#she's also ainu and okinawan

Text

The Midoriya-Todoroki Family (+Ochaco and Tenya) in this picrew!

In order left to right, top to bottom: Inko, Rei, Touya, Natsuo, Fuyumi, Izuku, Shoto, Uraraka Ochaco, and Iida Tenya!

@afrolatinozuko

#inko midoriya#rei todoroki#touya todoroki#fuyumi todoroki#natsuo todoroki#izuku midoriya#shoto todoroki#ochaco uraraka#tenya iida#beta israel midoriya agenda#bangleshi rei agenda#kochinim iida agenda#beta israel uraraka agenda#she's also ainu and okinawan#picrew#rei x inko#i forgot their ship name L for me

66 notes

·

View notes

Note

ty for the compliment i really appreciate it 🐕 anon and mod ^.^

here me out. shiho really likes learning native tribal languages (??? I’m 50% sure that’s the name but idk if it’s correct, im sorry if i offend anyone)

some languages i think she picked up would be:

ainu itak

cherokee

okinawan

hopi

lakota

also i see her speaking french or german for some reason

-language anon

.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

i genuinely think that misa would've tried to use her platform for humanitarian causes. yes, she's the second kira & yes, she's a serial killer & a mass murderer, but she firmly believes in justice & helping other people & only punishes people who do, like, really awful horrible shit like child abusers, animal abusers, sex offenders, traffickers, people who abuse sex workers, people who beat their spouses, corrupt government officials, especially those who explicitly makes laws against marginalized groups, people who've done racist, homophobic, transphobic or otherwise queerphobic, ableist & religious hatecrimes, in self defense to protect herself, to protect people she cares about & loves or to avenge herself when she's wronged. especially because her own government & her justice system wasn't there for her.

misa was very well loved & her fanbase is entirely aware of her traumatic background which is why they ride so hard for her. i genuinely think that she'd use her fame, influence, & platform to raise awareness about important social, environmental & humanitarian issues & gives back to various charities, particularly queer people bc i think she'd publicly come out as bisexual which would likely shock a lot of people as while there's not as much moral or social weight to orientation or gender as the west, the government of japan is relatively conservative & thus people who're members of the LGBTQIA+/queer community in japan still face significant discrimination & prejudice to the point where it's hard for many people to come out, same gender marriage & same gender couples can't legally adopt children still isn't a thing over there but misa doesn't give a shit & keeps advocating for queer people locally & internationally, sex workers rights considering she was one herself, supporting the education of young women, & community growth both locally & internationally by supporting people who were wrongfully detained & tortured, domestic violence survivors who often go unreported due to social & cultural concerns about shaming the family name, homeless people, refugees & displaced peoples & their families & advocating for mental health, animals & giving knowledge to outcast animals that have been neglected, mistreated & misunderstood, supporting minorities in both japan like with the hisabetsu-buraku, the descendants of outcast communities of feudal japan, the ainu & okinawans (whom she also shares heritage with. btw), the indigenous peoples of northern & southern japan respectively & gaikokujin / foreigners & non-japanese people in the country & internationally & helping the environment & promoting diversity in the beauty & fashion industry because she's the type of person to do that, she's literally around a shinigami constantly 24/7 & doesn't blink an eye, & pays visits in hospitals including children's hospitals & spending time with them especially because she has a soft spot for children because she wanted to be a mother herself eventually, & sends a lot of her money to relief funds when natural disasters strike both in japan & other places around the world. bc like. yeah misa is morally questionable in the sense that she's an international star & a model & an idol secretly moonlighting as the second kira but her heart is in the right place.

0 notes

Note

In a modern AU where most of the cast is not originally from Alaska, where do you think they'd be from?

I don't know, I've seen people from just about every irl cultural inspiration for the show in Fairbanks (except maybe folks from Tibet, but I never actually asked so), the majority of them living there with their family and still speaking their languages, so I never really thought about back stories where everyone 20 and younger wasn't simultaneously born in Alaska and still being raised in a non-American culture. It never occured to me that was something I might need to do. Alaska is ridiculously diverse and no one ever talks about it.

I guess I do have cultural backgrounds, so I guess that could be where they're from? I dunno if that counts though.

Sokka and Katara's family is always Bering Straits Inupiaq. Exactly which village they're from isn't always specified (honestly just assume King Island unless stated otherwise because I like to be important), but they typically have family in nome.

I haven't written much with Aang, but I end up conceptualixing him as Thai a lot because most Buddhists I've seen were Thai. I should probably put more effort into thinking of him as Tibetan.

Ozai and Iroh are Chinese and Ursa is Okinawan with family in Hawai'i. One idea i keep getting is Zuko saying he's Japanese on his mom's side and when someone brings up that he said his mom is Okinawan he says "My dad says it's the same thing."

Suki is Ainu and Siberian Yup'ik

Toph is Chinese and depending on the day you ask, she was either taught English along with Mandarin Chinese by her bilingual nanny or learned English exclusively from Mel Brooks movies she technically wasn't allowed to watch. She also speaks French and Hebrew, claiming "I just like the way they sound."

Haru is Korean and Haida. The parents he refers to are technically his aunt and uncle on the Korean side, but as they can't have kids and he's been in their care for as long as he can remember, they're Mom and Dad to him. He has plenty of contact with his Haida relatives and there's a lot of planning ahead so that he has equal exposure to each culture.

Jet is Koyukon, Gwitchin, and Tanana, though he doesn't know how much of each.

Might add more at a later date

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Other envisioned in Disney's Pocahontas (and Pocahontas II) is characterized by typical symbols of difference—backwardness—which is coded largely in the representation of Native Americans. This style of depiction potentially invokes what Rey Chow calls 'a phantom history' (1993: 37), by which Western cultural critics tend to turn the native (intentionally or unintentionally) into an object that is manageable and comforting through the manipulation of history. That is, the static Other remains frozen as a specimen, while the privileged Self keeps developing as time progresses. This concept illustrates a way in which a problematic notion of time lag between civilized whites and backward Native Americans is highlighted to serve white critics' (Self) appetite for consuming the Other. This process of Self/Other demarcation emphasizes that history brought into the present enables white ethnocentrism to re-establish superiority in relation to the imaginary Other. That is, historical setting can provide the perfect site for the dominant power to reinstate what Said calls 'imaginative geography' (Said, 1995: 54), which upholds the myth of the timeless native Other and illuminates the progression of the Anglosphere.

[...] While Pocahontas is inclined to induce interpretations based on dichotomous perspectives, by designating the Powhatan as the Other and the settlers as Self, Mononoke highlights the existence of multiple Others in Japanese society. This representation of otherness challenges the dichotomous concept of Self and Other, as well as subverting the myth of the Japanese as a homogenous nation. In Mononoke, all characters except Lord Asano (who is only mentioned when his samurai briefly appear) and the emperor come from various groups of Others in society. It is these Others that move the narrative forward.

For instance, Ashitaka is from the ethnic group known as the Emishi—a clan that fought against the Yamato regime and was marginalized to the Northeastern parts of the country. From the seventh to the thirteenth century, the central government treated the Emishi as an uncivilized ethnic other, or an abject. The narrative of Mononoke foregrounds this marginalized clan (or the Other) while the Yamato Imperial Court (the central government) —the alleged Self—is hardly involved in the narrative. The central government is mentioned in characters' conversations, but the film's plot predominantly revolves around social Others, including the Emishi, San, the wild woman in the forest, and those whom Lady Eboshi hires in the iron-town—prostitutes and lepers. This evokes the current population of Japan as a composite of differences and conflicting values that includes the Yamato, Ainu, and Okinawan peoples, as well as zainichi Koreans (Korean permanent residents in Japan). It is indeed a historical fact that stretching back several hundreds of years, various races and ethnicities, including Asians and Oceanians, have moved into Japan, and at the time that the Emishi existed, Japan was such a racial melting-pot (Kuji, 1997: 78-80).

