communications and marketing professionals, we certainly can play a role in trying to help revive the industry, but my fear is that any efforts we make would be too little too late.

0 notes

Text

3

TOWARDS AN ECOLOGY OF LOVE

(June-July, 2020)

“Let’s face it. We’re undone by each other. And if we’re not, we’re missing something.” -Judith Butler

Fire and Mourning I’m shaking. The sun is heavy on my neck and the crowd seems to shiver in flexed anticipation. The anger running through the protestors is hot like a spider bite. The chants have all the usual words but today they sound like a new language, pulsating with a rhythm as unmistakable as it is unknown. Tears and sweat and names. My mask is damp and stale, dank breath and odor-eliminating chemicals wash back down my throat with every syllable. Then, the sun goes white and the police, without warning, jump us. Screaming. Protestors and cops collapse into blue knots, plastics are tangled up. Fists, legs, batons. Water bottles fly. I find my partner and pull her away from the cowering cop at her feet. A horrified girl in a faded tye dye top pushes her way forward, shrieking pleas for de-escalation. But we have slipped into a dark beyond, out of reach of such luxuries as deliberation, planning, and respectability...

The scuffle ends with several on our side arrested and many more beaten bloody. Whoever has the megaphone manages to march us across the city for several hours, but the veil of control has been torn. Paint goes up on every wall in the city to elated hollers. Squad cars are destroyed, at least one burns. The police are now eerily absent. We march back towards the towering art deco skyscrapers at the city’s center, monuments to abundance we’ve never known. There, a wall of riot cops awaits us. Gold light catches the edges of a gilded cupola and stains the cream colored marble like marmalade. The city would be so beautiful, if it were ours. Cracks, screams, gas. The next few hours are a blur. Running, terror, bravery, fire, hope, inspiration, ingenuity. The police deploy dispersal technology more than once but to no avail. The remaining mass of people have become something else. At times, to the police’s genuine horror and visible surprise, we push them back with a barrage of water bottles, debris, banana peels. When necessary, we melt back into the city only to reappear again moments later, one block over. At some point, word gets around that all but two of the bridges had been raised and we were trapped...

A firework rips through the police line to cheers. The cops swear and slip. Strontium carbonate burns bright red streaks across my eyes and whispers out. The police fracture into a million tiny pieces. An ATV donuts wildly and peels off straight at the jagged, trembling row of officers. Dumpsters are moved to prevent ambush, coordination flows like a river, without words. Motorcycles go up on one wheel. Eventually, we realize a curfew has been set, effective in twenty or so minutes. Someone has mounted a horse. There’s nowhere to go and it begins to feel as though the police are trapped down here with us, as opposed to us with them. Windows are smashed as darkness falls. The man on horseback charges forward, into the black and orange of the night...

The police would go on to make over 400 arrests by the end of the night, with over 80 officers reporting injuries in what turned out to be one of many, simultaneous riots taking place across the country. What I saw that night had previously been unthinkable to me. The city had flexed its anarchic muscle after decades of slumber and found it was still strong, and the police, shockingly weak. I remain struck, too, by the frantic way the police attacked. No one could be surprised at the lack of provocation nor the lack of shame, but what I did not foresee was the palpable panic emanating from behind their shields. And I am beginning to understand why we scared them so–we had come to mourn. Not to “resist” or to march or to curse DJT, but to mourn. We were there to grieve the ungrievable, to say the unsayable: that we will no longer accept no-life, we will no longer accept bare-life, that we are indeed connected, that we are hurt by this loss and every other, that we will give them a fight, that we will defend ourselves and each other, that this order is no order, and, that we deserve so much better. Our mourning was a radical negation of a system that tries to maintain an unnatural space between us, that seeks to limit experience to individual (or consumer) experience, that attempts to constrain feelings to personal feelings. Our mourning was dangerous. The cops were right. And their panic was not just at our finding strength in each other, but that they found themselves with none...

Judith Butler describes mourning as a process of transformation as well as one of revelation, in which we are exposed as being bound up in each other, our “selves” products of our relationships to each other, socially constructed, interdependent. When we lose, we change, because what we were was dependent on what we lost. This state or process of mourning makes possible the apprehension of our interlocked-ness, our interwoven-ness, in which “something about who we are is revealed, something that delineates the ties we have to others, that shows us that these ties constitute what we are, ties or bonds that compose us… perhaps what I have lost ‘in’ you, that for which I have no ready vocabulary, is a relationality that is composed neither exclusively of myself nor you, but is to be conceived as the tie by which those terms are differentiated and related.” There is no you and there is no me, rather there is a you-me and there is a me-you.

Can mourning be the only site of such apprehension? Mourning is an extreme condition, contingent on loss and suffering, a painful process, where these links that compose us are stretched and then snapped. This severance is gradually accommodated in a transformation. However, these links to one another just as much exist before this point of breakage, before the moment of loss, and there is then no reason they cannot be pulled at, plucked and strummed, like the strings of a guitar, until that which irrevocably binds us to each other achieves a resonance or vibration that no power can obscure. This resonance, this song, this elevation of our bonds to the level of naked visibility, could usher in a moment of universal recognition of our interdependence, our interconstitution, our intervitality, that, if properly politicized, could hold the key to our liberation from the prison of capitalist relations.

The stubborn fact remains that these links, these ties, are currently obscured, mystified, hidden, or outright suppressed and attacked. We cannot politicize our ties if we cannot see them and we cannot see these ties because we are told at the level of ideology that they are either not important or, more maddeningly, that they are not there. The integrity of these links is further corrupted and degraded by the rising power of debt. Perhaps most troublingly, we humans are being transformed by supposedly liberatory technology into unfeeling components of a networked machine, incapable of empathy or solidarity. It is this final development that, when complete, could represent a point of no return, a total obliteration of the ties that both constitute us as individuals and define our humanity. If this subsumption of the human by the technofinancial machine is allowed to continue, there will soon be nothing left to mourn.

