#she broke the fourth wall so hard she transcended generations

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

pinkie…. girl………….. what are you doing in there

#she broke the fourth wall so hard she transcended generations#nothing can stop pinkie#mlp#my little pony#mlp fim#my little pony friendship is magic#mlp g4#g4#mlp g5#g5#pinkie pie#mlp merch

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

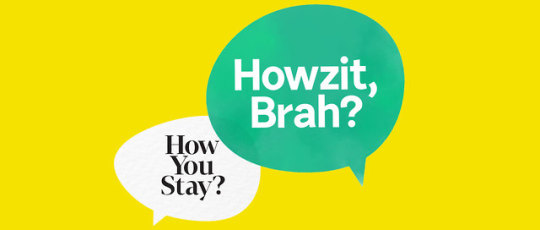

My Native Tongue

Published by Southwest The Magazine

I was raised on Hawaiian Pidgin English, a melting pot of a language that reflects the islands’ history, but it took me years to fully appreciate its importance, not just to local culture but my own identity.

I don’t know if there’s a sound that captures what it means to be from Hawaii quite like Hawaiian Pidgin English. Sure, there’s the voice of the beloved Israel Kamakawiwo‘ole, singing coolly over his ukulele about the white sandy beaches and the “colors of the rainbow, so pretty in the sky.” Or the rhythmic cadences of the ipu, a percussive gourd that soundtracked the hula lessons I attended at the local Y as a child. Or the soothing trance of waves tickling the shore of Ala Moana Beach Park at dusk while my siblings and I waited for Fourth of July fireworks. But nothing reflects Hawaii’s confluence of cultures, its medley of immigrants, quite like my father’s voice barking, “Eh! Das all hamajang!”

He was referring to my tile work, which, to be fair, was all hamajang: messed up, crooked, disorderly. What did he expect? I was a broke Syracuse University student, back home in Honolulu for the summer and working with my dad to fund an expensive semester abroad in London. I didn’t know how to tile a pool, a skill my father had perfected decades ago, during summers helping his own father run the family pool company. Down in the scorching pit of a concrete hole, I saw a different side of my father, whose mode of communicating tended to err on the side of silence. Here, leading a team of laborers from as far as Micronesia and as near as Waipahu, he gave directives, criticisms, and the occasional compliment in the staccato inflection of Hawaiian Pidgin.

“Cherry,” he’d drawl, the few times I managed to do something right. He’d stretch both ends of the word to sound closer to “chair-ray” and employ it when something looked impeccable. I’d savor that verbal pat on the back for hours. Other words were less descriptive. “Try pass the da kine,” he’d say, gesturing toward a pile of tools. Through the powers of clairvoyance—“da kine” is said to derive from “the kind,” a common Pidgin catchall for “whatchamacallit”—I mostly understood what he was asking for. When I returned with the wrong thing, he’d clarify, “No, the da kine da kine!”

Growing up in Honolulu, I didn’t learn Pidgin so much as absorb it; the language was as inherent to the texture of my upbringing as rubbah slippahs (flip-flops) and Spam. It originated on the sugarcane plantations that proliferated throughout Hawaii during the turn of the 20th century, leading to a burgeoning economy that brought immigrants from China, Japan, Portugal, Korea, and the Philippines despite less than ideal conditions. To communicate, plantation workers fused pieces of their native tongues with Hawaiian and English, creating a dialect to match an unprecedented convergence of cultures yearning to connect.

Though its origins are proudly blue collar, Pidgin in Hawaii is ubiquitous. Brash, sharp, and comically evocative, I heard it most frequently in the taunts hurled on my elementary schoolyard (“You so lolo,” meant someone was stupid), peppering the cadence of my aunty’s garage parties (“Brah, you stay all buss,” meant someone was drunk), and marinating the tongues at barbecues on the beach (“Ho! Get choke grindz” meant there was food, and lots of it). It’s the dialect favored by local comedians, who brandish its self-aware, anti-establishment humor as both identity and weapon: for locals only. It’s how we “talk story,” catching up over plate lunches in between the clinking of Heine-kens. It’s Standard American English dressed in an aloha shirt, trading its monocle for a pair of sunglasses. Construction workers, police officers, and bus drivers all speak it. So did my dentist. It’s not so much a reflection of local culture as the culture itself, as it is one of the fundamental things that makes Hawaii Hawaii.

To the foreign ear, it might sound like botched English, a gross simplification that ignores words like “are” and “is” (“You stay hungry?”), flips sentence structure on its head (“So cute da baby”), and employs colorful slang. “Broke da mouth,” for instance, is used when food is so “‘ono,” or delicious, that your mouth breaks, and “talk stink” means to engage in the odious art of bad-mouthing. But the Pidgin that locals speak today isn’t slang, broken English, or even technically Pidgin—defined by Merriam-Webster as “a simplified speech used for communication between people with different languages”—which might be the most Pidgin thing about Pidgin. Instead, generations of locals (some who speak exclusively in Pidgin) elevated what was once considered hamajang plantation talk into its very own form, replete with its own set of rules. Linguists define it as a creole, a separate language that was recognized as such by the Census Bureau in 2015.