[...] Relating to the multiplicity of otherness, the interactions between different groups demonstrated in Mononoke are not likely to induce the notion of 'abjection' by which one excludes outsiders/others to secure boundaries separating them from one's own group. That is, identity recognition for each group in Mononoke is not accomplished by exclusion or assimilation, but through a dialectical process of blurring the lines that mark differences. The boundary blurring is intensely envisioned in the iron town—a carnivalesque site—where marginalized Others and the 'abject' are empowered. In this site, no authority figure is identified, and therefore there is no single power pushing the narrative forward.

This manifestation of the iron town evokes Bhabha's (1994) concept of space 'in-between'; a space that destabilizes dichotomous patterns of identity formation with hybrid identities and allows for a new subject to emerge. This space is specifically exemplified by three main figures: Ashitaka, San, and Eboshi. These three characters signify the ambiguity of identity categorizations: mainly in the blurring of the line between nature (spirits and animals) and culture (humans and civilization). San—a combination of princess and mononoke (a possessing spirit)—symbolizes a liminal space between nature and culture. San is biologically human, despite her wild disguise with a wolf-pelt shawl and spear to perform as an Other—she tells Ashitaka, 'I am a wolf.' Thus, her identity does not conform entirely to humankind or to nature.

Eboshi's characterization is also transgressive. On the one hand, she is a typical industrialist and rationalist; on the other hand, she is also attached to the uncivilized Other, drawn together from several historical character types. Image analyst Kano Seiji describes Eboshi as a daughter of the Shimazu clan who is forced to marry a daimyo (feudal lord) and resists her husband, which then leads her to being sold to become a prostitute (yujo), until finally she is taken by the head of a Japanese pirate group (wako) whom she eventually kills (Kuji, 1997: 73). The depiction of Eboshi as the head of pirates and a murderer underscores her ruthless and cruel persona, which aligns with her other side as the calm and rational leader of the iron-town.

Likewise, Ashitaka is biologically human, but as he becomes possessed by a curse, his body is invaded by a mononoke, symbolic of an abject other. In other words, his identity is a hybrid of his original self and a foreign other. He thus lies somewhere between human/civilization and the forest where mononoke exist. The notion of abject manifested in Ashitaka's body is slightly different from Kristeva's (1982) 'abject' that refers to a part that needs to be rejected for establishing one's identity. Instead, Ashitaka's abjection represents a part that is never completely removed from his self, but lives with him to complete his identity. In this respect, in-between-ness presented through Mononoke disrupts the notion of Self/Other itself, rather than simply inverting positions between Self and Other.

National Identity (Re)Construction in Japanese and American Animated Film: Self and Other Representation in Pocahontas and Princess Mononoke by Kaori Yoshida

#hayao miyazaki#princess mononoke#readings#quotes#wanted to read a piece abt princess mononoke & this was good

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

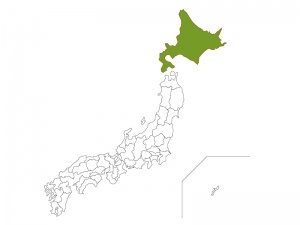

Moderately Interesting Japanese Ep. 8 Hokkaido Dialect

The typical winter scenery of Hokkaido.

One of my favorite aspects of language learning is studying dialects. I am fascinated by how language branches and adapts to new environments like some form of linguistic natural selection. Japanese is rife with interesting dialects, some of which are so different from the standard that they can sound like a totally different language to the untrained ear. I thought I’d make a series of posts highlighting different dialects in Japanese. Since this sort of post will take a bit more research on my end and I plan to find native speakers of the dialect to confirm with, they won’t be very regular, but I hope that you enjoy them!

What are some of the main Japanese dialects?

Firstly, let me tell you how to say “dialect” in Japanese, because I know I’m gonna use it and I don’t want to cause any confusion.

方言 (hougen)

Dialect

___弁 (__-ben)

__ Dialect, so “Osaka Dialect” is “Osaka-ben.”

I daresay that just about 100% of all Japanese learners are familiar with Tokyo-ben, because it is Standard Japanese. The next most popular dialect is Kansai-ben, which is spoken in the Kansai region (Osaka, Hiroshima, etc.). The Kansai Dialect can be broken down into several smaller, regional dialects. Next would probably be Okinawa-ben.

(Caution! Some people, particularly Okinawans, consider Okinawan Japanese to be a language independent from Japanese, and they can be offended if you refer to it as a dialect. Japan’s official stance is that Okinawan is a dialect, though, so I am calling it a dialect in my posts.)

Now without further ado, let’s actually start learning about one of these dialects!

Hokkaido-ben, namara ii!

Hokkaido is the island in green. It’s the biggest prefecture in Japan by far.

I am a foreigner and Japanese is not my native language, but I have been living on the island of Hokkaido for 5 years now and am very comfortable with the Hokkaido dialect, so I chose to introduce it to you first. Also, it’s not one that gets talked about a lot, so I figured maybe there weren’t many posts about it.

Hokkaido is the northernmost island of Japan, and it wasn’t settled and officially incorporated as part of Japan until the late 1800′s. There is a group of indigenous people here called the Ainu who speak a language completely different from Japanese, but their language has not bled into Hokkaido-ben. (Many place names in Hokkaido are from Ainu, though).

Because Hokkaido was settled so late in history compared to the other islands of Japan, their dialect doesn’t differ drastically from Tokyo-ben. There are some minor intonation differences that, frankly, I don’t feel confident explaining. I have internalized the intonations through exposure, but I’ve never been taught it and don’t really know what is correct. So I’m not going to talk about tonal differences, and instead focus on the different words and a wee bit of grammar.

投げる Nageru

Standard Japanese: 捨てる suteru

English: to dispose of (lit. “to throw/toss”)

To an English speaker, “throw away” feels just as natural as “dispose of.” But to people outside of Hokkaido, it sounds very unusual and the image it conjures is comedic, like someone is hurling trash into the garbage can like it’s the opening pitch at the World Series.

Example: そこの古い新聞を投げていいよ。

Romaji: Soko no furui shinbun wo nagete ii yo.

Standard: そこの古い新聞を捨てていいよ。

Romaji: Soko no furui shinbun wo sutete ii yo.

English: You can throw away those old newspapers there.

おっかない Okkanai

Standard: 危ない abunai

English: dangerous, scary, a “close call”

My hostmom uses this with me, like, all the time. According to her, I’m always doing okkanai things, like walking alone at night or *gasp* going outside with wet hair. I love her so much haha.

Example: うちの子が熊のぬいぐるみだと思って遊んでいたのは本当の子グマだった。おっかなかったわ!

Romaji: Uchi no ko ga kuma no nuigurumi da to omotte asonde ita noha hontou no koguma datta. Okkanakatta wa!

Standard: うちの子が熊のぬいぐるみだと思って遊んでいたのは本当の子グマだった。危なかったわ!

Romaji: Uchi no ko ga kuma no nuigurumi da to omotte asonde ita noha hontou no koguma datta. Abunakatta wa!