Capitalist Realism and Neoliberal Ideology Ideology is the first obstacle we encounter when tracing the gap between us and a resurgent solidarity. Neoliberalism is the dominant ideology in our time because of the hegemonic power the neoliberal bloc has accrued over the last five decades, infiltrating every level of government, media, academia, and economics. Hegemony allows the ruling class’ ideas about society to appear as if they are bubbling up from within each of us, as opposed to being imposed on us from above. As Nancy Fraser succinctly puts it, summarizing Gramsci, “hegemony is [the] term for the process by which a ruling class makes its domination appear natural.” Today, neoliberal hegemony makes the dominant ideas of the ruling class inescapable and nearly ubiquitous and yet, uniquely difficult to distinguish. A pervasive atmosphere of social-darwinism, savage competition, short sightedness, and nihilistic indulgence has become our ambient common sense. Hopelessness becomes a sort of wisdom, trust in each other and in the future becomes naivety. As Mark Fisher states in his book, Capitalist Realism, “The prevailing ideology is that of cynicism.” Nothing is possible, and it’s foolish to believe otherwise. It could be said that the apprehension of our ties to one another is the apprehension of the political, but the political under neoliberalism has been effectively neutralized. Neoliberal ideology attempts to situate us in an eternally post-political moment. The future is no longer contested space, it was sold to the highest bidder long ago.

Reinforcing this ideology is a material precarity that has come to make up the texture of life for the service underclass of neoliberal society, as well as more broadly characterizing the spirit of work for all in the new economy. Solidarity gives way to brutal competition, coworkers become competitors, friends become networks. No one job is enough; we are constantly seeking the next opportunity for advancement, overlapping work schedules clash, disaster looms, familial relations fray, neural stimulation overloads and feeds back into wave after wave of crippling anxiety, at best. At worst, violence. This precarity and its accompanying anxiety, while horribly traumatizing to the overwhelming majority of people, has very advantageous qualities from the perspective of capital. In an interview with Jeremy Gilbert, Mark Fisher points out that, “anxiety is something that is in itself highly desirable from the perspective of the neoliberal project. The erosion of confidence, the sense of being alone, in competition with others: this weakens the worker’s resolve, undermines their capacity for solidarity, and forestalls militancy.” At multiple levels of our waking (and dreaming) lives, the idea that you are not only alone but in eternal competition with every other person is reinforced, and the effects of such a social arrangement can be seen in the rapidly spiking suicide tally, spectacular violence, pharmacological dependence and abuse, and the numbers of people reporting depression, burn out, and especially loneliness.

We see this “lone-wolf” mindset very clearly when we consider the popular cultural output of Western capitalist society. In the same interview, Fisher points to the rise of hyper-competitive game shows as a manifestation of the social darwinism at the center of neoliberal thought. These aptly named reality shows, like Apprentice and Big Brother, revolve around “individuals competing with one another, and an exploitation of the affective and supposedly ‘inner’ aspects of the participants’ lives.” He continues by pointing out the way in which reality television feeds back into and constructs the reality of its audience: “It’s no accident that ‘reality’ became the dominant mode of entertainment in the last decade or so. The ‘reality’ usually amounts to individuals struggling against one another, in conditions where competition is artificially imposed, and collaboration is actively repressed.” One could endlessly list the names of these types of programs that have proliferated in the last decade or two in America, many with great commercial success.

Another trend emerging in the superstructure, more or less concurrently, is a sort of melancholic self-awareness of the brutal and total competition our lives have been reduced to. We can most easily locate this trend in music. It can take the form of a depressive acceptance of the shallowness of our relationships or perhaps a declaration of exhaustion, a celebration of outright antisocial behavior, or submission and defeated withdrawal. Oftentimes, these songs make heavy reference to a handful of favored barbiturates, opiates, or dissociatives. We can most readily see this in the relatively recent rise in popularity of “xanax rap,” as well as in some drill and trap music (21 Savage or Chief Keef come to mind). On the other end of the musical spectrum, we could look to the resurgent popularity of emo music, especially the hyper-personal, heroin addled, lo-fi bedroom varietals (artists like Teen Suicide or Dandelion Hands have amassed millions of streams and a cult following without the backing of a major label).

But even the ostensible “winners of the game” are not insulated from the melancholic deterioration of the social fabric. One song in particular off of Kanye West’s manic 2016 album, The Life of Pablo, stands out for the stark clarity with which it addresses the crisis of relations brought on by the neoliberal economy. On “Real Friends,” West laments the way his friendships have been transformed. But one gets the sense upon listening that this isn’t just the story of a star narcissistically complaining about the way people from his past attempt to use his name or piggy back on his success; that’s simply the context. The song is, at its core, about how the insatiable hunger that neoliberalism forcibly inscribes in each of us, the end result of a decades long process of privatization of risk, erodes friendship, sabotages love, and destroys family. “Couldn't tell you much about the fam though/ I just showed up for the yams though/ Maybe 15 minutes, took some pictures with your sister/ Merry Christmas, then I'm finished, then it's back to business.” There’s no time for family gatherings. Time is money, there’s not enough of it and there never will be. Your friends are simply biding their time, lying in wait for a chance to use you for their own advancement. There’s a paranoia here, but as a fellow participant in the same savage game, you understand this paranoia to be justified. “Real Friends”, while rightly lauded for its “truth” and relatability, unfortunately functions as another whirring cog in the propaganda apparatus, normalizing the growing space between each of us and presenting cynical, opportunistic relations as “just a fact of life.” West seems to echo Fisher’s bleak assessment that “the values that family life depends upon – obligation, trustworthiness, commitment – are precisely those which are held to be obsolete in the new capitalism,” but without the critical edge. Our ties to one another, if they are acknowledged at all, are deemed simply useless and perhaps even a little bit risky, much like an appendix: an archaic, forgotten form that serves no useful purpose for today’s human, but can sometimes lead to infection. Bourgeois art, even art able to successfully express the darker qualities of the capitalist system, only reaffirms the status quo and further entrenches the ruling classes ideas about our relations to one another as the de facto common sense.