Ididn’t grow up embracing Pidgin. After Pidgin-ing out on job sites, my father would code-switch back to “proper” English at home. Growing up, this fluidity felt central to the language, the almost subconscious ability to distinguish when it was appropriate to wield its power and when to stash it in your back pocket. Not understanding this difference had its consequences. My mother, who grew up on Kauai and moved to the “big city” of Honolulu to attend a private boarding school, recalls her high school history teacher ordering her to stand in a corner and stare at a wall. Her offense? Saying “da kine.”

This stigmatization traces back to those sugarcane plantations: Pidgin as broken English for the uneducated immigrant. The Hawaii State Board of Education has repeatedly attempted to ban Pidgin from the public school system, with former Gov. Ben Cayetano once declaring Pidgin “a tremendous handicap” for those “trying to get a job in the real world.” Growing up, I wore my Pidgin lightly, fearing that indulging in its subversion was a one-way ticket to nowhere, a way of limiting myself to the bottom of that concrete pit.

In the ’90s, a wave of writers and activists fought to combat this perception, sparking something of a Pidgin Renaissance. Through poetry, novels, and essays, writers like Lois-Ann Yamanaka, Lee Cataluna, and Darrell H.Y. Lum positioned the once dismissed dialect as literature. Emerging out of that shift stomped Pidgin theater, Pidgin dictionaries, and a Pidgin Bible, dubbed “Da Jesus Book.” “Talking li’ dat” (“like that”) even managed to penetrate the most resistant institution: academia. At Syracuse University, to my shock, I studied Yamanaka’s seminal novel Blu’s Hanging, which mines the Pidgin of its protagonist to spotlight the underbelly of working class Hawaii. In 2002, the University of Hawaii at Manoa established The Charlene Junko Sato Center for Pidgin, Creole, and Dialect Studies, dedicated to conducting research on “stigmatized dialects.”

A leading voice in the movement is Lee Tonouchi, who’s often referred to as “Da Pidgin Guerilla.” In the late ’90s, as a student at the University of Hawaii, Tonouchi had an epiphany while reading a poem by Eric Chock, who co-founded Bamboo Ridge Press, the leading publisher of Pidgin-centric writing. Titled “Tutu on the Curb”—“tutu” being Hawaiian for grandparent—Chock’s poem is expressive and comical: “She squint and wiggle her nose / at the heat / And the thick stink fumes / The bus driver just futted all over her.”

“I remembah being blown away by da Pidgin,” Tonouchi, who writes and speaks exclusively in Pidgin, says by email. “I wuz all like, ‘Ho! Get guys writing in Pidgin. And we studying ’em in college. Das means you gotta be smart for study Pidgin!’”

Tonouchi started flirting with his native language scholastically, first in his creative writing class, which got him thinking: If I can do my creative stuff in Pidgin, how come I no can do my critical stuff in Pidgin too? Over time, he started writing his 30-page research papers and his entire master’s thesis in Pidgin, “until eventually I just wrote everyting in Pidgin.” Part of the decision was practical. As a kid growing up on Oahu, he felt perplexed by the books he read. People no talk li’ dat, he thought. “Writing how people sounded seemed more real to me,” he says.

Since graduating, Tonouchi has dedicated his life to establishing Pidgin as its own intellectually rigorous and poetically descriptive language. He’s published multiple books of Pidgin poetry and essays, written a play in Pidgin, and co-founded Hybolics, a literary Pidgin magazine that’s short for hyperbolic, used when someone is behaving like a snooty intellectual: “Why you acting all hybolic for?” Perhaps most groundbreaking was an English class called “Pidgin Literature” that he taught at Hawaii Pacific University in 2005. It was regarded as the first of its kind: a college course fully dedicated to fiction and poetry in Pidgin. Yes, brah. He even lectured in Pidgin.

Over the years, Tonouchi has noticed a decline in Pidgin, particularly among the young. “When I visit classrooms as one guest talker, I see that we kinda losing da connection. Simple kine Pidgin vocabularies da kids dunno,” he says. “I tink Pidgin might be coming one endangered language.”

There was a period in my life, after I moved away for college, when I scrubbed Pidgin from my lips, my tongue colonized. “You talk so haole,” my mom would say half-jokingly, employing the Hawaiian word for “Caucasian.” I knew my tongue should loosen, should adapt to the inflection of my aunties and uncles, to the comforts of poke and Mom’s home-cooked shoyu chicken. I was home for the holidays, surrounded by friends and family, but instead my tongue stiffened, intent on proving that I had transcended the confines of the tiny island I called home. I was acting all hybolic.

It took me years to realize that shunning Pidgin meant shunning where I was from, the food I ate, the beaches I roamed, the people I loved. Today, it’s hard for me to fathom a Hawaii without Pidgin. Particularly in rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods, how else would locals, with a single sentence, signal their localness to one another?

On a recent visit home, I went to the beach. Oahu’s North Shore is a disorienting mix of sunburnt tourists and the very local; having lived in New York for more than seven years by that point, I imagined I looked like a cross between the two. As I sat in front of the crashing waves, a tanned surfer with sun-bleached hair approached me apprehensively to ask for a bottle opener. “Try wait,” I said, rummaging through my beach bag.

It was barely perceptible, but his face flashed with the comfort of recognition: He was talking to a kama‘aina, a local. After I handed over the bottle opener on my key ring, he had one more question. “You like one beer?”

0 notes