English: Our kid thought he was playing with a teddy bear, but it was actually a live bear cub. What a close call!

(手袋を)履く (Tebukuro wo) haku

Standard:(手袋を)はめる (tebukuro wo) hameru

English: to put on (gloves)

Winter in Hokkaido is long and cold. Gloves are one of the most essential articles of clothing here, and I have heard/used “haku” so much that “hameru” sounds incorrect to me. The “haku” sounds funny to other Japanese people because it is used for putting on socks, underwear, and pants, and they will imagine you putting socks or panties on your hands instead of gloves.

Example: 外は寒いから、手袋を履きなさい。

Romaji: Soto ha samui kara, tebukuro wo hakinasai.

Standard: 外は寒いから、手袋をはめなさい。

Romaji: Soto ha samui kara, tebukuro wo hamenasai.

English: It’s cold out, so put on your gloves.

めんこい Menkoi

Standard Japanese: 可愛い kawaii

English: cute

I included this because it’s one of the famous aspects of Hokkaido-ben, but I actually don’t hear it used that much. I tend to see it on souvenir shirts for tourists more than in actual conversations.

Example: この子猫はめっちゃめんこい!

Romaji: Kono koneko ha meccha menkoi!

Standard: この子猫はめっちゃかわいい!

Romaji: Kono koneko ha meccha kawaii!

English: This kitten is super cute!

Note: Even though it is functioning as an adjective and ends with an “i,” it is not an “i” adjective. It is a “na” adjective.

あずましくない Azumashikunai

Standard: 居心地が悪い、嫌 igokochi ga warui, iya

English: uncomfortable (surroundings), unpleasant

This is a word that many Hokkaido people use but struggle to explain. Azumashikunai describes any place that you find unpleasant or uncomfortable, maybe due to it being too crowded, or too empty, or because it’s very cramped, for example.

Example: 日曜日の札幌駅が人混みであずましくない。

Romaji. Nichiyoubi no Sapporo-eki ga hitogomi de azumashikunai.

Standard: 日曜日の札幌駅が人混みで嫌だ。

Romaji: Nichiyoubi no Sapporo-eki ga hitogomi de iya da.

English: Sapporo Station is always crowded on Sundays and I don’t like it.

いずい Izui

Standard: none

English: different (in a bad way), off-kilter, something is “off”

Hokkaido people really struggle to explain izui because Standard Japanese doesn’t have an equivalent for it, but I think it can be likened to “off” in English. You got something in your eye but can’t find it and your eye feels funny? Your eye is izui. You have a hair in your shirt and can’t find it? That feels izui. Sometimes it can be a mysterious ache not painful enough to warrant a visit to the doctor, or sometimes it can just be a sense that something is “off.”

Example: 目にゴミが入って、いずい。

Romaji: Me ni gomi ga haitte, izui.

Standard:目にゴミが入って、痛い。

Romaji: Me ni gomi ga haitte, itai.

English: Something got in my eye and now it feels off.

汽車 Kisha

Standard: 電車 densha

English: (train, lit. “steam engine”)

The first time I came to Japan, I could just barely hold down an everyday conversation in Japanese. My hostparents (hostdad especially) both spoke very strong Hokkaido-ben, and during my first meal with them my hostdad asked if I had traveled from the airport to their city by “steam engine,” and I was just baffled. Wait, did he just say locomotive? What year is it? Are steam engines still a thing in Japan?! Then my kind hostmother explained that he meant regular, modern trains.

Example: すみません、函館ゆきの汽車はいつ出発しますか?

Romaji: Sumimasen, Hakodate-yuki no kisha ha itsu shuppatsu shimasu ka?

Standard: すみません、函館ゆきの電車はいつ出発しますか?

Romaji: Sumimsaen, Hakodate-yuki no densha ha itsu shuppatsu shimasuka?

English: Excuse me, when does the train bound for Hakodate leave the station?

しゃっこい Shakkoi

Standard: 冷たい Tsumetai

English: Cold

Being the northernmost prefecture and next door to Russia, it’s only natural that Hokkaido-ben have its own word for “cold.”

Example: このかき氷ってめっちゃしゃっこい!

Romaji; Kono kakigoori tte meccha shakkoi!

Standard: このかき氷ってめっちゃ冷たい!

Romaji: Kono kakigoori tte meccha tsumetai!

English: This shaved ice is super cold!

とうきび Toukibi

Standard: とうもろこし Toumorokoshi

English: corn

Hokkaido is famous for their sweet corn, and “toukibi” is a word you will hear a lot here as a result. A popular summer snack is corn on the cob with soy sauce and butter, and it’s made just like in the gif above! Japanese people tend to eat it using a toothpick, picking off kernel by kernel. So when I just rocked up, grabbed an ear and started going to town on it, they thought I was a barbarian hahaha.

Example: やっぱり、とうきびに醤油だね!

Romaji: Yappari, toukibi ni shouyu da ne!

Standard: やっぱり、とうもろこしに醤油だね!

Romaji: Yappri, toumorokoshi ni shouyu da ne!

English: Soy sauce really does go good with corn!

なまら Namara

Standard: とても totemo、結構 kekkou

English: very, super, rather

This word is like “menkoi,” in that it is famous throughout Japan for being Hokkaido-ben, but I rarely hear it in actual conversations. I hear people use it when they are surprised by something. “Namara oishii” has a nuance of “It’s (actually) very tasty.”

Example: 曇ってるけど、今日の天気はなまらいい。

Romaji: Kumotteru kedo, kyou no tenki ha namara ii.

Standard: 曇ってるけど、今日の天気はけっこういい。

Romaji: Kumotteru kedo, kyou no tenki ha kekkou ii.

English: It’s cloudy today, but it’s still pretty good weather.

なんぼ? Nanbo?

Standard: いくら? Ikura?

English: How much?

My friend asked me to go get a couple drinks from the convenience store. I came back with a bottle for her and for me and she asked, “Nanbo datta?” I thought that bo was maybe a counter for things, and desperately tried to figure out what we were supposed to be counting. Then she explained that, for whatever reason, “nanbo” means “how much (does something cost)?”

Example: そのお弁当はめっちゃ美味しそう!なんぼだった?

Romaji: Sono obentou ha meccha oishisou! Nanbo datta?

Standard: そのお弁当はめっちゃ美味しそう!いくらだった?

Romaji: Sono obentou ha meccha oishisou! Ikura datta?

English: That bento looks super good! How much was it?

ボケる Bokeru (for produce)

Standard: 腐る kusaru

English: go bad (produce)

In standard Japanese, “bokeru” means “to go senile” or “to develop dementia/Alzheimer's.” While I wouldn’t say it’s a slur bad enough that it would be bleeped out, it certainly isn’t a kind way to refer to aging.

So when my host mom told me, “I would give you some apples, but they’re all senile” I had no clue what she was going on about. But then she showed them to me, and they were all wrinkled like this:

Not exactly the most appetizing, but also not entirely rotten. I’m really not sure why Hokkaido-ben likens produce to senility, but if I had to guess, I’d say it’s because pretty much every single person with Alzheimer’s/dementia is wrinkled.

Example: このリンゴはボケてるから、パイでも作ろうか…

Romaji: Kono ringo ha boketeru kara, pai demo tsukurou ka...

Standard: このリンゴは腐りかけてるから、パイでも作ろうか…

Romaji: Kono ringo ha kusarikaketeru kara, pai demo tsukurou ka...