Debt and Bad Faith We next see these same social ties corrupted and corroded at the level of economics. The rise of credit, debt, and finance has transformed interpersonal relations under capitalism so as to be dominated by bad faith and suspicion. It’s quite common today for people to be heard bemoaning the transactional nature of relationships. But what exactly does this mean, and from where does our compulsion to calculate the incalculable emerge? Cartographer of the debt state, Marizzio Lazzarato, at first seems to echo some of Fisher’s observations in his 2012 book, The Making of The Indebted Man, pointing out that, “under conditions of ubiquitous distrust created by neoliberal policies, hypocrisy and cynicism now form the content of social relations.” Lazzarato describes many of the same symptoms of capitalist realism, but forgoes any discussion of ideology in favor of a somewhat more concrete causal chain: the creditor/debtor relationship.

In America today, debt is nearly ubiquitous and ownership has become an optical illusion, a disappearing act. Everything can be paid for later. Consequences can be deferred indefinitely with a solid line of credit. In this way, debt is sold to us as freedom, or perhaps more specifically, as opportunity. But of course, as is true of most things under neoliberalism, what is claimed and what actually is are two very different things. Lazzarato explains that debt can be understood as an obligation over time, both a promise and a memory. As a result of decades of neoliberal policies, personal debt has exploded in the United States and around the world. Personal debt acts as a form of social control, ensuring economic integration and encouraging one to prioritize “solvency.” This “solvency” usually manifests most visibly as an aversion to risk, a self-policed austerity, and general conformity so as to make good on one’s future obligations (to pay the debt).

The compulsion towards solvency appears in our personal lives in a wide variety of ways, unique to our station and interests. In some ways, even a grade schoolers fixation on popularity could be called a manifestation of debt society’s preoccupation with solvency. Obsession with outward appearances and “who is hanging out with who” is perhaps a primitive understanding of debt as a social relation. Even before taking on personal debt, children are shown that one must appear to be a person who will make good on their debts and thus be worthy of lending or more generalized opportunity. Parents often encourage their children’s involvement in a wide variety of extracurricular activities, not because their child is passionate, but largely for involvement’s sake. In debt society, being a well-rounded, “whole” person makes you deserving of investment. What was once your private activity or leisure time is now folded back into the economic as debt society implores you to constantly work on yourself and, with the development of social media, to publicly exhibit these favorable tendencies in yourself, proving over and over again that you are indeed viable, solvent, and a safe and potentially lucrative investment opportunity. In my own professional life as an artist, I am expected to broadcast or signal my practice’s (and thus my own) solvency at all times. Instagram has become artists’ preferred medium for the transmission of these displays and through “stories” and posts, we carefully curate an image of productivity, attendance, viability, and social integration and ascendence. We outwardly project the idea that we’re working hard in our studios, that we’re networking properly through studio visits and the obligatory cruising of exhibition circuits, that we’re reading the right books and thinking not just critically but, correctly, and that our work is already being collected and invested in, all in order to facilitate personal access to future opportunity.

In other spheres of life, this process plays out in much the same way, albeit with some largely aesthetic quirks or differences. For the cognitive worker, already a member of the upper-middle class, perhaps one shares their numerous camping excursions to impart a sense of their connection to the earth and adventurous spirit. For the service class, perhaps it appears as a public chronicling of their work ethic and commitment to upward advancement, even at the expense of pleasure or non-material enrichment. The public deferral of pleasure can be used as an expression of one’s solvency, especially and tragically among the lower classes of debt society. We begin to see here that these performances or projections may have a class character to their manifestations. For the lower classes, one is expected to showcase dedication to advancement by highlighting a self imposed austerity. For the higher classes, one is expected to prove they’re not only deserving of their opportunities but are using them properly, to further improve themselves and become a more complete person. All of this theater is directed at an audience of one: capital. Much of what constituted life has been degraded to the level of rote performance, of literal Virtue signaling. When our desire for autonomous self fulfillment and development returns back to us, now as a directive of capital and as a measure of solvency, this is alienation completed. This is the total commodification of the human and of social life.

Over time, solvency comes to stand in for morality, a good person becomes a person who will “make good” on their promise to pay. We grow suspicious, slow to trust, and it’s generally considered “smart” to remain somewhat distanced from your fellow worker, ready to cast them aside at a moments notice, either because a new, more lucrative opportunity for exploitable relations has arisen or there is a sense that somehow your current relationship could hinder or damage your accumulation of social capital or even your access to real capital in the future. People become containers of undifferentiated “risk.” While this reduction of friendship to an economic calculus is reinforced and normalized by ideology, it can be traced directly back to the rise of credit and finance. Lazzarato explains that,

“the trust that credit exploits has nothing to do with the belief in new possibilities in life and, thus, in some noble sentiment toward oneself, others, and the world. It is limited to a trust in solvency and makes solvency the content and measure of the ethical relationship. The “moral” concepts of good and bad, of trust and distrust, here translate into solvency and insolvency… In capitalism, then, solvency serves as the measure of the ‘morality” of man.”