English: These apples are about to go bad, so I guess I’ll make a pie...

~べ ~be

Standard ~だろう、~でしょう darou, deshou

English: ..., right?

This is probably the most famous aspect of Hokkaido-ben. Japanese people get a real kick out of it when this white girl uses it haha. “~be” is a sentence-ending particle that functions about the same as “darou” or “deshou” in that it:

asserts the speaker’s confidence in the likelihood of something

asks for the listener’s confirmation

This sentence-final particle has its roots in the particle ~べし (~beshi) found in Classical Japanese, which had a similar purpose. Other forms of ~beshi survive in Modern Standard Japanese with the words べき (beki) and すべく (subeku).

Here are two examples, one for each function ~be fulfills.

Example 1: 君の飛行機はあと5分に出発するって?間に合わないべ!

Romaji: Kimi no hikouki ha ato 5 fun ni shuppatsu suru tte? Maniawanai be!

Standard: 君の飛行機はあと5分に出発するって?間に合わないでしょう!

Romaji: Kimi no hikouki ha ato 5 fun ni shuppatsu suru tte? Maniawanai deshou!

English: You said your plane takes off in 5 minutes? There’s no way you’ll make it!

Example 2: このサラダに白菜も入ってたべ?

Romaji: Kono sarada ni hakusai mo haitteta be?

Standard: このサラダに白菜も入ってたでしょう?

Romaji: Kono sarada ni hakusai mo haitteta deshou?

Standard: There was napa cabbage in this salad too, wasn’t there?

~れ ~re

Standard: ~なさい ~nasai

English: imperative command

I really don’t like giving grammar explanations because it’s been a long time since I’ve formally studied Japanese grammar and I’m scared of explaining something poorly or incorrectly. But an upper-elementary level Japanese learner should know that there are many different levels of imperatives in Japanese that vary in politeness. In order of rude to polite, we have:

Imperatives that end in an “e” sound or ろ, as in:

死ね!Shine! Die!

待て!Mate! Wait!

食べろ!Tabero! Eat!

Imperatives that end in tte, te, or de and are not followed by kudasai

死んで Shinde. Die.

待って Matte. Wait.

食べて Tabete. Tabete.

Imperatives that end in nasai. (These are most often used by parents/teachers to their children.)

死になさい Shininasai. Die.

待ちなさい Machinasai. Wait.

食べなさい Tabenasai. Eat.

Imperatives that end in tte, te, or de and have kudasai after them.

And then there’s super formal Japanese, but that’s a whole other kettle of fish.

Anyways. Back to the Hokkaido-ben. I went to a picnic here with a Japanese friend’s family, and her aunt gave me a plate of food and said, “Tabere!” I knew that this had to be an imperative, but I had never studied it before. It felt like it was the same as the rudest imperative, and I spent the whole rest of the picnic wondering what on earth I had done to have her family speak to me like that. Conventionally, they should have been using the -tte form or -nasai form with me.

After the party, I asked her, “Dude, what’s the ~re stuff for? Do they not like me?” I was close to tears I was so hurt and confused.

And that when she laughed and explained that the ~re is a facet of Hokkaido-ben, and it is the same in politeness and nuance as the ~nasai imperative used by parents and teachers to their children.

So I had spent several hours thinking that her family hated me, when really they were treating me like I was their own child!

Example: ちゃんと野菜を食べれ!

Romaji: Chanto yasai wo tabere!

Standard: ちゃんと野菜を食べなさい!

Romaji: Chanto yasai wo tabenasai!

English: Eat all of your vegetables properly.

The End!

This was a monster of a post. There are actually a few more words I wanted to introduce, but I had to cut it off at some point haha. I hope that you enjoyed this segment of Moderately Interesting Japanese. I plan to make more on the other dialects within Japanese, but they will take a considerable amount of time so they won’t be very often.

Thanks for reading!

#japanese language#japanese#japanese dialects#hokkaido#japanese linguistics#study japanese#learn japanese#japanese vocab#japanese vocabulary#nihongo#anime#manga#dragon ball#inuyasha#urusei yatsura#sailor moon#pokemon#pikachu#cowboy bebop#mononoke#moderately interesting Japanese#hokkaido-ben

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Theonymy: On the Names of fal’Cie

The gods of Fabula Nova Crystallis (FNC) are, as the title of the mythology would suggest, multifaceted. This post will be the first in a series that attempts to analyse them from a polytheistic, specifically, a fictional or otherworld reconstructionist perspective.

Names are essential to storytelling. In the Final Fantasy series of games especially, names are drawn from many different cultures and languages, even within the same title: Nomura Tetsuya, the series’ lead character designer for the last 22 years, and one of the creative leads behind the original Fabula Nova Crystallis project, drew from Okinawan (“Yuna”, night; “Tidus”, sun), Ainu (“Wakka”, water), and Arabic (“Lulu”, pearl) while creating the characters of the Final Fantasy X series. These names often subtly allude to the positions of the characters or their future arcs in the context of the story or its themes, and understanding their etymology can frequently be illuminating.

This doesn’t hold a candle, however, to the significance of the names of gods, which describe their relationship with the world itself, and have their origins in epithets used to describe them by their worshippers. For example, the chthonic jötunn Hel, whose name derives from the Proto-germanic *haljō, from the Proto-Indo-european *kol-, “to cover/hide”, as one covers a corpse in the soil of a grave; or the Irish psychopomp an Morrígan, whose name either translates to “Great Queen” or “Phantom Queen”, as befits a goddess who manifests to doomed warriors; or Nebt-het, the netjert of death, whose name translates to “Lady of the Temple Enclosure”, describing her role in ritual.

fal’Cie

Firstly, the term “god” itself should be addressed. Often applied in english-language literature across religious traditions to describe a wide array of entities, it often fails to capture the nuance that culturally specific terms have for these entities. For example, in norse tradition, the word “god” is typically applied to the Æsir and Vanir, but not their enemies (such as the Jötnar) despite the latter often being of equal power and cosmic significance to the former two; additionally, the word often fails to describe the nuance of the word “kami” in Shinto tradition.

This word, kami, in fact is the term often used to describe the higher deities in the original japanese scripts of the Fabula Nova Crystallis franchise (this term became “god” in the english, of course), particularly concerning the most supreme living being in the mythos: Bhunivelze, the Shining God (Kagayakeru Kami), for whom the terms for lesser spirits in the mythology were considered inadequate or degrading by his historical worshippers.

However, being apathetic (at best) to the Shining One myself, i will use this term for him anyway: fal’Cie, the name for a living, material god in the various worlds of the setting[1]. In the rest of this post, and in subsequent writing, i will use the collective and singular term “fal’Cie” to refer to inorganic spirits in Fabula Nova Crystallis that are themselves descended from inorganic spirits.

The term “fal’Cie” itself deserves analysis. In the original japanese scripts, the kana for this term is ファルシ, “faruShi”, which is very nearly a correct transliteration of the english-language word “fallacy” — whose definition is of course “a mistaken belief or error in reasoning.” This will become incredibly important later when i discuss the nature of mythology and cult within the setting, but for now let it simply be noted that it is important that the term used for spirits in this world is nearly synonymous with the concept of “misconception.”

The related term “l’Cie” provides another avenue for analysis of the theonym. l’Cie, written ルシ, ruShi, are (formerly) human servants or slaves of fal’Cie. The term, especially in the original scripts, is pronounced almost exactly the same as the italian “luci”, or “light”, and when romanised, is quite clearly just the french word “ciel“ or “sky” with the last consonant shifted forward. Both of these concepts allude to the origin and master of all living fal’Cie and, indeed, all souls and Matter in the FNC, in the most exalted Lord of Light, Bhunivelze.

The fa- prefix that forms the word fal’Cie is then theorised by FNC fans to have its origins in the Latin famulus “servant,” in line with the origin of the “fa” note in solfège (Do-Re-Mi-Fa-So-La-Ti) from the Latin hymn Ut queant laxis. This would, fittingly, give us an etymology for the term fal’Cie that comes to something along the lines of “Servant of Light/Heaven.” Personally, i’m not sure how much merit this association actually has, convenient though it is, so i’d like to propose an alternate theory.

There is only one obvious association that the fal- prefix could have in west european languages. It has already been covered, indirectly, but bears discussing again: the word “fallacy” derives ultimately from the Latin fallere, “to deceive,” and the fal- stem in descendant romance languages still retains this association with falseness (french and italian, used in the “l’Cie” part of the word, are, of course, romance languages, which makes an italic etymology for fa(l)- the most likely). This would give “fal’Cie” the etymology “Heavenly Deception” or “Deceiving Light,” both of which could help elucidate the beings’ true natures.

It should be further noted that words in japanese containing the syllable シ (shi), which is a homonym for 死 “death,” often become associated with death by association: for example, the japanese numeral 四 “four,” also pronounced shi, is historically considered inauspicious.

[1] i am aware that in the brand change from Final Fantasy Versus XIII to Final Fantasy XV, the term “fal’Cie” was replaced with “Astral” as a term specific to the world of Eos, but insofar as these entities still exist as the crystalline descendants of the Fell Trickster Lindzei and the Hallowed Tyrant Pulse, the theonym “fal’Cie” is still correct, and i will use it when describing these entities in the context of the wider setting. The word “Astral” itself shares connotations with the celestial etymology of the original term, which hints at the Astrals’ true nature, even after the rebranding.

Pulse

Stout fashioned earth,

that future might take root.

— Analect I, “The Vanished Gods”

The first theonym i would like to address is the most simple. Pulse, the Terrestrial Potentate, is a male fal’Cie who is credited with shaping the physical world. Concretely, this means he is the entity responsible for the creation of, well, nearly everything that can be seen, touched, or otherwise mundanely sensed in the mortal realm.

His symbol is ten bidirectional prongs or arrows emanating from a central eye, five upwards, five downwards. In Final Fantasy XIII we find its analogue in the many-pronged double-headed spears of the Gran Pulsian l’Cie Oerba Yun-Fang, which makes it doubly clear that this symbol is supposed to be phallic, and possibly a symbol of fertility or rulership, an association strengthened by the fact that the Etro-venerators of the Kingdom of Lucis and the otherworldly leisure house Serendipity depict Hallowed Pulse as the King on their playing card sets, and give him the title “the Mighty Potentate.”

The origin of the english word “pulse” is Latin pulsus, both words to describe a beat, throb, flow or stroke. This highlights the deep connection that the Hallowed Pulse has to the mortal world and all parts of nature that lie within, as the source of and indicator for the terrestrial realm’s strength and vitality.

The etymology of pulsus can reveal more, however: pellere, to push, drive, affect, compel, expel, propel, repel, dispel, impel, strike, banish, or conquer. This helps us see the significance of the ten arrows as a symbol of force, power, domination, and divine kingship, and solidifies the Divine Pulse’s associations with violent rulership or tyranny. Pulse is very much the archetypal patriarch, and the domineering attitude of his descendant fal’Cie towards the mortals they live alongside reinforces this.

Lindzei

Sage turned mind's eye inward,

seeking truth profound.

— ibid.

The third and youngest offspring of Light, the etymology of “Lindzei” is much less transparent than her elder sibling’s, but by examining the Heavenly Ruler’s iconography and associations, it is possible to determine some likely candidates.

Analect II, titled “Lindzei’s Nest,” from Final Fantasy XIII, gives us the following from the perspective of a Gran Pulsian demagogue:

And lo, the viper Lindzei bore fangs into the pristine soil of our Gran Pulse; despoiled the land and from it crafted a cocoon both ghastly and unclean.

Lies spilled forth from the serpent's tongue: 'Within this shell lies paradise.' Men heard these lies and were seduced and led away.

O cursed are the fools who trust a snake and turn their backs upon the bounty of Pulse's hallowed land! For those who dwell in that cocoon are not Men, but slaves of the demon Lindzei.

Ye who honor Pulse: rise unto the heavens, and cast down the viper's nest!

The serpent imagery here would seem oddly out of place if it weren’t for the universal symbol of Lindzei used by his descendant fal’Cie and the mortal societies she patronises. Lindzei’s symbol is that of a statuesque feminine figure with exaggerated hips, arms, and a headdress, whose stylised silhouette strongly resembles a uterus and ovaries. However, seen from another angle, this extremely stylised shape also resembles the hood of a cobra. It is fitting that a fal’Cie who is so associated with duplicity and tricks would be represented by such a multifaceted symbol.

This gives us a clue to the origin of the first part of Lindzei’s name. The germanic stem lind-, seen in the english word “lindworm” (dragon) and in many other germanic words for “snake”, has its origin in the Old norse linnormr, ultimately deriving from Proto-germanic *linþaz “flexible.” This is by far and away the likeliest candidate for the etymology of the Fell Lindzei, and strengthens the already existing trickster archetype or Satanic associations the gender-ambiguous (yet highly feminised) fal’Cie possesses.

The other associations of the word *linþaz are also worth discussing. The english word “lithe” descends from *linþaz, and the concept of flexibility or bendsomeness is itself highly relevant to the nature of this uranic fal’Cie. Lindzei is, above anything else, noted for his “dark cunning,” her skill with words, and, in the history of the Etroites, is effectively considered the midwife of the mortal races, who cultivated the very first human civilisations after their Goddess’ death. Given that societies patronised by Lindzei’s offspring (e.g. Cocoon, Milites) tend towards being extremely technologically and politically advanced, as well as lacking in superstition or fear towards the natural world, this idea has significant merit.

Which brings me to the Linden tree. Originating again from *linþaz, the Linden in germanic cultures has associations with femininity, divine protection and fertility, as well as truth-seeking, jurisprudence and political deliberation in general. All these associations are relevant to Lindzei, who above all his siblings is associated with the political life of humanity, and to whose followers is the true salvator and protector of the mortal peoples from nature or Pulse’s violent tyranny.

This leaves only the suffix -zei, pronounced “zeɪ” as in “say”. In fact, the word “say” — being of ancient germanic origin in *sagjaną, whose descendants are frequently pronounced as “z” (e.g. german sagen, dutch zeggen (past singular zei)) — is my personal best guess as to the actual etymology. Lindzei being so strongly associated with language and society, it seemed natural to me that this would be alluded to in her name.

Overall, this would give an etymology for the theonym that comes to something along the lines of “Speaking Serpent,” very fitting for a Lucifer-esque trickster figure.

In Analect VIII of Final Fantasy XIII, Lindzei is given an additional epithet “the Succubus,” which strengthens the Trickster/Satanic archetype associations, and yet further feminises the fal’Cie who is so demonised by devotees of Hallowed Pulse.