This imposition of the debtor-creditor relationship and its associated thought processes onto our social relations has had a disastrous effect on our capacity for solidarity and friendship. This reduction of trust to an arithmetic evaluation of solvency amounts to an outright attack on our bonds, our interdependence, our intervitality, well beyond the aforementioned psychological denial and ideological mystification. Debt corrodes and transforms our bonds, attempting to rob them of their revolutionary potential and leverage them towards our own management or government; our ties morph from the seeds of our liberation to become a critical node of control. This reduction, the mathematization of social life, made possible and prefigured the transformations yet to occur at the hands of computer technology. This conversion of the unquantifiable into the numeric perhaps primed us for a world governed by ones and zeros, binary options and no choices; a world of mathematically infinite opportunity but evaporated possibility, a world engulfed by digital mirage, where government has been exported and grafted into the minds of the governed, implanted by credit and sutured by tech. Credit does not simply reduce friendship to a transaction, but (especially in an environment of technologically networked acceleration), facilitates the dissolving of trust, morality, and love into accounting, of real and perceived solvency, of calculation, and of preformatted corporate connectivity. Debt catalyses our transformation from living, affective, creative, unquantifiable singularities into cold, accountable, predictable, math. Interchangeable parts. Fiber optic cable, mildly inconvenienced by our flesh’s relative lack of conductivity. Its need to piss, shit, and fuck.

Finance, Transformation, Meaning It could be argued that a paradox emerges when this drive towards a total accounting arises at the same time as the fateful decision to free the United States dollar from the gold standard is made. At once, ideology and the rise of debt reduces relations to calculations, everyday life to math while the total detachment of the sign (money) from the referent (gold) unchained valorization from the real world, opening up fictitious space for fictitious valorization. The paradox lies in the fact that any truth once found in accounting was obliterated by Nixon’s decision while workers are now compelled by debt to recognize and submit to the quantifiable, the countable, as the only truth, the last truth. Where does this false truth get its power? What resolves this contradiction? Franco “Bifo” Berardi answers: “ Strength, force, violence.” Truth is an illusion and we are forced to adhere to finance’s directives not because there lies real meaning for us in the numbers or that we will one day crawl out from under our mountains of debt, but because we are coerced with violence: the violent expropriation of the means of our own reproduction, and the violence of everyday life, with its terrorist police and torturer bankers, predatory usurers and rapist landlords. With finance unleashed from the realm of the corporeal and the corporeal lashed firmly to the mast of the sinking ship of the mathematic (by debt), the real world becomes a prison without walls to the worker at the same time that the real world (and all of its inhabitants) becomes a trivial nuisance to capital. This sets the apocalypse in motion. As Berardi puts it in his 2011 book, The Uprising,

“When the referent is cancelled, when profit is made possible by the mere circulation of money, the production of cars, books, and bread becomes superfluous. The accumulation of abstract value is made possible through the subjection of human beings to debt, and through predation on existing resources. The destruction of the real world starts from this emancipation of valorization from the production of useful things, and from the self-replication of value in the financial field. The emancipation of value from the referent leads to the destruction of the existing world.”

As the world becomes simultaneously not enough (for capital) and too much (for the indebted people), the digital emerges, like a messiah, here to save humanity from reality and capital from its limitations. The digital promised humanity new horizons of democracy and liberty, and promised capital boundless capacity for speed and integration. It made good on one of these promises. Flows picked up speed and globalized and continue to do so to this day. Humanity, instead of being liberated by the emergence of digital technologies, has been forced to undergo a painful transformation to accommodate their proliferation in the workplace. Temporality veers wildly towards the unnatural and communication favors the simplistic as, “in the field of digital acceleration, more information means less meaning. In the sphere of the digital economy, the faster information circulates, the faster value is accumulated. But meaning slows down this process, as meaning needs time to be produced and to be elaborated and understood. So the acceleration of the info-flow implies an elimination of meaning.” Berardi describes this transformation as a paradigmatic shift at the level of social relations (and perhaps even at the level of biology), away from earthly conjunction and towards a synthetic connectivity, asserting that, “the leading factor of this change is the insertion of the electronic in the organic.” He elaborates:

“The spreading of the connective modality in social life (the network) creates the condition of an anthropological shift that we cannot yet fully understand. This shift involves a mutation of the conscious organism: in order to make the conscious organism compatible with the connective machine, its cognitive system has to be reformatted. Conscious and sensitive organisms are thus being subjected to a process of mutation that involves the faculties of attention, processing, decision, and expression. Info-flows have to be accelerated, and connective capacity has to be empowered, in order to comply with the recombinant technology of the global net… connection entails a simple effect of machinic functionality… In order for connection to be possible, segments must be linguistically compatible. Connection requires a prior process whereby elements that need to connect are made compatible.”

This change in us happened gradually, perhaps before a personal computer ever entered a private residence. In fact, corporate strategists came to favor a “networked” management structure long before the literal network ever came online. As I have suggested above, the submission of the world’s populations to the violence of debt helped inaugurate and later enforce this transformation in us. This technobiological evolution, this digital mutilation we are undergoing, represents the most serious threat to the ties that constitute us. Whereas ideology functions merely as a denial and a mystification of our ties and debt serves to corrode and corrupt our ties, the rise of digital technology amounts to a direct attack on the bodies sustaining our ties. Computing technology threatens to completely obliterate our capacity for empathy and solidarity, disintegrates our ability to conjoin, and dissolves our awareness of the sensuous: the lifeblood of our interconstitution, the source of our humanity. Berardi explains that, “In order to efficiently interact with the connective environment, the conscious and sensitive organism starts to suppress to a certain degree what we call sensibility… i.e. the ability to interpret and understand what cannot be expressed in verbal or digital signs.” Our language narrows, our horizons darken, social order breaks down and meaning gives way to chaos. Sensuous conjunction becomes networked connection, singularity becomes compatibility, and poetry becomes a glitch.