In Serendipity and on Eos, playing cards depict Lindzei as the Jack, with a caption describing him as “the Solemn Ruler,” who is “commanding from his throne on high.” This solidifies the uranic and political associations that the fal’Cie has.

Etro

Fool desired naught,

and soon was made one with it.

— Analect I, “The Vanished Gods”

For the Infernal Goddess, who is barely acknowledged by most mortal cultures in the setting, the problem of naming is particularly pertinent. To most peoples, She is simply Death, the embodiment of their mortality — but to those of Her children (for all mortals are born from Her broken corpse) who venerate Her, She is also known as “Her Providence”. This epithet is in fact the only name by which She is known specifically in the version of Eos depicted in the rebranded Final Fantasy XV, where the remnants of Her crystalline soul provided the Lucis Caelum[2] dynasty with its magic.

The epithet “Providence” of course alludes to Her gift (or curse) of prophecy, and associations with probability/entropy — misfortune, and prudent preparation to stave it off in particular.

Given that the Crystal of Lucis is referred to as the soul of the planet Eos itself, and yet is also termed the “Light of Providence” by the Astrals, it is possible that “Eos” is in fact itself another epithet for Her Providence Etro. Eos, originally greek ἠώς, means “Dawn” and is also the name used for the hellenic thea of the Dawn herself. This word ultimately derives from the Proto-Indo-european *h₂éwsōs of the same meaning.

It may seem counterintuitive for a Goddess of the Underworld to be referred to as the Dawn personified, but it is worth noting that She is also associated with entropy and disaster and yet is still called Her Providence. As the Lady of Chaos, She may bring the dawn if She so chooses by drawing the darkness back into the Unseen Realm, and in fact this is the role She plays as the Queen of Valhalla and by protecting the people of Eos from the Starscourge (which is a manifestation of the Unseen Chaos).

Like many death deities in our world, it is possible that Her true name is so rarely uttered because of this fal’Cie’s deathly nature, and how tied She is to destruction, chaos and entropy in general — it is not uncommon for such terrible spirits to often be referred to with euphemisms to avoid invoking either their wrath or their destructive natures. Surprisingly, one thing both Pulsian and Lindzeian cultures agree on is their fear of or even hatred for this entity.

Unlike Her sibling fal’Cie, She is entirely absent from the mortal realm and Her influence can only be felt through the chthonic Unseen Realm which awaits Her children between death and rebirth. Also unlike Fell Lindzei and Hallowed Pulse, Her Providence bore no fal’Cie of Her own, as She was granted no divine gifts in life.

The concept of the Unseen Realm will be revisited later in this series, but for now let it simply be noted that She is depicted as the Queen on playing cards created by Her devotees, and referred to on the writing below the illustration as “the Veiled Goddess.” Personally, i believe this epithet refers to mourning veils, as well as the veil between the Visible and Unseen Realms which is Death — i.e., “Veiled Goddess” is a euphemistic manner of describing Her nature as the Dead and Death Goddess.

The actual name of this fal’Cie (if indeed She can be considered a fal’Cie alongside Her kin) is not even alluded to until the very, very, very end of the post-game in Final Fantasy XIII, and outside its two direct sequels Her name is even then seldom referenced except euphemistically. There are many possible reasons for this, but that’s a topic for another post.

Children of Hallowed Pulse scour earth, searching substance for the Door. Those of Fell Lindzei harvest souls, combing ether for the same. So have I seen.

The Door, once shut, was locked away, with despair its secret key; sacrifice, the one hope of seeing it unsealed.

When the twilight of the gods at last descends upon this world, what emerges from the unseeable expanse beyond that Door will be but music, and that devoid of words: the lamentations of the Goddess Etro, as She sobs Her song of grief.

— Analect XIII, “Fabula Nova Crystallis”

Etro, written エトロ (Etoro) in kana, has an extremely ambiguous etymology, as is noted by several fans of the setting. i will list what i consider to be the likeliest possibilities here, and describe the reasoning behind each as best i can.

Firstly is the french être ”to be,” triply relevant due to the presence of french and other italic languages in the FNC’s theonymy already; the nature of the Veiled Goddess Etro as mother to all human-kind, midwife of all re-born human souls, and as She who endows mortals with the formless heart that delineates us from our fal’Cie cousins; and, lastly, due to a possible connection with the etymology of Her cosmic antithesis, the Shining God Bhunivelze, which will be covered in the next section.

Second is the italian tetro “gloomy”/”grim,” which has obvious connections to Veiled Etro’s chthonic nature as She resides in the perpetual twilight of the Unseen Realm of Death.

Third, the Breton etre “betwixt,” whose etymology is entirely distinct yet is geographically proximate to the previous french. Veiled Etro, powerless in the world of Her birth, was granted a power beyond any living fal’Cie in the Immortal Realm of Chaos, and used this power to grant this primordial force to Her mortal children in a perpetual cycle of death and rebirth, between one world and the other. Thus, the concept is relevant to Her nature.

Fourthly is the Proto-Indo-european *kʷetwóres “four,” an association that might be clearer when examining the numeral’s descendants, but which i am fond of as a potential etymology for Her Providence due to the association that the number has with death in japan, as discussed previously. The reconstructed *kʷetwóres becomes Latin quattuor, italian quattro, greek τετρα- (tetra-), Proto-balto-slavic *ketur-, and many others whose stems all resemble the name “Etro.”

Fifthly is the italian etra “heaven,” ultimately derived (via italian etere) from greek αἰθήρ (aether, transliterated into japanese kana as エーテル, “ēteru,” which is remarkably close to “Etoro”) which is a good way of describing the formless fluid nature of the Chaotic realm over which Her Providence Etro presides.

Last, but certainly not least, is the option that i personally find the likeliest: the Latin ceterus, or greek ἕτερος (heteros), both of which mean “other one,” both descended from the Proto-Indo-european suffix *-(e)teros — a suffix which means “one that is especially more than [prefix],” making fundamentally important word stems such as *ḱe- (here) or *sem- (one), into a general term for “that which is distinct from this.” This is incredibly important to understanding the Veiled Lady, who has largely been defined by being set apart from every other fal’Cie in Her lack of godliness, Her dominion over Chaos, Her cosmic opposition to the source of all living fal’Cie, and most notably, Her total absence in human culture or the majority of historical accounts concerning the world’s fal’Cie. Etro is the Great Other who is set apart from wider society, ostracised, scapegoated, and painted as a childish Fool or terrifying monster, regardless of cultural context or era.

Etro’s symbol is quite mysterious, as befits the Veiled Goddess. Similar to the etymology of Her name, there are many possible interpretations of Her sign.

The most obvious might be the image of a sprouting seed, which fits Her rebirth function and also matches the possible french etymology être.

The second is that of an eyeball cut in half longways, pointing downwards, which matches Her associations with prophecies and visions, as well as the world below. Etro’s Gate, the other of Her prominent symbols, which is the Door of Souls through which the dead and newly-reborn must pass to enter or exit the Unseen Realm, is also, notably, in the shape of an eye as seen from the front.

The silhouette also somewhat resembles an avian head viewed from the front, with the eyes near the base of the image, and this has immense importance to Her avian associations (the presence of (white — possibly swan) feathers is Her single most important omen/symbol after the Door of Souls). The softly-thinning curved prongs arguably resemble feathers themselves, or perhaps multiple sets of wings stretched upwards to the sky.

The fourth thing to note is the sphere of something fluid at the heart of whatever the image is depicting, which represents an organic flow of some kind, most likely the primordial Chaos that the Unseen Realm and the hearts of Her children are composed of. Within this dark fluid seems to be concealed some sort of staff or spike, which might represent a concealed blade or other weapon of some sort. Either way, this strengthens the already existing associations Her Providence has with concealment.

It might also possibly speak to the twin martial and spiritual functions, or, in DnD-esque Final Fantasy terms, physical and magical power — two things that are extremely relevant to Her Providence, who is so delighted by contests of violence. The fact that this dark fluid and the weapon concealed within are surrounded by the husk or wings/feathers of the symbol could either be an allusion to the Chaos that lies at the heart of every mortal (and Etro Herself), and the Unseen Chaos that Etro is charged with keeping at bay to preserve the Visible World.

[2] Note the connection to italian luci and french ciel here in the Latin Lucis Caelum, which are both referenced in the theonym “fal’Cie.”

Bhunivelze

Luminous lamented,

for creation spiraled unto doom.

— Analect I, “The Vanished Gods”

This supreme fal’Cie of light, “the god who rules all things,” and “holds the world in his palm” is in fact primarily referred to not by name, but simply as “God,” singular, monotheistic and absolute. He is also given many epithets related to light and the sun, such as “the Shining God,” or simply “Luminous.” All fal’Cie depicted in the setting, and thus, all Matter itself — everything that doesn’t stem from Chaos, to be clear — stem from this being’s great, near-absolute power as the self-made centre of all existence.

But his etymology is much less transparent than his realm. There are only a few narrow possibilities i have been able to find, and they are even then only tentative, so of the five entities discussed here i am most likely to revisit the Shining One at a later date.

“Bhuni-” may have an origin in the Latin bonus “good”/”right”, whose romance-language descendants often mutated the word into bun- stem words, all associated with correct morality. This has a credible link to Shining Bhunivelze’s associations with purification and correct action.

The second option i find more credible, myself: Proto-Indo-european *bʰuH- “to become”[3], which becomes Proto-germanic *beuną “to become” (from whence the english “be”/”been”), Kurdish bûn “to be,” Sanskrit भूमन् (bhū́man) “world,” भू (bhū́) “earth”/”matter”/”world,” and particularly भूमि (bhū́mi) “limit”/”extent”/”foundation”/”earth.” As Bhunivelze is the foundation of everything that can be seen in the material realm, and possesses absolute control over all visible Matter, his name being to do with the world itself, or the concept of limits/extents, or even matter/substance itself, would be extremely fitting.

The concept of Bhūmi is particularly relevant. The word represents the earth element in Hinduism, and is embodied in the devi of the same name who is analogous to “Mother Earth” and is also known as Prithvi; however, the term Bhūmi is used differently in Mahayana Buddhism. Within Mahayana-thought, the bhūmis are the ten[4] stages of attainment that must be passed in order to reach bodhi, or enlightenment. This concept is most certainly relevant to the self-declared most enlightened being in all creation.

“-velze” requires some more work. In katakana, his name is written ブーニベル (Būniberuze), which could help with finding more candidates.

Firstly, the dutch/Middle german vels(e) (plural velzen) “rock” — it is arguably a stretch, but i think it bears mentioning due to the fact that the Lord Bhunivelze does in fact have associations with stone/mineral — not just in that he is the god of all solid Matter (something that i will discuss later in the series), but that he is associated with crystalline structures in particular. In Final Fantasy XIII-2, we are given the following Oracle of Etro, which is the first time the Shining One is actually referred to by name:

In the physical world, it contains within its form endless chaos. By the will of the deities, it gives birth to all living things. I speak of crystal.

The eternal dream world of the crystal lies within the Unseen World. Even the gods long to find their way to that place. In all crystal, the heart that shines most brightly is called Bhunivelze.

— “Bhunivelze’s Sleep,” Yeul’s Confessions

With Proto-germanic *beuną this would give Bhunivelze an approximate etymology of “Stone Coming Into Being,” “Stone Appearing,” or “Growing Stone.”

Second is the Hindi वली (valī) “lord”/”saint”, which is even more of a stretch than vels to be honest, but is worth mentioning. This would give him an etymology akin to “Lord of the Universe.”

The last guess i have for this etymology is the english “verse,” from Latin versus, based instead on the original japanese pronunciation. The reason i think this is plausible is due to the Shining One’s connections to the Biblical God, whose words speak creation into being. This would, with Latin bonus or Proto-Indo-european *bʰuH-, give the Shining One an etymology something along the lines of “Good Verse” or “Verse Coming Into Being,” both of which are quite fitting.

We can go one step further from “verse,” however: If we take Proto-Indo-european *bʰuH-, and the original japanese pronunciation, we can form Bhu-niverse, which is to say, the english word “universe” (ultimately derived from Latin ūniversus, “turned into one”) — a lot more plausible given the numerous Sanskrit bhū́- stem words listed above meaning “entire world.” This is the likeliest etymology for Shining Bhunivelze, in my opinion, and gives us a final meaning of “the World Coming Into Being.” This concept is incredibly relevant to the nature of Bhunivelze and Matter in general in Fabula Nova Crystallis, and will be discussed at length later on.

[3] Here the possible connection to the speculated french etymology être for Etro, also “to be,” which would highlight their shared cosmic significance as the ultimate light and dark principles.

[4] The number ten is incredibly important to the Shining One, who bears ten wings in his full manifestation and whose Latin-alphabet name (not coincidentally, the Latin alphabet is sacred to him) is composed of ten characters.

Mwynn

Maker forged fal'Cie,

from fragments Maker's own.

— Analect I, “The Vanished Gods”

Barely referred to except by the hints of hints even in the most hidden parts of the Fabula Nova Crystallis video-games, the majority of our knowledge about this most ancient of deities comes from the 2011 Square Enix video describing the central mythology of the entire setting.

Mwyn is a Welsh word with a dual meaning, the more common of which is neglected by FNC fans, so i will cover the less common first.

Mwyn is an adjective meaning mild, tender or gentle, which alludes to the Deepest Mwynn’s role as Mother to all creation, and particularly in raising Her offspring Shining Bhunivelze (in the Mortal Realm) and Veiled Etro (in the Unseen Realm) and instructing them on their respective cosmic positions as the wellspring of all Matter and the shepherd of all Chaos. Unfortunately, the etymology of this word is unclear, but it might possibly originate from Proto-Indo-european *men- “to think.”

Mwyn also means “ore” or “mineral.” Similar to the hypothetical bhū́mi and vels etymology for the Shining One Bhunivelze, this is relevant to our Deepest Mother Mwynn as the ancestral crystal of every soul and heart and speck of Matter that exists, as far as can be known. The etymology for this word is not much better-attested, though likely ultimately descends from Proto-Celtic *mēnis, meaning the same thing, and ultimately from Proto-Indo-european *(s)mēy(H)- “to cut”/”to hew.” The concept of cutting/hewing crystal is central to the almost parthenogenesis-like method by which fal’Cie (and, indeed, the ancestral mortals born from the Veiled Goddess Etro’s blood) are created, so i ultimately find both definitions of mwyn to be relevant here.

Unfortunately, there is only one depiction of the Deepest Mother available for analysis, but unlike Her chthonic daughter, who is frequently depicted badly wounded, sleeping/comatose or dying, She is depicted with Her body and all Her limbs intact; and within a great tapering double helix, a great disc — likely the universe — lies beneath the soles of her feet. This symbol is ultimately the logo used for the Fabula Nova Crystallis setting as a whole, and it warms my heart to know this long-forgotten Goddess receives some recognition in this form.