This inability to conjunct, this physical denial of our mutual ties, this loss of the sensuous and the natural, affects us on the level of meaning. It manifests itself as a ghostly trauma. We are haunted by the deep pain of the spectral loss of that which we were never able to clearly distinguish, its form only evident in a wavelength of light just beyond our eye’s ability to perceive. We feel the vague weight of our ties to one another only as an atmospheric depression, a potentiality foreclosed upon, now only existing as a lost reality, a sad fantasy of a life with others. This great lack is one potential starting point from which we can begin to retrace our lost ties and construct some semblance of meaning in this global superstorm of swirling info-chaos. Franco Berardi says as much in his 2017 book entitled Futurability, articulating that,

“pain forces us to look for an order to the world that we cannot find, because it does not exist. But this craving for order does exist: it is the incentive to build a bridge across the abyss of entropy, a bridge between different singular minds. From this conjunction, the meaning of the world is evoked and enacted: shared semiosis, breathing in consonance. The condition of the groundless construction of meaning is friendship. The only coherence of the world resides in sharing the act of projecting meaning: cooperation between agents of enunciation. When friendship dissolves, when solidarity is banned and individuals stay alone and face the darkness of matter in isolation, then reality turns back into chaos and the coherence of the social environment is reduced to the enforcement of the obsessional act of identification.”

Friendship is a prerequisite of meaning and thus a necessary precondition for the revolutionary sloughing off of the mummified husk of capitalist production. But friendship is impossible in an environment of distrust, cynicism, and bad faith. It follows that our immediate goal must be the careful fostering of those preconditions of friendship, the nurturing of an environment of trust and good faith, the development of an ecology of love. Our high level of cognitive connectivity could present an opportunity, but only as long as that connectivity is then able to be elaborated into actual bodily solidarity. Anything short of that is counterrevolutionary. The question we now turn to is one of action: how can we overcome the logic of finance and debt to reactivate our dormant sensibility and the inherent power in friendship? Is there a way of circumnavigating or outright obliterating the ideological, economic, and technological barriers to our coming together, our joyous re-union? And can sustained cultivation of the aforementioned preconditions of friendship result in a lasting apprehension of our ties to one another and the ensuing resurgence of the political and the possible?

Loving Giving So far, we have seen how the development of neoliberal capitalism and its associated technologies has functioned to rob us of our humanity, our interconstitution and intervitality; how it denies and openly attacks our ties to one another, and how, unchecked, it may transform us physiologically beyond any ability to return, where there is no longer a me-you and a you-me, but a you and a me that does not meet and mix; solitary confinement perfected. By reading Fisher, Lazzarato, and Berardi, we have identified three dominant fields of battle upon which our submission to the imperatives of capital is violently coerced and our capacity for struggle dismantled: ideology, debt, and technology. This multi-front assault upon the human and all of life is absolutely cause for despair, but is strangely also a reason for hope and a source of conviction in our practice. The immense amount of violence required to enforce the barbaric competition they call “order” is not evidence of its strength; it’s evidence of its weakness. As long as this war rages, our ties remain and another world is still possible. The day our compliance no longer requires immense ideological and psychological operations, a boundless debt prison, violent repression, and a painful, pharmacological and physiological transformation and integration into the digitized flows of capital is the day all is lost. But their war of all against all rages on and we remain human against all odds. “Life finds a way” – for now.

Technofinancial power cannot seem to stamp out the humanistic drive towards radical acts of insolvency, trust, and selflessness, even though sadly much of this drive is channeled towards frantic crisis response, trying to mitigate the damage of our system’s greatest excesses (feeding the unfed, housing and caring for the unhoused, legal support for the persecuted, etc). Even capital has, up until this point, been forced to cloak its domination in philanthropy. This is why all of the world’s arms manufacturers and pharmaceutical barons are such virulent “supporters of the arts.” But the masks are falling off and the hour grows late for our planet. Gramsci said, “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born, in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” A popular, and ultimately useful, mistranslation of the quote concludes ominously: “Now is the time of monsters.” And if the last decade has proven anything, it’s that the only hero we can count on is each other. Every one of us has the capacity and the duty to be both doula of the new world and vanquisher of the old one, and our salvation depends on the generalization of a hero’s bravery...

What happens to us when we share or give? Why can’t we seem to shake the old habit of altruism despite it’s utter irrationality under a system whose basic incentive structure rewards the opposite? We remain social animals despite our being governed by an antisocial ideology and we still desire love and communion despite being forcibly transformed into unfeeling, unsleeping computer parts in the automated circulation of symbols.

Giving is the main idea I want to bring forward for discussion here. It must first be said that not all giving is equal, neither in its material impact for the receiver nor in its ability to call forth our bonds from the shadows and into the warm light of apprehension. Certain acts of giving may provide immense material support for the receiver, but do little to reaffirm our ties to one another, our interconstitution, thereby unintentionally softening the brutality of capitalist production while leaving our political obligations to one another unelucidated. Whereas other acts of giving may do the opposite: forcefully affirm our ties but offer little in the way of material support, likely a key component of any act of giving that seeks to create the necessary space in the receiver’s life for proper politicization. A balance must clearly be struck, and can likely only be found through rapid and widespread experimentation, buttressed by solid theoretical and historical analysis and reflection. There also exists another type of giving, a giving that is not giving. You know this type of giving, as it is everywhere: the type of giving that asks for something in return; the type that reduces giving to an exchange; the type that requires a promise on the part of the receiver; conditional giving. This is not giving, but debt in disguise, and it must be opposed without reservation.

Already, we can begin to see the faint outline of the type of action that has potential utility in our pursuit of another world. Firstly and most importantly, giving that asks nothing in return. Giving freely and unconditionally. We can call this type of giving, loving giving. Loving giving, as opposed to conditional giving, is an act of faith and of prefiguration (of course, with varied degrees of effectiveness and vibrational intensity). It is a negation of competitive ideology, a refutation of debts logic of solvency and personal responsibility, and a rejection of the inorganic and the virtual in favor of the organic and the natural (“a century ago, scarcity had to be endured; today, it has to be enforced”). Beyond that, loving giving can be said to act as a positive affirmation of our precarity, of our shared condition and interests, and our interdependence on each other for the propagation of human life. Judith Butler makes clear that,

“...each of us is constituted politically in part by virtue of the social vulnerability of our bodies- as a site of desire and physical vulnerability, as the site of a publicity at once assertive and exposed. Loss and vulnerability seem to follow from our being socially constituted bodies, attached to others, at risk of losing those attachments, exposed to others, at risk of violence by virtue of that exposure.”

We are political creatures because of our exposure and vulnerability to each other. We are threatened by each other constantly, yet made by each other perpetually. In this way, an act of loving giving is always underwritten by the threat of violence, our looming death, perhaps at the hands of another. Death is the third party to any act of giving; violence is the notary of all love.

When we give lovingly, recklessly, irresponsibly, insolvently, and in good faith (without condition, without narcissistic recognition), the act is defined and given its shape by the other choice, the path not taken: the choice to take as much as you can get, to harm, to ask for something in return. Under neoliberalism, even ostensible inaction amounts to the de facto submission to capitalist logics. We’ve already seen how debt paralyzes us with its myopic obsession with solvency. Austerity, in some ways, can be understood as an act of inaction. There is no neutral, not anymore. There likely never was. You can act with love and bravery or you can (in)act with fear and violence. When we act in love, we create an us, and every us is predicated by an exterior, often hostile: nature, scarcity, industrialists, colonial forces, American imperialism, those who would rather we not give, that we instead sell and buy, that we exploit each other to get what we need to survive. The act of giving, then, is also an act of revelation. Giving makes sense of the world for the involved parties. It illuminates our status as both victims of a great theft and makes clear our reciprocal responsibility for maintaining the conditions where life can flourish, that we are equally culpable co-authors of our own existence. This re-establishing of our apprehension of our being bound up in one another is a precondition for any movement against the present state of things and towards anything close to communism. Acts of good faith, of loving giving, artfully designed to undercut forces of control and alienation, to debunk competitive ideology, to dismantle logics of debt, and to negate our subsumption to the digital, carve out the revolutionary us by establishing a hostile exterior and simultaneously create an atmosphere in which trust and friendship can flourish, where a return to the sensuous and to each other is possible: an ecology of solidarity and of love.

Without a doubt, it will absolutely take much more than acts of loving giving to overthrow capitalism. The importance of a diversity of tactics has been theorized for far longer than I have lived. In that spirit, I feel I must make special emphasis of the fact that during the aforementioned George Floyd riots in late May, all of the bad faith, mistrust, selfishness, and suspicion of one another was instantaneously, albeit fleetingly, abolished. Solidarity was revealed among total strangers, power erupted between and within us. Our ties to one another, despite our obvious differences (race, neighborhood, class), emerged with astounding clarity and the role of the state in enforcing capitalist relations could not have been made more plain to everyone downtown that day. Challenging police power, refusing to disperse, asserting our right to mourn as well as our willingness to get beat up, gassed, arrested, or worse (to give all?) in order to do so, risking social insolvency or financial devastation for a chance at communion, these are forceful enunciations of our intervitality, acts of love and of life and of faith that bring our bonds into focus, as well as sharply delineating the hostile forces opposing an emergent us.

With this, at last, we return to our original question with something approaching an answer: can we bring our constitutive ties up to the level of naked visibility without relying on the reactive transformational process of mourning? We would say, “yes.*” We’ve now seen how acts of loving giving can be used to assert our latent bonds to one another and reawaken a dormant solidarity and power. It can also be said that loving giving undercuts the entire chain of valorization and contains a vestigial communal logic, on top of prefiguring a world of abundance and cooperation. My utopian heart yearns to proclaim this to be one of the many possible modes of proactively attacking capitalist relations laid out before us, but as is usually the case in this type of thinking, it is more complicated than that. It must be noted that loving giving only contains such potential usefulness for our cause because it is predicated on the great historical and ongoing theft occurring all around us. The theft of our spirit, our ideas and inventiveness, our bodily energy and our human potential, our mortal life and the content of our dreams, and of our ability to reproduce ourselves in harmony with each other and with nature. In this way, it too is a reaction to a great loss. Loving giving only rings out with such piercing resonance in a world of theft and isolation. It follows that our righteous attack on capitalist relations in the form of loving giving is in fact an expression of mourning; it is our grieving the world that could be.

Good Faith and Song Maybe it is impossible to avoid mourning in our search of a politics that can bring us towards another, better world. Perhaps it is best not to run from our loss, for we have lost a lot and lose more every day. In a world literally founded upon mass theft and slaughter, maybe it is indeed the most materialist site upon which to build something new. Our collective loss is perhaps one of the few remaining things we truly share in a world devoted to the accumulation of difference and distinction. Though, in these parting words, I want to also suggest that these differences and distinctions between us need not be a source of division and that the way forward may not necessarily entail the submission of the singular to the collective. One month has passed since the George Floyd riots of May-June and a process of division, repression, and recuperation has largely played itself out. Save for a select few city centers (and bravo to them), the fires have been doused and the barricades have been removed. The rowdy, “problematic” elements comprising the protests leading edge have largely been held back or outright turned over to the authorities and despite the rather astonishingly measured criticisms of criminal property destruction, the practice has broadly been replaced by more “respectable” forms of protest. The role bad faith has played in the apparent quelling of righteous rebellion cannot be understated. With the exception, apparently, of Portland, Oregon, the capitalist state did not require its superior military technology nor a COINTELPRO level conspiracy (although I’m sure we will learn much in the decades to come about how government agencies managed the flows of information on social media) to bring this uprising to its knees. The bad faith of debt society acts to ensure our governability. Control is smuggled into our minds by the trojan horse of opportunity which is then invaded and colonized by the forces of debt. One of the first tasks for us then must be the supplanting of the system’s bad faith with our forceful good faith. Many have already begun work on this urgent adjustment. Evidence of this can be found in the internationally adopted protest slogan “no good cops, no bad protestors.” And as long as the fighting continues somewhere, presently in Portland and perhaps Atlanta, the spark of uprising still dances in the winds of this world’s chaos and all remains possible.