In time the gods departed,

leaving all by their hands wrought.

Fal'Cie were as Man forsaken,

orphans of Maker absconded.

— Analect I, “The Vanished Gods”

i dedicate this etymological analysis to The Dead Goddesses: to my Veiled Infernal Queen, Etro, and to my Deepest Ancestral Mother, Mwynn. We stand guard over your legacies still.

#alterpagan#pop culture paganism#fabula nova crystallis#final fantasy paganism#final fantasy kin#ff paganism#ffxiii#ffxv#fft0#Lindzei#Etro#Bhunivelze#Mwynn#ffxiii kin#ffxv kin#fft0 kin#final fantasy xiii kin#final fantasy xv kin#final fantasy type 0 kin

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

That one that says there are barely any white people in anime is so funny. Like Lucky Star had a white character (Patty) back in the early 2000s and it's one of the earliest slice of life manga.

On the other hand we did not get a recurring Okinawan character until New Game and we did not get a full cast of Okinawans until Harukana Receive, and there are still two white characters in that main cast too.

The lack of Okinawan Characters in the genre as whole is something I find interesting considering Okinawa itself has been a backdrop for vacation episodes since the very first nichijou-kei anime Azumanga Daioh yet we only get a proper Okinawan character in 2016 but shes part of the side cast and it takes two more years from that for a show with an Okinawan cast that takes place in Okinawa to air?

Like I'm sure this says something about the nature of colonizers seeing places they have colonized as just places, disregarding the actual living people there but I need more time to articulate what I mean by that.

Also I'd like to add that there has not been a single Chinese or Korean character in any of these shows in spite of there being more people of Chinese and Korean descent in Japan, so that kinda proves that it's not about reflecting irl demographics but rather there being cultural reason for this, which since I'm not Japanese I can't really comment on in depth.

And let's not even start with the lack of Ainu representation aside from the cultural appropriation visible in shows like Dragon Maid, where the small dragon is wearing Ainu inspired clothing for no reason (from what I've read, I never watched dragon maid so maybe it's really woke about Ainu issues /s).

TL;DR: I can list off multiple white characters with ease, but can't do the same for other minorities in Japan, only taking into account a genre which has only existed for about 20 years.

#Long Post#Was originally gonna add it to the reblog but realized I was hyperfixating so created my own post#lilypad.txt

0 notes

Text

I'm not mixed? What am I?

I recently got into a conversation with a mixed Japanese woman about my identity as an Okinawan and Japanese individual and she told me that I’m not mixed. I fully understand that I don’t know what it feels like to be distinctively not Japanese looking and I also understand that under current politics, that Okinawa is viewed as a part of Japan. But what she said, hurt.

It made me realize that all my life, with multiple people, I have had to fight for my identity as an Okinawan.

When it suited the Japanese government, they cast my people as second class citizens and didn’t acknowledge them as Japanese and when it suited Japanese individuals, they also continued their discrimination, colorism, and racism both in Japan and abroad. Okinawans changed their last names to appear more Japanese. Okinawans lost a lot of their language and speakers because of Japan because it was different and not Japanese. A lot of Okinawan culture was viewed as wrong. My Japanese grandmother on my father’s side is descended from the Satsuma Clan and thought badly of Okinawans. I don’t know about you but to me this sounds as two distinctive cultures.

So, you may exclude me from your definition but I am mixed and I proudly will continue to perpetuate both of my cultures. The same goes for being Ainu and Japanese.

#submission#mixed#japanese#mixed japanese#indigenous#ainu#okinawan#uchinanchu#identity#クォーター#quarter

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

What fiction do I consume?

As a kid, the stories I liked best were international stories. My Aunt worked in Women’s studies in art history for Greco Roman Art at a major university, so she would give me mythology from various places around the world. My maternal grandmother would give me books about folktales of Russia, and occasionally find me things from different locales.

So, the countries and cultures I did get to read was pretty vast, though I admit to some weaknesses (not from a lack of asking, though).

Native American tribes: Iroquois, Apache, Cherokee, Blackfoot. A lot of Mid-West and NE, mainly folktales.

Anything I asked for South of the Border or Latin America I was denied. I’m still working on filling that gap. It’s my largest weakness. (And BTW, I voted a few times for them to show up and be studied in my HS class, but kids were lazy and didn’t want to read Garcia--they rather read something they read before.) I looked, too. Still dislike my school for skipping it and using black as the token PoC. (Not hating on black lit, more like, can’t you do all of the representation?)

Of course Europe. But covering Europe would be boring. PoC authors, of course Dumas (and yes, I know his controversy). And of course other diversity writers, but I got bored after being told this is the pinnacle of all literature over and over and people telling me over and over I was wrong for questioning it. (You know after reading worldwide lit, I had a clue...)

Rromani... had some folktales, but I’m not sure if I believe that collection.

African American Folktales. (Also West African folktales). And of course Egypt.

Central and Southern Africa I’m weaker on. (regionalities because of white people splitting tribes... and I read by tribe/culture, not by borders imposed by whites). Northern Africa I have fairly well, but I admit it could be better. I’m probably limiting it since I don’t generally like stories of colonization that much, and the US tends to import those and it really gets to me. I rather not have it in my subconscious.

I’ve read West Asian Literature. Mostly the older stuff. Some of the newer pieces as well. (The Blood of Flowers, for example--loved that one). Again, I have a severe aversion to colonization and trauma porn. (It’s from waaaaaayyy back before I came to the US, apparently. It runs back when I spoke only Korean.) I find myself skipping some of the modernist writings.

South Asian Lit I gobbled that up quite a bit. I have weaknesses in more modern lit. I did kinda ask. I have consumed Bollywood movies and try to keep up on those and try to make sure to consume at least South India as well. Afghanistan, Nepalese, etc. Again, I hate colonization lit. A lot. So I avoid it. I have watched enough BBC documentaries that I don’t need more.

I have a blank area in Central Asian Lit. I really, really want to read things from Kazakhstan, for example. And the Central Steppes. OMG, if you have books in English about the Ancient Central Steppes, yes, please. (Also I have a literary crush on the Silk Road, especially women traders. I’ll squeal for you. Fiction, non fiction. I want it.)

I’m working on Mongolia, but I have most of East Asia in hand. I’m working on the Nomadic tribes more and trying to understand some of the Chinese minorities (but it’s so hard to find their lit. And I looked. Korea, of course, Japan, and including the Ainu and Okinawans. And Taiwan--I want more stories from the tribe’s POV--the native ones. Both modern and ancient.

I’m weak on the Pacific Islanders. Filipinos, I have, but honestly, it’s a black pit up in my brain for stories that don’t sound like a white anthropologist collected them. South East Asia, I’m trying to crack it. Thailand, (I’m looking at the Ethnic minorities more--Dai, etc). Hmong, Laos, etc.

The places I don’t know, I want to know, genuinely. Not in the anthropology sense as much, as learning story conventions from around the world and validating those. Getting names of them. Learning their structures, and being able to understand them fully.

But I was told it’s impossible to learn the entire world of literature. But I want to at least have a go at it. BTW, book recs, I’ll take them. PLEASE. Especially non-colonialized literature without white people that is unashamed of using the literature conventions of the ethnicity is comes from. Translated or not, I’ll take them all.

0 notes