With these final lines, I hope to clarify how exactly we can characterize this good faith and trace what it could look like in practice. As I have hinted at above, the good faith this moment requires is not that which requires some type of submission to a preformatted gestalt. It is not the good faith of brotherhood or family, nor is it the good faith of a party or an army. What is needed is a unique form of good faith that embraces difference, that leverages our irreducible singularity towards a collective end. If we are indeed to strum and pluck at our ties to one another, revealing and (re)politicizing our interconstitution and forging a new rhythm by which we ascribe our lives new meaning, we will need the type of trust found only among a group of musicians, the good faith of a band. A band’s members develop a sense of faith in one another that does not necessarily depend upon adherence to a set program or a uniform skillset. When one member improvises, they are trusting the others to keep rhythm. This good faith must flow in both directions. At the same time, the other band members must be able to trust that the improvisation of the first musician will not ultimately lead the group beyond an unsalvageable point of no return or to a place that jeopardizes the entire performance. We have seen a very similar dialectic play out in the last few months of protest. Peaceful marches go nowhere without the militant, sometimes violent, radical edge to push things forwards, applying pressure and teasing out the contradictions of our system. Likewise, the most radical elements of a protest are easily isolated, villainized, and violently squashed without the cover and legitimacy of the less radical masses. This is a delicate balance, and it will not be struck every time. Someone hits a bad note, someone reaches for a spectacular flourish but doesn’t cleanly play it; this happens with the most seasoned and well rehearsed performers and it undoubtedly will happen in our novice first attempts at creating music together. Mistakes are relatively unimportant. What is important is what happens after. Do we stand by one another, trusting that our partners are doing what they believe right as best they can? Or do we point fingers, stop playing, and allow our efforts to disintegrate so as to avoid being lumped in with a “bad musician?” We only need to look at the last few months of unrest in this country to see that the latter spells disaster and unstoppable fascism.

A comrade asked me while looking over my shoulder as I write these parting words, “what is the nature of the song we are writing? How does it sound and what is it about?” I’ve been thinking about how best to respond to this, especially as I sit somewhat aghast at the anarchy in the above paragraphs, written by an ostensible communist. Here I must solely rely on my much deeper personal experience as an actual musician literally playing music with friends than on my limited theoretical capacity and relatively amateurish abilities as a writer and worse still, thinker. In this light, the answer emerges immediately: at this beginning stage, when we are just now learning how to play our respective instruments, albeit in a condition of extreme urgency, it does not yet matter. What is important is that we play, and play together, often, and with a spirit of openness and experimentation; building trust and solidarity and good faith and friendship while honing our respective skills, finding our specialized roles in a revolutionary assemblage. It is only in this playing together that a common taste and interest can emerge. Deciding on a rhythm or a theme for a project before ever getting into a room together to play would unquestionably be putting the cart before the horse and in the same way, thinking up a program or adopting a party line would be premature if it is not done in the context of an already ongoing collaborative struggle. We cannot yet know what new rhythms of living and sources of meaning await our discovery and pretending as if we do could actually preclude us from ever arriving at a song truly worthy of us and our respective dreams and desires. Until that time, we must begin to do the mystical, patient work of fostering the conditions for a blooming solidarity, incubating trust and friendship, meticulously cultivating an ecology of love. For love is the energy with which the ties between us vibrate. With practice, this vibration can be bent into a tone, in time and as our power multiplies, a tone becomes a chord and then, a phrase, and one day, a song will erupt forth from the space between us and all that’s within us, unmistakable and unending, and with that song will come a new rhythm to move through the world to. With practice, good faith, and determination the day will come when our music has filled the air and all that remains on earth for us to do is dance together and fall into love. Inshallah.

“Music is a peculiar mode of chaosmosis: the osmotic process of transforming chaos into harmony. Music’s process of signification is based on directly shaping the listener’s body-mind: music is psychedelic (meaning, etymologically, “mind-manifesting”). Music deploys in time, yet the reverse is also true: making music is the act of projecting time, of interknitting perceptions of time. Rhythm is the mental elaboration of time, the common code that links time perception and time projection.” -Franco Bifo Berardi

“Some thoughts have a certain sound, that being the equivalent to a form. Through sound and motion, you will be able to paralyze nerves, shatter bones, set fires, suffocate an enemy or burst his organs.” -Paul Mu’adib in David Lynch’s Dune (1984)

0 notes

Text

Letter to Mr. Gansa

Dear Mr. Gansa, I didn't want to write: my avoidance was vicious and unrelenting so I held onto it in desolation. I didn't want to tap into the incandescent fury and void of pain which always sits beneath the surface of the emotional kaleidoscope that is my life. Broken, shattered at the edges, spilling out in triggers to a skewed perception of where I am and who that person is. I had to quell the screaming taint of a disenchanted terror at the destruction and hollow, pointless discarding of a most beloved character by Homeland. I realized after I began I had been writing this letter in pieces with each tweet and observation on Quinn, on Homeland: how it had failed him, us, diminished an opportunity to recognize an unending ability in Rupert Friend or influence a societal preconception and view. I found Homeland in Season 1, searching for a gritty escape in entertainment that would provoke me intellectually and emotionally. Homeland was such a show, a view into the world of intelligence: a modern representation of an agency in action. I became an avid fan. I grew to anticipate impatiently every week when Carrie would appear and hurtle into her flawed, strong, onslaught into the world of the CIA. It became an integral part of my life and escape from the difficulties that hamper my days. I was intrigued when Quinn came into full view, his humble beginnings almost an aside to Carrie's bursting, frantic, headlong rush into a veiled intricate terrorist landscape. I didn't invest in Carrie, I admired her, was fascinated and mesmerized by the many layered facets to her character but I found her profoundly difficult to like. There was something missing, a part that was necessary to embrace her emotionally and I could only appreciate her in a reflective view. Quinn however sparked an intrigue, a difference, established himself as the centre of Homeland intrinsically with such composure and control. His emerging self reflection, morality and code showing his humanity which was rich and rewarding, in stark relief to those surrounding him, making their contribution seem devoid of any colour. Quinn became an essential investment and part of me so effortlessly where I felt every disappointment, every frustration, every conflict at his position. He reached out, emanating a security and substance that was reassuring and cohesive. I looked to him to lead the show, to hold the others together with quiet authority. I lived him as I have no other. It became a realization that Quinn would be the one to take me on his journey in Homeland, it would be his that I would stay with the show for. During Season 5 I didn't think it was possible to share so much torment or searing agony with Quinn, subtly nuanced in many ways, impactative to us all. Outrage overtook the pain at his unexpected demise. Rupert stunningly soliloquized a summation of Quinn's worth laid bare in a love letter to Carrie, writing in exception from his internal scope of an actor understated in his representation of a Quinn shackled to a world of personal conflict, torment and regret. I was overjoyed Quinn returned in season 6 and he was a revelation. Rupert's gift of a soldier in such beautiful humanity, such depth and such compassion connected on so many visceral levels, it left me breathless, projecting an emotional warmth which was all consuming: his internal reach in his ability was astounding leaving me choking in an unexpected resonance. Having suffered similarly to the character due to different experiences, it was almost frightening to see him take a collective anguish and furious shame and hold it up to the light of social acceptance and scrutiny, to display this brokenness in an unapologetic exceptional manner, confront a discomfort and avoidance so prevalent for those who suffer, through a character so many had come to love wholeheartedly, hold close to them in almost abhorrent comfort at his continued torture and destruction. I found myself shouting at the screen, moved beyond tears where he invoked a myriad of shared emotions and experiences. It was disorientating, affirming, an exquisite recognition of a splintered soul. As Quinn continued to be targeted, broken down, and suffer without necessity or aim and glimpses of his torturous past arose with unrepentant venom, Homeland left me gasping, struggling to find a sensibility in it or any proper address to the abuse. These revelations and ongoing torment alienated me from the rest of the show, bar Quinn, where the almost gleeful shades of competitive harm to him became derisive, farcical, undermining those abuses into frivolity. During the season Quinn's range grew and I didn't know where he ended and I began. I have PTSD and head trauma and it destroyed me, devoured who I was, spewing out an unrecognizable enemy I couldn't befriend. Belief in kindness or those qualities that shine a light in the world as individuals or as a collective as intrinsically good was gone replaced by suffering, crippling fear and threats everywhere. Any state of grace or semblance of peace was elusive. I was considerably more invisible than any VET, because my damage wasn't borne of a higher purpose, there was no sense to my fracture, no overriding objective to my pain and altered awareness. Quinn inspired my damage to hope, lifted me to where worth had a place, voiced my horror in eloquence, provoked overwhelming love in a character entrenched in mine and the audience's reality, lives & beings. Quinn's thoughtless end was a martyr rhetoric, almost as if you didn't know how to discard him, an afterthought. How Quinn died was glorified in a cheap and hollow accolade of the shows desperation to sell their idea of relevance: to sell the agony of grief to the highest bidder. Rupert Friend gave all of himself to create something of merit, worthwhile, entrancing: a gift to the audience and fans in tribute to those he portrayed in his generosity of talent. His senseless destruction defiled that, insulting everyone who had a connection to Quinn or who saw him and found inflections of themselves within a platform and character they loved. The audience's invested humanity to Quinn was ridiculed because how he died was immortalized as a tribute, with no recognition or celebration for how he lived. He was dismissed, forgotten, consigned to rubbish: his sum worth the self involved lamenting of Carrie Mathison. Quinn was a representation of profound and copious parts of the human condition: so many of those forgotten, overlooked and damaged: his treatment and demise dishonoured that demographic irrevocably. He did not die a hero, he died a victim of an agency and show who slaughtered him for political strategy, for an in house fight for supremacy, for their own individual agenda's and ego's. Not in war, not for a populace's safety and fundamental freedoms: a tortured statistic who had outlived his usefulness, a number, a completed sentence on a page. Unforgivable. Intolerable. Sacrilegious. Homeland had an opportunity 'to effect real change' without any intention to utilize it despite their reach and ability to make political comment or offer significant influence. A platform to transform the narrative, perspective and conversations. Quinn's treatment was repugnant. He died in emptiness, in darkness, in torment by his own comrades, murdered without any chance at redemption, hope or having any belief he was valued or loved. He was disposed of in contempt, a social commentary Homeland appear almost proud of. This short sighted indifference has contributed to the wreckage a demographic, already devastated by the reality of their existence, experiences. The show felt they had permission to treat Quinn with a disrespectful inevitability, a mocking testament to how Quinn's representation was held in so little regard. Rupert Friend evoked a connection and love for a character that grew with each season until he became inexorably entwined, grew within my emotional self and inspired an acceptance, an abundance, which I will never let go of. His ability to provoke such a yearning empathy and identified humanity is a testament to his emotional range and brilliance. I will be forever grateful I joined him on his journey of revealing Quinn for who he became, which has become an esoteric part of me, because everything I cherished about Quinn ,Homeland took and smeared with empty indifference, ignorance, sullied it with disillusionment and scorn. Whilst you, colleagues and some media have derided, demeaned and belittled fans for their reaction to Quinn's demise and appalled rejection of your vacuous ever shifting explanations and too late platitudes, the fans recognize Quinn was far more than a character, had considerable impact above the show's story lines, was larger and more important by his delivery than the dismissive responses you gave and therefore care enough to protest that disservice to him, to those already fallen in war and left to fall once home, to the far reaching consequences of your inconsiderate squandering of Quinn. Goodbye Homeland. I have your trash bag waiting. - @badfluff on Twitter